URBAN RENEWAL OF AL SHAWARBY STREET

Developments in Downtown Cairo through Tactical Urbanism

Supervisor: Professor Michele Roda

Author:

Basma Tarek Fadel

Master Thesis in Sustaible Architecture and Landcape Design Departement of Architecture and Urban Studies Politecnico di Milano 2022

by Basma Tarek Fadel

by Basma Tarek Fadel

2

4

5

to the Martyrs of the January 25th

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-55887869

Dedicated

Revolution

6

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work conducted in this thesis would not have been possible without the constant support of many people.

I would first like to thank my professor, Michele Roda, for his continuous guidance, encouragement and efforts to enrich my knowledge during this research process which helped me to successfully complete this thesis.

I would also like to thank the shop owners of Al Shawarby Street for their hospitality and for sharing their stories about the history of Al Shawarby and its current situation.

I express my gratitude and appreciation to my father, mother and my family for their support not only during this thesis but throughout my life and academic career.

Last but not least, I would like to thank Yara, Tala, Ilaya, Youssef, Almo, Mohamed, Salman, Silawy and Oscar for the help they offered in the toughest final hours of this work process.

7

ABSTRACT

The most memorable public places in our cities and towns are generally those places where people congregate on foot - the streets, parks, and squares. These are democratic places that make our towns and cities livable and vital. Our streets especially have a significant responsibility to be accessible to all, and to be functional, safe, and attractive places to walk. They were — and continue to be — the first element to mark the status of a place, from a chaotic and unplanned settlement to a well established town or city.

Congested cities such as Cairo undergo a continuous decline of the quality of its public spaces . This is identified in commercial streets that mostly function as traffic conduits due to high congestion which leads to the deterioration of the urban environment rather than act as livable spaces that could be comfortably shared by all users. Hence, this paper investigates the concept of reclaiming Cairo streets as public spaces for people through Tactical Urbanism — an emerging approach aimed at the gradual recovery of public spaces through alternative actions to conventional planning.

Firstly, it attempts to identify the benefits of Tactical Urbanism. Secondly, to analyze the precedent approaches to reclaiming streets through Tactical urbanism in global review. Then it will look back on the history of Al-Shawarby Street to understand better its heritage and identity within the urban tissue but also the relationship and value people hold towards that street. After a deeper understanding of the connection that locals have with Al-Shawarby, this paper attempts to introduce a creative implementation.

Key Words: Tactical Urbanism - Urban Regeneration - Street as Space - Public Engagement - Space for People - Public Space

9

10

ASTRATTO

I luoghi pubblici più memorabili nelle nostre città e paesi sono generalmente quei luoghi in cui le persone si radunano a piedi: le strade, i parchi e le piazze. Questi sono luoghi democratici che rendono vivibili e vitali le nostre città. Le nostre strade in particolare hanno la responsabilità significativa di essere accessibili a tutti e di essere luoghi funzionali, sicuri e attraenti in cui camminare. Erano - e continuano ad essere - il primo elemento a segnare lo status di un luogo, da insediamento caotico e non pianificato a una città ben consolidata.

Città congestionate come il Cairo subiscono un continuo declino della qualità dei suoi spazi pubblici. Questa è individuata in strade commerciali che per lo più fungono da condutture del traffico a causa dell’elevata congestione che porta al degrado dell’ambiente urbano piuttosto che fungere da spazi vivibili che potrebbero essere comodamente condivisi da tutti gli utenti. Pertanto, questo articolo indaga il concetto di reclamare le strade del Cairo come spazi pubblici per le persone attraverso l’urbanistica tattica, un approccio emergente volto al graduale recupero degli spazi pubblici attraverso azioni alternative alla pianificazione convenzionale.

In primo luogo, tenta di identificare i vantaggi dell’urbanistica tattica. In secondo luogo, analizzare i precedenti approcci alla bonifica delle strade attraverso l’urbanistica tattica nella revisione globale. Quindi guarderà indietro alla storia di AlShawarby Street per comprenderne meglio il patrimonio e l’identità all’interno del tessuto urbano, ma anche il rapporto e il valore che le persone hanno nei confronti di quella strada. Dopo una comprensione più approfondita della connessione che la gente del posto ha con Al-Shawarby, questo documento tenta di introdurre un’implementazione creativa.

Parole Chiave: Urbanistica Tattica - Rigenerazione Urbana - La strada come spazio - Impegno Pubblico - Spazio per le Persone - Spazio Pubblico

11

12

13

Dedication Acknowledgements Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Theoretical Framework 3. Setting the Scene 4. Unpacking the Site 5. Design Proposal: The Rebirth of Al Shawarby 6. Conclusion Bibliography

CONTENT

14 1 2 3 4 5 6 SETTING THE SCENE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK UNPACKING THE SITE DESIGN PROPOSAL CONCLUSION

15 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Research Question 1.3 Aims and Objectives 1.4 Scope and Limitation 1.5 Methodology

This paper is an individual investigation on the role that tactical urbanism can hold in urban regeneration and reclamation of spaces in a densely populated city. Based on its rising popularity in the past decade and many successful interventions in various cities around the world, this research aims to understand how these kinds of projects were able to transform cities into places where people hold a sense of belonging and inclusivity.

Numerous ancient cities were well-known for being livable. However, when more detrimental effects emerged, vehicles began to take precedence over pedestrians who gradually lost their feeling of place, and these cities began to lose this feature. In response, people left the center of the city in search of vibrant neighborhoods with inviting streets where the essential functions of human life could be carried out. Since ancient times, streets have played a critical role in cities: they connected spaces, people and goods, and facilitated commerce, social interaction and mobility. Until the mid-20th century, streets, together with plazas and squares, were an integrated system of movement space that contributed to defining the cultural, social, economic and political life of cities. They had a natural vibrancy and were dynamic and multi-functional places, in particular for young people and teenagers who were (and still are) the main actors in the process of public space appropriation (Torricelli et. al. 2014).

1.1 INTRODUCTION

16

“Our cities need to change, fast. Tactical urbanism is a guided tour of solutions created when local people decide they cant wait for the politics to catch up before they improve their neighborhoods.”

- Alex Steffen

Urban dwellers have historically engaged in a sort of tactical urbanism that involves reusing vacant spaces with temporary materials to create more lively public areas. Tactical urbanism, however, has evolved into a movement during the last few years. Urban practitioners have discovered temporary interventions to be a successful strategy for determining what works and putting programs on the ground after becoming frustrated by delayed, expensive, and frequently exclusive project delivery approaches. By allowing people to really experience what is possible rather than just seeing images, these temporary projects can inspire meaningful public interaction and build support for long-term initiatives. A particular public space’s success depends on more than just the architect, urban designer, or town planner; it also depends on how people occupy, manage, and embrace the area. People make places, more than places make people.

The fundamental guide for urban transformation is “Tactical Urbanism”, written by the movement’s co-founders Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia. The authors start off by providing a thorough background on the Tactical Urbanism movement, including its relationship to earlier social, political, and urban planning movements. The book offers a thorough toolkit for coming up with, planning, and implementing initiatives, along with guidelines on how to adjust them in response to local needs and limitations. Pop-up parks and open streets programs are just two examples of the short-term, community-based projects that have emerged as a dynamic and flexible new weapon for urban activists, planners, and policy-makers looking to promote long-lasting improvements in their cities and beyond. The core of the tactical urbanism movement is these rapid, typically inexpensive, and innovative initiatives.

17 INTRODUCTION

Considering the latter, as well as establishing a theoretical framework referencing the works of Lydon and Garcia, this thesis focuses on Al Shawarby Street located in Downtown Cairo, Egypt. Cairo is often considered the cultural capital of the Arab Middle East. With its massive bazaar, notable mosques, and historically important film industry, the city’s vibrant culture is on full display. However, the city congestion is continuously rising with the increasing population density at 2% per year, leading to an overcrowded city with fewer public spaces. Streets have been taken over by motorized vehicles making the pedestrian experience unsafe and unpleasant. In addition, as this research focuses on Al Shawarby, it is important to note that it was one of the most important streets in that area. However, over time, the street which was a destination spot, lost its identity and status. In order to rebuilt the cultural identity and heritage of the street and regenerate the area, Tactical Urbanism will be the tool guiding the transformations and interventions proposed in Al Shawarby. This will not only bring back the buried identity of the street but also reshape the center of Cairo into a pedestrian friendly, inclusive and vibrant area.

To conclude, Tactical Urbanism was the core for the rejuvenation and transformation of many cities around the world. It allows people to feel included in the process and gives them the power to voice their needs. The movement holds the ability to be the driving force behind rethinking public spaces in Cairo as well as act as a catalyst for remolding the urban construct of the city into a more sustainable and human scale approach.

18

1.2 RESEARCH QUESTION

1. What are the different tools and solutions involved in reclaiming and repurposing a street?

2. What is the role of Tactical Urbanism in regards to revitalizing and reclaiming public spaces?

3. How can these methods be carried out in the context of a dense and highly valued cultural and historical background to regenerate and ameliorate the quality of life?

1.3 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

Based on the principals established by Mike Lydon “Short-term Action, Long-Term Change”, this thesis aims to understand and explore the various possibilities and scenarios that could play out in a densely packed city using Al Shawarby Street, Cairo DT as a case study.

The main objectives of this paper are as follows:

Understand the role the local culture and customs play in shaping the identity of Al Shawarby in order to bring back its former glory.

Develop a series of suitable scenarios through Tactical Urbanism that are adapted to the lifestyle of the people and reclaim the lost spaces of Al Shawarby.

Transform Al Shawarby from a place of passage to an attractive spot making of it a destination.

Increase the quality of life for the citizens of Cairo by introducing a holistic network of activities that cater to the needs of everyone making it an inclusive street for all.

Establishing a connection between people and their sense of place.

19 INTRODUCTION

This thesis will dive into the possibilities and flexibility enable by the implementation of Tactical Urbanism techniques in order to reclaim public spaces and enhance the quality of life creating a place that morphs to serve everyone.

1.4 SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS

Based on the objectives of this thesis and the research problem at hand, this paper seeks to follow qualitative methods to provide rich, contextual explorations of the topic through case studies, surveys, interviews conducted on site. In addition, it will be guided by a theoretical framework, followed by a historical analysis as well as of the current situation of the case study. Finally, a toolkit with the proposed interventions will be developed that responds directly to the research problem.

1.5 METHODOLOGY

20

21 INTRODUCTION

22 1 2 3 4 5 6 INTRODUCTION SETTING THE SCENE UNPACKING THE SITE DESIGN PROPOSAL CONCLUSION

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Definitions

2.1 What is tactical urbanism? 2.2 Why did it start? 2.3 When and where? 2.4 Cases Studies 2.5 What is street regeneration? 2.6 Why regeneration and reclamation of streets? 2.7 Solutions to regenerate a street 2.8 Case Studies 2.9 Conclusion

23

tac·ti·cal adj: \ t a k - t i - k ə l \ 1. of or relating to small-scale actions serving a larger purpose 2. adroit in planning or maneuvering to accomplish a purpose.

The Tactical Urbanism movement, or ‘guerilla urbanism’ was created in combination with other movements, and enables a variety of local actors to test new ideas before making significant political and financial commitments.

Tactical urbanism has the following five features, defined by The Street Plans Collaborative: gradual instigation, addressing local planning constraints, feasible and short term, low risk-high reward, and stakeholder capacity building. It is occasionally sanctioned, but not always.

Cities have witnessed urban space modifications over the past few decades thanks to interventions that are vibrant, adaptable, and light. These kinds of projects are now more frequently seen in both small towns and major cities. Acting as an innovative design strategy, tactical urbanism is put out in an effort to promote long-term urban regeneration using immediate measures. Projects that were originally considered transitory have in some circumstances turned out to be permanent because of the positive effects that these interventions have had on the urban environment.

Tactical tools can enhance the liveability of a whole city by operating at the scale of a street, a block, or a building. A “tactical” project can result in positive changes in an entire neighborhood, much like how acupuncture puts needles into one area of the body to improve the health of the entire organism. It can be seen as a tool for executing innovative ideas with high communicative value that strive to improve public areas or perhaps envision entirely new ones. The scope, size, budget, and support of tactical

2.1 WHAT IS TACTICAL URBANISM?

24

interventions might vary significantly. However, they all aim to creatively rethink public space, which is a shared objective.

Being a flexible movement that shapeshifts and adapts to its context, there is no single definition of tactical urbanism that positions it within the larger context of urban planning, therefore it can take many different forms. The presence of empty lots, disorganized shops, parking lots, and other unused locations is still very noticeable. Tactical urbanism allowed people or government members to experiment with this, which frequently resulted in innovation. The application of tactical urbanism may spur advancement in placemaking. The public, who are the end consumers, are allowed to participate. The alternative options are tangible to citizens since they are simple to carry out.

In the words of Mike Lydon, tactical urbanism is “short-term action for long-term change”. A fantastic illustration of this are the popular temporary pop-up bike lanes that appeared in numerous locations during the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020. They are inexpensive, straightforward, and only ephemeral fixes, but they aim to make broader changes, such as enhancing cyclist safety and space quality. “Designing cities for people, not cars is the impetus behind many tactical urbanism projects.” (O. Currie, 2021). A classic example of how to design cities for people rather than cars is Copenhagen’s renowned planner Jan Gehl. Other themes that facilitate change in urban planning include environmentalism, the sharing economy, sustainability, and technological advancement. Opportunities for tactical urbanism arise from demographic shifts and even economic downturns.

25 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Tactical urbanism is overtaking the globe, from pop-up parks to guerilla gardening. The short term modification of urban infrastructure by citizen-led initiatives is a defining feature of the expanding movement. These initiatives are low-cost and aimed towards enhancing the practicability, security, and attractiveness of neighborhoods and public spaces.

The movement was conceived as a way for activists to speed up change in their communities because of their discontent with the lengthy and complicated process of getting infrastructure improvements approved by the city. These changes take place at the local level. They often showcase cultural values and improve the standard of social interaction. Since cultures and ethnicities are frequently mixed in cities, there are numerous ways for ideas to be conveyed in the communities. Impactful thoughts result from having a close knowledge with the context.

Through tactical urbanism, people can take back the streets and unravel a variety of innovative solutions to increase the functionality of an area and turn it into a safe and user friendly space. An example of an action where citizens took the matter in their own hands, is in the city of Delft, Netherlands, and fragmented the asphalt of the street during the night. The goal was to force the cars to slow down and drive carefully through the street allowing people to bike, walk and play on the street itself. The action was successful and later supported by the government which converted it into a permanent transformation.

2.2 WHY DID IT START?

26

“First life, then spaces, then buildings. The other way around never works.” –Jan Gehl

In addition, the tactical urbanism movement saw an extreme increase in popularity during the COVID period. With the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, cities had to rethink their streets and many changes done to adapt to the situation became permanent transformations. For example, the streets of New York were the host of The Open Restaurants program. The initiative was launched during the COVID pandemic to allow outdoor dining while keeping safe distance by taking out space from on-street parking. Through this project which became permanent and will be overseen by NYC DOT, restaurants will be able to use the sidewalk and curbside area in front of their establishments for outdoor dining from now on.

2.3 WHEN AND WHERE?

The power of tactical urbanism is that it has converted both individual and public opposition into a motivation in addition to being a flexible response to the constrained conditions of the twenty-first century. The hesitant and apprehensive beginning of the disappointed and difficult process of public engagement is followed by an uptick as confidence is restored by tactical urbanist movements.

Going back in time, Les Bouquinistes in Paris, France, are proof that tactical urbanism is nothing new. France’s Les Bouquinistes provide as evidence that tactical urbanism is nothing new. Unauthorized book merchants started assembling along the Seine River banks in the 16th century to promote the current bestselling books. Though physical bookshop owners protested strongly enough to get the booksellers outlawed in 1649. Les bouquinistes were undeterred and became so popular that the city eventually had to permit their existence. Regulations, however, limited them to particular areas and required that each “store”

27 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

must shrink into a box at the end of the day. The Les Bouquinistes area was later named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2007, making this tactic one of the most renowned, if not the slowest, examples of tactical urbanism.

Fast forward to 2008, Mike Lydon was inspired by his lonely bike trip to work in Miami and suggested to make cycling safer and more inviting for cyclists. The route from Miami Beach to Miami’s Little Havana neighborhood was the starting point of Lydon’s intervention. After receiving the support of his collegues and friends, soon enough the government took interest in his project and proposal masterplans were suggested. Early intervention successes include appointing a bicycle coordinator, increasing the availability of bicycle parking across many neighborhoods, including bikeway infrastructure in city projects, implementing a full streets ordinance, establishing Bike Miami Days, a renowned open streets initiative. At the initial event in November 2008, thousands of locals attended. Along generally carfilled streets, people were not just cycling but also walking, jogging, skating, and dancing. The

28

On the dock of the Grands Augustins - the 1900s

effectiveness was instant and quite evident, and the uniqueness of the event generated an almost physical, thrilling buzz on the street. The event’s main benefit was that it gave citizens a brand-new and intriguing perspective on their city. Additionally, it allowed them a chance to envision an alternative urban future in which creating more public space and facilitating walking and bicycling would be simpler.

