BY ETHAN BARON

Two dozen people lie on the floor of San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral gazing into a cone of light shining down from a hundred feet above. They look up into radiance: shifting beams and curtains of blue and green, red, purple, yellow and pink, patterned with swirls and billows from manufactured fog. Deep, slow music evoking monasteries and whale song resounds among the church’s towering concrete pillars.

Experiencing the “Grace Light” art installation could be compared to gazing into the eye of God — or something like it.

“At the end, you almost felt like you were taken into the dome of heaven,” said San Francisco artist Pat Lee, 73, freshly upright after about 15 minutes on the cathedral floor. “I didn’t expect it to be so emotional.”

Appreciation of light unites humanity: sunsets gleaming through clouds, the face of a loved one in a candle’s glow, lasers glittering in a concert hall and the burst of fireworks in the night sky. In recent years, advances in technology and the influence of artists who ignite the night desert at Burning Man have brought artistic illumination into everyday life — sparking not just interest, but engagement and joy.

Grace Light, by Berkeley artist George Zisiadis and San Francisco composer Gabriel Gold, is just one of many light-based installations brightening cities and communities across the Bay Area. There are iconic, illuminated letter and word sculptures at San Jose’s airport and a winery in Santa Rosa. A giant woman made of steel and stars towers in San Leandro. To the south, a new geometric night-time wonderland has expanded Paso Robles’ spectacular Sensorio Field of Lights. And

Lying on the floor, guests are bathed in light while viewing the Grace Light art installation at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral.

JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/STAFF

the biggest light installation of all, the Bay Lights project that lit up the Bay Bridge for 10 years until going dark in March 2023, is set to return in even more magnificence in 2025.

“Every origin story starts with light. It’s sort of at the genesis of every culture. It’s speaking a universal language that touches us at the core,” says Ben Davis, founder of Illuminate, the nonprofit behind Bay Lights, Grace Light and other largescale works that fall into an artistic genre closely linked to the Burning Man festival of art, music and experience held each summer in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

Among the most prominent artists and artworks to emerge from Burning Man are Marin County’s Laura Kimpton and her Monumental Words sculptures, which have traveled from the desert to sites around the world. At San Jose Mineta International Airport, her “XO” helps turn arrivals into celebrations. At Santa Rosa’s Paradise Ridge Winery, her “LOVE” stands tall after barely escaping the devastating Tubbs Fire in 2017.

Kimpton launched the project, a collaboration with artist Jeff Schomberg, at Burning Man in 2010 with “MOM.” The next year came “OINK,” because Kimpton was farming pigs, and humans may need reminding that we’re animals, she says. The sculpture, installed far out near the Burning Man boundary fence, had external lights that flashed on and off.

“You could see OINK from five miles away, and it would go, ‘OINK, OINK, OINK,’” says Kimpton, 60.

Kimpton, of San Anselmo, started putting light inside her sculptures in 2016, when she found spotlights couldn’t prop-

erly illuminate the @ symbol in her “@EARTH#HOME” installation at Burning Man. “It drove me nuts,” she says. “I’m kind of a spastic artist who can kind of be messy and everything, but I’m a trained photographer: I like balance.”

For her “XOXO” the following year, the crew put light-emitting diodes (LEDs) inside the sculpture, “so that Laura doesn’t have a little fit,” she says.

Now, a version of that sculpture welcomes travelers and the friends and loved ones who come to meet them at the San Jose airport’s Terminal B. Twice the height of a person, “XO” represents the hugs and kisses ubiquitous at airports and changes color every few seconds, from red to green to blue and on through the spectrum, light shining through hundreds of bird-shaped cutouts in the sculpture’s aluminum sheeting.

“When you can change the colors of the piece, it makes a party, it makes an event,” Kimpton says.

Light, when built into art, also attracts. “It makes people look,” says Charles Gadeken, whose otherworldly “Entwined” sculpture garden illuminates San Francisco’s United Nations Plaza. “I get tired of seeing people ignore art. They walk past it. They don’t see it at all.”

At the plaza, eight of Gadeken’s chest-high techno-shrubs, plus one a bit taller, sprout from a sand-covered rectangle recalling the Black Rock “playa,” with the seedy chaos of nearby Market Street substituting for the kaleidoscopic madness of Burning Man. Each shrub features dozens of stalks topped with 3½-inch plastic cubes that glow, pulsate and switch colors: pink, chartreuse, orange, blue, white and purple. Every so often, some flash.

“There are ways to use light art that really engage people,” says Gadeken, 60, whose path to artistic prominence also started at Burning Man. “The world could use some light. The cities have many dark places that could be illuminated and made more beautiful and made more fun.”

The Bay Area’s most-viewed work of light art, the Bay Lights that sparkled and shone from cables holding up the western span of the Bay Bridge, blinked to black in 2023, shut down after the lighting systems dete-

Above: Onlookers take in the iconic Bay Lights installation one last time before the lights were extinguished on March 5, 2023. The installation will flicker back to life in even grander form next year.

NHAT V. MEYER/ STAFF ARCHIVES

Laura Kimpton’s XO sculpture greets arrivals with love at Terminal B at the San Jose Mineta International Airport.

NHAT V. MEYER/ STAFF

riorated in the elements and sea air. Illuminate’s Davis is working with local, state and federal authorities to bring it back in 2025 — and make it visible from the East Bay and Peninsula, instead of just San Francisco and Marin County, to deliver what Davis calls “aesthetic equity.”

This project, too, arose from Burning Man, albeit indirectly. In 2010, Davis returned to the Bay after a week’s immersion in the festival’s culture of contribution, amid phantasmagoric structures ablaze with light. He had a hard landing back home in San Francisco. As he looked up at the Bay Bridge from The Embarcadero, inspiration struck: The generosity and beauty of the playa didn’t have to stay there.

“I just wanted to bring it to where we live and make it last longer and reach more people,” says Davis, 63.

Someone sent him a video of an installation by artist Leo Villareal at the San Jose Museum of Art. Davis called Villareal and asked him, “If the Bay Bridge

was your canvas, what would you do?”

Villareal turned the span into a 1.8-mile long harp of light, the blinking white LEDs appearing to flow up and down in glimmering drops, with patterns sweeping sporadically across the lines of steel cables. He and Davis are again collaborating, aiming to set the span alight again in early 2025 with — they hope — an expansion from the original 25,000 lights to 50,000. If Davis can satisfy officials’ concerns around driver distraction, each of 300 cables will have white LEDs on both sides reaching as high as 240 feet above the bridge deck to create “The Bay Lights 360.”

“It won’t really be clear who gets the view and

who doesn’t until we turn it on,” Davis says. “We’re doing our best to keep that view open to the entire Bay Area.”

A new brand of LED should dramatically increase the installation’s lifespan, Davis says.

Over the past decade, low-power, relatively cheap LED light has driven a world-wide expansion of light art, says Nancy Sweeney, an art consultant who curated the collection at The Ameswell hotel in Mountain View, where a mesmerizing work of LEDs, mirrors and fiberglass by artist Chul Hyun Ahn greets guests at reception.

But while art with built-in illumination grows in popularity and visibility, the need for maintenance and the potential for glitches or the deterioration that undid the Bay Lights give pause to many owners and operators of locations that host art, Sweeney says. Still, with advances in technology, “people are more willing to go there,” she says.

Increasingly reliable LEDs, along with evolving systems for controlling how they light up, are also creating a new wave of interest among artists, says Jia-Ming Day, a light artist and professor of New Media Art at Taipei National University of the Arts. He is studying light art in the Bay Area as a visiting scholar at UC Davis and began his U.S. studies at San Jose State University in 1992. Day, 59, believes this region’s residents will be seeing more light-based public art, often installed as a remedy to dark urban spaces.

Public appetite for captivating light art can be measured by the Sensorio “Field of Light” in Paso Robles. After flickering to life in 2019, the 15-acre, ground-level array of 100,000 color-changing spheres by artist Bruce Munro was to last about eight months. But it has drawn so many vis-

Grace Light at Grace Cathedral at 1100 California St. in San Francisco is free (donations encouraged), and takes place on select evenings from January through April and September through November. Tickets are released at noon on the Tuesday before. Find details at http:// gracecathedral.org/grace-light.

itors to wander in awe among the orbs that it’s been expanded and made permanent. Now, a new light-art exhibit has popped up at Sensorio: “Dimensions,” a music-aided ramble among glowing metal geometric sculptures, the work of long-time Burning Man artists Serge Beaulieu and UC Berkeley graduate Yelena Filipchuk.

Back by the Bay, a stone’s throw from the San Leandro BART station, a 55-foot-tall sculpture of a nude woman rises from the city’s Tech Campus. Her toes are pointed, her back is arched, her head is tipped back, and her arms stretch toward the dome of heaven. An intricate labyrinth of steel tubing forms her skeleton. Beneath her steel mesh skin, she is lit from within by 2,500 LED lights that up close appear as pinpoints. From the BART platform, they look like stars, and from further away, they make her glow like a distant galaxy.

Built by Petaluma artist Marco Cochrane, Truth Is Beauty debuted in 2013 at Burning Man. Today, the sculpture brightens the darkness for many a tired commuter. “I like how it lights up,” says Shanea Espinoza, 31, a hostess at a nearby restaurant who takes BART home to Hayward after work. “It just adds a nice sparkle in the night.”

