Bardian Bard College Spring 2006

Writing Africa Food Webs as Predictive Tools Clerking for Chief Justice Ginsburg: Anna-Rose Mathieson ’99 Confucian Enlightenment

Professor Maria Simpson discussing the human skeleton with a parent after a Family Weekend lecture

Board of Governors of the Bard–St. Stephen’s Alumni/ae Association Dr. Ingrid Spatt ’69, President Michael DeWitt ’65, Executive Vice President Walter Swett ’96, Vice President Maggie Hopp ’67, Secretary Olivier teBoekhorst ’93, Treasurer David B. Ames ’93 Robert Amsterdam ’53 Claire Angelozzi ’74 Judi Arner ’68 David Avallone ’87 Dr. Penny Axelrod ’63 Cathy Thiele Baker ’68, Nominations and Awards

Committee Cochairperson Belinha Rowley Beatty ’69 Eva Thal Belefant ’49 Dr. Miriam Roskin Berger ’56 Jack Blum ’62 Carla Bolte ’71 Erin Boyer ’00 Randy Buckingham ’73, Events Committee Cochairperson Jamie Callan ’75 Cathaline Cantalupo ’67 Charles Clancy ’69, Development Committee Cochairperson

Peter Criswell ’89, Career Connections Committee Cochairperson Arnold Davis ’44, Nominations and Awards Committee Cochairperson Kit Kauders Ellenbogen ’52 Joan Elliott ’67 Naomi Bellinson Feldman ’53 Barbara Grossman Flanagan ’60 Connie Bard Fowle ’80, Career Connections Committee Cochairperson Diana Hirsch Friedman ’68 R. Michael Glass ’75 Eric Warren Goldman ’98, Alumni/ae House

Construction of The Gabrielle H. Reem and Herbert J. Kayden Center for Science and Computation

Committee Cochairperson Rebecca Granato ’99, Young Alumni/ae Committee Cochairperson Charles Hollander ’65 Dr. John C. Honey ’39 Rev. Canon Clinton R. Jones ’38 Deborah Davidson Kaas ’71, Oral History Committee Chairperson Chad Kleitsch ’91, Career Connections Committee Cochairperson Richard Koch ’40 Erin Law ’93, Development Committee Cochairperson Cynthia Hirsch Levy ’65 Dr. William V. Lewit ’52

Peter F. McCabe ’70, Nominations and Awards Committee Cochairperson Steven Miller ’70, Development Committee Cochairperson Abigail Morgan ’96 Molly Northrup Bloom ’94 Jennifer Novik ’98, Young Alumni/ae Committee Cochairperson Karen Olah ’65, Alumni/ae House Committee Cochairperson Susan Playfair ’62, Bard Associated Research Donation (BARD) Committee Chairperson Arthur “Scott” Porter Jr. ’79 Allison Radzin ’88, Events Committee Cochairperson Penelope Rowlands ’73

Reva Minkin Sanders ’56 Roger Scotland ’93 Benedict S. Seidman ’40 Donna Shepper ’73 George Smith ’82 Andrea J. Stein ’92 Dr. Toni-Michelle Travis ’69 Jill Vasileff MFA ’93, MFA Liaison Marjorie Vecchio MFA ’01, MFA Liaison Samir B. Vural ’98 Barbara Wigren ’68 Ron Wilson ’75, Men and Women of Color Network Liaison

Dear Alumni/ae and Friends, This letter is about connecting. Perhaps it was a brilliant red leaf fluttering at your feet and a sudden whiff of crisp fall air; or the first few instantly recognizable measures of “Walk on By” drifting out of the radio; or the sound of a waterfall that made you close your eyes to capture the vision of that waterfall . . . and there you were, for a few brief moments in your busy, rushing-on-by life, back at Bard. For the past two years I have had the opportunity to attend the Life After Bard dinners on campus, where alumni/ae return to talk with current students about their career paths, choices they made along the way, and, essentially, how they got from here to there. Consistently, a theme has emerged from these conversations: that of linkages and the importance of maintaining Bard connections, be it for personal or professional reasons. It is clear that the Bard community is important to these alumni/ae and they cherish the friends they still hold close after many years. The years go by and we do lose touch. It is quite possible that your only connections with Bard at this time are issues of the Bardian, or an annual contribution (thank you!) to the Bard alumni/ae fund. However, I am delighted to tell you that you do not have to lose the academic and supportive community of Bard. There are many ways you can maintain and strengthen your associations. There is an active website at www.bard.edu that offers you the opportunity to connect with classmates and other Bardians. Click on “Alumni/ae” and go to Online Community. Once there, you can register and log on to find an alumni/ae directory, websites of fellow Bardians, and a message board. Want to send a unique message? Click on “Send a Postcard” and get an array of Bard landscapes and buildings to accompany your message. Want to send news for publication in the Bardian? Click on “Class Notes.” Looking for your first job or considering a career change? Click on “Services” and access the college’s Career Development Office. This office also supports the collegecentral.com/ bard site, on which you can post job or internship offerings or sign up to be a mentor to a current student. As a mentor you can choose a wide range of personally fulfilling opportunities, ranging from being a listening ear to assisting with a job placement. The alumni/ae website offers you details of upcoming events. There is also information on ways to give to Bard—including the alumni/ae fund, gifts of appreciated securities, and planned giving—to support current and future students, and thus future members of the Bard alumni/ae community. Take a moment. Sit back. Is there a particularly poignant memory you have cherished? Is there a little stirring of desire to take the “then” and make it the “now”? Then reconnect and come back to Bard! Learn about all the new and exciting programs and initiatives that have made Bard a major force in liberal arts education in the 21st century. Be a part of it. Ingrid Spatt ’69, Ed.D., President, Board of Governors, Bard–St. Stephen’s Alumni/ae Association

Bardian

24

8

18

SPRING 2006 Features 4

Roger Scotland ’93 Inspires City Kids

6

Supreme Clerkship: Anna-Rose Mathieson ’99

8

Writing Africa: In Search of “A Balance of Stories”

14

MAT Program Graduates Make Marks in the Inner City

16

Looking Homeward: An Internship of Consequence

18 20 24

26

Science, Technology, and Society: Furthering Cross-pollination among Academic Fields

28

To Bear Witness: Medical Relief in Kashmir

32

Holiday Party

Departments 34

Books by Bardians

38

On and Off Campus

52

Class Notes

68

Faculty Notes

The Golden Rule’s Contemporary Relevance Food Webs of the Past, Present, and Future Dissonant Issues about World Music

A MOTIVATIONAL

SLAM DUNK Roger Scotland ’93 Inspires City Kids

When people talk about Roger Scotland ’93, they speak of his willingness—indeed, his determination—to go out of his way to help others. “In basketball camp, he was one of the counselors, and to my amazement, he was friendly,” recalls David McClure, who was an overwhelmed fourth-grader when he met Scotland a decade ago. Now 19 and a sophomore at Duke University, McClure still sees Scotland as a mentor. He remembers being 15 years old and taking part in a 3-on-3 game with men in their 20s. Scotland was playing too. “I was real intimidated, and Roger just pulled me aside and told me, ‘Don’t be afraid; you’re better than they are.’ He made me realize I could instill confidence in myself.” Fittingly, Scotland works with youth. He is deputy director for citywide education and youth services in New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s office; before that, he ran one of the city’s summer youth employment programs. Thanks in part to Scotland, young employees now can receive their pay through a debit-card system. He also has worked for the Madison Square Boys & Girls Club and directed fund development and special projects for Harlem Congregations for Community Improvement (HCCI). He was himself mentored by many. “I grew up in East New York, Brooklyn, and never had consistent access to afterschool programs,” says Scotland, reached at his office in lower Manhattan. “When I was looking to go to college, I didn’t get sound counseling in school. It was through a basketball coach

