Jump Head

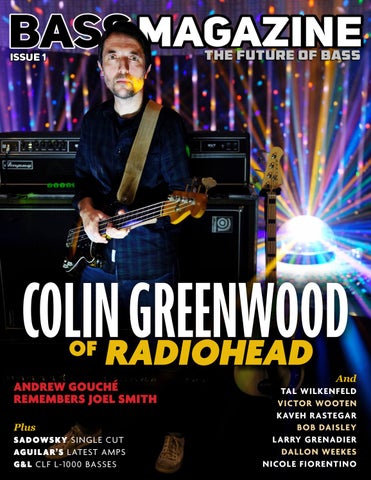

COLINRADIOHEAD GREENWOOD OF

And

ANDREW GOUCHÉ REMEMBERS JOEL SMITH Plus SADOWSKY SINGLE CUT AGUIL AR’S L ATEST AMPS G&L CLF L-1000 BASSES

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ;

TAL WILKENFELD VICTOR WOOTEN KAVEH RASTEGAR BOB DAISLEY L ARRY GRENADIER DALLON WEEKES BNICOLE A S S M A G A ZFIORENTINO INE 1

ARTIST:

Jump Head

MADE TO PERFORM INSPE CTOR :

MODE L:

COLO R:

PICKU PS:

TUNE RS:

NECK :

SERIE S:

FRETS :

INTRODUCING THE AMERICAN PERFORMER SERIES FEATURING ALL-NEW YOSEMITE ™ PICKUPS, HANDCRAFTED IN CORONA, CALIFORNIA

2

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

©2019 Fender Musicial Instruments Corporation. FENDER, FENDER in script, PRECISION BASS, and the distinctive headstock commonly found on Fender Guitars and Basses are registered trademarks of FMIC. Yosemite is a trademark of FMIC. All rights reserved.

Contents Gear Reviews:

Features 20. Nicole Fiorentino The ex-Smashing Pumpkins bassist returns with her new band, Bizou. By Jon D’Auria

28. Victor Wooten The bass great gives his take on Miles Davis classics with his playing on a new live album. By Chris Jisi

32. Pancho Tomaselli After holding it down for War and Tower Of Power, the Ecuadorian bass ace unleashes new albums with Philm and Ultraphonix. By Jon D’Auria

36. Adeline

60. Andrew Gouché Remembers Joel Smith

108. Aguilar’s Tone Hammer 700 & SL 115

Gospel great Andrew Gouché reminisces on a lifetime of friendship and grooves while paying homage to the great Joel Smith. By E.E. Bradman

112. Sadowsky’s Single Cut

66. Colin Greenwood In his first interview in years, Radiohead’s enigmatic and highly influential bass phenom opens up about his perspective on bass and dishes on his most iconic bass lines. By Jon D’Auria

80. Tal Wilkenfeld

115. G&L CLF L-1000 Basses

Columns 118. Jazz Concepts Bach for Bassists. By John Goldsby

121. The Inquirer To the Future of Bass! By Jonathan Herrera

122. Alternatives

The Paris-by-New York low end songstress unleashes a soulful and funky new solo album. By Bill Leigh

With a new solo album and a new musical identity, Tal Wilkenfeld shows the world that she’s more than just killer chops and virtuosic licks. By Chris Jisi

40. Kiyoshi

92. Bob Daisley

Slap superhero Kiyoshi delivers her third solo album and talks about her energetic live persona. By Jon D’Auria

The man behind the thunderous foundation of Ozzy Osbourne, Gary Moore, and Rainbow recalls his lifetime of studio and stage work. By Freddy Villano

Freeting-Hand Finger Permutations. By Patrick Pfeiffer

46. Larry Grenaider

Don’t Knock the Tribute Life. By Karl Coryat

124. Beginner Bass Base

128. Berklee Bass Babylon Go Produce Yourself! By Steve Bailey

The upright master discusses his studio techniques, his love of alternate tunings, and the lonely task of recording solo. By John Goldsby

96. Kaveh Rastegar

130. Partners

On his debut solo album, the John Legend and Kneebody bassist reveals a musical voice all of his own. By Chris Jisi

Leo Fender & the “Group of Guys” By Jim Roberts

54. Dallon Weekes

102. Complete Transcription

Fresh off of leaving his role in Panic At The Disco, Dallon Weekes returns with his drum and bass duo, IDK How. By Jon D’Auria

Kaveh Rastegar’s “Roll Call.” By Chris Jisi

Departments 4. From the Editor 6. 10 Questions With Bubby Lewis 8. Spins, Streams & Downloads 12. Bass Magazine’s 2019 NAMM Wrap Up

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

3

From the Editor Let’s Take it from the Top. Bass Family,

Jisi, Bradman, D’Auria, and Friedland in Los Angeles, 2011

4

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

Well, here we are, the debut issue of Bass Magazine. How did we get here? It’s a long story with lots of plot twists, but we’ll grab a beer sometime and I’ll fill you in then. In short, when the world’s #1 magazine for bass players was sold to a European publisher last year, it turned into a completely different beast — and the folks behind its 30 years of success wondered how to keep the spirit of “digging deeper” alive. Here is the result, and we couldn’t be more excited to bring you this issue, and more so, this magazine. Not one bit of this would’ve been possible without the amazing group of writers and editors that we have on our roster. Seeing the names Chris Jisi, Elton Bradman, Jim

Roberts, Ed Friedland, Karl Coryat, Jonathan Herrera, Paul Haggard, John Goldsby, Rod Taylor, Freddy Villano, Patrick Pfeiffer, Bill Leigh, or our GM Tim Hill on our masthead, I can’t believe that we’re all back at it together again so quickly. In the beginning when our core group of Chris, Elton, Tim, and myself first embarked on this, we knew we had some mountains to climb, and gathering our team was step one. Of course there are so many other people involved. The entire bass community rallied around us upon our launch, and all of the artists, publicists, gear companies, luthiers, and bass experts have been instrumental in making this happen. There is no big corporation or publishing company behind this one bit; everything comes directly from us. Every single ad you see in these digital pages was placed with a blind leap of faith. We went to gear companies with only a tablet filled with bullet points, a few numbers scribbled on notepads, and the ambition that we would make this thing work. Contracts were sealed with handshakes, hugs, and the promise that we wouldn’t let each other down. And we won’t. If that doesn’t sum up the amazing bass world around us, then I’m not sure what does. It’s all about love, respect, and supporting one another, and always has been. And finally, the content. We’re beside ourselves looking at the editorial calendars and

layouts for our first series of issues. We have some amazing things in store that we can’t wait to reveal to you in the coming months, but as for this issue, we’re beyond stoked. I’ve been a massive Radiohead fan for decades and as soon as I became a bass journalist I set some goals, and atop those goals was interviewing Colin Greenwood. I had never known of him doing interviews and always wanted to know which bassists influenced his playing, how he writes his lines, and how such a patient player can create such seismic moments when he wants to. Now those questions are finally answered (big thanks to RS!). Additionally, we have phenomenal features on Tal Wilkenfeld and her new album; we get the latest from Victor Wooten, tons of interviews with our favorite artists, and lots of in-depth reviews. And we’re thrilled to bring you columns from the bass experts who have been writing them for three decades. This issue, and each that will follow, is bursting at the seams with content. So dig in and enjoy. Don’t hesitate to hit me up and let me know your thoughts on our new zine at: jon@bassmagazine.com, and follow us on our socials and our website to stay in the loop. Cheers to the next chapter, and cheers to the future of bass!

Jon D’Auria Editor-In-Chief

Volume 1, Issue 1 |

bassmagazine.com

Editor-In-Chief JON D’AURIA Senior Editor CHRIS JISI Editor-At-Large ELTON BRADMAN General Manager TIM HILL Copy Editor KARL CORYAT Art Director PAUL HAGGARD CONTRIBUTORS Ed Friedland Jim Roberts Jonathan Herrera Freddy Villano John Goldsby Rod Taylor Patrick Pfeiffer Bill Leigh Stevie Glasgow Vicky Warwick Patrick Wong FOR AD INQUIRES CONTACT:

tim@bassmagazine.com ALL OTHER INQUIRIES CONTACT:

jon@bassmagazine.com chris@bassmagazine.com elton@bassmagazine.com All Images, Articles, and Content ©2019 Bass Magazine, LLC

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

5

10 Questions with

R 1

What was your first bass? The first bass that I played was a Cort Curbow 5-string.

6

Bubby Lewis

obert “Bubby” Lewis is certifiable bass ninja. His groove is like no other, his chops are the thing of legend, and if you haven’t seen his acrobatic/yogi finger chordal stretches on his MTD 6-string basses, then you need to check out his Instagram page immediately (https://www.

instagram.com/bubbylewis). He’s been holding down bass duties for heavyweight artists such as Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, Lupe Fiasco, Tha Game, and Stevie Wonder for years and is frequently a mainstay in Japan for various artists in those parts. He took a quick break from his practice regime to answer our 10 Questions.

