21 minute read

Graham Mason and Mark Belfield

The impact of diet and nutrition on the wellbeing of students at B&FC: A case study into students’ perceptions at Levels one and two regarding the importance of dietary intake on wellbeing.

Graham Mason and Mark Belfield

Advertisement

Introduction

This research project aims to evaluate the current dietary intake of students at Blackpool and the Fylde College (B&FC) and investigate its impact on mental wellbeing.

The current statistic of individuals in contact with mental health services between April 2019 and March 2020 were 1,380,240 people of which 237,088 were young people (NHS, 2020). The impact of Covid-19 has increased the consumption of long life convenience foods and ‘unhealthy’ junk foods in conjunction with an approximately 50% rise in the development of mental health issues (Robinson, 2020).

This project aims to evaluate the current level of wellbeing of students, at B&FC, and their current dietary intake, to determine if there is a direct correlation between nutrition and mental wellbeing. It then aims to establish the importance of developing interventions within the College environment to create awareness and provide information and guidance to improve mental wellbeing through nutrition.

Literature Review

The impact of diet on psychological wellbeing has been researched in a range of studies. These have investigated the consumption of specific food groups and eating behaviours and their direct impact on health and wellbeing, including brain development and cognitive function, while also considering external factors, including environmental, societal and socio economic. This review aims to analyse the current research in this area to support this research project.

The consumption of fruit and vegetables has a range of benefits on physical and mental health, however this review will focus on the benefits to individual cognitive function and wellbeing. The initial benefits of nutrition on wellbeing has been explored by Mujcic (2016), data was collected over a two year period through national survey of households. The analysis of the survey data correlated the intake of fruit and vegetables and an individual’s wellbeing. This study measured wellbeing through a life satisfaction survey and the quantity of fruit and vegetables consumed by individuals. It concluded that improvements in psychological wellbeing can be achieved through an increased intake of fruit and vegetables, with the higher the amount of fruit and vegetables consumed the greater the life satisfaction.

However, it is not only the positive impact of fruit and vegetables on a student’s wellbeing that must be analysed, but also the negative effect of specific food groups on wellbeing. The impact of refined carbohydrates on mood and wellbeing relates to their glycaemic index, which is the rate at which carbohydrates are metabolised and converted to glucose within the body. The westernised diet, which generates a high glycaemic load resulting in fluctuating blood glucose levels, has been demonstrated to increase depressive symptoms in otherwise mentally healthy volunteers in controlled experiments (Firth, 2020). Firth (2020) presents the concept of ‘dietary inflammation’ as the result of diets high in saturated fats, increasing inflammation of the hippocampus, which in turn is linked to various mental health conditions and cognitive decline, which have a direct impact on wellbeing. Adan (2019) supports these findings, identifying the negative impact that a high fat and sugar westernised diet has on cognitive function and an increase of anxiety-like behaviours.

With the consumption of refined carbohydrates having a negative effect on wellbeing, high sugar food groups also have a direct impact on synaptic activity and neuron communication within the brain, which in conjunction can impair cognitive ability and result in dysfunctions in insulin receptors, producing unstable energy metabolism (Agrawal, 2012). The impact of diet on the brain and cognitive function further analysed by Owen (2017). Owen focused on the hippocampus, the area of the brain related to memory learning and mood, with diet being associated with neurogenesis, the development neurons within the brain, within the hippocampus, correlating with an individual’s mood. This period in adolescence is critical, according to Lopez-Olivares (2020), as there are significant developments in emotional, cognitive and psychological dimesons which can directly affect quality of life and wellbeing. The adherence to a balanced and healthy diet during adolescence can have a positive impact on maturation of the brain, psychological wellbeing and the regulation of emotions.

Current research highlights the positive impact of the Mediterranean diet on wellbeing. This has been explored by Moreno-Agostino (2018), with analysis of positive affect (calm, relaxed and positive emotions) and negative affect (irritable, stressed, tense or depressed) states as a result of diet and their direct impact on wellbeing. The results conclude there was an affiliation between fruit and vegetable consumption and positive affect states, with a lower consumption of carbonated sugary drinks and full fat dairy products. In contrast negative affect states were found to be higher in diets which contained pastries, sweets, processed and red meats. However, the evidence in the report is not as clear, that the negative impacts on wellbeing associated with these food groups can directly affect wellbeing through their influence on physical health. Moreno-Agostino (2018) highlights a range of variables that can also impact an individual’s wellbeing besides diets, including tobacco usage, physical activity levels, socio-economic background and previous history of mental wellbeing, which must also be considered.