that I heard about Bard. . . . My models have been people who didn’t have to be involved with young adults, but were—the late Reverend Dr. Preston R. Washington, Charles McDuffie, Kurt James, Lawrence Smith, and Archdeacon and Mrs. Bernard O. D. Young. ” One coach, Neil Woodard, involved him in Operation Athlete, a program run by the not-for-profit Henry Street Settlement, which tried to form college careers for teenagers interested in improving themselves. When Scotland heard about Bard, he recalls “griping” that he couldn’t afford carfare for the visit. Operation Athlete’s director, James Robinson, gave him and his mother $100 for the trip. “When I got back, he died,” Scotland recalls. “I knew I had to go to Bard,” which he did through the Higher Education Opportunity Program (HEOP). As an undergraduate, Scotland helped out with the Special Olympics, while playing varsity basketball (he was captain from 1991 to 1993). “I’ve always acted through the examples others have set,” he says. “My grandfather, a deacon in the church, was a maintenance worker in a Coney Island housing development; no matter what his situation, he always helped others.” Woodard remembers Scotland, who was 16 at the time the two met, as both organized and smart: “He was my assistant coach in Operation Athlete after he graduated from Bard, and he taught the kids how to think. He made the game as cerebral as it is physical.” Woodard adds, “He was motivational and inspirational for those kids. He would tear you down, then pull you back up, which is necessary because there is a lot of cockiness on the basketball court.” Scotland grew up with his mother and two siblings; his parents divorced when he was young. His mother, a manager at Citibank, worked an additional part-time job to support her three children while attending community college. Scotland himself is divorced with no children, and has what he calls two “vices”: his two Alaskan Malamute dogs and the antique cars that he restores. He strongly believes that, nowadays, adults increasingly ignore or allow themselves to be intimidated by young people. “If you see children doing something they shouldn’t, go out and talk with them,” he says. “Many adults don’t take the time to engage our kids; many people are scared of children, who try to take advantage. As Leon Botstein wrote in Jefferson’s Children, teenagers have a great deal of perspective, intellect, and curiosity.” At HCCI, Scotland’s first job after Bard, “I was extended a tremendous opportunity to be involved in the holistic reha-

bilitation of Harlem,” he recalls. “But I realized no one would listen to me with only a B.A.” So he enrolled in a Ph.D. program in history at Columbia. Still at HCCI, he met a consultant, Herb Lowe, who later recruited him for the Madison Square Boys & Girls Club, where Scotland ultimately became director of marketing and community relations and where he learned valuable lessons about life, business, and stewardship. He began working for New York City in June 2002. “I saw him in action in the not-for-profit world and in government,” says Ernie Hart, former chief of staff to the deputy mayor for policy and now assistant vice president for employee and labor relations at Columbia University. “At the Department of Youth and Community Development, he helped to start up and maintain day-to-day relationships in a program that involved banks, contractors, parents, and youth. He made certain the debit card program was successful. The purpose was to make it easier for the city’s bookkeeping, but it also gave kids experience in financial management.” Scotland is involved with promoting a uniform and responsive policy toward youth and families. His focus is on “disconnected youth”—ages 16 to 24, who are neither in school nor work—and young adults negotiating the criminal justice system. “We are trying to better coordinate services so those who fall through the cracks early in life find . . . access to workforce development programs, life-skills training, and supportive interventions,” he says. In the midst of this busy life, Scotland found himself diagnosed in 2001 with Guillaume-Barre Syndrome, an immobilizing disorder that later often afflicts sufferers with chronic fatigue. (He conducted negotiations on a tentative property closing from his bed in an intensive care unit.) He says the experience, like so many others in his life, affected him deeply: “It gives you a better appreciation for the things you take for granted. I’d been an athlete all my life and I couldn’t even do a toe raise. Now I always look at programs with an eye toward people with special needs.” Another example of his concern for youth is his continuing connection with the Bard campus through his participation on the Board of Governors of the Bard–St. Stephen’s Alumni/ae Association. “Since my childhood and my time at Bard, I have always had in me the examples others have set,” Scotland says. “Today’s youth could learn much from intergenerational contact and greater focus—both by them and by the adults who are supposed to prepare them for successful adulthood.” —Cynthia Werthamer 5

SUPREME CLERKSHIP Anna-Rose Mathieson ’99 Serves the Highest Court They are the highest clerks in the land. Young, bright, diligent, and highly motivated law school graduates, they are handpicked by the nine Justices of the United States Supreme Court for one-year terms characterized by “long hours wading through eye-glazing paperwork,” as Charles Lane put it in the Washington Post. Working well behind the scenes, and outside the hot glare of media scrutiny, they help the Justices pore through certiorari applications (applications requesting the Supreme Court to review lower-court decisions) and assist in researching and writing judicial opinions. In July 2005, a Bard graduate was welcomed into the elite corps of Supreme Court clerks. Anna-Rose Mathieson ’99, a 6

native Oregonian who earned her bachelor’s degree in philosophy in Annandale and then went on to graduate first in her class at the University of Michigan Law School, was selected by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to serve as one of four clerks on her staff. For Mathieson, it was—as it no doubt must be for any clerk selected—a case without any experiential precedent. “Nothing can really prepare you for the substance of a Supreme Court clerkship—all you can do is jump in and hang on as the almost vertical learning curve goes up and up,” she says. “But it helped that I’d been in several other situations that were also intense from the outset. For the eight months before my clerkship, for instance, I worked at the

[Washington, D.C.] law firm of Williams & Connolly. I started in November, and was immediately put on a big criminal case that was going to trial in February. It was an amazing learning experience: for all of February, our trial team camped out in a Manhattan hotel and threw every waking hour into defending our client.” While clerking for the nation’s highest court may present an unparalleled learning opportunity, Mathieson cannot divulge the details: she and her fellow clerks are bound by the strictest of confidentiality agreements. The Supreme Court, as an institution, places a premium on discretion; while details about the size of Mathieson’s workload, say, or the amount of hours she logs might appear to be trivial, even such humdrum minutiae about the Court’s inner workings are not generally made public. Nothing prohibits her, though, from discussing how her many and varied interests dovetail with her legal career. “Right after my clerkship interview with Justice Ginsburg, I went to India for a couple of months,” she relates. “Not to see the tourist sights—I’d already spent several months doing that, being awed by India’s beauty and history, and trying not to be overwhelmed by the sensory overload of sights, smells, and sounds. Instead, this trip was to learn about India’s legal system. I wasn’t planning to have the experience contribute to my professional development in any specific way; nor did I have any contacts there, or even a plan about how I was going to proceed. I just hopped on a flight, showed up at one of the law schools in Bombay, and started talking to professors and students.” The adventure proved to be as enlightening as it was enjoyable. “I sat in on several law school classes and even taught a contracts class; watched wig-bedecked lawyers argue in several types of courts; talked to law clerks, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and law firm partners; and read the Indian penal code while sitting on a roof overlooking the chaos of Bombay,” she says. Her Indian sojourn helped Mathieson gain an appreciation for the evolution of criminal law. “Both Indian and American criminal law grew out of the same British common law roots, and both changed and adapted in response to different histories, cultures, and governmental structures,” she says. “It was just fun to learn about something interesting and get to design my own curriculum. [It’s] the sort of thing I would never have done had I not gone to Bard.” The above account makes abundantly manifest those personal qualities—confidence, resourcefulness, amiability,

and a keen intelligence wedded to a boundless curiosity— that have stood Mathieson in such good stead and make such a lasting impression on those who encounter her. “Do I remember her? We all do—she is unforgettable,” says William Griffith, professor and director of the Philosophy Program at the College. “She was absolutely an exceptional student—one of the very best we have ever had in the department. We all thought she might do spectacular things. Now, it looks as though she has.” Garry Hagberg, James H. Ottaway Jr. Professor of Aesthetics and Philosophy, was Mathieson’s adviser on her Senior Project. “What emerged from a flurry of highly focused work was an award-winning, truly exceptional piece of writing on philosophical issues in legal theory,” he says. “We in the Philosophy Program are very pleased by, and very proud of, her remarkable achievements.” In case your image of a law clerk is that of a vaguely Dickensian character, haggard and twitchy from squinching over intimidating piles of papers and rarely seeing daylight, let it be noted that Mathieson does have a life outside of law. She has, at one time or another, been an avid runner, fencer, rower, and white-water rafter; she has a passion for art history and theater; and she is an insatiable traveler, having visited, to date, more than 30 countries and all 50 states. Mathieson has swum with piranhas in the Amazon, trekked the Inca trail, waded through two kilometers of mud to cross the Laotian-Chinese border on foot, and put the finishing touches on her law school admissions essay in an Internet café in Bangkok. In July, Mathieson will complete her service with Justice Ginsburg and move on. She will be in an enviable position; according to Legal Times, former Supreme Court clerks are highly prized and aggressively recruited by law firms. For her part, Mathieson has no immediate plans. “I’m not quite sure what I’ll be doing 10 years from now, or even one year from now,” she says. “I’d love to end up teaching criminal law, but I want to practice first and experience the gritty realities of litigation.” —Mikhail Horowitz

