8 minute read

Innovations in Fire & Explosion Protection

BY KEITH LORIA

Improvements and innovations in fire and explosion protection have come at a steady pace in recent years, as more companies are investing in products to make things safer and easier while complying with regulations. Pellet Mill Magazine spoke with five industry experts about the latest trends, innovative products and what they believe should be future priorities. Interviewees include: Jeramy Slaunwhite, chief technical officer, explosion safety for Rembe Inc.; David Grandaw, vice president of sales for IEP Technologies; Allen Wagoner, president of FLAMEX Inc.; Jason Krbec, sales engineering manager for CV Technology Inc.; and Eric Peterson, CEO of Fagus GreCon Inc.

PMM: What do you think has been the most significant innovation in fire and explosion protection in recent years?

Slaunwhite: Holistically, the higher awareness and regard for dust explosion hazards and mitigation strategies in industrial processing facilities have greatly improved. Considering combustible dust fires and explosions have been occurring for as long as dusts and powders have been handled, the development and refinement of flame-arresting technology over the past few decades has provided feasible explosion protection solutions for many facilities and industries. Flameless venting allows for reliable explosion protection without harmful fireballs and pressures inside buildings and occupied areas.

Krbec: The most significant innovation is the more costeffective and advanced design isolation systems, specifically explosion isolation systems for the inlet lines to dust collectors and also the clean air exhaust return lines from dust collectors. We’ve seen more reliable solutions developed, as well as some really improved testing standards for those type of products. It’s been a point of emphasis, because it’s where we see one of the largest gaps in the process industry.

Grandaw: The electromechanical suppressor used for active explosion suppression and isolation systems. For many decades, all styles of high-rate discharge extinguishers used for explosion suppression or isolation systems used some version of pyrotechnical device to activate, such as electro-explosive actuators or gas cartridge actuators. Besides the safe handling considerations necessary for these types of devices, there were often challenges with shipping, as some of these devices required special licensing. In addition, most of the pyrotechnical actuating devices required periodic changeout to ensure proper operation of the extinguisher.

Peterson: As everything gets a little more technically advanced, having things become more intelligent and smarter on their own—as we struggle with labor and a lot of different parts and pieces—is important. The interconnectedness and equipment that delivers things just a little bit easier is very helpful. It’s still new in the fire and explosion side of things.

Wagoner: It’s a broad area, and encompasses a lot. A number of processes employed in the manufacturing of wood pellets present a fire and explosion hazard that must be addressed to ensure workplace safety, protection of assets and avoidance of downtime. Drying and hammer milling of wood material are particularly conducive to the generation of sparks and fire within the pneumatic transport system. Other processes such as pelletizing, pellet cooling, screening and product load out are also subject to possible ignition from sparks, overheated pellets and mechanical friction sources. To combat the all too common problem of dust collector fires and explosions in woodworking industry, we pioneered the use of a new technology in North America by introducing the FLAMEX Spark Detection and Extinguishing System in 1977. Since that time, thousands of have been installed in a variety of industrial facilities across North America, including many medium and large industrial wood pellet operations.

PMM: What product or service designed for this space is your company the proudest of?

Krbec: We developed a completely passive isolation device for clean air exhaust for dust collectors, and one that uses the same technology as our flameless vents—to have an isolation point that doesn’t require any moving components. We call it the Interceptor–QV and developed it a few years back, and we have had a lot of success with it in various industries—not just biomass. It’s won a couple of design awards for safety products.

Grandaw: From a product standpoint, it would be our SmartDS detection system. Most explosion suppression or isolation systems use pressure-activated explosion detectors to initiate explosion control. This is a detection method well proven for many decades. With the SmartDS system, we use a rate-of-pressure rise detection technology that is programmed to respond to explosive rates of pressure rise, thus minimizing false actuations due to process pressure issues. The system has a history buffer that provides graphical evidence of the pressure increases just prior to and during any event leading to a system discharge. This is a great investigation tool for determining that an incipient explosion has been suppressed, resulting in the post-event investigation focusing on corrective action to address the ignition source.

Slaunwhite: At REMBE, one of our major shining achievements is the development of flameless venting technology for dust explosion venting, several decades ago with the Q-Rohr. This has led to our Q-Box flame arrestor and particulate retention device, a flameless explosion vent.

The Q-Box is a versatile, economical and third-party tested and certified solution for safe indoor explosion protection in many industries, including food and wood processing.

