In Memoriam JOHN B. RIDPATH

1936–2021

1936–2021

John B. Ridpath—intellectual historian and longtime member of the Ayn Rand Institute’s board of directors—died on March 23, 2021, in Kingsville, Ontario, Canada. In this commemorative publication, we pay tribute to his life by sharing remembrances from those who knew him, excerpts from his writings and talks, and facts about his life and his efforts to advance Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism.

Dr. Ridpath was an associate professor of economics and social science at Toronto’s York University from 1975 until his retirement in 2001. During his career he received several awards for excellence in teaching, related primarily to his large-group introductory economics course and his course on ideas and Western civilization.

He was an active debater, appearing at many universities to debate other scholars on the question of capitalism versus socialism, communism, the mixed economy and welfare statism. (A highlight was “Debate 1984: Capitalism or Socialism: Which Is the Moral System?,” staged in Toronto and available for viewing on YouTube.) He also spoke frequently to university audiences on the topics of individual rights, capitalism and the history of economic ideas.

Following the Ayn Rand Institute’s founding in 1985, Dr. Ridpath served on its board of advisors (1985–93) and board of directors (1993–2011). He was also a popular lecturer at Objectivist conferences, usually examining the causal importance of ideas in history and paying tribute to America’s Founding Fathers.

John Bruce Ridpath was born on May 19, 1936, in Toronto. He received his high school diploma there from Upper Canada College, and then went on to earn degrees in engineering and business administration from the University of Toronto.

Reading Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged ignited a lifelong interest in ideas and their historical impact. He entered graduate school at the University of Virginia in economics and secured a position as lecturer in economics and social science at York University in 1967. Upon receipt of his PhD in 1975, he became an associate professor and served as such until his retirement in 2001.

2 In Memoriam : : John

Ayn Rand Institute

B . Ridpath

Dr. Ridpath was an enthusiastic and reliable supporter of the Ayn Rand Institute and its affiliated programs designed to spread Objectivism.

Dr. Ridpath knew Ayn Rand personally and accompanied her to talks at the Ford Hall Forum in Boston. Two of his articles, “Nietzsche and Individualism” and “The Philosophical Origins of Antitrust,” appeared in the Objectivist Forum

He married Virginia “Ginny” Grant in 1962, and in their twenty-two years of marriage they had three children: Jefferson, John and Larkin.

Dr. Ridpath was an enthusiastic and reliable supporter of the Ayn Rand Institute and its affiliated programs designed to spread Objectivism. Besides his roles on the board of advisers and board of directors, he was instrumental in securing donations exceeding $500,000 for the John B. Ridpath Fund for New Intellectuals, formed in 2014 to support ARI’s Objectivist Academic Center, summer internship program, OCON summer conference scholarship fund, and Junior Fellows Program. Following his death, ARI announced the John Ridpath Memorial Fund for the purpose of supplying scholarships to conferences on Rand’s ideas and to the Objectivist Academic Center, where students receive an in-depth education from experts on the philosophy of Objectivism.

In the mid-1990s, Dr. Ridpath became an early adopter of planned giving as a means of supporting ARI financially, and he was a special guest (along with Mary Ann Sures) at a 2003 event supporting Atlantis Legacy, ARI’s planned giving program. His role in the Institute’s acquisition of sculptor Sandra Shaw’s portrait bust of Ayn Rand is highlighted in a later section.

3 In Memoriam : :

Ayn Rand Institute

John B . Ridpath

SELECTIONS FROM DR. RIDPATH’S WRITING AND ORATORY

We have assembled some lightly edited highlights of John Ridpath’s writing and oratory.

The first excerpt is from remarks delivered on October 14, 2011, at the unveiling of sculptor Sandra Shaw’s portrait bust of Ayn Rand, commissioned by Dr. Ridpath and Mary Ann Sures and donated to the Ayn Rand Institute (with support from Doug Arends) for installation in the lobby of ARI’s headquarters.

Iwould like, for this occasion, to comment on what this work means to me and what it means to ARI to have it here.

First, this is Ayn Rand’s physical countenance—there are no distracting physical surprises or distractions at all. And secondly, this is Ayn Rand in a profound moment of intense focus, and deep emotional reaction to what she is seeing before her. My view is that what she is seeing, embodied as John Galt, is man at his vibrant best: focused; evaluating; acting with rational conviction and passion; achieving; and proud of having achieved.

For all this, Ayn Rand, as presented in this work, is experiencing full, secular reverence. And finally, given all she knew, and what I knew of her, I see here in this bust before me Ayn Rand’s reverence for herself.

All this, present in this work and thus made objective for us to encounter, in physical form, is what this work’s value is to me and my life. It says YES, to life and YES, to my own life, every day, from its pedestal in my living room.

4 In Memoriam : : John B . Ridpath Ayn Rand Institute

In 2011, donations from John Ridpath and Mary Ann Sures helped fund a special casting of the portrait bust of Ayn Rand, sculpted by Sandra Shaw, which graces the lobby of ARI’s headquarters in Santa Ana, California. (Image courtesy Sandra Shaw)

What, therefore, can this bust mean to all of you working here at the Ayn Rand Institute?

It can act as your “Statue of Liberty,” welcoming you to this harbor of rationality, purpose, industry and importance where you work. It can both fuel you for the journey, and give you an image of where we all seek to go—to a world fully fit for human life. This can serve, within these offices, as your Wyatt’s Torch, standing as the living flame of your work, out of which all that is good will eventually arise. From Ayn’s hand to us, the torch has been passed, for us to carry forward.

This excerpt is taken from “The Philosophical Origins of Antitrust,” published in the June 1980 issue of the Objectivist Forum .

The world of perfect competition is described . . . as having the following characteristics. Everyone is omniscient concerning all economic opportunities, all factors of production are infinitely mobile and infinitely divisible, every market contains an infinite number of buyers and sellers, no one has any “sentimental” (i.e., non-pecuniary) interest in anyone else, all the products of competing firms are identical, and no innovation occurs in any field.

Under these conditions, . . . no business would be able to earn more than would be required to cover its operating costs plus an interest return on its capital investment. No part of “society’s income” would be withdrawn as “pure” profit. . . .

The implicit premise of the perfect competition theory is that businessmen are to be conceived not as productive creators, but as cogs facelessly involved in a process that spews out undifferentiated goods to impassive throngs—that businessmen can exist and function as selfless automatons with nothing to gain and no power to affect the process. It is the improper focus on distribution and consumption that made possible this notion of a “perfectly competitive” businessman. . . .