Another early intiative was led by

commissioner of the New York City Department of Transportation, where she experimented with the

29 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Janette Sadik-Khan,

Bike Miami Days debuted in 2008. (Mike Lydon)

Road from Miami Beach to Miami’s Little Havana neighborhood

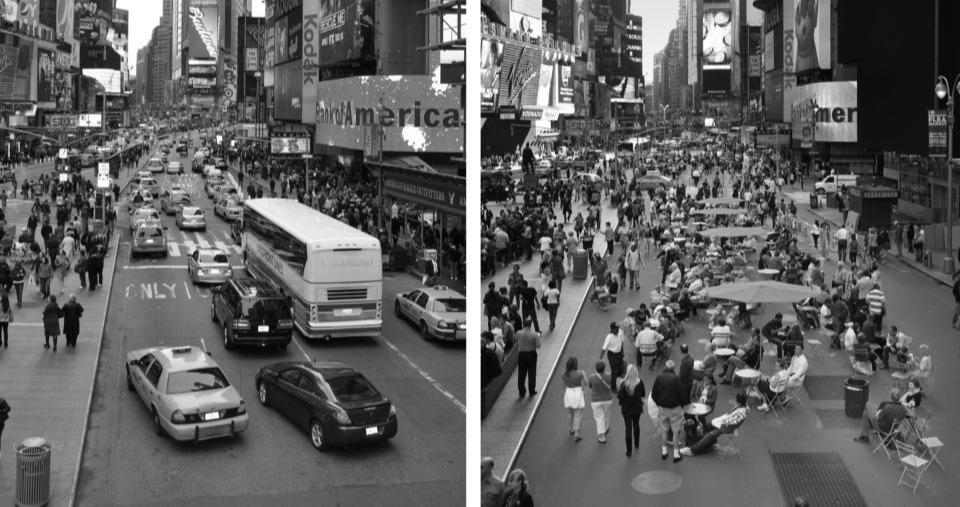

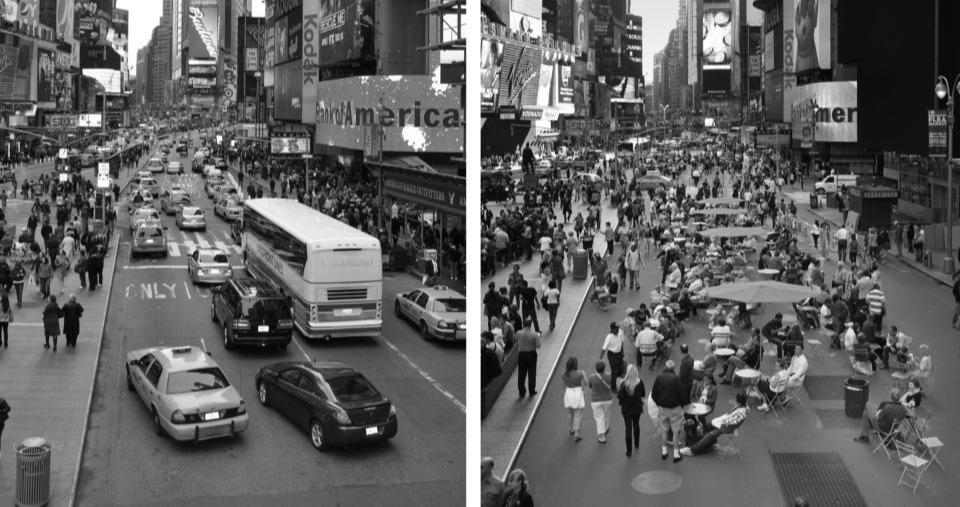

introduction of pedestrian plazas in various spots within NYC. She also introduced 650Km of cycling lane along the city. Furthermore, in order to establish a large car-free area, they famously closed Broadway through Times Square in 2009 and constructed 60 new pedestrian plazas. The area was transformed from an asphalt and grey space to a vibrant and attractive environment that prioritizes pedestrians.

All New Yorkers should live within a 10-minute walk to a pleasant open space, according to the 2007-launched NYC Plaza Program. In order to encourage a public-private form of partnership between local communities and the DOT, public plazas were created in the place of underutilized street space. The Plaza Program, which is frequently cited as an illustration of tactical urbanism, uses portable street furniture and ephemeral materials to overnight convert refuge islands into pedestrian plazas. At the intersection of Pearl Street and DUMBO in 2007, DOT constructed its first plaza. “Next to safety and mobility, which should be the first considerations, the economic power of sustainable streets is probably the strongest argument for implementing dramatic change.” stated Janette Sadik-Khan.

30

New York’s Times Square transformation started as an interim project – Photo credit: NACTO-GDCI

Tactical urbanism is overcoming its reputation as a “guerrilla” or unlawful strategy and is instead becoming a preferred technique for forwardthinking local authorities, developers, or nonprofits. This strategy is now being used all over the world, not just in New York City and in San Francisco, where the Pavement to Parks program sparked the rapid spread of parklets. Because they are impactful, these modest yet effective interventions are becoming more common.

31 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Installation of a new pedestrian plaza at Pearl Street Triangle in DUMBO. Image courtesy: NYC Department of Transportation

Parklet in San Francisco

Tactical urbanism takes on various forms that result from different actions based on the needs of the community. Some of the most popular interventions consist of chair bombing that reuses leftover materials to create public seating that are positioned in areas that lack public furniture, de-fencing to break down barriers between neighbours and encourage community building. Other actions include guerilla gardening, pop-up cafes or parklets, depaving, crosswalk painting and much more.

According to a webinar done by Skye Duncan Director of NACTO-GDCI and Mike Lydon Principal of Street Plans Collaborative, a list of the five main lessons learnt over the various interventions that allows them to go from a temporary action to a permanent project was combined. The most crucial point is to uncover the hidden gems in the neighborhood, vacant areas that are overlooked or abandoned. Often these spaces need a little touch of color to be brought back to life. The next step would be to reach out to the public and engage citizens as well as stakeholders. This allows to build community support and helps them understand better the urban issue at hand. Once the locals are engaged and the proposed intervention is agreed upon, the more technical part follows where measurements and drawings should be established for an optimal proposal. The next steps is of the utmost importance, attracting people to the re-imagined area. This can be done using vibrant and colorful materials, organizing events, music and more to activate the space and make it inviting for people. Finally, after an evident success of a project, future policies and detailed planning are established over time to transform the ephemeral intervention into a permanent design. These small and low cost changes can be the starting point that inspire larger scale interventions aiming to make cities more pedestrian friendly.

32

Later on, tactical urbanism spread quickly around the world with an increase in popularity and interest. Using the work of Mike Lydon as a reference, various countries around the world , such as Italy, Australia, Latin America, India and more, started implementing tactics to better the quality of life in neighborhoods. The approach taken is to develop short-term scenarios that highlight a particular issue and the development of unique interventions to address it, while attempting to involve the community to give the projects significance and improve their sustainability over time. By doing this, the discussion about the advantages of the projects for the quality of life in the context in which they are inserted is sparked. These re-designed areas hold a high social value as they compose a space where people come together, interact and exchange ideas.

33 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

“The brain tends to remember 10% of what it reads, 20% of what it hears, but 90% of what it does or simulates.”Edgar Dale

34

“The barriers to change is us. If we can make lots of great things happen

35

we break down those barriers, we happen very quickly.” - Mike Lydon

Milan from Open Squares to Open StreetsPiazza Spoleto and Via Pacini Interventions

The “Piazze Aperte” program, designed in association with Bloomberg Associates, NACTO, and GDCI, was introduced by the City of Milan in September 2018. Tactical urbanism is a driving factor of the program, used to “create public spaces in place of unnecessary roadways or crossroads by the execution of light, quick, and affordable interventions in Experimental Way.” Before devoting time and resources to a permanent structural arrangement, the interventions’ temporary nature enables swift action and reversible solution testing, anticipating the consequences with immediate benefits and assisting the decision-making process towards a permanent solution.

The Municipality issued a public notice the following year inviting all citizens to submit proposals for interventions in public areas using the social nature principles that were part of the original tactical urbanism concept and involving local residents in neighborhood-scale urban regeneration processes. The outcome of the initial experiments leads, at least initially when the colors on the asphalt are bright and brilliant, to an impressive aesthetic effect in terms of street furniture, but larger issues encompass the management of traffic, that must be thoroughly examined before the implementation where vital space is taken away from the road system.

The new “open square” in North Loreto neighborhood is a multicolored pedestrian area in front of the elementary school Cerisola. It is located between via Spoleto, via Venini, and via Martiri Oscuri. The pavement is colored in shades of yellow, blue, and blue. There are also flower boxes, racks, benches, and ping pong tables there.

2.4 CASE STUDIES

36

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The new area, which satisfies the desires of the Cerisola School families, serves to both make it safer for kids to enter and depart the building and to give locals a new gathering spot for social interaction.

Through innovative senses, bike lanes, and pedestrian walkways, the integral rethinking sought to slow down and diffuse the crossing traffic. The piazza that was once car-chocked is now prioritizing pedestrians. The space is inviting with its vibrant colors and street furniture. The intervention resulted in a destination spot not just for adults but also for kids who can safely enjoy and play.

38

Milano, via Venini (foto Comune di Milano)

Piazza Spoleto, Milano. People enjoying the public seating

Another example of the measures taken in the city of Milan, is the revamp of Via Pacini into a pdestrian friendly street. The tactical urban planning in this case was handled by Apicultura Studio, a team of young architects and engineers located in Milan. In accordance with a “Collaboration Pact” between the Municipality and the Citizens, this is the requalification of a fraction of the street done by Retake Milano volunteers using paint and brushes after the municipal employees had placed new benches and bike racks in the months prior. The center reservation has been enhanced with additional benches, two picnic tables, and bike racks for a distance of around fifty meters. The central reservation is already partially furnished with benches and partially free of parked automobiles.

Thousands of similar examples exist around the city of Milan. These tactical interventions experienced a spike in their popularity especially during the pandemic. As Milan was one of the majorly affected cities, urban planners were quick to rethink public spaces and adapt them to the current situation.

39 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Via Pacini (foto BG/Sport&Impianti)

Better Block, Kansas City, USA

BNIM oversaw the Grand Boulevard Streetscape Plan, which recognized and developed a long-term vision for a rejuvenated Grand Boulevard. Grand Boulevard was initially intended to be” grand”. The streetscape plan incorporates entire street concepts, with a major emphasis on transit and new cycling facilities, and envisions a safe, livable, and walkable downtown.

In 2012, “Better Block KC” was established in order to further the discussion and build the necessary support for the “great” shift. Between 16th and 17th Streets, Grand Boulevard was transformed into a real-world example of a green, finished, and livable community asset. Provisional trees, lighting, landscaping, pedestrian crossings, cycle paths, street furniture, and other elements changed the look of the cityscape. Pop-up companies, local vendors, artists, and entertainers all had the potential to make the neighborhood more vibrant.

40

Temporary streetscape by Better Block

Vacant spaces, unoccupied storefronts, deteriorated structures and sparsely used parking lots very broad roads for driving. This gloomy scene may be seen in practically all American cities. Moreover, despite the fact that many urban communities are prospering, too many have not bounced back after a half-century of systemic underinvestment. (from Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Action for Long-Term Change, Island Press)

The intervention initiated by “Better Block KC” tries to transform these abandoned or overlooked places along the wide road into safer spaces for pedestrians and cyclists while meeting the needs of the communtity.

The tools used to create the project are ephemeral materials that can be easily removed, adjusted or transformed to fit the context in the most optimal way. “The Tactical Urbanist’s Guide to Materials and Design,” goes into the details of pop-up urbanism and the circumstances to consider in order to choose the right materials. Based on whether an initiative is a demonstration, trial, intermediate design, or permanent, long-term

42

Street transformation by Better Block in Kansas City

installation, different materials and strategies are required. It’s frequently not essential or practicable to employ long-lasting materials from the beginning of a tactical urbanism project because the purpose is frequently to test a design that could eventually become permanent in the short term. The materials used in this intervention are scraps collected from the community. People donated some chais, planters, food trucks and created the first pedestrian extention on the street. The project came to life with people occupying the space. It attracted locals of all age groups

The City of Dallas subsequently requested that the same strategy for rapid regeneration be applied in other sites after the inaugural Better Block initiative was such a success. Patrick Kennedy, a blogger and planner from Dallas, published an article that perfectly encapsulated the ethos of Tactical Urbanism as a whole, not simply the original Better Block project “Where bureaucracy, political timidity, or ineptitude all too often prevent places for people, the Better Block just did it, inspired by an outgrowth of frustration with all of the above.”

43 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Planters added as barrier in Kansas City

Cairo City and Tactical Urbanism

Tactical urbanism can be an effective solution for many spots in Cairo’s urban fabric. “Tactics” work from the bottom-up, implemented developing designs at the finer scales in an experimental, adaptable, temporary or evolutionary way which affect smaller urban areas, that have potential to affect positively and negatively other systems in the urban network, however, the impact of traditional strategic approach, doesn’t appear during whole network. (L. King, K., 2012).

Some neighborhoods in Cairo have residents who engage in activities that are restricted in many public areas and removed from contemporary urban life, creating a general sense of being unable to participate in the public life.

From historic events like Al-Mulid, consolation pavilions, and wedding tents to monthly market events, tactical urbanism activities may be seen in Cairo’s urban spaces and streets in a variety of ways.

The youth and associations initiatives that are concerned with urban and socioeconomic development, recreational activities organizations, or cultural movements are another type of these strategy actions.

One of the examples of tactical projects in Cairo is the Commemoration of the holy figures commonly known as “Al-Mulid”. Al-Mulid, which translates to “birthday” in Arabic, is a celebration held every year to honor the saints of holy figures by remembering their birthdates. These celebration ceremonies are typically organized in the streets and urban areas surrounding mosques. It takes a while to prepare for this well-known custom; temporary tents were placed inside spaces

44

lighting fixtures, and loudspeakers were installed, traders grew daily, along with visitors from several towns for this special occasion, and it got increasingly difficult to move as crowds grew over time to see the numerous spectacles and sceneries. After the ceremony, tents are taken down as the traveling carnivals move on to the next event. (Egypt Tour, 2015). The “creative space” that hosts ceremonies by taking advantage of public areas and engaging in ritual acts that are modified throughout the day and into the night.

46

Urban space with equipment and tents installed and visitors coming to the carnival

Tents and entertainment equipment stored before carnival’s night

Another popular tactic is the weekly friday market organised. There are roughly seven weekly markets in Cairo, according to the Informal Settlements Development Fund (ISDF).

These well-liked local markets include flea markets where many items, including junk, ornaments, and treasure, can be sold at low prices to thousands of people who are drawn there each week from various districts. Low- to middle-class Cairo residents can find all of their requirements at these regular bazaar. Vendors and stalls are positioned close to one another along narrow lanes and in between homes and shacks.

47 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

“We

to some streets more often than others… Maybe a street unlocks memories, or offers expectations of something pleasant to be seen, or the possibility of meeting someone old, or someone new... Because some streets are more pleasant than others, we go out of our way to be on them.” - Allan B. Jacobs

Globally, the population of urban regions is steadily growing. As a result, there is an urgent need for the radical development of local infrastructure. This places tremendous strain on resources generally. Therefore, one of the most significant development concerns of the twenty-first century is managing urban areas.

Urban life depends heavily on the built environment. The function, image, and cultural memory of a city are all influenced by its streets, which are essential to a city’s overall development. “ Streets are the city”; they serve as more than just conduits for people and products. Everybody can engage in public life on the streets. We are reminded that streets can be places for people, honoring local culture, neighborhood identity, and “life between buildings” (Gehl, J. ,1971). The possibilities of investing in public spaces can be displayed by citizens temporarily transforming streets using readily available items like home paint, traffic cones, cloth, and even chalk.

Urban regeneration is a strategy used in city planning to address the social and economic issues that exist in urban areas while also enhancing the city’s physical and natural and built environment.

2.5 WHAT IS STREET REGENERATION?

48

go back

Urban renewal tries to turn abandoned or neglected portions of a community into ones that are economically viable.

What does urban regeneration actually mean, then? It denotes a comprehensive approach to urban planning and a commitment to social inclusion as well as energy efficiency. These projects are complex, time-consuming, and face the challenge of gentrifying private space or privatizing public space. However, they are intended to recover unused assets and repurpose resources, enhancing urban prosperity and quality of life.

The challenge at hand is brought on by the relocation of economic activity from inner cities to their peripheries, which has left many urban cores plagued by unemployment, subpar services, housing, and deteriorating streets and public spaces. As a result, citizens are no longer able to benefit from possibilities in wealthier neighborhoods, which has hampered the capacity of urban centers to boost city economy. Urban regeneration calls for a variety of measures, including brownfield redevelopment, densification and intensification tactics, economic activity diversification, historical conservation and reuse, public space activation, and improved service delivery.

There are areas of fragile and degenerating urban regions or vacant and neglected land in every city. The reputation, general quality of life, and efficiency of the city are compromised by these areas of unutilized land. Typically, they are the outcome of modifications to urban growth and productivity patterns. “Urban regeneration means the improvement the quality of life and investing in the future.” (Alpopi, C. , 2013)

49 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

By creating more balanced cities, how can we help create a more equal society? Urban mobility is essential to residents’ social and economic well-being in a world that is becoming more urbanized. However, current urban transport networks, which are mainly based on the mobility of private automobiles, have favored road space and operational design of streets for automobiles over other modes of transport, which has had many social, environmental, and economic consequences and reduced urban livability. (Raffo, V. 2014) People living in cities typically spend up to 90% of their time indoors thus creating a disconnect within the community and between people and the built environment. (Schuurmans, A., 2018)

The purpose of various approaches of urban regeneration vary. Taking on growth-related obstacles and lowering the unemployment rate are two examples. In addition to making locations more desirable to investors and residents, maximizing potential in underdeveloped areas, increasing the contentment of residents with their homes, providing disadvantaged populations with opportunities, are some of the reasons why street regeneration is implemented. The main goals of this kind of activity are to support economic development and elevate the standard of living for locals.

