Student Edition

Unit Opener

Geography Challenge 1 Inquiry Project 4

Lesson 1

Investigating the Past Through Inquiry 6

How do social scientists interpret the past?

Lesson 2

Themes of World History 24

What are the themes of world history?

Lesson 3

Early Hominins 36

What capabilities helped hominins survive?

Lesson 4

From Hunters and Gatherers to Farmers 4 6

How did the development of agriculture change daily life in the Neolithic Age?

Unit Closer

Studying Sources 5 4 Timeline

unit 2

Unit Opener

Geography Challenge 60 Inquiry Project 6 4

Lesson 5

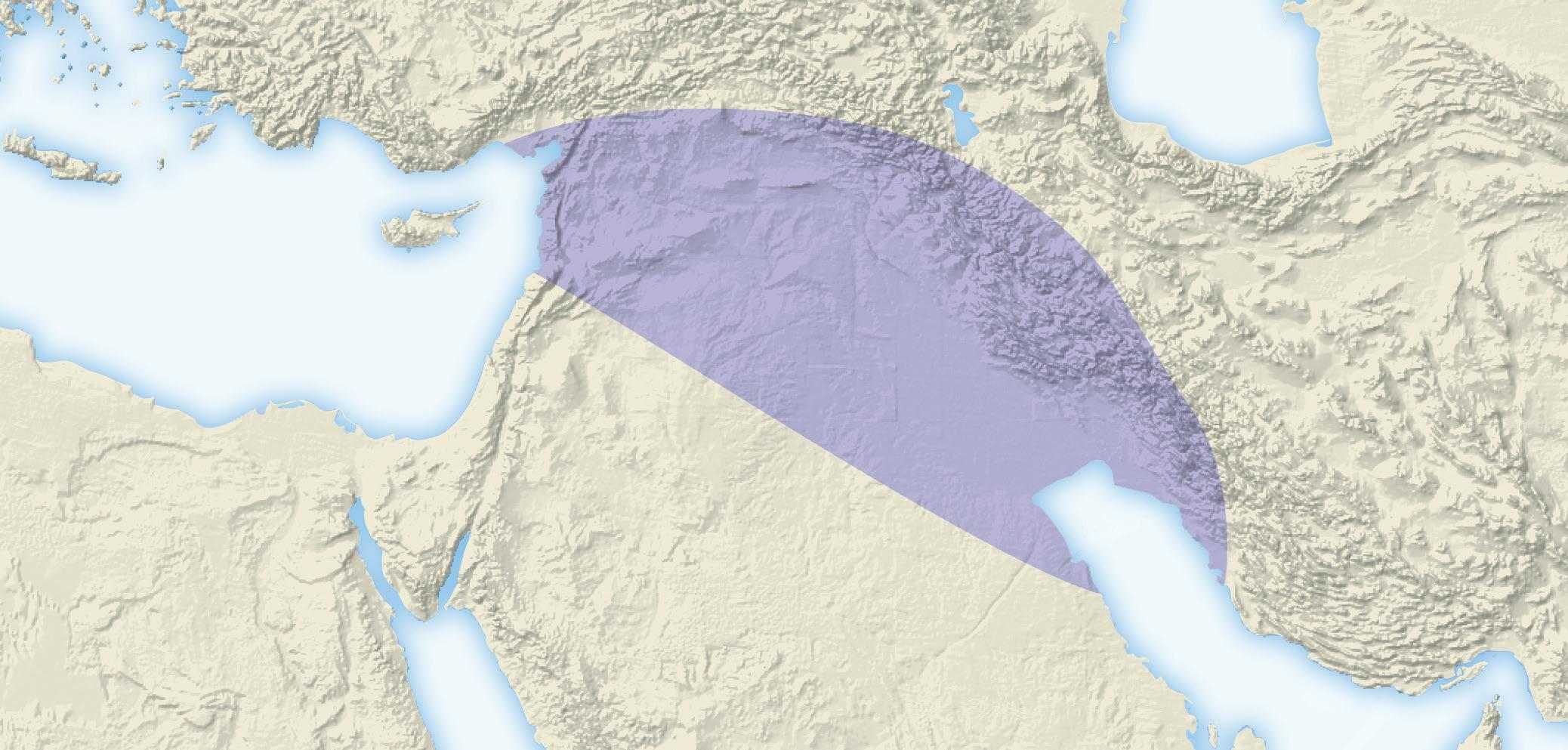

The Rise of Sumerian City-States 6 6

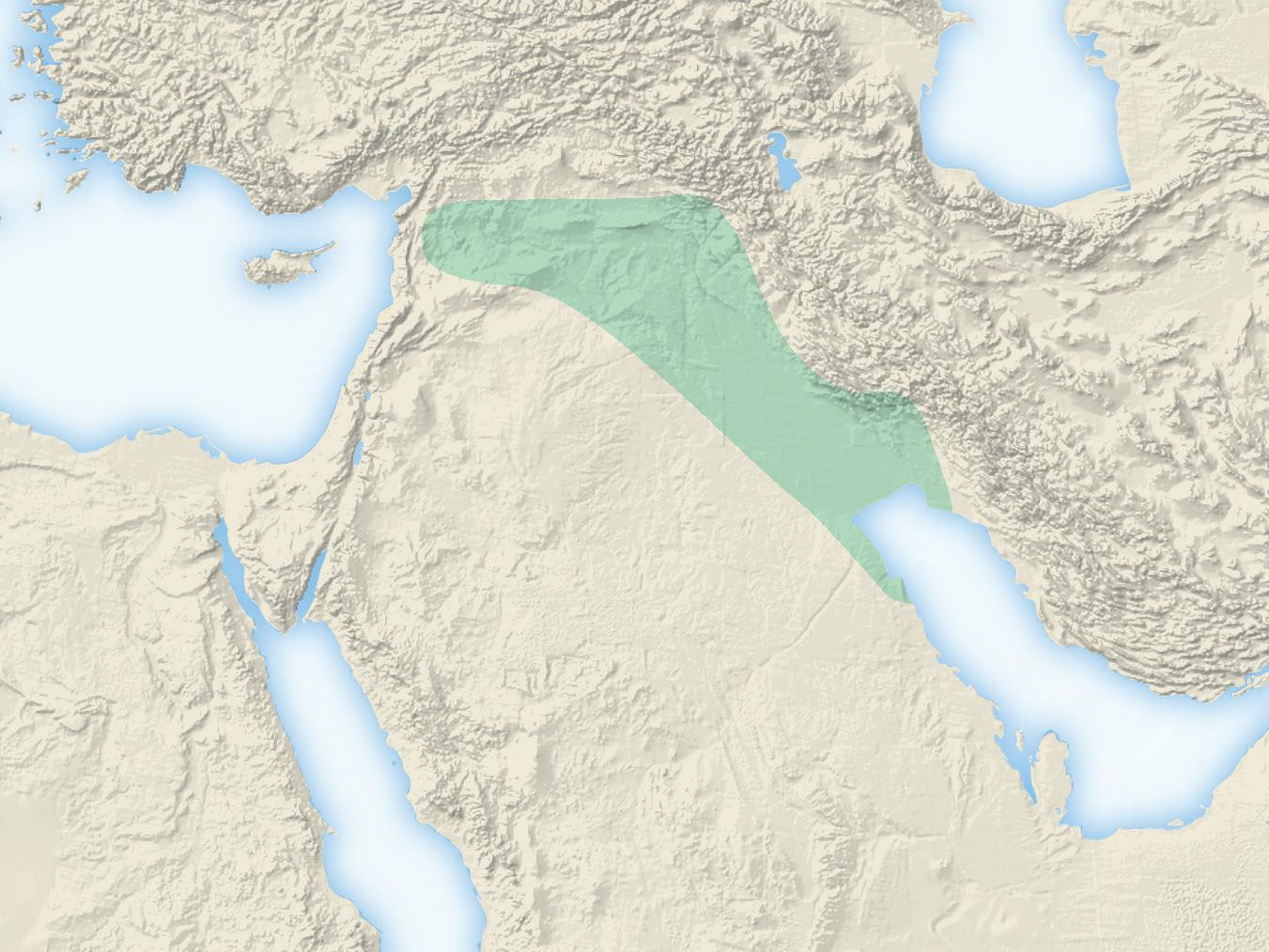

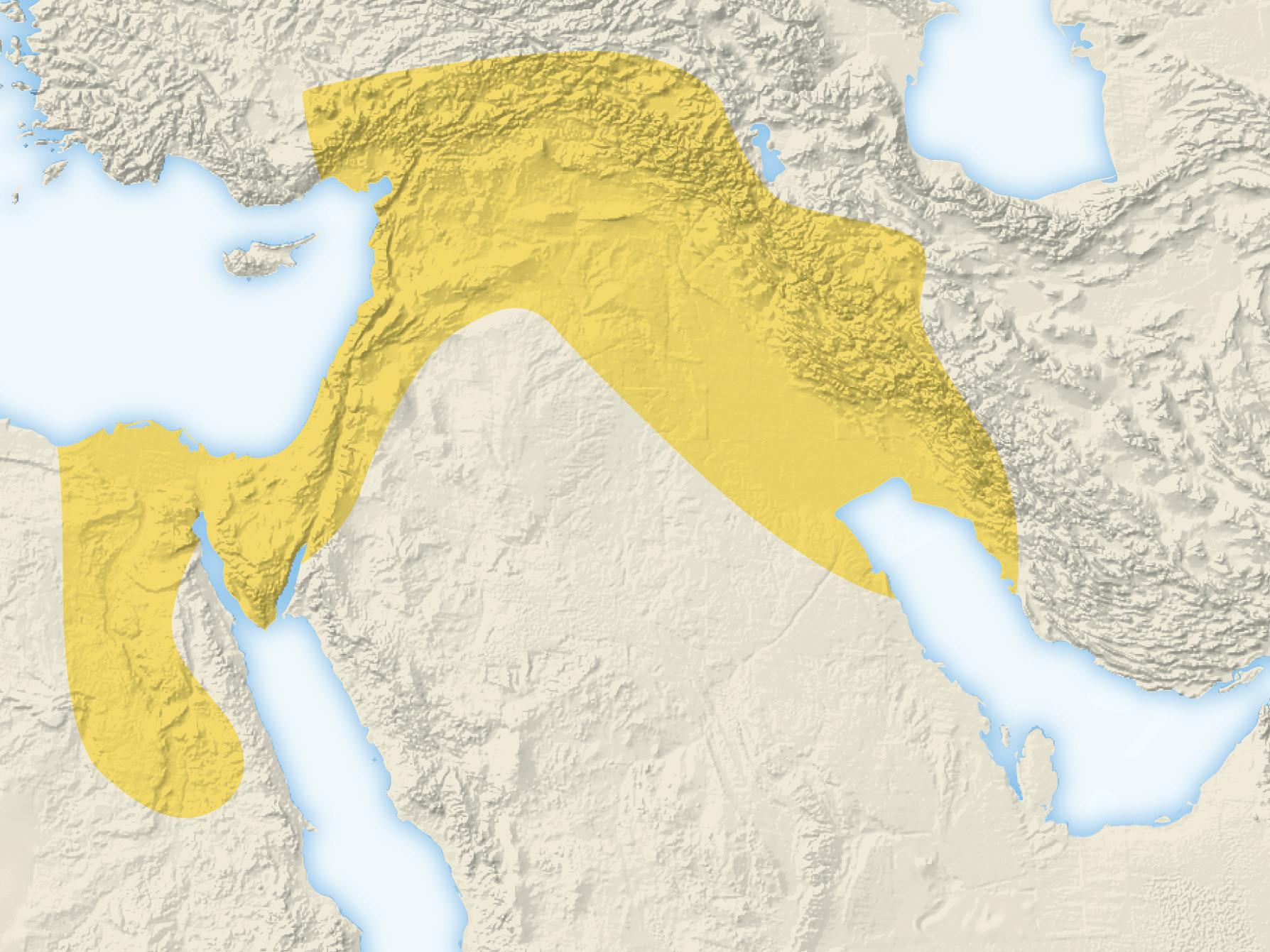

How did geographic challenges lead to the rise of city-states in Mesopotamia?