Burning Man light

tunnel sculpture dazzles downtown San Jose

BY CAMERON DURAN

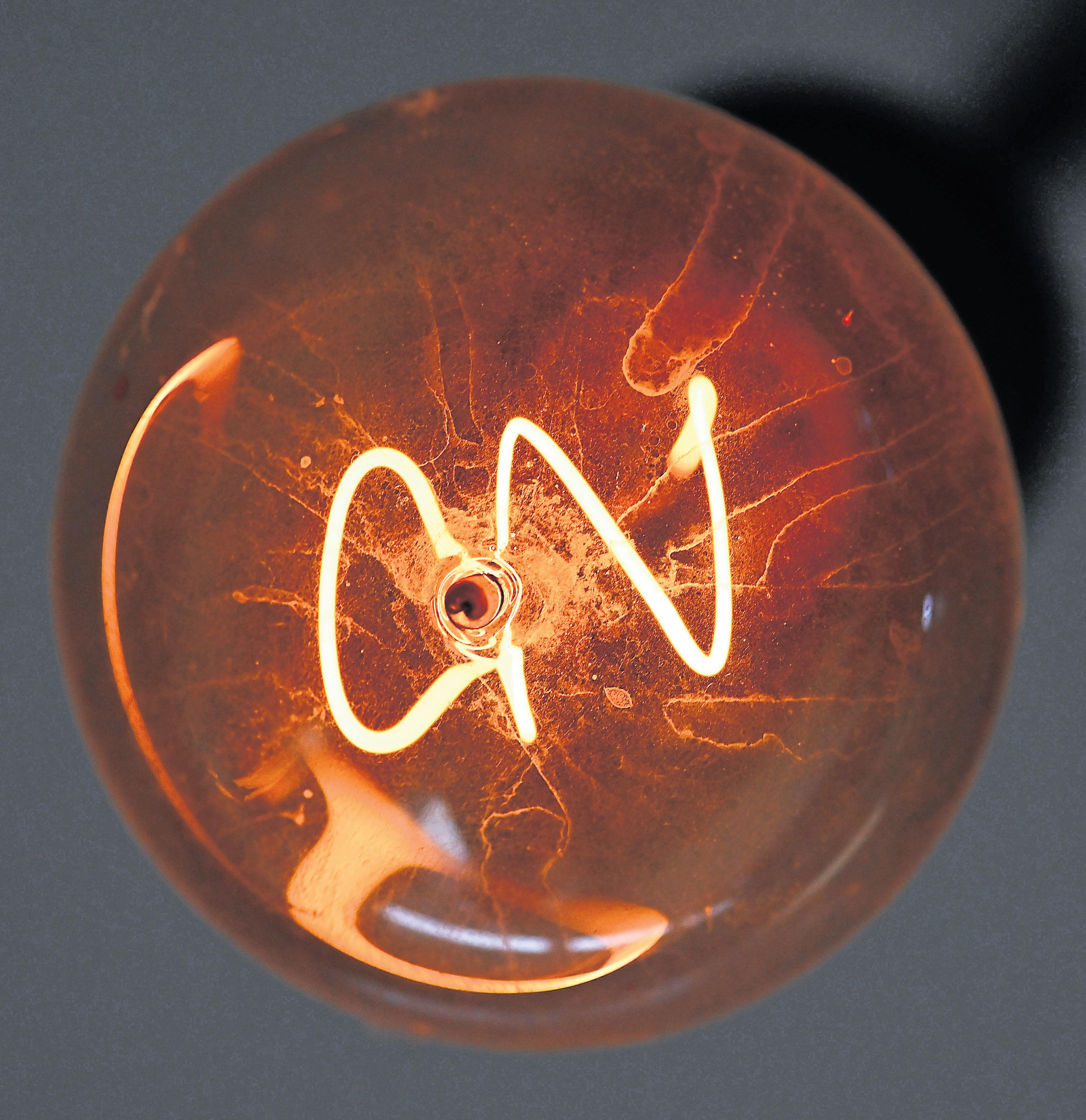

The huge metal rings vertically embedded in the sidewalk just outside San Jose’s City Hall go almost unnoticed in daylight, blending into the building’s sleek architecture. But when the sun sets, the concentric arches come to vivid, pulsing life.

Waves of colorful lights race down the runway’s curves to the beat of ambient electronic music, an immersive spectacle that evokes the installation’s birthplace far from the downtown buzz — at Burning Man, the annual weeklong, counterculture spectacle in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

Designed by a pair of former Pixar colleagues, Rob Jensen and Warren Trezevant, Sonic Runway made its festival debut in 2016 — where first-time attendee Kerry Adams Hapner, San Jose’s director of cultural affairs, was “blown away” by the sculpture. What if, she wondered, all of San Jose could experience the piece, too?

The answer was the Playa to Paseo project, which eventually brought seven Burning Man artworks from the desert to downtown. In 2017, Sonic Runway became the first installation to take up residency in San Jose, spanning more than 400 feet of sidewalk between Third and Fourth Streets and lighting up from sunset to midnight. A playlist of mellow instrumental tracks plays from one end of the tunnel, with each ring lighting up as the beat of the music reaches it.

The light art installation quickly charmed the city and became a go-to downtown photo spot, with more than 4,000 Instagram posts tagged at the site. Families, cosplayers, bikers and dancers have all shared their love for the colorful LED experience online.

“Sonic Runway has been so wildly popular,” Adams Hapner said. “It’s what you hope. You hope that the community loves it and has that sense of joy that you experience when you walk down the runway.”

The runway is audio reactive, with LEDs synced to its electronic music, but for special events, live music can provide sonic inspiration instead. A cellist, a youth choir and an opera singer have all plugged in.

The runway creators first met in the late 1990s while working at Pixar in Emeryville. Jensen had

been a Burner for years. In 2002, he convinced Trezevant to come along, and it was there that they dreamed up the first version of the sculpture — made with pyramids, rather than rings.

The first iteration was “basically just a series of strobe lights that was a sort of nerdy scientific visualization of the speed of sound,” Jensen said. “The whole point of that was to be able to see the beat of the music, and in particular, to be able to see it coming at you before it got there.”

They funded the project themselves and built it with a team of friends, aligning with Burning Man’s collaborative spirit. It debuted at the 2003 event.

Over the next decade, audio processing and LED technology advanced significantly. Trezevant and Jensen set up a crowdfunding campaign to create an updated version of their installation. The 2016 runway used a sequence of steel arches, which allows lights to move in another dimension, around each curve, and creates a “shared space” for viewers, Trezevant said, while still being open to the surrounding world.

“You can easily move in and out of it, and it doesn’t feel claustrophobic,” he said. “I think it has this really elegant feeling to it.”

Built for a short stay at Burning Man, the work wasn’t intended to withstand the wear and tear of urban life. The desert festival is a celebration of the artistic and the ephemeral, after all. So the city of San Jose eventually partnered with Jensen and Trezevant to create a more permanent version designed for downtown. Sonic Runway made its return in 2021 and is set to remain there until at least 2027.

“There’s a certain magic that comes from the temporariness, but it’s fleeting, and very few people actually get to experience it,” Jensen said. “It’s been very rewarding for both of us to know that this piece has had a life beyond that one sort of bizarre environment, and many more people are able to enjoy it on a daily basis.”

Trezevant hopes passersby of all ages will feel a sense of wonder as they interact with the light installation.

“Every time I walk through the runway, and I see other people, they’re always smiling,” Trezevant said. “It just seems like this tunnel of smiles, everyone having a good time.”

Edison’s little bulb changed everything — and humans have never been the same

BY MARTHA ROSS

Think back to the last time your home and neighborhood were plunged into darkness.

That was Breck Parkman’s experience for 10 nights when the 2017 Nuns and Tubbs fires cut power to his Sonoma County home, and he and his teenage son suddenly had to live without a bright and steady source of light.

“We just did candles, and we had an old oil lamp,” says Parkman, a retired archaeologist with the California State Parks.

The experience reminded Parkman of how local Native American tribes and other preindustrial aboriginal groups he’d studied for four decades lived half their lives in darkness.

His friend Gregg Castro, the cultural director for the Peninsula-based Association of Ramaytush Ohlone, noted that California’s original inhabitants followed nature’s “clock.” They rose before dawn, completed daily tasks by dusk and went to bed early — or gathered at night in their roundhouse, sharing ancient stories and daily gossip around a campfire, their community’s only source of light.

“For thousands of years, they did quite well,” Castro says. “They developed a lifestyle that coincided with nature for the most part.”

These days, the only places to get away from city lights are remote Sierra campsites, like this one in the John Muir Wilderness, or near Point Reyes and other DarkSky-designated areas.

GETTY IMAGES

It’s only during a wilderness camping trip or a power outage caused by extreme weather that 21st century Bay Area residents are reminded, too, that this is how humans lived for hundreds of thousands of years — until the arrival of the lightbulb.

It was nearly 150 years ago that Thomas Edison and others commercialized incandescent lightbulbs and made electric power possible in homes, in factories and on city streets. “Put an undeveloped human being into an environment where there is artificial light,” Edison once said, “and he will improve.”

Indeed, the widespread availability of artificial light has changed human life in profound ways. The illumination of homes, workplaces and public spaces at the flip of a switch has influenced how we sleep, work, socialize, move around our communities and interact with nature and the night sky.

“Never before, in our everyday lives, have we been more dependent upon artificial illumination, arguably the greatest symbol of modern progress,” writes Virginia Tech history professor A. Roger Ekirch, in his 2005 book “At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past.”

But there’s been a price to pay for this progress. Scientists have documented how people’s sleep, circadian rhythms and physical and mental health have been affected by hours of exposure to artificial light, according to Stanford-educated materials scientist and author Ainissa Ramirez.

One notable finding by scientists and historians is that people in preindustrial societies in Western Europe, Africa, Asia and South America didn’t sleep straight through the night. Ekirch says the “consolidated”

Extreme weather and wildfire conditions have made PG&E power outages increasingly common across the Bay Area.

eight-hour model of sleep is a vestige of the Industrial Revolution. Preindustrial people instead slept in shifts — retiring soon after sunset, sleeping for about four hours, waking for an hour or two in the middle of the night to ruminate, work or chat with family and neighbors, before going back to sleep until sunrise.

Meanwhile, all the bright, 24/7 lighting that surrounds our communities, along with the thousands of privately owned satellites being launched into space since 2019, has contributed to a permanent glow in the night sky, which some scientists believe is as serious a global environmental threat as climate change, says Aparna Venkatesan, a University of San Francisco cosmologist whose work focuses on cultural astronomy and space policy.

Light pollution has caused “tremendous” ecological damage to plant and animal species, which rely on Earth’s seasons and daily cycles to nourish themselves, migrate, reproduce and protect themselves from predators, she says. And it has erased people’s ability to see stars

in the night sky.

Preindustrial humans could look up and see a dazzling array of stars. Now, scientists say, 80 percent of Americans can’t see the Milky Way. People around the world are losing a vital connection to millennia of their own history and culture, Venkatesan says, which includes celestial influences in mythology and literature and early breakthroughs in navigation and science.

“This relationship with the night sky is timeless,” Venkatesan said. “And that awe — capital A.W.E. — and curiosity is deeply human, so when we lose that, we are losing something precious that makes us human.”

Before the ubiquity of artificial light, people could experience such awe on a nightly basis. In 1863, Henry David Thoreau marveled at the varieties of moonlight while taking a midnight walk, noticing that his eyes adjusted to the darkness, while his hearing, smell and touch took “the lead” in navigating the forest. Lying back in a pasture, he could

gaze up at the canopy of stars — “jewels of the night” — which would “surpass anything which day has to show.”

The night and its mysteries have long evoked terror, too, of course. Every culture conjures stories of ghosts and spirits emerging in the dark. People learned to expect nocturnal attacks by enemies. They fear criminals on dark city streets even now. And in 1840s California, the agony of the Donner party was intensified by the lack of light in snowbound cabins, accounts show. At night in the black forest, a dying Tamsen Donner tried to buoy the spirits of her three freezing, starving daughters by telling them stories about Daniel in the lion’s den.

