6 minute read

Carbon Conundrum

BY SAM BARNES

Permitting delays and emerging community battlegrounds are slowing the ‘gold rush’ for capture, usage and storage.

Agrowing number of carbon capture and sequestration projects are at the proverbial starting gate in Louisiana, but the Class 6 permits needed to store the substance remain in limbo.

Adding insult to injury, the state’s efforts to gain regulatory primacy over the permitting have stalled, a full year and half after the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources submitted the request to EPA’s Region 6 headquarters in Dallas.

Giving Louisiana primacy would “most definitely speed the process,” says Patrick Courreges, communi- cations director at the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources. “We are still waiting for any type of word, whether an approval, denial or even feedback. Last summer, it moved from the regional office to EPA headquarters for review, and that’s where it still sits. We’re not getting any updates or timetables.”

The permitting logjam has delayed billions of dollars in potential CCUS (Carbon Capture, Utilization and Sequestration) investment.

According to EPA’s Region 6, there are currently five companies with pending Class 6 permits at proposed Louisiana sequestration sites: Oxy Low Carbon Ventures LLC in Allen Parish, Gulf Coast Sequestration in Calcasieu and Cameron parishes, Hackberry Carbon Sequestration LLC in Cameron Parish, Capio Sequestration LLC in Pointe Coupee Parish and CapturePoint Solutions LLC in Rapides Parish.

That’s frustrated Gov. John Bel Edwards, who in January criticized the slow playing of the process in a letter to EPA Administrator Michael Regan.

“More information on the progress of Louisiana’s Class 6 application would help encourage potential CCS operators to make firm investment decisions,”

Edwards says in the letter. “We are now seeing concepts begin to turn into investment decisions, but a recurring question is if and when Louisiana will receive primacy.”

DNR Secretary Tom Harris reiterated frustrations over the process during the Louisiana Oil & Gas Association’s recent annual meeting in Lake Charles. “Nationally, the EPA has issued only six Class 6 permits in six years’ time, none of which are in Louisiana,” Harris says. “That’s not a time frame where businesses can make final investment decisions with any confidence. Companies deserve a faster turnaround.”

Giving LDNR regulatory primacy could help free up the backlog and catapult Louisiana into a regional CCS leader, Harris says, given the state’s existing pipeline infrastructure, petrochemicals industry concentration and geological storage locations.

“It seems like a custom-built opportunity with immediately recognizable benefits,” Harris adds. “Over the past several years, we’ve seen stepped up interest in the concept of CCS, with companies making real investment decisions toward turning carbon management into reality.”

To date, DNR has received Class 5 permits for injection well tests (often a necessary precursor to a Class 6 permit) from Louisiana Green Fuels in Caldwell Parish, Capio in Pointe Coupee Parish, Oxy Low Carbon Ventures in Allen and Livingston parishes; Air Products in Livingston and St. John parishes, Shell in St. Helena Parish, CapturePoint in Vernon Parish, River Parish Sequestration in Assumption Parish and Denbury Carbon Solutions in Ascension Parish.

If and when it gains primacy, DNR plans to triple the size of its regulatory staff from three to nine to prepare for the initial rush in applications. “Louisiana is pretty unique, and we have the knowledge of our geology,” he adds. “There are more time efficiencies, too, because we have more people to dedicate to that. Region 6 only has so many people to cover four different states.”

Eric Smith, director of the Tulane Energy Institute in New Orleans, blames politics for the delays. “They’re concerned that states such as Louisiana and Texas will minimize the risk and proceed to do what they want to do,” Smitha adds. “I don’t think that’s likely. We have a pretty good safety record with that kind of thing, and we very rarely have problems with pipelines.

“You’ve got all this money waiting to be spent but no one can spend it because the government won’t get out of the way. My guess is that they’ll slowly turn over primacy to states that are loyal to the administration.”

Concerns over the sequestration piece of the puzzle might be part of the reason for the delays. “The big prize that everyone is after, including the federal government, is drilling these Class 6 wells into saline aquifers deep below the surface, then pumping the carbon into those,” he adds. “They’re virtually everywhere if you can drill deep enough.