7

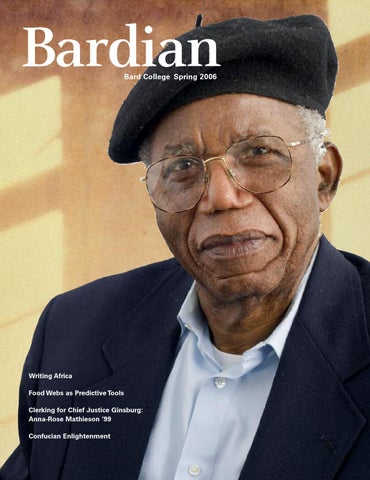

Clockwise, from left to right: Helon Habila, Emmanuel Dongala, Kofi Anyidoho, Caryl Phillips, and Chinua Achebe

8

WRITING AFRICA In Search of “A Balance of Stories” In Home and Exile, Chinua Achebe, the Charles P. Stevenson Jr. Professor of Literature and Languages at Bard, reflects on the 20th century as the beginning of “‘re-storying’ peoples who had been knocked silent by the trauma of all kinds of dispossession,” and expresses his hope that the 21st century will see a “balance of stories.” Achebe played a seminal role in creating a tradition for “writing Africa,” and Kofi Anyidoho, Emmanuel Dongala, Helon Habila, and Caryl Phillips are building on that tradition. The five distinguished writers and educators came together at the College last October to discuss the history of fellowship and conflict between African and African diaspora writers and to address the impact of such issues as pan-Africanism, colonialism, and postcolonialism on their work. Jesse Shipley, director of the Africana Studies Program, moderated the event, which inaugurated the Chinua Achebe Fellowship in Global African Studies at Bard College and was cosponsored by Barnard College’s Literature of the Middle Passage course. Chinua Achebe has taught at Bard since 1990. Originally from Nigeria, the poet, novelist, cultural critic, and essayist is perhaps best known for his 1958 novel Things Fall Apart, considered by many the premier work of African literature. In September 2005, he was named one of the world’s top 100 public intellectuals by Foreign Policy magazine. Helon Habila, also from Nigeria, is the first Chinua Achebe Fellow at Bard. His debut novel, Waiting for an Angel, was published in 2003 and received a Commonwealth Writers Prize. Kofi Anyidoho is a poet, critic, and professor of literature at the University of Ghana, his alma mater. His most recent collection of poetry is PraiseSong for the Land. Emmanuel Dongala, a novelist originally from the Congo Republic, teaches Francophone African literature at the College and is the Richard B. Fisher Chair in Natural Sciences and professor of chemistry at Simon’s Rock College of Bard. Caryl Phillips, a native of St. Kitts who was brought up in Leeds, England, is the author of three books of nonfiction and eight novels, including Dancing in the Dark (2005)

and Crossing the River, which was shortlisted for the 1993 Booker Prize for Fiction. He is a professor of English at Yale University and last fall was a visiting professor at Barnard College. Excerpts of the panelists’ remarks follow.

CARYL PHILLIPS In the 1930s, in Paris, two remarkable men sat down for a series of conversations. One was Léopold Sédar Senghor, a student from Senegal, and the other Aimé Césaire, from Martinique. The young men saw themselves as artists, but they also felt that they had a responsibility to shape the political direction of their respective countries once they had completed their studies. Senghor would eventually return to Senegal and become its president, and Césaire returned to Martinique and became mayor of its capital city. Beyond their obvious like and trust for each other, what bound these men together was their conviction that colonialism was most vigorous and corrosive when it sought, as it inevitably did, to destroy something they understood to be black culture. Neither man could conceive a future for himself in which his efforts achieved validation only when reflected through European eyes. Their philosophy—for after all they were French—came to be known as “Negritude.” It was a

9

mode of thinking that suggested that a common black culture existed, a culture whose strengths were such that if one could only recognize and promote them, it would no longer be necessary to continually negotiate Europe’s assumption of black inferiority, artistic or otherwise. In September 1956, both men once again found themselves in Paris for the Conference of Negro African Writers and Artists. It soon became clear that those in attendance were continuing the same conversation that Senghor and Césaire had begun two decades earlier. In the intervening years, the conversation had become a movement, and most of those at the conference took it for granted that all black people possessed a common heritage that existed in opposition to Europe. James Baldwin, who wrote about the conference, felt that there were three clearly expressed aims: to define or assign responsibility for the state of black culture, to assess the state of black culture at the present time, and to open a new dialogue with Europe. But Baldwin detected something else: a discomfort between what he termed the American Negro and other men of color. Potentially, an African man and a Caribbean man have much in common, largely because they were forged in the same crucible of colonial exploitation. But the African American has an altogether different history. He has not been shaped by colonialism, but by American expansionism. In fact, he’s been a central participant in it. Remember, the buffalo soldiers had rifles. Along with Baldwin, Richard Wright was in the audience. Although these two writers hardly agreed on anything else, they were agreed on the central divide between American Negroes and these colonials. Both Baldwin and Wright felt that, despite their checkered relationship with the United States, they had been born into, as Baldwin put it, “a world with a great number of possibilities.” Baldwin felt strongly that it was part of his struggle as a writer to encourage Negro Americans to see themselves as Americans, and until they could do that, they had no place at all thinking of themselves as Africans. Today, 50 years after the conference, we still have major migration from Africa and the Caribbean to Paris and London and the United States, now clearly the first choice of most migrants. There’s an economic pull that draws people to the United States, but there is also the hope of being able to function in a society that does not view people of African origin through a reductive colonial lens. In this sense, Negritude has been replaced by “migratude.” But let me conclude by returning to the problem that daunted the conference in 1956 and continues to cloud the 10

conversation today. How does one have a conversation between African writers and writers of the African diaspora and productively include African Americans? And if we do speak, what should we talk about beyond banalities of pigmentation? The question, perhaps, will not be so much about finding a common black culture; it will be a question that brings us back to colonialism: the quest for power. How does power operate on the social, political, and artistic expression of a people? A consensus on the word “power” might be a good place to begin. Baldwin, always intuitive, already knew this: he entitled his essay on the conference “Princes and Power.”