In the educational environment where this project is centred, the effect of diet on wellbeing is evident. Papier (2015) presents a range of evidence on students, which highlights the behaviour changes impacted by diet and in turn affecting health and wellbeing. This research presents the concept of a cyclic model in which stress initiates the consumption of refined carbohydrate and high fats foods, increasing the production of serotonin to reduce stress, but this diet has all the negative results as presented in previous research, resulting in the further consumption of an unbalanced diet. Stamp (2019) further investigates the impact of diet and wellbeing on mental toughness in university students and how their own mental toughness impacts diet and food choices, concluding that a balanced diet, including a focus on fruit, vegetables and fibre, results in higher mental toughness, which correlates to an increase in wellbeing.

Additional research on students in education (Peltzer 2017) documents not only the impact of food and the positive dietary behaviour of consuming breakfast every morning and its positive impact on life satisfaction and wellbeing, but the impact of sugar consumption in hot beverages. The report notes that students who did not consume sugar in tea or coffee recorded higher scores for happiness than individuals who consumed sugary hot

beverages and concluded that healthier dietary behaviour resulted in lower levels of mental distress and higher psychological wellbeing.

Lopez-Olivares (2020) analysis of the diets and wellbeing of university students, investigated their consumption of elements of the Mediterranean diet including olive oil, vegetables, fruit, legumes and whole grains, in conjunction with the analysis of the students consumption of processed foods, alcohol, sugary drinks and high fat commodities. The results highlighted once again the consumption of the Mediterranean diet and its elements have positive emotional and mental benefits and a higher quality of life and a high intake of red meat and processed meats have an inverse effect on wellbeing. Zurita-Ortega (2018) supports these finding of the benefits of the Mediterranean diet and social influences on diet and wellbeing, but their research on students noted that courses of study had a direct influence on the adherence to a balanced and nutritional diet. It was also concluded that an individual’s level of physical activity had a direct impact on diet, though it was noted there was no noticeable variations in the adherence to a balanced diet and religion.

Though there is a range of additional factors which can impact a student’s consumption of a diet beneficial to wellbeing, Utter (2017) examines the external influences on the diet of students and the impact of balanced family meals. The evidence presented the increased consumption of a balanced family meal was shown to correlate with increased emotional wellbeing, fewer depressive symptoms, and a reduction in emotional difficulties. This highlights the influence of family and social influences on nutrition and wellbeing.

Further analysis of beneficial diets presents the theory of the gut microbiome having a direct influence on neurotransmissions and behaviours associated with mental health disorders. The implementation of dietary changes which impact the microbiota can initiate beneficial cognitive developments (Malan-Muller, 2017) with changes in the intestinal microbiota improving wellbeing and a reduction in anxiety based behaviours. Though it must be considered that all beneficial microbiota are not dietary and environmental micro-organisms can also be a contributing factor to the microbiome.

There is a range of evidence which links the promotion of gut flora and microbiome for health, but further research is necessary (Taylor, 2019) as to which specific microbial profiles have a positive or negative impact on cognitive function and wellness. Though there is no identified microbial profiles which have a direct impact on wellbeing, research has highlighted specific food groups and diets which can have a positive effect. According to Hills (2019) the excessive consumption of carbohydrates in the form of added sugars, starches and refined grains has a negative impact on gut microbiota and a reduced bacterial diversity. Diets specifically highlighted by Hills (2019) for their beneficial impact on an individual’s microbiome, were the Mediterranean diet, noted for its predominant consumption of olive oil, vegetables, pulses, cereals and low glycaemic index carbohydrate, in conjunction with a conservative consumption of animal proteins in the form of meat and fish, and a lower intake of dairy, processed meats and refined grains which are over consumed in a westernised diet.

In conclusion, an increasing range of evidence supports the concept of diet impacting an individual’s wellbeing and also being critical to brain development in adolescents. A large percentage of research praises the benefits of the Mediterranean diet, which is centred on the consumption of fruit, vegetables, pulses, cereals and dietary fibre, with a lower intake of animal products and refined carbohydrates. The research highlights the negative affect of sugary drinks, refined grains and processed foods, therefore this project will focus on these food groups and analyse their impact on the students’ wellbeing.