2

4

What’s something we’d be surprised that you listen to? Lately I’ve been checking out a ton of the new banda and mariachi stuff. I’ve always loved how every culture has something traditional and special to offer musically.

3

What’s one element of your playing you’ve been working on recently? I’m working on becoming more familiar with my instrument; knowing where everything is at all times and being able to execute the things I hear in my head.

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

What was the first concert you ever attended? The first big concert I attended was John P. Kee, held at my church when I was a little kid.

5

What’s the best concert you’ve ever been to? Man, that’s tricky. Allan Holdsworth, Frank Gambale, CHON, John Legend, Big Bang, and Commissioned … I could go on all day.

6

If you could have lunch with any bass player, alive or dead, who would it be? I would want to sit down and eat with John Patitucci, Geddy Lee, Paul McCartney, Tom Kennedy, and Anthony Jackson.

7

If you could sub for a bass player in any band, who would it be? I’d sub for all the folks playing bass on the anime and video games in Japan.

8

What’s the best advice you’ve ever been given about playing bass? To have my own voice and be the artist I want to be.

9

What the most embarrassing thing that’s happened to you during a gig? Man, I took a dump on myself onstage [laughs]. It was in Australia back in 2010 with Snoop Dogg. We were playing “Gin and Juice,” and as soon as I hit a low note in the chorus … it happened. I had to ignore it and finish the show. Dude, it was only like the third song in.

10

If you weren’t a bass player, what would you be doing? I’d be in the comic book, anime, voiceover, or videogame industry. Or a person who goes around doing food challenges like on Man vs. Food.

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

7

Spins, Streams & Downloads

like any reasonable 12-yearold, we’re still laughing about it. But like everything he does, that’s just Mono being Mono, and this album once again proves that he refuses to be anything else. —Jon D’Auria

MonoNeon My Feelings Be Peeling The infinitely funky and highly prolific MonoNeon is back with yet another album that falls into suit with his previous work as a groove clinic of raw musicality and candid lyricism. Laying down funky line after funky line, the nine-song LP features Mono on bass and guitar with a little help from collaborators in the form of fellow low-ender Alissia Benveniste and drummers JD Beck and Sam Porter supplying intricate beats. The album kicks off with the laid-back grooves and crisp guitar strumming of “Don’t Make This World War 3,” and then continually builds with increasingly fast and soulful hits like “She Was Round & Brown” and “She Look Cute With My Hoodie On.” Every song features the intense musical mastery that Mono has become viral for, but the continual growth and expansion of his vocal range and one-ofa-kind songwriting won’t be lost on any listener who cops his latest work. If you’re just in it for a good time, don’t skip out on the first single, “Fart When You Pee” — because

8

Tedeschi Trucks Band Signs Whose Hat Is This? Everything’s OK Tim Lefebvre’s five-year stint in TTB (now anchored by Atlanta bassist Brandon Boone) resulted in two sterling studio sides and one live album, exposure to a swath of southern music for Lefebvre, and a cadre of new grooves for our ears, as he processed said music through his jazz-rooted filter. It also has produced an exciting experimental quartet,

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

Whose Hat Is This?, made up of Tim and his TTB mates Kebbi Williams on tenor sax and flute, and drummers JJ Johnson and Taylor “Falcon” Greenwell. On their dizzying debut, Everything’s OK, cut live in Baltimore with guest hip hop artist Kokayi, the unit’s all-improvised set leads to many noteworthy moments. This includes “Jon Homes,” which rides Lefebvre’s kinetic P-Bass boogaloo, “X’s for Eyes,” Tim’s random interval exploration, via pick and effects pedals, “If I Had to Decide Between the Pork and You,” a free-tempo, bluesy theme and development on acoustic bass, and the electric-Miles-esque “Well Alright, Playboy.” As for the song-rich Signs, it’s a worthy swansong for Lefebvre, who shares three co-writes and reminds how interwoven he was in the band’s creative fabric with lyrical lines that never overstep but always serve and swing. It’s also a sad goodbye to the brilliant, late keyboardist/ flautist Kofi Burbridge, who was pivotal to TTB’s musical DNA, and who shared a special bond with Lefebvre at live shows, where the two enjoyed a stepout segment. Track-wise, Tim adds a minor 9 subhook to the simmering ballad “I’m Gonna Be There,” drives the riff-heavy “Shame” and the trippy “Still Your Mind,” and serves as the funky, bouncing rhythmic core on “Walk Through This Life.” Five years well spent. —Chris Jisi

Jump Head

Potty Mouth

Red Dragon Cartel

Flight Of The Conchords

Snafu Six years after their debut album, Hell Bent, the poppunk trio Potty Mouth has returned with their sophomore effort. Even beyond their obvious maturation as band, the new album brings to mind the work of popular ’90s acts such as Blink-182, Garbage, Weezer, and even Nirvana, but the bottom line is that the bandmembers are damn fine songwriters. Ally Einbinder kicks out charging bass lines that steadily pulse under the vocally melodic work that is just about as catchy as hooks can be. Einbinder serves as so much more than just the foundation, though, as her register-wandering lines serve as ear candy on tracks like “Massachusetts,” “Plastic Paradise,” and “Bottom Feeder.” If Snafu is the kind of evolving they’re already proving with just two albums, it’s safe to say that we can’t wait for their third effort. —Jon D’Auria

Patina Former Lynch Mob/Ace Frehley bassist Anthony Esposito returns to the limelight on Patina, the latest from a realigned Red Dragon Cartel, the band launched in 2014 by exOzzy/Badlands guitarist Jake E. Lee. Not only did Esposito play bass on Patina, he also cowrote, co-produced and engineered the record, so it is a testament to his well-rounded skill set. Musically, Patina harkens back to the blues-based hard-rock swagger of Badlands, albeit with a more modern attack. Check out “Havana,” “Bitter” and “Chasing Ghosts” for prime examples of Esposito’s deep-pocket grooves and how well they complement Lee’s wickedly unique riff flexing. —Freddy Villano

Live in London The self-proclaimed “New Zealand’s fourth most popular guitar-based digi-bongo a capella-rap-funk-comedy folk duo” Flight Of The Conchords, who became wildly popular from their eponymous comedic HBO series, have just released a live album and DVD that features the hilarious two-piece playing a new batch of side-splitting songs. But don’t be fooled with the non-stop laughs — these guys can play. And more important to those reading this, Jermaine Clement is seriously good at bass, or as their fictitious manager calls it, “the dad guitar.” Simply being really talented at the 4-string is impressive enough, but try doing that while singing in a multitude of voices, delivering hilarious punch lines, and interjecting constant banter with bandmate Brett McKenzie, all while keeping a straight face in front of a thunderous audience. The gig is no joke, and nobody does it quite like Jermaine. And he delivers impressive tone as he switches from Hofner 500/1 to a Fender Tele-

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

9

Spins, Streams, & Downloads

10

caster Bass throughout their live sets. Even Brett picks up the bass for one song, and not surprisingly, he holds it down, too. Not bad for the fourth best band from New Zealand. —Jon D’Auria

tear), explore the elongated 9/4 groove of “Plan Nine” with a greasy agenda, and in the disc’s take-notice moment, relentlessy drive the Weather Report-intoned “Arboreal.” —Chris Jisi

Fima Ephron

The Beta Machine

Songs From the Tree Fima Ephron is an undersung Big Apple bass treasure, deep in groove and taste, and a talented composer. His latest— recorded in ten hours with the killer esemble of saxophonist Chris Potter, guitarist Adam Rogers, drummer Nate Smith, and keyboardist Kevin Hays—is a first-rate effort rooted in the Gotham electric jazz vein of artists like Michael and Randy Brecker, and Steps Ahead. Helping to nudge the genre forward is Ephron’s post-session sonic touches, adding keyboards, percussion, voices, and deft edits and mixes (as well as David Torn’s live looping on “Signs”). The other key is Ephron’s holy hookup with drum force Smith. The pair navigate three different feels on “Fortune” (with Smith unleashed behind Potter’s solo

Intruder When he hasn’t been on the road touring the world over the past seven years with A Perfect Circle, Puscifer, Eagles Of Death Metal, or Thirty Seconds To Mars, Matt McJunkins’ attention has been focused solely on his own project, The Beta Machine. As a collaboration with his rhythm section partner in APC and Puscifer, drummer Jeff Friedl, The Beta Machine released their debut EP, All This Time, in 2017 and have now unleashed their highly anticipated album, Intruder. Unlike his sideman role in his other bands, McJunkins takes the spotlight as Beta’s frontman, and his vocals and driving playing lead the way on their dynamic alternative-rock sound. The first single, “Embers,” plunges forward on McJunkins’ steady lines