The altruist ideal of unrewarded service to others motivated the acceptance of the perfect competition model and its use as a standard for antitrust. The root reason why lawyers, economists, politicians and businessmen accepted this model and hold it as a virtually unchallengeable standard, is that the conduct it depicts is perfect according to the altruist morality. The model appeals to altruists because it describes a world in which everyone is acting to best serve the interest of the consuming public—a world in which goods are automatically distributed in such a manner that no one receives any selfish gain “at the expense of” others, and in which everyone participates in a process that gives the most satisfaction equally to all. . . .

This is the moral meaning of the standard used by modern antitrust. Businessmen are being persecuted for not being sufficiently identityless, passive, altruistic servants of consumers.

5 In Memoriam : : John B . Ridpath Ayn Rand Institute

This passage is excerpted from “Nietzsche and Individualism,” published in the February and April 1986 issues of the Objectivist Forum

Astudy of Nietzsche’s basic philosophy—his metaphysics and epistemology— clearly shows that there is nothing in his fundamental views that is in any way compatible with a social philosophy of individualism. If an individualist society is based metaphysically on the idea of rational man, living in an ordered and causal world, exercising his mind’s free will to choose and seek rational values; by contrast, what we have in Nietzsche is a wild, unpredictable willdriven reality, inhabited by a determined, fatalistic by-product and plaything of cosmic forces—man— who follows his urges and lives the life destiny offers him. Nietzsche, in essence, is denying: the existence of individual entities; the possibility of free will; the efficacy of reason. He is, on all fundamental grounds, an enemy not an ally of individualism.

Individualism is the advocacy of man as an end in himself, of individual rights, of the state limited to the protection of rights. Nietzsche is putting forth the most extreme denial of individualism possible— racist, elitist tyranny—and Nietzsche does not for a moment back away from admitting this.

