54 minute read

BUSINESS BRIEFS

ENGINEERING BETTER SOLUTIONS

PIECING TOGETHER A BETTER TOMORROW WITH FQT ENGINEERING

• Plant/Process

Optimizations • Process

Engineering • Energy

Enhancement

Projects

Scan for your solution!

Your Trusted Technology Partner

©2022. All rights reserved. Fluid Quip Technologies, LLC. All trademarks are properties of their respective companies.

BUSINESS BRIEFS

PEOPLE, PARTNERSHIPS & PROJECTS

Summit Carbon Solutions announces director of carbon programs

Summit Carbon Solutions has announced that Ben Nelson has joined the company as director of carbon programs. Nelson has over 20 years of experience leading Nelson business strategy and commercial execution, including 15 years at Nutrien and its portfolio companies.

Nelson will play a critical role in Summit Carbon Solutions’ efforts to become agriculture’s premier decarbonization platform by helping growers understand and monetize their farm-level carbon impact, and supporting efforts through the value chain as global demand increases for lowcarbon products and high-quality removal credits.

“Summit Carbon Solutions is positioned to work with many stakeholders, influencing policy and practices that drive carbon removal and economic benefits across the ag supply chain,” said Nelson. “I’m excited to join the largest carbon removal project in the world. The 31 ethanol plant partners that have already committed to Summit Carbon Solutions are connected to 40 million acres of farmland across Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota.”

Alto Ingredients acquires Eagle Alcohol Co.

Alto Ingredients Inc., a leading producer of specialty alcohols and essential ingredients, has acquired Eagle Alcohol Co. LLC, a top distributor of specialty alcohols headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. The acquisition is expected to be immediately accretive and grow adjusted EBITDA by as much as $9 million annually in 2023 and beyond, including expected synergies.

Eagle specializes in break bulk distribution of specialty alcohols. The company purchases bulk alcohol from suppliers, including Alto. Then it stores, denatures, packages and resells alcohol products in smaller sizes, including tank trucks, totes and drums, that garner a premium to bulk alcohols. Eagle delivers products to customers in the beverage, food, pharma and related-process industries via its own dedicated trucking fleet and common carrier. The company generated over $35 million in revenues in 2021. Eagle is now a wholly owned subsidiary of Alto, and its former president, Dan Croghan, will remain with the company and has been named vice president of Alto and general manager of Eagle. Croghan and his team bring over 60 years of combined experience and expertise in the chemical and alcohol distribution industry.

Lincolnland becomes latest adopter of Advanced Processing Package

POET Portland completes construction on renewable CO2 addition

ICM has signed a second contract this year to install its trademarked Advanced Processing Package (APP), which will enable Lincolnland Agri-Energy to produce high-protein animal feed at its facility in Illinois.

APP includes four patented and patent-pending separation technologies: Selective Milling Technology, Fiber Separation Technology Next Gen, Feed Optimization Technology and Thin Stillage Solids Separation System.

Lincolnland has been using Selective Milling Technology to increase oil and ethanol yields since 2012. ICM will install the other APP technologies this spring, completing installation by the end of 2022.

APP mechanically separates corn into clean piles of fiber, oil, solubles, protein and enhanced protein with yeast. Lincolnland will use these feed components to produce a yeast-enriched 50% protein feed trademarked as ProtoMax, a high-energy feed referred to as Solbran, and DDGS.

Since APP allows plants to adjust the type and quantity of feed they produce, Lincolnland can customize its offerings based on market demands.

POET, the world’s largest biofuels producer, has completed construction on an addition to its Portland, Indiana, facility. This addition allows the biorefinery to capture renewable CO2, a coproduct of POET’s bioethanol production process, to be sold for commercial use.

POET’s renewable CO2 is a part of the all-natural POET Pure line of bioproducts that meets the most stringent requirements for quality and purity. According to the company, it is the highestgrade sustainable liquid carbon dioxide on the market.

“Carbon capture has proven to be not only a really exciting business opportunity for POET, but it’s great for the planet as well,” said Brad Jones, POET’s director of business development for carbon dioxide. “CO2 is already a part of the natural growing cycle of corn. The CO2 our facilities produce is reabsorbed by the upcoming corn crop, meaning no new CO2 is added to the atmosphere. So, our regenerative nt process results in a CO2 product that’s one of the most sustainable on the market.”

BIOFUELS MUST BE PART OF THE CLIMATE SOLUTION

Learn More at

GrowthEnergy.org/Environment

THE QUEST TO STOP E15’s SUMMERTIME SHUTDOWN

For years, E15 has been restricted in the summer. A Trump-era rule changed that but was legally invalidated last July, leaving the industry scrambling for another solution.

By Tom Bryan

Ten days into 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court gave notice that it would not review the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals mid2021 ruling that—starting June 1—will again prohibit year-round E15 sales across large swaths of the country. The high court’s re-

jection made it clear that a quick legal resolution to ethanol’s most vexing domestic growth challenge is off the table.

Emily Skor, CEO of Growth Energy, which led the petition, was among the first industry leaders to acknowledge that securing summertime E15 will now likely need to be accomplished through regulatory or legislative means. After the court’s rejection, she said, “Growth Energy will continue to explore all potential avenues to make unfettered access to E15 a reality.”

Brian Jennings, CEO of the American Coalition for Ethanol, says the outcome of Growth’s petition was not altogether predictable.

“It was a longshot, yes,” he says. “But just last year, the court took up the small refinery exemption decision from the 10th Circuit Court. So they had shown interest, and I don’t think they rejected this latest petition on the substance of the issue. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

Jennings says the high court’s decision to not enter the E15 fray closes the legal door for uninterrupted E15. But the rejection also gives clarity to what the industry needs to do. “Our collective efforts need to be squarely focused on the regulatory and legislative options at our disposal,” he says.

Legislative Fix

The most complete solution for regaining clearance for year-round E15 use is federal legislation. Last summer, after the appeals court struck down the Trump administration’s 2019 rule that lifted restrictions on summertime E15, bipartisan legislation was introduced in both houses of Congress that would allow retailers to sell E15 and higher ethanol blends year-round. Months later, ethanol trade groups still agree that a legislative fix to the issue remains ideal, but only if it doesn’t attract anti-biofuel meddlers that try to inject ride-along legislation that could compromise the renewable fuel standard (RFS) or the Clean Air Act.

Renewable Fuels Association President and CEO Geoff Cooper told Ethanol Producer Magazine in January that a legislative approach to resolving the E15 problem is plausible but risky. “There have been bills reintroduced in Congress that could fix this issue once and for all,” he said. “But the odds of getting that type of legislation across the finish line in the near term, without opening the door to mischief on the RFS and other priorities we care about, are low.”

Jennings agrees but says the costs of not finding a solution to the E15 issue outweigh the risks. “There is such a tremendous sense of urgency around trying to make sure we have uninterrupted access to E15 that we really can’t take a single option off the table,” he says.

