12 minute read

ALLGAME a wHOLE NEW

IN COMES FARHAN ZAIDI, OUT WILL GO BRUCE BOCHY AFTER ONE LAST SEASON. IT WAS A CHANGING OF THE GUARD A LONG TIME COMING ALONG THE SHORES OF ORACLE PARK. WILL IT BE A GRAND FINALE FOR THE FUTURE HALL-OF-FAME MANAGER?

STORY BY KERRY CROWLEY

ILLUSTRATION BY STANLEY CHOW

This isn’t the turning of a page – it’s the authoring of a new book.

For a quarter century, Giants lead scribe Bruce Bochy has done it his way. Guided by his gut, Bochy stood at the top step of the dugout while San Francisco penned the golden chapters of its franchise history. But it’s been five long years since that copy went to press, and after multiple failed attempts to keep the story alive, the Giants have found a new lead author.

Farhan Zaidi is the organizational outsider entrusted to script the Giants’ next epic. Once a baseball novice, Zaidi’s creative genius and affable personality convinced the Giants to hire him away from the Dodgers to serve as president of baseball operations.

The arranged marriage between Zaidi and Bochy will only last for one season, but it’s a narrative worthy of close examination.

Bochy is a reminder of where the Giants have been. Zaidi symbolizes where they are headed. Bochy is the captain of the old guard and Zaidi the poster child of baseball’s new age.

Together, the duo will bridge the past and future — with major emphasis on making the most of the present.

They’ll only spend one chapter together. And the writing has begun.

ON

His First Day On

THE JOB, Zaidi was asked whether he’d consider trading ace Madison Bumgarner. “Nothing is off the table,” he affirmed.

And just like that it was clear how different the Zaidi era would be in San Francisco.

“I just didn’t want to rule anything out off the bat,” he explained months later.

The candor was welcome to some fans who desire a full-scale rebuild. It was an opening salvo loaded with fighting words to others, including many diehard season-ticket holders.

But to understand why Zaidi would ever consider parting with a homegrown star like Bumgarner, the curtain must be pulled on his baseball background.

After graduating from MIT and earning a doctorate in behavioral economics from UC Berkeley, Zaidi took a low-level opening as an assistant in the Oakland Athletics’ baseball operations department. It was not a conventional path for a person with Zaidi’s scholastic credentials, but he thrived.

