8 minute read

BACK TO BASE

from BASE # 03

The danger zone | Tom Livingstone

Photography | Tom livingstone

Advertisement

Let’s get straight to the point: climbing is dangerous. Full-blown alpinism in the Greater Ranges, meanwhile, is a dance through chaos. Mountains are inanimate spires of rock and ice, constantly tearing themselves apart, subject to natural forces of unimaginable power. Some eyes may see lines of beauty: ribbons of ice and golden granite. Others may see fear: commitment and casting far away from safety. I’m drawn to alpine climbing by a strange cocktail of both beauty and fear. Risk is inherent from the moment you step off the ground, but when clipping bolts at the local sport crag, you limit the number of dangerous variables. Bolts make climbing relatively safe. It’s okay to fall, and warm clothing and coffee keep the atmosphere suitably relaxed. When alpine climbing, you quickly realise you hold no control over the high mountain environment. Rocks fall, storms break, and seracs collapse. The consequences when something goes wrong can be far more serious than when you’re close to civilisation. Remote regions such as Pakistan’s Hindu Raj range, where I climbed last summer, are a very long way from a hospital.

Considering the major risks and their potentially very serious consequences, why look to the mountains at all? It’s a matter of perspective. One person’s gripping, disco-legging, fingersclawing pitch is another’s scramble. The thought of isolation during an expedition might make some people tense and nervous. Personally, I quite like being ‘away from it all.’ Attitude is important, and it shapes our perspective. Do you explore the edges of the map, or do you stay safe at home? Do you fear the consequences of what might be, or revel in the possibilities? Competent alpine climbing must also be about mitigating the risks. We don’t climb under seracs [ice cliffs]. We wait for settled weather. Perhaps, if we go into the mountains enough, the odds aren’t stacked in our favour, but there are plenty of old climbers who’ve struck the right balance and are still going strong. Through experience, we develop good judgement. Can you abseil off one piece of gear? (Probably not, unless it’s a tree, and they don’t grow above 5200m). Can you trust ice that goes thunk when you hit it? What sound does the wind make when it rips over a ridge in a Patagonian storm? With this judgement, we know which risks are uncontrollable, like a storm rolling in. Then we can accept and reduce the likelihood of the risks; check regular weather updates, take proper clothing, and know how - and when - to bail.

I’m partly drawn to climbing because of the risk. I wouldn’t be so interested if I fell off and simply floated to the ground. Alpinism forces me to meet my fears head on. I know I’m attracted to this internal dialogue, which often takes place as I climb another move higher above my gear. What would an MRI brain scan show? Is this when I’m most alive? Or at my most foolish?

There’s also an argument that something like alpinism is the perfect antidote to our ‘cotton wool’ society, where everything must be easier and safer. There are already plenty of safe activities in life. I skip the odd clip at the indoor wall; the quickdraws are often so close together, you could essentially top-rope the whole route. So live a little, and embrace the fear; you’ll be surprised where it takes you.

The consequences when something goes wrong when alpine climbing can be very serious indeed

Interestingly, despite climbing in remote mountains around the world for many years, I still don’t talk openly about the danger involved. I’m not arrogant; I just try to take a clinical approach. I know the risks and consequences. I consider, mitigate, and act. Is this normal? Have years of gently pushing the limits, given me a different perspective? Or am I simply ‘used to it’?

If our ability to deal with risk is simply related to our exposure to it, could we eventually solo Yosemite’s El Capitan, like Alex Honnold, given the technical ability? I’d encourage research on other climbers, racing drivers, and BASE jumpers. All high-level athletes are obsessed. But the difference with alpine climbing is the high-stakes nature of the game. An Olympic sprinter doesn’t pay the ultimate price if they come half a second late across the line.

I was recently forced, though, to revise my attitude to risk. In September 2019, after travelling for nearly a week, four friends and I set up Base Camp in the Hindu Raj, in the far northern section of Pakistan’s Karakoram mountains. This remote and poor region, which borders Afghanistan, hadn’t been climbed in for forty years due to political instability. After making the first ascent of a new alpine route on the north west face of Koyo Zom (6877m), Ally Swinton and I walked back down the Pechus glacier, hungry for Base Camp. We’d been alone in the mountains for seven days.