EMMANUEL DONGALA I would like to talk briefly about the problem of identity confronted by Francophone African writers. It seems that this problem of identity, the so-called authentic African identity, has been more of an issue in that part of Africa writing in French. The reason may be that Francophone African literature began not in Africa, but in Paris. In Anglophone countries it started on the continent. Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, for example, were written in Africa, in Nigeria. Read Things Fall Apart, and there’s no doubt in your mind that the writer knows intimately the culture he’s talking about—it is his culture. Francophone African literature started from the banks of the Seine. It tried to include all of the diaspora, le monde negre, from Africa to America to the Caribbean. When you have such an inclusive movement, you refer more to imagined entities than to real ones; you deal more with generalities and, inevitably, ideologies. And when you try to deal with a specific culture, it’s a culture remembered, re-created. In his book L’Enfant Noire, Camara Laye deals with the Malinke culture in Guinea. It’s a culture remembered from Paris, a celebration of a mythical and paradisiacal Africa. I don’t know whether this quote is true, but Chinua was

quoted as saying that he found that book “too sweet” for his tastes. Negritude, this sort of celebration of Africa, was in part a reaction to the belief that colonialism had destroyed and offended African culture and identity. The remedy was thought to be simple. It was through anticolonial struggle. It was as if African identity lay somewhere in the path, and to fetch it, to redeem it, all one had to do was remove the cultural and political obstacles preventing you from reaching it. Well, it turned out that was not true. After independence, not only was the so-called authentic African identity nowhere to be found, but the problem was more complex: writers were confronted with a moving identity. In any case, has there ever been such a thing as an authentic African identity in a continent with so many ethnicities, each with their own individual culture? You read Things Fall Apart and learn that in Ebo traditional society, twins are evil and have to be abandoned to the forest to die. Read my own Little Boys Come from the Stars and you will learn that twins are to be celebrated and that their mother is given a special status. How can a writer in postcolonial Africa talk about a supposedly authentic African identity when it can be, at the same time, Christian and Muslim, animist and Marxist? And what is his or her identity when he or she is a son or daughter of immigration? Are you still an African writer when you have not lived on the continent at all and do not speak any African languages? What is happening now is that the Francophone writer does not pretend to speak for the people anymore. He has learned modesty. Like most writers, he or she is now more concerned about his own vision of the world than anything. Many of them do not want to be called écrivain engagé, the committed writer, anymore. They do not even want to be called an African writer. Just writer. So the problem of identity faced by the first generation of Negritude writers has not been resolved by the younger generation; it is just reappearing under a new guise.

young Africans who do not see their future in Africa. My students are busy spending the time they should be spending on reading their books, preparing for their exams, or thinking of a future for themselves where they are, in planning an exit. At my university, most in the last class of medical doctors were not at the graduation ceremony to receive diplomas; they had already left, most on their way to America. What would it take for us to reinvent a future for our young people at home? It is important to keep reminding ourselves of stories like those Neto has left us, stories about how once upon a time we had our world in our hands and stories about how we lost that world. And above all, stories about how we can get back our own world. Some tell us that our salvation lies in the refutation of our history of pain, our history of shame, our history of endless fragmentation. But we must wander through history into myth and memory seeking lost landmarks in a geography of scars and fermented remembrances. It must not be that the rest of the world came upon us, picked us up, used us to clean up their mess, then dropped us off into trash, hoping that we remain forever lost among the shadows of our own doubt. Ours is a quest for a future aligned with the energy of recovered vision. With so much left undone, to keep calling our situation a dilemma is just an excuse for inaction. We must recall that we are the people who once wrote it down with civilization’s life still blowing through our minds. For 500 years and more we have journeyed from Africa through the Virgin Islands into Santo Domingo, from Havana in Cuba to Savannah in Georgia, from Ghana to Guyana, from the shantytowns of Johannesburg to the favelas in Rio de Janeiro. And all we find are a dispossessed and battered people still kneeling in a sea of blood, lying in the path of hurricanes. But no matter how far away we try to hide away from ourselves, we will have to come back home and find out where and how and why we lost the light in our eyes, how and why we

KOFI ANYIDOHO “My hands lay stones upon the foundations of the world. I deserve my piece of bread.” These are the words of the late Agostinho Neto, poet, freedom fighter, president of Angola. In a world in which Africa has taken on the image of poverty, of the professional beggar, we have to come back to the understanding that it has not always been like that. In fact, once upon a time, the world came to Africa to learn. Today we in Africa ourselves are finding it very difficult to believe that’s true. We are faced with a generation of 11

have become eternal orphans. We must remind ourselves that just to survive, barely to survive, and merely to survive can never be enough. HELON HABILA It has occurred to me that most of the novels by the new generation of African writers seem to be concerned with coming-of-age themes. This emerging generation of writers has been described as witnesses to the challenges of living in a society in transition, as both the victims and chroniclers of a prolonged season of pain. In Moses Isegawa’s Abyssinian Chronicles we come face to face with the civil wars in Uganda. In Chris Abani’s GraceLand we see the chaos that was Nigeria under the long stretch of military dictatorships. Diane Awerbuck’s Gardening at Night tells of a young lady’s coming-of-age confusions and desires for South Africa. From the same country we have the late Phaswane Mpe’s Welcome to Our Hillbrow, with its treatment of black-on-black xenophobia and the ravages of AIDS on the people of Johannesburg. Despite the diversity of subjects treated, these young writers are all trying to make sense of the world around them. In choosing the bildungsroman form, it is as if they are crying out, “We are just beginning. We know you look to us for answers and interpretations, but we are as helpless as you are.” I cannot help but compare this generation to the first generation of African writers whose reign began with the publication of such landmarks as Things Fall Apart, A Grain of Wheat, and The African Child in the 1950s and 1960s. This was a time when Africa was reeling under the shackles of colonialism, when books like Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and even the adventures of Tarzan were the standards by which Africans were judged. The pan-African politicians and poets tried to correct this astigmatic perception of the African, but without much success. After them, the

12

Negritude poets tried the same thing. Critic Simon Gikandi suggests that these writers were so focused on countering Western imaginings, that they forgot the essential point at stake: the invention of an African culture independent of Europe. So it was the first generation of writers, and Chinua Achebe in particular, who were able, at that moment of transition, to supply African and even non-African people with an African culture they could read about, discuss in class, and write papers on. The kind of society that the new African writers, the third generation writers, must make sense of is a society that still struggles between democracy and dictatorship, a society where most of the graduates are unemployed because of the collusion between the unfair global economic system and corrupt politicians, a society where most of the women are still exploited and voiceless. And I see in the works of these young writers a feeling of exhaustion, a lack of conviction about the ability of the societies represented to triumph over the obstacles in their path. I think my generation seems to lack conviction not because it has forgotten its history, but because it’s not sure of the efficacy of literature to repeat the kind of feat that Professor Achebe achieved. Notice that I’m taking it for granted that one of the most important duties of a writer is to act as his community’s conscience. But we are talking about a society where all accepted avenues for protest and dissent have crumbled. In Africa, we now have more newspapers than we had before, more writers, but because of the desensitization of the societies no one pays attention to the written word. It seems that to protest, to express dissent, one must resort to extraliterary channels. And so recently, to make himself quite clear to the Nigerian government, Professor Achebe had to turn down an award. And two weeks ago, the 71-year-old Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka had to take to the streets to demonstrate against the government’s economic policies. This desensitization to literature is not is unique to Africa. Writers now are in competition with the fact-churning industries—the search engines, live television broadcasts, DVDs. And when people do talk about books it is not about whether they are good or bad, but about what prizes they have won or how photogenic the author is. I hate to conclude on this pessimistic note, so I will borrow a few hopeful words from a recent essay by Salman Rushdie: “Not even the author of a book can know exactly what effect his book will have, but good books do have effects, and some of these effects are powerful, and all of them, thank goodness, are impossible to predict in advance.”