Control of fire gave humans a means to beat back darkness even a million years ago. For millennia, they used torches to illuminate the darkness and later, rushlights, candles and lamps filled with oil extracted from plants, fish or whales. These early lighting technologies gave people enough light to do chores at night or to host religious ceremonies, while royals and the rich could stay up to enjoy solitary activities or host extravagant parties.

But those flickering flames were both expensive and fire hazards. “Preindustrial families were constrained in their use of candles and lamps by concerns for both safety and frugality,” Ekirch says.

Hearth fires and lamplight provided a primary source of nighttime illumination in many American homes into the 19th century. The long list of daily chores for the girls in San Jose’s Kettman family in the 1860s included churning butter and

putting wicks and oil in the lamps. Boyle Workman, an early Los Angeles city councilman, recounted the large fireplace at the end of the kitchen in his family’s “pioneer” farmhouse. Workers gathered there each night, “their white teeth gleaming in their dark faces as they laughed and chatted.”

Gas lighting allowed cities on both sides of the Atlantic to change their nighttime cultures by glowing up their streets starting in the early 1800s. San Jose’s downtown streets and some homes finally got gas lamps in the 1860s, but these lights required constant tending, and the gas and open flames remained a potential hazard.

As Edison predicted, the invention of the much safer, easy-to-switch-on lightbulb transformed the “undeveloped” human. It transformed everything — and not necessarily for the better.

On this particular autumn day, Parkman is reflecting on how Edison’s invention has affected even his family interactions. Once power was restored to his Sonoma County home after the long outage, he and his son returned to their usual evening activities — doing household chores or working on their laptops in their separate, well-lit parts of the house.

We may think of electric lights as the norm, but that wasn’t true even a few decades ago. As a child in the 1950s, Parkman would visit his grandparents, whose rural home in Georgia didn’t have electric lights. Evenings were spent on the front porch, everyone talking and watching fireflies dance in the nighttime shadows.

“My grandfather would tell

Kris Bel, of Concord, checks his smart phone as smoke lingers above the San Francisco Bay in October 2019, when power outages made the setting sun the only reliable source of light. JOSE

stories, and it was just a different way of being, he remembers. “I think family had a different definition in semi-light than it does in full light.”

Meanwhile, scientists theorize that the constant use of artificial light has set people on a course to develop a range of modern illnesses, as Ramirez said, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity.

Changes to how we sleep — or don’t sleep enough — is one issue, as Ramirez explained in an interview and in her 2020 book, “The Alchemy of Us.” So, too, is the fact that human physiology has become disconnected from Earth’s seasons and its daily cycles. A photoreceptor in the human eye responds to light, whether from the rising sun or from lights in our homes and on our devices. This light tells our brains to release chemicals that wake up the body — the opposite of what happens when the sun goes down, and the brain signals the release of melatonin.

With so much artificial light in our lives, “we are experiencing too much of the wrong kind of light at the wrong part of the day, and these lights affect our health,” Ramirez says. We spend too much time in “daytime mode,” flooding our systems with growth hormones that, studies show, increase the risk of cancer.

Beyond human health, the proliferation of artificial light has disrupted the lives of species around the world, according to Venkatesan. Sea turtles along U.S. beaches are having trouble finding dark beaches where they can nest, because lights blaze from hotels and vacation condos. Meanwhile, birds can’t see the moon or stars well enough to migrate at night, or they become attracted to lights in buildings and crash into them.

Devastation to biodiversity is one impetus for the DarkSky International movement, which advocates for protecting night skies from light pollution. A DarkSky initiative began in West Marin County in 2020, when residents in Point Reyes Station began hearing neighbors complain about lights around town that were keeping people up at night.

DarkSky West Marin joined forces with Point Reyes National Seashore to have a portion of Marin County designated as Northern California’s first DarkSky community, a regional officially recognized for good night sky quality by DarkSky International. DarkSky West Marin regularly invites the public to stargazing events near Tomales Bay — on the first clear night in the week before a new moon — to hear stories about the celestial bodies above and to feel that sense of awe as they gaze at the Milky Way. And, says West Marin co-founder Peggy Day, guests are asked to look south and see “the dome” of light all the way from San Francisco. “We want people to see the effect of human lighting on the sky.”

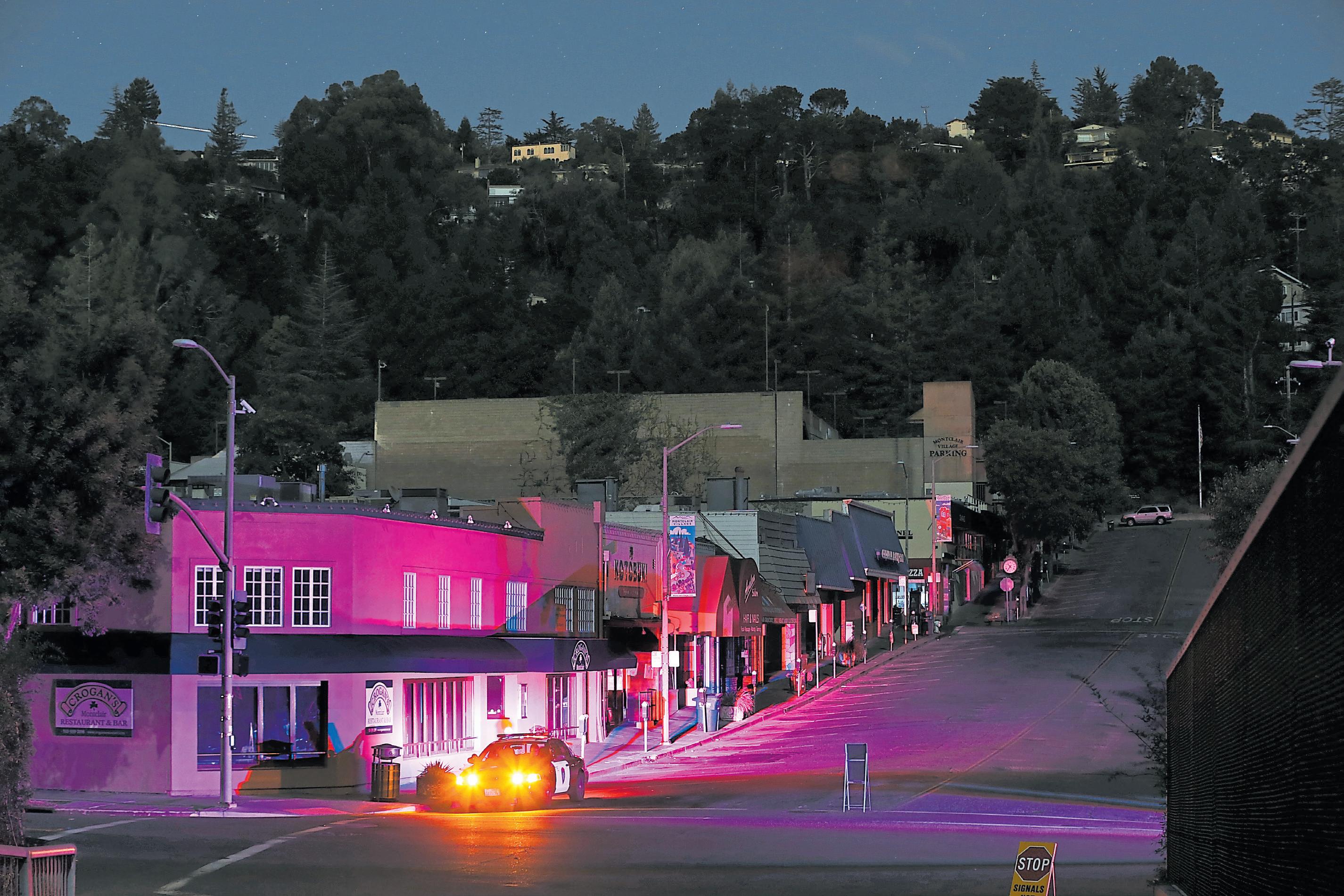

The Tactile Dome exhibit at the Exploratorium in San Francisco immerses guests in complete darkness as they make their way through the exhibit.

ARIC CRABB/STAFF

Let your sense of touch guide you inside

BY BRITTANY DELAY

Light shows, LEDs and screen projections are all the rage these days. Everywhere you go, there seems to be some hoozit or whatzit aglow. It’s often for good reason — these visuals can be stunning — but whatever happened to less is more?

If that sentiment resonates, head for the San Francisco Exploratorium’s Tactile Dome. For more than four decades, this 33-foot-wide geodesic structure has plunged participants into complete darkness, challenging them to navigate a labyrinth of textures solely through touch.

Enter the dome, and you’ll spend the next five to 10 minutes walking, crawling, climbing, bouncing, twisting, turning and sliding your way through a sequence of 13 pitch-black chambers. All the surfaces, walls, floors and ceilings of the chambers are covered in materials that blend, change and contrast, confronting explorers with a most tactile experience. Bounce? Twist? Turn? The dome almost sounds like the

immersive version of a bop-it. It isn’t just child’s play, says Rachel Hyden, the Exploratorium’s senior director of visitor engagement. Visitors of all ages are drawn to the darkness, and what they take away from it is as individual as they are.

“The experience is not particular to children or adults,” Hyden says. “We have adults for whom going through the dome is conquering a fear. For others, you can just hear the laughter and hilarity they’re experiencing as they go through. There’s no universal experience.”

So, whose funny idea was it anyway to have people get on all fours and crawl their way through total darkness? The dome is actually the brainchild of Carl Day and August Coppola. (Yes, that Coppola, brother of filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola and father of actor Nicolas Cage.)

Coppola fostered a keen interest in perception bias. He argued that people rely too heavily on visual information

The Tactile Dome is open from 10:15 a.m. to 4:15 p.m. daily and from 6:15 to 9:15 p.m. for “After Dark” hours on Thursday nights at the Exploratorium on Pier 15. Dome tickets are $16 (reservation only), plus museum admission ($30-$40), and a portion of the exhibit is wheelchair accessible. Find more details on the Tactile Dome, ticket information and admission restrictions at exploratorium.edu.

to understand the world, often overlooking the sense of touch and developing a reluctance to physically engage with others and the environment.

Perhaps Coppola saw, early on, the ways in which modern society was trending towards isolation. However, even he may not have predicted the relevance of the dome in our digital age. In a world increasingly dominated by screens and technological distractions, the dome offers a rare experience, forcing visitors to disconnect from the visual and embrace the tactile.

Of course, a lot of attractions promise “immersive” activities, but the dome is the real immersive deal. When the dome first opened in 1971, a press release from the Exploratorium reported visitors “compared the experience to being born again, turning yourself inside out head first, being swallowed by a whale and inevitably, being enfolded in a giant womb.”

So what exactly lies inside?

“I don’t want to give away all the secrets,” Hyden teases. “One of the things that we really try to maintain is the sense of mystery about the dome. We don’t tell you all the things, because we want it to be something you experience for yourself.”

