5 minute read

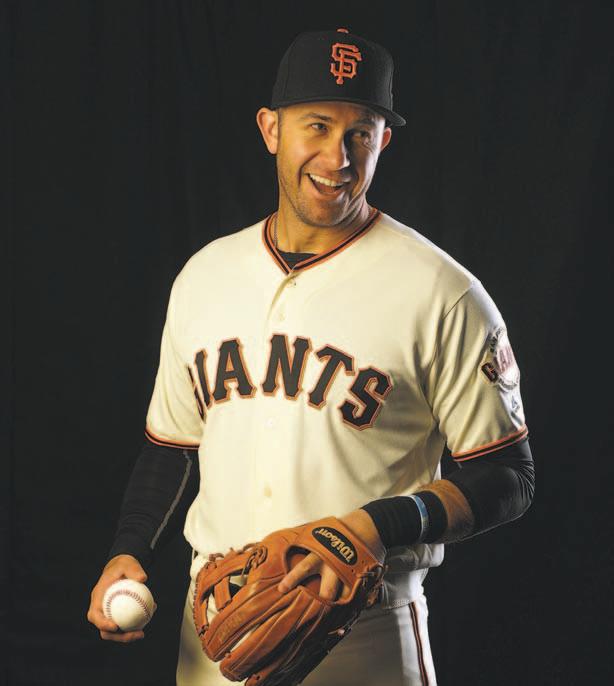

IS HE STILL THE DUDE?

Evan Longoria hopes to prove so for a Giants team that very much needs both his swagger and his production

STORY

van Longoria doesn’t gloat, but he doesn’t lack for confidence either.

From time to time, he’ll indulge reporters and share a few memories from his journey. But to understand how a high school shortstop with zero college scholarship offers became one of the best third basemen of his era, don’t rely on the tales of his scaling a steep hill during practices or hitting the weight room after dark.

Nearly every overlooked player who “makes it” in professional baseball has stories about taking extra swings, extra ground balls and extra sets of squats.

Not every player has Longoria’s swagger. Consider the first home run he hit in the prestigious Cape Cod Baseball League.

“He hit it over the batting cage that was in left field,” coach John Schiffner said. “Absolute monster shot. And he watched it at home plate, and I jumped off the bench and I said, ‘Dammit, run!’ He gets to home plate, and of course guys are high-fiving him, and I said, ‘Don’t you ever do that again,’ and I’m just swearing at him and he said, ‘Aw Schiff, I crushed that … ’ ”

The fact Longoria even played for Schiffner, the winningest coach in Cape Cod Baseball League history, is an underdog story in its own right. Before the undersized infielder — Longoria says he stood 5-foot-10, likely less — fought to find a roster spot in college baseball’s top summer league, he struggled to find a Division I college that wanted him.

“I just wasn’t as physically impressive as some other guys, so I think that kind of gets overlooked,” said Longoria, who at age 32, stands 6-1 and weighs 215 pounds. “I don’t know if there’s another reason, really. I just wasn’t that fun to watch early on.”

Longoria’s college career began at Rio Hondo in Whittier, just a few miles from his Southern California hometown of Downey. Mike Salazar, the coach at Rio

Two summers after no college would have him, Longoria was MVP of the best summer league for college players.

Hondo, said he needed just one look to know Longoria could play.

“The first game I saw he hit a home run, made some good plays and was just solid,” Salazar said. “This guy was legit, and I wanted to have him from Day 1. So I just recruited him hard. We were talking in the dugout at his school, and we just kind of got it going from that point on.”

By the time Longoria enrolled for classes at Rio Hondo, he was already pressing Salazar to open the weight room and the batting cages. He was not, however, begging to run that steep hill near campus, the one they call “MMF.”

Neither Salazar nor Longoria will divulge the name of the hill, but you can infer the first M stands for Mount and the two other words speak to how tough the hill is.

“I’m kind of old school, it’s not just a hill,” Salazar said. “At times, it’s not groomed. So there’s sticks that are five or six feet high, and you just have to plow through it to the top. It’s almost like a hamburger hill, just a straight up, inverted, couple hundred-yard run.”