Chris Bliley, Growth Energy’s senior vice president of regulatory affairs, says the most appealing thing about having Congress restore uninterrupted access to E15 is that it would be a blanket solution for the entire country. “A nationwide fix that takes care of this whole issue in one move

PRESSING FOR ANSWERS: With a summertime ban on E15 in many parts of the U.S. starting June 1, ethanol industry trade groups are pursuing potential legislative and regulatory solutions after the Supreme Court opted not to get involved with the issue in December.

would be ideal,” he says. “The legislation that’s already been introduced would resolve this for good—it would restore what EPA established in 2019.

Getting Congress to act on E15 would be “an incredibly heavy lift,” Jennings says, and it is implausible that a stand-alone bill would survive. “We’d have to find a way to hitch a ride on another piece of must-pass legislation” he says.

Jennings continues, “I agree that the cleanest way to fix this problem, once and for all, is for Congress to clarify the statute bill and make clear that any blend above E10 receives the 1-pound waiver. Then, we wouldn’t have to worry about the politics of the EPA, how the agency might interpret the Clean Air Act, or how a court might settle this. If Congress were to definitively act, it would be the cleanest and best solution. But, again, getting that done would be incredibly difficult.”

Regulatory Routes

In November, a group of governors from eight Midwest states sent letters to EPA Administrator Michael Regan seeking guidance ETHANOL PRODUCER_HALF PG AD from the agency on how to pursue a littleknown provision of the CAA that could allow states to independently allow year-round E15.

Specifically, the governors asked the EPA for clarification on Section 211(h)(5) of the CAA, which establishes that, upon request from a governor, the agency can apply volatility limitations to gasoline-ethanol blends that exclude the benefit of the 1-pound per square inch (psi) Reid vapor pressure (RVP) waiver provided to E10 by the CAA. “If approved,” the letter states, “it is our understanding that such a request would result in a volatility limitation of 9 psi for both E10 and E15 in conventional gasoline areas, thereby establishing a level playing field and allowing retailers to use the same gasoline blendstock for both blends all year long.”

The letter goes on to explain that the governors have not actually submitted the notification required, but are simply expressing interest in pursuing the approach and asking for guidance. “We would like to open a dialogue with the agency on this issue and we are respectfully requesting your guidance regarding the process for securing an exclusion from the [1-pound waiver],” they wrote.

More than 120 days later, the timeframe for action is intensifying, and EPA has not responded. Meanwhile, industry trade groups, growingly impatient with the agency’s inaction, are pressing EPA to use its legal authority to eradicate the RVP barrier straight away.

“From what I understand, EPA has still not responded to the governors,” Jennings says, adding that the request for guidance came from a bipartisan group. “Both Republicans and Democrats are asking for this, which you think would compel the Biden administration to respond.”

The governors, if and when they are told how to proceed, will likely petition the EPA to allow their state to opt out of the 1-pound waiver for E10. “Practically speaking, that would prompt refiners to supply a lower volatility blendstock for both E10 and E15, so it would be a way to avoid the waiver altogether,” Jennings says, adding that the eight governors, or an even larger consortium, could petition EPA simultaneously to prompt the agency to act. “Hypothetically, EPA would have to consider that and probably draft a proposed rule to effectively move forward with the request from

LOOKING UP: From June 2019 to July 2021, E15, often branded as Unleaded 88, was given the same 1-pound RVP waiver as E10, which is generally considered critical to growing the fuel's marketplace presence in areas of the country such as Minnesota, where retailers like Minnoco have embraced the higher blend.

PHOTO: MINNOCO those governors. There would be a comment period and eventually a final rule. It would take time, but it’s one way to do this.”

EPA Could Act Independently

The swiftest regulatory modification of E15’s summertime dilemma is for EPA to take action on its own.

In December, six national farm and biofuel organizations including Growth Energy and RFA asked EPA to enact regulations requiring lower-volatility conventional gasoline blendstock in the summer.

“We have been looking at whether EPA could simply step in and do that” Bliley says. “If EPA lowered the vapor pressure of the BOB (blendstock for oxygenated biofuel) in conventional areas— if they brought that baseline gasoline [RVP] down—it would be a national solution for all areas where E15 is blocked out in the summer.”

As it did under Trump, Jennings says, EPA could levy a new rulemaking allowing states to opt out of the RVP waiver. “In 2019, they looked at the Clean Air Act and found a way to extend the 1-pound waiver to E15,” he says. “In the same way, knowing that the court has already invalidated that option, Biden’s EPA could propose a new rule for a reduced volatility gasoline for E10 and E15 alike. EPA doesn’t have to sit on its hands and wait for petitions. The agency can act now, on its own.”

Under previous and current regulations, E15 is prohibited from retail sale from June 1 through September 15 in areas of the country where conventional gasoline is sold. In principle, this is done to prevent fuels with a 9-pound-psi RVP or greater from turning to vapor and contributing to smog. Neither E10 nor E15 meets the strict summer standard but the CAA made an exception for 10% blends over 30 years ago. E15 didn’t exist commercially at the time and, hence, was not given the same treatment. That is, until 2019, when EPA decided that E10 and E15 were similar enough for both blends to get the waiver. Two years later, the

NLB WATER JETTING SYSTEMS. BEST, MOST CONSISTENT

CLEANING SYSTEM IN THE INDUSTRY.

Superior cleaning of evaporation towers and processing systems makes a di erence – namely, better heat transfer and longer mean time between cleanings. NLB high pressure water jetting systems feature legendary long-running pumps, coupled with industry-leading Peinemann cleaning systems and wireless control technology from Terydon. The result is high-quality cleaning of ethanol processing componentry and safer cleaning operation without anyone needed inside the dome. NLB cleaning systems are also excellent for removing scale build up in process lines and boiler washdowns, all with the power of clean water.

Sales, service and rentals available at any of our eight North American branch locations.

NLBCORP.COM

_v 4 01 _0 21 d_ . | PSaleBun Corp B NL 2021 t righ py Co ©

courts ruled on the side of Big Oil, reversed the rule, and reinstated E15’s summertime restriction.

Even though the Trump administration made summertime E15 possible throughout the nation in June 2019, the industry’s effort to leverage year-round access to grow the fuel’s retail presence didn’t begin in earnest until 2020—just as Covid emerged. “And given how difficult 2020 was, I’d have to say 2021 was really the first near-normal year for uninterrupted, nationwide E15, even with the unfavorable court ruling in July,” Bliley says, explaining that the number of E15 retail stations in the U.S. was expected to grow from 2,500 to more than 10,000 by 2024 without the summertime ban in place. “But we just haven’t had an extended period of time with year-round RVP relief to see what it can really do.”

Some Markets Unaffected

With just a few months remaining for a solution to emerge, the ethanol industry is growingly resigned to the fact that 2022 may be

UNINTERRUPTED ACCESS: Six years ago, Thorntons began offering E15 at dozens of retail stations in and around Chicago, where lowvolatility reformulated gasoline is used and E15 is allowed to be sold year-round.