Expect surprises. Darkness. And then, light.

BY MARTHA ROSS

No one ever really wants to go to the hospital, and hospitals know it.

That’s one reason that a growing number of medical centers have filled their walls, lobbies and waiting areas with art, hoping to make what can be a worrying or painful experience for patients into something more welcoming. Being able to look at a beautiful mural or sit in a garden next to a stunning piece of sculpture is thought to be healing for patients, as they undergo tests, surgery or treatment for serious health conditions.

The art world also has taken notice that hospitals, especially those displaying high-quality works in newer, state-of-the-art buildings, have become art-filled public spaces, just as libraries, parks and shopping centers have done.

Both patients and art lovers can find aesthetic relief in two striking, large-scale illuminated sculptures on display at John Muir’s Walnut Creek Medical Center. The sculptures, by two internationally recognized Tucson-based artists, were commissioned for the hospital’s new Jean and Ken Hofmann Cancer Center, which opened in February in the gleaming, 155,000-square-foot Behring Pavilion.

Both sculptures are equipped with lights that allow them to glow at night, making them

visible at all hours of the day in remarkably changing ways. The illumination means “they can reach out beyond the bounds of the sculpture itself,” says Joe O’Connell, creator of the sculpture, “Uplifting Together.” He and Barbara Grygutis, who created the second sculpture, “Regeneration,” specialize in art that uses light. For this installation, their pieces embody themes from nature that are meant to inspire hope and healing.

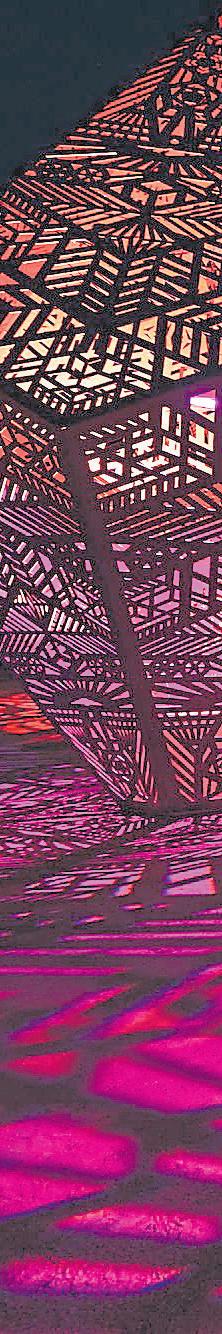

Visitors arriving at the pavilion’s main entrance from the parking lot will encounter Grygutis’ “Regeneration” first. Standing 20 feet tall, the sculpture consists of two, curved, elongated pieces — halves of a whole — standing on end. Their aluminum panels feature an intricate, lacy network of cutouts, through which daylight and other light sources can shine.

Grygutis, whose sculptures also grace public spaces in Santa

Clara and Palo Alto, said she envisioned a seed pod, bursting open to start a cycle of new growth and life. The nature theme is especially apparent after dark, when the green lights embedded within make the sculpture glow in hues reminiscent of leaves or blades of grass, radiating out into the night sky through the lacy panels.

“Hopefully, people find it beautiful and calming,” Grygutis says. “Hospitals more and more are commissioning art as a point of interest and to create a calming environment.”

On the other side of the pavilion, visitors will find O’Connell’s “Uplifting Together,” a 19-foottall installation mounted against the pavilion’s outdoor facade. Tucked away at the far end of the center’s meditation garden, it’s shielded from traffic noise — and both the garden and art can be seen by patients visiting the center’s first-floor radiation and oncology department.

Like Grygutis, O’Connell used aluminum to create forms that seem alive with movement and growth. He shaped the metal into a vinelike “twining branch,” he says, with tendrils and softly colored orbs that rise across the wall and reach up towards sun and sky. LED lights follow the course of the tendrils and are programmed to switch on when the sun goes down, creating a gentle nighttime glow that rises

up out of the garden.

O’Connell saw the “twining branch” as connected to life “in all its various forms.” It might remind some people of the human circulatory or nervous systems, he says, but you see those forms in nature as well.

O’Connell says his love of tinkering and illumination comes from growing up in New Jersey — his father was a math teacher, his mother an artist — near the West Caldwell laboratory of Thomas Edison, who helped invent and commercialize the incandescent light bulb. O’Connell says his grandfather and Edison were friends.

When O’Connell was commissioned to create the sculpture for John Muir hospital, he said his work was informed by his father and his health problems, with his father going “from one hospital to another” and spending time in a recovery facility before he could return home.

“It gave me a chance to think about what type of art people need in hospitals,” he says, especially when “they are spending long periods of time in one place or returning again and again.”

The experience also made him appreciate the unique challenges and rewards of creating art for a healthcare setting, knowing that people will come to his work with the widest range of emotions and reasons they might be there.

BY JOHN METCALFE

Ever since she can remember, Desiree Heveroh wanted to be a lighthouse keeper on the East Brother Light Station, a three quarter-acre speck of an island in the San Francisco Bay. After applying three times, the Richmond resident finally got her wish in 2020, when Covid shut down the island’s public bed-and-breakfast, and she was called in for maintenance and warding off marine squatters.

Heveroh took a boat out to meet her fellow keeper, a sea captain, and settled into a small Victorian abode with unbeatable 360-degree views. That’s when the power went out.

“The submarine cable failed, and we were literally stranded on the island. There was a boat on a hoist,

but that only works when you have power,” she recalls. The sea captain eventually had to leave for work elsewhere. “He strapped his dog to his chest, pushed a kayak off the island and paddled himself to the mainland. And then it was just me.”

For the next two months, Heveroh lived her own version of Tom Hanks’ “Cast Away” — although replace Wilson the Volleyball with a helpful raven she named Edgar Allen. She couldn’t shower more than once a week, due to no water pressure, and she canned her own food because freezers weren’t operational. It was rough living like it was the 1800s, but she made the best of it.

“I grew a garden. I trained a raven. I had a baby duckling. I learned a language. All the things you say you’re going to do, I did,” Heveroh says. “I didn’t look at clocks or calendars,

and it was as glorious as it sounds.”

It takes many — sometimes odd — factors to become a lighthouse keeper. First, you need a lighthouse. In the Bay there are plenty. The surge of marine traffic following the 1850s Gold Rush saw them built everywhere, from deadly open-ocean waters to rocky coastal cliffs and inside the sheltered Bay, where several lighthouses continue to aid navigators.

East Brother Light Station was built in 1874, after crews blasted the top off an island north of what’s now the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge. It was the home of many lighthouse keepers and their families, who averted ship collisions and groundings with a foghorn and a beaming, beehive-shaped Fresnel lens. The U.S. Coast Guard automated the station in 1969, and in 1980 — thanks to heroic efforts from pres-

ervationists — it reopened as a charming inn where anybody can stay for a one-of-a-kind vacation. (You just can’t shower, if you’re only staying a night.)

The inn has five rooms with old-timey beds, nautical art and a grand dining table where guests eat gourmet meals cooked by the innkeepers, who generally serve in pairs for two-year shifts. Guests swap world-traveling tales in the parlor before bedtime, and the next morning, ring the station’s 1930s diaphone foghorn, which shakes the entire island with a sound between a roar and a surprised grunt. Then they return to the mainland, leaving behind what are jokingly referred to as the island’s “cellmates” — the lightkeepers.

Hundreds of keepers have served at dozens of Northern California lighthouses, all built for a variety of reasons but mainly because something awful happened there. Mile Rocks Lighthouse, southwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, was erected in 1906 after a passenger steamship, the City of Rio de Janeiro, struck a submerged reef. Roughly 130 people drowned, and bodies (including that of the captain, identified by a watch chain around his rib cage) washed up near Fort Point for years.

Point Bonita Lighthouse in the Marin Headlands went up in 1855 on a small promontory that’s claimed at least 10 wrecks — that’s among more than 300 vessels that wrecked or ran aground near the Golden Gate during the Gold Rush — including the S.S. Tennessee, whose skeletal remnants can still be seen at low tide. Pigeon Point

Lighthouse near Pescadero owes its name to the clipper Carrier Pigeon, which tore apart on the ocean’s rocky bottom in 1853. The ship that came out to save her also ran aground.

In 1898, San Francisco became the first city in America to deploy a lightship, a vessel that stayed anchored in place outside the Golden Gate and acted as a floating lighthouse. Lightships were used in California into the 1970s, sometimes with “submarine bells” dangling 30 feet below, ringing constantly and annoying

Built in 1855, the Point Bonita Lighthouse was the third lighthouse constructed on the West Coast.

JANE TYSKA/ STAFF ARCHIVES

the fish, on the theory that distant ships could sense and navigate from the sound. Lightships were constantly getting rammed by other boats, though, and the U.S. Coast Guard eventually replaced them with humongous automated buoys.

East Brother wasn’t built so much to warn of dangers in the water, but for navigation for local shipyards and up and down the Sacramento River.

“Back then, they didn’t have radios, radars, any of that stuff,” says Tom Butt, the former mayor

of Richmond who helped restore the light station into an inn.

“When ships were moving at night, the only thing they had to go by was lighthouses. They could identify each lighthouse because the rotation of the lights were all distinctive and could plot their course by going from lighthouse to lighthouse.”

Early lightkeepers were known as “wickies” due to all the work they did on the lard oil-powered (later kerosene) lamps. They refilled the oil canisters, trimmed the wicks

to keep smoke from darkening the lenses and wiped sea scum from the lighthouse windows. They painted and repainted everything, cleaned mountains of guano from the buildings and kicked dead fish that washed up back into the ocean.

At some lighthouses in deeper seas, the keepers tied ropes around themselves to keep from being swept into the abyss. (Up in Humboldt County, there has been evidence of a 150-foot-tall rogue wave striking a lighthouse.) In the open Pacific, there

are no such protections — one man trying to reach his lighthouse by boat was battered so badly by waves, he simply died a few days later.

And keepers dealt with a constant ringing in the ears, thanks to the foghorns. Dennis Powers writes in his 2007 book, “Sentinel of the Seas,” which chronicles life on the St. George Reef Light near the California/ Oregon border:

“As these horns blasted, keepers over time could permanently lose part or most of their hearing ... Wickies changed their way of talking when the horn sounded and would only talk during the intervals of silence. After the foghorn stopped, the keepers and their families often found themselves still talking in that same strange staccato language.”

Given the isolation, lightkeepers could grow into the

The lighthouse at Pescadero’s Pigeon Point Light Station, a state historic park, was named for a clipper ship, the Carrier Pigeon.

