10 minute read

COPRODUCTS

FiberFrustration

The U.S. EPA hasn’t approved a corn fiber pathway in more than four years, but hope is renewed with a new administration. Meanwhile, NREL has pitched a new cellulose volume measurement method to help address EPA’s concerns with accuracy. By Lisa Gibson

The stalled U.S. EPA approval of corn kernel fiber-to-ethanol pathways could be having a $1 billion impact on a 15-billion-gallon-peryear ethanol industry, says Jim Ramm, director of engineering for EcoEngineers. That’s

assuming 3% of overall production could be from fiber and a $2 premium. It’s worst-case scenario, yes, but it’s realistic, nonetheless.

EPA approved its last fiber-to-ethanol pathway in December of 2017. At that time, EPA, led by Administrator Scott Pruitt, outlined concerns around the accuracy in measuring the cellulosic portion of ethanol production. The slammed door has forced ethanol producers to distribute their cellulosic volumes to California or Oregon markets (where fuel standards recognize the pathways), and technology developers to overcome the volume measurement challenge.

“I think that the industry has really responded to that in terms of the methods that are out there,” Ramm says. “The methods that are out there can demonstrate high degrees of accuracy. It’s really accurate in terms of determining the converted fractions of starch and cellulose in the fermenter.”

The first five pathways approved before December 2017 were Edeniq 1.0. “That was a baseline methodology and really

