10 minute read

Let’s Get Physics, Y’all

ALUMNI/AE COME BACK TO CAMPUS TO TELL THEIR STORIES

Let’s Get Physics, Y’all

by James Rodewald ’82

The remarkable Physics Program alumni/ae who returned to Annandale this year to share their research interests, career paths, and Bard memories with current students and the wider community weren’t butchers, bakers, or candlestick makers. There was, however, a violinmaker, a solar energy consultant, and the inventor of a drawing-based mathematics language. They came back to campus to participate in a seminar series organized by Antonios Kontos, assistant professor of physics since 2017. Hal Haggard, also assistant professor of physics, made formalizing the speaker series one of his priorities when he came to Bard in 2014.

“Over the past few years, as more of our faculty are heavily engaged in physics research—we have a theoretical physicist, two experimentalists, and a brand new astronomer—the goals for the seminar have changed,” says Kontos. Some of those goals, he says, are to engage students with what is going on in physics beyond Bard, showcase possible career paths for physics students by inviting speakers from both inside and outside academia, provide opportunities for students to ask questions directly about careers and research, instill a sense of community for students in the program (a newly instituted ice-cream social—with ice cream made by students—is another such community-building measure), and bring people to Bard who are or could be research collaborators.

The particular focus in the 2019–20 academic year was to invite back students of Professor of Physics Matt Deady (now emeritus) before his retirement. This wasn’t mere sentimentality—though the sentiment was lovely—the speakers are all doing remarkable things. After a semester of electronics with Burt Brody (now professor emeritus of physics) in which I marveled at Brody’s ability to make complicated and abstract ideas interesting and comprehensible, I enrolled in his physics class. It was twice as compelling, but 10 times harder, and I eventually gave up and dropped the class. I never stopped being interested in the subject, however, so when seminar announcements from the Physics Program started to hit my inbox last fall, I vowed to get to as many as I could. Most were way over my head, but all were thought provoking; I left each one with my mind reeling and my awe of fellow Bardians magnified. (For a complete list of Physics Program events, visit physics.bard.edu/events.)

Trevor LaMountain ’15 is a doctoral candidate at Northwestern whose recent research is on hybrid states of light and matter. “Quantum states known as ‘exciton-polaritons,’ which exhibit properties of both light and matter, form when you put certain materials between two very closely spaced mirrors,” LaMountain explains. “I’m studying new ways to manipulate and control these kinds of quantum states using very short pulses of light. By embedding semiconductors between two mirrors, we can greatly enhance the light-matter interaction, giving rise to much more exotic effects than just absorption, as in solar cells, or emission, as with LEDs.”

In an email exchange after his talk (Controlling Hybrid States of Light and Matter in Atomically thin Semiconductors), LaMountain wrote, “I think one of Matt’s biggest attributes as a teacher at Bard was the amount of time he made available to students and the extent of his investment in us. Physics can feel intimidating, and Matt always made the time to meet with students and make it more accessible. He always knew how to solve a physics problem in three or more different ways, which is a broadly applicable strategy for approaching a lot of aspects of physics, especially experimental research in the lab (which is what I am doing now). When investigating open-ended research questions in the lab, it is really important to be aware of your choice in strategy for how you are trying to answer those questions. That way, if one approach fails, which happens more often than not in experimental work, you already have an idea for the next experiment to try. This kind of more abstract skill was definitely something that began developing for me while spending time solving textbook physics problems with Matt at Bard.”

Deady’s influence went way beyond the textbook, though. LaMountain came from what he describes as a “nonacademic family,” and had assumed that graduate school would be beyond his means. “Matt was my adviser at Bard, and he was the first person to discuss graduate school with me.” LaMountain wrote. “He told me that PhDs in physics and related fields are typically funded by the university and get a stipend. Matt is from a similar background as me, which was also really encouraging. That early advising helped me believe that graduate work was something within reach, and I am extremely grateful to him for serving as a guide to all of it.”