JANE TYSKA/STAFF ARCHIVES

best of buds or become mortal enemies. One keeper in Oregon tried to murder his “cellmate” by putting ground glass in his food. Another pair arguing over a wife got into a physical fight, the fatal lesson being never take a hammer to a knife fight. Food was a source of friction. In Alaska, three keepers fell out over whether they liked potatoes mashed or fried, and for the next six months, never spoke a word to each other.

In 1937, the keepers of the St. George Reef Light were trapped by a large storm for nearly two months with no new food, no mail and dwindling supplies of coffee and tobacco.

“The four men under (keeper Georges) Roux stopped speaking to one another for one month, and to say ‘good morning’ became a personal affront,” writes Powers. “The irritating tone of men’s voices added to

the screeching winds, moaning diaphone foghorns and the tower’s shuddering. Individuals ate facing away from one another, avoided the table all together or ate by themselves. Fist fights broke out, and men threatened one another; it was a miracle that no one was murdered or severely injured.”

Times of tragedy may have provided moments of bonding. A lighthouse, it turns out, is an excellent perch to watch natural disasters unfold. The crew of St. George witnessed a tsunami in 1964 strike Crescent City at midnight, killing 11 and destroying 30 city blocks. In 1906, the keepers of East Brother watched San Francisco burn after the Great Earthquake, no doubt wondering about friends and innocent others.

Many of the first keepers at East Brother hailed from European countries, including Denmark, Ireland and England. They had to read, write and be up for an immense amount of scut work. Keepers hauled coal deliveries, sometimes 40 tons at a time, up from the wharf to power the boilers. They were in charge of the foghorns, but because those take time to charge, they first rang a bell — once every 15 seconds for 45 minutes. (Nearby at Point Knox on Angel Island, one female keeper received a special commendation for banging a bell in heavy fog for an incredible 20 hours and 30 minutes. She eventually retired due to “broken health” from long and solitary fog watches.)

All that might be enough to drive a body to drinking, and there is indeed evidence

it happened. “January 2 1883: Wind S., light, hazy. (Assistant keeper) Mr. Page took the mail over to San Quentin, returned drunk,” one East Brother superintendent noted in his log. “January 11 1883: Wind N.E., cold, light, foggy. Mr. Page went for the mail, returned at 2:30 p.m. drunk, mail wet.”

There was no doctor on the island, which made pregnancies difficult. When his wife went into labor, John Stenmark, a turn-of-thecentury keeper who stayed there 20 years, rowed 2.5 miles to fetch the closest medic at Point San Quentin. When she had a second child, he did the same thing again — regardless of potentially perilous storm conditions.

All the potable water on the island comes from rain that gets funneled into an immense cistern and a redwood tank. Back in the day, there were concerns about lead-paint contamination — authorities told keepers to mix in powdered chalk and forget about it.

“Seagulls were always a problem,” one former resident recalled in Frank Perry’s 1984 book, “East Brother: History of an Island Light Station.” “All summer, they would fly over, eat, scream and defecate ... It was rain water, and if you found a crawly thing in your glass, you just didn’t drink all the way to the bottom.”

“There was a frog in the cistern, should have brought him out,” that same person noted. “He was an albino, snow white frog in the cistern

The spark plug-style Mile Rocks lighthouse rises from a windswept rock about a mile from the Golden Gate Bridge, with views that include the Farallon Islands in the distance.

GETTY IMAGES/ ISTOCKPHOTO

with no eyes. He lived there for at least five years, used to keep tabs on him. Not Calaveras caliber but a good-sized frog.”

It wasn’t all grim stuff like the loneliest frog ever. Keepers entertained company from the mainland with music and dancing. There was excellent fishing for delectable rock cod and striped bass, and to stave off boredom, a traveling library sometimes docked with novels and history books. Children enjoyed playing in the boiler room, which was warmer than the rest of the island and had fun Steampunk emanations and oil smells.

The Coast Guard automated the station in the late ’60s, the death knell for the last of the old-style keepers. Community members didn’t want to let it sink into disuse, so in 1979, they formed the nonprofit East Brother Light Station Inc. and did a complete retrofit of the Victorian property. They reconstructed paint schemes with chemical analysis, rebuilt the white-picket fence and stripped asbestos shingles to reveal original redwood siding.

Lighthouses becoming guesthouses isn’t a rare thing. There are at least 14 states that offer the chance to stay in lighthouses. In California, that includes Pigeon Point Lighthouse, Point Cabrillo Lighthouse, the restored 112-year-old Carquinez Strait Lighthouse in Vallejo and Point Arena Lighthouse, with its pet-friendly rooms with queen beds and fully stocked kitchens.

Today’s keepers have a different skill set. They know how to give tours, make beds and cook classy dishes like kataifi-wrapped goat cheese with organic mixed greens and vineyard chicken with truffle-mashed potatoes. Since East Brother reopened as a bed-and-breakfast, there have been approximately 20 pairs of keepers — serving more than 50,000 overnight guests — with backgrounds as diverse as retired Navy SEAL, wooden-boat builder, journalist, scientist, commercial fisherman and flight attendant. To recruit innkeepers, the nonprofit typically posts a listing on job boards like Craigslist that reads: “Keepers must have culinary experience or abilities, must be warm and presentable to the public, and must be enthusiastic and self-motivated. Children are incompatible with this job, as are pets.” It cites these benefits: “Incomparable views; meet a lot of interesting people; one of California’s bestknown bed and breakfast inns; hard work but pretty good pay for a young couple (or couple of any age) doing something unique; birds, marine mammals, fresh air, boats; and history.”

Desiree Heveroh’s journey to becoming a keeper began with a fascination with the remote East Brother. “From the first time I saw that island, I just felt an indescribable pull, like a magnet,” she says. “I kind of have always known I was going to live there.”

Heveroh’s stories from her year-plus there might sound a little ... spooky. “It was foggy a lot, and everything had a slight dampness to it in the morning. Everything had little green algae growing on it, unless you wiped it off.”

For a place so steeped in history, you might expect

ghosts. Heveroh didn’t have any encounters with spectral sea captains walking out of the mirror and demanding to know the current price of whale oil, but she did have a dizzy moment making up a shared closet. “I heard ‘This was my closet’ in my head when I was standing in there. So I feel maybe I was reincarnated from one of the keepers’ kids or something.”

The nature-watching on the island is fantastic. “When seal mothers were giving birth to pups, they’d do it on my island,” she says. “Osprey and ducklings and other birds — I learned all of them and their sounds. I saw a juvenile humpback whale moving across the Bay, blowing out of its blowhole.”

One day, she heard a noise and found an inquisitive raven. She trained it to come close using peanuts. He eventually brought over a bride she named Brandy Alexander. When the power went out for two months, and she could see her frigid breath in her cabin, the ravens started leaving her piles of twigs for the fireplace. “They weren’t from my island, but they’d fly them over from somewhere.”

Heveroh was worried Covid would shut the light station down permanently. But restrictions started easing in late 2021, and she left the island content things would be copacetic.

“I’m not sad I’m not living there anymore. When you really love a thing, you want what’s best for it,” Heveroh says. “She is meant to be marveled at, meant for people to be out there and pouring their love into her energy field — getting engaged, falling in love, conceiving children. She needs and deserves all that, and I’m so happy she has it again.”

BY KATE BRADSHAW

Hidden in plain sight along the Peninsula’s popular “Stanford Dish” hiking trail is a geometrically funky tower, where scientists have been quietly collecting solar measurements for nearly 50 years.

Built in 1975, the Wilcox Solar Observatory was part of a Navy project to study the sun’s magnetic field. The sun’s corona spews out a constant stream of charged particles, a solar wind that reaches speeds of up to a million miles an hour as it spreads those particles across our solar system.

Why was the Navy interested in something so solar-related? When the direction of the magnetic field within that solar wind changes, it can reduce the Navy’s ability to communicate with submarines, says Stanford physics professor J. Todd Hoeksema, who leads the university’s Solar Observatories Group, which includes the Wilcox observatory.

For the last four decades, the solar observatory has collected low-resolution maps of the sun’s magnetic field each day, weather permitting. Rain and cloud cover can make those efforts challenging, of course. But on sunny days, a resident scientist — typically, a Stanford physics graduate student — collects solar data, taking measurements for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, three or four times a day to map the field.

It’s a gig that comes with onsite lab housing, a quiet retreat from bustling campus life that’s considered a perk, although Hoeksema recalls being startled by a tarantula on his first night there as a grad student long ago. Around 30 students have lived at the observatory over the years. (Or rather, 31 — one scien-

tist had a baby during her residency.) Many of those scientists, Hoeksema says, have gone on to careers as solar astrophysicists.

At the moment, physics grad student and resident scientist Sadaf Kadir lives at the observatory with her cat. Several times a day, Kadir climbs the tower to set up instruments, so the sun’s rays hit the lab’s mirrors at the right angle to create a spectrograph capturing details about the solar magnetic field.

The results of her measurements are then reported out at http://wso.stanford.edu, where helioscientists can pore over the data. Laymen can, too, although it makes for a pretty abstruse read.

The non-solar astrophysicists among us can click through to the Stanford Solar Center, a nonscientist-friendly education link that includes everything from vital solar statistics and physics explainers to instructions for baking scientifically accurate planet cakes, mantle, core and all. There’s a recipe for solar cupcakes, too, that includes an advisory that despite the sunny yellow crayons we wielded as kids, the sun is actually white.

“Choose your (frosting) color accordingly,” the recipe says.

From the ground, the Wilcox Solar Observatory tower looks rather like the love child of a pyramid and an observatory. It may not be as flashy or prominent as its famous hilltop neighbor, the Dish, but the solar lab has its own historic legacy. After nearly half a century of observations, the lab has collected a consistent body of data scientists use to track the sun’s 11-year solar cycle patterns, Hoeksema says, and to learn about space weather and solar wind.

In recent years, heliophysicists have put devices into space

“People assume they know a lot about the sun. But there are a lot of open questions.”

Resident scientist Sadaf Kadir

to collect more sophisticated measurements, but the Wilcox observatory provides consistency, a long-term solar record that uses the same method as it did half a century ago. Plus, Hoeksema says, it’s more sensitive to weak magnetic fields than other observatories.

Why is all this — this observatory and these measurements — important?

“People assume they know a lot about the sun,” Kadir says. “But there are a lot of open questions.”

Solar activity shapes what’s known as space weather, and that, in turn, can impact communications and GPS systems — technology used by our smartphones and our cars, not just Navy submarines.

And for observers of night sky phenomena, space weather explains why the aurora borealis was visible in the Bay Area and beyond in May, sending otherworld waves of fuchsia and pale green light across the sky in some places. There was a major geomagnetic storm on the sun.

BY LINDA ZAVORAL AND SAL PIZARRO

It was a brilliant idea, literally and figuratively. Awestruck residents admired it. Scientists praised it. Newspapers and magazines glorified it.

The tower would come to symbolize the city.

Paris and the Eiffel?