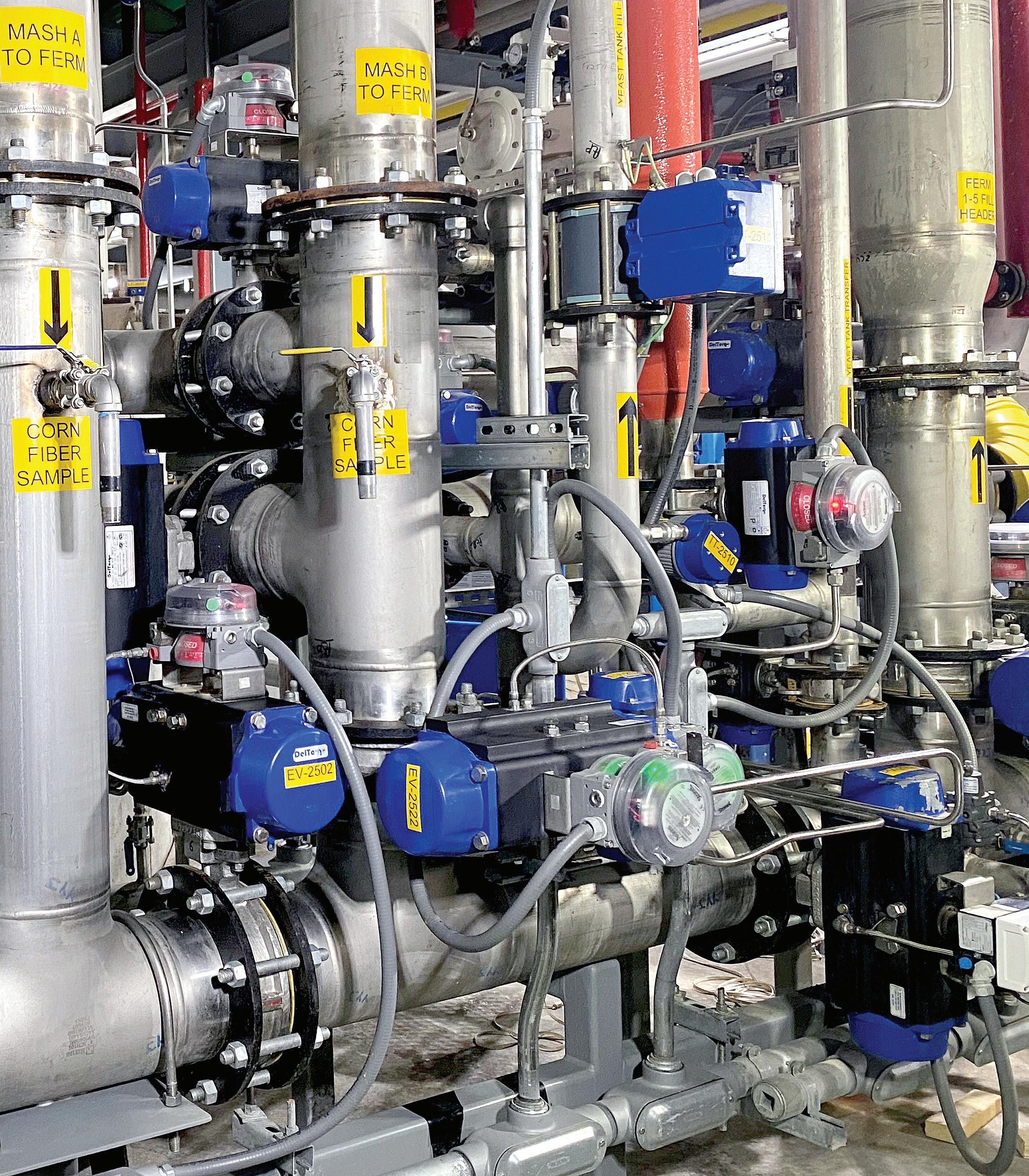

FIBER PIPE: Corn fiber-to-ethanol pathway approvals were shut down in 2017, under then U.S. EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt. Elite Octane in Atlantic, Iowa, is one of many plants with corn fiber-to-ethanol capabilities that have applied for approval under new EPA Administrator Michael Regan’s leadership. And some plants that had applied before 2017 are reapplying.

METHOD MAPPING: Justin Sluiter, a researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, studies cellulose measurement processes in NREL’s Analytical Characterization Lab. Sluiter and his team of researchers were tasked to find an improved method of measuring corn fiber ethanol volumes. (60926.jpg)

PHOTO: DENNIS SCHROEDER/NREL very few of those pathways are still operating today,” Ramm says, adding that developers, including Edeniq, are now offering non-baseline pathways. Edeniq executives declined to be interviewed for this article.

“The industry has moved on to pay attention and focus on California,” Ramm adds. “California has been very supportive and has included these gallons in their tier 1 GREET (Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions and Energy use in Transportation) model and continue to approve pathways and gallons into California.”

EPA’s outdated GREET model is the problem, says Nick Bowdish, president of Siouxland Ethanol LLC in Jackson, Nebraska, and Elite Octane LLC in Atlantic, Iowa. Both plants have corn fiber capabilities recognized in California. “GREET is one of many items the EPA can take action on right now.”

The Accuracy Issue

The problem is complex, says Justin Sluiter, a cellulose carbohydrate chemist at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. And it starts with variations in starch measurements. It’s easy to mislabel starch as cellulose when working with a poor starch assay, he says.

The current methodology uses acid hydrolysis to compare a batch of starch glucans to a batch of both starch and cellulose glucans, thereby estimating overall cellulose glucans. So, a poor starch glucan measurement results in an inaccurate cellulose measurement.

With this concern in mind, Sluiter conducted a test of industry labs. “We solicited analytical labs that claim to be able to measure starch well,” he says. “Each was to measure and tell us how they did it. The labs struggled to get anywhere near the real value. That is concerning to me because measuring starch can end up contributing more to cellulose. I believe these data was what concerned EPA. What I would want to see is the labs having some agreement.”

ONLINE FUEL ETHANOL DIRECTORY

SEARCH ETHANOL

E EQUIPMENT

INDUSTRY COMPANIES

EXISTING G PRODUCERSERS

EMPLOYMENT

CONSULTING NG

FUTURE PRODUCERS

CLEANING

Sluiter pitched a better way, but EPA was more concerned with finding a cellulose-specific method that doesn’t compare cellulose glucans against starch glucans.

After more than a year of research, Sluiter released a publication earlier this year, “Direct determination of cellulose glucan content in starch-containing samples,” outlining a new measurement method that removes compounding errors of the two-measurement methods, according to his paper. But the new method does overestimate cellulose when yeast bodies are present, he adds. “I did not have an assay available to measure yeast body glucans accurately.”

Sluiter’s paper describes his method as a “concise in-series procedure with minimal measurements. Sample preparation consists of a starch extraction employing enzymatic hydrolysis followed by a simple filtration and wash,” the paper continues. “The samples are then subjected to a two-stage acid hydrolysis. The concentration of glucose is determined by ion exchange high-performance liquid chromatography with a Pb2+ column and a refractive index detector. The cellulosic glucan content is calculated based on the initial dry weight of the starting material.”

Sluiter says, “It’s a slightly different analytical procedure that approaches the process differently. And people are pointing at that as a better way.

“What the new method does is remove the ‘starch’ from the material prior to the acid hydrolysis so that only cellulose glucan is present during the reaction. This eliminates the need to quantify and mathematically correct for starch with a potentially imprecise measurement.”

Part of the reasoning for the development of an NREL analytical method was to have a transparent analytical method that can be discussed and critiqued, Sluiter says. Several labs have analytical procedures, but keep them proprietary. “This makes evaluation of the pro-

PUCK POUR: NREL researcher Alexa Schwartz inserts a sample puck into a sample reactor at NREL's Analytical Characterization Lab in the Integrated Biorefinery Research Facility. (60912.jpg)

PHOTO: DENNIS SCHROEDER/NREL

SAMPLE SORT: NREL researcher Katie Michel prepares cellulose measurement samples in NREL’s Analytical Characterization Lab. (60907.jpg)

PHOTO: DENNIS SCHROEDER/NREL

cedure very difficult,” he says. “They may be perfectly accurate, but they are a black box and will always generate doubt. A public and transparent method, such as the new NREL method, allows the critiques that improve it, such as is happening right now with discussion of the yeast body glucans.”

