13 minute read

Mike Inez: The Music Is Always Around You

By Freddy Villano

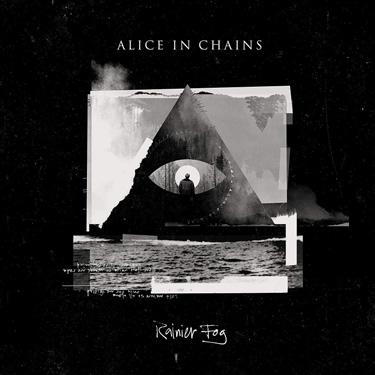

Mike Inez is in the home stretch of Alice In Chains’ 2019 co-headlining tour with nü-metal juggernauts Korn. It’s been a year since the release of AIC’s sixth studio album, Rainier Fog, and Inez and his cohorts — Jerry Cantrell (guitar/ vocals), William DuVall (vocals/guitar), and Sean Kinney (drums) — have been touring almost nonstop ever since. “It’s been a really good tour,” he surmises. “We’ve just been all over this damn planet.” Indeed they have, hitting places like Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Athens for the first time, as well as countries like Estonia. But it’s also been a transformative kind of tour, according to Inez, who lost his grandmother recently. “We had births and deaths on this tour,” he concedes, noting that reality intervenes on musicians’ touring lives. He’s not complaining, though; he’s sim- ply reflecting on being a musician, or a “pirate,” as the AIC crew sometimes like to refer to themselves. Inez was plucked from relative obscurity by Ozzy Osbourne in 1990 and has gone on to play with Heart, Slash’s Snakepit, and, of course, Alice In Chains. He’s lucky and he knows it.

Advertisement

But he’s also got the skill set to sustain those strokes of luck. His playing in AIC over the years is compelling yet understated, characterized by gritty, muscular tone and a melodic sensibility that helps to elevate the band’s material beyond typical rock and metal fare. This style was immediately apparent on his debut EP with the band, Jar of Flies [1994, Columbia], particularly the single “No Excuses” and songs like “Heaven Beside You” from AIC’s self-titled 1995 release. Both albums were also milestones for the band, in that each debuted at #1 on the Billboard 200, with the EP spawning the band’s first #1 single on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock chart.

Upon regrouping a decade after the death of original lead vocalist Layne Staley, AIC seemed to reignite its momentum, hitting a new stride with William DuVall on vocals and releasing Black Gives Way to Blue [2009, Virgin/EMI] and The Devil Put Dinosaurs Here [2013, Capitol]. These albums served not only to solidify Inez’s role within the band, but also to affirm that Jerry Cantrell continues to be the songwriting leader holding the secrets to the AIC sound. Last year, AIC released Rainier Fog, which saw them return to their Seattle hometown to record for the first time in 20 years. Whether he’s grinding away under riff-oriented tunes like “So Far Under” or “Drone,” or providing the sub-hooks on the mellower “Fly” and “Maybe,” Inez’s bass lines have become the fulcrum on which the rest of the band pivots. Lately, Mike has been reflecting on the state of the music industry. “There’s so little value on music these days. It makes everybody small. Every band now, you can look up on your phone and it’s the same exact font. It puts everybody on a weird, even playing field. But it’s bullshit. We were in that era of MTV, and it was such a special time and we didn’t even know how great it was, you know? We thought, ‘Oh, we’ll always sell CDs and there will always be Tower Records.’ Even the shopping malls are empty now.”

We talked to Inez at Jones Beach Amphitheater on Long Island, New York, where he was happy to discuss his life on and off the road, his newly designed Fishman pickups, his practice regimens, and his infectious, upbeat outlook on life.

A year after releasing Rainier Fog, and with nonstop touring under your belt, has your relationship to the album changed?

It has. There’s that old Joan Jett quote — I think she said that you record an album and go play it for a couple of years, and then by the time you get back home, you’re playing it the way you should have played it [laughs]. But I think our producer is great. It was our third record with Nick Raskulinecz, and we’ve learned to really trust him in the studio. They’re all kind of hard records to make. Records are hard.