The process of transforming streets for nonvehicular use is known as street reclamation. Its main advantages are said to be reduced vehicle

2.6

WHY

REGENERATION AND RECLAMATION OF STREETS?

50

“If you plan cities for cars and traffic, you get cars and traffic. If you plan for people and places, you get people and places.”

- Fred Kent

2.7 SOLUTIONS TO REGENERATE A STREET

traffic, lessening the number of accidents and emissions, lower summer temperatures as a result of increased green space and less tarmac, increasing social and commercial potential due to increased foot traffic, more space for urban dwellers to garden, better co-housing and resident support, such as suburban eco-villages constructed around former streets, for elderly and disabled people While others choose a more political strategy, some proponents take a more tactical approach to the issue of street reclamation.

Creative cities are creating walkable environments at a more human scale in conjunction with a variety of sustainable urban transportation options in order to increase productivity and innovation. Spaces and interpersonal connections are being recreated; contemporary metropolitian dynamics play with both proximity and distance. It also offers a solution to some of the more difficult issues posed by urban poverty, taking into account the larger aspects of social inclusion in addition to access to economic opportunity.

The current trend of cities swapping auto-centric policy tendencies for healthier and greener settings presents an opportunity. Cities all around the world are becoming aware of the need for a new city design that is sustainable and mindful to the issues and difficulties facing urban spaces.

Any regeneration project must be planned with respect to sustainable development and must ensure a high standard of living for those who live and work nearby. Urban regeneration can tackle three different categories: economic, social/ cultural, and environmental.

51 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The goal of economic regeneration is to boost local company growth, employment, income, and skill development. Through both inbound investment and the movement of businesses and households from declining areas, it aims to revitalize local economies. Economic regeneration focuses on developing communities where people desire to live and work. It is strongly related to processes of neighborhood redevelopment as well as social, cultural, and environmental rehabilitation.

Social interventions and practices that emphasize family, parenting, child welfare, unique community circumstances, arts and culture, and health and wellness are referred to as social regeneration.

By addressing harmful social behaviors, this kind of regeneration strives to empower individuals to actively contribute to community life and larger society in a richer, more meaningful, and more mutually beneficial way.

Environmental regeneration emphasizes land rejuvenation through the reclaiming of abandoned land and environmental restoration. This can be accomplished through creating urban green spaces, managing green belts effectively, redeveloping brownfield sites, and carrying out ecologically friendly projects like encouraging walking, bicycling, taking public transportation, and recycling.

Some of the solutions adopted to regenerate a street include, but are not limited to, public art plays which a powerful role in shaping the character of public spaces; policy making, reusing vacant areas or buildings, promotion of greater awareness , limiting car accessibility or speed making the zone mainly pedestrian.

Pedestrian zones, usually referred to as car-free zones, are parts of a city or town that are exclusively accessible by foot and may forbid most or all

52

motor traffic. The process of making a street or location pedestrian only is known as pedestrianization. This seeks to increase the volume of shops and other economic activity in the region, improve the aesthetic beauty of the local environment, and improve pedestrian accessibility and mobility. While pedestrian zones can range in size from a single square to entire districts, with highly varying degrees of dependence on cars for their broader transport links, they often imply a large-scale area that relies on forms of transportation other than the car.

Everyone has a role to play in this, including governments, planners, engineers, development partners, and road user. a difference that save countless pedestrian lives by bringing all interested parties to the same table to execute these solutions in an efficient, coordinated manner can be achieved.

These are some of the solutions available to reclaim a street. They can be implemented in various ways, from following a political procedure to imposing them on the street by the locals. The latter refers to tactical urbanism approach which will be the focal method used in this paper to regenerate and reclaim Al Shawarby Street in Cairo, Egypt.

53 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Shopping Street - ”Strøget”, Copenhagen

Beginning of the 1960s, traffic increased in the inner portions of the historic center, winding streets, as well as in the growing shopping districts surrounding central Copenhagen. Busy pedestrians were also crowding the streets, obstructing traffic with their heavy foot traffic on the constrained sidewalks. Copenhagen’s City Council decided in 1962 to create a car-free pedestrian zone from the western Town Hall Square to Kongens Nytorv (The Kings New Square) in the eastern part of the city called “Stroget” which also includes a large amount of small streets and historical squares spreading out from “Stroget” and the medieval part of Copenhagen. The street system is the eldest and longest pedestrian street network in the world, with a total length of about 3,2 kilometers.

2.8 CASE STUDIES

The regeneration of the street started with a preliminary phase testing the street as a pedestrian. The municipal council then opted to turn the tested area into a permanent “Pedestrian Street” following a successful two-year trial period which

54

former street (1935) longest coffee table in the world from the one end of the pedestrian street to the other (1967)

reduced air pollution, decreased traffic, and many content pedestrians. The street is a part of Copenhagen’s motor-free zone, which is a popular tourist destination and has the world’s longest pedestrian street (Stroget).

It provides a wide variety of dining options, fast food options, sidewalk cafes, boutiques, gift shops, department stores, street performances, theaters, and museums, among other things. Pedestrians VisitorsP are always surrounded by clean air, as well as a peaceful environment all year long, but continually in a busy retail atmosphere, making “Stroget” a haven for true shopaholics. There is always plenty to see and do there.

Piazzas linked to Stroget

The new pedestrian area was examined by architect Jan Gehl beginning in 1962, and his significant reports and conclusions on the subject served as the foundation for Copenhagen’s broader policy change toward emphasizing pedestrians and bicycles.

The strategies of Jan Gehl and Copenhagen have

56

spread influence around the globe, promoting pedestrianization in cities like Melbourne and New York. The project was successful as it adapted to its context. Designing appropriate places for the comfort of pedestrians is one of the most important aspects of modern urbanization and renovation and rehabilitation stimulus of urban old fabrics.

A model and source of inspiration for hundreds of capitals and large towns throughout the world, the Pedestrian and Shopping Street “Strget” has been a huge success from the start and has now been around for 50 years.

57 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Strøget Street

Outdoor entertainment

Sayer Street and The Meadow, London

Lendlease’s fascinating public realm projects Sayer Street and The Meadow at Elephant Park are a component of the larger urban renewal in Elephant & Castle. The Meadow, a playful and biodiverse linear environment, connects to Sayer Street, a modern high street redesign created in partnership with Jan Kattein Architects.

The uncommon task of designing half a high street was given to different designers by Lendlease in 2018. The idea was to take into account everything

58

Picture on Sayer Street. By Jack Hobhouse

that symbolizes the social life of some of London’s most beloved public areas on a strip of land that was only 4m wide and 100m long. The project will support a recently unveiled, carefully planned food and beverage offer on the opposite retail promenade while construction on a permanent structure continues behind a construction hoarding. Sayer Street Central’s design for interim usage was inspired by a goal to build a street with a distinct sense of place, authenticity within the neighborhood, and opportunities for engagement and exploration throughout the day.

A lively and colorful “jungle” planting scheme made up of tall palm trees, lush grass, and meandering climbers creates an immersive environment that stands out against the backdrop of the dense urban fabric. Numerous resilient palm trees were included in the plant choices after consulting to make sure they could tolerate the colder weather. To ensure year-round covering and to add bursts of seasonal color, the herbaceous planting mix is primarily evergreen.

60

Picture on Sayer Street. By Jack Hobhouse

Elephant & Castle station and Sayer Street are connected by a vital pedestrian route known as The Meadow. Lendlease aimed to establish a temporary park on the site that would feed into their larger greening program in order to create unique greenspace, engage the streetscape, and boost biodiversity. Sayer Street was approached with the idea that it would not be a passive installation but rather one that may evolve and transform over the course of the following years.

61 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Picture on Sayer Street. By Jack Hobhouse

The Meadow. By Jack Hobhouse

-

A growing body of studies has been examining the benefits of pedestrian mobility on personal health, sustainable development, and social inclusion for the past decades. In parallel, the demand for a more responsive planning system has led to the interpretation that tactical urbanism projects are an alternative to and a challenge to conventional spatial planning tools. According to some, the defining traits of this new urbanism movement are short-term implementation, a lack of resources, and community involvement. Action is the core of tactical urbanism.

A plan that brings activity and involves the community is one of many elements that contribute to a successful urban environment. Studies on tactical urbanism demonstrate benefits for city revitalizations. An ideal intervention would be able to answer all the guidelines laid down by Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia in “Tactical Urbanism: Short Term Action Long Term Change”.

The different strategies and tools implemented by the cities studied in this paper revolve around engaging and attracting the community primarly, reusing existing resources, creating vibrant and inclusive environments and involving stakeholders.

The focus of this thesis will concentrate on the stategies and tools enlisted below:

2.9 CONCLUSION

62

“Tactical Urbanism demonstrates the huge powerof thinking small about our cities. It shows how, with a little imagination and the resources at hand, cities can unlock the full potential of their streets.”

Janette Sadik-Khan

1. Preservation of the historical heritage.

2. Improving the infrastructure network and connectivity of the area.

3. Reusing or adapting vacant architectural plots or buildings.

4. Creating attactive and interactive public spaces as the key intervention.

Using tactical urbanism as a strategy to regenerate and reclaim a street will result in an inclusive environment within the urban tissue. It was proven times and times again that this approach has a high success rate.

Tactical measures will be explored and used as a framework for the case study of Al Shawarby Street in Downtown Cairo, Egypt.

63

64 1 2 3 4 5 6 INTRODUCTION THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK UNPACKING THE SITE DESIGN PROPOSAL CONCLUSION

65 SETTING THE SCENE 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Location and demography 3.3 Historical background - Downtown Cairo 3.4 Geography and climate 3.5 Cultural background 3.6 The birth of Al Shawarby 3.7 Urban Interventions Through the Years 3.8 Need for regeneration 3.9 Target users

AFRICA EGYPT

AFRICA EGYPT

EGYPT

CAIRO

The largest city in both Africa and the Middle East, Cairo has served as Egypt’s capital for more than a thousand years and is a significant center for politics and culture in the area. With a population of 21.3 million, the Greater Cairo metropolitan area is the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the largest in the Arab world, the largest in the Middle East, and the sixth largest in the world. Due to its geographic proximity to the ancient towns of Memphis and Heliopolis as well as the Giza pyramid complex, Cairo is often connected with ancient Egypt.

Since very early in the 20th century, Egypt has been urbanizing, and the number of people living in cities there seems to be steadily growing.

A multidisciplinary approach is taken to improving quality of life. It emphasizes improving human welfare and well-being. Cairo is one of the world’s most congested cities, and the city’s traffic situation is a serious issue. Cairo’s urban environment is deteriorating as a result of users’ preference for driving over strolling in the streets, and as a result, the city urgently needs to improve the quality of life for its citizens. In light of this, the study problem focuses on developing and planning streets to improve Cairo residents’ quality of life. This is accomplished through researching the connection between city users’ quality of life and non-motorized traffic paths.

The results of a thorough methodology are applied to regional models in Greater Cairo after it has studied the world’s top models. Both the existing models, represented by (Local Case Studies), and the under-construction models, represented by (AlShawarby Street) were separated into two categories. An analytical study will be conducted based on the administration of a questionnaire and site inspections in order to determine the assessment criteria as well as to gauge the users’

3.1 INTRODUCTION

68

standard of living and needs. In order to improve Cairo’s quality of life standards, the research tackles the variables influencing street planning and design.

3.2 LOCATION AND DEMOGRAPHY

Cairo is located on the Nile at a position where the Nile Delta begins to spread up from the flat flood plain, which is constrained by desert hills to the west and the east. Pre-1860 Cairo was confined to a small area of somewhat higher terrain next to the eastern hills. The majority of contemporary urban growth occurred to the west of the ancient city, all the way to the Nile. Cairo’s growth has largely taken place on productive agricultural land. On what was formerly a desert, only the eastern districts have been built.

Cairo has an estimated 2016 population as high as 12 million, with a metropolitan population of 20.5 million, which makes it the largest city in Africa and the Middle East, and the 17th largest metro area in the world.

World Population Review. (2020). Cairo Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs). Worldpopulationreview.com. https://worldpopulationreview.com/ world-cities/cairo-population

69 SETTING THE SCENE

Cairo is a very homogeneous city with very few minority communities. Those that do exist are very small and are not concentrated in specific neighborhoods.

Close to 100% of Egypt’s population lives in Cairo, Alexandria or elsewhere along the Nile river banks and the Suez Canal.

Alex. (2018, February 23). Population density of Egypt. Vivid Maps. https://vividmaps.com/population-density-egypt/

The capital itself has a population density of 19,376 people per square kilometer (50,180/ sqm), which ranks 37th in the world. It is one of the major regions of the country and some of the most densely populated in the world. The population of Cairo is characterised by its youth. Over 33 per cent of the population of Greater Cairo is under 15 years of age (versus 37.6 per cent nationally). The capial is an example of a third-world megacity, with a population that is growing rapidly due to natural growth despite insufficient services.

70

3.3 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND - DOWNTOWN CAIRO

As the greatest city in Africa and the Middle East and the crossroads of routes to Asia, Europe, and Africa, Cairo is frequently referred to as the “cradle of civilisation.” Although With a history dating back to CE 969, Cairo blends old-world and new-world Egypt.

A number of large-scale initiatives were carried out throughout the 1800s, including the restructuring of the administrative structure, the development of irrigation systems, and the introduction of cotton, a crop that Egypt would soon grow and trade on a significant scale.

Although Cairo’s modern urbanization began in the 1830s, it wasn’t until the years 1863 to 1879 that the city underwent a profound transformation. To the west of the medieval core, Isml commissioned the creation of a city in the European style, influenced by Baron Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris. The design of the neighborhoods of Al-Azbakiyyah (with its vast park), ‘Abdn, and Ismliyyah—all now key areas of modern Cairo— were heavily influenced by French city-planning techniques. These areas were well-developed by the turn of the 20th century, but after Egypt came under British control in 1882, they were turned into a colonial enclave.

Cairo had grown more stratified by the turn of the twenty-first century, with gated enclaves housing the elite classes and extensive sections of informal housing housing the lower and middle classes. Cairo continues to experience many of the same issues that plague other significant developingworld metropolises, particularly the issue of providing transportation and other infrastructural services to its significantly increased population. Nevertheless, Cairo is still one of the most dynamic cities in the world.

71 SETTING THE SCENE

The continuous decline of the quality of the Egyptian public spaces is evident in congested cities such as Cairo. This is identified in commercial streets that mostly function as traffic conduits due to high congestion rather than act as livable spaces that could be comfortably shared by all users.

72

Historical map of Cairo

3.4 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE

The natural environment of Egypt, including its flora and wildlife, had a significant role in the ancient Egyptian economy as well as informing and inspiring the culture’s art, architecture, and religious beliefs. Understanding Egypt’s distinctive ecology and scenery is essential to comprehending its culture and populace.

The Mediterranean Sea provides a natural boundary to the North of the country whilst the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea form part of Egypt’s boundary to the east. The country has six main physical regions: the Nile Valley, the Nile Delta, the Western Desert, the Eastern Desert and the Sinai Peninsula.

Egypt has a relatively dry environment, and the majority of the country’s terrain is made up of vast deserts to the east and west of the Nile River. Only the Nile Valley, the Nile Delta, and isolated desert oasis regions have flora. The infrequent showers can wreak havoc on traffic because the city lacks a surface water drainage infrastructure. It’s common for desert winds to carry dust, especially in the spring, and cleaning up after dust is a neverending effort.

3.5 CULTURAL BACKGROUND

Egypt’s capital city of Cairo has long served as the Middle East’s cultural and media hub. It served as the location of the region’s important religious and cultural institutions for many centuries. It also

73 SETTING THE SCENE

“Cultures and climates differ all over the world, but people are the same. They’ll gather in public if you give them a good place to do it.” -Jan Gehl

encompasses many historical landarks such as Tahrir Square, also known as “Martyr Square”, is a major public town square in downtown Cairo, Egypt. The square has been the location and focus for political demonstrations in Cairo since the early 20th century. After the Egyptian Revolution of 1919, the square became widely known as Tahrir (Liberation) Square. The square was a focal point for the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 and subsequent protests. in 1936, a roundabout with a garden was created at the center of the square. In 2020 the government erected a new monument at the center of Tahrir Square featuring an ancient obelisk from the reign of Ramses II.

Furthermore, in egypt people do not usually frequent streets to enjoy the scenery. Most leisure activities are contrained inside malls and other facilities. The reason the area of Al Shawarby street was chosen as the focus of this paper is to transform the existing mentality regarding the use of public space. It aims to create a pleasant and attractive street that people view as a destination and not just a place of passage.

Al-Shawarbi Street is average 14.7 meters wide and 217 meters long, accommodating buildings with heights varying from 2 to 3 floors and 4 to 5 floors.

The urban space is determined by the ratio between the width of the street and the 3 to 4floors high buildings creating a significant urban enclosure that is naturally illuminated yet not fully shaded. AlShawarbi is mostly occupied by retail businesses at the ground floor level with more than 60 stores distributed along the street which offer various services.