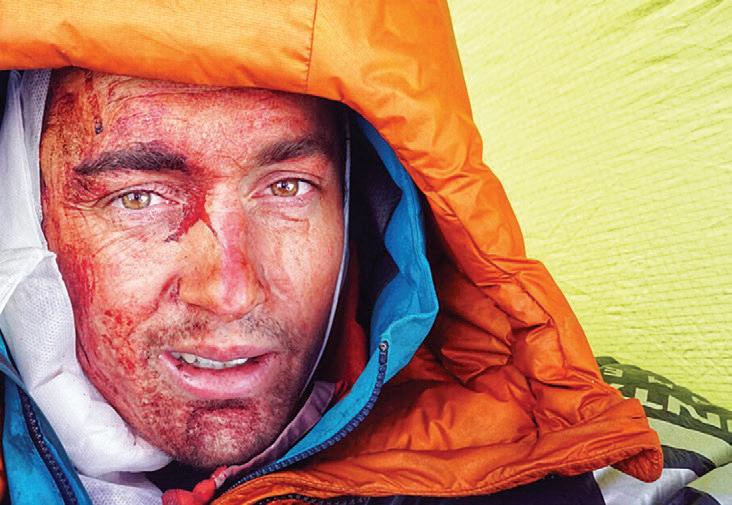

In a sudden, unlucky instant, Ally broke through a snow bridge and fell 15 or 20 metres into a large crevasse. He suddenly vanished into the dark, icy slot, the rope between us whizzing through my gloved hands. Unable to touch the walls, he spun slowly in mid-air. When I pulled him out, I was as shocked as he was. Blood from a head injury ran down his face, and he limped from a badly bruised leg. I tried to think through the adrenaline, our single bandage giving only an illusion of first aid. We were days from a hospital, and, at 5900m, close to the altitude limit of the Pakistani rescue helicopters. Ally needed medical help relatively quickly: I pressed the SOS button on our Garmin InReach Mini.

On the first day, the helicopters couldn’t reach us. Ally’s condition deteriorated as the temperatures dropped at dusk, and I feared the worst. Thankfully, though, Ally’s mind - and head - are very tough. After a long night spent keeping him warm in our double sleeping bag, we were rescued the following afternoon. It was our eighth day in the mountains.

I now know the extent of the consequences of pressing the SOS button on our Garmin. We set in motion international processes, from insurance companies to rescue services, and between the UK Foreign Office and Pakistani Consulates. Whilst Ally and I shivered and shared our final energy gels, our friends were constantly on the phone, coordinating a rescue that was much more complex than we realised.

Our experience gave me an insight into this hidden world. Speaking with staff at the British Consulate in Pakistan afterwards, I realised we were slightly naive towards our situation, and didn’t fully appreciate the amount of work involved to facilitate a rescue. We were lucky the helicopters flew at all; had the visibility been poor, which it often is at high altitudes, the rescue would have been impossible. We were fortunate to be fully recovered. I also now always wear a helmet when walking on a glacier, and am much more aware of what lies beneath the surface.

Ally and I felt like we were relatively in control - until we weren’t - during our new route. We chose an objectively ‘safe’ line on Koyo Zom. We received regular weather updates. We pushed the pitches higher whilst still remaining within our comfort zones. But what happens when you’re unlucky?

To understand more about risk in alpine climbing, I spoke to my Dad, Julian. We learnt to climb together ten years ago. He instilled strong ideas. ‘Wear your helmet; put lots of gear in; and don’t fall off,’ he’d say. I asked him about my big trips to the Greater Ranges. ‘No news is good news when you’re climbing,’ he said. ‘And it’s better to hear about the route afterwards, when we know you’re down safe.’ But he still goes into the hills, and his motivations are similar to mine: ‘I’m just drawn to climbing by a love of the mountains. It’s simply incredible up there.’

It helps that Dad can relate to risk and commitment. During his ocean crossings in a friend’s 38-foot yacht, he feels comfort in the strength of the boat, equipment and crew. ‘Even during the longest storm, four whole days of Force 8, we knew we’d probably be fine even if the mast snapped. I know the boat was built to withstand that kind of weather.’

In an unlucky instant, Ally suddenly vanished 20 metres down into the dark, icy slot, the rope whizzing through my gloved hands

‘If you take risk out of climbing, it’s not climbing any more,’ said Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia. He points out just how intrinsic danger has been within the history of climbing. Some of my richest experiences have come from perfectly-balanced moments of risk and reward. When I soloed Left Wall, a classic route on Dinas Cromlech in North Wales, I knew I could climb it without falling; I was also completely aware of my actions. When I shook out on a jug at half-height, only the fingers on my left hand and the inside edge of my right foot kept me on the rock.

I topped out and sat peacefully, stretching my toes in the warm updraft funneling up the crag. The purple heather in the Llanberis Pass twitched in the breeze, and flashes of sunlight moved over Crib Goch. If I’d simply had another lap on the route, it would’ve been fun. But this was something different. I was buzzing with adrenaline, and the air was alive with electricity. I felt a mile high, perched up there on the crag. This is the reason I climb.