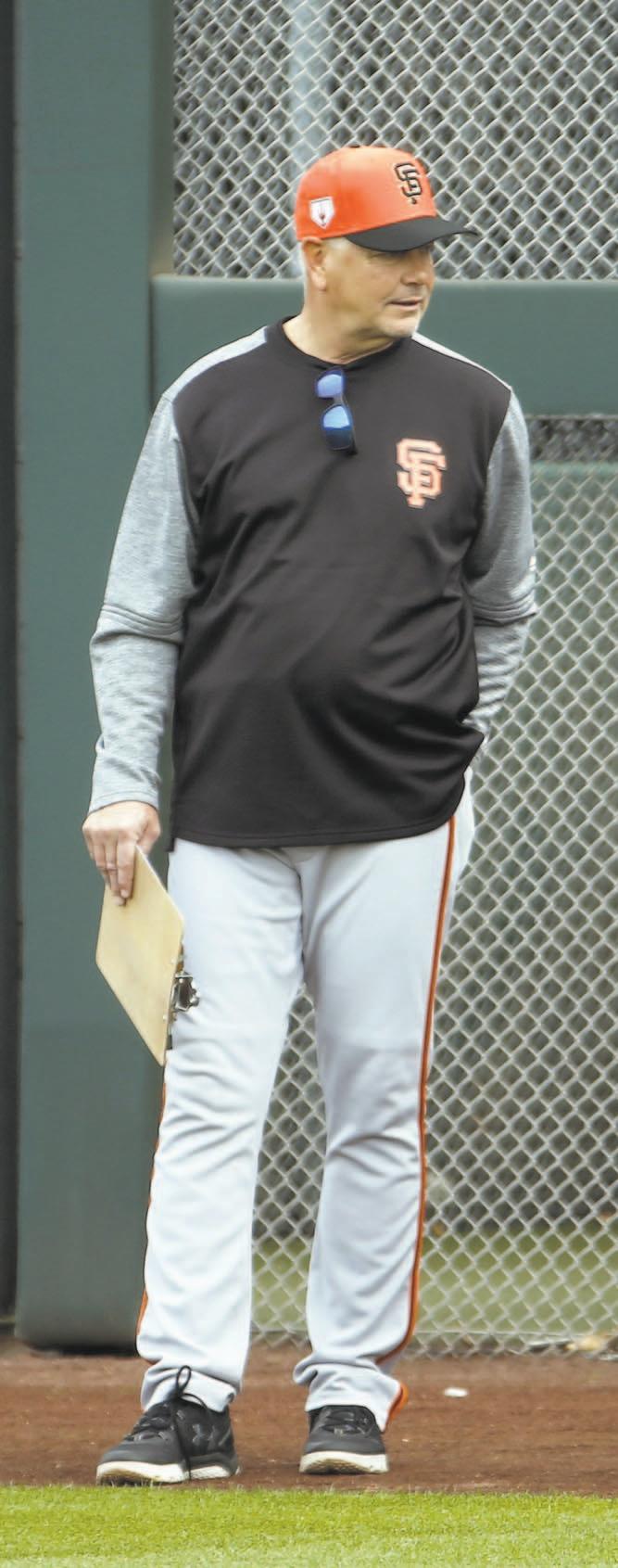

At right: Pitching coach Curt Young and Zaidi spent time at spring training assessing the team’s strengths and weaknesses.

“We hired him when he hadn’t been in baseball and didn’t know what it meant to sit in those rooms and be a part of the conversation,” A’s general manager David Forst said. “He very quickly learned how to contribute. … Farhan, yes he’s incredibly smart and has the Ph.D., but he reads the room too.”

Zaidi ascended through the front office and became the A’s director of baseball operations in 2013. A’s vice president of baseball operations Billy Beane has told reporters he often fended off requests from other teams to interview Zaidi for open jobs, but the Los Angeles Dodgers finally broke through in November of 2014.

Dodgers vice president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman now recounts the myriad ways Zaidi helped L.A. extend a run of dominance in the National League West. Zaidi’s former boss lauded his curiosity and listening skills, but singled out a quality that comes up in nearly every conversation about the Giants’ top baseball executive.

“He is extremely creative,” Friedman said. “He’s got a really good way of connecting with people, and it’s not often you find someone with that intellect and ability to connect with people.”

Creativity has been a constant in Zaidi’s career, a characteristic that proved equally valuable for an A’s organization that often had to pinch pennies and a Dodgers franchise flush with resources.

“He had the best of both worlds as far as the baseball experiences for a front office executive,” former Giants general manager Brian Sabean said. “Oakland has always had to be creative and think out of the box, more so reinvent themselves. And I’ve got all the respect for the Dodger organization. We’ve seen first-hand, they actually don’t get the credit that they should.”

Under the direction of Friedman and Zaidi, the Dodgers retained stars like Clayton Kershaw and Kenley Jansen, but built depth at a level no National League peer could rival. Hidden gems like Chris Taylor and Max Muncy fortified the Dodgers lineup while a stacked rotation withstood key injuries thanks to a deep group of seven pitchers who finished the 2018 season with anywhere from 15 to 27 starts.

Upon his arrival in San Francisco, Zaidi initiated a roster strategy shaped by both his small- and big-market perspectives. In his first five months on the job, he didn’t sign a single position player to a major league contract but devoted countless hours to scoping out low-profile additions.

Zaidi admits he’s willing to overlook perceived weaknesses or flaws of a potential acquisition if they possess traits he thinks provide the most value.

An example: “Take an outfielder who has a plus or double-plus arm,” Zaidi said. “Aesthetically you love to see it and maybe they can impact the game one play a game or one play every other game. But on the flip side, you take a guy that can really control the zone and that’s a skill that comes into play on every pitch that he’s at the plate.”

Command of the strike zone, both for pitchers and hitters, is a commonality among the players the Giants brought to big league camp. Zaidi views the player acquisition process as a balancing act between evaluating the “loudness of a player’s tools” and “the persistence of their impact,” but pitchers who throw strikes and hitters who swing at them have more chances to alter an outcome.

Zaidi’s philosophy on roster building may seem unusual for a club with a pocketbook as hefty as San Francisco’s, but he’s earning the respect of the longest-tenured members of the organization, who didn’t necessarily operate the same way.

“He’s inclusive as far as his thought process, and I think getting everybody in is important,” Sabean said. “Especially coming into an organization you don’t know. He has a vision, and he is knowing what he needs to do in the moment.”

After the team dismissed general manager Bobby Evans — an executive who spent 25 years in the organization — last fall, Giants leadership preached the importance of evolution. The franchise gave Zaidi full authority to fix what’s ailed it, but instead of rushing to replace the engine, he instead invited a handful of new mechanics to coexist with the established members of the front office shop.

The result is a baseball operations department that’s opted for incremental improvements over wholesale changes.

“There’s a lot of institutional knowledge that is really important to have,” Zaidi said. “One of the things I’ve heard from a lot of GMs going into new positions is that if they had any regrets from their first few months on the job, it was not knowing their own players well enough and trading away prospects who wound up doing really well.”

The new operation hasn’t lacked for drama, though. At Zaidi’s request, the Giants pushed for slugger Bryce Harper. They came up short, but plenty of other big decisions loom.