CHINUA ACHEBE Not long ago, I watched a program in which a group of upper-middle-class white women were discussing the flood in Louisiana. In particular, they were discussing the fact that a disproportionate number of black people were those who appeared in the pictures, who were having the worst of it. And one of the women asked why it was that, whether in Louisiana, or in Haiti, or in Africa itself, poverty seems somehow to attach to blackness. Somebody said it was not a question of race, but a question of class, which is the best position we have invented to save us from the awkwardness of this question. But it’s a question that has occurred to many of us. It’s occurred, for instance, to the African American historian Chancellor Williams. I once was in his audience, and he was asking the same question. As a child growing up, he said, he wondered why black people were always at the end of the queue. He knew he wasn’t more dumb than other people; in fact, he beat everyone in his class. So why was it that at the end of the day he was at the end of the queue? Now this question has a very simple answer. The answer is that these black people, whether you see them in Louisiana or in Haiti or in Africa itself, have the same story: the story of the slave trade. What happened, happened first in Africa. The consequences then spread throughout the world. We writers have to do the homework to find out the history of what happened to us. In my third novel, Arrow of God, I wrote in a character from real life. My parents were Christian evangelists and they knew the early missionaries who brought the gospel to my part of the world. And they spoke about a Mr. Blackett, who was so learned, they said, that he was more learned than white people. Blackett came from the West Indies with an Anglican mission. He was the director of education and he became a legend, a man everybody was talking about. This went on under the British, who owned the colony of Nigeria and who, for reasons of their own, decided that they didn’t

need the word of God anymore and sent Blackett home. So I put this man in my novel as a legend. He didn’t do very much, but he lived in my mind and was part of it, so I put him in. Now, 10 years later, I get a letter from a headmaster in the Caribbean. He says, “I just read your novel, Arrow of God. Thank you very much for the tribute you paid my late father.” The letter went on to explain that this was Blackett’s son, who, as it happened, was born in Nigeria. My mother, who was 80, remembered this little boy. The Caribbean missionaries clearly understood that there was something binding them to the Ebo people in Nigeria. The experience of black people in the United States is different from the experience of black people in the Caribbean. It is different from the experience of black people in Africa. But that doesn’t cancel the fact that this is basically the same story. The first and only time I met James Baldwin was in Gainsville, Florida. The African Literature Association had invited him and me to hold a conversation. I was very excited. Six years before I had come to this country for the first time on a fellowship given by UNESCO. I’d discovered Baldwin, and he was one of the reasons for choosing to come here. I came in ’62, I believe, and I was told that Baldwin was in France and wasn’t likely to be back. So I didn’t see him. Then this opportunity came at the conference. I was so excited that when I met him I wanted to say, “Mr. Baldwin, I presume.” Well, I didn’t, but later I talked to him about it, and Baldwin laughed so much, you could see his eyes jumping. When he had the opportunity to speak, he turned to me and said, “This is a brother I have not seen in 400 years.” The audience exploded. They were so loud they nearly missed the next thing he said, which was, “It was never intended that he and I should ever meet.” Baldwin had his difficulties with Africa, and he said so quite openly. But he was wrestling with it, because having difficulties with Africa doesn’t mean saying “I didn’t come from there” or “I came from there and I didn’t like it.” It is important for us to understand that when we see black people at the end of the queue in Haiti, in Louisiana, in Nigeria, it’s because they have the same story. And it is the business of the writer to deal with this story and all its ramifications. It’s extremely complex, but we must never surrender to despair. I don’t think that will do at all. We’ve got this task, this job, to write Africa. And it’s extremely important to understand and appreciate that it’s going to take a long, long time.

13

NOT BY ROTE Carole Ann Moench and Kate Belin, Members of the MAT Program’s First Graduating Class, Make Marks in the Inner City

Words are scattered across a seventh-grade classroom board: “sound”; “ groaned”; “fawn.” At tables around the room, students sort through envelopes stuffed with words that their teacher has asked them to arrange into a poem. Outside, an autumn sun shines on high-rises covered with graffiti, interrupted by rows of new, single-family row houses, many with cars parked on tiny concrete aprons in front. Barely 10 years ago, the East Tremont section of the South Bronx still looked as it did in the famous photograph of President Jimmy Carter touring the rubble-strewn neighborhood. Today, the row houses are gaining ground, but the area remains one of the nation’s poorest. Many students at Fannie Lou Hamer Middle School and High School come from East Tremont or other parts of the South Bronx. “The parents come in and say, ‘I teach my kids to fight because that’s what they have to do to survive,’” says Carole Ann Moench, the teacher giving the poetry lesson. Moench, who teaches humanities at Fannie Lou Hamer Middle School, and Kate Belin, who teaches math at Fannie Lou Hamer High School around the corner, both graduated last year from Bard’s new Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) program. The MAT degree blends advanced work in a grad-

14

uate student’s chosen discipline—for Moench, literature; for Belin, math—with teacher training, including practice teaching in public school classrooms, and certification over the course of a full year. “We believe good teaching should grow out of the practice of the academic discipline being taught,” says MAT program director Ric Campbell. “One error in public schools is that we tend to infantilize learners, to see sixth graders and ninth graders as capable of far less than they are. Typically in schools, we march kids through a fixed curriculum dictated from above, rather than letting a teacher’s deep interest in his or her field determine the course of study.” In an inner city school, it might seem quixotic to try to turn humanities students with reading problems into poets, or 11th graders struggling with division into mathematicians, but both MAT teachers feel their Bard training has been a plus. “It’s hard to learn if you’re just told to memorize facts,” says Belin. “These kids haven’t been able to explore on the way; it’s not that they’re not capable of it.” In that spirit, Belin asked a recent class of 11th graders to prove that the same rules apply to polynomials as numerals. While the students traded insults, magic markers, and iPods,

Belin went from table to table, answering questions and pulling out blocks to help visualize principles of length and height, multiplication and subtraction. When it came time for each table to explain what they had discovered, each group demonstrated their proofs, punctuating explanations with expletives. Belin answered some students’ protests calmly with, “We’re also working on our presentation skills.” Surface static rarely throws Belin. “The students care a lot about what they’re doing,” she says. “They take it very seriously, even when I think that they’re not. I didn’t like some of the schools in really privileged upstate New York where I student-taught. That’s what brought me to the South Bronx. Fannie Lou Hamer makes sense to me.” Now 23, she grew up in Youngstown, New York, and dreamed for years of being a public school teacher like her aunt. Belin does not gloss over the challenges of teaching a troubled population, but draws a distinction between her learning curve and theirs. “Making students do things is just hard,” she says. “I can’t tell if I don’t like it or I’m just not good at it yet. I’ll be making people do things for the rest of my teaching career.” For Moench, 29, who taught for several years in a New York City preschool, handling a classroom isn’t new, but getting the students to focus can be a battle. “I should be able to have a thick skin, but when the kids don’t respond to the lesson plan it upsets me,” she says. A Houston native, Moench found her way to Bard through a college fair. She graduated in 2000, returned for the MAT program, and ended up with a Petrie Fellowship, a cash award to a graduate who commits to teaching five years in New York City schools. “When I came to Fannie Lou Hamer, I wasn’t thinking I was going to save the world,” she says. “These kids are delicate; it’s a tough classroom environment. I knew it was going to be a daily fight to get them to like what I was teaching.”

Carole Ann Moench (center)

Fannie Lou Hamer Middle School principal Lorraine Chanon believes that the schools’ size—the high school has 450 students; the middle school 175— and staff-run structure make a Bard partnership particularly fruitful. “Bard is clearly an institution that believes in the empowerment of students,” she says. “Carole Ann is socializing kids to what it means to be a student, as well as teaching thinking skills they can carry through life. Kate’s classes are prepping students to life beyond high school, to college, to the world of work.” Campbell believes that the MAT Program, with its emphasis on teaching the discipline of a field, offers particularly good training for schools like Fannie Lou Hamer. “Carole Ann and Kate are poised to move on in their graduate work, but they’ve chosen to go into public schools with a deep commitment to their disciplines and how they look at the world,” he says. “Students often don’t have a grasp of how or why what they’ve been taught works. They just have enough practice to answer test questions correctly. It’s the teach-to-the-test phenomenon. What’s important is for them to achieve an authentic understanding.” While the MAT philosophy shapes both teachers’ approaches, they have set realistic goals for their students, and themselves. Belin finds her optimism growing. “I find myself looking forward to next year,” she says. “I think every new teacher quits four times a week their first year. I would not want to give up on anything until I knew how to do it well.” For her part, Moench is learning the limits—and possibilities—of what she can help her students achieve. “There are a lot of things that I have no control over,” she says, “but I do have control over my classroom and what goes on there. I can’t follow every kid home at night. I have little say in legislation that passes or doesn’t. But I have a classroom of 20 kids for an hour and a half each day and I can try to make that as positive a learning experience as I can, both for them and for me.” —Hanna Rubin

Kate Belin 15

LOOKING HOMEWARD

An Internship of Consequence In 2004, Reporters Without Borders ranked the Philippines second only to Iraq as the most dangerous place for a journalist to work. They reported that more than 50 Filipino journalists have been assassinated since 1986, the year that nation ousted Ferdinand Marcos and returned to democratic government. Jomar Giner ’07 knows these facts well. The political persecution of journalists, human rights advocates, and political opposition leaders in the Philippines was the focus of her internship at Human Rights Watch (HRW) in fall of 2005. When she opted to intern at Human Rights Watch, as a student in the Bard Globalization and International Affairs (BGIA) Program in New York City, Giner had little idea how vital her work would be. She was initially attracted to HRW because of the group’s film festival, as she’d worked for two summers at Amnesty International’s similar festival.