“The problem is we don’t have reams of data on that. The concern is that the carbon will perambulate until it finds a fault line or old well and emerges at the surface.”

The

LOW-HANGING

Fruit

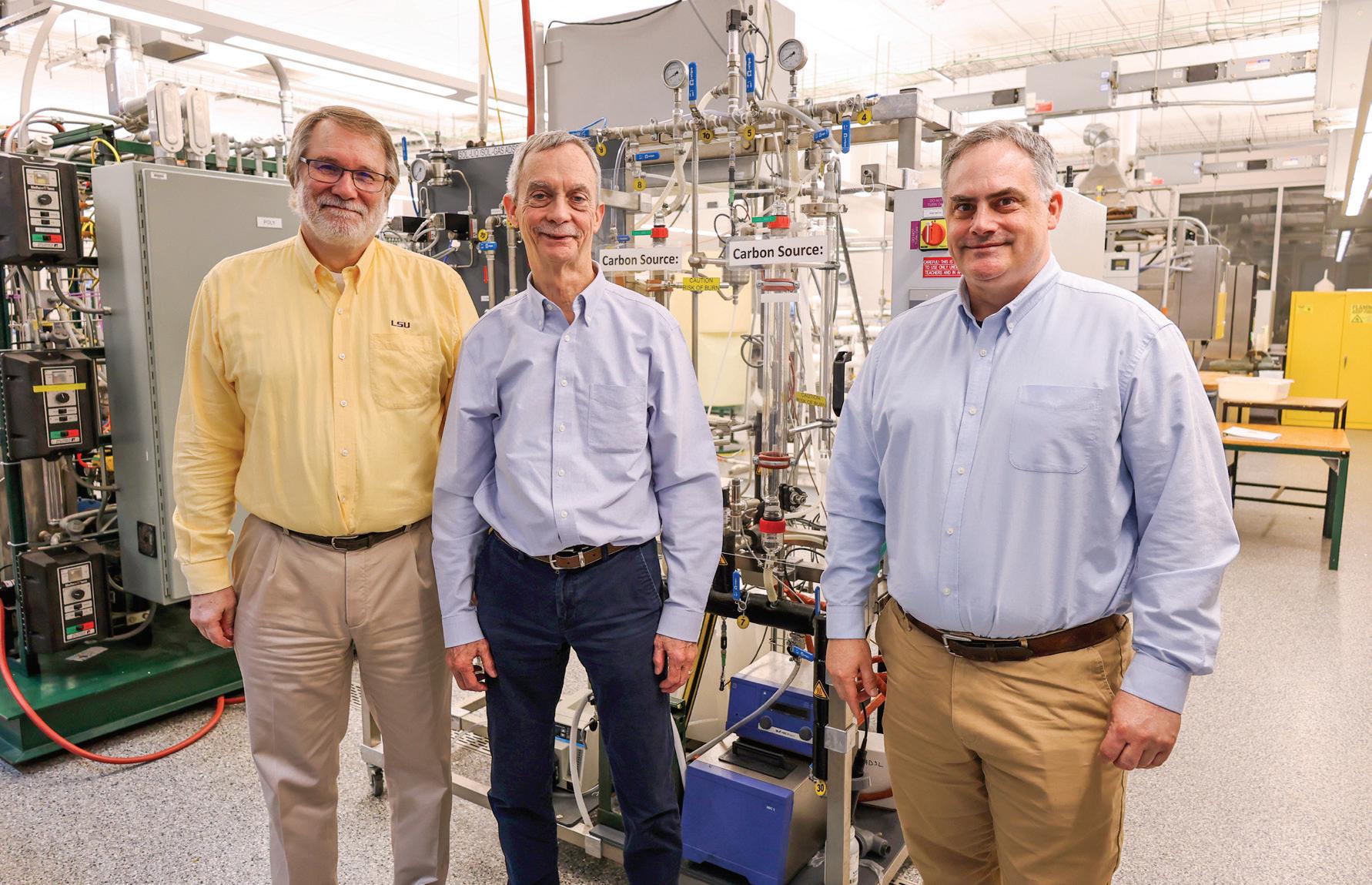

A cadre of LSU professors researching CCUS say a “gold rush” is coming, once permits begin getting the green light, fueled by government carbon tax credits. The 2022 changes to Section 45Q of the U.S. IRS code provide up to $85 per ton of carbon permanently stored and $60 per ton of carbon used for enhanced oil recovery or other industrial uses.