Methodology

This quantitative research project will focus on the collection of primary numerical data to expose trends, patterns and relationships between data sets (Albers, 2017). This research was centred on two forms of primary data. Initially a variation of a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was used to analyse the diets of students, as it enables respondents to detail how much and how often they consumed specific food items. The FFQ is regarded as a simple, time efficient and cost effective method to collect dietary data (Shim, 2014), with the flexibility to be tailored for this study focusing on specific food groups and nutrients. To facilitate the collection of data a short food questionnaire (SFQ) was utilised, which reduced the usual 150 questions on a FFQ to approximately 50 questions on the SFQ. Nikniaz (2017) concluded that a SFQ was ‘reasonably good in estimating food groups and nutrients’ and is applicable for ranking food group consumption. Though consideration must be given to the reliability of any type of FFQ, Golley (2016) highlights variables including perception of portion size and the cognitive ability to accurately recall food consumption and patterns. The SFQ aimed to address these potential variables through providing diagrammatic representation of single portions and limiting food groups to enable the focus on specific foods.

The wellbeing of students was measured utilising the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS), it is a reduced revision of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). The SWEMWBS consists of seven positively worded statements about their thoughts and feelings over the previous two weeks, which is then converted to scores providing an insight to the individual’s wellbeing. The SWEMWBS has been validated in Europe in various population studies including clinical, adolescents and minority groups Koushede (2019). The SWEMWBS was selected for its increased completion rates, lower participant burden, focus on positively worded questions avoiding the negative aspects of mental or physical health and relative similar performance compared to the full WEMWBS (Fat, 2017). The utilisation of the SWEMWBS was evaluated by Ringdal (2017), which confirmed its suitability for use with adolescents, and its ability to capture the current state of mental wellbeing in participants, through focusing on eudaimonic wellbeing, the happiness achieved through meaning and purpose.

All research was collected online utilising Microsoft Forms and completed remotely by students within online sessions in various curriculum areas to adhere to government Covid-19 legislation of ‘National Lockdown’ and all FE learning being delivered remotely. Overall 100 questionnaires were issued to Further Education students across numerous programmes of study, with a completion rate of 100%.

Results

The aim of this research was to establish if nutrition had an impact on the current level of wellbeing of Further Education (FE) students.