“I thought that would make an interesting comparison,” she says. “Then I saw that HRW was looking for an intern in its Asia division and that the associate overseeing the internship was Bard alumna Jo-Anne Prud’homme ’04, who also went to BGIA and interned at Human Rights Watch.” Prud’homme ultimately became Giner’s on-site mentor. “When I was preparing for the interview, I learned that HRW’s Asia division was not actively covering the Philippines,” Giner says. “I was born in the Philippines, lived there for 11 years, and am a native speaker of Tagalog, so I was naturally interested in issues there. I also knew that there were a lot of human rights violations, and I was surprised that they weren’t mentioned on the HRW website. I found out that HRW didn’t have the resources to cover the Philippines at that time, and they wanted an intern who could document the situation there.”

16

Filipino detainees are hosed down after police storm their cells inside the prison camp in Manila’s Police Camp Bagong Diwa. Jomar Giner ’07

Giner’s language skills, academic goals, and growing personal interest in the research made the internship a perfect fit. It also met her desire to do work that would matter. “Because she’d worked in a similar position, Jo-Anne understood that I wanted my work to make a difference,” Giner says, “and she continually assured me that the research would be used.” As soon as she arrived at HRW, Giner began gathering reports and data on specific instances of politically motivated murders, abductions, and torture. The process involved online research, reading Philippine media, and talking with human rights advocates working there. “One good thing is that many of these instances are documented in the media, because Philippine civil society is very strong, even though the press is facing a lot of repression,” Giner says. “I decided to research beginning in 2001 when the current president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, started her term. At first I recorded violations across the board, against women, children, indigenous people, and political activists, but soon I decided to concentrate on political assassinations, which I felt were the most pressing.” One of Giner’s first realizations was that, although the United States’ “War on Terror” provides support intended to crack down on Islamic terrorists based in the Philippines, the resulting practice is overall repression of not just the Islamic separatist movement, known to use terrorist tactics, but of all Philippine Muslim populations, communists and former communist associates, and members of any leftist political groups. Giner’s research began to hit closer to home. “There were points when I became very emotionally involved,” she says. “I really loved my life there, and I still have friends there and family members. Also, my parents have ties to these victimized groups. My mother used to be a journalist in the Philippines, and her former editor now serves in the Congress for a minority party-list group.” Party-list groups are the political voice of marginalized sectors and are guaranteed 20 percent of Lower House (House of Representative) seats, a per-

centage that suffers under corrupt election processes. They are often accused of having ties to the communist insurgents. Giner says that while that may have been true in the past, these political minorities are trying to address their concerns through legal means using the political process. “Many of the victims are people my age doing what I’m doing,” says Giner. “They’re activists doing legal things to voice their concerns, but they’re being targeted. I could easily have been among them if I hadn’t come to the United States. At the end of my research, I had documented over 140 incidents of serious violations since 2001. Many are murders and abductions that took place in broad daylight, committed by masked gunmen on motorcycles. The assailants are often military personnel in civilian clothing, and people know that openly.” By October 2005, Giner had completed a major research report that, she has been told, will be used as the basis for a fact-finding mission to Mindanao, perhaps in summer of 2006. Following that initial report, Giner began to look into abuses of political detainees. She also continued research on the approximately 140 political assassination she’d recorded, assured that future efforts by HRW would put her work directly to use. As a BGIA student, Giner combined her internship with academic work at BGIA, spending approximately 25 hours a week at Human Rights Watch and participating in seminars and study at BGIA in New York City. Giner’s internship work led to her successful application for a $2,500 grant through Bard’s Freeman Undergraduate Asian Studies Initiative, supported by the Freeman Foundation. Giner will use the grant to travel to the Philippines in summer of 2006 to research the “people power” movement and the role it has played in Philippine national elections since 1986. “The people power movement began in 1986, and the current president, Arroyo, got her seat with the movement’s support, which took out the previous president,” Giner says. “Arroyo is now under criticism for election fraud and related corruption charges, so the process hasn’t worked out the way many thought it would. Some would say it’s even worse now.” She is planning to look at how different segments of the population have participated in the movement. Giner is looking forward to her return, albeit brief, to the Philippines, to renew contacts with friends and family, meet face-to-face those whose work informed her research, and investigate firsthand the flawed, complex political system she’s been studying at Bard. —Lucy Hayden 17

The Golden Rule’s Contemporary Relevance Scholar Introduces First-Year Students to Confucius If a man withdraws his mind from the love of beauty, and applies it as sincerely to the love of the virtuous; if, in serving his parents, he can exert his utmost strength; if, in his intercourse with his friends, his words are sincere—although men say that he has not learned, I will certainly say that he has. —Confucius (551–479 ...), The Confucian Analects, Book 1:7

18

The ethical tradition known as Confucianism began 2,500 years ago with the teachings of a man called K’ung-fu-tzu, a native of what is now China’s eastern Shandong Province. K’ung-fu-tzu (also called Kongfuzi and Kongzi) spent much of the early 500s and late 400s as a traveling scholar and adviser to political leaders throughout China. The philosophical system he developed and preached became a pillar of traditional Chinese culture and eventually spread across the world. In the west K’ung-fu-tzu is known as Confucius, a popularization of his Chinese name adopted by Jesuit missionaries in the 16th century, and his teachings are collectively known as Confucianism. Adherents of Confucianism believe that the individual is the key element of all human relations—families, societies, and states. If the individual concentrates on cultivating personal virtues such as honesty, love, and devotion to family, the resulting harmony benefits everyone. The keynote of Confucianism is best expressed by the Confucian “Golden Rule”: “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself.” Chinese philosophy scholar Stephen C. Angle opened this year’s series of First-Year Seminar public lectures at the Sosnoff Theater of the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts with a talk titled “Confucian Enlightenment.” At Wesleyan University, where he is an associate professor of philosophy, Angle chairs the East Asian Studies Program and directs the Mansfield Freedom Center for East Asian Studies. He holds a B.A. from Yale University and a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. As he explained to his audience at the Fisher Center, Angle’s view is that “Confucianism is a live, ongoing source of creative reflection. One of the fundamental ways one learns to look at others compassionately—to look with just and loving attention, if you like—is to think about oneself. The key is to realize other people are like you in most respects, even though the details are different. I think it’s very natural that Confucius’s initial followers hit upon the notion of ‘sympathetic understanding’ as one way of articulating the good in ourselves, this process of just and loving attention. When you love another person, you identify with them.” With his current project, a book titled Sagehood: The Contemporary Ethical Significance of Neo-Confucianism, Angle’s goal is to articulate a contemporary philosophy that is informed and influenced by Confucian ethics. In a follow-up conversation after his lecture at the Fisher Center, he said he believes that “rich rewards await us if we look at Confucianism as a