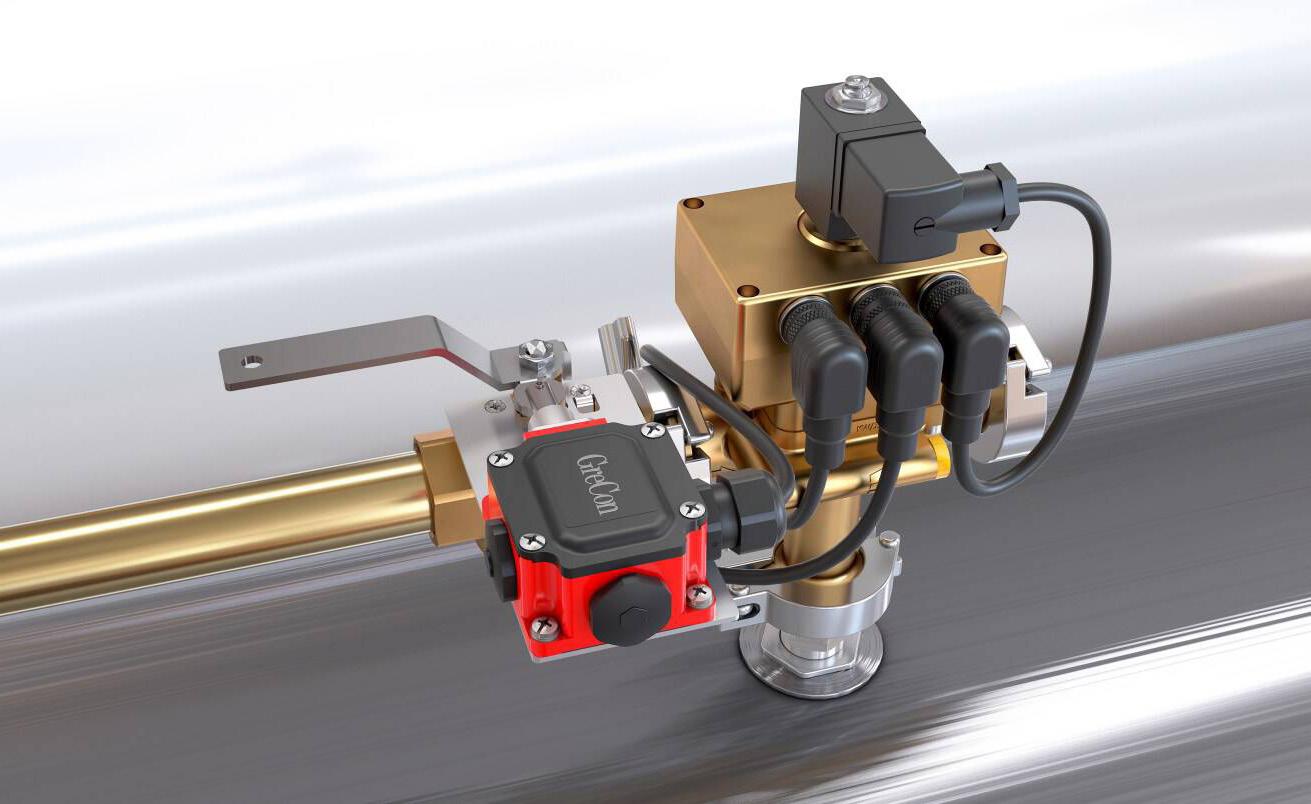

Peterson: One is a spark detector that has been on the market for about a year and a half. It can basically adapt whether there’s light or not, and actually gets smart and adjusts to the light over time. So, if there’s a hole in the duct work or a flap that opens up, historically, the sensor would just fire off. This one will get smart and realize there’s a certain amount of light, and adjust to it. That type of detection obviously has a lot of benefits for anyone who has extraneous light. The other is GreCon IEM, an intelligent extinguishment system that we just came out with this year. It will monitor the wear of the nozzle and it will also monitor the flow. It helps with proactive maintenance.

Wagoner: Our extinguishing turbine, the MXOne Firefighting Turbine, represents a new generation of stationary firefighting. The system has a 360-degree operating range and allows the application of water mist from a long, safe distance and with high accuracy. When extinguishing a fire with water mist, the water is atomized under high pressure, producing a dramatic increase of water surface which allows a greater efficiency in the absorption of heat. When water evaporates, its volume is increased many times over, which causes a cooling and suffocating effect on the fire. The volume of water consumed during the firefighting effort, as well as the consequential damage caused by the water, are extremely low. The control and direction of the extinguishing turbine can be done fully automatically upon detection by IR Flame Detectors, remotely by mobile devices or manually. Various stationary and mobile control variants can be implemented according to the operator's requirements.