PHOTO: THORNTONS

a summer without E15 in many parts of the country. The ban does not affect the entire nation, however. Bliley explains that areas of the U.S. that have previously opted out of the 1-pound RVP waiver will continue to sell E15 this summer. “In metropolitan areas like New York, Chicago, Houston, Dallas and other places, you’ll continue to see E15 in the summer,” he says, explaining that populationdense areas of the country that have historically had issues with urban emissions control in warm weather months have opted out of the E10 RVP waiver and use reformulated gasoline (RFG) that has an RVP of about 7.4 pounds psi, allowing both E10 and E15 to maintain year-round RVP compliance. “But for areas like Iowa, Minnesota, the Dakotas, North Carolina, Tennessee and other parts of the country where conventional gasoline is used, E10 gets that 1-pound RVP waiver and E15 doesn’t.”

Jennings remains hopeful that an answer can be found soon. “If by some chance we are able to enact legislation between now and June, maybe that would allow for uninterrupted access to E15 in the marketplace,” he says. “I think, practically speaking, wheth-

er the EPA were to take a new regulatory approach to fix this on its own, or they were petitioned by Midwest states to take a regulatory approach, there’s a process they are going to have to follow and it’s a process that’s unlikely to be complete by June 1.”

In the meantime, Jennings says, EPA needs to be reminded that E15 is a proven fuel that is compatible with a quarter of a billion vehicles on the road. “Perhaps an argument can be made that, if there is a proposed rule and a comment period gets underway, that E15 could remain on the market,” he says. “Because this is undoubtedly going to be time consuming.”

Jennings says it is also unclear how EPA will enforce E15’s prohibition in the summer. “I really don’t know how the agency is going to enforce this,” he says. “If a solution isn’t in place by June, I’m pretty sure EPA isn’t going to send out enforcement officials to every gas station across half the country.”

Bliley agrees that it’s unlikely EPA has the ability to fully enforce E15 restrictions this summer, but also unlikely that major retailers would risk violating regulations. “The bottom line is that we need to get this resolved so there isn’t any uncertainty out there,” he says. “I think the retailers are unlikely to take any risk. They want consistency with E15, and we need to figure it out.”

Bliley says Growth Energy plans to continue pushing hard on all viable regulatory and legislative solutions. “I don’t think we can afford to ignore any possible solution,” he says. “It’s important that we get something in place that works for everyone. We appreciate what the governors are doing; we appreciate what our friends in Congress are trying to do; and we’re also going to keep pushing EPA on what they might be able to do. We’re staying active on all paths. It’s that critical.”

A Numbers Game

In addition to the industry’s E15 dilemma, its other lanes for domestic growth— E85 and mid-level blends—may be impeded in the next decade as existing flex-fuel vehicles (FFVs) age out over time while automakers, lacking incentives, produce fewer of them. The RFA recently reported that just 11 FFV models from two automakers are available this year, compared to more than 80 models from eight manufacturers half a decade ago.

Jennings says lower FFV production coupled with the reinstated summertime ban on E15, creates an extraordinary sense of urgency for marketplace action. “We need additional avenues or additional markets for our fuel,” he says. “FFV’s are very important but E15 is a top priority because virtually every car on the road today is approved to use it—97% of them.”

Despite the slowdown in FFV production, Bliley says, there are still more than 20 million E85-compatible vehicles on the road today. “FFVs are a tremendous benefit to higher blends,” he says, “but there are 245 million vehicles on the road that can use E15. That’s the thing. That’s why we’re fighting so hard get this right.”

Author: Tom Bryan Contact: editor@bbiinternational.com

WE’VE GOT YOU COVERED.

With choices from spongeblasting, hydroblasting, industrial vacuuming and more, Premium Plant Services has the right mix of maintenance options for your facility.

• Confined space rescue • Dry ice blasting • Hydroblasting • Hydro reclamation • Industrial vacuuming • Restoration • Sandblasting • Slurry blasting • Spongeblasting • Surface chemical cleaning • Tube bundle and heat exchanger cleaning

(888) 54 9-18 69 .

Hibbing, MN • Dubuque, IA • Tracy, MN Stevens Point, WI

PERFORMING UNDER PRESSURE

With a strong focus on quality and safety, a northern Minnesota-based industrial cleaning company with service locations throughout the Corn Belt has grown with, and near, ethanol producers. By Tom Bryan

Every company keeps some things close to the vest. Over a decade

of experience in ethanol plant industrial cleaning has given Premium Plant Services certain insights into fluid dynamics that give it a competitive edge. But the company’s real keys to success are no secret at all.

“We simply do our best to accommodate schedules, meet customer objectives and get the work done quickly. Repeating that over time builds trust,” says Mark Parenteau, Premium’s founder and CEO. “Our relationships with ethanol plants are successful because producers are familiar with us to the point where they don’t have to spend much time explaining what needs to be done. We know the plants, we know the people, and they know us. It’s about relationships and being familiar with the facilities we serve.”

It’s also about resources and know-how. Parenteau says Premium’s customers appreciate its deep bench of capabilities, equipment and specialized personnel. Over the past decade, the Hibbing, Minnesota-based company has grown into a true one-stop shop for not just ethanol plant hydroblasting, but all forms of industrial cleaning. Most producers shut down twice annually for this type of work— spring and fall—not just for cleaning but equipment repair, replacement and upgrades. With so much to do in less than a week, from pipefitter arrival to final cleanup, scheduling the work can be as challenging as getting it done.

“Plant managers have a lot going on before and during shutdowns,” Parenteau says. “Why worry about keeping track of multiple contractors when they can have one hydroblaster come in that knows exactly where to set up, how to stage the work and get it done efficiently and correctly? We can coordinate everything without the plant manager having to handhold or put in a lot of extra time and effort. They know we’re a good partner.”

Swift and Safe

Industrial cleaning during a scheduled shutdown is a process that largely pivots around intense use of horsepower with water and other media throughout the plant, from the facility’s distillation and evaporation vessels to its coproduct dryers and energy center. Shutting an ethanol plant down for days is costly but failing to do so can jeopardize plant performance or even result in equipment failure. Parenteau says the most capable hydroblasters are those that get jobs done swiftly and efficiently—inside of a customer’s targeted downtime—without sacrificing quality or safety.

Premium’s managers believe being responsive starts with staffing and resource management. Multiple service locations and 75-plus employees during peak seasons enable both Premium and its affiliate, Innovative Plant Solutions, to accommodate all reasonable ethanol plant scheduling requests year-round. In addition to their headquarters in Hibbing, the companies have service locations in southern Minnesota, eastern and northern Iowa, and central Wisconsin. With personnel, trucks and equipment at the ready in those locales, Premium can efficiently deploy its teams throughout the Corn Belt. Having multiple sites also makes it easier for team members to make shop runs for equipment or blasting media when needed.