6 In Memoriam : : John B

Ayn Rand Institute

. Ridpath

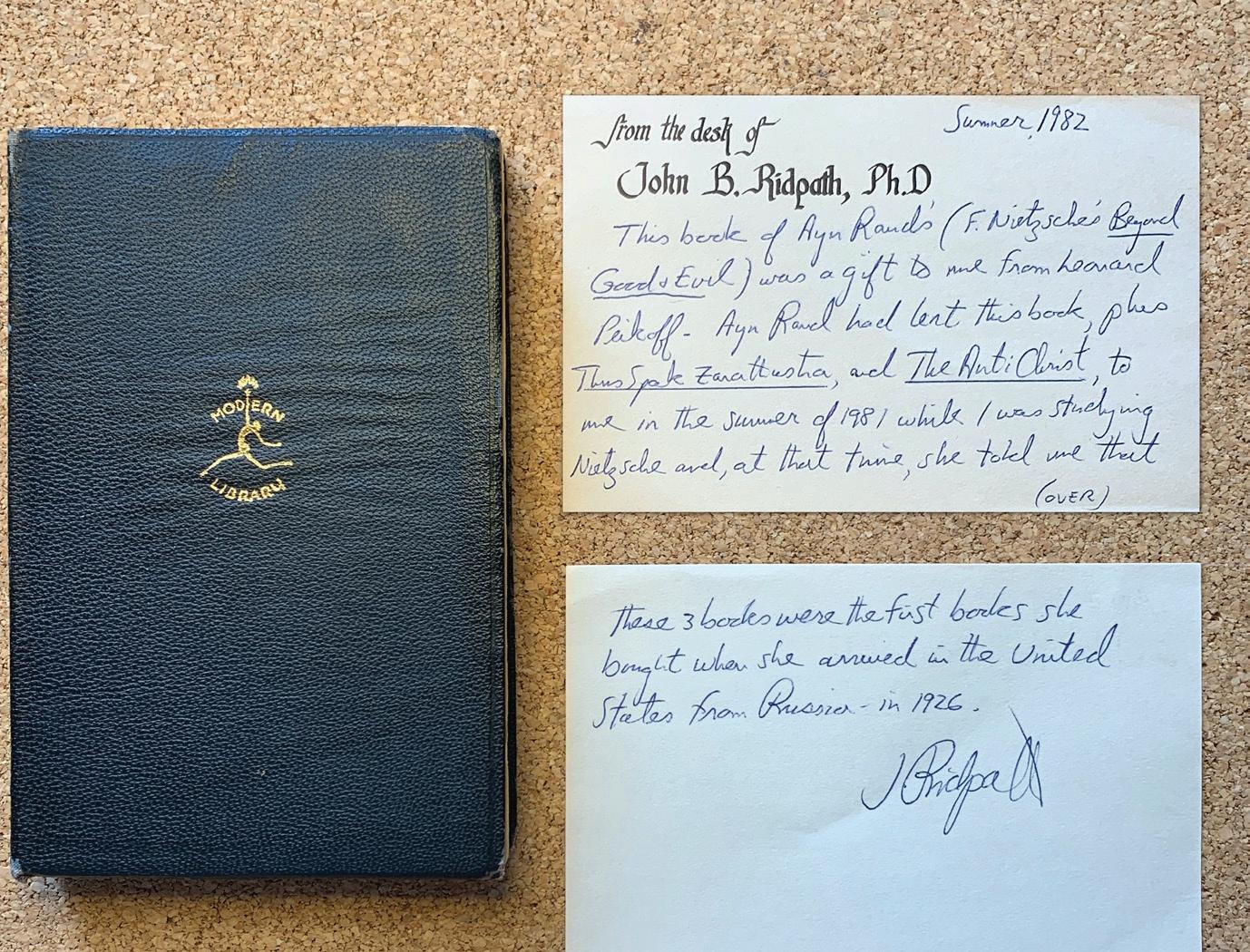

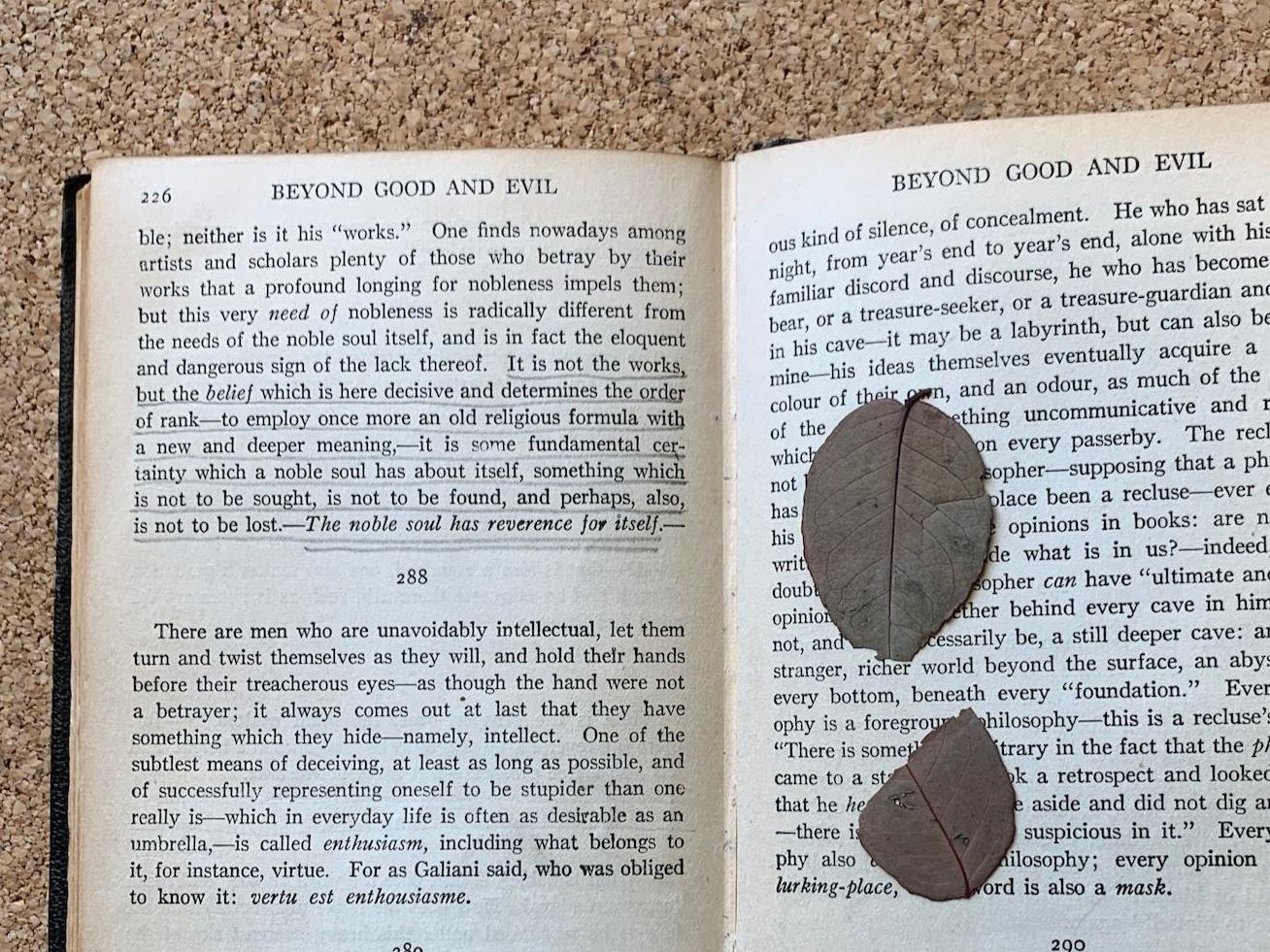

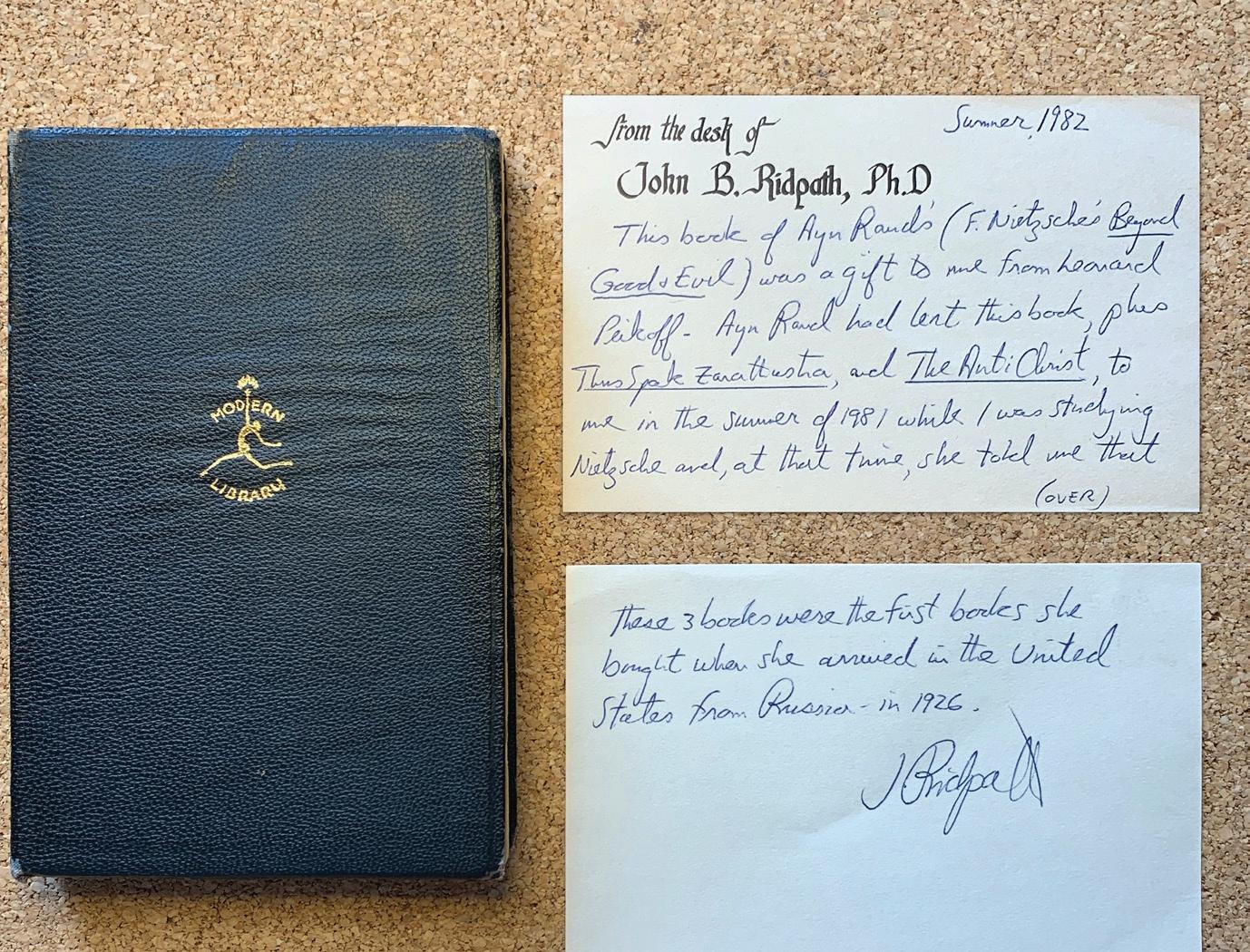

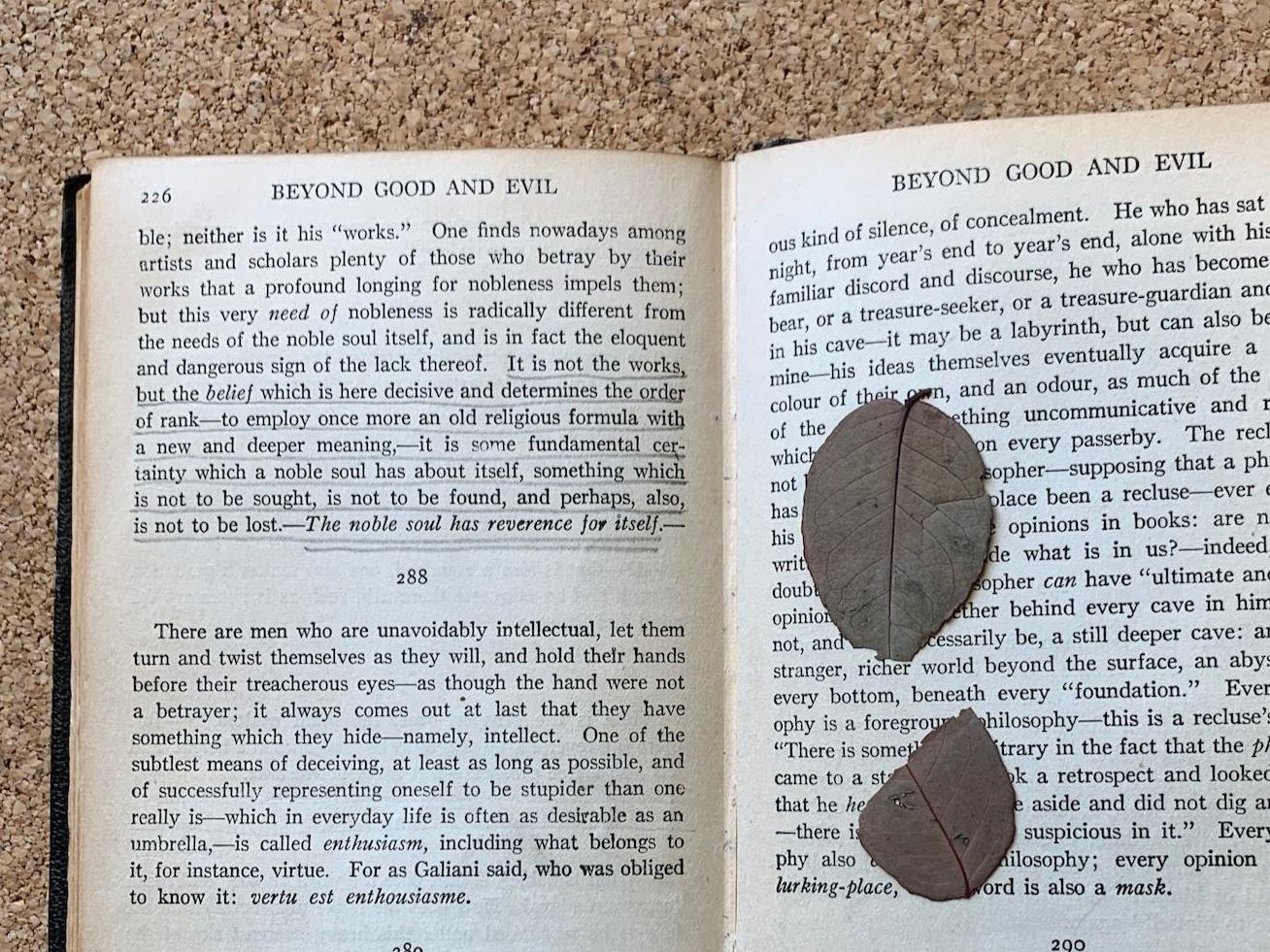

In her personal copy of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil, Ayn Rand underlined an important passage whose significance she explained in her 1968 introduction to the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of The Fountainhead. (Image courtesy Jefferson Ridpath)

Ayn Rand’s personal copy of Beyond Good and Evil by Friedrich Nietzsche, purchased shortly after her 1926 emigration to America, was lent to John Ridpath during Rand’s lifetime and gifted to him by her estate after her death. (Image courtesy Jefferson Ridpath)

Only in Kant’s wake could Nietzsche, with his profoundly anti-Western philosophy— his will-permeated Heraclitean reality; his emotivism; his mysticism; his glorification of instincts and power; his dream of a caste society—be given a serious hearing in twentieth-century culture.

Dr. Ridpath contributed a chapter called “Russian Revolutionary Ideology and We the Living ” to the book edited by Robert Mayhew, Essays on Ayn Rand’s “We the Living,” from which this passage is taken.

By 1959, Ayn Rand had repudiated every one of the components of the Russian revolutionaries’ guiding vision—a vision that is both false, and mystical, and as such is guaranteed to produce the tyranny, misery, and destruction that this vision has spawned across the twentieth-century world.

Specifically, she had demonstrated that (1) the determinate force in history, being man’s doing and not history’s, is under man’s control; (2) that men can, and must, choose to think and then control their own future; (3) that contradictions exist only in human minds suffering from error or irrationality, and explain nothing about the necessary unfolding of reality; (4) that individually or governmentally initiated violence is man’s primary social evil; (5) that men, not history, must achieve truly human lives, on their own; (6) metaphysically, only individuals (not collectives) exist and are ends in themselves, not history’s means to collective ends; and finally, (7) Irina is right—individual life is sacred, and is never to be sacrificed to any allegedly higher collective goal.