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

and colorful vocals that have hints of David Bowie accents. Tracks like “Precious Design” and “The Fall” exhibit his ability to capture seriously dirty tones, although the heaviest bass cut of the album comes from “Bleed for You,” where his anthemic vocals belt over the speedy bass work of his right hand. For fans of his other bands, Intruder is a must listen — not only because it slays from front to back, but also because it gives a deep insight into McJunkins’ skillful style as a songwriter. —Jon D’Auria

Beastie Boys Book

The all-encompassing, everything-you-ever-wantedto-know about the Beastie Boys memoir is a supremely entertaining read that takes you from the innovative MCs’ early days growing up in the five boroughs all the way through the peaks of their illustrious career as titans of hip-hop. While the book meanders through the evolution of three young punk rockers who reveled in debauchery and eventually grew into enlightened and iconic artists,

the true focus of the tale shines light on the genius of Adam Yauch (MCA). Since Yauch passed away before the book was written, his life is told through the eyes of his best friends and bandmates, Adam Horovitz (Ad Rock) and Michael Diamond (Mike D). We quickly find that Yauch was the center and the heartand-soul of their trio. More than just a supreme emcee and bass player, Yauch was the man with all of the answers, a Zen-like figure who loved getting his hands dirty. His bandmates explain how he tinkered with an analog

tape machine and figured out how to reverse the reel, which led to the iconic beat behind their early single “Paul Revere.” They also chat up his subtle genius in songwriting, and how one time between takes in the studio, he was fiddling around with some chords and a funky run that became the entirety of their smash song “Sabotage.” The book goes deep into Yauch’s lifelong passion for bass, and how he gained so much from studying his idols Ron Carter, Darryl Jenifer, Carol Kaye, Jah Wobble, and Aston Barrett. Even after their wild com-

mercial success, Yauch was known to keep a very simple existence (partially due to his Buddhist spiritual awakening), and despite all of the money they made, he lived in a tiny New York apartment with nothing of value in it except for his basses and amps. In fact, it seems as though he was always happiest in life when he was playing his 4-string. This book doesn’t simply serve as a candid trip down memory lane for superfans and causal listeners alike, it reminds us of how damn much we miss MCA. —Jon D’Auria l

GHS short scale bass strings are more than just smaller versions of traditional strings. After extensive player input and research, the result is a 32.75” winding length that fits more short scale basses than any other string brand. Read our story at www.ghsstrings.com/strings/bass

WE WENT TO GREAT LENGTHS TO CREATE THE RIGHT STRING.

STRINGS

PLAY WITH THE BEST ™ g h sst ri n g s .com

SUPER STEELS PROGRESSIVES BASSICS BASS BOOMERS

Evan Marien Photo by Eric Silvergold

ROUND CORE BASS BOOMERS PRESSUREWOUNDS BALANCED NICKELS BRITE FLATS PRECISION FLATS

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

11

Gear

WHAT’S NEXT? Bass Magazine’s Winter NAMM 2019 Wrap-Up By Jon D’Auria

B

Magazine hit the Anaheim Convention Center in full force to check out all of the latest bass offerings that you come to expect from the biggest U.S. instrument trade show of the year. More than usual, we were blown away by all of the new innoass

12

vations and models that bass builders, amp companies, luthiers, string makers, and effect creators dished out this year. Here’s a selection of some of the best bass gear that caught our attention at Winter NAMM 2019.

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

Fender

Duff McKagan Signature Series

For his latest signature model, Duff McKagan threw it back to the same design of his ’80s Jazz Bass Special that he used to record Guns N’ Roses seminal album Appetite for Destruction, and Fender delivered. With a sexy design featuring pearloid block inlays, a black headstock, a drop-tuner, and two sleek finish options, this new series was the talk of NAMM. fender.com

Bergantino forté HP

Now bringing 1,200 watts of tone and power to its forté collection, Bergantino has unleashed the latest addition to its workhorse amp line with the forté HP. Like all Bergantino amps, the forté HP offers highly customizable options, all in a compact package. bergantino.com

Nordstrand

Acinonyx Basses

Not surprisingly, Carey Nordstand delivered perhaps the most fun bass we played at the show with his brand new Acinonyx short-scale prototype. Modern tributes to Goya Panther basses, Acinonyx basses feature tone buttons that greatly alter the frequencies you can cop on these addicting compact 4-strings. nordstrandaudio.com

(Bonus) Nordstrand NordyMute

This new foam mute with a wood covering stopped us in our tracks. Simply pop this lightweight device onto your strings near your bridge, and all of a sudden you get killer Bobby Vega-esque muted-picking sounds with automatic staccato resonance and tone similar to that of an upright bass. We couldn’t get our wallets out fast enough. nordstrandaudio.com

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

13

WINTER NAMM 2019

Aguilar Amplification SL 115 Cabinet

Weighing in at only 34 pounds, this lean, mean 15" cabinet rumbles deep, but with all the precise clarity that Aguilar has become well known for. We heard it isolated and were blown away, but now we’re daydreaming about what this heavy-hitter sounds like paired with an AG 700 head and SL 410 cabinet. aguilaramp.com

MTD

H34D5 Headless Bass

We had to do a double take when we first saw MTD’s new H34D5 headless basses, but then we did a triple take when we heard the tone these beauties produce. Constructed with a highly figured maple top on a mahogany body with a maple neck and bird’s-eye maple fingerboard, these innovative new axes are a perfect addition to MTD’s collection. mtdbass.com

Stonefield

Mighty Mini Cabs

Ampeg

Liquifier Analog Chorus

Utilizing dual chorus circuits, Ampeg’s Liquifier Analog Chorus creates a thick, juicy, modulated tone. With the easy-touse rate, depth, and effect level knobs, you can dial them in subtly for tone enhancement or crank it up for heavy waves of chorus frequencies. Its sparkly purple metal casing pretty much seals the deal on its own. ampeg.com

14

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

Always one for crafting innovative new bass creations, Stonefield’s Tomm Stanley has entered the amplification game with his new line of Mighty Mini cabinets. Available in 8" and 6.5" speaker configurations, these compact cabs pack some big tone, and they’re definitely the coolest-looking colorful new amps to hit the market. stonefieldmusic.com

WINTER NAMM 2019

Dunlop

MXR Dyna Comp Bass Compressor

With Sire bass in hand, Darryl Anders was happy to demo MXR’s new Dyna Comp Bass Compressor for us, and along with his highly enjoyable funky playing, we were super impressed with this small stompbox’s ability to home in on some serious tone. What sets this compressor apart is how it leaves your low end intact while letting you alter your dynamic range to your heart’s desire. jimdunlop.com

Gallien-Krueger Legacy Amps

GK once again wowed bass goers at NAMM, this time with its new Legacy series of amps. In honor of its 50th anniversary, GK released these powerful new heads with 500, 800, and 1,200-watt models. Not only do they look amazingly sleek, they deliver all of that iconic GK tone. Additionally, GK unveiled its Fusion S, Fusion +, and Plex-series amps to cover all sonic territory. gallien-krueger.com

Markbass

Kilimanjaro & Kimandu Basses

When Richard Bona puts his name on a product, you know it has to be good. That’s why we weren’t surprised that the first line of bass guitars from Markbass is stellar on all fronts. With a highend model (the Kilimanjaro) and a less expensive series (the Kimandu), these 4 and 5-strings basses are beautifully crafted and boast phenomenal tone that we got to hear played by Bona himself. markbass.it

BackBeat

Rumble Pack

One item generating a ton of buzz this year (both figuratively and literally) is the innovative new wearable rumble pack from BackBeat. This small device clips to the back of your bass strap and vibrates along with every note and bass line you play. Great for players who use in-ear monitors or play through smaller rigs, we feel like this innovation is a must-have. getbackbeat.com

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

15

WINTER NAMM 2019

Genzler Amplification BA410-3 SLT

We made our way over to the Genzler booth with our very own Ed Friedland, who demoed Genzler’s new BA410-3 SLT slanted cabinets for us. The four 10" neodymium woofers pack so much power and clarity into every note, and we were able to hear the advantages of the slanted cabinet design, as they projected a thick, rich tone that blew our socks off. We credit Ed for that effect as well. genzleramplification.com

Sadowsky

Spruce Core Single Cut Bass

We felt lucky just being able to see Sadowsky’s new Single Cut bass in person, but it was an amazing experience to hear the man behind the bass himself, Roger Sadowsky, explain that he chose spruce wood because of its immense resonance — that’s why its used for pianos, mandolins, and violins. Listening to its Sadowsky mid-boost preamp and soapbar pickups in action solidified Roger’s point. sadowsky.com

G&L Guitars CLF L-2000

We spent a lot of time lingering around the G&L Guitars booth the entire week because we just couldn’t get enough of the company’s 2019 bass offerings. One of our favorites is the CLF Research L-2000 bass, with two Magnetic Field Design pickups that can make the tone shift from a classic P-Bass sound to a powerful gain-driven StingRay. We couldn’t put it down. glguitars.com

