5 minute read

FLASHMAN

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS © DOUGLAS FRIEDMAN

Advertisement

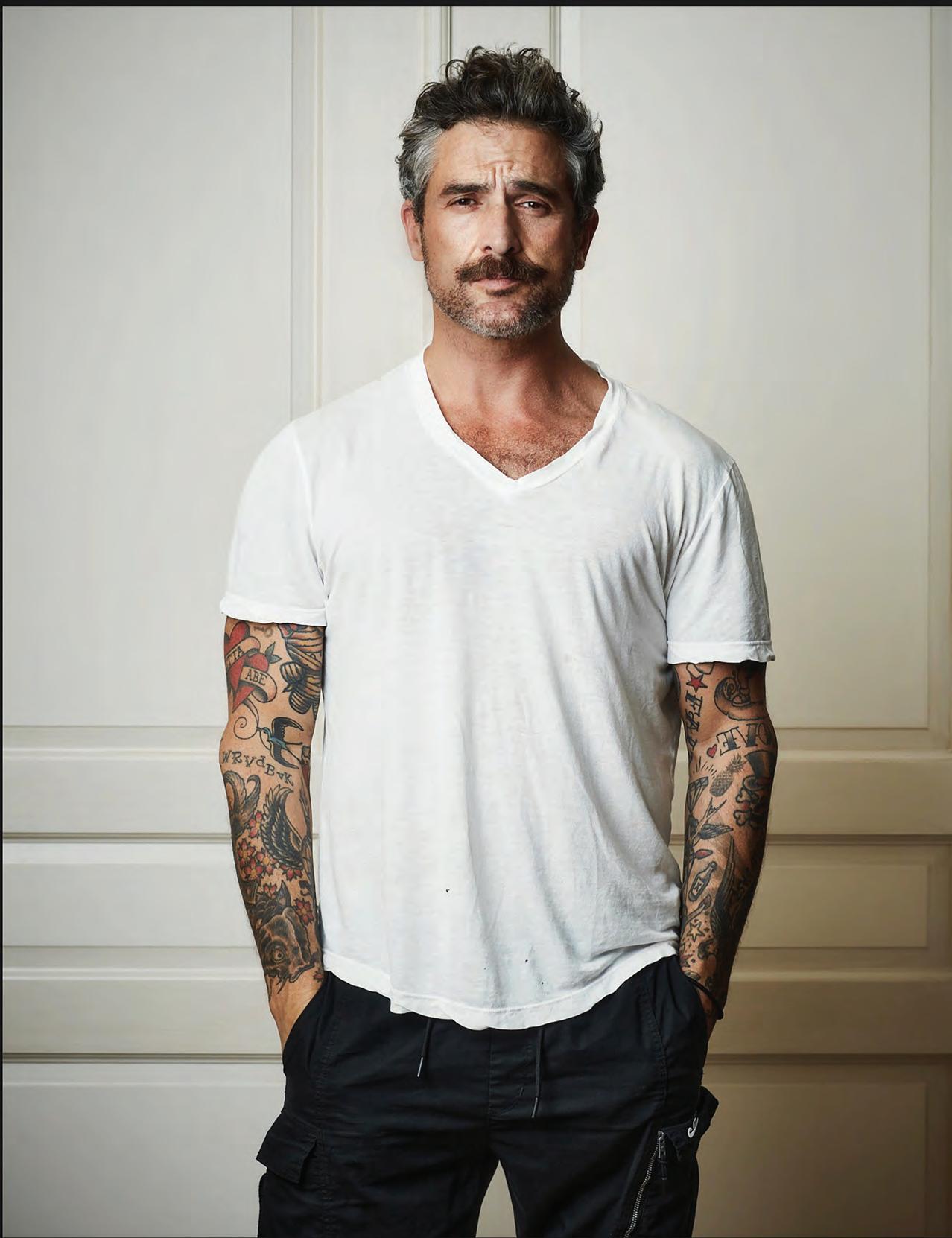

SELF-PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN Left: Douglas Friedman’s self-portrait. Above right: an untitled, dream-like interiors shot from the HyperOpia series. Photographs throughout are also from the HyperOpia series.