In 1992, at an Objectivist summer conference in Williamsburg, Virginia, John Ridpath delivered perhaps his most memorable speech. Inspired by the conference’s location, he focused on the part played by Virginians in the run-up to the American Revolution. In this passage, he describes Patrick Henry’s famous address to the Second Virginia Convention at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond. What follows is a transcript of Dr. Ridpath’s description of that historic, patriotic event. (Of course, the transcript necessarily falls short of fully recreating that 1992 speech—without audio, one cannot experience the emotion in his voice as he describes Patrick Henry’s oration, and without video, one cannot experience his dramatic enactment of the speech’s climax.)

What he did on that day was throw down the gauntlet of war. He rose, it was written later, “with an unearthly fire burning in his eyes,” to deliver a sermon on what in his words were the “illusions of hope.” He saw

7 In Memoriam : : John B

Ayn Rand Institute

. Ridpath

all those around him indulging in illusions. He wanted to bring everyone there to what he referred to as the bar of judgment—to present each one of them with “a question of awful moment”—and that question was, “Am I personally going to evade the fact that we are at war, or am I going to acknowledge the fact that we are at war, and act accordingly?”

What he said was that while he did not wish to question the abilities and the patriotism of his associates, he had to confront the assembly with this question: freedom or slavery? We must not be said to act out of fear of giving offense to others. He must not commit the treason to his country which he believed it would be if he did not tell them his assessment of the situation. He said that you have to face the truth: that the British cannot be misunderstood by superficial civility. He said: We are at war. He said, you must not be deceived by “the insidious smile” by which the British receive our petitions. He warned the House: “Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed by a kiss.” Rather, he said, see what lies before you. The implements of war, he said, are here, “sent over to bind and rivet upon us those chains which the British ministries have been so long forging.” We have done all we can, and there is no longer any room for hope. “If we wish to be free, we must fight.”

Now, the speech to this point was delivered in what was referred to as the “calm dignity of Cato of Utica.” But now, with the climax of his argument approaching, spectators commented on “the unearthly fire burning in his eyes,” “the tendons in his neck standing out white and rigid, like whipcords.” He carried on to tell them that the colonies are strong enough to win. The battle, he said, “is not to the strong alone. It is to the vigilant, the active, the brave.” Our chains are forged, he said; there is no longer any choice.

8 In Memoriam : : John B . Ridpath Ayn Rand Institute

John Ridpath at an Objectivist conference in 1987. (Image courtesy Godfrey Joseph)

And then came the immortal words: “Gentlemen may cry Peace! Peace! but there is no peace. The war is actually begun. Why stand we here idle?” And then he took the pose of a slave. And he crossed his hands and he bowed down, and he said: “Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?” And then he leaned forward, and it was reported that he said with a hiss coming out of his mouth: “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me Liberty”—and he threw his hands up in the air, and he paused in the silence in the House, and then he dropped a hand—“or give me Death!”—and he plunged his other hand into his breast.

And that was the end of his speech. What happened was that the whole House was stunned. It was reported that no one could look at his neighbor. Everyone had been driven by Patrick Henry into one’s own conscience, and what am I going to do? And it is reported that finally, a young enlisted soldier who was listening from outside through the east window of the church, sighed—everybody could hear his sigh—and then he said: “Let me be buried at this spot.”

In Memoriam : : John

The Philosophical Origins of Marxism, by John Ridpath, a four-lesson course examining Marxism as a secular version of the Judeo-Christian redemption saga, can be accessed at aynrand.org/ridpathmarxism

B . Ridpath

PERSONAL REMEMBRANCES

HARRY BINSWANGER

This is an edited version of the tribute I gave to John at his 75th birthday party. John,

For forty-five years, you have not only been a close, dear friend, you have also been an inspiration. Your passion, your sense of drama, and above all your dedication to morality set you apart and give me the sense that there are still people in the world to whom ideas matter and what’s right is supremely important.

All your captivating stories fit a single theme: life is to be lived, not watched. From your days on the swim team, to your trip around the world, to so many Algonquin Park capers, to your times with Hollywood luminaries, to your trip up Mount Everest with Sir Edmund, you have embraced adventure, relished it, gotten the most out of it. That’s a lesson to all of us.

You’ve taught me many practical lessons as well, though often I’ve resisted them. Your generously provided Canoe Lake vacations taught me (approximately) how to build a cabin, how to rig a Laser sailboat, how to stain wood, and how to navigate Whiskey Rapids in a canoe.

As a teacher, you are peerless. You connect with students and inspire them— not just by the power of your lectures but also by the example you present in your person, becoming a hero-figure to your students. Routinely, former students, now middle-aged, stop you on the street, in restaurants, at airports to say they remember your classes with fondness and admiration. This is tremendously rare and must give you great satisfaction.

Your unyielding determination to complete your Nietzsche article, over so many years, shows your deep commitment to productiveness. As to honesty and integrity, well, they are too manifest to need comment: they are apparent to all who know you.

10 In Memoriam : : John B . Ridpath Ayn Rand Institute

We asked some of the many individuals whose lives were touched by John Ridpath to offer their remembrances.

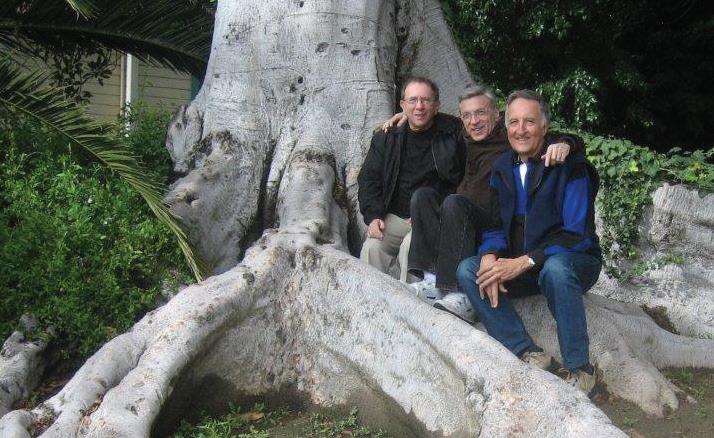

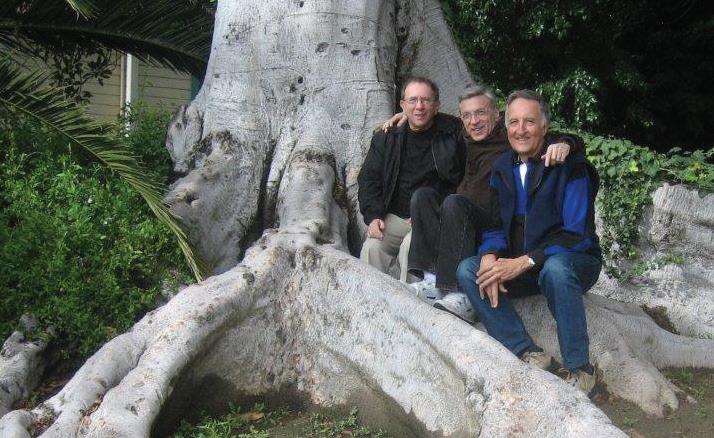

Mike Berliner, Harry Binswanger and John Ridpath in the Echo Park section of Los Angeles, across the street from the house where Ayn Rand’s husband, Frank O’Connor, lived with his brothers in the 1920s before the couple met. (Image courtesy Mike Berliner)