No, this was San Jose and its Electric Light Tower, a scientific marvel built several years earlier that put the Bay Area city on the international map, proving that innovation in this part of the world didn’t start with Silicon Valley’s chipmakers.

The 237-foot-tall landmark constructed in 1881 was the brainchild of San Jose Mercury publisher J.J. Owen, who was inspired by San Francisco’s municipal lighting. His project,

however, would be a “moonlight tower,” one structure that would illuminate all of downtown.

And it did — for 34 years.

According to a Sacramento Daily Union article, Owen estimated it would take three such towers to light the whole of San Jose, then just a fraction of its current 180 square miles. “Mr. Owen deserves great credit for the sagacity and energy he has displayed in this undertaking, and San Jose ought to be proud of him,” the paper said.

Not all were as impressed. Farmers from as far away as Los Gatos and Morgan Hill claimed the light emanating from Market and Santa Clara streets kept their chickens awake at night, adversely affecting the egg output.

In 1915, a storm toppled the structure, just as a civic effort to restore the by-then dilapidated tower was getting underway.

But the achievement still stands tall, thanks to History San Jose, the keeper of the city’s cultural heritage and history. A half-size replica of the tower, donated by the San Jose Real Estate Board, was erected in 1977 at History Park. Visitors can see the symbolic icon illuminated during special nighttime events and this upcoming holiday season.

In the century-plus since its collapse, history buffs have wondered whether San Jose’s monument to progress could have been the inspiration for Paris’ famous tower, which was built eight years later, in 1889.

Filmmaker Thomas Wohlmut

Above: San Jose’s 237-foot Electric Light Tower was built in 1881. It collapsed in 1915 during a windstorm.

COURTESY OF THE SARATOGA HISTORICAL FOUNDATION

Left: A replica of the tower at San Jose’s History Park is illuminated each year during the winter holidays.

PATRICK TEHAN/ STAFF ARCHIVES

sought to explore that notion, researching for years and making fact-finding trips to France.

His 2019 documentary, “The Light Between Two Towers,” debunked the rumor of a Gustave Eiffel visit to San Jose, but the film makes a convincing case that the French engineers who designed the Paris landmark would have been very aware of the San Jose Light Tower.

At the time, the tower was celebrated as an engineering and electrical achievement in Scientific American as well as newspapers around the country and the world.

“From the engineers that I spoke with in Europe, they clearly say that engineers start with something someone else has made and try to make it better,” he said in a 2019 inter-

view. “So it’s entirely logical that they would start with our tower — not use it, not copy it — but begin the design process with something that works and was world famous.”

In recent years, civic leaders in San Jose seriously considered erecting another light tower downtown to give Silicon Valley a new landmark. But the group that formed to explore the idea, the San Jose Light Tower Corp., found that a light tower doesn’t carry as much cachet with potential investors and the public these days as a more modern statement piece.

So an artistic competition was held, with scores of designs in the running. The favored installation, “Breeze of Innovation,” will be filled with motion. Though development is stalled, the artwork, with 500 swaying rods, has one thing in common with San Jose’s famous tower: It’s designed to generate electricity.

Details: San Jose’s History Park, 635 Phelan Ave., will illuminate the light tower during this year’s holiday drivethrough, which runs from Nov. 21 to Jan. 1. Find ticket information on the holiday events at www.christmasinthepark.com. Learn more about History Park at https:// historysanjose.org.

Early film history still unspools in the Niles theater that gave Charlie Chaplin work

BY JOHN METCALFE

There is perhaps only one place in America that shows weekly silent movies on antique projectors using the original film prints, the light flickering across the screen as stories unfold. And that is the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum in the Fremont community of Niles, a historic Hollywood-type enclave where Charlie Chaplin made his early movies.

The museum is located inside a 1913 movie theater that’s been restored to its original glory, give or take some exposed lath and plaster. On a recent afternoon, a tour guide leads a group up to a projection room overlooking rows of wooden seats and an upright piano that’s played during screenings.

He raps on the roof of the booth, which is paneled in tin, in case the celluloid accidentally ignited and caused a fireball.

“I like doing that — it lets me know the ceiling won’t fall in,” he says. “If you look on the wall, there’s some charcoal writing from the old manager that says ‘Spit In Box.’ A hundred years ago, you couldn’t smoke up here, but you could have chewing tobacco, and the manager didn’t want to scrape sticky brown spots off the floor.”

The museum has an archive containing roughly 14,000 old

film prints, some from the Em Gee Film Library in Los Angeles, others donated by the film preservationist David Shepard and more acquired through sometimes strange means. (Valuable footage of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition’s opening ceremonies, for example, was found underneath a house in Los Altos.) There is an equipment repair-and-restoration room, a film-research library, a darkroom and hulking projectors, like a 1912 Motiograph made by Chicago’s Enterprise Optical Manufacturing Co. “Those seats right there are

Above: Artifacts from the heyday of the silent film era are displayed at the Niles Essanay museum in Fremont.

Opposite: Actor Charlie Chaplin, seen here in 1922, made 14 films for Essanay.

SHAE HAMMOND/ STAFF; ASSOCIATED PRESS

original to the 1913 theater,” says the docent, indicating a row of four chairs holding a bowler hat and bamboo cane. “We put stuff on there, so people don’t sit on them.”

The museum’s name derives from the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, a Chicago-based operation run by Gilbert Anderson and George Spoor. Anderson’s obsession with Westerns led him to Niles, where its hot, dusty weather and brown hills recalled an Old West town. In 1912, the company began building studios, actors’ cottages and prop workshops

and went on to make more than 350 silent films there. (The Niles studio shut down in 1916 and was razed by the 1930s.)

Many of the movies chronicled the exploits of Broncho Billy, played by Anderson, who was said to be the first Western movie star. A lot of the films were shorts, such as 1915’s “Versus Sledge Hammers,” which has an IMDB summary that deserves mentioning: “The Count received word through a matrimonial agency that Sophie Clutts will inherit a million dollars and goes to her father’s hotel to win her hand. Mustang

Above: The silent film museum’s annual Charlie Chaplin Days inspire Keystone Cops-style hijinks and Charlie Chaplin look-alike contests.

LANE HARTWELL/STAFF ARCHIVES

Left: This Bell & Howell 2709 camera at the Niles Essanay museum in Fremont was used to film scenes for “Sesame Street,” as well as 1920s comedies.

SHAE HAMMOND/STAFF

Pete, however, is in love with Sophie, and when he discovers the Count is making love to her, proceeds to insult him. The Count challenges Mustang to a duel. Being a blacksmith, he chooses sledge hammers as weapons.”

In 1914, the studio lured an early-career Charlie Chaplin in with a then-unheard-of signing bonus of $10,000. Chaplin made 14 films for Essanay, five of them in Niles, including one of his most famous productions, “The Tramp.” Chaplin traveled with his own special crew of cameramen, actors and even a producer — but despite all this highfalutin’ staff, still managed to create moments that were rather Chaplinesque in their ridiculousness.

“They were on location in Oakland for their first film, ‘A Night Out,’ and a crowd had gathered around the Hotel Oakland while they were filming,” says Niles Essanay museum president David Kiehn. “A policeman saw the crowd on the street, and it looked like Charlie was kind of wrestling with (co-star) Ben Turpin during the scenes. This policeman was trying to disperse the crowd and arrest Chaplin — then saw the film camera, stopped in his tracks and let the filming continue from there.”

Chaplin eventually left to work for a different company in L.A., but his memory is honored every summer in the museum-sponsored Charlie Chaplin Day festival. “We bring in guests and Chaplin experts and have costumes we sell at our store,” says Kiehn. “The Chaplin lookalike contest — we have a guy from Canada — is very popular and draws crowds.”

Also in the museum’s vaults are snapshots from the earliest days of film, such as a Miles Brothers short called “A Trip Down Market Street” shot from a cable car four days before the Great 1906 Earthquake destroyed the city. Kiehn identified the film’s portentous date himself by studying license plates and contemporary weather reports, some nice detective work that landed him on “60 Minutes” with Morley Safer. (The short is now in the Library of Congress’ national registry of historically significant films.)

Other short footage includes a gravity car chugging on Mount

Museum president David Kiehn presides over the film artifacts, including this historic Bell & Howell 2709 camera, that comprise the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum collection.

SHAE HAMMOND/STAFF

SHAE HAMMOND/STAFF

Tamalpais, a 1905 Colma boxing match between Jimmy Britt and “Battling” Nelson and the aviator Lincoln Beachey racing an airplane around a horse track.

“Beachey was killed during the Panama–Pacific Exposition,” notes Kiehn, “when his plane plunged into the San Francisco Bay, and he drowned.”

Every weekend, the museum invites the public into its 100seat 1913 nickelodeon theater for a screening of one of its prized films, typically with live piano accompaniment. It might be an Essanay production or Alfred Hitchcock’s 1927 serial-killer movie “The Lodger” or a 1916 cartoon of Krazy and Ignatz, sort of the Itchy and Scratchy of their day. It doesn’t seem to matter the pick — the crowds are always there and always enthusiastic.

“Our first question that we ask the audience is, ‘Who has come the farthest?’ In any given show, there might be people from other states or countries — people have come from Asia, South America, Canada and Europe,” says Kiehn.

“We’re showing films in a silent theater that were shown 100 or more years ago in a town that made silent films and where Charlie Chaplin made films — that’s a pretty unique situation.”

Details: The Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum is open from noon to 4 p.m. on weekends at 37417 Niles Blvd. in Fremont; free admission. Films ($8-$10) are screened on Saturday nights in the Edison Theater, with a Laurel and Hardy talkie matinee one Sunday each month. Find the schedule and more details at nilesfilmmuseum.org.

Livermore’s amazing little electric sphere shines on with nary a flicker

BY KYLE MARTIN

And lo, Livermore said, “Let there be light!”