Wellbeing

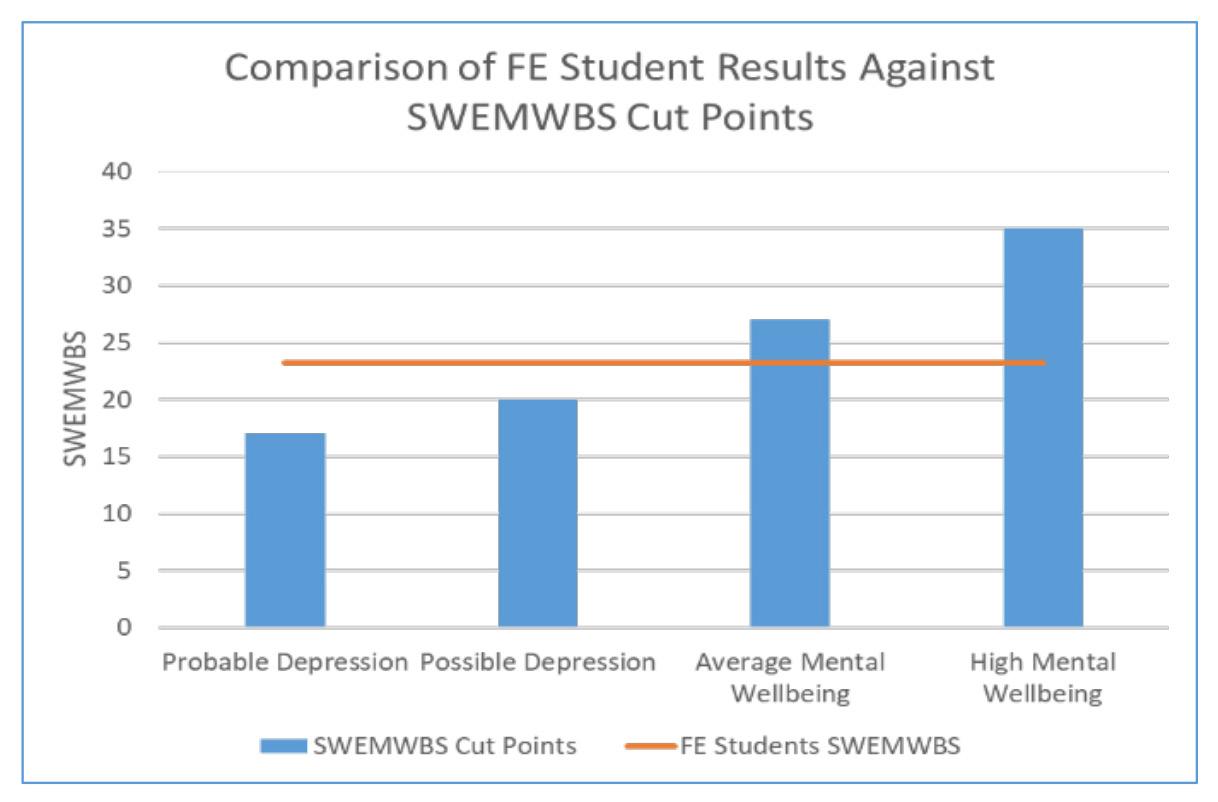

The primary data collected for the current measure of the wellbeing of student’s, utilising the SWEMWBS, presents the current level of wellbeing of students at 23.2 out of a potential 35 on the SWEMWBS scale. In relation to the SWEMWBS Population Norms in Health Survey for England data, (2011) which highlights the mean national level of wellbeing recorded as 23.6, resulting in FE students recording a lower than average score when compared to the national average. The average data is also presented against the established cut points (Warick.ac.uk, 2021), with ‘17 or less for probable depression, 18-20 for possible depression, 21-27 for average mental wellbeing and 28-35 high mental wellbeing’, fig.1 presents the average score for FE students against the established cut points.

Fig 1

Fig.2 Fig.3

Further analysis of the individual statements presents additional detail on the current wellbeing of FE students. Significant results obtained from the SWEMWBS data in regards to the statement ‘I’ve been feeling relaxed’ (fig.2) highlights that 68% of participants feel relaxed some of the time or less, including 28% of participants who rarely felt relaxed. Data regarding the expected positive individual future prospects, the statement ‘I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future’ (fig.3) presents finding that only 52% of students were sometimes optimistic about the future, with a total of 65% feeling optimistic some of the time or less about their future.

Nutrition

The data obtained through the short food frequency questionnaire was collated into several categories to establish the intake of refined processed foods, refined carbohydrates, consumption of fruit and vegetables, sugary beverages and high fat foods. The results obtained for the consumption of processed meats, in comparison to fresh fish, which is a key element of the Mediterranean Diet, highlight a low dietary intake of oily fish, with 73% of students rarely or never consuming oily fish. Fig.4 presents the comparison, one portion a week or more of processed meats to fresh fish consumption. The results document a 70.7% weekly consumption of processed pork in conjunction with 47% of students consuming one or more servings of fried chicken products, in comparison to a 12% weekly consumption of oily fish. Further analysis of 2-3 portions a week of processed meats, the findings show 23% of students are consuming 2-3 portions of fried chicken and 29.3% consuming 2-3 portions of processed pork products each week.

Fig. 4 Fig. 5

In the results of dietary intake of refined carbohydrates in comparison to whole grains (fig.5), the evidence documents that all variations of refined grains were consumed in a higher volume than whole grain products. The consumption of white bread recorded the highest in dietary intake with 26% of students reporting they consume 4-6 portions each week and 35.6% of students consuming chips 2-3 times a week with 7.1% consuming chips 4-6 times a week. In comparison to whole grain products 64.6% of students rarely/never consuming oats, 79.6% of student’s rarely/never consuming brown rice and 81.6 rarely/never consuming brown pasta.

The results recorded for the weekly dietary consumption of fruit (fig.6) and vegetables (fig.7) compare the consumption of 2-3 portions of each item per week in relation to never consuming that specific fruit or vegetable. The results for fruit consumption highlight 27.3% of students consuming 2-3 apples a week in comparison to 24.2% never/rarely consuming apples, this result for apples was the only figure for fruit consumption in which 2-3 portions a week was higher than the rarely/never consumed. The results of consumption for the remaining fruits show that the rarely/never for fruit consumption was higher than 2-3 portions a week, notable figures for rarely/never consumption of fruit being, oranges 42.4%, strawberries 37.4% and dried fruit 72.4%.

Fig. 6

The results for vegetable consumption (fig.7) continues to document a low dietary intake of fruits and vegetables, with only two vegetables having a higher consumption rate of 2-3 portions compared to rarely/never consumed were carrots (32%) and broccoli (31%). The results for rarely/never consuming vegetables reported a low consumption of mineral rich green vegetables with rarely/never consumption of cabbage (40.4%), courgettes (77%), green salad (34%), green beans (47%). Though in contrast, the weekly consumption of 2-3 portions of peppers (31%), tomatoes (25%) and sweetcorn (24.5%) was above average in comparison to fruit and alternative vegetables.