What’s hard about it?

Each one, you go in with expectations, but it grows on its own, just like a child that has its own personality, and all the band guys will be in a different spot, good or bad.

Did anything change about the tunes when you started playing them live?

There are so many layers on the record, so live, we have to cheat — like, I’ll play guitar parts on bass in certain parts to fill in some spots. We work as a ball team. We’re really a good ball team; we’ve always got each other’s backs. We’re playing so good right now. I’m just really proud of our band.

When you say guitar parts on bass, are you talking chords, harmonies?

Some chordal stuff. Usually, on the song “Red Giant,” I switch to a guitar part. Like, when Jerry goes into a lead, I bring it up a 3rd and play some of his harmony parts. And William fills in a lot, too. It’s cool, because it happens kind of naturally. I’ll just do it and Jerry will go, “Oh, that’s good — do that.” Or, Jerry will ask William to do something, and William is super-fast at learning.

Are you playing a lot of new material on the Korn tour?

We’re playing “The One You Know” every night, and the title track, “Rainier Fog.” It’s kind of hard on this particular tour … I think we’ve got only 75 minutes to play, so we have to play the six songs everybody wants to hear: “Would,” “Man in the Box,” “Rooster,” and all that. We try to rotate as much as possible every night. I guess it’s a good blessing to have so many songs, but then you don’t get to play them all, and that kind of sucks, too. But I guess it’s like having extra gloves in your bag.

Do you think having a background in saxophone and clarinet enables you to pick up on guitar parts or more melodic counterpoint with your bass playing?

I don’t know what it is. When I joined Ozzy’s band, learning Geezer Butler’s lines and especially Bob Daisley’s lines … Bob had such a great sense of melody and parts, so I went to the “University of Ozzy Osbourne.” [Guitarist] Zakk Wylde and I would always say that. There’s only a handful of guys in the world who get to say they did that, and Zakk and I always approached it in the right way. We really appreciated it and worked really hard for Ozzy and tried to do our best for him. Then, playing with Heart, too — learning those bass parts really made me a better bass player.

You’ve been blessed to jam with some cool people.

Chemistry is so important, too. I was reminded of this last night, watching the Rolling Stones. They were sloppy, but “cool” sloppy, and nobody sounds like that. Was Darryl Jones playing bass? Yes! Before the show, their security guy, Chubbs, brought me and Sean onstage. Darryl had a couple of ’69 classic Ampeg heads up there and two 8x10 cabinets. It was just so beautiful.

What are you using live on the Korn tour?

The only amps I have onstage are two wedges on each side, the 2x10 Ampeg wedges with an SVT-IIPro [head] from the ’90s. The only real difference I got going on now is I’m using Fishman Fluence pickups. We’ve got a signature pickup line coming out, and I was their guinea pig. Frank Falbo, who used to work at Seymour Duncan, had this idea, and Larry Fishman gave him the green light to do it. So, they took my [Warwick Streamer Stage I] moonburst bass, which we found out had fake EMG pickups from the ’90s in it. A guy in Germany, who has passed away, was making them. I was always trying to match that tone, and I could never match it. It was just so growly and present, and it’s got all these harmonic overtones. Even when you’re sliding, or if you hit a harmonic by accident, it’s always musical — it’s such a musical bass. It’s my favorite bass. Ozzy bought it for me in 1990, and we put in new pickups in ’93 on a tour in Europe. They were the fake ones, so I could never match that tone [on other basses]. So, Fishman put my bass in this MRI-like machine that shows the magnetic throw off the pickups. It’s crazy. I’ve got seven prototypes, so I’ve been using those on this tour. That’s one of the good things about digital technology now [laughs]. It’s a weird world, isn’t it?

Earlier, you were lamenting about what technology has done to the music industry. Is there anything else good to come from it?

YouTube is great. I wish I’d had YouTube when I was coming up as a kid. I could have put on an instructional video and sat there for hours. It would have been a great tool.