live philosophical tradition rather than only as an object of historical study.” The title of Angle’s book requires some explanation for Confucian neophytes. “Sagehood” refers to adherents’ ultimate goal: moral perfection. Neo-Confucianism came about during the 11th century when a group of Confucian scholars, reacting to the spiritual challenges posed by the rise of Daoism and Buddhism, came together to create an updated version of Confucianism that was popular until the end of the imperial era. In response to a student’s question about the differences between neo- and classical Confucians, Angle explained, “Texts from the classical era [pre–221 ] remained touchstones for the neo-Confucians. But they interpreted the canon creatively, so it spoke to the concerns of their age. This open-minded approach to traditional Confucianism has been continued by Chinese philosophers in the 20th century, and I seek to carry on this legacy. “Topics of philosophical ethics can seem remote from our everyday lives,” he continued. “They seem to have relevance only for major decisions about right and wrong, without attending either to what might motivate us to act well, or what it means to be a good person. Many philosophers have looked back to the Greek and Christian traditions for inspiration in their critique of mainstream approaches to ethics, given the paucity of these discussions elsewhere. But, in fact, there are rich resources in the Confucian tradition as well.” In his book Angle hopes to demonstrate that the tenets of Confucianism—virtue, family, and sincerity—have a great deal to offer to the contemporary philosophical conversation about how we should live our lives. The result could be a 21st century in which we pay more attention to good behavior and less to vanity; choose to spend more time with our families and less at work; and value altruism over celebrity and power. On the surface, the Golden Rule might seem trite and simplistic. Applied to everyday situations, however, its broader applications become clearer. Give to those who are less fortunate. Respect and value all members of your family. Listen and respond to others with the same care and thought you’d expect from them. The result could be happier families and neighborhoods, political campaigns that focus on important civic matters rather than scandals, and a global conversation about cultural differences rather than fear, terrorism, and warmongering. —Kelly Spencer

19

FOOD WEBS OF THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE From Static Community Description to Predictive Tool by Daniel Reuman

From Darwin’s observations about simple food chains to today’s more complex predation matrices, the study of food webs is evolving to the point where scientists may soon be able to predict and manipulate the effects of ecological disturbances such as global warming and species extinction. Daniel Reuman, a research associate in the Population Laboratory at The Rockefeller University, visited the College in October to talk about the history and potential of food web research as part of the Frontiers in Science Lecture Series.

The concept of food webs goes back to Charles Darwin and his voyage on the Beagle. One of the first places he stopped was St. Paul’s Rocks, off the coast of Brazil. In narrative form, Darwin noted the species he found there and what

“Corresponding to average external conditions” means that you’re not going to find polar bears in Brazil. “Subject to reciprocal influences” says that each of these species interacts with each other, which is illustrated by the arrows in the directed graph. The fourth part says that you can’t take any old collection of species, toss them into a tank, and call it an ecological community—unless they persist. The directed graph is one type of mathematical encapsulation of a food web. Another is the predation matrix, which was introduced in the late 1800s. In a predation matrix, you first list all of the species in your system. Let’s say you have salmon, anchovies, zooplankton (floating or weakly swimming animals), and phytoplankton (microscopic plants). You then make a four-by-four table, put the name of each species on

“Ecological research will become increasingly driven by the desire to predict outcomes and manipulate systems. The reason is that humans are taking over more and more of the Earth, and they’re placing greater demands on ecosystems. It will have to happen so that we can learn how to protect our resources.”

each species ate. His account is descriptive, but it can be reformatted and mathematically analyzed using a directed graph. In this graph, nodes represent each species and arrows indicate the flow from prey to predator. For example, one arrow might indicate that the spider eats the fly. This is an object you can analyze. If you had several of these objects from different ecosystems, you could compare them using math and statistics. Darwin recognized that his system was reasonably isolated, but he didn’t note the importance of that fact. That took another 30 years or so. In 1887, German ecologist Karl Mobius first defined the concept of an ecological community as “a group of living beings of which the numbers and types of species and individuals correspond to the average external conditions, which are subject to reciprocal influences and which maintain themselves permanently in a specified area by reproduction.” Let’s break that down. The “number and types of species” is the same as the nodes in a food web.

each column and row, and put a “1” wherever one organism eats another. So a 1 might indicate that salmon eat anchovies and another 1 indicates that salmon eat salmon. In a quantitative predation matrix, you also list the amount that gets eaten. For instance, in my fictitious system, you note that salmon eat .01 kilograms per day of salmon and 5 kilograms of anchovies; anchovies eat a lot of zooplankton and very little of their own kind, and zooplankton eat lots of phytoplankton. As a rule of thumb, when an organism eats, it converts one-tenth of the mass that it eats into its own body mass or its own reproduction. So, if zooplankton eat 660 kilograms per day of phytoplankton, roughly 10 percent of that is eaten by anchovies, and so on. To this point, the food webs described have been static snapshots. Darwin didn’t stick around St. Paul’s Rocks to find out whether one bird species is more abundant at a certain time of year. And that brings us to the dynamics of food webs, how species populations fluctuate over time in an interrelated 21

Daniel Reuman

way. This kind of analysis requires additional data. We’ve talked about whether a species is present or not in a food web, but not about its abundance. And unless you have that data, you can’t talk about how abundance changes over time. In the 1920s, Alfred Lotka and Vito Volterra wrote equations for the dynamics of food webs. The best way to illustrate

The hare population crashes. And then the lynx population starts to crash, because the hare are becoming less abundant. Once the lynx population crashes, the predation pressure on the hare clears up and the hare thrive. This cycle repeats every nine to 10 years. The Lotka-Volterra equations model this; they predict how it works. There are some problems with the equations, primarily because things are rarely as simple as this example. But Darwin said mathematics endows one with something like a sixth sense, and now that we have a mathematical formalism for talking about food webs, maybe we can make use of that sixth sense. We want to look for structural features that are common to all or many food webs. It turns out that the proportions of top species (no predators), intermediate species (predators and prey), and basal species (no prey) in a food web are, on average, independent of the number of species. If you look at a food web with many species, it has some proportion of top predators. And if you look at a food web with a few species, it has about the same proportion. This is important. Consider that the world’s oceans are being fished at an alarming rate. Typically, the species of fish captured for human consumption are top predators such as salmon and tuna. If we reduce the number of organisms—and potentially even the number of species—at

“Darwin said mathematics endows one with something like a sixth sense. Now that we have a mathmatical formalism for talking about food webs, we need to make use of that sixth sense.”

these equations is with the famous example of the Canadian lynx and the snowshoe hare. In this simple real food web, the hare eat the plants and the lynx eat the hare. The Hudson Bay Company, which sold the furs of these animals, kept track of how many of each were trapped over a 100-year period. If you make a graph with the years on the X-axis and the abundance of hare and lynx on the Y-axis, you learn a number of interesting things. About 1862, the populations of both lynx and hare are low. Then the hare population goes high really fast. Soon the lynx population starts to rise. Then, once the lynx population gets pretty high, the hare population starts to drop. It’s because the burgeoning lynx population is eating them all. 22

the top of the ocean food web, it might lead to consequences where the whole web is modified to bring the proportion back into play. One way might be through the extinctions of smaller organisms. It also turns out that the number of trophic links (links away from the base food producer) is proportional to the number of species. A big food web has a certain number of predator-predator relationships. A smaller web has a smaller number, and the relationship is linear. You can predict, based on the number of species, approximately how many predator-prey interactions there are going to be in a community.

Scientists want to understand how interacting populations in a food web change over time in order to understand the effects of such ecological disturbances as species invasion or global warming. If you add a new species to the system, what’s going to happen? If you’ve got a lake where a fish dies off for some reason, what are the cascading effects? There are about 50,000 non-native species in the United States, and the cost of managing these invasive species is estimated at $137 billion per year. How do we predict what will invade successfully? How do we control invaders more easily? To date, much of the work done with food web dynamics has been theoretical. However, several recent improvements are going to help bring dynamics closer to reality, in my opinion. The abundance web is one. There is also a food web that includes average population density and average body mass of each species. If you know the distribution of body masses for each species, then you have a chance of modeling that a particular species will switch prey as it gets bigger. The addition of stoichiometric data might also make food web dynamics more plausible. Every organism has a

characteristic ratio of carbon to nitrogen to phosphorus. It turns out that vertebrates have more phosphorus than invertebrates. I’m a vertebrate, so it may be that I seek out items with more phosphorus, in order to build my skeleton. I also think qualitative prediction will become possible in more complex cases than the lynx and hare, and that we will soon be able to say, “the population of this species will go down” or “this ecosystem will become more fragile if we do x, y, and z to it.” As humans take over more and more of the Earth, they’re placing greater demands on ecosystems, and I think research will become increasingly driven by the desire to predict outcomes and manipulate systems. We need to protect our resources. Daniel Reuman holds Ph.D. and M.S. degrees in mathematics from the University of Chicago and a B.A. from Harvard University. His research interests include applications of mathematics to ecology, epidemiology, and social policy analysis. He has taught at the University of Chicago and Harvard.