Fig.7

Discussion

The aim of this research was to establish if the nutrition of FE students had an impact on wellbeing, through data obtained through the Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale in conjunction with a short food frequency questionnaire. The results for the current level of wellbeing provided a score of 23.2 points on the SWEMWBS, this is below the national average and utilising the established cut points (Warwick.co.uk, 2020) presents the FE students below the midpoint for average mental wellbeing. The food frequency questionnaire documents a large percentage of students are not consuming enough wholegrains and the low intake of a variety of fruit and vegetables with a considerable amount of students never/rarely consuming any types of fruit and vegetables.

The most significant findings of this study is the below average mental wellbeing score on the SWEMWBS which is only 3.2 points from the cut points for possible depression. This result, in conjunction with a low intake of fruit and vegetables and preferred intake of processed meats, builds on existing evidence of Mujcic (2016) that the consumption of fruit and vegetables can have a direct impact on mental wellbeing.

The research of Zurita-Ortega (2018) and Lopez-Olivares (2020) document the positive impact of the Mediterranean diet which is centred on the consumption of minimal animal product, fresh fish, whole grains and fruit and vegetables. The data obtained presents the opposite of the Mediterranean diet and consists of a low consumption of whole grains in conjunction with the low intake of fruit and vegetables and this supports academic research that diet can correlate to psychological wellbeing.

The high consumption of refined carbohydrates and processed foods, in comparison to the low consumption of whole grains and fruit and vegetables, has a direct impact on saturated fat consumption, glycaemic index and the glycaemic load in student’s diets, producing unstable blood glucose levels and dietary inflammation, which can be a contributing factor to the lower than average mental wellbeing of students. The negative effect of refined carbohydrates are highlighted in the SWEMBS results which recorded 28% of students rarely feeling relaxed, potentially leading to anxious behaviours, and 45% of students only thinking clearly some of the time. These results support the findings of Firth (2020) and Adan (2019), whose research supports the finding of the negative effects of a processed westernised diet on mental function and wellbeing.

The results of SWEMBS could also reflect the situation presented by the global pandemic with only 24% of students often feeling optimistic about the future, 27% of students often feeling useful and 24% of students rarely feeling close to others. These reflect the current temporary closure of industry and its impact on employment and the loneliness from isolation.

This research has a range of limitations. The reliability of this data is impacted by the limits of food frequency questionnaires and the ability for adolescents to recall dietary intake. It also fails to take into account additional factors which can impact mental wellbeing: previous mental illness, smoking and levels of physical activity (Moreno-Augustino 2018). The socio-economic status of students could impact the results with the simplified access to convenience and ‘Junk’ foods and the perceived expense of wholefoods. This could be further impacted by the global pandemic which has negatively impacted the visitor economy, central to the employment of individuals and families in Blackpool. The analysis of this research was limited by the quantity of data obtained through the study and constraints of research production, therefore failing to fully utilise all data.

Further research should focus on establishing a control group to then determine if positive alterations on diet do have a positive impact on wellbeing and to analyse specific dietary choices and their impacts. Future studies need to analyse eating habits through a range of data collection methods, while also considering nutrition and culinary knowledge, and the parental influence on a student’s diet through ability and affordability.

These findings present supporting data on the impact of nutrition on wellbeing and the results provide a deeper insight to the wellbeing of students in Further Education highlighting negative dietary choices and their impact.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to investigate the impact of nutrition on wellbeing through the quantitative data obtained in the SWEMBS and the food frequency questionnaire. These results and the supporting literature conclude that nutrition can have a direct impact on FE student’s mental wellbeing.

This research clearly illustrates to impact of poor nutrition on mental wellbeing and demonstrates the need for interventions to provide information and develop an understanding of the positive impact a balanced and nutritional diet can have on mental wellbeing. Based on these conclusions, nutritional advice should highlight the positive influence and benefits healthier food choices can have on mental health.

This research contributes to the academic literature on the wide range of modifiable variables which can have a direct impact on wellbeing. It provides an insight into the dietary intake of FE students and its impact. Future research on this topic should focus on beneficial nutritional interventions and how they can improve the wellbeing of students.