What does the future hold for franchise pillar Buster Posey when top prospect Joey Bart arrives to catch in the major leagues? That’s a good problem to have, Zaidi insists.

“I think if you asked any front office in the game, they’d love to have a timeshare of two guys who are impact bats back there,” Zaidi said.

The Giants won’t face a

Posey-Bart dilemma until 2020, leaving Zaidi with one 6-foot4, 240-pound elephant in the room to confront first. It’s widely assumed Zaidi feels no emotional connection to Bumgarner’s future with the Giants.

Zaidi respects the left-hander’s accomplishments, but he wasn’t a Giants executive when Bumgarner won three World Series. He’s supposed to look at Bumgarner without the bias — without the orange-tinted glasses so many in San Francisco look through.

There’s plenty of chatter about removing emotion from the equation. Zaidi just believes it’s not that simple.

“In Oakland, out of necessity, we couldn’t afford those kinds of relationships,” Zaidi said. “But in L.A., there was certainly more of the resources to do that, and again, there’s some intrinsic value in that that goes beyond how you project a player’s value on the field.”

Zaidi isn’t a clone of those who preceded him. But he’s not the computer-geek, machine-loving nerd he’s often labeled as. His genius is complex, his mind is exceptional, and his gut — believe it or not — is a feature he relies on. Not all that unlike the future Hall of Fame manager who now calls him boss.

A MACHINE TO MEASURE the spin rate of a pitch stood directly behind the mound at Scottsdale Stadium. Another apparatus rested alongside it, so the Giants could track the exit velocity of a batted ball. Then there was an analyst on the field, holding a computer that spit out data in real time.

None of these things — the equipment nor the data analyst — was around for Bruce Bochy’s first spring training as a major league manager in 1995. None were on the field when Bochy managed his first spring with the Giants in 2007.

But as the longest-tenured manager in baseball spoke in the dugout of Scottsdale Stadium on Feb. 18, the technology felt omnipresent.

“I managed with my gut. I came up here in 2007 on my gut, and it’s a gut feeling that it’s time,” said Bochy, who announced he’ll retire after the season. “It’s been an unbelievable ride.”

Baseball is constantly evolving. Despite a popular narrative, Bochy is too.

To suggest otherwise would spread an all-too-convenient falsehood about one of the most successful leaders in the history of the sport.

Sure, the analytical arms race and its presence on a spring training diamond provided an ironic backdrop for a manager who can only be described as “old school,” but Bochy didn’t reach the pinnacle of his profession by ignoring information.

“I think he was factoring in a lot more than he led on,” first-year Reds manager David Bell said. “You can’t have that much success without being hungry for information.”

BOCHY’S GREATEST GIFT as a manager is not his ability to interpret information assembled on a spreadsheet. It’s his ability to interpret the situation at hand, whatever it may be.

That starts in baseball’s most sacred space: The clubhouse.

“He’s always trying to connect with a player, whether it’s a quick hello or a deeper conversation,” said Dodgers manager Dave Roberts, who played for Bochy in the skipper’s first season with the Giants. “He empowers the player and doesn’t try to micromanage. Even for me as a young manager, to try to not impose my will too much on a player or a team, it can be a challenge at times. Boch has that down.”

When Bochy steps away after the season, he’ll become the fifth person in MLB history to manage 25 consecutive major league seasons. The others are Hall of Famers Connie Mack, John McGraw, Tony LaRussa and Sparky Anderson.

Bochy’s players and his managerial contemporaries are skeptical anyone else will join such a distinguished fraternity. As front offices seek to control more aspects of in-game decision-making and strip emotion from the process, managers are more likely to be figureheads than difference-makers.

In a sport where numbers matter more than ever, the personal touch it takes to lead a team is increasingly devalued.

“He’s just a dying breed, you know?” pitcher Jeff Samardzija said. “Unfortunately after this, you’re going to have 30 puppets out there giving you cliche answers, and it’s a shame because Bochy isn’t that. He’s a person. He’s got great stories, he’s a motivator, and on top of all that, he loves his kids.”

For all the discussion about baseball losing a classic character, what’s easily overlooked is Bochy’s innovative mind. Bochy’s strategies didn’t upheave the status quo, but the way he deployed pitchers in postseason play challenged conventional thinking.

In 2010, Bochy gave starter Jonathan Sanchez an early hook in the decisive Game 6 of the NLCS against the Phillies, calling on Jeremy Affeldt, Madison Bumgarner, Javier Lopez and even Tim Lincecum before turning the game over to closer Brian Wilson.

In 2012, he left Barry Zito in the rotation with the Giants trailing the NLDS 3-1 to the St. Louis Cardinals. Zito turned in an unforgettable, scoreless 7 2/3 innings and ignited a series comeback.