“My guess is that it would only cost between $5 to $10 per ton for sequestration at a site, but the credit is about $85 per ton,” says John Flake, professor of chemical engineering. “The gold rush is coming if you have a place to sequester.” What’s more, Louisiana’s existing network of pipelines can be used to transport the carbon to a sequestration site.

But Flake, along with John Pendergast, a professional in residence in the Department of Chemical Engineering, and Dick Hughes, a professional in residence in the Department of Petroleum Engineering, say it’s not all about money. The environmental benefits of carbon capture – particularly in the greater Baton Rouge area –can’t be ignored.

The “low hanging fruit,” they say, is the abundance of large-scale chemical plants that are already removing carbon as part of their processes.

“The production of ethylene oxide and ammonia already requires the removal of carbon dioxide, whereby it’s stripped out of the solution and vented as pure carbo dioxide,” Flake says. “That’s done every day within 50 miles of the LSU campus.”

CF Industries’ Donaldsonville plant, for example, is the world’s largest producer of ammonia. “They have to remove that carbon, and it’s an enormous amount,” Flake says. “That one plant is likely already removing 10 billion kilograms of carbon per year.”

Refineries and power plants, on the other hand, face a much higher barrier to entry. That’s why most of the initial investment will be focused on those plants already stripping the carbon from their processes.

“It might cost a power plant 30 percent of its power production to do that,” Pendergast says. “They’d spend hundreds of millions to billions to capture the carbon, and it would cost them about a third of your power. There has to be an additional incentive there, above the $85 per ton credit.”

As for the sequestration of the carbon, Louisiana has an abundance of geological formations already available. While depleted oil and gas reservoirs could be used, Hughes says, “the problem is that we have a lot of wells at those locations and those are usually potential leak sites. We typically avoid those.”