MIKE BERLINER

I met John in 1967, and we soon became close friends, hanging out at conferences and traveling together a bit in Europe, but particularly spending time together when, after his retirement from York University in 2001, he became a “snowbird” and spent winters near my home in Los Angeles.

Aside from many personal memories, one more intellectual memory stands out: In 2003 I began planning an anthology of topical chapters by different writers placing Ayn Rand in the history of philosophy, showing how she had solved the problems that had stumped (or been caused by) philosophers going back to the Greeks. Also, due to ongoing misconceptions about the relationship of Objectivism to Nietzsche’s philosophy, I asked John to contribute a chapter on that topic. John agreed but wasn’t satisfied with my suggestion that he use an article he’d written in 1986 for the Objectivist Forum. He told me that he’d learned a great deal more about Nietzsche and wanted a more thorough and convincing piece.

So began a lengthy process of rewriting and editing. A stumbling block arose when I had to abandon the book project, but John was not deterred. In fact, he was all the more motivated to complete the project, taking my suggestions very un-defensively, while standing up for what he thought was correct. Through it all, his motivation was justice: Nietzsche getting the justice he deserved for his irrational philosophy, but mainly justice to Ayn Rand by obliterating the claim that Objectivism was merely warmed-over Nietzsche, when in fact it is the opposite of Nietzsche. Eventually, an edited version, “Ayn Rand Contra Nietzsche,” was published in 2017 in the Objective Standard. It stands as a tribute not only to Ayn Rand but to John himself for his perseverance and, above all, his deep sense of justice.

JEFFERSON RIDPATH

As his eldest child, and the family member who shared with him a passion for ideas and deep understanding of Objectivism, there are countless stories and remembrances I could share with this audience. But the most important and personal is simply the profound impact that his independence, benevolence, and adventurous sense of life had on me.

