6 minute read

Poet, painter, philosopher, naturalist Obi Kaufmann casts a reimagining eye upon our vibrant California

STORY BY ELLIOTT ALMOND PHOTOS BY KARL MONDON

Hiking near his home in Crockett, Obi Kaufmann, a charismatic literary voice in modern ecological science and environment, wanted to emphasize a point. Marveling at how mycorrhizal fungi have survived the six mass extinctions that began 445 million years ago, Kaufmann bent down and scooped up some leafy dirt from below a valley oak, one the author had named Big Auntie.

“There’s more microscopic life in this handful of soil than there are people on the planet,” he said. “That’s how small this life is. So tell me where you stop and where it begins, because life doesn’t work like that. It’s not only interconnected — it’s singular in my dreaming world.”

This is a preamble to a complex set of questions about what it means to be a Californian at this particular moment in time. At the stressful juncture of drought, fire, virus and climate change, along comes a larger-than-life figure challenging our well-worn perceptions with a mixture of hope and admonishment.

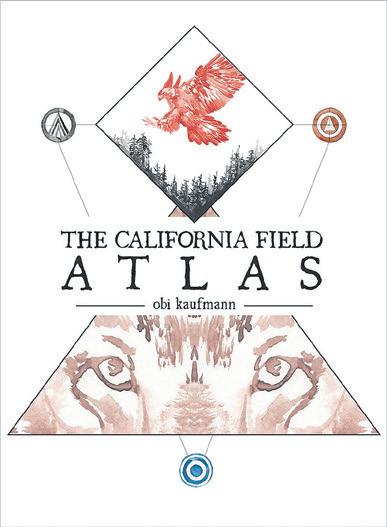

The author of the innovative “The California Field Atlas” and other illustrated books on the Golden State, Kaufmann excavates emotional truths about where we live while painting outside its borders.

I can’t quite define it. Artist, poet, nature philosopher — and conservationist, Kaufmann lives on the corner of imagery and science, inviting readers to reimagine the state through maps and charts of the diverse topography.

“He is talking, exploring and educating about California nature in an open-minded, open-hearted and inspirational way,” said Wade Crowfoot, California’s secretary of natural resources. “He is catalyzing a conversation that I don’t see other people doing.”

The depths of insight and expression in words and watercolor sketches on the page, in geologic charts and timetables of human behavior, revealed themselves at Crockett Hills Regional Park, where Kaufmann, photographer Karl Mondon and I celebrated the first day of fall with a morning ramble above the Carquinez Strait.

Kaufmann, 48, arrived wearing cuffed denim jeans, a faded blue short-sleeved shirt and a widebrimmed straw hat that looked similar to portraits of Ansel Adams. Both arms were covered in geometric tattoos. The hands, from right to left, say “Coyote” and “Thunder,” a nod to the late nature writer Barry Lopez. Tattooed fingers spell out “Wild Life.”

We hadn’t left the parking lot before Kaufmann began ruminating about the natural beauty before us, hopping from fragment to fragment like a jackrabbit. maps of the state’s ecosystems are beautiful artwork and stories unto themselves. They have less to do with cartography than an intellectual dexterity that paints California in unparalleled scope and scale. His watercolor paintings of wildlife, plants, trees, mountains, valleys, lakes and rivers capture sensual scenes of nature.

“This one little corner of woodland is a guardian of an ancient legacy,” he said.

It’s as if Muir, Darwin, Emerson and Van Gogh had been cross-pollinated with a 21st-century sensibility.

Kaufmann’s nomadic lifelong journey into the backcountry has led to sharing observations of California in absorbing prose and paint.

“All day long I do four things: I walk, I write, I read, I paint,” he said. “I have a one-to-one-to-oneto-one ratio. You have to read as much as you write.”