The reaction to his results? Sluiter isn’t certain. “My publication is new enough and is causing enough talk in the industry that I’m not sure where it will go. Right now, half a dozen major players in the area are trying to figure out what this means for them. I can’t comment on that. I literally have no idea.”

Sluiter says the goal is to get to the right number. “I don’t care if you’re using shamans to get it, as long as it gets to the right number. And we don’t have a right number right now.”

Sluiter says he wants to be helpful to the ethanol industry and hopes he can be with the new suggested NREL method. “The direction I was given was ‘Go forth and do good science.’”

Beyond Measure

The starch standard developed by NREL helps improve the cellulose measurement already, Ramm says. “We already have accuracy in measuring cellulosic production volumes.

“So the accuracy is there and I think there’s hope that a (Michael) Regan-led EPA will take a different approach to corn fiber gallons.”

Producers are required to recertify every 500,000 gallons of kernel fiber ethanol produced, a guideline designed to account for fluctuations in fiber conversions, and even crop variability, Ramm says. “There’s always been some variability. The 500,000 recertification has been used to account for variations from year to year and season to season.”

D3Max is the only fiber-to-ethanol system that produces a separate stream of cellulosic ethanol, thereby raising no concerns about measurement accuracy and exempting it from recertification every 500,000 gallons, says Mark Yancey, chief technology officer for D3Max. “We make our cellulosic ethanol in a separate ferm, put in distillation and measure what comes off that column,” he says. “It’s high enough concentration that it can be measured accurately.” The system is installed at Ace Ethanol LLC in Stanley, Wisconsin, and hasn’t been vulnerable to the EPA accuracy concerns.

But ethanol producers with in-situ corn fiber ethanol are hopeful that EPA will begin looking at applications again. Many have reapplied or are reapplying.

“They want to put a number of registration requests in front of EPA to send a signal that this is important to industry,” Ramm says. “We’re working on those registration packages so that when Regan’s EPA is looking at how they’ll move forward, at least there’s going to be a significant number of new applications.”

Bowdish says Siouxland and Elite Octane have applications pending. Elite

Jim Ramm, EcoEngineers

Octane came online in 2018, so did not apply for pathway approval under Pruitt. Siouxland, however, first applied in 2017. “Nothing ever happened with that and so, really, it was just a decision by our company that with the change in political leadership in Washington DC, we wanted to freshen up our registration package.”

EPA could update the GREET model now for all fuels, including corn starch ethanol, to reflect the actual greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction and relax costly and complex approval processes for a clearly beneficial fuel, Bowdish says. “We have an industry that today is entirely running at GHG emissions well beyond 20% reduction.” A recent Harvard study, in fact, estimates ethanol has an average GHG reduction of closer to 46%. The red tape on approvals wastes resources and people, both at plants and at EPA, Bowdish says. “There are tremendous resources that could be freed up and better put to use on other tasks.

“Looking forward to Administrator Regan’s leadership, we want to be a good partner and provide all the data to help Regan’s administration provide the marketplace with a lower GHG fuel,” he adds.

Ramm shares the frustration. “The idea is the kernel fiber feedstock that enters the front end of the plant, that fiber is like the skin on the kernel that sticks to your teeth,” Ramm says. “That fiber just passes through the plant. It even passes through a cow. Here we have this lowvalue feedstock that we can turn into really high-value ethanol, really low-carbon ethanol and also increase the protein in the feed. It’s really got tremendous ties to what the economy is calling for now: Higher-protein feed and lower- and lower-carbon ethanol.”

The economics have always been the spread between the value of D6 and D3 RINs, plus the second-generation tax credit, Bowdish says. “And so, for each plant, whether 50 or 150 MMgy, it’s millions of dollars per year. And more importantly, it’s a solution that could be lowering GHG emissions today, that policy hurdles continue to get in the way of.

“I am encouraged when I read Administrator Regan is going back to the science and has the desire and intent to let the science guide where the policy evolves,” Bowdish says. “As he’s building his team and putting staff back in place, where for the past four years, a significant reduction of EPA staff occurred, I’m hopeful that those staff members will look at the tremendous benefits of corn kernel fiber ethanol and look more toward climate change.”

Author: Lisa Gibson Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine 701.738.4920 lgibson@bbiinternational.com