“Our locations give you an idea of how connected to ethanol we are,” Parenteau says. “We cut our teeth on these plants, and we’ve learned

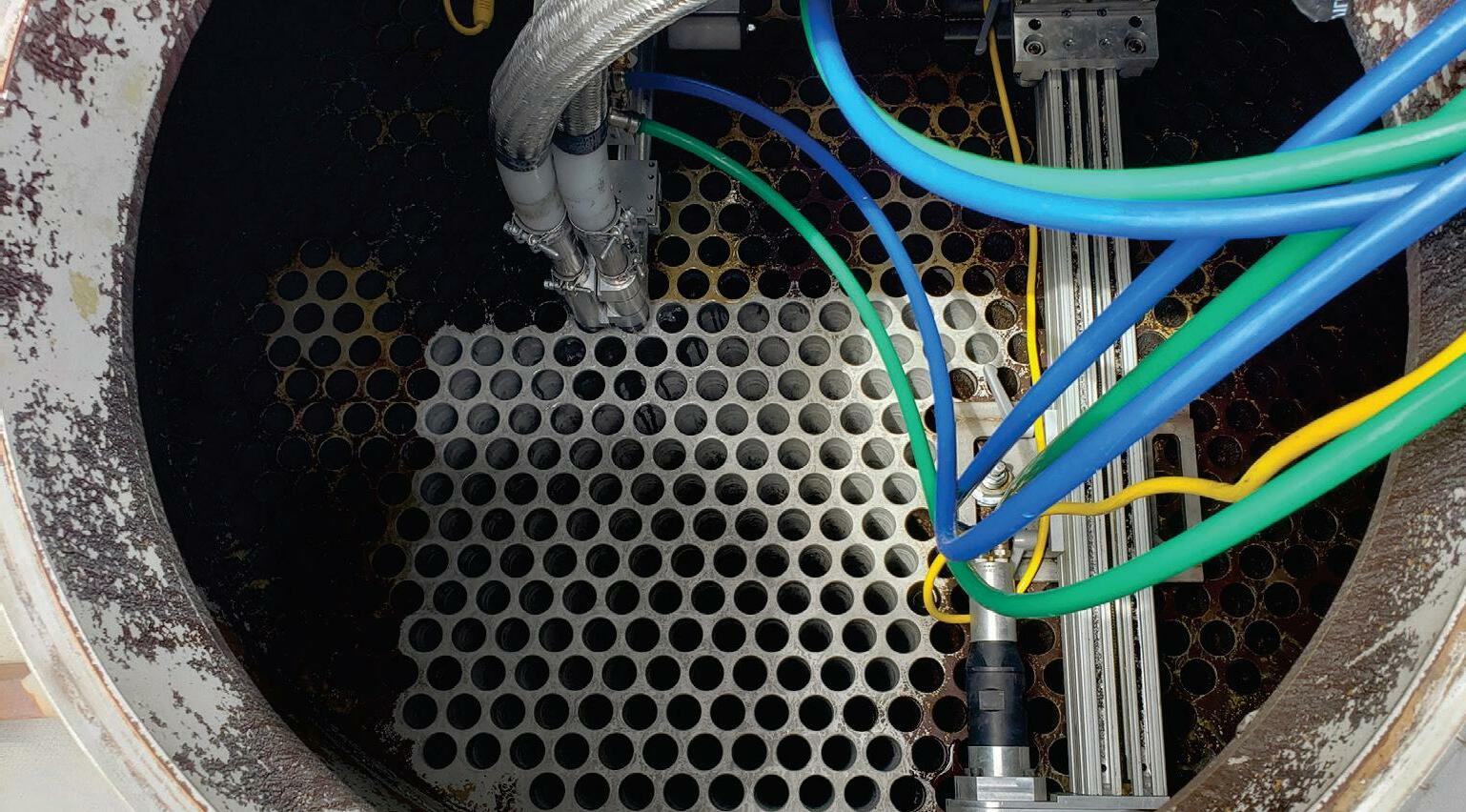

REMOTE CONTROL CLEANING: Premium Plant Services cleaning technicians are able to work via digital devices when they conduct automated lancing within an enclosed vessel.

PHOTO: PREMIUM PLANT SERVICES

how to clean them better over time in close collaboration with our customers. We have all grown together and figured this out together.” Achieving better industrial cleaning includes safer cleaning. Premium and IPS share a culture of safety rooted in communication, accountability and, to a growing degree, mechanization. “Cleaning ethanol plants, hydroblasting in particular, is among the most dangerous work in all of biofuels,” Parenteau says. “If you’re not talking to cleaning vendors right out of the chute about their culture and viewpoints on safety, you may be making a grave error. That should be your top priority.”

In addition to continuous safety training, Parenteau says Premium and IPS are progressive about adopting cleaning approaches that utilize automation to mitigate risks. “We’ve pushed hard to automate the process of cleaning evaporators, for example. You can imagine 20,000 psi on the end of a stinger two feet away, and you have to shove it down a two-inch hole that’s 30 to 40 feet long,” he says. “That kind of hydraulic pressure is very nerve-wracking and, honestly, quite dangerous. Automating that process has helped reduce a major risk element of our work.”

While the pandemic has made staffing challenging for almost all employers, Premium and IPS try to avoid the common hiring traps some contractors fall into: hiring hastily or foregoing proper training. “You really shouldn’t hire just anyone to clean ethanol plants when you’re shorthanded,” Parenteau says. “It’s not only dangerous, but you’re certainly not going to get a good quality product at the end of the day because it takes time to master the equipment. Getting in the nooks and crannies of an ethanol plant and knowing how best to get a difficult or tough spot cleaned is a real skill. Some companies simply don’t have the knowhow or patience to get it done right. We think that starts with training. You’ve got to have highly trained, qualified personnel, and that’s one of the things that sets us apart as a good hydroblasting contractor.”

Blasting Away

While there are many different forms of industrial cleaning and applicable blasting media—water, sand, slurry, dry ice and sponge—

hydroblasting and industrial vacuuming, or “vac” services, are the “meat and potatoes” of the trade.

“The physics of hydroblasting are hard to beat and, combined with vac, it’s the standard one-two punch,” says Premium’s Service Manager Dan Rice. “Hydroblasting removes the material—knocks it off the surfaces—and then its vac’d up with a powerful vacuum on a large truck, which has dump capability for appropriate disposal.”

While there is always some post-job cleanup, Rice says simultaneous blasting and vac service closely finishes each area of the plant being cleaned. “The sooner you get the process equipment cleaned and emptied of material, the sooner the facility can get back online,” he says. “You couple the two processes together as much as you can to speed things along.”

The time needed to clean a typical 50 MMgy corn ethanol plant can vary, depending on the type of facility, the way it is operated, the duration of time since its last cleaning and other factors. Rice says certain variabilities exist between, for example, ICM-designed plants

SAFER DISTANCE: A cleaning technician (left) hydroblasts an evaporator with automated lancing equipment, which greatly reduces the associated safety risks of the task. Right, a worker dumps hydroblasting debris from a truck.

PHOTO: PREMIUM PLANT SERVICES

and POET-designed facilities, requiring slightly different industrial cleaning regimens.

“The distillation and energy center cleaning processes tend to be quite different with those two designs,” he says. “Depending on what a client wants done, it could be 12 to 24 hours for an energy center in an ICM-design plant with two distillers grains dryers. And that’s typically, but not always, hydroblasting. Slurry blasting is also used. On the distillation side of the house—and this is also dependent on the design of the plant and what their situation is—it can be a 24- to 48-hour process, or even a 72-hour process, all said and done.”