3.6 THE BIRTH OF AL SHAWARBY

74

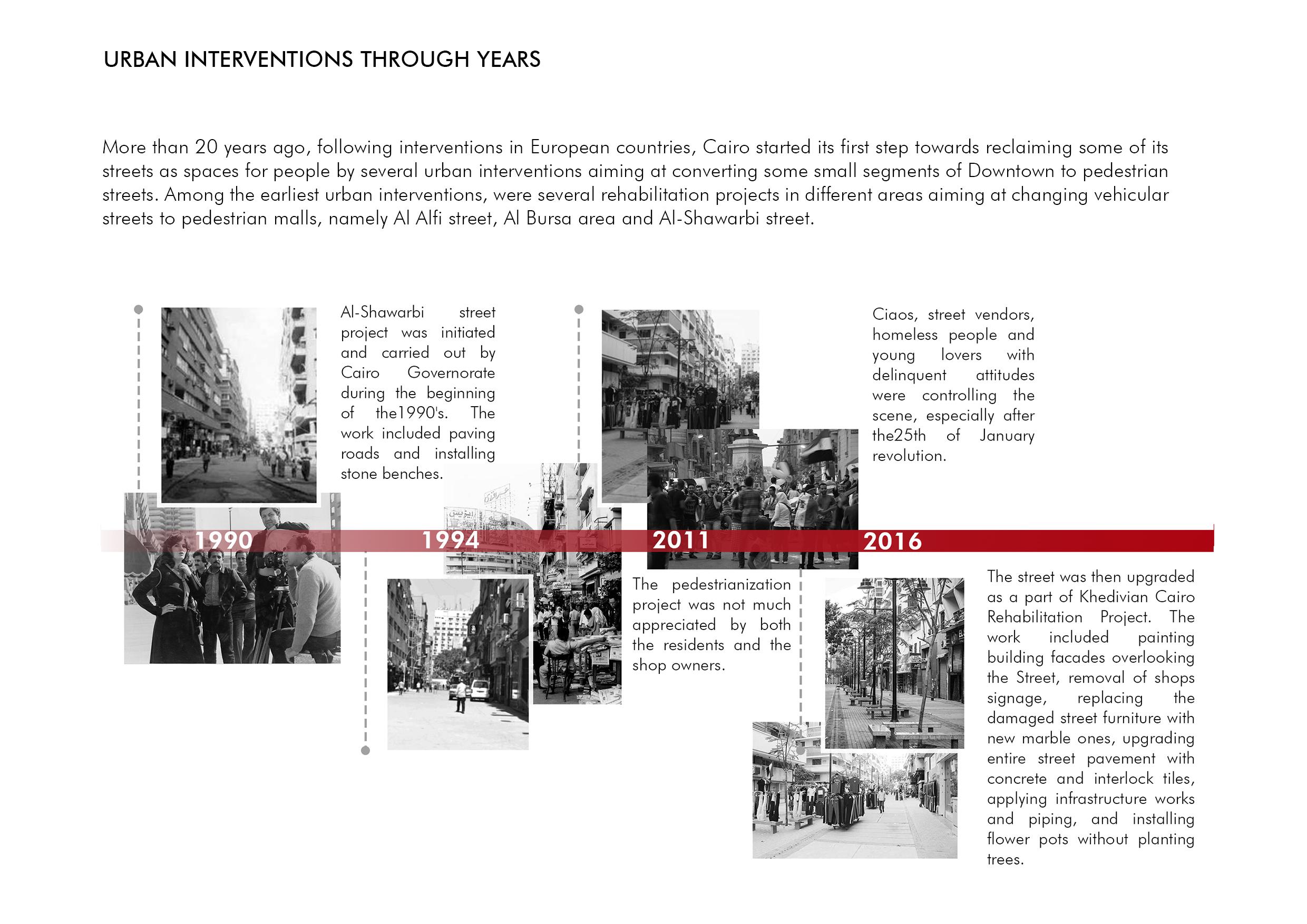

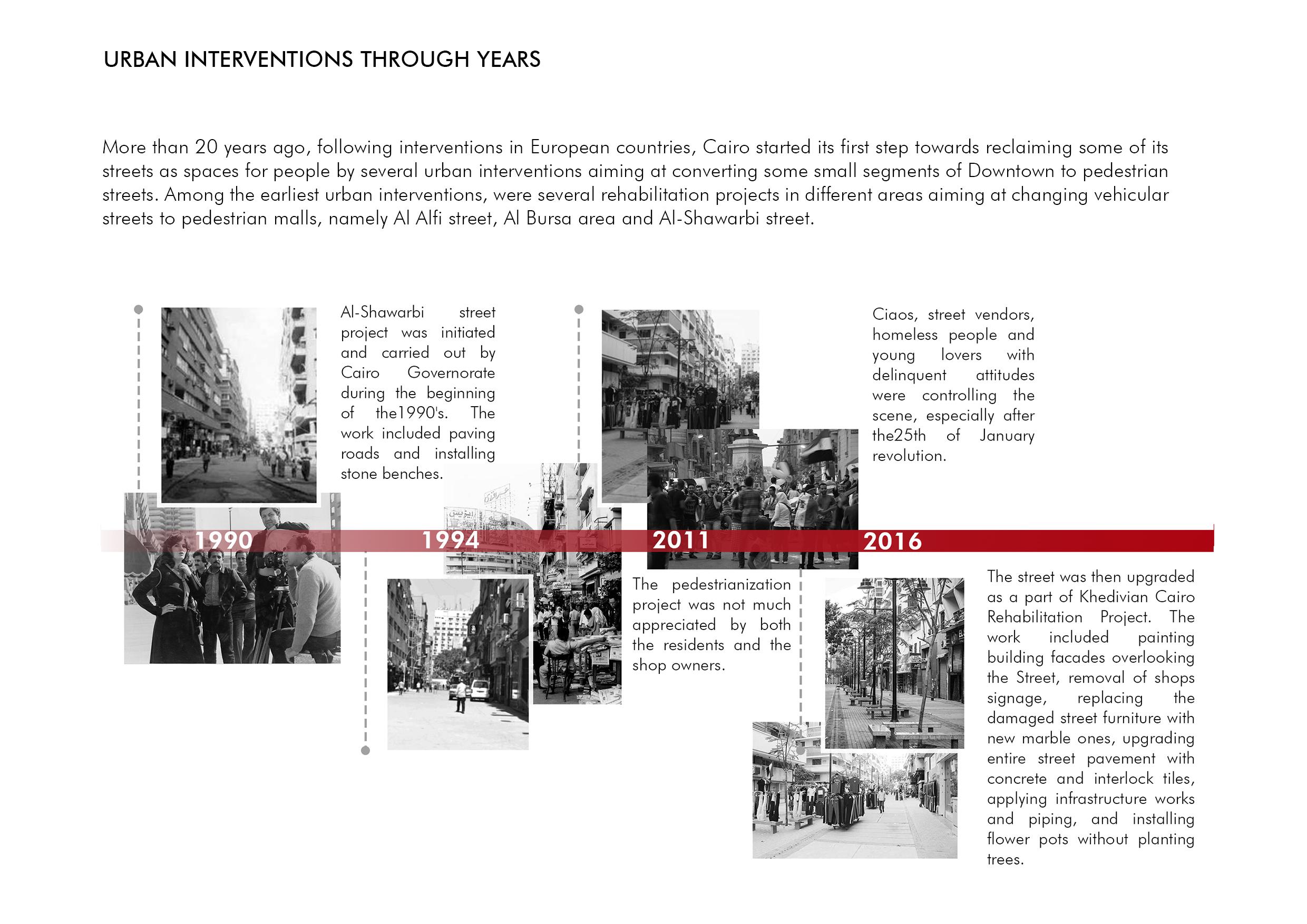

Al-Shawarbi Street used to be a very vibrant street connecting Abd al-Khaliq Tharwat and Qasr al-Nil Streets. In the mid to late 1970s, when Egypt was going through an economic transformation from a state-led economy to an open market policy of Infitah, al-Shawarbi was the only place in Egypt where you could buy exclusive, imported goods. It became a sign of status to buy something from alShawarbi. It remained an icon for quality imported goods until the 1980s, when the general decay of Downtown was underway.

Al-Shawarbi Street was once one of Cairo’s most significant commercial hubs for the sale of contemporary clothing and accessories, and its stores were the first to introduce the fashion of “jeans” to Egypt. It was a popular spot for the wealthy and famous people of the time of beautiful art to shop and keep up with the latest trends. Parisian perfumes could be scented all over it, and in the storefront windows, worldwide brands’ dresses and clothing were showcased. The street, whose status soared and class increased during the 1970s and 1980s, carried the scent of sophistication on his flanks and replicated in all of its splendor the regions of European Cairo in its golden age.

The conditions and features of the street named after a prominent member of the illustrious “Al-Shawarbi” family have altered, and it has become a hub for street merchants. Unlike the pedestrianization of al-Alfi Street and al-Bursa district, which helped revitalize those areas, AlShawarbi Street did not share the same success, possibly due to its single use as a source of cheap clothing. A major fire in 2010 further decreased the street’s status, with 15 shops and 2 company headquarters burnt, and losses estimated at EGP15 million.

75 SETTING THE SCENE

The decision to block the street to cars over twenty years ago, which had a negative impact on the amount of residents’ demand to buy from the street and caused them to turn to other streets open to cars, is blamed by the shop owners for the degradation of the street’s condition. The perspectives of the store owners regarding the existing state of the street and the effects of the decision to restrict vehicular traffic on the flow of buying and selling were observed in this context.

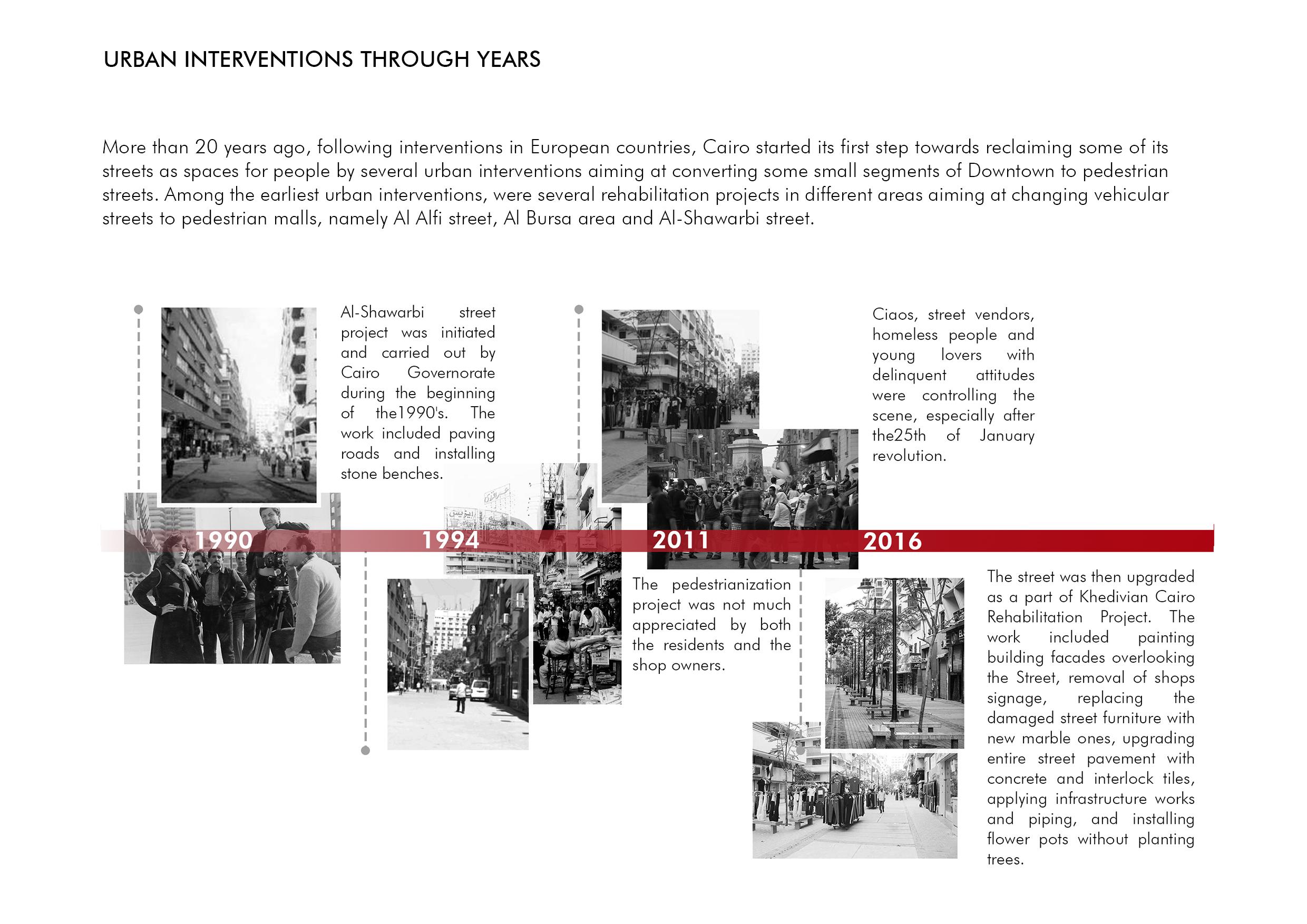

The street was then upgraded in 2016 as a part of Khedivian Cairo Rehabilitation Project. The work included painting building facades overlooking the Street, removal of shops signage, replacing the damaged street furniture with new marble ones, upgrading entire street pavement with concrete and interlock tiles, applying infrastructure works and piping, and installing flower pots without planting trees.

76

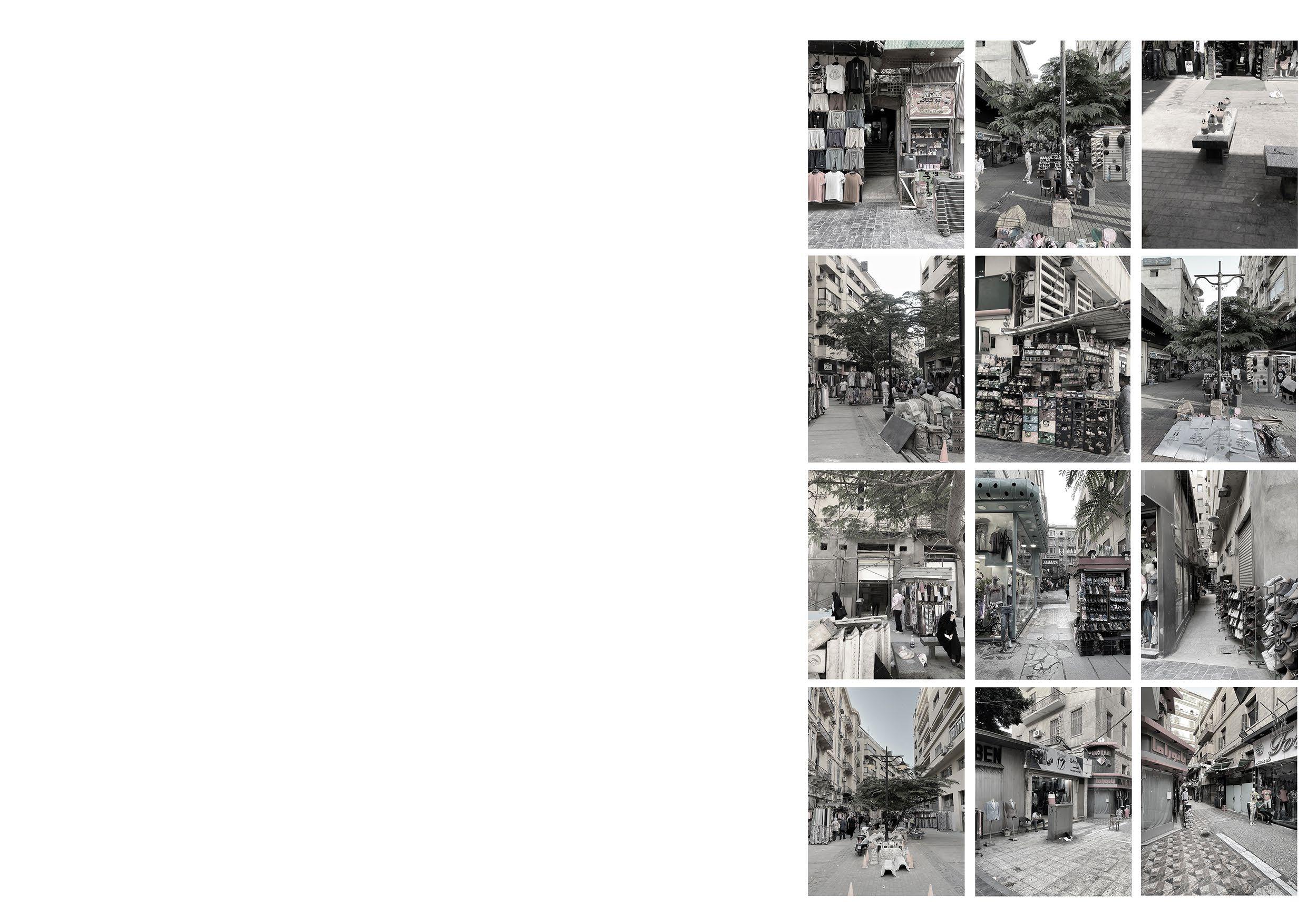

Deterioration of Al Shawarby Identity

77 SETTING THE SCENE

“The 25th Revolution Passed From Here”

3.7 URBAN INTERVENTIONS THROUGH THE YEARS

SETTING THE SCENE

The aim of this thesis is to improve the quality of life for people by improving public spaces using the tools elaborated in the theoretical framework. The strategy followed will reuse and repurpose the existing spaces to create a holictic network of activities. The street will transform based on the various events that could take place.