PMM: What aspect of fire and explosion protection could use improvement?

Slaunwhite: In my opinion and observations, the most widespread shortfall regarding combustible dust explosion safety is the do-it-yourself approach to protection equipment with a “good enough” mentality. There are recognized standards for design, performance testing, application and reliability of explosion safety equipment that ensure the equipment will do its job if called upon. The nature of dust explosions is highly chaotic. As such, these standards use testing and calculations based on actual explosion testing to ensure reliable protection. In a high quantity of site inspections, especially in the wood industry, I have observed uncertified and undocumented explosion relief vents and isolation devices, often with visible deterioration. Unlike other fire safety system such as sprinklers, which must be designed and certified by an engineer with listed and approved components without question, dust explosion protection is too often under-designed with no accountability, using questionable equipment. The awareness and standards have certainly been evolving over the past few decades, as has much of industrial technology.

Grandaw: Regular periodic inspections of fire and explosion protection systems. While it is true that these systems are designed for use in the challenging conditions found in industrial plants, if these protection systems are compromised due to lack of proper maintenance, process equipment damage, injury to personnel or worse can happen. Fire and explosion protection systems are like other processrelated equipment, needing periodic inspections, and sometimes component replacement when compromised.

Krbec: One of the major things that need to be improved is some of the training and awareness of protection systems themselves. A lot of that goes to the plant operations side. Much of the explosion and fire protection systems are not completely hands-off; they do require some understanding of how to operate and use them properly if you’re doing certain types of process activity. That communication and training is still one of the big gaps we see.

Peterson: One of the big challenges is that most everything in today’s systems and facilities is all wired. There isn't a lot of wireless. Being able to move into some sort of cloud environment where we can go into a lot of different places and not have everything connected back to a system would certainly be extremely beneficial from a time, cost and maintenance perspective. Anything we can do to start connecting these pieces would be big plus.

Wagoner: Owners or operators of a facility where materials determined to be combustible or explosible are present in an enclosure are responsible for obtaining a dust hazard analysis (DHA) in accordance with NFPA 652, Chapter 7. A DHA is a written document that is prepared by a qualified individual to identify specific hazards in the facility, and to provide prescriptive measures to be taken to address those identified hazards. The DHA is to be re-

Fire & Explosion »

viewed and updated every five years. Many facility owners are unaware of this requirement or have failed to take steps to have one conducted. It is widely believed that this is the first step in addressing the dangers of potential fires and explosions that are largely inherent in facilities that handle combustible dusts.

Author: Keith Loria Contact: asimet@bbiinternational.com

In an article dated May 11, 1982, United Press Canada reported that BioShell Inc.—a wholly owned subsidiary of Shell Canada Ltd.—was planning to build a “wood densification plant” in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, to produce fuel pellets from wood waste. The plant was to be the first of its kind in the province, but similar to others the company had in Hearst and Iroquois Falls, Ontario, including BioShell’s initial densification operation—a sawmill residue-to-brick plant that was built in 1980. The Lac-Mégantic plant would come at a price tag of about $5.7 million and have an annual capacity of 105,000 metric tons of finished product. Construction was to begin “immediately, with the plant scheduled for a start-up in December 1982.”

Fast-forward 42 years, and that plant is still operating, a relic and one of the oldest mem- bers of the North American wood pellet plant family. And, as demonstrated in local newspaper archives, the first shipper of transatlantic wood pellets (see sidebar). The plant has not changed hands much over the years; BioShell owned it for just over a decade. For Bruce Lisle, buying the plant from BioShell at an opportune time when Plan A didn’t come to fruition has resulted in a 30-plus-year career in the industry.

Working Up Plans

“I was actually looking at coal briquetting in the mid-80s, and I formed a relationship with a guy who had developed a binder to briquette coal fines—it was so clean you could put a briquette in your pocket and not turn it black,” Lisle tells Pellet Mill Magazine. “My deal with him was to build a plant in Canada, in Nova Scotia, which had coal mines at the time.”

Lisle met his wife during his work travels and subsequently moved to Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, where he began working with the Nova Scotia Research Foundation to conduct a residential market study for those coal briquettes. “It was a great product, but nobody would buy it because there just weren’t many coal clients,” he says. “In the meantime, I read an article on wood pellets in what was then called Wooden Energy—which ultimately turned into Hearth & Home Magazine—and they said it was a bullseye. Long story short, I