Did you get to check out the Fishman pickups before going on tour?

I went into a studio in L.A., Dave Bianco’s old studio [Dave’s Studio, formerly known as Mama Jo’s], and Paul Figueroa, our second engineer, went with me. It was a two-year process, from getting the bass scanned, and then going into the studio, where they had this old P-Bass where they could just slide out the pickup, adjust it, and pop it back in. The signal went into a computer where they were trying to match all the waveforms. We got it as close as it’s ever going to get. So, we’re pretty excited about it. I’ve got them in seven basses now. Our front-of-house guy loves them.

Do you have a practice regimen?

I have a great guitar collection. Every place you can sit down in my house has some sort of instrument right next to it. In fact, I just bought a ’72 Tele. So, I’ll always have these cool guitars or basses around my house. I’m kind of fidgety. I’m just one of those guys — I don’t drink, I don’t do drugs, I don’t go out very much. I just kind of hang out with my dogs and play a lot of bass and a lot of guitar. I’ve also got a studio at my house.

So, are you writing new tunes when you’re hanging out?

I just tinker around and let it happen. A lot of guys try to force it, like, “Okay, I have to do a record.” Then you just jump in too much for the wrong reasons. I think you have to let music kind of just happen. The music is always around you; you just have to be in the right head space to channel it through your head and your fingers — through your new fancy pickups and your cool amps [laughs]. Keith Richards once said, “I realized a long time ago that you don’t write songs; you receive them.”

It takes the pressure off, too, in a way. Music has always been a magical force in all of our lives. I wish people would turn off the news and turn off the internet and let the music take over. That’s all I did as a kid. I just love music and dogs; those have been the two constants in my life. My fear is that there’s a Kurt Cobain kid out there that’s not going to go into music because there’s no future in it, there’s no money for it, and it’s too hard, you know? Does AIC have any plans for a new album? When we get home, we’re definitely going to take a nice deep breath. I don’t think we’ll do anything this year; we’re just going to go home and chill out. But we’re always jamming and we’re always creating. Jerry will write a bunch of riffs, and then nothing will happen for a while. William has a solo album coming out, just one guitar and one voice. So, I think he’s going to jump into that in October. It’s good to do side stuff. I like to say that working with other people gets me out of my own hamster wheel.

Last time I was home for a bit, Mark Morton from Lamb Of God called and said, “Hey, will you play on a song?” I said, “Okay, where are you at? I’ll grab my favorite bass and meet you at the studio.” And he said, “I’m down in Orange County.” So, I said, “Well, I’m not going to drive to Orange County to play on one song, so I’m going to play on like, five [laughs]. Get me a hotel room and give me the address to the studio.” So, I went down there, and I got to track live with Steve Gorman from the Black Crowes — he’s such a great drummer — and Myles Kennedy [Alter Bridge] was singing on stuff, and I did tracks with Roy Mayorga [Stone Sour], who’s an amazing drummer, and [drummer] Ray Luzier from Korn, so I got to jam with these cool people.

What’s your takeaway from those experiences?

Every time I do that stuff, I’m really happy I did it. I always walk away feeling like that was a good thing for me. It’s all how you look at it, too. I’m blessed with a positive personality, I guess; I just really love music. It’s the best thing that ever happened to me. From an early age, I always knew I would be doing this for a living — not on this grand scale, but I always knew I would be a musician.

You never seem jaded by this business. You still have so much enthusiasm and humility.

I love that you [Freddy, the interviewer] go out and play Sabbath tunes. I’d be doing the same exact thing. It’s that feeling, though — I still have that well in my bones, in my DNA somewhere. When Ronnie James Dio’s Heaven and Hell came out, it was such a big event in my life. It’s like, “Oh my God, Dio’s in Sabbath!” And from a guy being in Ozzy’s band, I think Heaven and Hell might be my favorite record; I’m not sure. I love Masters of Reality, I love Sabotage. I love all the early stuff, but, boy, Heaven and Hell had such a modern twist. The tones, everything just came together. I thought that was just a fantastic record.

