4 minute read

It’s academic!

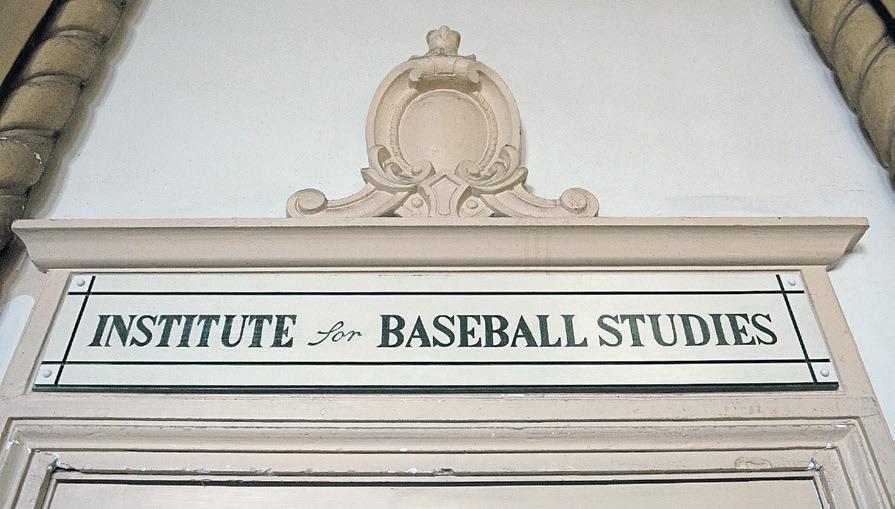

The Institute for Baseball Studies at Whittier College teaches

STORY BY JOHN METCALFE PHOTOS BY JIM ALEXANDER

Babe Ruth was a world-class player in a couple of senses. When he wasn’t hitting grand slams, he was playing the, er, field. Evidence of his dalliances can be found in Southern California’s Institute for Baseball Studies and Baseball Reliquary — a half-smoked cigar Ruth supposedly left in a Philadelphia brothel in 1924.

“That evening, a Yankee player observed Babe sitting in a big chair in an upstairs room with a brunette on one knee and a blonde on the other,” the exhibit informs. “As the girls poured a bottle of champagne onto his head and shampooed his hair with it, Babe smiled and exclaimed, ‘Anybody who doesn’t like this life is crazy!’ The next afternoon at Shibe Park, the Bambino, with barely two hours sleep, hit a pair of home runs.”

Whittier College’s Joseph L. Price, a professor emeritus of religious studies, is the director of the on-campus Institute for Baseball Studies.