Parenteau explains that the timeframe for completion can also be affected by the amount of ancillary cleaning work that is prescribed on a job. Cleaning various process lines, for example, can add additional time. As can the amount of evaporators and the severity of deposit, or foul, within the honeycombed vessels comprised of hundreds of long, narrow tubes.

“There can be anywhere from 400 to 1,600 tubes, and in the large 100-million-gallon-plus

Ethanol Handling, Handled.

AGI Tramco, a division of AGI manufactures the most complete line of chain and belt conveyors designed for safe and efficient handling of bulk materials for a variety of different industries. AGI Tramco Model GTM and Bulk FloTM are the premier bulk material conveying choices where dependable performance is needed in ethanol production environments. AGI Tramco is an ethanol industry leader and offers customizable, rugged conveying systems to producers across the globe. Contact us today for a quote: aggrowth.com/en-us/brands/tramco

plants as many as 3,000 tubes,” he says. “So, it’s hard to define the hours we spend on each plant, because there is so much variation in terms of having to punch every one of those tubes and get them perfectly spotless. And depending on the foul, it could be 30 seconds per tube or 90 seconds per tube—and we often don’t know exactly what we’re facing until we get the tops off.” Parenteau explains that his crews are accustomed to surprises and don’t get rattled by tough projects. “It’s a little like roulette, or the shuffle of the deck, when it comes to ethanol plant cleaning, because you really don’t know what you’re going to run into until you get there,” he says. “With longtime customers, you do have some understanding of the plant and how it’s typically run, but you don’t know exactly what you’re facing until you’re on site. Sometimes you quickly realize it’s going to take 30% longer just because of the more difficult material you find once you get there.”

Rice says historical knowledge of a plant and a relationship with its personnel help Premium and IPS predict and plan for each job. “There are times when our crew members even know that one of eight vessels at a plant is always tougher to clean the other seven. “In that way, we know with a fairly good margin of error what they’re walking into,” he says. “There are a lot of variables, and until you get the lid off, you have to stay prepared for anything.”

Flexibility and Trust

During the pandemic, many U.S. ethanol plants shifted their shutdown schedules or even skipped one of two annual cleanings as they

lowered their run rates, cut back on spending and tried to reduce the number of vendors on site. At the start of 2022, Parenteau says, traditional scheduling is returning.

“I would say we are very close to normal with scheduling right now, and the bookings really started to pick up last fall, extending out as far out as next spring,” he says, explaining that ethanol plants usually schedule industrial cleaning six to 12 months in advance. “Plants are definitely back on track with bookings and I’d say we are back to pre-COVID scheduling.”

Timeframes for shutdowns vary by company and region, but most producers book spring cleanings between late March and late May, and fall cleanings between early September—usually starting right after Labor Day— and mid-November.

“It can be challenging because everybody wants to get on top of those dates, so it’s pretty tough, especially if a plant had another contractor [fall through],” Parenteau says. “You never want to overschedule to the point of placing pressure on quality, standards or safety, but we have a hard time turning plants away. So we do this dance of looking at dates and trying to figure out how early or late they might be maybe willing to schedule the work.”

Parenteau says there are some things producers can do to minimize the amount of downtime required by industrial cleaning. Specifically, he says, some producers have been able to stay online while evaporators are cleaned—one vessel at a time. “The evaps are the most time-consuming part of distillation cleaning,” he says. “So if we can take those offline while you’re running, say you have eight of them and you take one down and operate with the other seven—with, of course, a little bit of a reduced capacity—you’re getting the most difficult part of the job done before shutdown. If we can get those evaps knocked out ahead of time, we can get in and out of a plant within a couple days.”

While the speed of industrial cleaning is important to producers, Parenteau says the end-result of the work is ultimately what matters most. “The quality of the cleanliness, including final cleanup, is largely what determines customer satisfaction,” he says. “Shutdown cleaning is a very big deal for ethanol plants. It costs a lot of money to have these plants shut down for days, and they’re putting a lot trust in you to get it right.”

Rice adds that building client trust starts with good communication. “With each customer, we try to demonstrate not just how the work will be done, but how it will best be done, and with what equipment, how and why,” he says. “That dialogue is shaped by our supervisor on site and directly carries over to the technicians executing the work. The people at the plant are experts on running their equipment and, likewise, we take pride in being experts on cleaning that equipment, so the facility can continue to perform optimally. That’s another part of our approach that’s no secret.”

Author: Tom Bryan Contact: editor@bbiinternational.com

PROPERTY REINCARNATIONS

Corn stover ethanol production still holds great promise. But at least two of the former ‘big three’ assets in the space have been repurposed for different forms of biofuel production. By Katie Schroeder Introduction by Tom Bryan

A decade has passed since an immense surge of interest in cellulosic ethanol production swept through the Corn Belt, leading big-name companies down a path of daring research, investment and construction that collectively amounted to over a billion dollars of unrealized or deferred success.

Nationwide, nearly a dozen advanced ethanol projects emerged during cellulosic’s peak period of activity from about 2010 to 2015—different places, different tech, different feedstocks—but few operated as planned and many simply didn’t get done. The largest and most celebrated of the domestic efforts, a trio of competitors known as the “big three,” were Abengoa, DuPont and a joint venture between POET and Royal DSM called Project Liberty, which still remains. Each of the three companies set out to convert corn stover—the plant’s stalk and leaves rather than its kernel—into high-value, D3 RIN-earning cellulosic ethanol. Abengoa built its plant in southwest Kansas while DuPont and POET-DSM sited their facilities in central and northern Iowa, respectively. Construction on the landmark biorefineries— ranging from 20 to 30 MMgy—crested by late 2013 and all three sites were substantially complete by late 2014 or early 2015. While the plants were completed and in commissioning, fanfare ensued at grand openings that included high-profile CEOs, big-name politicians and even royalty, but none of the facilities performed as planned and, within three years, two of the three plants were shuttered and sold.

Today, only Project Liberty in Emmetsburg, Iowa, remains intact, albeit not in commercial operation. The other two facilities have new ownership, bevvies of new equipment and infrastructure on site, and vital new purpose. Here’s what’s become of cellulosic ethanol’s big three since they boldly broke ground, built and inspired an industry to think big a decade ago.

Renewable Diesel in Hugoton

In Hugoton, Kansas, sits a former cellulosic ethanol plant with a storied history. Initially created as part of an effort by Spainbased Abengoa to produce cellulosic ethanol, the plant is now being used for a different purpose—renewable diesel production—after twice changing hands in the past seven years.

After Abengoa laid off its Hugoton employees under financial difficulties in 2015, the refinery went into bankruptcy and was acquired by Synata Bio Inc. for $48.5 million a year later. The plant changed ownership again in early 2019 when Seaboard Energy (formerly High Plains Bioenergy) bought the facility from Synata for an undisclosed amount.

Seaboard Energy is one of several businesses under the Seaboard Corp. umbrella. Seaboard Energy President and CEO Gary Louis describes the parent corporation as a diversified agricultural and shipping company, but its connections to pork and chicken processing—the corporation owns Butterball—give context to its biofuel connections.