Salazar said Longoria told him Rio Hondo is where he learned how to hit, but that was where he developed the mental toughness that has carried him for 20 years.

Salazar “would push us to our limits,” Longoria said, “and I remember that being the first time where I was like, ‘Alright, if I want to be the best, I’m going to have to push myself at doing this.’ … It wasn’t even baseball-related. I wanted to be the best at running up a hill.”

A year as a junior college shortstop failed to produce a major college scholarship. USC and Cal State Fullerton made overtures, but neither made an offer.

One coach who did think Longoria could play was Mike Weathers at Long Beach State. Trouble was, Weathers already had a shortstop, a guy named Troy Tulowitzki.

Weathers recalled his first meeting with Longoria.

“I said, ‘Well, we’ve got this guy Tulowitzki playing shortstop. (But) I’ll give you a shot at it.’ And that’s what we did. They worked out in the fall alongside each other, and Evan was plenty good at it. But Tulo was really good and had already been there.”

And that’s how Longoria became a third baseman.

With Tulowitzki and Longoria on the left side, Long Beach State had two future top-10 draft picks on the infield in 2005. That still might not have been the best infield Longoria played on that year. That summer, in Cape Cod, Longoria moved to second base because the third baseman was Todd Frazier (drafted 34th overall by the Yankees) and the shortstop was Chris Coghlan (drafted 36th by Toronto).

“Of course, we were really good,” Schiffner said. “Arguably the 2005 team was the best team I ever had. There was nine big leaguers on the team, and five were first-rounders. It was a great team.”

Two summers after no college would have him, Longoria was MVP of the best summer league for college players. He returned to Long Beach State that fall as a bona fide major league prospect, and that inspired Weathers to coach him even harder.

“I think that ’06 season, because of all the players we had already sent (pro), I thought this kid’s got a really good chance,” Weathers said. “To be third that year in the draft? I wasn’t so sure about that.”

In his final year at Long Beach State, Longoria shared Big West Player of the Year honors with Justin Turner (now the Dodgers’ third baseman). In a draft that included Tim Lincecum (10th), Clayton Kershaw (seventh) and Andrew Miller (sixth), Longoria was taken third by the Tampa Bay Rays.

“Tremendous makeup, but can you project what he’s become? I don’t think so,” Schiffner said. “We knew he was a really good kid, he was a sensitive kid. He was a fun kid, but I don’t think anybody saw that (drafted third overall) at that point in the maturation process.”

In 2008, after only 38 games at Triple-A, Longoria made his major league debut. Then he hit 27 home runs (in 122 games), won Rookie of the Year and helped take the Rays to their first World Series.

Longoria remains the first and only face of the Tampa Bay franchise: a three-time All-Star and a three-time Gold Glove Award winner. His success was born not only of his work ethic, but also, according to Salazar, his hunger for big moments.

“He always embraced being clutch, and he would say that a lot,” Salazar said. “He had this swagger and he would say, ‘Oh, I’m so clutch,’ I mean he would say that when he was 18 years old. I would just say, ‘Shut up, let’s go.’ But then he would clutch up. Twoout base hit to score a run. Boom. And then it just happened and happened and happened.”

After 10 years in one of baseball’s smallest markets, Longoria received a life-changing call this offseason. The Rays agreed to trade him to San Francisco in exchange for Denard Span, top prospect Christian Arroyo and two minor league pitchers, effectively severing ties with their most relatable star, most engaged community presence and most established clubhouse leader.

Now, Longoria is tasked with filling one of the Giants’ biggest holes and saving face for a front office that has pinned its hopes on an aging veteran who might be past his prime.

There’s no telling if this marriage will work, but it feels right. The California-bred player and the California-based team both embarking on a new beginning. And with both accustomed to hearing whispers of doubt, Longoria’s swagger could be just what this team needs.

“If you want to be the dude, you better be able to handle being the dude,” Salazar said. “For him, he always wanted to be the dude.”