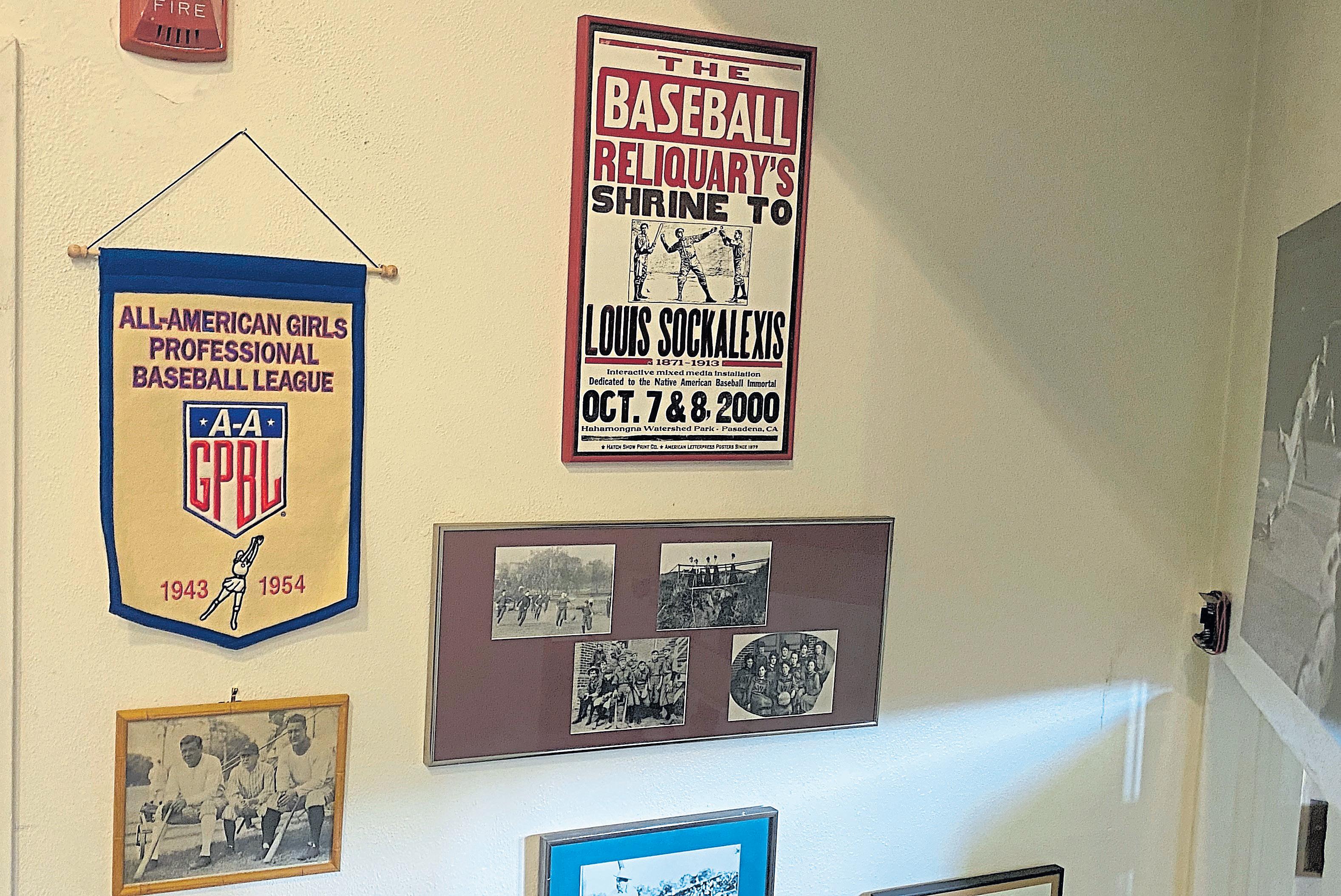

The institute and the Baseball Reliquary are full of such wonderful nuggets of history. Two separate collections sharing the same space at Whittier College, the troves include rare material on the Negro Leagues and early Mexican-American baseball, memorabilia like the costume of the San Diego Chicken and intriguing artworks, such as Darryl Strawberry’s head sculpted in chewed- up Bazooka bubblegum.

On some days, the collections include the physical presence of director Joseph Price himself. A professor emeritus of religious studies, Price founded the institute in 2014 with two other Whittier professors, Michael McBride in political science and Charles Adams in English. While it’s hard to say who’s the bigger fanatic among them, Price has good qualifications: He’s sung the national anthem at 120 major and minor-league ballparks in 42 states.

When asked why it’s important to preserve the history of baseball, Price has a simple answer.

“Baseball helps to bring people together, especially in an ethos such as ours today, when there’s divisiveness in the nation,” he says. “Baseball is one of the ways that people of different racial groups, economic backgrounds and political persuasions can sit side-by-side and cheer for the same team. They can have conversations that transcend their otherwise seemingly potent differences.”

It was not easy convincing the college administration it needed a baseball institute. “They thought it was a wacky idea, but we persisted,” recalls Price. The higher-ups relented after realizing it would keep the professors active on campus post-retirement. The trio stocked the third floor of an administration building with their personal baseball libraries and also absorbed the materials of the Baseball Reliquary, a peripatetic museum of odd parapherna- lia operated by Pasadena’s Terry Cannon, who died from cancer in 2020.