16

Warwick

Shavo Signature Series Basses

Shavo Odadjian of System Of A Down is Warwick’s latest player transplant, and to welcome him over to their family, they gave him not one, but two stunningly designed signature basses. Created in both Streamer and Idolmaker body styles, the new signature basses were designed and conceptualized by Shavo himself on a recent trip to Germany, and we can’t wait to try one out ourselves. warwickbass.com

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

WINTER NAMM 2019

Elrick Bass Guitars

Handcarved Icon Gold Series Bass

With beautiful hand-carved bodies, bolt-on necks, and a heel-less design, the new Icon Gold series is yet another masterpiece of building from luthier Rob Elrick. Available in 4- and 5-string models, these basses have 34" scales, come equipped with Bartolini pickups, and have swamp-ash bodies and quarter-sawn hard-maple necks that make their level of playability exceed all expectations. elrick.com

Mayones Guitars & Basses

Phil Jones Bass

Micro 7 and BP 800

Phil Jones Bass always brings a slew of innovative new offerings to every NAMM show, so we decided to profile two new products. The compact Micro 7 combo amp is super lightweight at only 15.5 pounds, and it kicks out a sound much bigger than its 7" driver and 3" tweeter should be able to convey. PJB also unveiled its new BP 800 head, which weighs only 5.7 pounds and sits at a tiny 7.5" wide. For the gigging bass player on the go. pjbworld.com

Hadrien Feraud 5-string Signature Jabba Bass

Mayones debuted the latest addition to its Signature Hadrien Feraud Jabba Basses with a new 5-string model. We’ve been huge fans of his original 4-string signature, so this bass was something we had to check out. With a profiled swamp-ash body, spruce top, and block inlay-lined frets, this is one of the sexiest-looking basses we stumbled onto. mayones.com

Lakland

Geezer Butler Signature Bass

The new all-black 55-94 Geezer Butler Signature model has a classic look and feel suited for the man behind Black Sabbath. Made of deluxe buckeye burl with an ebony fingerboard, this bass was just one of the many impressive new models that Lakland brought to the show. We almost got into a wrestling match with Ben Kenney to see who was going to take it home with them. (Full disclosure: He won.) lakland.com

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

17

WINTER NAMM 2019

Blast Cult

Fretless Thirty 2 Bass

We swung by Blast Cult’s booth to witness a masterclass on grooving on upright bass from Miles Mosley, and ended up falling in love with the company’s latest fretless Thirty 2 Bass model. With a slick green paint job and a modern-meets-vintage design, this new 4-string was infinitely fun to play and boasts supreme sound. blastcult.com

LEH Guitars

Offset 4-string Bass

If our wrap-up had a “Rookie of the Year” award, it would definitely go to Lisa Ellis Hahn for her flagship bass series, the LEH Offset 4-string. But don’t be confused — Lisa is no rookie at all, as she has served as the top builder at Sadowsky Guitars since 2005 and is a seasoned veteran at making basses. The Offset reflects all of her luthier prowess, and we’re thrilled to see what’s next from her collection. lehguitars.com

Music Man

Joe Dart Signature

While it’s yet to be determined whether this will be a one-off prototype or something Music Man will put into production in the future, we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention Joe Dart of Vulfpeck’s new signature bass. With a full-scale 34" neck, natural finish, and simple one-knob setup, this bass is one of a kind. Big thanks to Joe for letting us steal it for a bit. music-man.com

Tech 21

SansAmp YYZ Geddy Lee

Taking the design of the previously released rack-mounted GED-2112 made for Geddy Lee, SansAmp has run with that engine and made it even smaller with the new YYZ pedal. This analog pedal allows you to cop Geddy’s tone and a versatile range of other sounds with a drive control, 3-band EQ, and a deep drive knob that will thrust your playing into the limelight. tech21.com

18

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

WINTER NAMM 2019

Ashdown

CL-310DH Cabinets

Originally constructed specifically for Guy Pratt, these cabinets recently went into production and have a unique configuration of three 10" custom Ashdown drivers, and two high-frequency horns to project at loud volumes. Rated at 450 watts at 8 ohms, these tall and slender cabs have a unique look and sound. ashdownmusic.com

Hartke

HD508 Bass Combo

We visited the Hartke booth to listen to Victor Wooten perform with John Ferrara, and also to check out Hartke’s new HD508 combo amp — and we weren’t disappointed on either accounts. Weighing in at only 49 pounds, this combo features a 500-watt Class D amplifier and four 8" HyDrive speakers. It sounds killer. samsontech.com/hartke

La Bella

Olinto 5-string

La Bella’s Olinto line of basses has expanded with a 5-string model, and it’s every bit as phenomenal and vintage-sounding as all of La Bella’s 4-strings. Highly customizable options for these basses include a choice of body wood: alder, swamp ash, northern ash, mahogany, makore, black limba, and roasted. labella.com

GRBass Amps

ONE Pure Sound Amp

Italian-based GR Bass has released its latest amplifier that packs a lot of power into a small frame. The new ONE amp (available in 1,400-, 800-, and 350-watt models) have deep and bright filters, a preamp exclusion function when “Pure Mode” is initiated, an integrated tuner, a high-quality headphone amplifier, and amazing tone all around. grbass.com l

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

19

Bizou

NICOLE FIORENTINO

Return To The Spotlight By Jon D’Auria | Photos by ZB Images

IN

2010, Nicole Fiorentino’s life changed forever when it was announced that she was the new bassist for alternative rock legends Smashing Pumpkins. She was no stranger to the limelight, having previously been a member of other popular rock acts such as Veruca Salt, Spinnerette, and Light FM. Similarly, that same year she also formed the band The Cold And Lovely, which made for a nonstop touring schedule and also put Fiorentino’s writing and recording skills to the test. She went on to release Teargarden by Kaleidyscope (2010) and Oceania (2012) with Smashing Pumpkins, and The Cold And Lovely’s self-titled debut (2012) and Ellis Bell (2013). She was up for the test, and delivered massive bass performances on each of the al-

20

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

bums, while solidifying her prolific stature as a bass player. Fiorentino’s magnetic stage presence and staggering tone made her stand out and become a favorite among fans of both bands. When we had a chance to discuss her playing with Billy Corgan, the Smashing Pumpkins frontman likened her style to that of Chris Squire of Yes, an incisive comparison given Fiorentino’s strong rhythmic propulsion and her cutting midrange sound. She continued to develop a mature musical identity with both of her musical outlets, but in 2014 she announced that she was departing from the Pumpkins lineup, and in 2016 it was revealed that The Cold And Lovely would be taking an indefinite hiatus. The non-stop touring and studio schedule that she had grown accustomed to had

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

21

Nicole Fiorentino

now subsided, and for the first time in a long time, she allotted herself some space away from music. In 2016 she formed her own business, a pet-sitting and charitable organization in Los Angeles that fueled her other love besides low end, dogs and cats. Content with her new lifestyle, it was going to take something special to make Nicole want to don her bass once again, and that project found her late in 2018 when her close friends approached her to start a new band. The initial jam sessions reinvigorated her love of playing, and before long, the group Bizou was minted and ready for action. In her own words, Nicole describes Bizou’s music as a sweet and poppy brand of dark beach goth that resembles if Siouxsie Sioux had a baby with Lush. We’d explain it better than that, but we really can’t. And naturally, the root of the music lies in the powerful, chorus and gain-driven lines of Fiorentino, who seemingly hasn’t skipped a beat in her time away. Bizou has now recently released its self-titled debut EP, with a distinctive vibe that makes this nascent outfit already sound like a seasoned band. But that’s exactly what we’ve come to expect from any project Fiorentino steps into.