Professor Emeritus of Physics Matt Deady taught at Bard from 1987 until his retirement this year. Photo: Pete Mauney ’93 MFA ’00

Megan Kerins ’06 has only recently begun her pursuit of a PhD, after more than a decade in the private sector and a stint with a sustainable-energy nonprofit. “I was trying to decide between going into astronomy and cosmology or something more applied after Bard,” says Kerins. “What tipped the balance was the acknowledgment that we were in a climate crisis. I wanted to solve immediate problems with my science and math skills.” This motivated Kerins to do her Bard Senior Project on the feasibility of using the Saw Kill as a hydropower energy source for Bard, a project which is now coming to fruition thanks to a New York State grant headed up by Chief Sustainability Officer Laurie Husted. Kerins earned an MS in civil engineering from Stanford and entered the renewable-energy industry, where she was involved in engineering and program management for solar and microhydropower projects in Thailand, Burma, and Ethiopia. She later served as an energy consultant to commercial-scale projects in the U.S. and Haiti. After more than a decade of navigating the challenges of working mostly in places where the infrastructure, not to mention the culture, were not always supportive, she took a job at the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), an independent, nonpartisan nonprofit whose mission is “to transform global energy use to create a clean, prosperous, and secure low-carbon future.”

During her seminar in Hegeman, Solar Microgrid Applications for Emerging Economies, Kerins discussed some of her sustainableenergy projects as well as her work at RMI, where she led the Renewable Microgrids Program. “I really wanted to show students what’s possible,” she says. “I loved physics, but I wanted to do something more applied after I graduated.” Asked why she decided to leave RMI and apply for a PhD program in electrical engineering, she replied, “As a woman in science and an engineer, it’s easier to get taken seriously if you have credentials. And research and thinking out problems deeply are things I still crave.”

Like LaMountain, Kerins credits Deady with influencing her problem-solving skills. “Matthew taught me how to think,” she says. “He would get out all this printer paper and we’d start writing the problem out, thinking about it in a methodical way. He would put everything down on paper that would be useful—I can be scatterbrained, but I was able to adopt this more methodical way of thinking.”

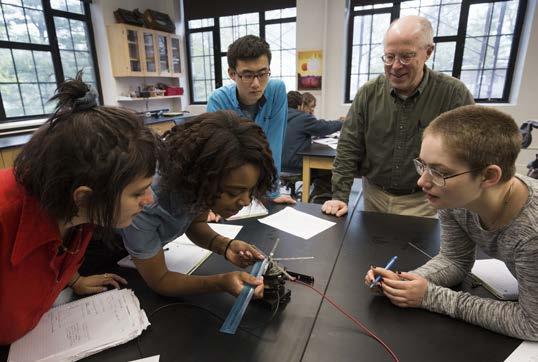

Kerins had plenty of opportunity to exercise those methodical problem-solving muscles during her time in the applied trenches, but she’ll once again be calling on some of the more theoretical aspects of physics as she pursues her doctorate. Returning to Bard brought her back to her undergraduate days. “Being in the lab and watching Matt teach reminded me why I loved physics,” says Kerins. “He makes it so fun! He loves teaching, and he really cares. He wasn’t just thinking about publishing, or raising money for his lab. At Bard it’s about teachers teaching. He really embodies the love of learning, the love of teaching.”

Rachel Spitz-Becker ’12, a maker and restorer of fine instruments in New York City, had an overflow crowd for her seminar, Perspectives on Violin Making, Restoration, and Scientific Inquiry. Deady said that in his more than 30 years of teaching acoustics a few of his students had gone on to professional careers in music, citing appropriately odd bedfellows: Grammy-nominated metal and post-rock drummer Sebastian Thomson ’94 and Spitz-Becker.