Louis says Seaboard decided to acquire the Hugoton plant from Synata due to the site’s existing base infrastructure, including electrical service, gas, rail, warehousing, control rooms, freshwater supply, wastewater treatment and almost 800 acres of land. In addition to attractive infrastructure, the site’s proximity to animal waste feedstocks, some

DUAL-FUEL COMPLEX: Instead of producing cellulosic ethanol in Nevada, Iowa, Verbio is making renewable natural gas (RNG) from corn straw and, soon, conventional ethanol from corn at the former DuPont site. Some of the RNG produced there will be used to fire the ethanol plant’s boilers.

PHOTO: VERBIO

sourced from Seaboard’s own assets in the area, made the investment appealing.

“It is in an ideal location for animal fats,” Louis says. “There’s a lot of beef and pork processing in the area. It is 40 miles from our pork processing plant in Guymon, Oklahoma. It is on the Cimarron Rail which feeds the BNSF Railroad, and the biggest reason we wanted to do renewable diesel was because it is a drop-in fuel and has allowed us to expand our marketing opportunities

FEEDSTOCK FIT: Seaboard Energy is the current owner of the former Abengoa complex in Hugoton, Kansas (pictured here post original construction in 2014). Seaboard has repurposed the site for renewable diesel production. The facility will utilize animal waste feedstock, some of which will be sourced from Seaboard’s own food processing plants.

BIOFUEL MAKEOVER: After Abengoa ended its cellulosic ethanol run in Hugoton, Kansas (shown here during commissioning in 2015), the facility was acquired by Synata Bio Inc. in 2016. A few years later, Seaboard Energy acquired the complex and built an 85 MMgy renewable diesel plant on the same footprint.

PHOTO: ABENGOA

for our liquid renewable fuels business. It will also allow us to blend our biodiesel into a blended renewable fuel.”

Seaboard currently owns and operates two biodiesel plants: one in Guymon and one in Saint Joseph, Missouri. The company has been part of the liquid renewable fuels industry since it started producing biodiesel through toll processing it with their animal fats, first in Guymon, starting in 2008, and later in Saint Joseph, starting in 2016. The Hugoton plant will be the first to produce renewable diesel with a nameplate capacity of 85 MMgy, considerably more volume than the 25 MMgy cellulosic ethanol plant that stood there previously. The plant is not yet operational and still in commissioning, according to Louis.

Seaboard was able to utilize support infrastructure on site, but the new plant’s feedstock pretreatment units, hydrogen plant and renewable diesel processing units were built new. “The primary process facilities required to convert fats and oils into renewable diesel were constructed as greenfield projects,” Louis explains. “A lot of people think we went in and changed the process to make renewable diesel, we did not, we went in and used the existing infrastructure to support a greenfield renewable diesel plant.”

Emmetsburg Being Used for R&D

In many ways, ethanol giant POET and Dutch company Royal DSM led the push to create cellulosic ethanol from corn stover. Together, they created the 20 MMgy Project

Liberty, which came online in September 2014 in Emmetsburg.

The plant successfully converted corn stover, more specifically corn cobs, leaves, husks and stalks, and even sold cellulosic ethanol from the plant into the market, despite having to overcome bottlenecks in feedstock pretreatment.

POET-DSM decided to pause production in 2019, citing changes in the renewable fuel standard that negatively impacted the market demand for cellulosic ethanol. Specifically, company officials said, EPA manipulated RIN prices, continuously set renewable volume obligation (RVO) levels lower than they should have been, blocked new cellulosic pathways and granted undeserving small refinery exemptions. “The EPA has effectively cut the incentive to blend cellulosic biofuel from nearly $3 to as low as 59 cents per the D3 RIN value,” the company stated in late 2019.

Frustrated with the EPA’s management of the RFS, the company announced that Project Liberty would shift away from cellulosic ethanol to focus primarily on research and development, with the goal of improving mechanical reliability and creating additional technological efficiencies. As part of the

READY AND WAITING: Frustrated with the EPA’s management of the renewable fuel standard (RFS), POET-DSM put its cellulosic ethanol facility on hold in 2019, announcing that the completed 20 MMgy biorefinery (shown here in 2016) would be used for R&D until regulatory oversight of the RFS improved.

PHOTO: POET

BIOGAS BY THE BALE: The bales of straw next to this vehicle can be made into enough renewable natural gas (RNG) to run it for nearly 8,000 miles. After its current expansion is complete, Verbio will have the capacity to convert 100,000 metric tons of corn straw into RNG.

PHOTO: VERBIO

effort, POET-DSM said the facility would use biomass stored on site, or already under contract, and would cease purchasing additional baled stover. Since ceasing commercial operation, POET has not disclosed how the idled facility is being utilized and maintained, but has previously indicated that resuming production is possible.

RNG Production in Nevada, Iowa

The third of the Big Three corn stover ethanol plants to be completed was built by DuPont in Nevada, Iowa. The plant had its grand opening in October 2015 but was still in the commissioning process in mid-2017. It had the capacity to produce 30 MMgy of cellulosic ethanol at full capacity, however DuPont decided to exit cellulosic fuel and sold the plant to Verbio North America Holdings in 2018, having never reached real operability. Instead of producing cellulosic ethanol, Verbio plans to produce renewable natural gas (RNG) and corn-based ethanol at the location. The plant’s RNG production began in December 2021, initially producing an RNG volume that is equivalent to 7

WE MOVE THE WORLD FORWARD.

RAIL, STORAGE AND MARINE CAPABILITIES

RAIL • UP and BNSF direct access • 160 railcar unloading spots, unload at 15,000 bph • Landing tracks capable of staging 4 unit trains • Unit train turn times of 24 hrs or less STORAGE • 2 million barrels of dedicated storage • Denaturant & bitrix blending • Foreign Trade Zone MARINE • 3 deep draft berths • Loading rate of 10,000 to 20,000 bph • 3 barge berths

ADDING NEW PIECES: The former DuPont cellulosic ethanol plant (shown above, pre-acquisition) left its current owner, Verbio North America, with plenty of useful infrastructure for RNG and corn ethanol production. To the right, Verbio CEO Claus Sauter (left) walks the grounds with a board member and a plant employee.

PHOTO (ABOVE): DUPONT PHOTO (RIGHT): VERBIO

MMgy of ethanol. After an expansion that is already underway, the company will have the capacity to convert 100,000 metric tons of corn straw into RNG. And by the end of 2022, Verbio plans to expand the biorefinery further with the introduction of ethanol production integrated with biogas.

Greg Northrup, president of Verbio North America, explains that the biorefinery will integrate the ethanol and RNG production processes in Phase II. They plan to produce 60 MMgy of corn-based ethanol starting in October. The stillage left over from producing ethanol will be used to make an additional 12 million ethanol gallons equivalent of RNG, bringing their total to 19 million EGE.

“We end up with better synergy, better economics, better design and operating capabilities because we are integrating the two operations together; it makes us much more sustainable ultimately,” Northrup said.