At the 2015 grand opening was none other than California Rep. Linda Sánchez, who invited herself as a huge baseball fan and player. This year, she was named coach of the congressional baseball team for the Democrats, the first woman to hold that position.

“For many of us, especially for someone like me from a big baseball-playing Latino family, (the sport) is a connection to our heritage and our past. It is a connection to memories we have playing the game with loved ones or huddling around the radio on a Sunday afternoon to hear Vin Scully call the game,” Sánchez says via email. “That is why the baseball institute and the Baseball Reliquary at Whittier College is so important — it helps us preserve those memories and helps us make new ones with our own kids.”

The institute is unique in America. Unlike the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, it infuses baseball studies into an entire college curriculum. Courses that Whittier has offered include “Muscular Faith,” about the intersection of sports and god, and “El Beisbol: A Caribbean Religion,” which has sent students to Cuba and Puerto Rico. Graduates sometimes go off into baseball-related fields — one did public relations for the Omaha Storm Chasers; another serves as director of sports science for the San Diego Padres.

Visitors to the institute will be struck by its neatly ordered shelves of 4,000 books, many so rare they’re not categorized by the Library of Congress. There are bobbleheads and paintings of Tommy Lasorda and a monkey-skull baseball, a reference to the “Death Pitch” that killed Ray Chapman of the Cleveland Indians. There’s a baseball signed by Hillary Clinton and another (fake) one by Mother Teresa, part of the FBI’s “Operation Bullpen” against counterfeit-memorabilia dealers. There’s a potato that the minor league’s Dave Bresnahan sneakily threw to try to score an out (the ruse didn’t work), and resting in the archives, an old hotdog without bun reportedly half-eaten by Babe Ruth.

Some of the most fascinating things aren’t physical. For two decades, the Baseball Reliquary has maintained an alternate hall of fame called the Shrine of the Eternals, whose members are elected often for reasons unrelated to stats or playing ability. Ted Giannoulas, the San Diego Chicken who popularized mascot culture, is in the shrine, as is Frank Jobe, the doctor who pioneered Tommy John surgery; Max Patkin, the “Clown Prince of Baseball”; sports broadcaster Bob Costas and Charles Schulz of “Peanuts” fame.

Left: Memorabilia on display at Whittier’s Institute for Baseball Studies includes much of the Baseball Reliquary collection.

Bottom: A fan donated this unusual card catalog, which tracked the transactions of thousands of major league players, to the baseball institute.

“He made it because of his portrayal of Charlie Brown’s deep understanding of baseball,” jokes Price. (For non-Peanuts fans: Charlie managed his neighborhood’s awful team and frequently had his clothes knocked off by line drives.)

The Reliquary also honors notable fans with a Hilda Award, named after Hilda Chester, the Brooklyn Dodgers enthusiast who raised hell in the stands with a cowbell, despite having had at least two heart attacks. One recipient got the 2020 Hilda Award for collecting used game bats from the Red Sox going back to 1960; another snagged a 2003 award for co-writing the fight song “Meet the Mets,” played before the team’s home games and requested at diehard fans’ funerals.

Emma Amaya got a 2013 Hilda for her L.A. Dodgers’ fandom — she dresses up as Hilda Chester at Dodger Stadium and has thrown the first pitch twice. She recalls the awards ceremony well.

“The event starts with the M.C. ringing a big cowbell, followed by many of the attendees ringing their own cowbells and regular bells,” she says. “The playing of the national anthem and ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’ by a group, trio or one person follow. These are exceptional, unique people doing this. There was an 82-yearold lady singing upside down (standing on her head). There was longtime Chicago White Sox organist Nancy Faust.”

Amaya keeps her award, an actual cowbell, in her home on prominent display. “It is like receiving an Oscar,” she says. “I told Terry Cannon that I did not think I deserved such honor. Terry told me, ‘It is not how you feel. It is how others feel about you.’”