L I ST E N Bizou [2019] GEAR BASS Bonneville ’60s-inspired J-style bass RIG Aguilar Tone Hammer 500 head, Aguilar SL 212 cabinet EFFECTS Electro-Harmonix Neo Clone Analog Chorus, Boss CEB Bass Chorus, Tech 21 SansAmp Bass DI STRINGS DR Strings 45 Pure Blues Round Wounds

A

fter you departed from Smashing Pumpkins, you decided to take a break from music. What made you want to return? I started my business and wanted to focus on that, and with any new company, the first two years are the hardest, so I really didn’t have time for anything else. But after a while I was itching to play again. I was waiting for the right thing to come along, something that just made sense to me. I’ve known Josiah [Mazzaschi] for years; we were in Light FM together right before I joined SP. Nicki [Nevlin] is my best friend, and we’ve been in many projects with each other over the years. Erin [Tidwell] is a longtime friend and played drums in my band The Cold And Lovely, and we met Mina [Prietto], our badass singer, through Erin. Going into this we all had a great rapport and a good under-

22

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

standing of how we all work musically. We started writing songs and it all came together very naturally. How did you approach the bass in this band differently than your work in Smashing Pumpkins and The Cold And Lovely? I’m not sure if it’s because I took a long break or what, but there is a different vibe altogether in this band. I feel like it’s a clean slate for me as a bass player. I feel like the people I’m working with are really open to my ideas, not that Billy [Corgan] or Meg [Toohey] weren’t open — I think I was just in a very different place in my life when I was in both of those bands. Billy always encouraged me to play from my heart, but it was a very high-pressure situation. Meg was encouraging, too, but there’s a whole other layer added being in a band with your significant other. I feel very free in this band and very supported. Also for the first time in a long time I’m really just doing this for fun, because I love to play. And that’s a good place to be as a musician. What was your process writing your bass parts? Josiah is our secret weapon; he’s a jackof-all-trades kind of person. He writes the core of the songs, and we all work on our own parts based off that. I like to sit with the songs at home and work out my parts, and then when we rehearse I’ll often rearrange my parts depending on what Erin and Nicki have come up with. It’s a fun collaboration, and we are all super open to each other’s ideas. Your bass lines have almost an ’80s postpunk, gothic feel to them à la the Cure or Joy Division. The Cure are my all time fave, and Joy Division as well. I’ve always loved Peter Hook’s midrange melodic style, and it plays into how I approach the bass when writing my parts. The rest of the band listens to a lot of Siouxsie Sioux, New Order, Chameleons, Curve, Wire, and all those similar bands. There are a lot of elements, like synth lines and added melodies. How did you find your harmonic space?

Jump Head

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

23

Nicole Fiorentino

24

dancing. They just can’t help but move their little booties to it. It’s our disco jam. How did you achieve your tone for this EP? In the studio we recorded with both a DI and amp signal and blended the two. A lot of the effects were applied with Pro Tools in the mix. The DI was a SansAmp, which gave it a little more drive. We used the SoundToys Decapitator 5 plug-in quite a bit, and the Electro-Harmonix Neo Clone Chorus and some Waves plug-ins. We also used a Boss Super Chorus pedal. I love choruses. For the song “Scars,” we ended up using a live recording on the EP rather than the studio tracks, because, why not? And you used basses different from the Fenders and Reverends that you had previously. My friend Lyndz McKay [bonnevilleguitars.com] builds these gorgeous vintage-inspired guitars and basses that just play beautifully. They feel so good in your hands,

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

Bizou performing live.

PRISCILLA C. SCOTT

We compromise. Sometimes there will be a keyboard part that’s really cool, but then I write a part that makes more sense for the song, so we’ll just take out the keyboard, or I’ll write a part but it’s clashing with the keys so I’ll simplify it or take it out altogether. I usually start with more and then have to pare it back a little. I tend to be too wordy with my bass parts, and I always have to check myself. Your lines in “Love Addicts” really drive the whole song. I think it’s inspired by The Cure’s Disintegration [1989]. That album is often in my mind when writing bass lines. It’s such a classic. Specifically “Fascination Street,” it’s just so groovy and driving. “Like Rain” is a grooving song where you really dig in. That’s probably my favorite song to play live right now. Some of our stuff is pretty moody, but that one always gets the crowd

CLF Research L-2000

made in Fullerton, California

Nicole Fiorentino

PRISCILLA C. SCOTT

too. I know a lot of people are making relic guitars now, but Lyndz’s guitars are something special. He gave it to me about four years ago when was in The Cold And Lovely, and it has been my main bass ever since. They’re inspired and designed after ’60s [Fender] Jazz Basses. How did playing in Smashing Pumpkins impact you as a bass player? Oh my God, in so many ways. Stylistically, I always felt I had the freedom to be me, but I had to figure out and step into myself in order to hold my own. I had some pretty badass predecessors on bass in SP, so I had to find a way to honor the history, but also stand out. I was up for the challenge, though. I feel like I did make my mark with Oceania [2012], as my style is all over that record. In general, I had to up my game or I was going to fall flat on my face. Billy was a great mentor; we had a great musical connection, and I felt trusted and respected as a player. That trust helped build my confidence in myself. I’ve taken that with me in my other projects — this idea that if I trust my instincts, they won’t lead me astray. Do you miss any elements of being in that band? Yeah, of course. I love those songs, and I

26

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

miss playing them. I miss the energy of their audience, and I had a great bond with a lot of the fans, and I miss seeing them out at the shows. I do feel like I am still supported by the SP community, which is really wonderful. Many of them have continued to follow my projects over the years. It warms my heart. Are there any bass players who have been inspiring you lately? I love watching my friend Ashley Reeve [Cher, Filter] onstage; she’s such a raw talent. And Nikki Monniger of Silversun Pickups is also amazing. My all-time faves are Simon Gallup, Peter Hook, Kim Gordon, Carlos D, Jennifer Finch, and Krist Novoselic. How have you evolved as a bass player from your early years of playing? I think it’s not only a matter of playing in so many bands, but just getting older and learning to trust my gut when it comes to musical choices. Listening to my instincts and not worrying so much anymore about what other people think are important to me now. And I’ve been lucky enough to learn personally from some of rock’s greatest artists, so I’ve taken all of those tools along with me. I’ve tried to pick up what I can along the way and just continue to learn and grow individually. It’s been a wild ride, that’s for sure. l

OFTEN IMITATED. NEVER DUPLICATED. INTRODUCING

THE PLAYER SERIES PRECISION BASS

®

NEW PICKUPS. NEW COLORS. AUTHENTIC TONE.

FRANZ LYONS OF TURNSTILE PLAYER SERIES PRECISION BASS IN BUT TERCREAM ©2019 FMIC. FENDER, FENDER in script, P BASS and the distinctive headstock commonly found

b a s s m a g a z i n e . c o m ; on Fender I S Sguitars U Eand1basses;are registered B A Strademarks S M ofAFender G AMusical Z I NInstruments E Corporation.

27

Jump Head

“I

was happy to be called to play bass — not to spin the bass around my neck or even to solo, but just to play foundational, grooving bass, which is what I love to do.” So says Victor Wooten remembering a call from Dave Matthews Band saxophonist Jeff Coffin to anchor a live recording in Nashville featuring saxophone titan Dave Liebman. On the Corner Live!: The Music of Miles Davis, with drummer Chester

Thompson, keyboardist Chris Walters, and guitarist James DiSilva rounding out the sextet, draws from Davis’ fertile 1972 jazz–rock– funk platter of the same name, on which Liebman played a starring role. The unit also covers material from Davis’ In a Silent Way and Live Evil [all on Columbia]. That meant mining the minimalist, hypnotic ostinatos of Michael Henderson. Offers Wooten, “I was familiar with Miles’ music in that era through my brothers, who were avid listeners, but I

STREET 28

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

Jump Head

Victor Wooten Revisits Miles Davis’ On the Corner With Dave Liebman & Jeff Coffin By Chris Jisi didn’t really know the players. I knew Michael more from being a pop vocalist in the late ’70s, with his hit, ‘You Are My Starship.’ He was certainly the vital backbone of Miles’ music in that period.” To prepare for the gig at the Nashville venue 3rd and Lindsley, the band received recordings and charts and had one rehearsal. “Dave likes to keep it loose, so a chart might have eight bars of a notated line and that’s it, or a little notation and then a prompt that the bass player and drummer should come up with a new groove in a specified key. I love that, because it invites the band in. Dave trusted us to provide him with quality support and inspiration.” As for his rhythm mate, Thompson, best known for his work with Phil Collins, Frank Zappa, and Weather Report — including Jaco’s debut with the band, “Barbary Coast” [Black Market, 1976, Columbia] — Wooten was hip. “Chester lives here in Nashville, so I’ve gotten to play and hang out with him a good bit. He comes from an older school of drumming that reminds me of playing with my brother Roy or Lenny White. There’s a grit and humanity in

their playing that’s sometimes missing from younger, chops-’n’-flash-oriented drummers. Their sole objective is to make the song or the soloist sound good, and there’s always a little dirt in their part that brings the emotion to the music.” Wooten is equal parts hands and ears throughout the album. He sets up a percolating boogaloo on the title track and works angular, intervallic written lines into his pulse on “Wili” (listen for his quick E-string tune-down to grab a few ultra-low notes). Elsewhere, his free-form, harmonics-infused “Bass Interlude” settles into the briskly paced, dynamic “Black Satin,” and he picks up his fretless Taylor acoustic bass guitar for the airy ballad “Selim.” Staying home on the twonote ostinato of “Ife” leads to more stretching on the experimental burner “Mojo.” Finally, his bubbling, muted-fingerstyle foray drives the album-closing “Jean-Pierre” [We Want Miles, 1982, Columbia]—a more contemporary Davis cover that boasted a young Marcus Miller. With so many of the album’s songs centered around one-chord vamps, does Wooten