23

NOT “EASY LISTENING” Mercedes Dujunco Raises Dissonant Issues About World Music “These are the days of miracle and wonder,” sang Paul Simon on Graceland, a 1986 album that introduced Western listeners to Ladysmith Black Mambazo, an ensemble of Zulu singers. Not least of those miracles and wonders is the fact that, for better or worse, the increased accessibility of sophisticated recording technology and the ineluctable pull of the global market have resulted in “world music,” the widespread dissemination of formerly localized or restricted musical fare. Even a quick skim of the listings for concert halls and clubs in any cosmopolitan city will reveal performances of Tuvan 24

throat singing, Balinese gamelan, Cuban son, and Japanese Kodo drumming, as well as curious hybrids of every imaginable stripe—Celtic klezmer, Native American jazz, Russian reggae, and even, perhaps, Hawaiian oompah. So one could assume that students taking Mercedes Dujunco’s Introduction to World Music already have a fairly good grasp of the subject, yes? “They think they do,” says Dujunco, an ethnomusicologist and an associate professor of music at Bard. “A lot of things are passed off as ‘world music’; it’s essentially a marketing term. Much of what falls under its rubric is very diluted, or exoticized, or put on stage out of context, so that it can cross over to the mainstream and be made more palatable for Western audiences. “We cannot stop this commodification and appropriation of non-Western music,” she continues. “My job is to inform students of where the music came from, in what context it was played—so that, for instance, when they get their

hands on sampling equipment, they’ll know what is ethical or not ethical to take and manipulate.” On a clear, crisp, September afternoon outside of Blum Hall, as the sweetly entwined voices of chamber singers further mingle with the raspier voices of late summer cicadas, Dujunco discusses myriad issues addressed by her introductory course, and by ethnomusicology in general. “Ethnomusicology is basically the study of music and its relationship to different aspects of culture,” she says, adding that the field can accommodate all forms of musical expression—everything from the warrior songs of the Maori to the sonatas of Mozart. “If I were to study Mozart from an ethnomusicological perspective, I would look at him in the social imagination, the perception of him and his music by a cross section of society. This would include an examination of which of his works are played, how often, in what way, and as part of what kind of events—a Mostly Mozart series, concerts in the park, or piped-in music in planes.” Such a study would proceed from the assumption that “Mozart’s music is not handed down wholesale through the ages, but selected and reinterpreted in order to resonate with presentday sensibilities.” In her world music class, however, Dujunco places the emphasis on non-Western musical styles, “because they get short-shrifted.” Born in the Philippines and trained as a classical pianist, Dujunco had her first revelation of cultural short-shrifting as an undergraduate. She took a class at the University of the Philippines with the pioneering ethnomusicologist José Maceda, and it opened her eyes, she says. “I thought, here we are, an Asian country, but we’re Americanized; I know nothing of my own traditions. It made me question the whole history of how I got to be playing Western music. . . . I began to realize that music doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it has a social and political context.” Her postgraduate studies at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music served to deepen her appreciation of non-Western musical traditions, particularly those of China, Vietnam, and the Chinese diaspora communities of Thailand. Eventually, she immersed herself in a form of Chinese string ensemble music called xian shi yue and became proficient on the zheng, a plucked board zither whose modern incarnation has 21 to 25 silk strings. Bard students have had the chance to hear and play the zheng in Dujunco’s Chinese music ensemble workshop, along with other venerable instruments such as the di (a bamboo transverse flute), erhu (a two-stringed fiddle), and the pipa (a short-necked, pear-shaped plucked lute.

Although most of these folk instruments can be traced back to antiquity—the zheng, for instance, dates to the Qin Dynasty, circa 221 ...—how they have been played, and even whether they may be played, has often been influenced by extramusical considerations and circumstances. As Dujunco noted in her Ph.D. dissertation, the Chinese government banned the playing of xian shi yue from 1949 through most of the 1970s, deeming it to be “feudal” or “counter-revolutionary.” It’s precisely this sort of context that students acquire in Dujunco’s classes, along with an increased awareness of the thorny questions involving music and identity politics, music and cultural difference, and music and its commercial exploitation. A particularly ticklish area is the secular use, by outsiders, of sacred music. Examples of such misrepresentation are depressingly plentiful. “I remember a student of mine who wanted to sample Qur’anic chant and incorporate it in her remix CD,” says Dujunco, with a wry smile. “There’s also the case of Sister Drum, an album by the Chinese composer He Xuntian, the tracks of which include a sampling of Tibetan chant. This is a particularly egregious act of cultural appropriation, given the larger context of the lopsided nature of Chinese-Tibetan ethnic relations.” The only effective way to countervail such tendencies is to educate listeners—and not merely in the classroom. “Performances should always be accompanied by symposia,” she says. “Recordings should contain detailed liner notes, such as those provided by the Smithsonian reissues. Even with museums, there’s this tendency to pick the most exotic elements of a culture and package them, so you don’t get to see the broad spectrum of what goes on.” One thing that would help, she says, would be for cultural venues to present a variety of little-known performers in addition to the same two or three “superstars” who have been designated, whether they like it or not, to represent a whole culture. Ultimately, what Dujunco seeks to impart to her students is that there’s a whole world of musical expression out there that is distinct from our own, and if we approach it respectfully, with open ears and an open mind, it will enrich us. “Music is a gateway to understanding other cultures,” she says. “I want students to be able to talk about a musical culture other than their own intelligently, on its own terms—to take into consideration how people in that culture think about their own music, rather than imposing our own values on it, and to be able to share that with the people they know. I want them to develop a very cosmopolitan tolerance for music that they may not even like, but can appreciate for its own merits.” —Mikhail Horowitz 25

SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND SOCIETY Furthering Cross-pollination among Academic Fields

What are the possible social consequences of genetic research? How do emerging technologies shape the way elections are run? How have technological advances changed the definition of human rights? These and other questions reflect our increasing concern about the interrelation of scientific and technological systems with social and political life. Addressing the conversation from an academic perspective is Bard’s new Science, Technology, and Society (STS) Program. STS provides a foundation in the fields needed to study this interdisciplinary subject in conjunction with a primary divisional program. The program allows for study in a number of areas that span the academic divisions—such as nonfiction science writing, film and electronic arts, or developmental economics and technology—and promotes scholarship that confronts the key issues raised by contemporary science and technology. Students in STS follow, in conjunction with their primary program requirements, a challenging curriculum that includes 26

one two-course sequence in a basic science (biology, chemistry, computer science, or physics) and two additional courses in the Division of Science, Mathematics, and Computing; two STS core courses, along with two more STS cross-listed courses; and one methodology course, usually in policy analysis or statistics. Starting this spring, STS offers paired science and technology courses that are linked by a common theme and anchored by an introductory science class: for example, an introductory course in epidemiology paired with a course in the history or anthropology of disease. The idea behind the paired courses, according to Gregory Moynahan, assistant professor of history and codirector of the STS Program, is “to create an immediate logic of why science is in society and society is in science. Our vision is not to reduce a subject to a very specific subfield, but rather to show all the ways in which a topic like epidemiology or biology opens out into these other issues. For example, a Biology Program course in epidemiology might pair with a course in