Exploring Biographies – Detecting the Past: Clues from Archaeology

Lesson 6

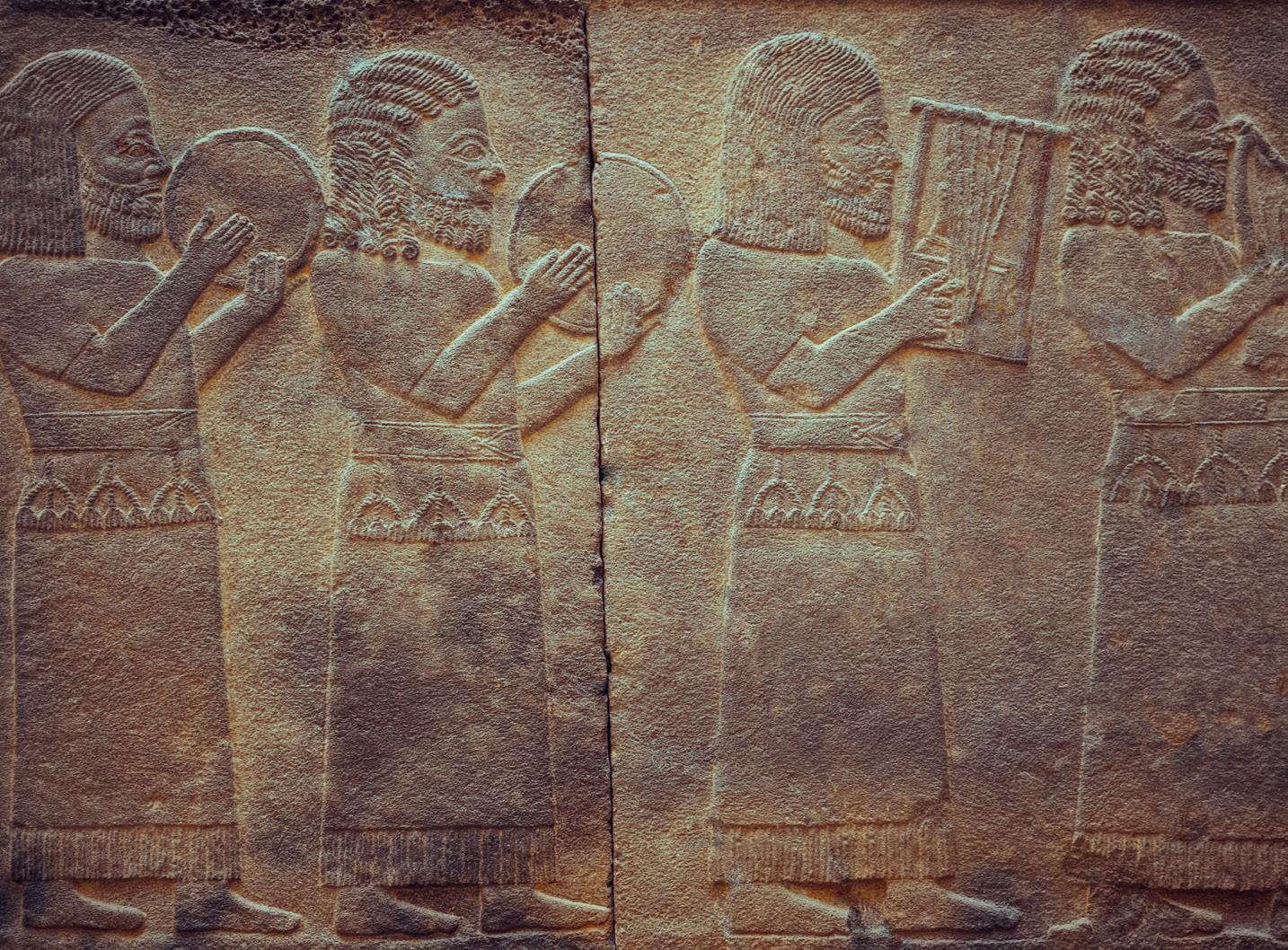

Ancient Sumer 78

Why do historians classify ancient Sumer as a civilization?

Investigating Primary Sources – How Did the Different Social Classes of Sumer Interact with One Another?