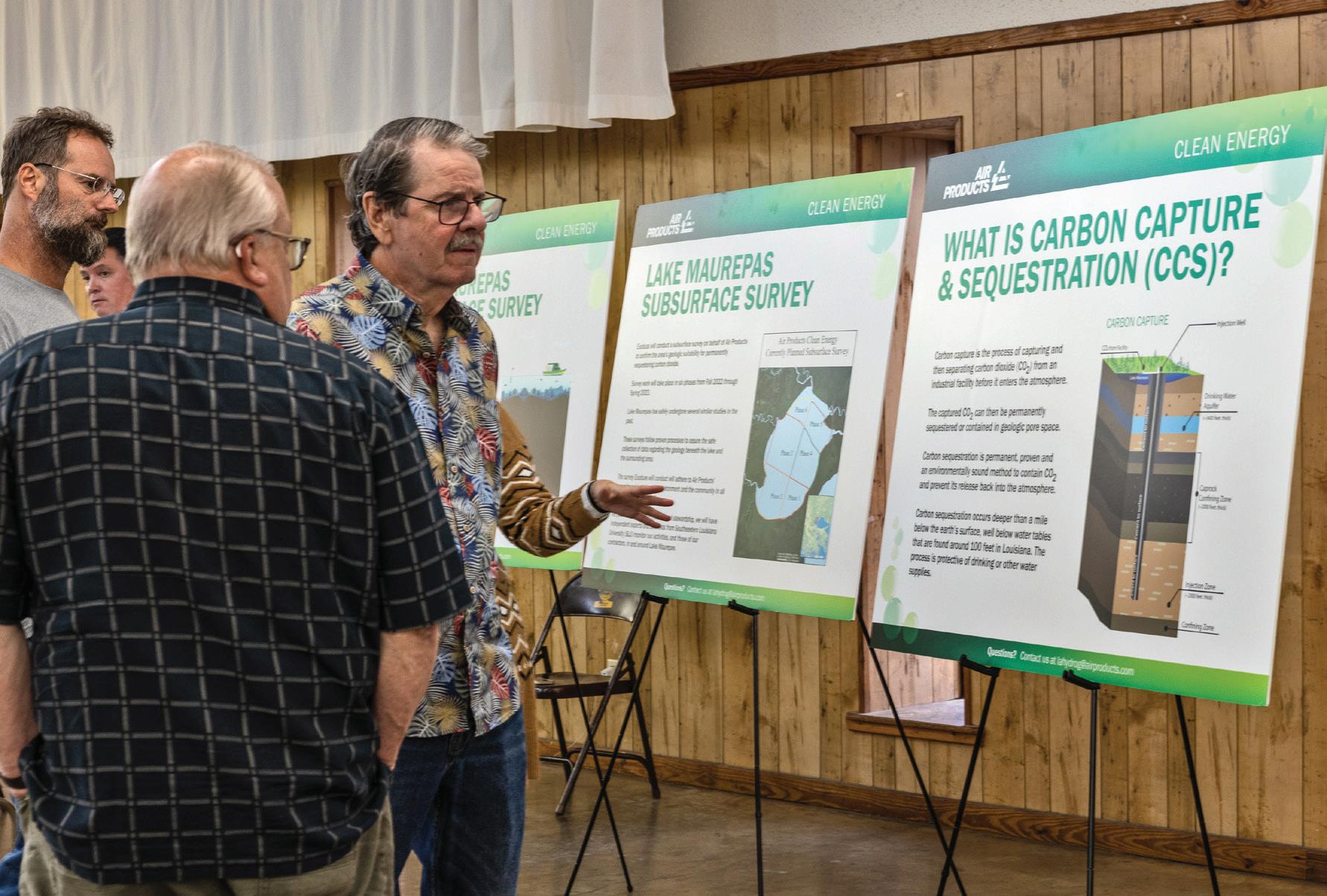

Most developers are instead seeking saline or brine formations. “Lake Maurepas is an interesting location,” Hughes says. “It has few well penetrations and the geologic environment is relatively flat. It also has high porosity and permeability, which means the amount of carbon you can inject is higher.”

Flake says the utilization of captured carbon as an alternative to sequestration remains in its infancy. “That’s more research and less application at the moment,” Flake says. “There’s no commercial utilization process at large scale.”

He’s most excited about the potential of carbon as a low-cost fuel source. Flake is researching ways to utilize carbon dioxide as an alternative fuel in the conversion of ethane to ethylene, which is used in everything from plastic products to clothing to detergents and hand soaps.

“With ethane, you’re already using a fossil fuel (ethane is derived from natural gas), then you have to utilize a lot of energy to convert it to ethylene,” he adds. “For every kilogram of ethylene you make, you generate about a kilogram of carbon.”

The goal, therefore, should be to capture and utilize carbon as a feedstock. While that currently is an expensive proposition, Flake says there could be other methods of utilization not necessarily derived from an industrial process.

LSU recently received $5 million of a $50 million grant from the U.S. Economic Development Administration grant to research and develop a clean hydrogen cluster in south Louisiana, of which Flake’s department will receive about $3 million for researching carbon utilization.

Department of Natural Resources, on Louisiana’s efforts to gain regulatory primacy over permitting from the Environmental Protection Agency

At The Starting Gate

Meanwhile, several projects are at the starting gate and ready to pull the trigger if and when their permits are approved. Most prominently, CF Industries entered into a largest-of-its-kind commercial agreement in 2022 with ExxonMobil to capture and permanently store up to 2 million metric tons of carbon emissions annually from its Donaldsonville manufacturing complex.

In preparation, CF Industries is building a $200 million carbon dehydration and compression unit to enable captured carbon to be transported and stored. ExxonMobil has also signed an agreement with EnLink Midstream to use the pipeline company’s transportation network to deliver carbon to permanent geologic storage in Vermilion Parish. Startup for the project is scheduled for early 2025.

C. Blake Phillips, senior manager of carbon solutions at Dallas-based EnLink, says his company’s existing 4,000 miles of