In 2014, Bochy took an inning-by-inning approach with Bumgarner in Game 7 of the World Series. After the sturdy left- hander allowed a ninth-inning triple, Bochy stuck with his ace, who clinched a title with five scoreless relief innings in what’s considered one of the great postseason performances of all time.

“You just couldn’t make a mistake against him,” Rockies manager Bud Black said.

Black recalls dozens of games, particularly in the Giants’ home park, where he was left searching for the ideal late-game matchup. He wanted his right-handed pinch-hitters to face Bochy’s left-handed relievers and for Bochy’s right-handed relievers to see Black’s left-handed bats. * * *

MATCHUPS MAKE A DIFFERENCE late in games. So does thinking ahead, and Bochy is unrivaled when maneuvering in the final innings.

“It seemed like for forever he was going to get (Jeremy) Affeldt on Adrian Gonzalez,” Black said. “He was going to get Javier Lopez on someone. Here comes (Sergio) Romo. Here comes Brian Wilson.”

Even Torey Lovullo, the thirdyear manager of the Arizona Diamondbacks, understands Bochy’s brilliance. The Giants have lost 187 games since Lovullo took over in Phoenix, but he’s rarely felt like a win against Bochy’s club came easily.

“After a game against the Giants, I’m exhausted,” Lovullo said. “You better bring your ‘A’ game because if you don’t, he’s going to exploit you. He doesn’t just exploit you one time. He will try to exploit you with a body blow, a jab, a left hook, a right hook and then a power shot to knock you out.”

Bochy is considered one of the greatest postseason managers of all time, but his players suggest his ability to hold a clubhouse together during the regular season is just as impressive.

Samardzija said he marveled at the way Bochy went about his business during the Giants’

Five Potential Replacements For Bochy

MIKE MATHENY: Chastised for his bullpen management skills in St. Louis, Matheny was let go by the Cardinals despite posting a .555 winning percentage over six-plus seasons. The former Giants catcher has a pennant and a 100-win season under his belt plus the necessary experience to handle the pressure to win in San Francisco.

HENSLEY MEULENS: Third base coach Ron Wotus and farm director Kyle Haines are the other top internal candidates to replace Bochy, but Meulens is a strong choice. He earned rave reviews for his work managing the Netherlands in the World Baseball Classic and was a finalist for the Yankees job that went to former ESPN analyst Aaron Boone.

JOE GIRARDI: If the money was right, Girardi would be calling shots from the dugout instead of watching games from home. Instead, he’s the rare high-profile candidate who could be lured back with hefty compensation and the allure of working in a big market with a big budget.

RAUL IBANEZ: A special assistant in the Dodgers organization, Ibanez knows Farhan Zaidi well and could be hand-selected by the new president of baseball operations in San Francisco if he wants a younger presence who understands the mission of the front office. Zaidi doesn’t have the same connection with Omar Vizquel, but the former Giants shortstop is another recently retired player with a name to watch.

BOB GEREN: Geren’s track record in the game and his ties to Zaidi suggest he’ll at least receive some consideration in San Francisco. He’s been the bench coach in Los Angeles under Dave Roberts and served as the manager for Oakland for five years, so few executives know Geren better than Zaidi, who spent considerable time with the A’s and Dodgers.

— KERRY CROWLEY

collapse at the end of the 2016 season while starter Derek Holland suggested the team would have been worse than 73-89 last year if not for Bochy’s leadership.

A manager’s impact on a team’s overall record is impossible to quantify statistically, but the Giants will need Bochy’s 25th season in baseball and 13th with the club to be one of his best. The Giants have suffered through consecutive losing seasons for the first time since 2007-2008 and a moribund lineup hasn’t received any significant additions.

Despite the bleak overall outlook, Zaidi is determined to provide Bochy with a versatile roster that maximizes the manager’s in-game skills.

“I know how much Boch wants to go out with a strong year and obviously that’s a huge motivation for me and all of the players,” Zaidi said. “Not that any added motivation or inspiration is needed for this group, but we’re very focused on this season.”

It’s possible changes across nearly every level of the organization inspired Bochy to reconsider his future, but he told reporters he began contemplating retirement at the end of last season. Bochy vehemently denied the possibility that a new regime with a different agenda convinced him to step away from the Giants, but he also wouldn’t rule out the possibility that his days in uniform aren’t over.

Bochy is a baseball man’s baseball man, a player’s coach and a fierce competitor. It shouldn’t come as any surprise that after announcing his retirement, the future Hall of Fame manager had no desire to cycle through his favorite memories or recall specific moments that defined his career.

No, Bochy’s mind didn’t race. It instead settled on the target that’s motivated him for the last quarter century: a ring.

“I look forward to one more shot,” Bochy said. “Trust me. I’m all in.”