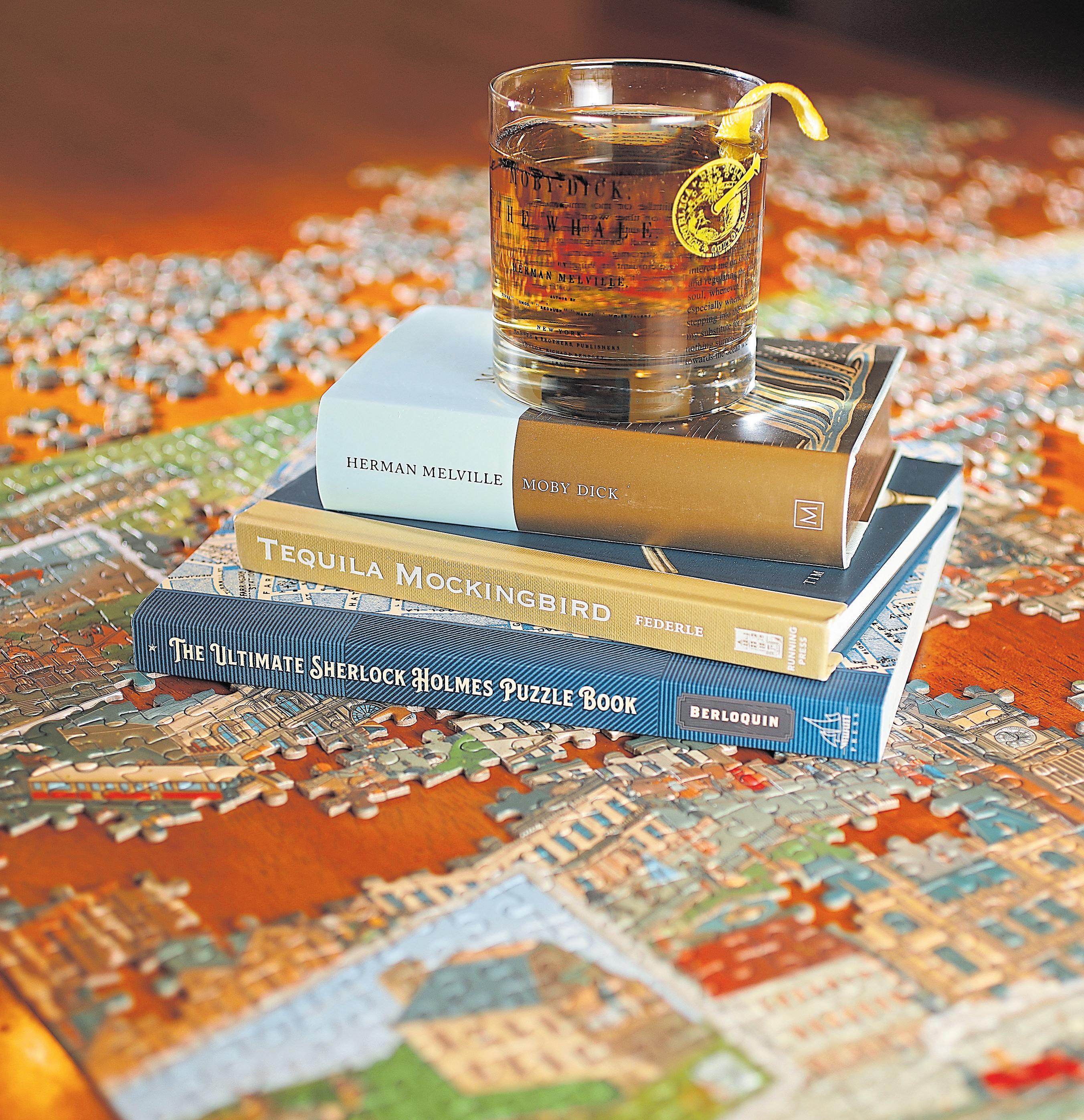

Kaufmann guesses he consumes about 20 books a month, including scientific texts. A mastery of fact-based research gives him the linguistic skill to publish textualized atlases steeped in science but filled with imagination.

Marie Antoine, a coast redwood botanist from Humboldt State University, said Kaufmann “has created a powerful voice for himself on behalf of the wild places.”

“The California Field Atlas” (Heyday Books, 2017) is a solid scientific volume written in spare poetic elegance that gets to the heart of the matter in an accessible way a research text never would.

His hand-painted variegated

Every California household should have a copy of the 608page atlas. It’s not designed as a linear page-turner. I’d start with Kaufmann’s introduction, because it encapsulates the author’s relationship with the landscape he so dearly loves. From there, read it frontward, backward or according to whatever topic piques an interest.

“This might sound funny for a book calling itself an atlas, but I’ve never been interested in the exact where of things,” Kaufmann said. “I’m more interested in the quality of the story across the land. My books don’t tell you where anything is. But they do lay out in great detail the how. How is the layout constructed?