The debonair Douglas Friedman, interiors photographer to the stars, talks to Peter Davis about his fall show in New York

Easily recognizable—with heavily tattooed arms and his signature ’70s mustache—Douglas Friedman has quickly become the It Boy of the design world. An Instagram star with a fanatical A-list following of people such as his close pal Martha

Stewart, the interiors and architecture photographer has become famous in his own right, fitting right in with the celebrities he shoots at home for magazines such as Architectural Digest and Elle

Decor. Oozing style and boyish charm, Friedman is also a social force, gliding between Hollywood movie premieres and society soirees on the Upper

East Side, his high-profile friendships making him an easy choice for bold-faced names to open their doors and let him shoot their homes, among them Cher, Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis, Naomi

Watts, and Justin Theroux. “I’ve known Douglas for well over a decade,” says interior designer Ken

Fulk. “He’s fiercely funny, with a childlike sense of wonder about the world. It’s quite contagious when you’re in his presence. He’s an immense talent and a true artist.”

But successful interiors shoots aren’t all about a charming photographer and perfect lighting.

“There is a lot to navigate in a home shoot,”

Friedman explains, who splits his time between

New York, LA, Brookhaven, where he owns a home, and his main residence in Marfa, Texas.

“The most challenging is not freaking out the

homeowner when they see the amount of furniture that gets moved around.” So how does Friedman get his subjects to relax as their house is turned upside down? “I get them really drunk,” he cracks, adding: “That’s my secret sauce.”

When not capturing Kylie Jenner in her candy-colored Hidden Hills home for the cover of AD or posting to his Instagram account images of juicy steak dinners or ominous Marfa landscapes, Friedman is committed to exploring more personal, less commercial work. His latest and most creative project is HyperOpia, a limited edition photography series of 15 pieces that is decidedly not editorial. HyperOpia—which is a medical term for farsightedness—came to be when Friedman’s pal, the Los Angeles–based designer Ben Soleimani, asked him if he would mount a show for his new, massive flagship showroom on Madison Avenue. One catch: Friedman had to create the new body of work in under two months. “I had no idea what it was going to be,” he recalls. “I just knew it had to be a show about how to see something familiar in a fresh way. I didn’t want to show beautiful interiors or landscapes. That would be too obvious and, well, boring.”

Friedman began to experiment with the concept of focus. When he shoots an interior for a magazine, he strives for as sharp a focus as possible, so “you can see a crumb on a kitchen counter.” For HyperOpia, he wanted to show interiors in a way that was more thoughtful and would engage the viewer for longer. After a couple of weeks spent poring over his own body of work, he devised a formula he describes as a “very specific recipe for manipulating images in postproduction.” He looked at hundreds of photographs in his archives for interior shots that were as “beautiful in focus as they would be out of focus.” The manipulated images were then printed using largescale industrial printing machines at a facility in east Los Angeles. “It wasn’t a sterile environment, like a fine art printing press,” he explains. “It was a brutal, aggressive way to print that produced beautiful results. The paper was soft and matte and we let the inks bleed. I wanted these to look like paintings when you’re up close. Then when you step away, you can see a room come into focus. That’s when the magic happens.”

The large-scale (40x50-inch and 60x70-inch) pieces in HyperOpia resemble lush, colorful abstract paintings, recalling the seminal work of German artist Gerhard Richter and his “blurred” photo-paintings, as well as conceptual photographer Uta Barth’s plays on perception and vision. The dream-like HyperOpia photographs feel both oddly familiar and yet like an optical illusion of a non-place. “Douglas is always pushing the boundaries,” says Martha Stewart. “These recent photographs arouse the senses while bringing an intensely beautiful implication of a room into a framed photo. The out-of-focus images cause speculation and question the viewer’s understanding of space and color.” Soleimani was so taken with the 15 pieces in the exhibit that he asked

Friedman to mount another show, which is currently in the works. “Douglas’s talent is limitless” Soleimani says. “What he created was something I could never have imagined—so rich in mood and tone and very cinematic.”

A native New Yorker, Friedman graduated from Occidental College in Los Angeles and started his career as an assistant to director David Fincher, working on films such as Fight Club and The Game. But after a few years on movie sets, “I realized I was not going to be a film director,” he confesses. Friedman packed a backpack and a camera, left Hollywood, and bought a one-way ticket to Indonesia, shooting everything he saw, from the sherpas at the foot of Mount Everest to sharks 100 feet below the Sulawesi Sea. He returned to New York in the late ’90s, just before his 30th birthday. “I had no idea what I would be when I grew up,” he admits. “But I did need a job. I needed to pay the rent.” A friend got him a parttime gig as a photographer’s assistant and soon he was shooting editorials for Glenda Bailey at Harper’s Bazaar.

Since then, Douglas has barely put his camera down. “Once I experienced photography as a paying job, I knew it was for me—I just didn’t know how hard it would be,” he laughs. “I’m actually glad I didn’t know how hard it would be, because I would have done something else.”