The area is rich in architectural heritage which will be conserved and respected during the interventions. As the main problem with the site

3.8 NEED FOR REGENERATION

82 1 2 3 4 5 6 INTRODUCTION THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK SETTING THE SCENE DESIGN PROPOSAL CONCLUSION

83 UNPACKING THE SITE 4.1 Macro Scale 4.1.1 Land Use 4.1.2 Road Hierarchy 4.1.3 Figure And Ground 4.1.4 Mental Representation 4.1.5 Attractive Spots 4.1.6 Macro Scale Strategy 4.2 Micro Scale 4.2.1 Al Shawarby Street – Project Focus 4.2.2 Land Use 4.2.3 Shade Analysis 4.2.4 Boundaries 4.2.5 Assessing Walkability 4.2.6 Activity Level 4.2.7 Assessing Street Frontages 4.2.8 Current Situation -Ground Foor Plan 4.2.9 Current Situation - Street Elevation

4.1.1

84

LAND USE

To have a deeper understanding of what the context offer, the area, which is adjacent to the NIle River, contains a mix of services ranging from entertainement, commercial, cultural and administration. It is mainly a residential area with various services at the ground floor level. Al Shawarby is in close proximity to Al Tahrir Square, Talaat Harb Square and Mustafa Kamel Square which are all historical landmarks.

UNDERSTANDING THE URBAN CONTEXT 85

4.1.2

86

ROAD HIERARCHY

The site is accessible by public transport. However the most common means of transportation is private vehicules. Al Shawarby is delimited by two main street with a heavy traffic flow. It is inserted within a pedestrian block that and adjacent to another. The connection between the two walkable areas is severed by the dense vehicular activity.

UNDERSTANDING THE URBAN CONTEXT 87

4.1.3 FIGURE AND GROUND

88

The figure ground analysis highlights the built versus unbuilt areas in the site. It aims to easily pinpoint the spots where interventions can take place.

UNDERSTANDING THE URBAN CONTEXT 89

90

4.1.4 MENTAL REPRESENTATION

Using the five main elements to analyze the site, it becomes apparant that the area has many nodes and a heavy barrier west of the site. Around Al Shawarby, the path are prominent. Understanding the urban fabric further helps in highlighting the barriers and opportunities present in the site.

UNDERSTANDING THE URBAN CONTEXT 91

4.1.5

92

ATTRACTIVE SPOTS

An analysis of the attractive spots in proximity to Al Shawarby was conducted. As the main goal is to encourage and enhance walkability, a 10 minute radius was considered around the site. The area offers a variety of attractions such as palaces, historical monuments, restaurants, museums and more.

UNDERSTANDING THE URBAN CONTEXT 93

4.1.6 MACRO SCALE STRATEGY

94

In order to reconnect and revitalize Al Shawarby and its context, a series of intervention is put into action. The street will be extended onto the main streets which will host a green safety barrier. The link between Al Shawarby and the surrounding pedestrian area will be reinforced. In addition, cycling lanes will be introduced around the blocks surrounding the target area and connecting to the pedestrian priority areas. Furthermore, these piazzas will inclde signs leading visitors to Al Shawarby.

UNDERSTANDING THE URBAN CONTEXT 95

AL SHAWARBY STREET – Project Focus

96

4.2.1

As mentioned previously, the focus area of this thesis will revolve around reclaiming and revitalizing Al Shawarby Street through tactical urbanism.

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS 97

4.2.2 LAND USE 98

Zooming in on the chosen area of focus, the street is ligned with commercial shops and services. It is an area with a high concentration of activity. The context surrounding the street is mainly residential. These shops and other commericial services will create an opportunitiy to engage the locals in the regeneration of Al Shawarby.

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS 99

4.2.3

100

SHADE ANALYSIS

After conducting a shade analysis, it is appearant that the street is mostly shaded. However, some of the pedetrian streets linked to it are fully exposed and do not contain any shading devices making it uncomfortable to walk under the hot mediterranean sun.

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS

101

4.2.4

102

BOUNDARIES

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS 103

4.2.5 ASSESSING WALKABILITY

104

In order to create a holistic network that prioritises pedestrian, it is crucial to look into the street conditions and assess their walkability. The majority of the streets around the focus area are equipped with a sidewalk. However, in some streets, the sidewalk does not offer a safe and comfortable experience for pedestrians. It is either too narrow without any safety barriers, or the pavement itself of the sidewalk needs reperations. In addition to the fact that the site falls in between two main arteries with high car activity and congestion without any safety crossings.

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS 105

- Weekday

/ Display Racks 106

4.2.6 ACTIVITY LEVEL

107

ACTIVITY

/ Display Racks 108

4.2.6

LEVEL - Weekend

109

/ Display Racks 110

4.2.6 ACTIVITY LEVEL - Night

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS 111

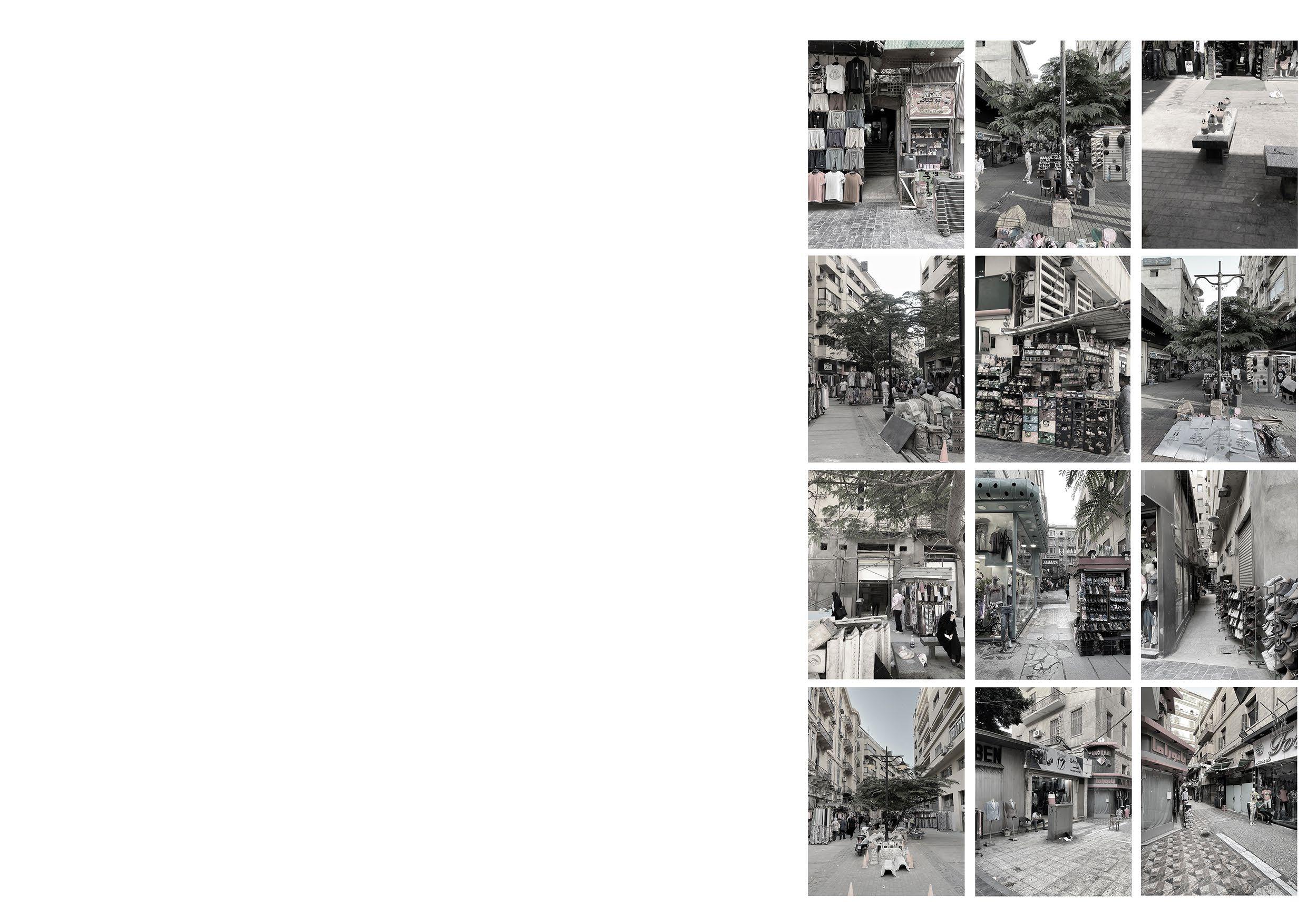

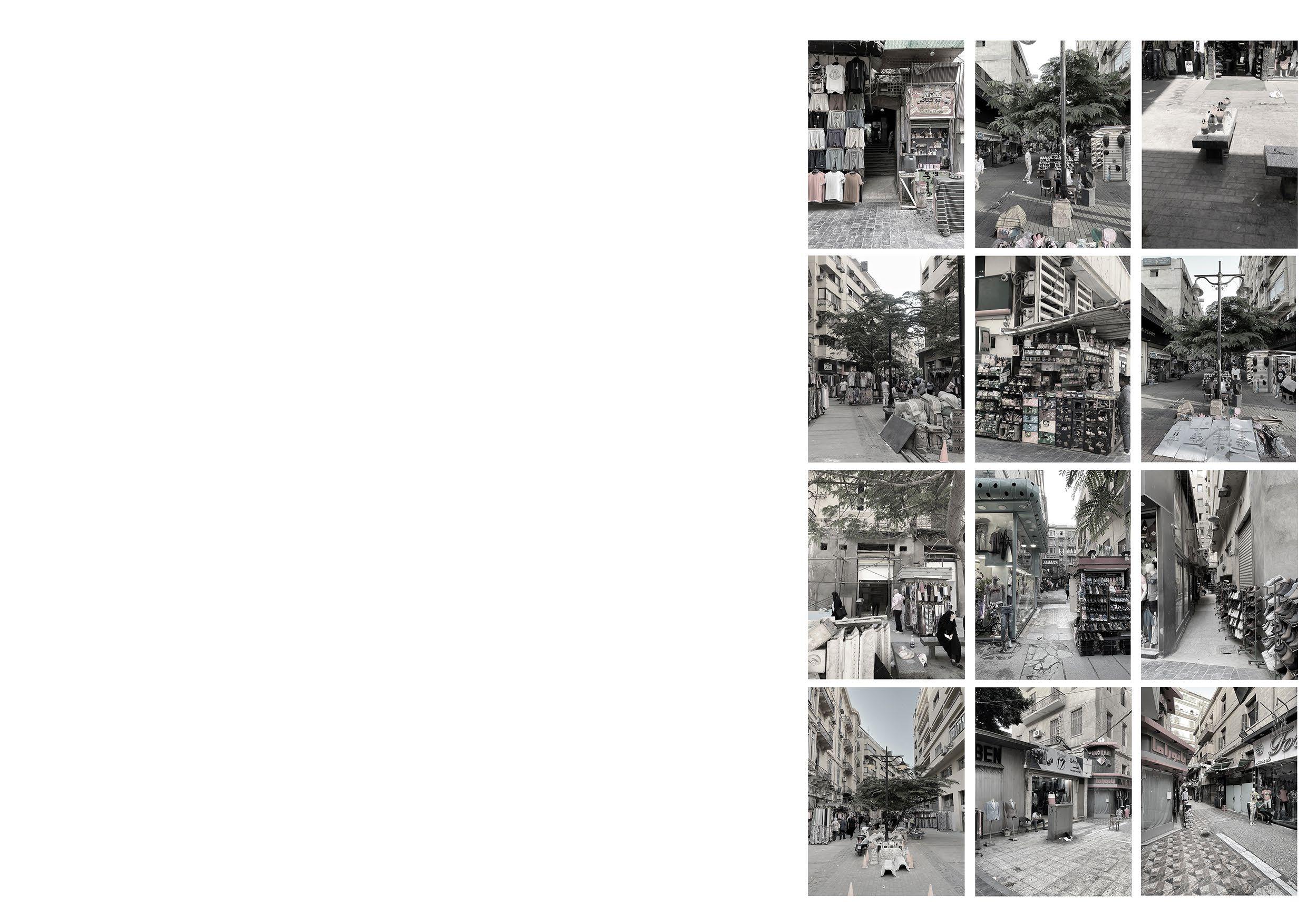

4.2.7 ASSESSING STREET FRONTAGES - Eye Level

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS

4.2.7 ASSESSING STREET FRONTAGES - Eye Level

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS

4.2.8 CURRENT SITUATION - Ground Floor Plan

116

The frontages on the ground level of the street are active but extremely chaotic.

The street in its current state is divided into three lanes with different materials on the side than the center. In addition, the seating and trees are standing in the middle of the street which forces pedestrians to walk on its edges and not properly enjoy the scenery.

In addition, the secondary pedestrian streets leading to and from Al Shawarby are completely neglected and underused.

Finally, based on the shade analysis, the street is missing shading elements to protect people from the sun.

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS 117

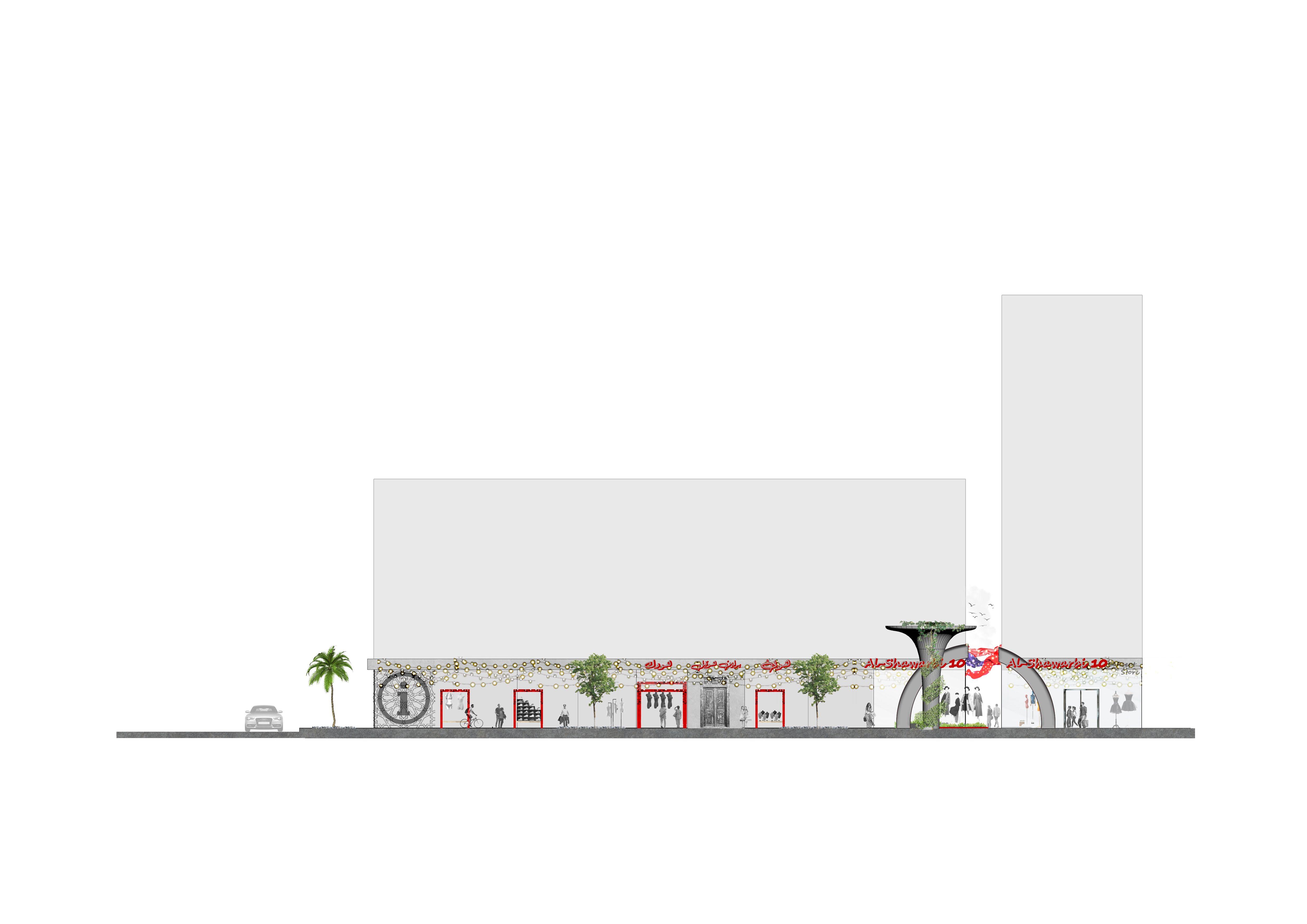

CURRENT SITUATION - Street Elevation

4.2.9

AL SHAWARBY STREET ANALYSIS

120 1 2 3 4 5 6 INTRODUCTION THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK SETTING THE SCENE UNPACKING THE SITE CONCLUSION

