8 minute read

max ebb: every dog's dna

"Not again!" I groaned. "Why, oh why does it always have to be on my dock?" The offending object was a perfect specimen of dog poop. It had happened before. I had complained to the Harbormaster, but there are several liveaboard dogs on the dock, and without positive evidence linking the calling card to the dog who left it, marina management was powerless to take action. I uncoiled a few turns of hose, turned on the faucet, and began to wash the offending material back into the Bay when a shrill female voice caught me all standing. "Max!" the voice shouted. "What are you doing? Stop!" It was Lee Helm, graduate student in naval architecture and a known treehugger. Instantly a long train of thought fl ashed through my consciousness. Sure, I guess if I were a good citizen I should walk all the way up to the marina park, fi nd a doggy poop bag dispenser that wasn't empty, bring a bag all the way back down to my boat, collect the poop, and walk all the way back to the trash bins to get rid of the thing and then all the way back to my boat. But it wasn't my dog, and it wasn't my dog's poop. Furthermore, as various so-called boating advocacy lobbying groups used to insist back in the day when they were fi ghting hard against laws prohibiting overboard discharge, it's a tiny bit of pollution compared to industrial and municipal sources, and a tiny bit of pollution compared to other biological sources like sea lions, birds and fi sh. It is "to diaper a seagull," as one particularly memorable editorial in a long-gone sailing magazine summed it up. All this in the fraction of a second between hearing Lee Helm's voice demanding I stop, and the stream of water knocking most of the dog poop into the harbor. It was all gone and the dock was clean again by the time Lee had run down the gangway and reached my berth. "Gosh, Lee," I started to explain, feigning involuntary carelessness, "since this isn't from my dog, it didn’t even occur to me that I should have disposed of it properly. It's annoying enough just fi nding it here next to my boat." "No, Max, that's, like, not the point," said Lee, catching her breath. "You need to save a sample. Then the marina can fi gure out who done it." "Really?" I said. "They can do that?" "For sure," Lee informed me. "I just read this in the new regulations for liveaboards: If you have a dog, you have to submit a saliva sample to the marina offi ce. They send the samples of all the dogs to a commercial DNA lab, where the results stay on fi le. Then, when you fi nd something like you found just now, you send in a sample and they match it to one of the known dogs." "I didn't think the marina had the budget for that kind of thing," I said. "It's not expensive," Lee informed me. "There are a few competing companies that offer the service — and they have great names: There's PooPrints, there's Mr Dog Poop, and there's DogPile ID. That last one is run by the U.C. Davis Veterinary Genetics Lab. It's really intended for condo complexes and residential associations where they have some control over most of the dogs in the nabe. But, like, with a marina, with all the docks behind gates, it's a fi nite set. We know exactly which dogs are suspect." "How do I buy in?" I asked. "It would be worth a lot not to fi nd this stuff on my dock every so often." "No cost to the berther, at least not directly," said Lee. "The marina pays about $30 or $35 for each dog that it adds to the DNA database. They make this a requirement of being a liveaboard with a dog. It's just a saliva swipe, easy to do. Then, when there's an offending pile, you ask the marina offi ce for a sample bag, put in a small amount of poop, and they send it off to the lab. Cost of the DNA match is between $50 and $150, depending on which vendor they use."

Advertisement

"And once the offending dog is nailed," I added hopefully, "the owner is evicted from the harbor?" "Possibly," said Lee. "On the other hand," I said after thinking it through for a second, "I imagine the fi rst positive match and a warning usually puts an end to the problem, since denial won't work anymore." pulling its human, whom I recognized as one of my liveaboard dock neighbors, rapidly down the dock in our direction. "Suspect number one?" Lee whispered. "Could be," I said as the dog abruptly stopped at my dock fi nger, ran right over to the spot that I had just cleared of the deposit, and gave the dock surface a very careful sniff. "You think that dog knows something that we don't?" I asked the owner, trying not to sound too accusing. After all, the dog's human was one of the more congenial liveaboards on our dock, a good neighbor and a frequent volunteer at the yacht club. "Fido hasn't been off the boat all morning," she answered, pulling the dog back to the main walkway by its leash. "But that nose doesn't miss a trick, so something interesting was there recently." "Yup," I confi rmed. "Third time this month. A real steamer..." "We have an Astroturf pad on the foredeck," explained the liveaboard, "so even in a potty emergency, the poop is pretty much under control. I do have my suspicions about who the offender might be, though."