11 In Memoriam : : John B . Ridpath Ayn Rand Institute

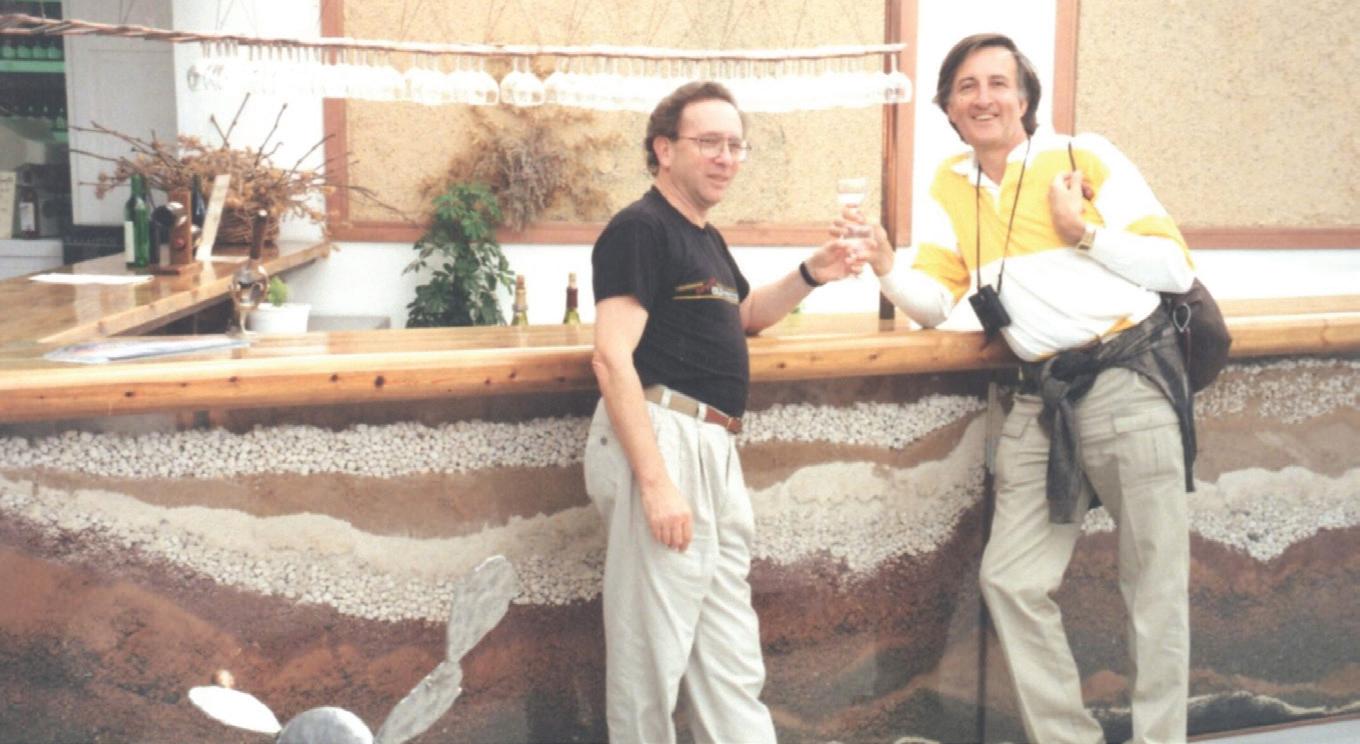

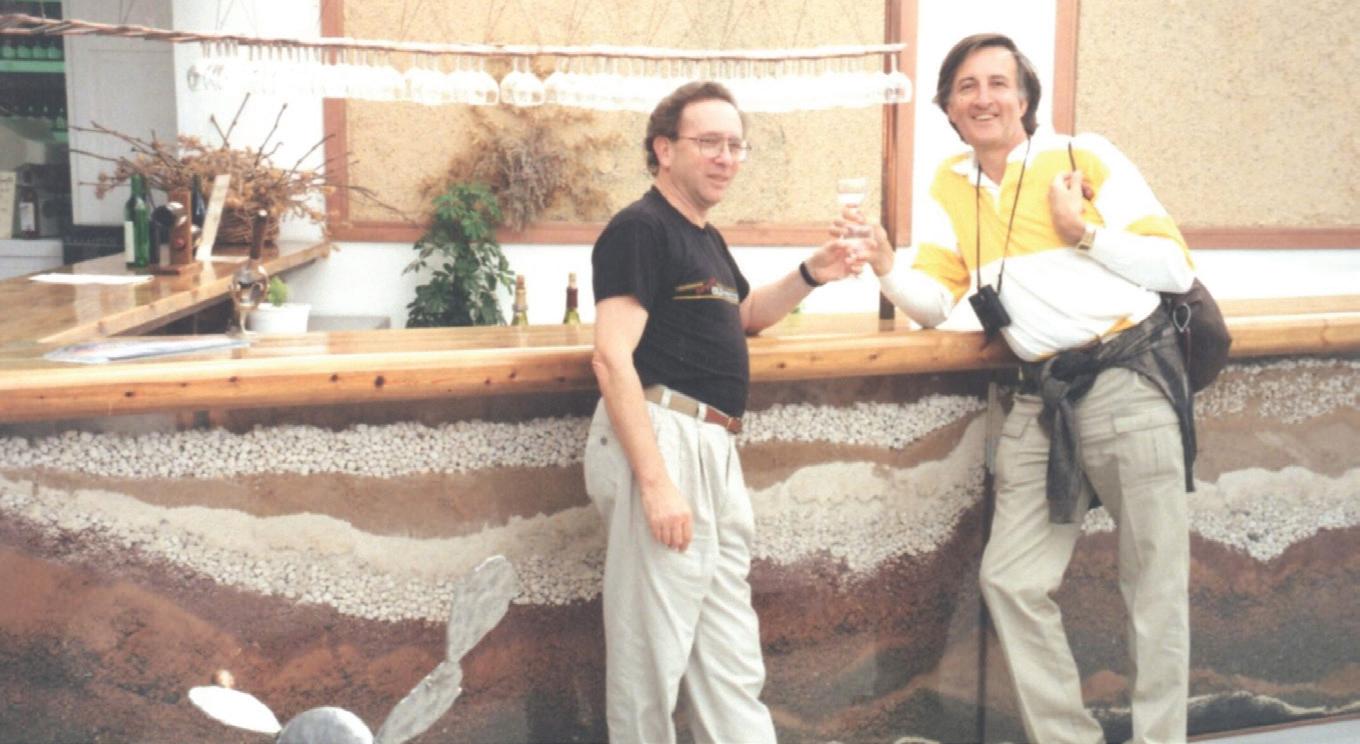

John Ridpath with Mike Berliner on Santorini, Greece. (Image courtesy Mike Berliner)

He was a legendary teacher, but the art of living a full and happy life can’t be taught in a lecture or classroom: it has to be learned by observation and example—over a long period of time. And I was fortunate to have a lifetime with a master.

From building cabins by hand and paddling the backcountry of our beloved Algonquin Park, to travelling the world together—first as a young family and later as friends and intellectual equals—my father’s confidence in himself and comfort in the world was ever-present and inspiring. In the words of a dear friend, on the occasion of his 75th birthday: “You are always in your world. You always have been.”

My father taught me—by lifelong example—how to be at home in the world.

SANDRA SHAW

These are slightly edited excerpts from my remarks published in the Intellectual Activist (July 2001) on the occasion of John’s retirement from teaching at York University.

Professor Ridpath brought to York a value that universities rarely see: entirely new fundamental ideas and a new approach to life.

He brought onto campus the revolutionary philosophy of Objectivism. He introduced Ayn Rand’s ideas as the climax of his freshman course, “Understanding Social Change,” an exploration of the impact of philosophical ideas throughout history. Undaunted by hostile faculty members and even by physical threats from student activists, he won the respect of students and faculty as a maverick and an intellectual contender. The name of Objectivism became known at York and at universities throughout Ontario.

Dr. Ridpath’s teaching of Objectivism at York was part of a deeper purpose to teach the value and methods of rational thinking.

His respect for the mind of a student was total. He treated his own thoughts and words very seriously, and he benevolently extended this intellectual self-regard to his students.

12 In Memoriam : :

Ayn Rand Institute

John B . Ridpath

Dr. Ridpath never simply taught something. He taught the importance of it. He showed, by the evidence of history and the present day, the life-and-death consequences of having rational or irrational ideas and methods of thinking.

Dr. Ridpath communicated the power of ideas by the example of his person. Most obvious was his physical presence: handsome, tall, well-dressed, he presented a vision of a man of stature. The clear, elementary virtues of his masculinity, uplifted posture, and open face contrasted sharply against a slouching campus culture.

In the end, Dr. Ridpath did much more than teach economics and the history of ideas at York. He demonstrated what it means to live for one’s own highest potential.

PETER SCHWARTZ

John had an easygoing but resolute, can-do personality. I remember that during the early days of ARI, we were very hesitant about fundraising. We didn’t want to be too aggressive in seeking donations. For example, we thought that asking someone for money more than once a year was unacceptable. John changed all that.

At a conference, there was a presentation about ARI’s activities—and John took over. He told the people there that if they wanted Objectivism to advance in the culture, they ought to contribute to ARI. He didn’t ask for money; he demanded it. He galvanized the audience and was able to raise a significant sum. From then on, our attitude about fundraising changed.

Dinner party at one of Ayn Rand’s historical residences in Los Angeles, California, on February 2, 2005, celebrating the centenary of Rand’s birth. Clockwise from left foreground: Judy Berliner, Mike Berliner, Peter Schwartz, Sandra Schwartz, Scott McConnell, Michael Paxton, Harry Binswanger, Donna Montrezza, John Ridpath, Kathy Cross and Jeff Britting. (Image courtesy Mike Berliner)

LINDSAY JOURNO

I first met John when I was a freshman at York University in the early 1990s, taking his course in intellectual history.

Because John was known as a professor nonpareil on campus, every seat in his lecture hall was filled; at times, it was standing room only. I can still picture him pacing up and

13 In Memoriam : : John B .

Ayn Rand Institute

Ridpath

down on the stage, gesticulating with his long slender fingers, presenting fundamental ideas in a fascinating, story-like manner—his rich baritone voice clear and impassioned.