Greg Faith, president and general manager of Verbio Nevada LLC, describes what this sustainability looks like in day-to-day operations. “Where they integrate really nicely is the energy we make from some of the renewable natural gas we make can be used to heat our boilers,” he says, adding that the use of biogas allows the plant to have a much lower carbon intensity score.

Significant infrastructure changes were made to the plant during its transition. Eighty percent of the plant now has newly

When what’s inside gets out.

Ramsdell’s got you covered. Our secondary containment systems have been protecting valuable tank contents—and the environment—since 1988. From storage tanks to railcars, when what’s inside gets out, you have one chance to capture it.

constructed assets, however, Verbio was able to use 20% of the existing assets to produce corn-based ethanol. Faith explains that anerobic digestion and gas cleaning were two of the main assets which needed to be added to produce RNG. Although Verbio could not utilize all the cellulosic ethanol equipment, they were drawn to the Nevada plant for other reasons.

“What is more important about the site for us is … we sit right on top of a natural gas pipeline that’s operated by Alliant Energy,” Northrup says. “If we’re producing renewable natural gas, access to the interstate pipeline gas supply system is critical. And so, with the pipeline being right at our front door it [is] a truly important asset for us as it relates to infrastructure.”

He continues, “The other thing that was beneficial to us along with everything else, there is a 25-megawatt substation that was already part of the construction process. We use a lot of power, and so that was an investment that we didn’t have to make because of the purchase.”

The Nevada biorefinery is the first industrial-scale RNG facility of its kind in the United States. Faith explains that the technology of converting corn stover into RNG is a proven technology developed by Verbio in Germany over the last ten years. “I think that’s the exciting part; this is a new market in the United States and a proven technology,” he says.

“We’re very fortunate,” Northrup agrees. “The technology and operating capabilities we have are just very exciting and we’re happy to bring that to the U.S. We’re looking forward to really great growth here and increasing employment as part of the process and helping growers with another revenue stream for their agricultural residue.”

The biorefinery will utilize 75,000 to 100,000 tons of corn stover in the first phase of the RNG production process. Northrop explained that the Nevada plant’s location in the middle of the Corn Belt was crucial for access to the feedstock needed for RNG production.

Faith explains that they work to not strip the soil of its nutrients when removing crop residue for use as feedstock. They address this issue by applying humus fertilizer produced at the biorefinery.

“It’s really up to the farmer, because some of our farmers to the north would rather we take it and not give the humus back,” Faith says. “Because north of us we have quite a few pig farmers that would choose to put manure on their ground, so it depends.” Faith says Verbio and Iowa State University are actively talking to area farmers about the benefits of removing some of their corn stover from their fields and reapplying nutrients.

Reliability from the government is important to the biofuels industry to be able to make good investments, Northrup explains. “When I spend millions of dollars on a facility as I’ve done in Nevada, I don’t make those decisions lightly and I expect a fair return on that investment [while] we’re trying to help the United States maintain energy independence with renewable fuels as part of the mix,” he says. “So, to be successful doing that, these are long-term projects that require long-term commitment, and we need a government that gives us long-term predictability in the standards that we’re trying to achieve.” The cellulosic ethanol industry was hampered by technology issues, Northrup says. However, he believes that the ethanol industry—and to a lesser extent the RNG industry—need predictability from Washington to thrive.

“We need consistent, reliable predictions of what can we expect as an industry from Washington,” he says. “We haven’t had that the last four to five years, unfortunately.”

Author: Katie Schroeder Contact: katie.schroeder@bbiinternational.com

REASONS TO UPGRADE: While more expensive than conventional disc-stack technology, Flottweg Tricanters have several advantages. They are easier to maintain and operate and can significantly improve distillers corn oil yield.

PHOTO: FLOTTWEG

The Benefits of Using a Tricanter for Corn Oil Recovery

A case study of a multi-facility ethanol company’s successful incorporation of Tricanters into its production portfolio. By Bill Griffiths

With four South Dakota facilities recovering corn oil, Glacial Lakes Energy LLC was faced with the challenge of selecting the primary separation technology for one of its

plants. The company chose a Tricanter over its familiar disc-stack technology for the Aberdeen facility and doubled corn oil production the day it began operating. Even though the Tricanter machine is more expensive, GLE Director of Operations Pat Hogan said the additional cost was justified because of its ease of operation, higher yield, lower maintenance, increased uptime and cleaner oil.

Glacial Lakes Energy has four facilities in operation in South Dakota—Aberdeen, Huron, Mina, and Watertown—all overseen by Hogan, who is based in Watertown. All four facilities are located within a twohour driving radius. Each plant has its own plant manager, production manager and maintenance manager responsible for taking care of and running their equipment.

CONTRIBUTION: The claims and statements made in this article belong exclusively to the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ethanol Producer Magazine or its advertisers. All questions pertaining to this article should be directed to the author(s).

Glacial Lakes Corn Processors (GLCP), was formed in 2001 as a South Dakota Cooperative comprised of more than 4,100 shareholders. GLCP owns 100% of GLE and its four ethanol plants.

GLE-Watertown, an original 40 MMgy nameplate facility, became operational in August 2002. In 2007, the facility was expanded and currently produces more than 130 MMgy of ethanol. GLE-Mina became operational in June 2008 as a 110 MMgy facility, and is now operating at 140-plus MMgy. In December 2019, GLE purchased two additional ethanol production facilities located in Aberdeen and Huron, South Dakota. The Aberdeen plant currently produces about 50 MMgy. The Huron plant currently produces about 40 MMgy.

Combined, GLE’s ethanol plants purchase more than 125 million bushels of corn per year, and produce 360-plus MMgy of ethanol; 918,000 tons of feed products/ distillers grains and 51,000 tons of corn oil per year.

The Challenge and Solution

GLE was previously using a disc-stack separator at Aberdeen for oil recovery and separation. Because the machine was simply too small and not producing at an acceptable rate of recovery with low oil yields, Hogan was convinced the production could be stronger with upgraded equipment.

“This presented us with the opportunity to either install more disc-stack units, or upgrade to a different technology,” Hogan said, explaining that the choices were a Flottweg Tricanter, or more disc-stack separators from another supplier.

“From a straight oil-separation perspective, both are good technologies,” Hogan said. “If you have oil to pull out of a stream, they will both pull it out equally and as efficiently. However, I lean heavily toward the Tricanter for corn oil ethanol recovery.”

Hogan chose the Tricanter for the Aberdeen plant, but continues to use the disc-stacks for two of the other GLE facilities. The size of each facility is a determining factor for selecting technology and the number of units needed, Hogan said. • The Mina plant (140+ MMgy) is using two Tricanters. • The Watertown plant (130 MMgy) is using three disc-stacks. • The Aberdeen plant (50+ MMgy) is using one Tricanter. • The Huron plant (40 MMgy) is using one disc-stack.

Even though the Tricanter is initially more expensive, sometimes by as much as 30-40%, Hogan said there are five reasons why he prefers the Tricanter over the discstack technology for corn oil recovery: 1. Ease of operation, 2. More yield with regard to production uptime, 3. Lower maintenance, 4. Less downtime, and 5. The Tricanter produces cleaner oil than disc stacks.