AIC did some shows with Geezer Butler’s new band, Deadland Ritual.

We did Rock am Ring [Mendig, Germany], Rock im Park [Nuremberg, Germany], these big Formula One racetracks. I thought they were a really good band. It’s probably the same thing with Geezer: He gets home and he gets bored and is like, “God, I just want to play bass.” We’re totally unqualified to do anything else at this point [laughs]. I don’t even know what I would do.

Do you ever work on bass technique when you’re at home playing?

It usually comes naturally, but sometimes I’ll force myself — like, “I’m going to learn [Rush’s] ‘La Via Strangiato’ if it’s the last thing I do and it takes me four days.” And I’ll really get into it. I’ll pop the track into Pro Tools, and I’ll even loop parts just to make sure I’m playing them with the same kind of feel and inflection. Or, say, “Highway Star” [Deep Purple]. I’m going to play it exactly the way Roger Glover did it. It’s a fun homework assignment to dive into other people’s bass playing, and then it creeps into your playing, too — the way you slide into a note or use a different finger to slide into the note, and then you’re in position for another thing to come out of it.

Do you ever utilize that information to refine songs you’re playing with AIC?

I’m really picking apart my playing lately — where my fingers are, where I’m picking and what position I’m in, to go into the next run or something. I’ll try it every single different way, too. It’s a process of elimination.

Tell me about your Warwick basses and why you like them.

Warwick puts LED fret markers on the top of the neck. So, on these dark stages, I’ll reach down and click that little switch, and the fret markers light up on the top. I have a blue bass with blue lights and a white bass with white lights, and it blows my mind. I giggle onstage every time I see it. It’s the stupidest thing, but I just love it. That youthful thing, that childlike wonder, is important. It comes naturally to me, but I stress that to kids: Don’t ever lose that. It’s so important to see the magic of all this stuff.

Have you ever thought about doing clinics?

I would actually love that. I’ve never done it and I don’t know how to do it, but maybe we’ll do something for Fishman and Warwick when I get some downtime, and if they want to do a signature line with the Fishman pickups. But I have to be careful about what I say yes to — I say yes, and then I’m on the road for four months again, and it’s just me and my tech in Japan or whatever. But I think I would be pretty good at it. It wouldn’t be like I would go and tell people what to do. I’ve seen clinics that are a bit too professorial, but hanging out, asking questions, showing people stuff — I think that would be fun.

Didn’t Zakk do them a lot, especially back in the days when you were in Ozzy’s band?

Yeah. We’d be on tour in Japan, and he’d ask me and [Ozzy drummer] Randy Castillo, “Hey, I’ve got a clinic — will you guys play Allman Brothers with me for 45 minutes?” This was in the early ’90s, so we’d stumble in there after being up all night drinking, and Zakk would just kill it. It was amazing to watch. He plays guitar more than any other person I know. We grew up together in the Ozzy band. I related to Zakk in that way — like, “Wow, I’m so on it, just like you are.”

The motivation is important. Like, why are you doing this?

For me it was because I wouldn’t want to do anything else. I’m constantly listening to new bands — different flavors, too. We’ve got this band Ho99o9 [pronounced “Horror”] opening for us, with the drummer from Dillinger Escape Plan [Chris Pennie], and they play to tapes and use keyboards, but it’s the most punk-rock show; it’s so high-energy. I’m the guy that when Monster Truck was opening for us, I’d jam with them every single night. I’d go out and play a song called “Sworded Beest” off The Brown EP. I picked the most obscure, heaviest song, and that’s the one I wanted to play. It would kind of piss off my drummer — like, “Why are you going out there and playing with those guys?” And I’d be like, “It’s a good warmup.” And he’d be like, “You’re giving it away too soon.” And I’m like, “Dude, I’m doing it. I’m sorry. I don’t know what to tell you, but I love it. I’m going to go play with these guys every night.” I just feel the universe is always pushing me forward somehow. l