In John’s class, academic study was never a dry intellectual exercise. He conveyed to his students that ideas held life-and-death importance, that we had agency over what we believed and how we lived, that our choices mattered.

The hallway outside John’s office was often lined with students who were waiting to ask questions, raise objections, and untangle confusions. Stepping inside that office was like entering a different world. In stark contrast to the beige, sterile spaces on campus, John’s office was an embodiment of his person. Decorated in forest green and rich mahogany, it was filled with expressions of his values: nature CDs recorded in his beloved Algonquin Park, a pickaxe from his Mount Everest adventure with Sir Edmund Hillary, photos of friends and family taken on his travels around the world, and shelves and shelves of books, including biographies of the Founding Fathers, novels by Hugo and Dostoevsky, and—of course—Ayn Rand’s books, prominently displayed.

Over the past thirty years, John became a treasured and integral part of my life. I grew to love and admire so much about him: his moral courage, his rationality, his benevolence. He was a valuer who relished his life and lived it to the fullest. I cherish my memories of sharing that adventure with him, and he is deeply missed.

DAVID SOKOL

I only knew John late in his career. I was introduced to him through a mutual friend, Dwayne Harty, an artist specializing in wildlife art. I had long been a student of Ayn Rand as well as a bit of a history buff in regard to America’s founding. These two passions—coupled with confusion as to how an amazing country such as the United States could seem to constantly slide down the path to collectivism—led me to search for individuals who could help me better understand how it was that Ayn Rand could predict America’s future nearly seventy years ago in her extraordinary book Atlas Shrugged. John Ridpath’s numerous insightful speeches, which I was able to acquire through various sources, led me to him. Dwayne made the introduction.

I had the good fortune to spend many hours with John over the next few years, in person and by phone. I found his ability to explain Ayn Rand’s philosophy and thought processes extraordinary in that he did not interject his own “spin” on things. He was more than willing to spend any time necessary to help me more fully understand who Ayn Rand was and how she thought. He quickly became a very important mentor to me.

Great, unbiased thinkers like John are hard to find today. Objectivism lost a great mind and a greater man with John’s passing.

14 In Memoriam : :

Ayn Rand Institute

John B . Ridpath

M. NORTHRUP BUECHNER

I met John in 1964 during our first semester of graduate economics at the University of Virginia, where we had several classes together. Very early, we found that we shared a passion for Ayn Rand’s philosophy, and I spent many evenings with John and his wife, Ginny, in the big house they had rented on the outskirts of Charlottesville.

In the spring of 1965, John invited me to drive with him to Toronto, where a Canadian bank had agreed to furnish information pertinent to a term paper he was writing. We left on a Friday morning and covered the five hundred miles in time for a late afternoon appointment.

Having driven all day, we were a little the worse for wear, our casual clothes quite rumpled, but John expected only a brief stop. The receptionist sent us upstairs to what turned out to be a huge meeting room with a massive polished oval table and leather chairs. No sooner had we entered the room than distinguished older men in dark suits started to file in—about twelve of them. It quickly became evident that the entire top management of the bank had been assembled to meet with John Ridpath.

Why did they do it? Only some years later did I grasp that they were keeping their doors open. John was a Canadian citizen whose family owned a major business in Toronto and who had been accepted into one of the top programs in graduate economics in the States. Some day, he might be important to Canada.

My mouth fell open. I was stunned. But John was calm, relaxed, at ease—which was even more amazing to me. It was then that I realized fully for the first time what kind of man John was. This was his world.

15 In Memoriam : : John B . Ridpath Ayn Rand Institute

John Ridpath gazing at the Acropolis from the patio of an Athens restaurant in 1997. (Image courtesy Mike Berliner)

JAMES LENNOX

I first met John Ridpath as a freshman at York University in 1967, where John was a lecturer in the Economics department. I had read The Fountainhead a year earlier, and it had an immediate and profound impact on me. But it was through my friendship with John that I was introduced to Objectivism as a systematic philosophy and a guide to life. The first taped lecture courses I listened to on Objectivism were in his home in Toronto. In my senior year as a Philosophy major at York, John hired me as a teaching assistant for his popular course on the history of Western culture. He was a charismatic lecturer with a deep, resonant voice and a dramatic, self-assured style of presentation, and the students loved his lectures.

John knew that my Philosophy honors thesis was a study of Aristotle’s De Anima, and he offered to ask his friend Allan Gotthelf if he would read it and give me comments. He agreed, and John arranged for us to meet and discuss it. Allan encouraged me to apply to graduate programs in philosophy.

John and I had two other things in common. We had both been competitive swimmers, and we had both grown up spending summers on the beautiful lakes of Ontario. While vacationing in the Algonquin Park area in 2019, as we were kayaking on a series of lakes inside the park, my wife and I realized that we were on Canoe Lake, where John had built the cabin that others have mentioned.

We remained in close contact while I attended graduate school at the University of Toronto. It was only much later that I came to fully appreciate how important John Ridpath was in helping me to make the choices that determined the future course of my life.

The Ayn Rand Institute fosters a growing awareness, understanding and acceptance of Ayn Rand’s philosophy, Objectivism, in order to create a culture whose guiding principles are reason, rational self-interest, individualism and laissez-faire capitalism—a culture in which individuals are free to pursue their own happiness.

The Ayn Rand Archives acquires, preserves, and provides access to Ayn Rand’s personal papers and related items. Our holdings form the most comprehensive grouping of Ayn Rand material in the world. The reading room, located in Santa Ana, California, is open to scholars, general writers, journalists and university students. The Anthem Foundation for Objectivist Scholarship provides grants for the benefit of academic professionals engaged in serious, scholarly work based on the philosophy and writings of Ayn Rand, and provides resources to others in academia interested in understanding her ideas. The Atlantis Legacy is a special program of the Ayn Rand Institute that acknowledges donors who have arranged bequests and other estate gifts to ARI, and highlights the importance of planned giving to the Institute’s ongoing success in advancing Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism. The John Ridpath Memorial Fund was established in cooperation with Dr. Ridpath’s family to provide scholarships for individuals to attend conferences on Ayn Rand’s ideas and to study at ARI’s Objectivist Academic Center, where they can get in-depth education from experts on Rand’s philosophy.

Edited by Tom Bowden. Copyright

© 2021 Ayn Rand

Institute.

16 In Memoriam : : John B . Ridpath Ayn Rand Institute

1936–2021

1936–2021