121 DESIGN PROPOSAL: THE REBIRTH OF AL SHAWARBY 5.1 Potentials & problems of the site 5.2 Strategy and actions in the street 5.3 Abacus of possible and selected elements of design 5.4 Proposed design elements 5.5 Intervention masterplan 5.6 Intervention masterplan - ground floor 5.7 Events calendar 5.8 Proposed elevations 5.9 Proposed sections 5.10 Actions for reclaimed public space 5.11 Scenes

DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.2 STRATEGY AND ACTIONS IN THE STREET

Accessing the street

Highlighting the building entrances

Removal of existing flooring and seating, moving the trees

Adding pavement layer

124

Converting some functions into more necesaary functions

Preserving the heritage and renovation of ground floor frontages

Introducing the street interventions

Carefully positioning the trees respecting the flexibility of the space

125 DESIGN PROPOSAL

126

My project is oriented to renovate and change through constant selection of different elements of a huge variety over time

127 DESIGN PROPOSAL

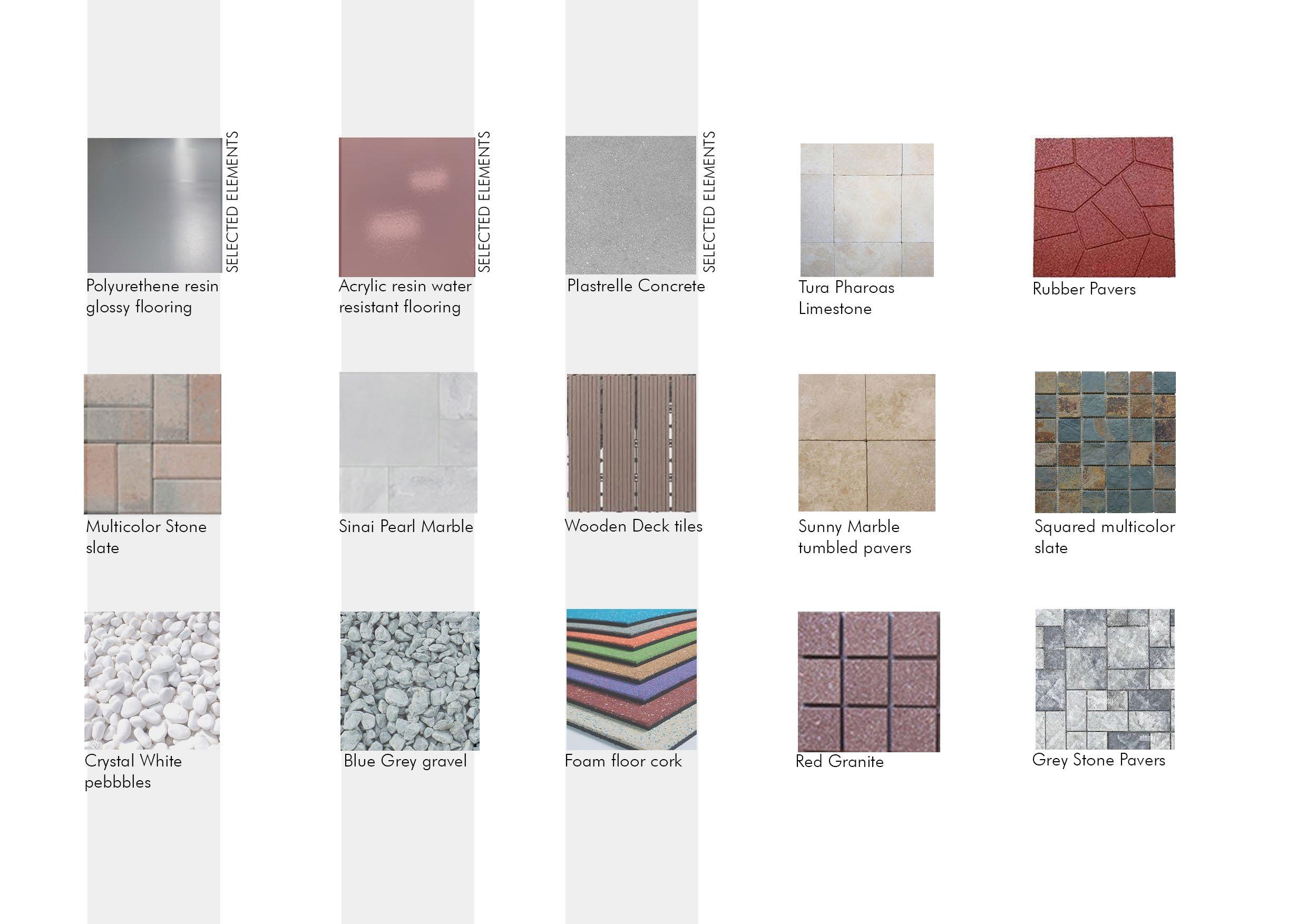

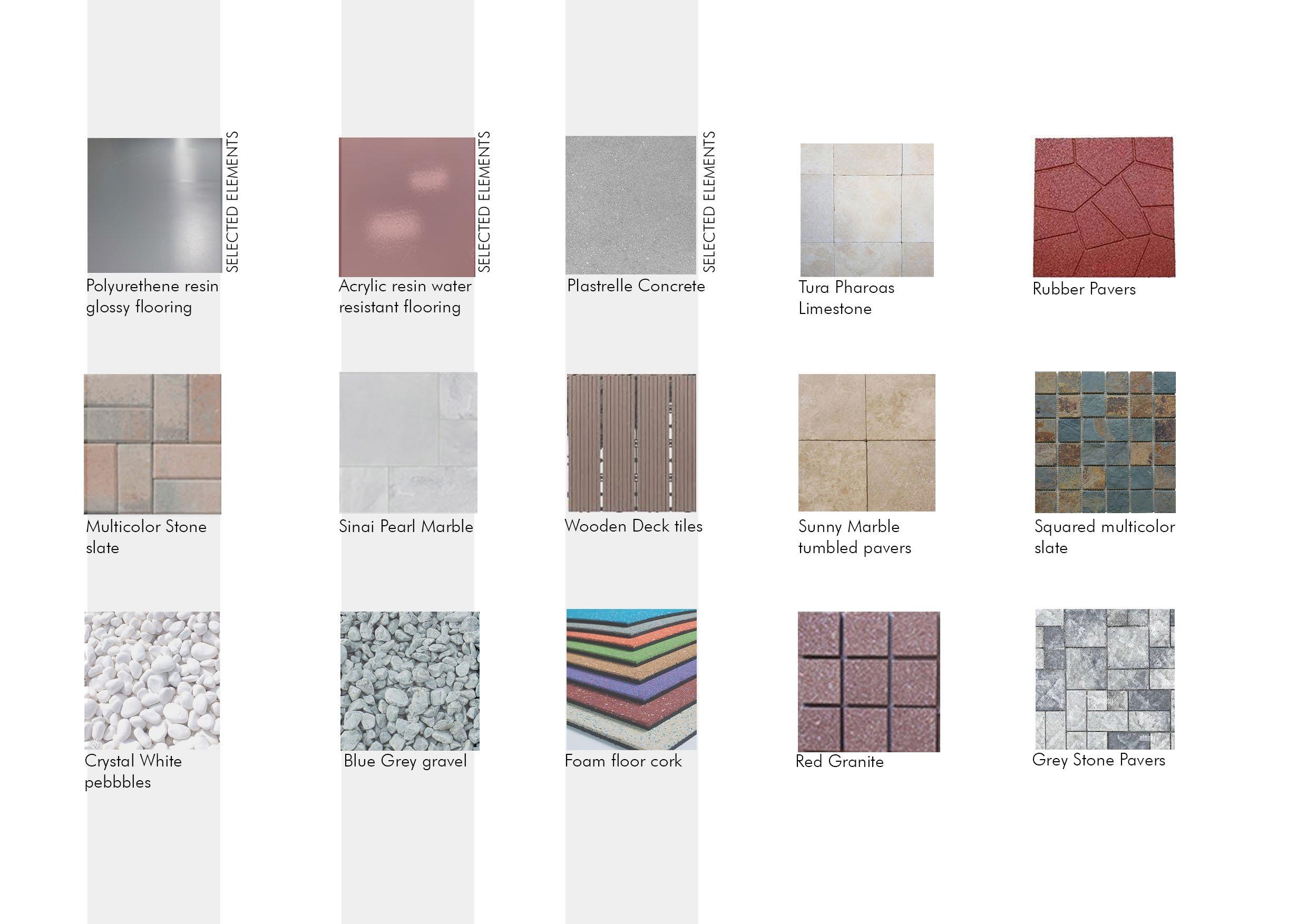

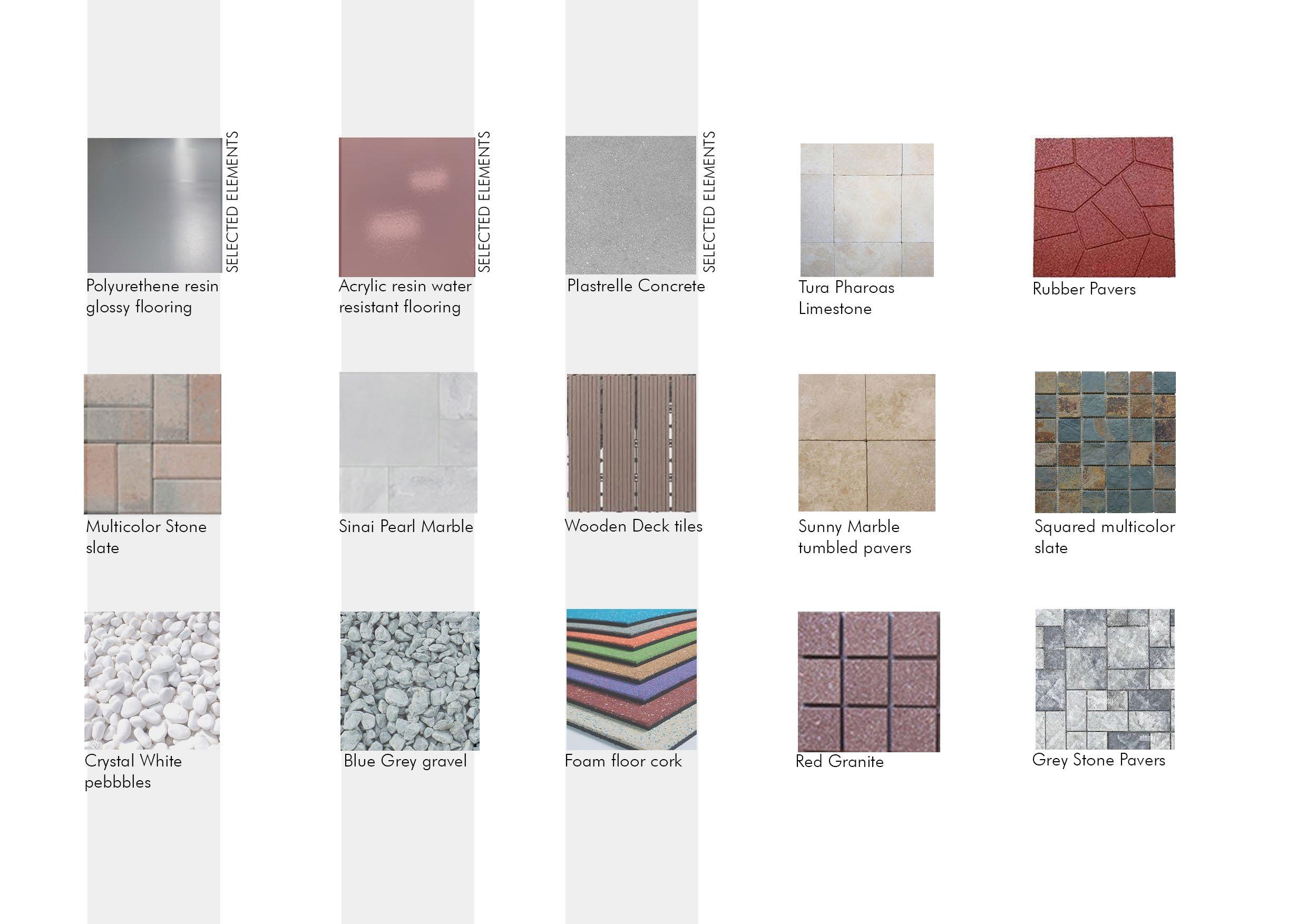

5.3 ABACUS OF POSSIBLE AND SELECTED ELEMENTS OF

128

DESIGN

129 DESIGN PROPOSAL

DESIGN - Vegetation

5.3 ABACUS OF POSSIBLE AND SELECTED ELEMENTS OF DESIGN

130

DESIGN - Materials 131 DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.3 ABACUS OF POSSIBLE AND SELECTED ELEMENTS OF DESIGN

132

133 DESIGN - Structures DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.4 PROPOSED DESIGN ELEMENTS - PATTERN

Abdullatif, K. (2022, April 24). This Timeless Tiles Collection Echo Ancient Egyptian Designs. SceneHome. https://scenehome.com/Projects/This-Timeless-Tiles-Collection-Echo-Ancient-Egyptian-Designs

DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.4 PROPOSED DESIGN ELEMENTS - FRAMES

Owen, J. (2008). The Grammar of Ornament: a Visual Reference of Form and Color in Architecture and the Decorative Arts. A & C Black.

Owen, J. (2008). The Grammar of Ornament: a Visual Reference of Form and Color in Architecture and the Decorative Arts. A & C Black.

Detail of fixation of wooden seat to metal frame

Detail of pattern

DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.4 PROPOSED DESIGN ELEMENTS - FRAMES

DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.4 PROPOSED DESIGN ELEMENTS - FRAMES

DESIGN PROPOSAL

A Street You Go To Not Just Through

142

143

A Destination For All

5.5 INTERVENTION MASTERPLAN LEGEND 1- Al Shawarbi Street 2- Pedestrian Streets 3- Downtown Squares Green Corridor Cycling Lanes 2 2 2 3 3