Not the what of a field guide. Not the where of a road atlas. And not even necessarily the why of some history of California. Rather, how these larger systems I’ve organized by the Platonic elements of earth, air, fire and water might tell a better story.”

Kaufmann has burrowed deep into the state’s rich biodiverse core. And then he has gone further. The author followed the atlas with “The State of Water” and “The Forests of California.”

“Forests” is the first of a trilogy that includes “The Coasts of California,” coming in 2022, and “The Deserts of California,” in 2023.

He has sidestepped the trap door of machismo backcountry storytelling that has gained popularity in the past three decades. In all of our conversations, the only anecdote he shared was facing wild pigs on Mount Diablo, where he spent his childhood.

“It’s the one animal I’m afraid of,” Kaufmann said. “They’re just jerks.”

In June, the author took Crowfoot on an overnight outing in the Sierra Buttes. The men spent 18 hours talking about the preservation of natural resources in what became a documentary produced by Wildboundlive.

“He breaks down the beautiful complexity of California nature,” Crowfoot said. “His role is to identify a positive, proactive vision of what California’s nature can return to and then inspire people to help it do so.”

Kaufmann told me he tries to bring together the truth of humanity with the truth of the humanities and physical sciences to create a plausible narrative that underscores what is at stake as our trees smolder and aquifers go dry.

William J. Kaufmann IV was born in Los Angeles, where his father, William III, was director of the Griffith Observatory on the slope of Mount Hollywood. The family moved to Danville in 1977, when he was 4 years old. His father, an astrophysicist, wrote popular books on astronomy and his mother, Lee Johnson Kaufmann, built a clinical psychology practice.

Obi displayed artistry by age 3, his mother recalled. The Kaufmanns sent their son to Seven Hills School in Walnut Creek and later the Athenian School in Danville at the foot of Mount Diablo. Kaufmann spent his leisure time combing the steep slopes of Diablo to explore the natural wonders just beyond the door. He mapped the mountain while emulating J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth depictions.

His mother, who now goes by Jeffre TallTrees, encouraged her son’s artistic predilection. But Kaufmann mostly recalls coming home to calculus homework.

“Dr. Kaufmann’s son was going to be a mathematician,” Obi said. “To him, mathematics is the language of reality.”

He attended UC Santa Barbara as a marine biology major but quickly switched to fine art — and went from Bill to Obi, a nickname his grandmother gave him.

He studied oil painting, drummed in a punk rock band called Glitch and skipped classes to explore the Santa Ynez Mountains above Goleta. Kaufmann discovered Chumash pictographs on those treks in the Los Padres National Forest. The visceral connection to the ancient artwork expanded his boundaries as a painter and philosopher.

Sitting on the dirt trail now with a watercolor pan, Kaufmann shared a postcard-size painting of a coastal live oak that he calls Sunbasket. “I wonder if I showed this painting to Chumash artists 500 years ago, if they would be as bewildered by my depiction of the lines of this life as I am of theirs,” he mused.

After graduating college in 1995, Kaufmann got involved in the Pacific Northwest gallery scene of Seattle and Portland. At age 30, he returned to the East Bay, met his partner, Alli Darling, and transitioned into watercolors while exploring California nature as much as possible. He also worked as a tattoo artist in Oakland.

At Kaufmann’s cramped studio in downtown Crockett, the author yanked titles on fire topics from his wooden bookshelves, when the conversation turned to the blaze burning in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Kaufmann plans to publish “The State of Fire: How, Where and Why California Burns” in 2024. He criticized prevailing methods of thinning trees, saying emerging science is focused on California’s historical relationship with fire.

I confessed my utter frustration as wildland fires have eaten up the state’s forests with an insatiable appetite. Kaufmann stopped me. Californians, he said, have the tools, if not much time, to change course as climate change impacts accelerate at an alarming speed. “You have to love fire as a natural, beautiful part of this,” he said.

He has faith that we will protect what we consider sacred.

To do so, Kaufmann insists we expand our horizons beyond the California hood ornaments of Yosemite Valley, the General Grant sequoia and fairytale forests along Avenue of the Giants. We have to fall madly in love with the oak savannas of the Coastal Ranges, the desert sage, the concrete-imprisoned Los Angeles River.

We must embrace our blemishes as much as our beauty marks, if we’re going to find our way out of this mess.

Kaufmann has provided a roadmap without signposts or trail markers to guide us on this urgent artistic, spiritual and ecological trek toward salvation.

It’s past time to join him.