References

Adan R.A.H., Van Der Beek, E.M. & Buitelaar, J.K. et al. (2019). ‘Nutritional psychiatry: Towards improving mental health by what you eat’ European Neuropsychopharmacology, pp. 1-12. Agrawal, R. , Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2012). ‘Metabolic syndrome’ in the brain: deficiency in omega-3 fatty acid exacerbates dysfunctions in insulin receptor signalling, R>A and cognition. J. Physiol. 590, 2485–2499. Albers, M.J. (2017) ‘Quantitive Data Analysis – In the Graduate Curriculum’. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication. Vol. 47(2) pp. 215-233. Fat L. N., Scholes S., Boniface S., Mindell, J., Stewart-Brown, S. E. (2017) ‘Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the Health Survey for England’. Qual Life Res. 26:1129–1144 Firth J., Gangwisch J.E., Borsini A., Wooton R.E., Mayer E.A. Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing. (2020) The BMJ. 369:m2382 Golley R.K., Bell L.K., Hendrie G., Rangan A., Spence A., McNaughton S.A., Carpenter L., Allman-Farinelli M., de Silva A., Gill T., Collins C., Truby H., Flood V.M. & Burrows T. (2016) ‘Validity of short food questionnaire items to measure intake in children and adolescents: a systematic review’. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. Koushede, V. et al. (2019) ‘Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: Validation of the original and short version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings’ Psychiatry Research. Vol. 271. pp. 502-509. Lopez-Olivarer M., Mohatar-Barba M., Ferndandez-Gomez E., Enrique-Miron C. (2020) ‘Mediterranean Diet and the Emotional Well-Being of Students of the Campus of Melilla (University of Granada)’. Nutrients 2020, vol. 12 Malan-Muller, S. et al. (2017). ‘The Gut Microbiome and Mental Health: Implications for Anxiety- and Trauma-Related Disorders’. Journal of Integrative Biology. Vol. 21(0). Moreno-Agostino, D., et al. (2018). ‘Mediterranean diet and wellbeing: evidence from a nationwide survey’ Psychology & Health. Mujcic R., Oswald A.J. Evolution of Well-Being and Happiness After Increases in Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables. (2016) AJPH Research. 106:8. NHS (2020) ‘Mental Health Services Monthly Statistics Final March 2020’ available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/ data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-services-monthly-statistics accessed 7th June 2021. Accessed 10th March 2021. Nikniaz,L., Tabrizi, J.,Sadeghi-Bazargani, H., Farahbakhsh, M., Tahmasebi, S., Noroozi, S. (2017) ‘Reliability and relative validity of short food frequency questionnaire’. British Food Journal. Vol. 119:6. Owen L., Corfe B. The role of diet and nutrition on mental health and wellbeing. (2017). Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 76, 425-426. Papier, K., Ahmed, F., Lee, P., Wiseman, J. (2015) ‘Dietary behaviour among first-year university students in Australia: Sex differences’. The international Journal of Applied and Basic Nutritional Science, 31. pp. 324-330. Peltzer, K., Pengpid, S. (2017) ‘Dietary Behaviors, Psychological Well-Being, and Mental Distress Among University Students in ASEAN’. Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences. Robinson, E. et al. (2020) ‘Obesity, eating behaviour and physical activity during COVID-19 lockdown: A study of UK adults’ Appetite. Vol. 156

Ringdal, R., Eilerten, M.E.B., Bjornsen, H.N., Espnes, G.A. Moksnes, U.K. (2017). ‘Validation of two versions of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale among Norwegian adolescents’. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 1–8. Shim, J-S., Oh, K., Kim, H.C. (2014) ‘Dietry assessment methods in epidemiologic studies’. Epidemiology and Health. Vol. 36. pp. 1-8. Stamp, E., Crust, L., Swann, C. (2019) ‘Mental toughness and dietary behaviours in undergraduate university students’ Appetite, Vol. 142. Taylor. V.H. (2019) ‘The microbiome and mental health: Hope or hype?’ Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 44(4). Utter, J. & Denny, S. et al. (201) 7‘Family Meals and Adolescent Emotional Well-Being: Findings from a National Study’. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behaviour. Vol 49. pp. 67-72. Warwick Medical School (2020) ‘The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scales – WEMWBS’ Available at: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs/using/howto/wemwbs_population_norms_in_ health_survey_for_england_data_2011.pdf . Accessed 29th March 2021.

Zurita-Ortega, F., Roman-Mata, S.S., Chacon-Cuberos, R., Castro-Sanchez, M., Muros, J.J. (2018) ‘Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Physical Activity, Self-Concept and Sociodemographic Factors in University Student’. Nutrients. 10:966.