DESIGN PROPOSAL 1 2 2 3

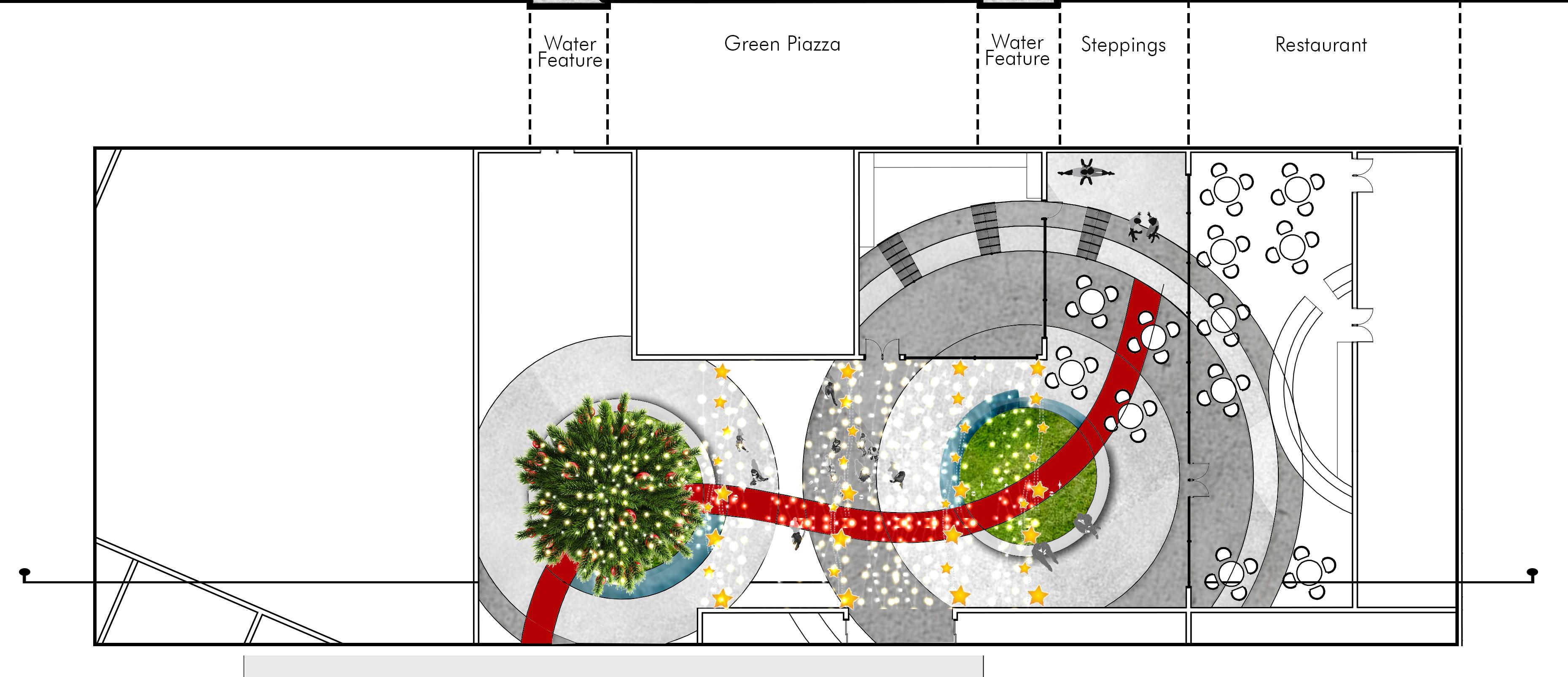

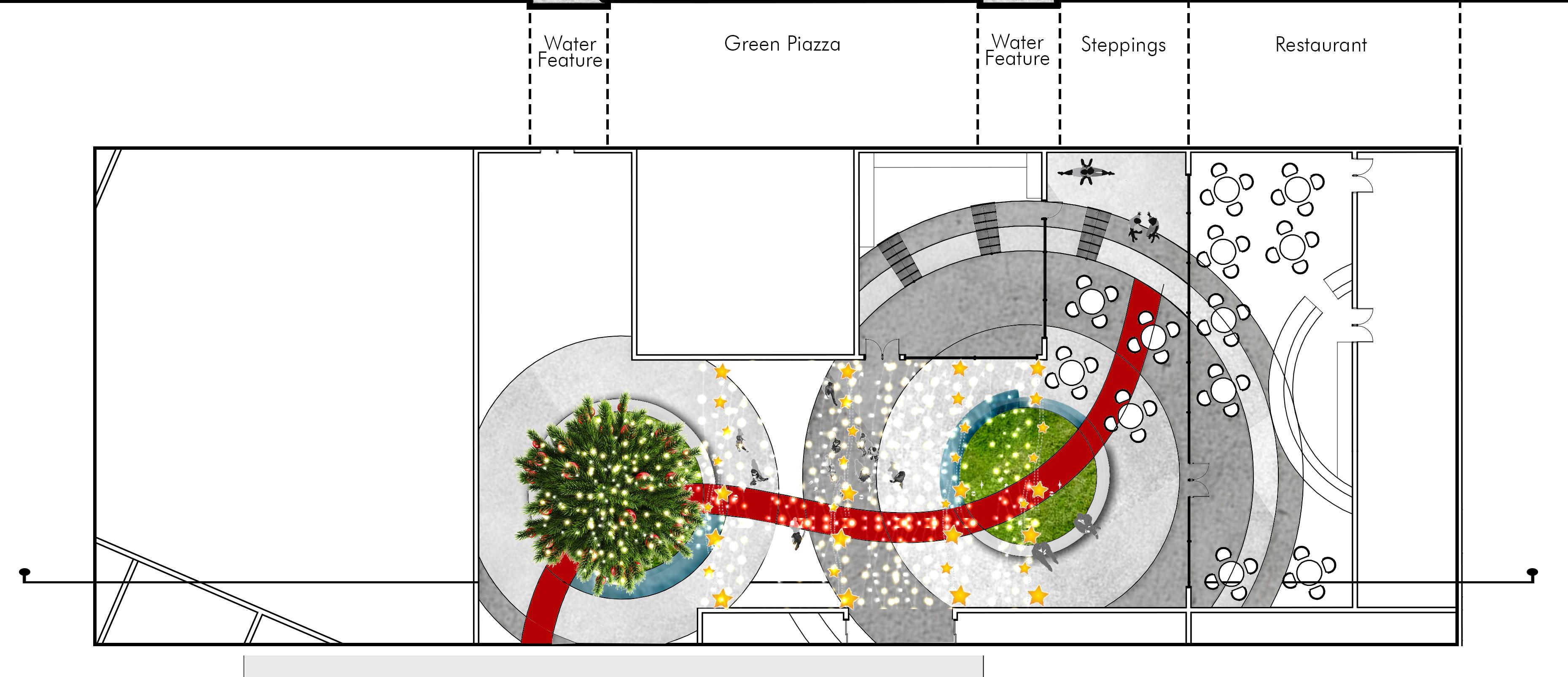

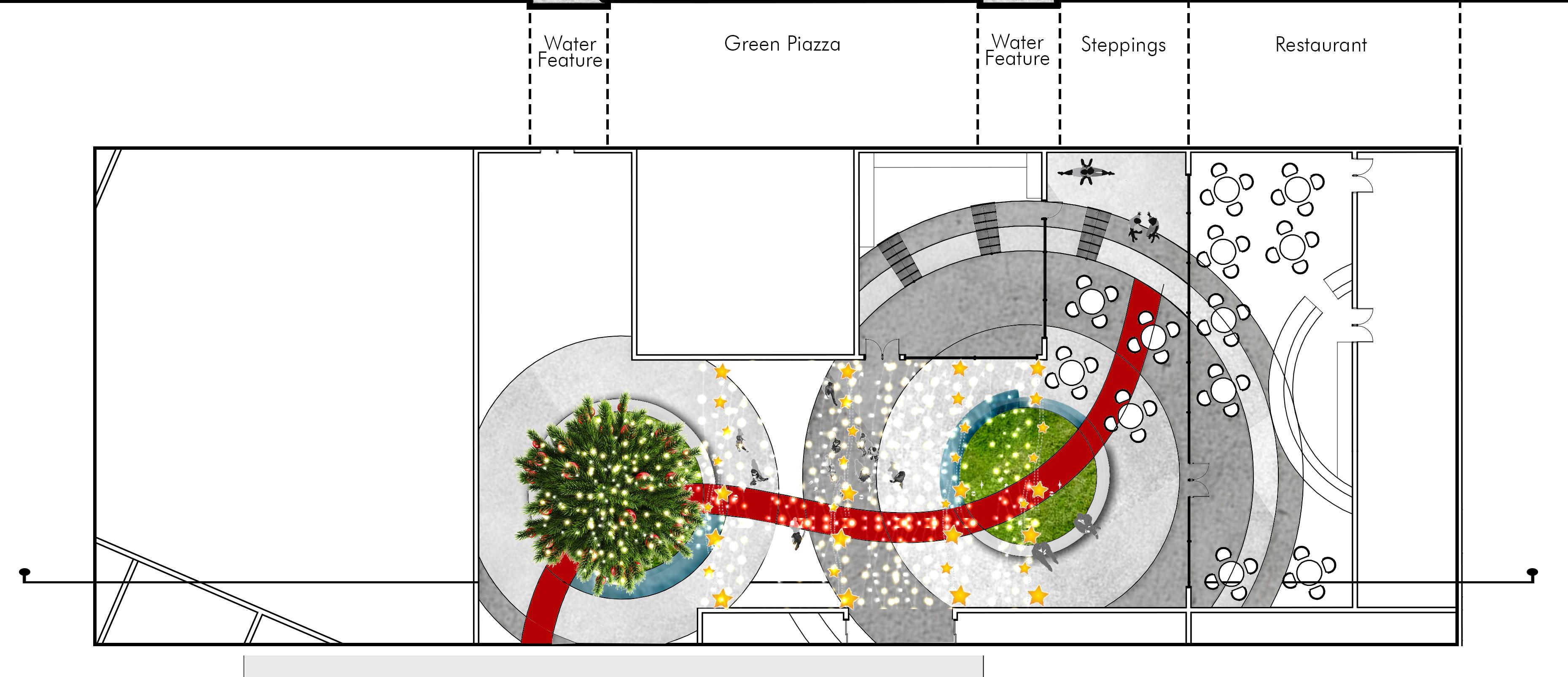

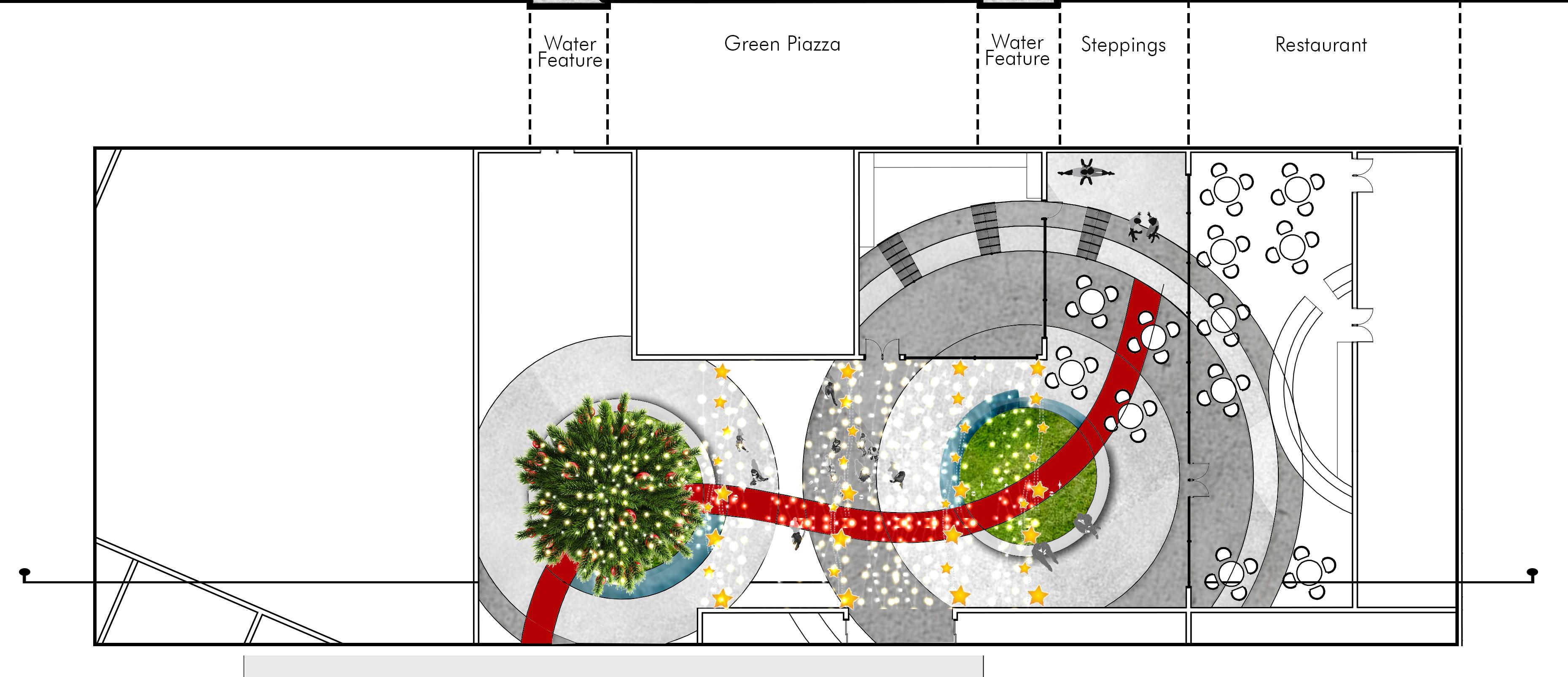

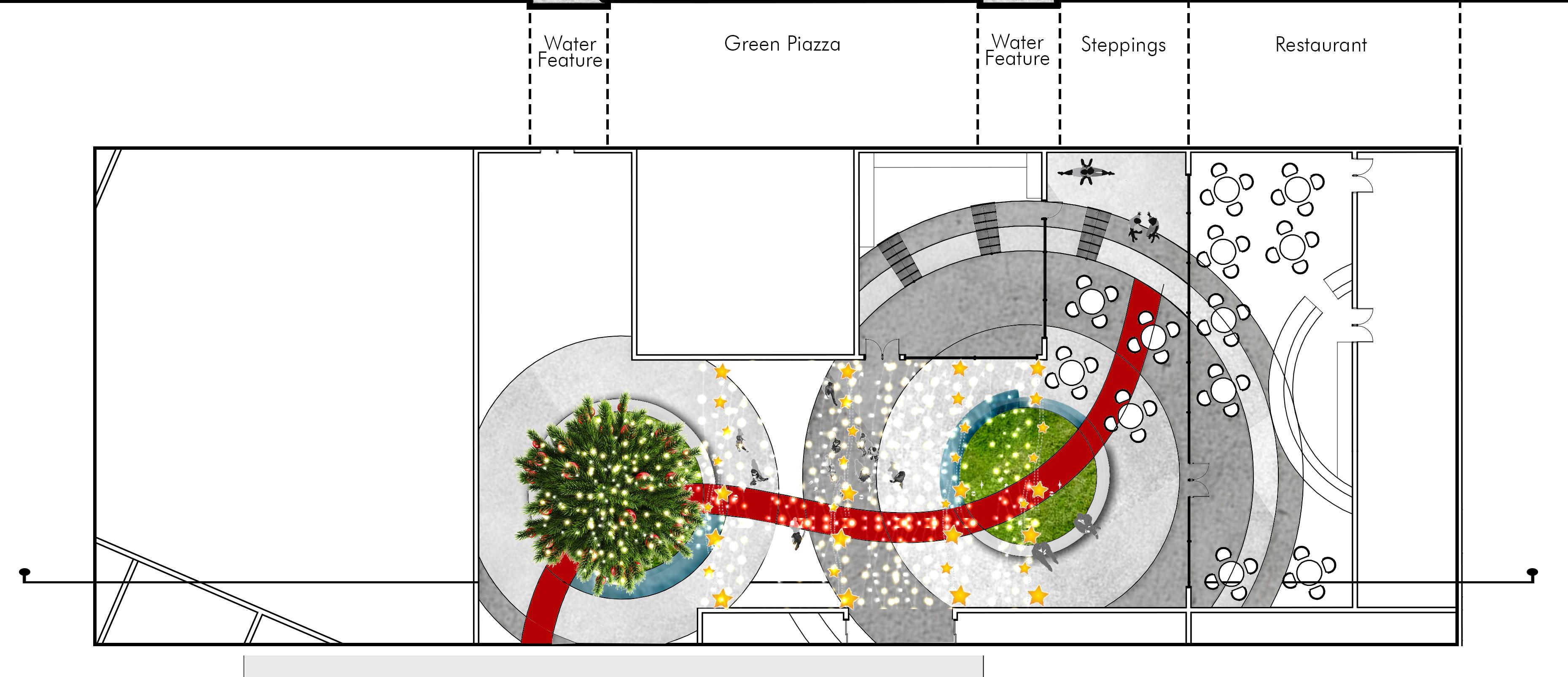

INTERVENTION MASTERPLAN - GROUND

LEGEND

1- Entrance

2- Info Point

3.1- Concept Store Chain - Art Exhibition

3.2- Concept Store Chain - Clothing Store

3.3- Concept Store Chain- Restaurant

3.4- Concept Store Chain - Library

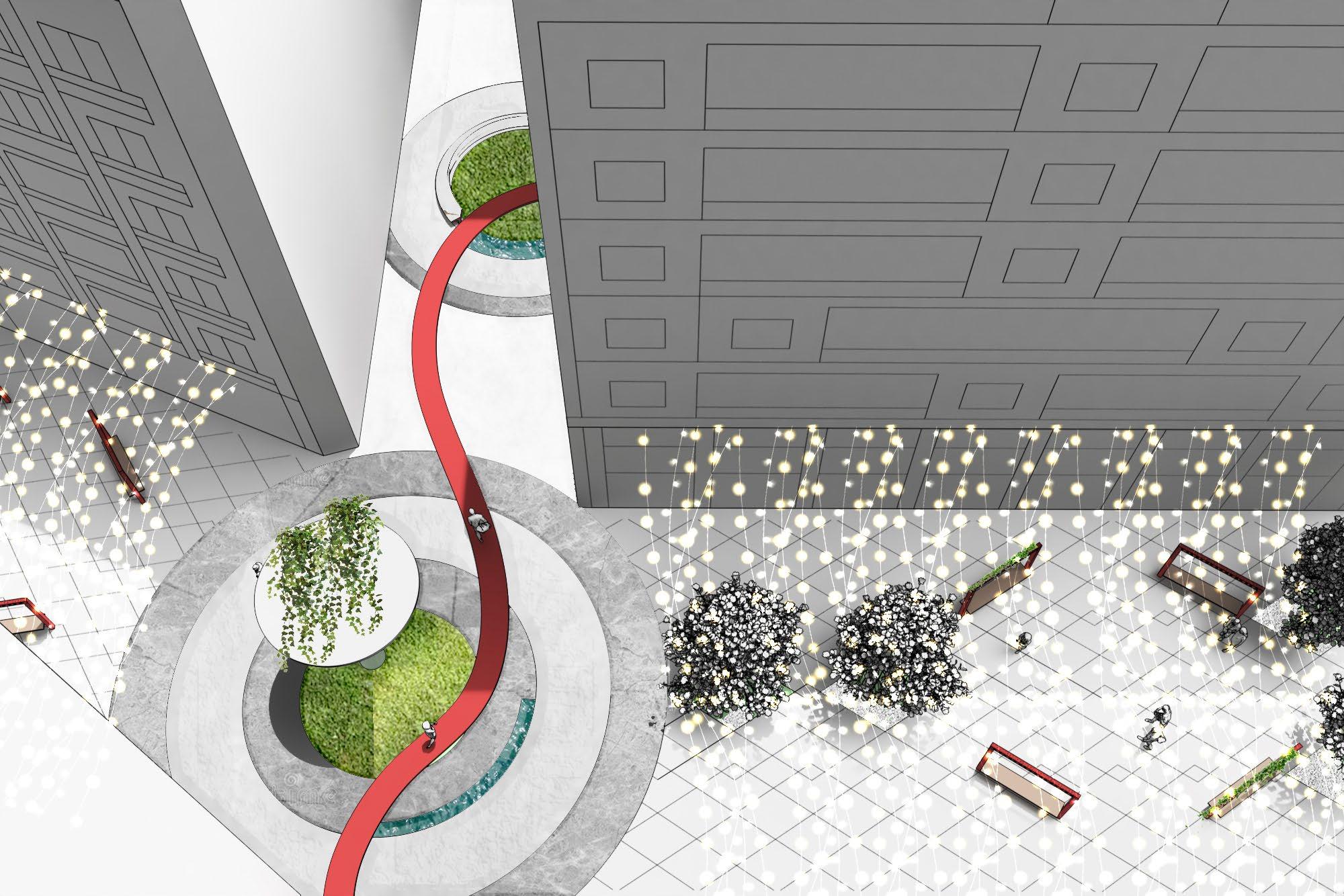

4- Green Piazza

5- Walk of Fame 6- Storage 7- Bathrooms 8- Kids Playground 9- Light Exhibition 10- Art Workshop for People 11- Bar & Cafe