“The number one reason that I chose the Tricanter is because I believe it is easier to operate,” Hogan said. “All the plants already have similar types of horizontal bowl decanters. In addition to the ease of operation, the Tricanter is less finicky than a disc-stack, which basically means that on a daily, weekly and monthly basis, Tricanters require much less maintenance. If you take care of the machine, it only requires an annual rebuild. The disc-stack machines require quarterly rebuilds in addition to the annual rebuilds.”

Hogan noted that the Tricanter requires a weekly or bi-weekly cleaning, which equates to taking it out of service for 4 or 5 hours for cleaning, while the disc-stack machines need multiple water flushes daily in addition to weekly cleanings.

The annual maintenance costs for the disc-stack and Tricanters are relatively similar, with the Tricanter being marginally less expensive. But the Tricanter provides more uptime, according to Hogan, and is more forgiving during operations.

“For example, we feed these machines syrup which is pulled from our evaporators, and if you perform hydroblasting or CIP on your evaporators, the disc-stacks must be taken offline for a few hours during this procedure to prevent disc blockage,” Hogan explained. “However, the Tricanter will just gobble that up, and you can keep it running. This provides more uptime and more production.”

According to Hogan, the five benefits justify the additional cost incurred to purchase the Tricanter technology.

“Now, we have some really good folks who take care of the disc-stacks in our two facilities, and they tend to make it look easy. But I’ve been in plants that were perhaps not as technically savvy, and I’ve seen how those disc stacks can create a lot of headaches if you don’t pay them 100 percent attention,” Hogan explained. “The Tricanter is just a lot more forgiving. There are fewer mechanical moving parts, whereas with the disc-stack there are a lot more little things that can go wrong with them.”

When Hogan began working with GLE, there were two facilities—Mina and Watertown—and each of them were using two disc-stack machines. Mina was in a similar position as Aberdeen in early 2021—the disc-stacks were not making very good oil and had low oil yield.

“We had to make a choice to upgrade the system,” Hogan said. “At the time we considered whether to buy a couple more disc-stacks to increase their capacity or replace the disc-stacks with a Tricanter. We opted for two Tricanters. We doubled the oil yield as soon as we turned on the Tricanter.”

Since the two-disc stack machines were still operational, Hogan said they decided to leave one in Mina as a backup unit to use during weekly Tricanter CIP procedures. The second disc stack machine was installed in Watertown, a facility that now runs three disc-stacks, markedly improving their oil production with the increased capacity. In 2019, the Huron and Aberdeen plants were purchased by GLE. Huron already had a disc-stack that was sufficient for that plant, so it wasn’t upgraded or replaced. The Aberdeen unit, however, did not have enough capacity to support the plant, so one Tricanter was installed to replace it.

How the Tricanter Works

This three-phase centrifuge separates the maximum amount of distillers corn oil from syrup for added revenue. The Flottweg Tricanter features simple opera-

PLANT UPTIME IS IMPORTANT TO EVERYONE

Our full service team of experts have 20 years of ethanol plant maintenance rewliability and uptime history. 24/7 support and ready access to a full inventory and all Fluid Quip equipment parts, ensures that you maintain your plant’s uptime status.

• OEM Parts Warehouse • $1 million+ on-hand inventory • Fully stocked trucks • Overnight/hot shot shipping

PARTS

EQUIPMENT SERVICE

• Factory Trained & Certified • MSC™ Systems • SGT™ Grind Systems • FBP™ Fiber By-Pass

Systems • MZSA™ Screens • Paddle Screens • Grind Mills • Centrifuges DIALING IN ON QUALITY: With an adjustable impeller, the Tricanter’s light phase separation and discharge can be precisely set while the machine is running to get the highest possible oil purity. This can be done manually or automatically with a Flottweg control system.

PHOTO: FLOTTWEG

tion for cleaner oil and more uptime compared with standard separators. The high oil yield provides a rapid return on investment.

The Flottweg Tricanter reduces solids debris and fatty acid content to produce cleaner recovered oil that can be sold as a feed ingredient or biodiesel feedstock that can earn a premium price over other forms of oil.

Even when you sell non-food grade corn oil as a separate, higher-value product, the fat content in the DDGS remains above 8.5% and delivers an average profat content in excess of 35%.

Classic bioethanol plants produce ethanol, solids (DDGS), and the residual syrup, created from evaporating and drying the thin stillage. However, modern, innovative plant operators utilize an additional option for raw material extract. After passing through the decanter, the thin stillage is mainly free of larger solids (still containing fines), but not from valuable oil. For example, to separate corn oil in corn-based ethanol plants, Tricanters are commonly used.

The structure and function of the Tricanter are similar to those of a decanter (two-phase separation). The decisive difference between these two machines is in the way that the liquid is discharged. A Tricanter uses two liquid phases: a “heavy” liquid phase (higher density and discharged under pressure) and a “light” liquid phase (lower density and discharged without pressure). This is the principle used to separate oils from the thin stillage to yield yet another raw material that can be used, for example, to manufacture biodiesel.

An adjustable impeller sets the separation between the light phases. This is traditionally done by a static weir plate. With an adjustable impeller, the light phases can be precisely set while the machine is running to get the best possible oil quality. This can be done manually or automatically with a Flottweg control system.

The Tricanter offers many advantages for corn oil recovery: • Combining the processing steps eliminates the need for additional separation stages, which results in considerable cost savings. • In addition to its high selectivity, the Tricanter is versatile. It can adapt to changing inlet conditions at any time. • It offers the highest possible phase separation and unparalleled flexibility due to the adjustable impeller. • Maintenance is similar to that of the decanter.

Results for Glacial Lakes Energy

Hogan said he prefers the Tricanter technology in all cases for corn oil recovery, although sometimes the cost is not justified. “If the Huron unit had a catastrophic failure, for example, I would replace it with a Tricanter,” he said. “But for now, the extra expense can’t be justified.”

The newest installation in Aberdeen is already producing significant improvements in yield. Previously, the plant was producing approximately 0.55 pounds of corn oil per bushel of corn. “As soon as we turned the Tricanter on—day one—production improved to .81 pounds,” he said. “This clearly demonstrates the improvement in capacity.”

For now, GLE will continue to use the current technology in place in its four South Dakota plants. “The disc-stacks are reliable, so the chance of a catastrophic failure is fairly low,” Hogan said. “But this is a good solution for our Aberdeen plant.”

And for Hogan, the additional cost of the equipment is clearly justified with the ease of operation, low maintenance, higher yield, less downtime and cleaner oil.

“I’m asked this question all the time when I put in a capital request for a Tricanter—the board will inevitably ask why I prefer the Tricanter over the disc-stack, particularly with the difference in purchase price,” Hogan explained. “I go through this whole scenario of explanations each time. Honestly, sometimes it just comes down to personal preference. I’m sure there are some people in the industry who would prefer the disc-stack technology. For me, I’ve run these Tricanters at four different facilities and they just run. You install them, take care of them, and they just run. For me, that’s the most important thing. It’s that simple.”

Author: Bill Griffiths Head of Sales – Edible Fats & Oils Flottweg Separation Technology bgriffiths@flottweg.net