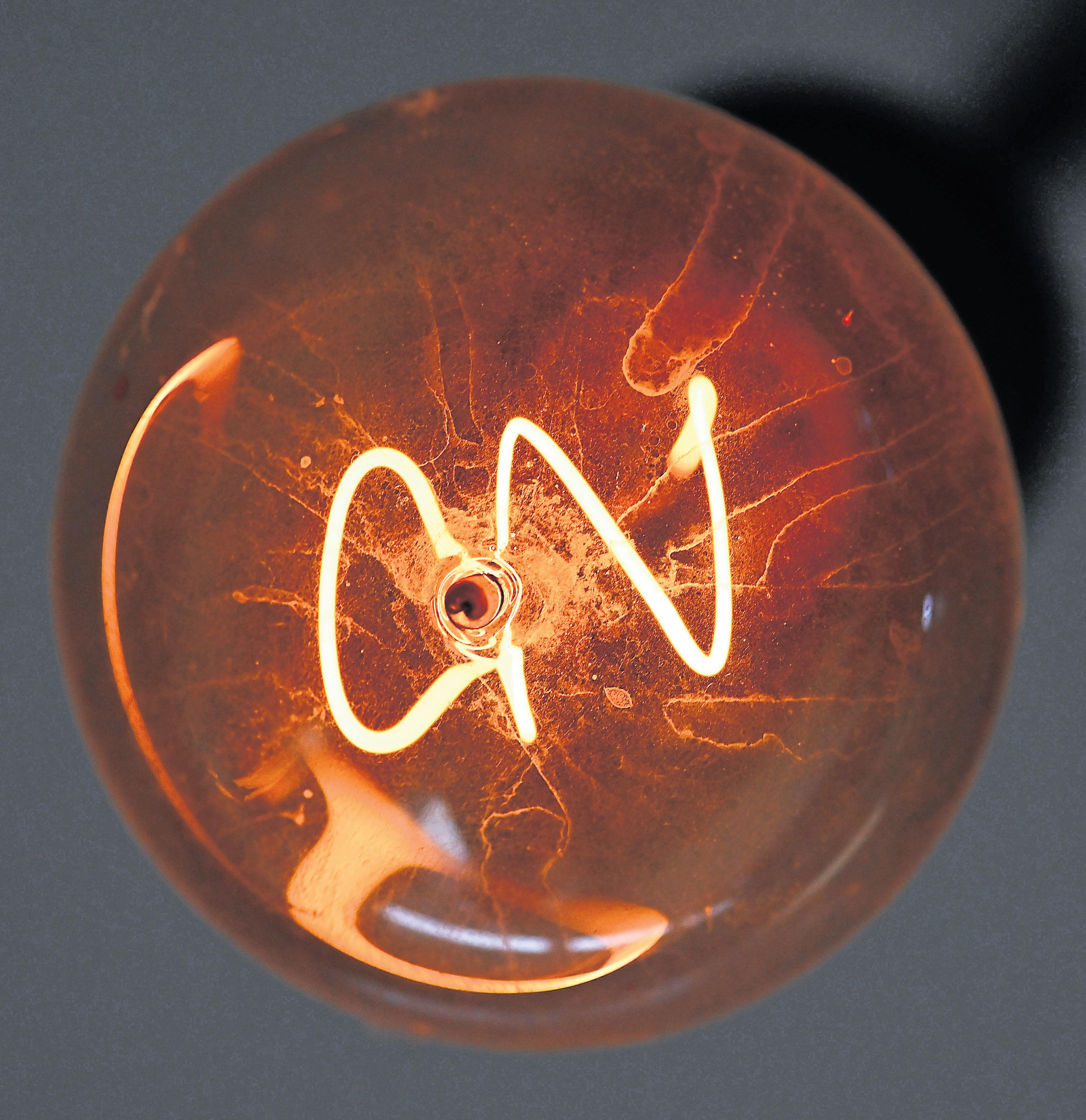

This year marks 123 years of illumination from the Livermore Centennial Light Bulb, which has been a glimmering beacon for the city’s residents since the year 1901.

To put that in perspective, that light bulb is older than the teddy bear (invented in 1902), the Wright brothers’ first flight (1903), the invention of corn flakes (1906) and the first candy apple (1908). The bulb’s light has outlasted most summer flings, many college relationships and the number of A’s seasons at the Coliseum. And the Centennial Light Bulb has been highlighted over the years by the Guinness Book of World Records, which declared it the longest burning bulb on Earth, and the Discovery Channel’s Mythbusters.

“It really is one of the wonders of the world,” says Livermore mayor John Marchand. “People have come from all over the world to see the lightbulb. I think the integrity of that lightbulb matches that of the people it serves. And it shows things can be built to last.”

Consider how long your lightbulbs last before you scoff over such high praise. This bulb is extraordinary. The city celebrated the mighty Centennial Bulb’s millionth hour of illumination in 2015 and has added another 78,849 hours to the total so far.

The bulb’s 60-watt, carbon-filamented birth can be traced back to the late 1890s, when Ohio’s former Shelby Electric Company sent it to Dennis Bernal, who owned the Livermore Power and Light Company at the time.

These days, you’ll find it at the Livermore Fire Department, which opened its first firehouse in 1876. Back then, Livermore was a travel stop on the road between San Francisco and Stockton with a population of 830. Retired deputy fire chief Tom Bramell — official Keeper of the Bulb — says Bernal donated the bulb to the fire department in 1901 to illuminate a hose cart house, where firefighters once hitched their horses to a trolley before riding out to battle fires.

At the time, firefighters used a kerosene lamp for illumination in the dead of night. Bernal hoped his electric bulb would add a glow — safely — so firefighters could see in the dark without risk of burning down their own cart house.

The light has beamed ever since, though not without some struggles.

“The lightbulb isn’t burning out, but the webcams are,” Bramell says.

Livermore residents lovingly refer to the lightbulb as “world famous.” They’re not wrong. Fans from Amsterdam, Australia, Asia and elsewhere log

on daily to watch the bulb’s live stream — although the live stream has failed a couple of times, as the bulb out-sparkled the camera battery.

The bulb took some hits back in the day, when firefighters bumped or tapped the dangling light as they raced from the station on service calls — a precarious good luck tradition the bulb has survived. It also survived its 1976 move from its first home — at the former Fire Station 1 on First and McLeod streets — to the current Fire Station 6 at

4550 East Ave. with a full police and fire truck escort.

In May of 2013, its beam was interrupted for about nine and a half hours when the backup power system, which was supposed to be fail-safe, failed. But the power source was switched, and the light glimmered again.

It’s the oldest light in the world, but it didn’t get that title without some competition. It outlived a 100-year-old light bulb in Fort Worth, Texas; a 91-year-old bulb in New York; a third competing bulb in New

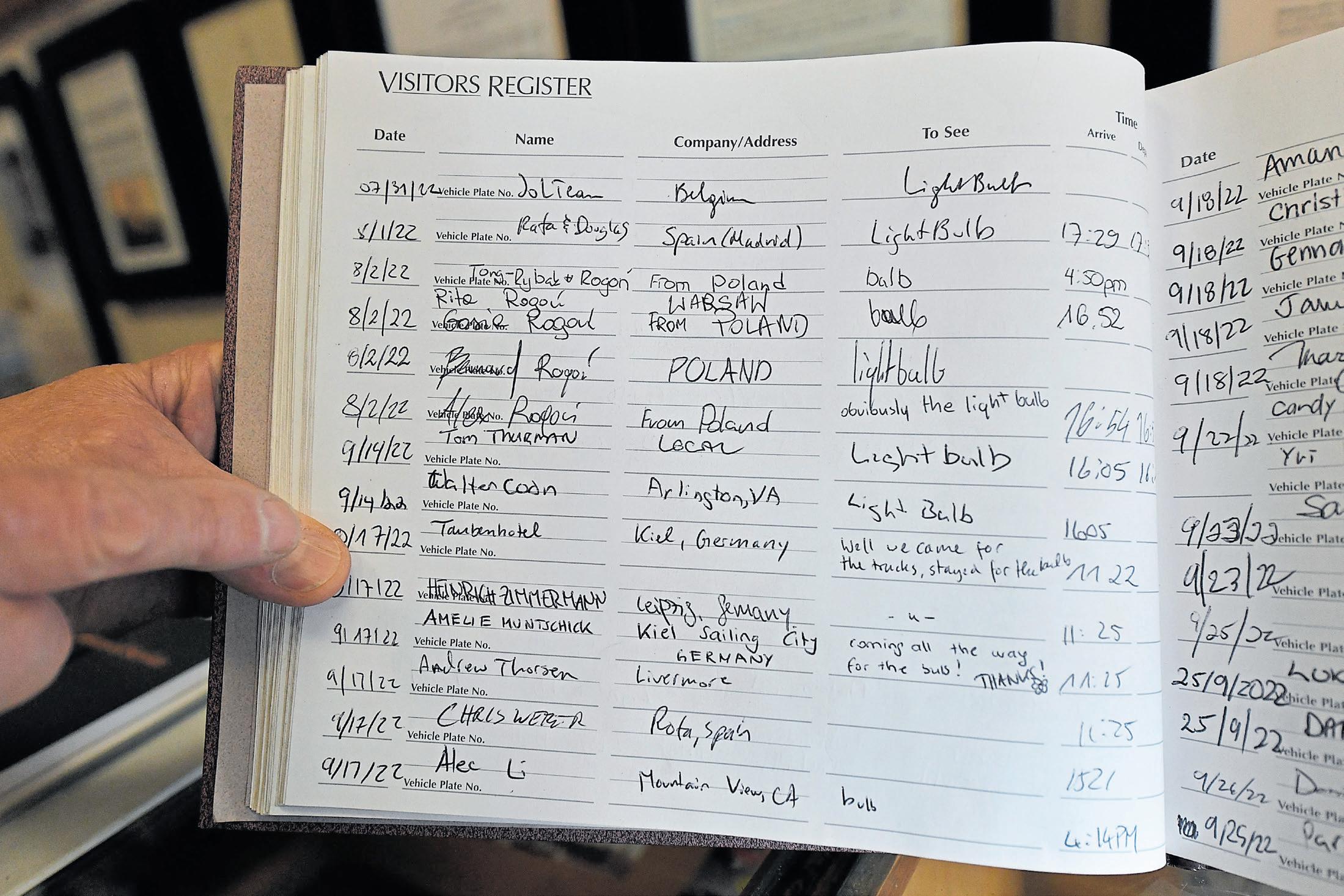

People from around the world have come to see the Centennial Bulb and sign the visitors register at the Livermore fire station.

JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/STAFF ARCHIVES

York City; a fourth one in a Magnum, Oklahoma, firehouse; and another notable rival in Ipswich, United Kingdom, Bramell says.

But will it ever go out?

“Who knows how long it’ll last,” Bramell says. “It could be there another 100 years. It’s just amazing.”

Details: Visit the bulb from 10 to 11:30 a.m. and 3 to 5 p.m. daily, when the fire crew is on-site at Fire Station No. 6, 4550 East Ave. in Livermore. Find more information or watch the Bulb Cam at www.centennialbulb.org.

STORY BY JASON MASTRODONATO

ILLUSTRATION BY PEP BOATELLA

When the sun sets on the Oakland Zoo this month, a new set of animals will come to life.