A cellist from an early age, Spitz-Becker enrolled in the Bard College Conservatory of Music and chose physics for her second degree. She took several acoustics tutorials with Deady, and for her Senior Project, “An Experimental Investigation of the Directivity of Violin Sound Radiation,” Spitz-Becker built a rig in the basement of Hegeman to hold a violin and rotate it while she took measurements of the sound being radiated. “My point was to see if the sound is actually as directional as musicians think it is. I was very proud of myself for busting the myth that the sound comes out of the f-holes. No sound really comes out of the f-holes. Of course f-holes are really important for the sound, but that was my hot ‘gotcha.’”

After earning bachelor’s degrees in cello performance and physics, she was feeling, as she describes it, “really vague” about what to do next. “I knew I didn’t want to go to a conservatory—it seemed really cutthroat—and after doing five years of undergraduate work I was not so enthused about going to get a master’s.”

Instead, Spitz-Becker applied and was accepted to a violin- making school in Salt Lake City, Utah. While she waited for the semester to start, she got a paid internship at the speaker and headphone company Bose, in the Transducer Technology Group, “where they actually design the speakers themselves—not the products, but the speakers,” she says. “It turned out to be perfect because it was basically what I’d just done for my Senior Project: taking measurements of radiated sound.”

Spitz-Becker’s captivating show-and-tell included a series of slow-motion close-up videos of violins vibrating, images of instruments in various stages of creation, parts of an actual viola, comparisons of old and new instruments, an explanation of how she makes her own varnish and pigments, and many references to the ways traditionalists view instrument making (along with occasional intimations that they might, in fact, be wrong—typical Bard student).

Nazmus Saquib ’11, whose work at first glance seems to inhabit the opposite end of the applied-versus-theoretical spectrum from Spitz-Becker, gave what turned out to be the final in-person installment of the physics speaker series for the spring semester. (The series continued via Zoom in April with Daniel Newsome ’02, visiting assistant professor of mathematics, presenting As Above, So Below, which explored “how wrong science has been in the past and how wrong it might be now” and Todd Krause ’97, physicist and linguist at the University of Texas at Austin, discussing parallels between two groups who “probe the fabric of reality” in Physicists and Papyrologists: Following the Trail of Artificers of Fact.) Saquib’s seminar, Embodied Constructionist Mathematics, took attendees through the basics of the drawing-based mathematics he invented and went on to explore some of the ways his novel and powerful drawing language leverages embodied interactions to do mathematics.

“Algebra as a tool to manipulate symbols has been widely used to deal with mathematical abstractions,” says Saquib. “In this work, I demonstrate how the embodied, constructionist, and explainable elements of basic mathematics curricula such as counting, grouping, sets, shapes, et cetera can be combined with symbolic algebra and programming concepts. Compared to symbolic abstractions, this representation is more suitable for human perception and understanding of mathematics.”

Saquib demonstrated various ways the language can be used to help everyone from children being introduced to math to scientists doing presentations, and to improve augmented reality devices. “The power of this design language is that you can turn pictures and sketches into computable and mathematical structures,” he says. “And you can define what these computable and mathematical structures will be according to the kinds of relationships you want in your pictures and sketches.”

It occurred to me as I listened to Saquib describe the use of human gestures and body postures to define programmable actions and drive interactions for storytelling, presentations, and information visualization, that perhaps I would’ve done better in physics if Burt Brody had been able to shrug, point, shimmy, and gesticulate the theories and equations. The thought alone gave me reason to smile, as do all my memories of Brody and other beloved professors, teachers who always look for ways to reach their students where they are and give them the tools to get where they want to go. The love of teaching that Matt Deady’s students all recall so fondly is part of a space-time continuum at Bard that stretches back decades and will assuredly go on long after we’re gone.

Nazmus Saquib '11 demonstrates interactive, body-driven graphics for augmented video performance in a YouTube video. From top to bottom: a slugfest, orca anatomy, sea exploration, how planes fly, semaphosic gestures, and animation