After thousands of years of selective breeding, some dogs actually like 'messing about in boats'.

"How did you get your dog to start using the Astroturf?" asked another one of my dock neighbors who stopped by to pet Fido and join the conversation. He was not a liveaboard, but he told us that he had a dog, and that he had to harborhop up and down the coast because the dog absolutely refused to use any of the onboard facilities, regardless of incentives or punishments. "He once held it for 19 hours going up the coast from Morro Bay to Monterey," he said. "But he's a smart dog, and now he just refuses to eat or drink on the boat." "The secret is the smell," suggested the woman with the black lab. "You have to get another dog to pee on the pad fi rst, because they like to go where another dog has gone before. That's a diffi cult enough assignment, actually, but there's a lot of good advice on the Web about how to do this." "I'll try almost anything," he replied. "I can't sail off to the South Seas until my dog learns to do it on board. And I can't sail in very strong wind either, because when the boat leans over, my dog starts skidding around on his claws. So we end up using the motor alot." "When the skipper is nervous, the dog is nervous," observed the black lab's human after the wouldbe ocean voyager was out of range.

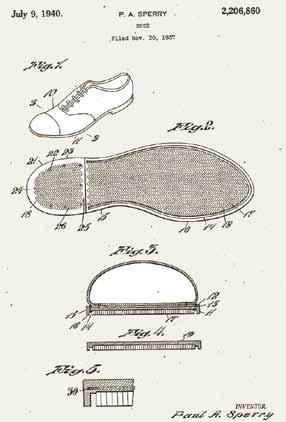

When a dog relaxes, the pads on its paws are very good at nonskid." "Isn't that where Paul Sperry got the idea for the non-skid herringbone pattern in the original

Topsider boat shoe?" I asked. "Back in 1920-something?" "Fact check!" exclaimed Lee, pulling out her phone. "It won't surprise me if this is another apocryphal myth," I predicted. "Hey, it's true!" Lee announced with some surprise, after only a few seconds of Internet browsing. "Except it was 1935, not in the '20s.

According to the Sperry website, that is." The dog owner bent down and extended her hand, which the black lab took as an invitation to shake hands. This gave her a chance to examine her dog's paw pads in detail. "I don't really see a Topsider sole," she said. "But it does have little ridges." "Wikipedia confi rms it too," Lee added after a few more taps on her phone. "And Sperry's dog was a cocker spaniel named Prince." "Well, then, thank you Prince," I said as I looked down at my Topsider moccasins. "We better be off," said the woman with the black lab. "Fido has some urgent business to attend to in the park." "That must be awful," I said to Lee, still thinking about my other dock neighbor who could not sail overnight because of his dog's shore-leave requirements. "I dunno," Lee surmised, "I think maybe some people use their dog's short endurance and lack of sea legs as an

excuse to make only short coastal hops and never go too far offshore. They feel safer close to land. But, like, it doesn't compute. Sailing is way safer offshore, with nothing to hit and a lot less stuff to hit you."

Istill had the hose in my hands, so I gave the dock a few extra high-pressure squirts to try to wash away the smell, hoping to make my dock less attractive to another dog for more of the same. "I wonder what else they can tell you from a dog's DNA," I thought out loud. "I imagine they can send you a nice pie chart sorting out which breeds your mutt is made of, sort of a dog version of 23andMe." "39andMe," corrected Lee. Dogs have 39 chromosome pairs. Humans only have 23." "That’s why they have so much more common sense than we do," I suggested. "It explains why they have to be selectively bred for thousands of years, just to get them to like sailing." — max ebb

The original patent application for the Topsider boat shoe sole. You be the judge: Does the illustration above look like your dog's paw?