146 5.6

FLOOR

1 2 2 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 4 5 6 6 6 7 7 8 9 10 11 1 11

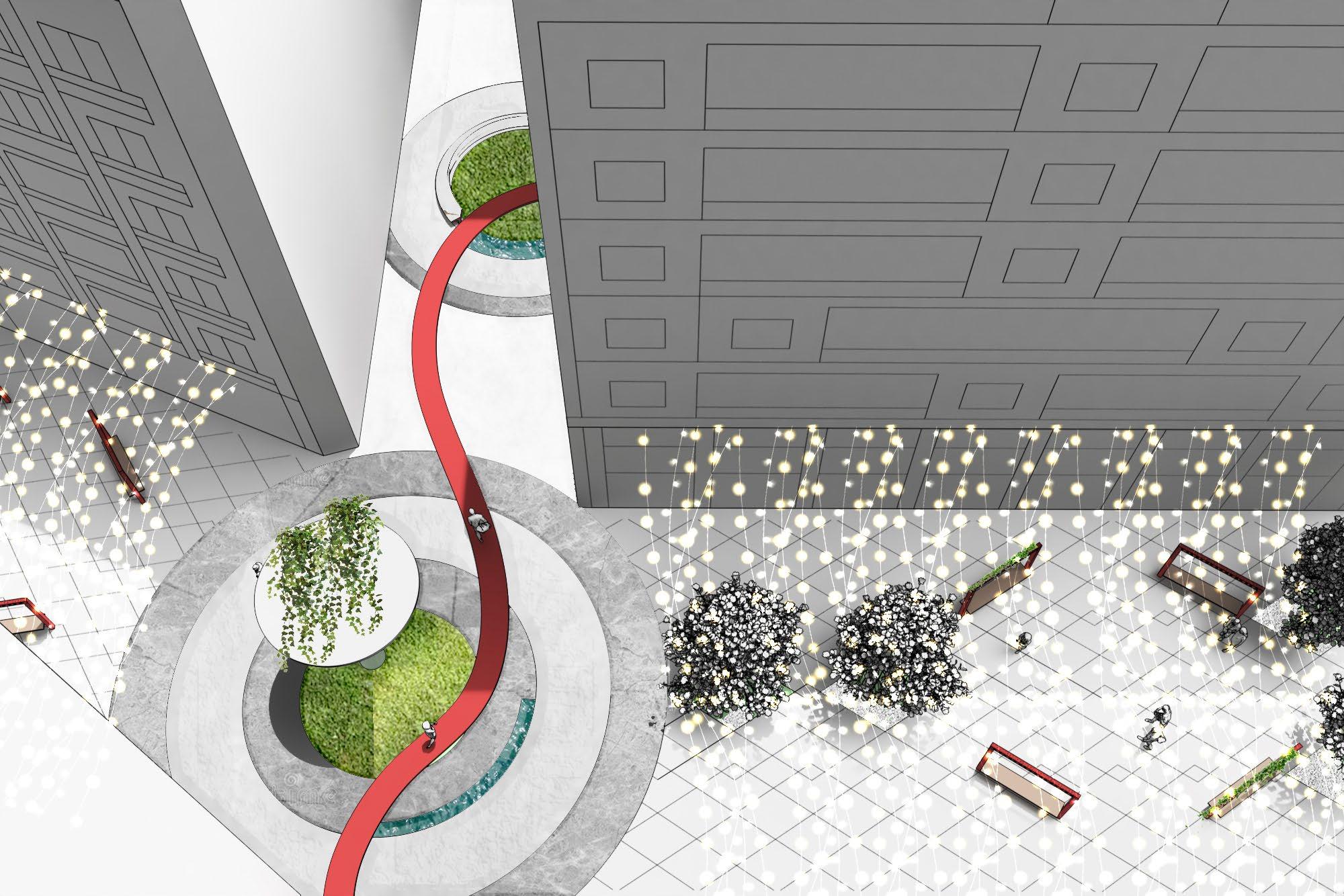

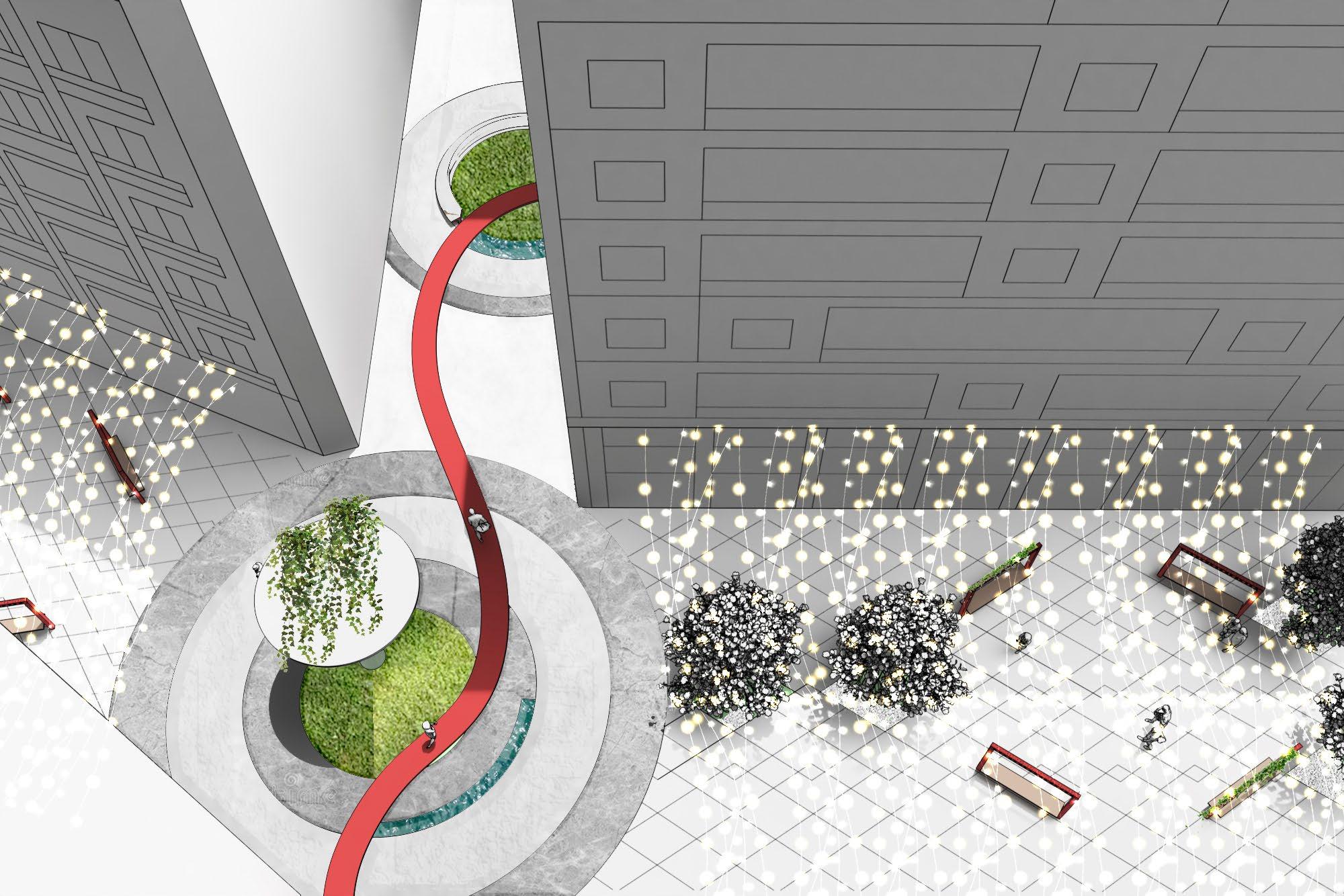

AERIAL VIEW

5.7

EVENTS CALENDAR

DESIGN PROPOSAL

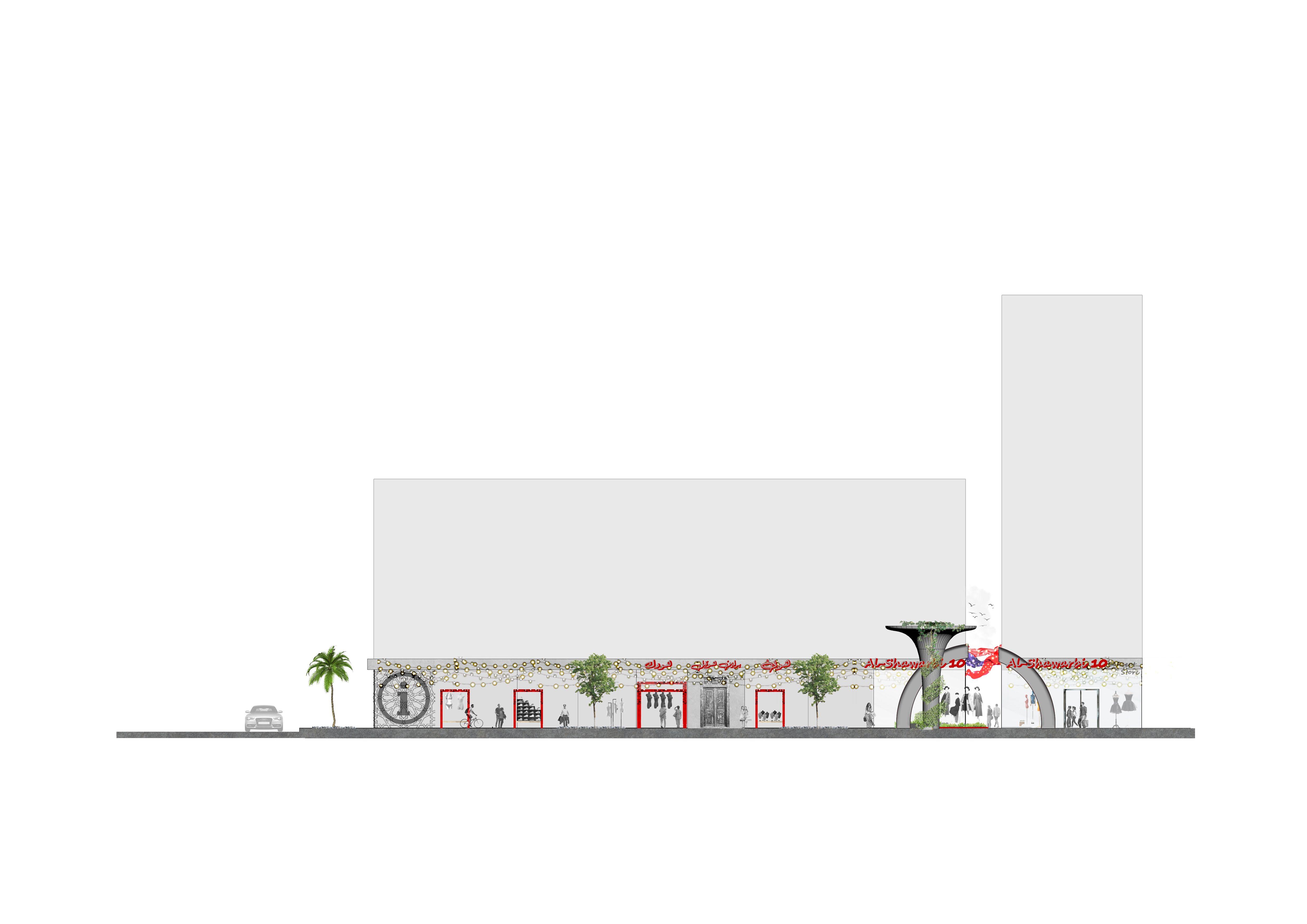

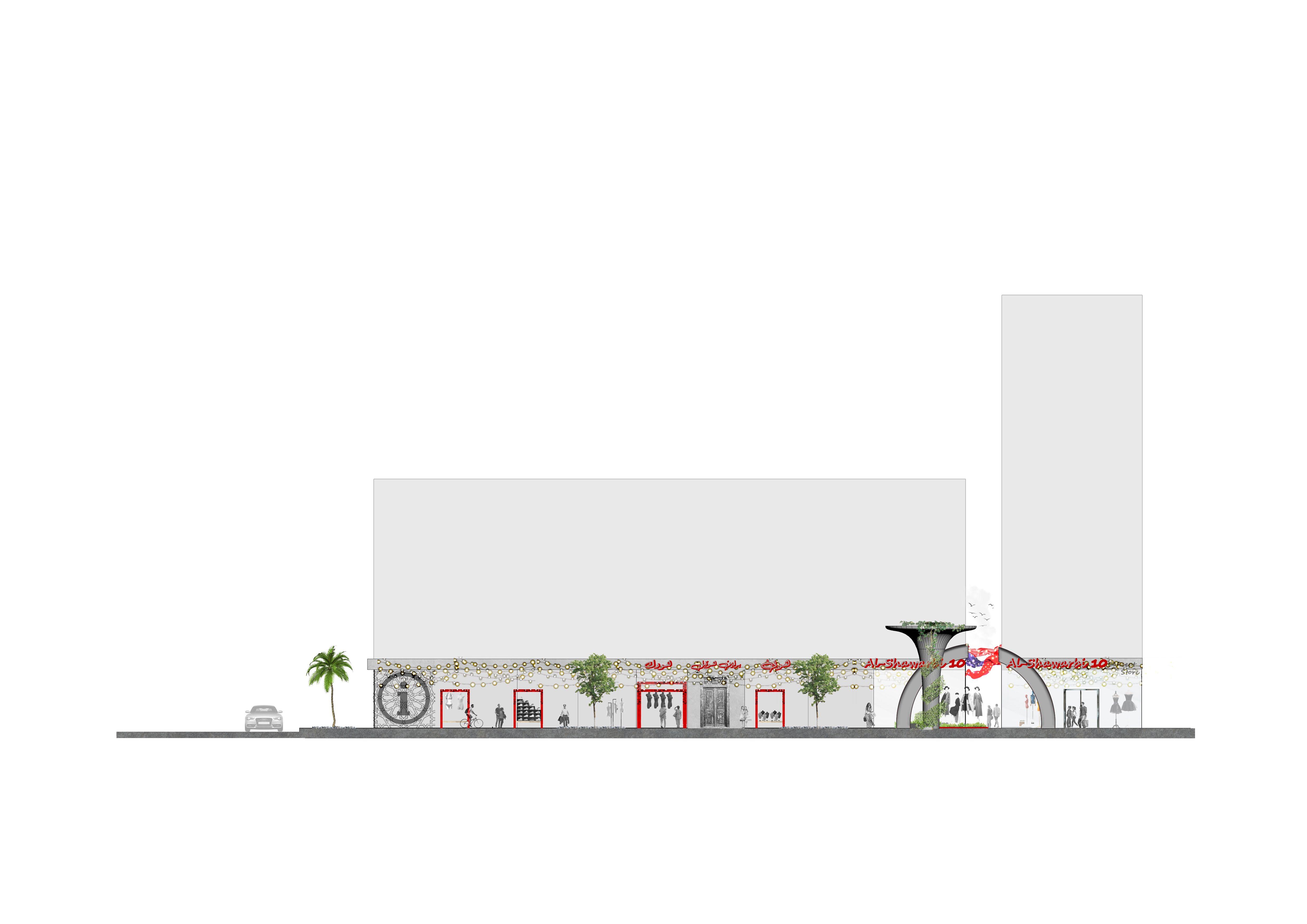

5.8 PROPOSED ELEVATIONS

Existing

Elevation Proposed Elevation

DESIGN PROPOSAL

PROPOSED ELEVATIONS

154

5.8

Existing Elevation

Proposed Elevation

155 DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.9 PROPOSED SECTIONS

159 DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.9 PROPOSED SECTIONS

DESIGN PROPOSAL During Christmas Festivities 1/200

5.9 PROPOSED SECTIONS

On an Average Day 1/200

166 1/200

A city’s environement is shaped not only by the people who have an important influence, but by everyone who lives or works there.

- Robert Cowan

167 DESIGN PROPOSAL

SCENES

5.10

DESIGN PROPOSAL

SCENES

5.10

DESIGN PROPOSAL

SCENES

5.10

DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.10 SCENES 174

DESIGN PROPOSAL 175

SCENES

5.10

DESIGN PROPOSAL

SCENES

5.10

DESIGN PROPOSAL

SCENES

5.10

DESIGN PROPOSAL

5.10 SCENES

DESIGN PROPOSAL

SCENES

5.10

DESIGN PROPOSAL

186 1 2 3 4 5 6 INTRODUCTION THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK SETTING THE SCENE UNPACKING THE SITE DESIGN PROPOSAL

CONCLUSION

187

Usually, cities are planned with a top-down approach, which often disregards and overlooks the comfort of pedestrians. This results in highly congested cities that do not consider the human scale. To tackle this issue, governments have started taking actions to adjust city planning and regenerate the streets. However, the procedure takes into consideration many political and economical factors which can make it extremely lengthy. With the rise of the tactical urbanism movement, people have started taking matters into their own hands and implementing short-term, low-cost actions to better their neighborhoods. Based on the case studies and research listed in this paper, tactical urbanism is a very effective wat to create and design public space.