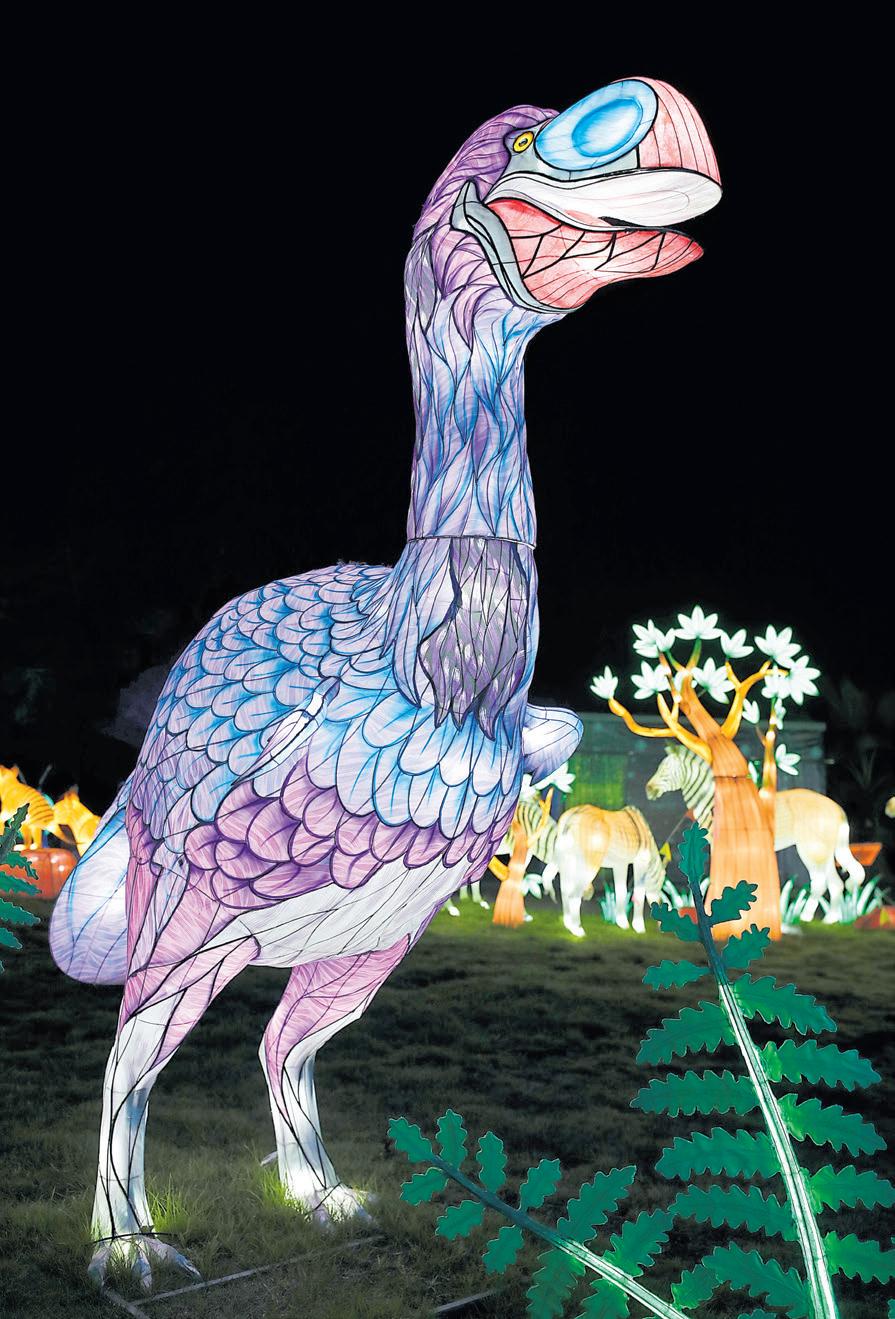

Filled with thousands of LED lights, these illuminated lantern creatures, some as large as 25 feet tall and 65 feet long, will set the imagination on fire. It’s all part of the Oakland Zoo’s Glowfari, and its fifth year promises to be even more extravagant and interactive than before.

“With Glowfari, we tapped into something that was never before seen in the Bay Area,” says zoo president Nik Dehejia. “To see the zoo at night in a very different way, it’s a magical experience.”

It takes a year to produce each year’s illuminated menagerie, from idea generation to arrival at the Port of Oakland. If you’ve strolled the winding paths of the zoo in the last few weeks, you may have already spotted creatures getting ready for their closeups — this year’s Glowfari opens Nov. 8.

The zoo staff dreams up several themes each year, matching them with different areas of the zoo — California coastline fauna, for example, Madagascar flora, deep sea creatures, North American forest animals, alligator-filled swamps and a set of dinosaurs that proved so popular, they’re back for an encore.

Those fantastical creatures come to life, so to speak, at a warehouse in China, where 100 artisans spend about 50 days turning dreams to reality. Painters sketch creatures to fit each theme and its link to the zoo’s conservation efforts.

The glowing lanterns are pretty, to be sure, but the zoo didn’t just

JANE TYSKA/STAFF ARCHIVES

want animal-shaped lanterns. They wanted to connect with visitors in a more profound way.

“At one level, (Glowfari’s) just about coming at night, having fun with your friends and family, having hot chocolate, enjoying what you’re seeing at the zoo,” Dehejia says. “But for those who want to dive deeper, each area has a conservation connection.”

Back in China, metal workers weld immense 3D shapes, so electricians can wire in LED bulbs,before the frames are wrapped in a fabric skin. Then the artists return to add color and details that turn a simple shape into an alligator, a woolly mammoth or exotic bird that looks real enough to come alive, Jumanji-style.

“Thankfully, it’s a revenue share agreement with the company, so we’re not purchasing everything up front,” Dehejia says.

The enormous pieces of art are placed in shipping containers, 20 or 30 at a time, for the 50-day journey across the Pacific Ocean. Shipments begin arriving at the Port of Oakland in August. Once the shipments clear customs, a specialized production company takes the hand-off for the final countdown, installing power cables and prepping the lanterns for their debut. By October, gigantic octopi and fleets of penguins begin quietly appearing on the zoo grounds.

With more than 150,000 visitors each year, Glowfari has become a marquee event for the animal park, which uses the two-month festival to generate a healthy portion of the zoo’s $31 million operating budget and support its conservation efforts.

The zoo has rescued 30 mountain lions, as well as other

JANE TYSKA/STAFF ARCHIVES

JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/STAFF

Top right: A dodo bird was one of the attractions at last year’s festival.

JANE TYSKA/STAFF ARCHIVES

Left: With more than 150,000 visitors each year, Glowfari has become a marquee event for the animal park, which uses the two-month festival to help support the zoo and its conservation efforts.

JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/STAFF ARCHIVES

creatures, thanks to Glowfari funds. It’s not just a priority for the zoo; it’s important to its visitors, too, Dehejia says.

“We’re doing the right thing in how we operate,” he says, “how we care for our animals, how we talk about habitats and climate. Our work around rescuing and caring for species is so important. We know the younger generation and people early in their careers want to come support a zoo that reflects their values and what they believe in.”

Glowfari isn’t the Oakland Zoo’s first foray into holiday events, of course. Its ZooLights delighted visitors for more than 20 years, but over time, the decorations had become outdated, and everything seemed to be Christmas-themed.

The zoo was looking for something fresh and new — “larger than life,” says zoo marketing manager Isabella Linares — when a staffer met Tianyu Art & Culture’s Jessie Li at an Association of Zoos and

Visitors explored a jellyfish tunnel in the California Coastline exhibit during last year’s Glowfari.

JANE TYSKA/STAFF ARCHIVES

Aquariums conference in 2020. The Chicago-based company had just started working with another zoo — and Oakland was game.

Since then, the concept has spread to dozens of zoos, including Seattle’s Woodland Park, the Los Angeles Zoo, Santa Barbara Zoo, Boston’s Franklin Park Zoo and beyond. “But Oakland,” Li says, “was one of the earliest.”

Glowfari’s Oakland debut in late 2020 was an instant success, selling out so swiftly, the zoo has since moved to a rolling ticket release. This year, tickets for the first four weeks dropped on Oct. 22, with an additional 2,500 tickets released at 9 a.m. daily for dates 28 days out.

This year’s Glowfari, which runs through Jan. 26, will include all sorts of new displays — everything from pollinators to high-elevation animals, South American wildlife, exotic birds and Nile Valley creatures. A section devoted to farm animals will include a 26-foot tall,

illuminated walk-through barn. And the dinosaurs are not only back — they’ll be more interactive than ever.

In fact, expect to see more interactive everything.

“Glowfari is one of our longest festivals, and it’s one of our most important festivals,” says Li. “This year, we added a lot more movements in each lantern area. Before, the lanterns lit up, and you’d walk through and take pictures. Based on our research, people like to see more movement and motion from the lanterns.”

In a nutshell, she says, visitors like surprises — lots of them. So look out for giant alpacas and llamas that might come to life, birds that talk and special effects everywhere.

“We changed lighting techniques to make the color more vivid,” Li says. “We added more interactive lanterns (so) visitors can have fun with them. You speak to a parakeet, and it speaks to you and repeats your words. There’s a drum — hit it and it triggers movements. There’s a stepping board (that) triggers lighting. There are swings and seesaws, lantern versions of ‘whack a mole,’ rooms with hanging lights and mirrors that make you feel like you’re in a different world.”

Interactive displays, such as this giant ant walk-through, are just part of the fun at Glowfari. The zoo’s annual holiday event features hundreds of illuminated larger-thanlife animal lanterns.

JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/STAFF ARCHIVES

The goal, Dehejia says, is to delight everyone, no matter their age.

“It’s not just for little kids. It’s for grown ups as well,” he says. “What I love about it is seeing people smiling and happy. We need more fun and joy in our world. That’s what the zoo has always been providing.”

The one thing you won’t find at Glowfari are live animals. The zoo’s residents will be safely secured in their night quarters.

“We’re particularly conscious of noise for some animals,” Dehejia says. “We’ve learned how to ensure we have the sound from our music at a certain decibel level, so it doesn’t affect animals. We work closely with our animal care teams, so where we shine lights, we ensure we’re doing it with great care to the needs of the animals.”

Details: Glowfari will run from 4:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. daily from Nov. 8 to Jan. 26 at the Oakland Zoo, 9777 Golf Links Road in Oakland. Santa will be on hand on Sundays in November and daily Dec. 1-23. Glowfari tickets range from $21 to $39, with a 10 percent discount for zoo members, children and seniors. Find more information at www. oaklandzoo.org.

BY ETHAN BARON

With two simple tricks of the light, the Bay Area’s hidden animal world comes alive at night.

Holding a flashlight at eye level lets people see the reflection bouncing back from different species’ eyes. The color of the gleam can help identify the creature. And an ultraviolet-light flashlight — easy to find online and at less than $15, relatively inexpensive — causes certain animals, notably the creature famous for its pincers and stingtipped tail, to glow in the dark.

“I always think of it like a great party trick for the Bay Area,” says California Academy of Sciences curator of arachnology Lauren Esposito. “There are scorpions everywhere, with the exception of San Francisco.”