VIEW

L I ST E N On the Corner Live!: The Music of Miles Davis [2019, Ear Up] Gear BASSES Fodera YinYang 4-string, fretless Taylor acoustic bass guitar STRINGS DR Strings Pure Blues PBVW-40 AMPS Hartke LH1000 head with 410 Hydrive cabinet EFFECTS Zoom B3 Bass Effects Pedal

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

29

Victor Wooten

have advice for bassists faced with similar situations, who are unclear about when to stay home on the bass line and when to improvise? “To me, there are three keys: First, don’t be afraid to play something over and over. That creates a musical mantra or trance, which is really what a groove is supposed to do. At the same time, you can’t play a repetitive figure as if you’re coasting; you have to continually add momentum and energy so the song can maintain itself and move forward. The second key is listening; if you do that correctly, the song and the band will let you know when to change or if you need to change. That kind of conversational approach will also keep the song alive. The third key is having some kind of theory knowledge to understand that just because you’re playing on one chord doesn’t

30

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

mean you can only play the root. There are seven diatonic chords in the given key to choose notes from. So if we’re in Gm, I may play and E or an A at the end of an eight-bar phrase, just to change the chord quality and throw in a different color. That’s the power of the bass: We can change the quality of the chord simply by playing a different note. As I tell students at Berklee, every instrument has a superpower. Once you learn what it is and how to use it, you become more potent as a musician.” For Wooten, the opportunity to cover the bass chair for this historic revisit was its own reward. “I got to play Miles Davis’ music with the great Dave Liebman, one of Miles’ musicians. That’s an honor that will hold a special place in my career.” l

High Powered, High End Bass Cabinets, Stereo Valve Pre-Amps, Amplifiers, Studio Monitors W J B A 2 0 0 0 Wa t t A m p W J B A 2 1 0 0 0 Wa t t A m p Ready for stadiums and the largest of club and stage gigs. Specifically designed for touring and back line requirements.

1000 watts (in bridge mode) into 4 or 8 Ohms. Packaged with similar features and controls of the WJBPII Bass Pre-Amp (single channel 6 band EQ)

“This is the best bass amp that I’ve ever played thru! OMG this new head is absolutely insane, I’m blown away. This technology is light years ahead of everyone. Thank you thank you thank you.” ~ Derrick Ray (Rihanna, Alicia Keys, Mary J. Blige) “The amp is AMAZING! It sounds so good!” ~ André Bowman (Usher, Lady Gaga, Will I Am, Black Eyed Peas)

W J B P St e r e o Va l v e B a s s P r e - A m p 5 Band EQ, Input Gain for both Passive & Active basses, Optical Compressor, Built in Tuner.

W J 1 × 1 0 St e r e o / M o n o Bass Cabinets

500 Watt a side, 4 ohm cabinets that are used as a pair in stereo or parallel mono.

W J 2 × 1 0 Pa s s i v e 7 0 0 Wa t t B a s s C a b i n e t 700 Watt @8 Ohms, Compact, High End, Crystal Clear, Full Range 2×10 Bass Cabinet (40 Hz – 20 KHz & does the job of a 4×10).

J o n e s - S c a n l o n St u d i o M o n i t o r s

With state of the art DSP, High Powered, Bi-Amped, stunning Frequency Response, incredible Phase & Time Alignment. “I first used these speakers with the Rolling Stones, there is no more demanding a situation for a speaker than reproducing a Stones tracking session at volume. They have the detail and accuracy for low volume mixing and also the power to rock the house with musicality.” ~ Krishan Sharma (engineer Rolling Stones)

W J B P I I Tw i n C h a n n e l P r e - A m p WJBPII Twin Channel Bass Pre-Amp, featuring the option of phantom power on the second channel.

“I’ve done many tours in my 40 Years of playing bass guitar. I’ve never Experienced a pre-amp like the Wayne Jones, that gives me studio dynamics live on Stage. Simply Incredible.” ~ Kevin Walker (WILL.I.AM, Kanye West, Prince, Justin Timberlake...) “Clean, clear and detailed and all the tube warmth you could ever need.” ~ Marcus Miller

W J 2 × 1 0 Pow e r e d C a b i n e t

1000 Watt Compact, Portable High End, High Powered, Crystal Clear, Full Range 2×10 Bass Cabinet (40 Hz – 20 KHz & does the job of a 4×10)

www.waynejonesaudio.com

w w w .f a c ebook .c om/ Wa y neJonesAudio

@wa y nejones aud io

Philm, Ultraphonix

PANCHO TOMASELLI Low Rider By Jon D’Auria |

R

Photo by Kevin Blades

egardless of where he is or whom he’s with, Pancho Tomaselli is always the biggest personality in any room he steps into. Whether it’s his lightning-fast wit, the abundant life lessons that he’s quick to impart, his hilarious tour stories, or the intense charisma he embodies when he sparks up a conversation, the 44-year-old has a swagger all his own. And when it comes time to step onstage, the Ecuadorian-born 4-stringer’s playing somehow overshadows his persona. That’s why legendary acts such as War, Tower Of Power, Rex Brown, Eric Burdon, Dos Lobos, Tricky, Nelly Furtado, and many others have enlisted his powerful playing for their music. Tomaselli moved from Ecuador at age 20 to attend the Berklee College of Music, but not to study bass. Instead he graduated with a degree in Music Business and Management. From there he moved to Los Angeles, where he landed a high position with Virgin Records in its A&R department, which led him to work with Janet Jackson, the Rolling Stones, Lenny Kravitz, Ben Harper, and a slew of others before he got the itch to jump to the other side of the desk to pursue music once again. Several bands instantly recruited him before he got the call to join War, a bass chair he proudly held for 16 years. This eventually led to him stepping in for Rocco Prestia in Tower Of

32

Power for a series of tours in 2013. From there, Tomaselli decided to create his own music. That’s when he helped form the rock trio Philm, featuring drummer Dave Lombardo (Slayer) and guitarist Gerry Nestler. Now sans Lombardo, Philm is preparing to release its third album, Time Burner. The release will coincide with the debut album, Original Human Music, from his other outfit, Ultraphonix, a hard-hitting rock supergroup that features Corey Glover (Living Colour), George Lynch (Dokken), and drummer Chris Moore. When he’s not occupied with those bands, Tomaselli is keeping busy writing original music and scores with his old mates from Dig Infinity and putting the finishing touches on his new signature-series basses from G&L Guitars. “I’m always busy, because I’m willing to work harder than anyone else,” says Tomaselli. “Aside from that, I’m just a shredder bass player who never plays roots and 5ths and was blessed with chops and a good ear.” ow do you prepare for all of these big gigs that you land? I’m the type of player who is called to come in and fix holes. When I got the War gig, I looked at what B.B. [Dickenson, founding bassist] wore to the shows, what he smoked before the gigs, where he was from, what he ate, what his amp settings were, what bass he was playing — I would go deep into the psy-

H

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

33

Pancho Tomaselli

L I ST E N Philm, Time Burner [2018, philmofficial. com]; Ultraphonix, Original Human Music [2018, Edel Germany] EQUIP BASS G&L SB1 P-style, fretless Kiloton, JB 4-string, and LB100 RIG Form Factor BI1000 head, Form Factor 2B-10L and 1B15L cabinet PEDALS Line 6 Helix, Gogo Tuner STRINGS D’Addario Medium Half Rounds (.050-.105)

34

chology of the gig. Anyone can play the notes; notes are just notes. But the true pros pay attention to the details and absorb all of the parts of the role. When I was playing for Rocco in Tower, I went to ESP and told them to set my action how Rocco had his on his basses. So they mailed me a P-Bass, and the action was set so damn high. That’s the only way you can play that many 16th-notes without being wobbly. It’s all in the high action. But that’s a detail that could’ve been overlooked if I hadn’t searched it out and replicated it authentically. How did get the opportunity to play in Tower Of Power? I got a message early one morning from [drummer] Dave Garibaldi that said to call him immediately after I finished my huevos. So I did, and they told me Rocco was having some health issues. The first concert was that week and I had to decide immediately if I would take it. It was a no brainer. The craziest thing about that gig was that I had no rehearsals with them, and I had never played a note with the band before those tours. I don’t do covers in my personal practice, so I had never played any of that music whatsoever. The first time I ever played “What Is Hip” was onstage with Tower for a packed crowd. It was a wild experience. It was definitely the biggest challenge and the most daunting thing I’ve done in my career. It was like Rocco and Garibaldi and the whole world of funk was asking for my help, and I had to step up to the challenge. Why did you study business instead of bass at Berklee? I studied music business because it was the only way I could get funding for it. But that’s probably what made me so directed in my career. If I had studied bass at Berklee, I’d probably show up to all of these gigs with written charts, a 6-string bass, and I’d probably slap and tap all over the place. But instead I came into this business playing with street cats like War and Dos Lobos, where they just shut up and play. And they do it really damn well. How did you go from being a major-label A&R person to playing in War? My first gig back was playing cumbia mu-

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

sic in a band called Sonora Dinamita, which was great because it was a familiar sound to me, so it was easy for me to get back into the swing of being a professional musician. Then I got the call from War. I really didn’t understand how iconic and how big War was when I joined them. Musically, they taught me how to play. Everything I know as a bass player I learned from that gig. And it wasn’t just funk — we’d play all types of music. I held that bass chair for 13 years and loved it. What’s a specific lesson that you took away from that band? One big thing that I learned from War is that a mistake is only a mistake if you make an obvious face and then you don’t repeat the mistake again. If you mess up and shrug or look at someone else, then everyone will know you messed up. Just keep your head down, play the same wrong note again and then laugh with the band about it later. You see, War is all ghetto players, so they know the little secrets of music. What can we expect from the new albums coming out with Philm and Ultraphonix? The Ultraphonix album was so great to make. We got together and wrote a bunch of songs, and it’s all super bass heavy. After I finished tracking, I called Juan Alderete [Mars Volta, Racer X] and told him that I jacked his moves on this stuff. With Philm we lost Dave Lombardo for this album, so Gerry Nestler and I wrote a new album, and now we’re going to release it and play some shows. It was a one-take album where we just went in and tracked quickly and put vocals on top of it, and I’m so excited for the world to hear it. It’s our best music yet. What’s your best advice for working bassists? More than ever, right now is the time to really be yourself and stay off the trends. Famous people are so damn famous now that if you do what they’re doing, you won’t make it. By the time you get noticed, everyone will be on to the next fad. Don’t chase all of that; just be yourself. I’ll always just be me. I play a 4-string bass with dead strings, and if you like it, call me — and if you don’t, I’ll find another gig. No biggie. l

Pancho Tomaselli

JARED SCHLACHET

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

35

ADELINE 36

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

FINDING HER VOICE By Bill Leigh | Photos By Dennis Manuel

T

he stars seem aligned for Adeline. Since moving to New York from Paris 14 years ago, the singer/bassist fronted two albums with slick 17-piece disco throwback band Escort, including a self-titled debut, which made Rolling Stone’s top 50 albums for 2012. Then there was a two-year stint playing on NBC’s Meredith Vieira Show, which led to a bass-and-backing-vocals gig with singer CeeLo Green. Now with her debut album, Adeline [ad-uhleen] — a funky outing influenced as much by Prince as by the Caribbean music of her father’s native Martinique — Adeline is coming into her own as a solo artist. “I was always writing my own stuff,” she says. “It just seemed like a natural evolution as an artist.” Finally releasing her first solo album required a bit of a psychological “push,” as Adeline describes it. “I was a huge fan of Prince, and when he died I was devastated. People I met who had worked with him told me, ‘He’d love you,’ so his death kind of selfishly shattered my dreams of someday collaborating with him. But I was also inspired, because Stevie Wonder spoke about how fearless Prince was in his music, and that if you introduce fear into yourCaption music, you cease being creative. That hit me so hard; I realized I’d been afraid of doing this solo stuff, and I had no more excuses. So I just went for it.” Adeline had been a touring singer even as a child, and she took up guitar at age 15 to begin writing her own songs. Bass entered the picture shortly after she moved to New York, when a hired bassist cancelled the day before a gig, and her bandmates encouraged her to play bass. “I totally fell in love with the way it felt on my fingers, the way it sounded, the feel, and

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

37

Adeline

just the attitude and everything about it. It was like, Oh my God, that’s what I was looking for.” Once hooked, Adeline locked herself in her apartment for a year of intense practice. “I was lucky to be surrounded by some amazing bassists who could show me things,” she explains. Chief among her bass mentors was Fred Cash Jr., son of Impressions co-founder Fred Cash Sr., who had himself been mentored by Impressions and Curtis Mayfield bassist and music director Joseph “Lucky” Scott. “‘Super Fly’ was one of the first big songs I had learned; I’m a huge Curtis Mayfield fan and was really drawn to Lucky Scott’s sound. So my mentor was mentored by my favorite bass player.” Adeline’s bass influences can be heard all over Adeline [ad-uh-leen]. There’s the Lucky Scott-style R&B syncopation driving “Never Know” and the disco octaves and hammer-ons of “Before”; the stuttering Bernard Edwards-meets-Jamiroquai pulse of “Echo”;

38

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

the taut, pocketed slaps anchoring “Emeralds” and “Café Au Lait”; and the greasy hiphop subhook of “Satellite.” She’s also inspired by her contemporaries, like Alissia Benveniste [Bootsy Collins] and Brooklyn-based doubler Burniss Earl Travis II [Common, Robert Glasper]. Vocally, Adeline pays close attention to other bassists who sing. “Meshell Ndegeocello is my favorite, and I also love Larry Graham’s work with Graham Central Station. In terms of singing and playing, technically, Esperanza Spalding does it at the highest level.” So how does Adeline approach playing and singing at the same time? “When I started playing bass, I learned the parts for songs where I was already singing. So I was already thinking of bass as an accompaniment to singing, but it’s still extremely challenging. I realized that it was taking me like five times longer to learn a song than other people, because when you’re singing and playing, you’ve got to run it over and over. Now it’s

Adeline

just part of my process. One trick I use when the rhythm of the vocals and bass are different is to count out the bass-line rhythm slowly with a metronome until it becomes second nature. Then I place the words in the rhythm. But that’s why I enjoy playing for other people also, because I’m a bit freer on bass when I’m not singing at the same time.” When it comes to refining her musical voice, Adeline also focuses on getting a good bass tone. Her tools include Sadowsky basses and Aguilar amps. “Both Roger Sadowsky and the guys at Aguilar set me up in style for Meredith’s show, and they continue to provide amazing support,” she says. Underfoot,

a favorite is her Aguilar Filter Twin. “That’s the one I really like. I use it for Bootsy Collins moments of slap with filter effects.” She continues, “I’m a huge fan of Meshell’s sound, and the last time I saw her play, it made me understand that I needed to spend some time on getting my bass tone, so that’s what I’ve been working on since my last tour. I just spent more time getting the sound right in soundcheck and in band rehearsals.” Adeline’s bass tone philosophy is simple: “I really want to get my tone to be like a second voice, besides my singing voice. People focus on my voice because I’m a singer, but I want to have a pretty voice with my bass, too.” l

L I ST E N Adeline [ad-uh-leen], 2018 GEAR Basses Sadowsky J-Basses Strings Sadowsky Blue Label stainless steel (.045–.105) Amps Aguilar DB 751 head with DB 810 cabinet; Tone Hammer 500 head with SL 112 cabinets Effects Aguilar Filter Twin, DigiTech Bass Whammy, Boss Super Octave

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

39

Jump Head

40

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

5-String Superhero By Jon D’Auria

AS

with most children growing up in Osaka, Japan, the scope of Kiyoshi’s musical world as a young girl revolved around Japanese pop music and Anime theme songs. She took piano lessons regularly from a budding age and would contently sing along with her favorite songs on the TV and radio when she wasn’t immersed in her studies. Her modest taste in music, however, took a vast turn when she turned 15 and learned about the exploding alternative rock scene of the ’90s that was going down in America. All of a sudden her taste in music shifted from regional genres to the booming music of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Rage Against The Machine, Mudvayne, Fishbone, 311, and especially Primus. Realizing that a common theme among these bands was their prominent use of bass, Kiyoshi quickly ditched her piano studies and bought a 4-string that became her new obsession. She submersed herself into the instrument, and by learning songs by the bands she adored, including the slapping and tapping lines of Les Claypool, she eventually became a hot commodity in the music scene around her. By also teaching herself how to sing while playing, she began writing her own songs, which led her to join Japanese rock bands Madcap Laughs and Inside Me, as well

as appearing in the 2016 Japanese movie Too Young to Die. Once she felt she had found her unique musical voice, Kiyoshi wrote her own solo material, which led to her 2016 release, Kiyoshi, and her sophomore follow up, 2017’s Kiyoshi2, which both feature her covering all the musical parts minus drums. These albums caught the attention of former Megadeth guitarist Marty Friedman, who enlisted her as the touring bassist for his band. At this time she also caught the attention of Warwick Basses, who brought her on as an endorsee and made her own series of Streamer basses. In 2018, Kiyoshi released her third solo album, Kiyoshi3. It features her honed playing and tenacious slap chops, which kick off the album on the song “Hero,” and continue the sonic attack with her dirty tone and fast wrists on “Sign” and “Escape.” Gaining attention from reaches of the globe far from Japan, Kiyoshi’s musical journey is gaining steam more than ever before. And much like her slap riffs, it’s showing no signs of slowing down.

W

hat was the writing process like for Kiyoshi3? Since about 2016, when I released my first album, making songs has become much faster, and I always knew that I wanted to do this two-piece band someday.

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

41

Kiyoshi

L I ST E N Kiyoshi, Kiyoshi3 EQUIP BASSES Warwick Streamer Stage II 5-string, Streamer Stage I 5-string, Thumb Bass 5-string RIG Gallien-Krueger 1001RB II, SWR Goliath III, SWR Big Ben 2x15 EFFECTS Fulltone Bassdrive, MXR M-80 Bass D.I.+, SansAmp Bass Driver DI, EBS MultiComp, Electro-Harmonix Micro POG, Electro-Harmonix Pitch Fork, Boss Harmonist STRINGS D’Addario Medium 5-string

42

I write all of the songs and arrange them and play all the sounds except drums, so it is very quick to complete them. It is not necessary to think about guitarists, keyboardists, and other instruments. Thinking only about the most important rhythms and melodies, making songs with few instruments is very free and a lot of fun, and the ideas spill out rapidly. It was smooth and easy to make three albums because of that. How do you typically write your songs? Does it always start with a bass riff? I often hum while playing the bass, so the song will be completed naturally because my lines and vocals come about at once. I keep a lot of stock of riffs and melodies that I’ve made in the past few years, so sometimes I connect them and complete them by piecing them together to form full songs. How would you say Kiyoshi3 is most different from Kiyoshi and Kiyoshi2? My first album is a work with many experimental elements. Everything was my first experience; it was my first time creating an album with just drums and bass, and it was also my first time singing by myself. When I listen to it now, I feel that my voice was so weak and thin, and that the sound was crude, but I do like its passion. The sound I wanted was clarified with Kiyoshi2. I aimed for a very intense, clear, and vivid bass and drum sound. It incorporates a wide range of music genres, from my favorite ’90s alternative vibes, pop themes from the ’80s, rhythms like U.K. rock bands, and lots of other elements. In Kiyoshi3, those elements are getting stronger. I think that my performance and sound are the highest quality they’ve ever been. The biggest difference is that my singing has become a much stronger presence. I’m very glad that my voice has become so powerful. I hear some Les Claypool influence in the riffs of “Hero” and “Escape.” He is my superhero! He is my favorite bassist in the world. I have all of his albums, and I learned a lot of his riffs. It was a shock when I listened to Primus’ “Tommy the Cat” for the first time. “What is this sound? How does he move his hands like that?” I

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

watched the video over and over and practiced. I learned from him how to slap, like I do in “Hero.” His songs are perfectly complete with only the bass riffs. He taught me that bass can support songs, but it can also be the song’s main element. You play some great chordal parts in “Mirror” and “Stay.” My band is only my drummer and me, so sometimes my bass plays the role of guitar. I can’t play the guitar, but I play like a guitarist on bass sometimes. I wrote “Stay” as if I were playing an acoustic guitar. I like the resonance of the bass chords very much, but when playing too many strings at once, sometimes the sound becomes muddy. So mostly I only strum two or three strings at a time. I like playing the root note with the 4th string and chords with 1st and 2nd strings. Your style shifts a lot from rock to heavy to progressive to alternative. How would you describe your music in your own words? I love the beautiful melody of the Japanese music I grew up listening to. I like to sing super-catchy melodies on funky and heavy bass riffs. It would be wonderful if I could rap like Zack de la Rocha or scream like Jonathan Davis, but I can’t. But luckily I like my innate voice now. What is your ideal bass tone, and how do you achieve it? I like both super-distorted and clear sounds. In recording, I make both a very clear sound and a very distorted sound, and I mix them together at different parts. The allocation of clean and distortion is changed by what the song calls for exactly. You get a great slapping sound. Describe your technique. I actually slap the strings pretty softly. I’ve learned that you don’t need to bang on the strings to get a big sound. Sometimes it feels like I’m simply placing my finger on the string when I slap. Sometimes I swing my arm a lot and do big arm actions, but the moment I touch the strings I’m gentle. That part is just for show and being in the moment of the performance. Why do you prefer 5-string basses?

OPEN A

AND CREATE THE FUTURE OF MUSIC.

MIXING YOUR LOVE FOR MUSIC WITH YOUR BUSINESS IS EASIER THAN EVER AT SCHOOL OF ROCK. BE RESPONSIBLE FOR CHANGING THE LIVES OF CHILDREN THROUGH MUSIC EDUCATION. OWN A SCHOOL OF ROCK FRANCHISE TODAY.

CONTACT US TO LEARN MORE. 866-957-6685 FRANCHISING.SCHOOLOFROCK.COM 43

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

Kiyoshi

I like playing heavy rock, so I need the low B or low A. The possibility of my bass lines expand with that extra string. The 5-string has narrower string spacing than a 4-string, so

44

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

it’s also easy for me to strum chords on them. What do you love about Warwick basses? Most of my favorite bassists are playing Warwicks — P-Nut, Norwood Fisher, Ryan

Kiyoshi

Martinie, Robert Trujillo, and so many others. The Warwick bass sound is very clear without being buried, even in intense music. Becoming a part of the Warwick family was my dream. Two years ago the dream came true! Now Warwick makes basses for me. I still can’t believe it. You started playing bass at age 15. What led you to choose bass? I wanted to listen to more music and began to explore music from all over the world. My preference for music changed more and more to heavy things. Rap-rock and funk-metal was music I had never heard before, and there were incredibly cool bands that changed my life. The thing that always stood out for me was the bass player. I was amazed that various sounds were coming from the bass, and I felt that the bass, universally, was the source of the groove of music. That’s when I decided to pick up the bass. Was it natural for you to play bass in the beginning? It came very naturally to me. I could not think of anything I wanted to do other than play bass. But in fact, my first dream about the bass was not to become a bass player, but to become a bass builder. My interest in the bass became very deep, and I wanted to make this instrument with my own hands. I wanted to be a craftsman like Carl Thompson. I went to a school where I learned how to make musical instruments, and I made a lot of basses. It was a very fun time, but I quickly learned that it is more fun to play the bass than it is to make them. What was the first bass you owned? It was an ESP Guitars 4-string, “Forest.” I bought the same one as the bass player of my favorite Japanese rock band, L’Arc-en-Ciel. I learned all of their music by playing with a pick, but now I don’t use picks anymore. Has it always been easy for you to play bass and sing at the same time? Not at all. At first it was very difficult, but I got used to it after practicing it a lot. Before standing on the stage, I know the bass lines in and out and don’t have to think about them so that I can concentrate on singing.

Your live shows are very energetic and powerful. What’s going on in your mind when you play? I don’t think much about what I’m doing. I throw myself into the music, and the music will guide me. I’m not thinking, “Let’s shake my head here, let’s jump here,” and so on. If I play like my bass is coming from my body, not from the speaker, it will be a great show. I sometimes get nervous or lose confidence before a concert, but the moment I stand on the stage, the audience turns on my switch. They make me a superhero. When I play onstage, I believe that I’m a great bass player. I think that is common courtesy to the audience. What’s it like playing with Marty Friedman? He somehow plays the guitar as if he is singing through his instrument, so I feel like I’m playing with a singer when we’re onstage together. What he does on guitar is so amazing, I can just sit back and play eight root notes and it still sounds good. He is a perfectionist — he has mastered so many difficult techniques — but onstage he emphasizes the band’s groove and passion more than technique, unlike a lot of players. What do you like most about his music? I like his super-heavy riffs, and also his beautiful ballads. He has an open mind to music and incorporates music from various countries into what he writes. He keeps making great music, and I am amazed by his willingness to create. He is not only a great guitarist but also a great songwriter. You play very physically. What’s your preshow routine? I do yoga and light exercise such as pushups to warm my body. Then I play the bass and move my fingers with simple basic practice. That usually loosens me up and makes me feel ready. Why the bass? What do you love so much about the instrument? Well, simply put, the bass is extremely cool [laughs]. I don’t know how else to say it. The sound of the bass has made my musical world vaster and my life better. I would like to say “good job” to me at age 15 for choosing this instrument. l

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

45

LARRY

GRENADIER’S THE GLEANERS On his new ECM album, alternate tunings, Oscar Pettiford, Anton Webern, studio techniques & the loneliness of recording solo By John Goldsby |

L

egends Gary Peacock, Dave Holland, Miroslav Vitous, and Barre Phillips have graced the bass world with their solo recordings on the ECM label since the ’70s. Now Larry Grenadier joins the ranks of these celebrated players with his own set of brilliantly conceived and impeccably executed solo double-bass tracks, The Gleaners [2019, ECM].

46

BASS MAGAZINE ; ISSUE 1 ; bassmagazine.com

Photos by Juan hitters, ECM Records

Grenadier’s intonation, tone, and expressiveness is quite an achievement, and it’s one of the best records in its category that I’ve heard in a long time. I first met Larry in the early ’80s at a jazz workshop in San Jose, California. He was a workshop student, about 15 years old, and I was 22 — a fledgling teacher. I remember sitting with my clinician colleague Todd

bassmagazine.com ; ISSUE 1 ; BASS MAGAZINE

47

Larry Grenadier