Lesson 7

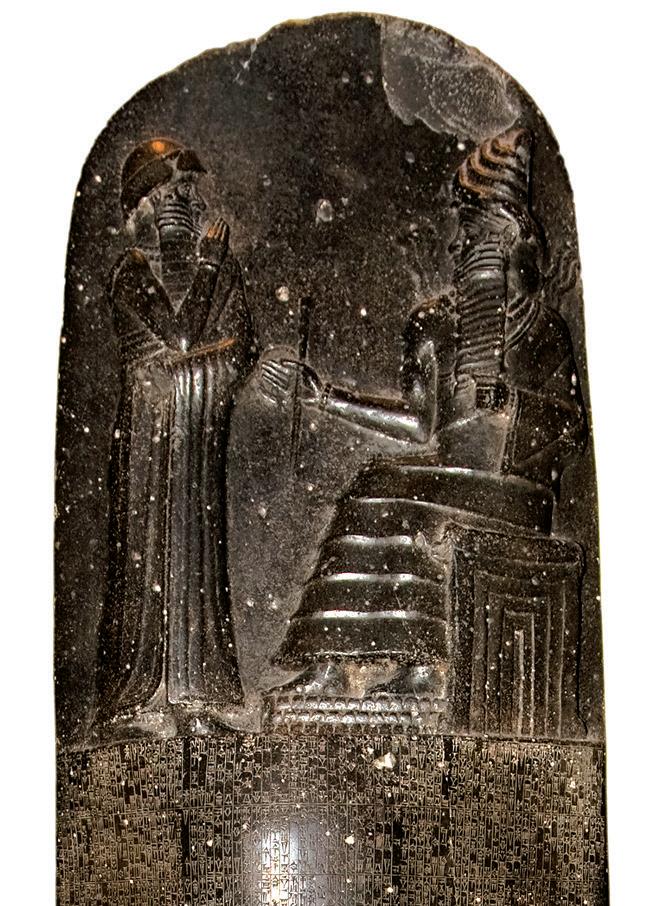

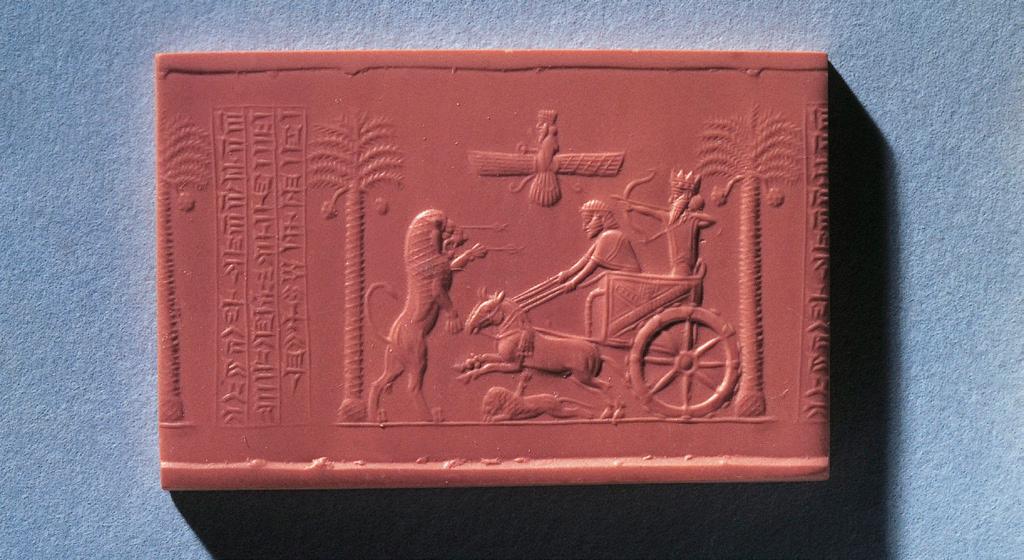

Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia 92

What were the most important achievements of the Mesopotamian empires?

Lesson 8

Ancient Persia and Its Context 102

What can we know about ancient Persia?

Lesson 9

The Achievements of Ancient Persia 122

In what ways did ancient Persians influence the world around them?

Lesson 10

Early Civilizations in the Americas 148

What do we know about the ancient civilizations in the Americas?

Unit Closer

Studying Sources 164 Timeline Challenge 168

Geography Challenge 170 Inquiry Project 174

Lesson 11

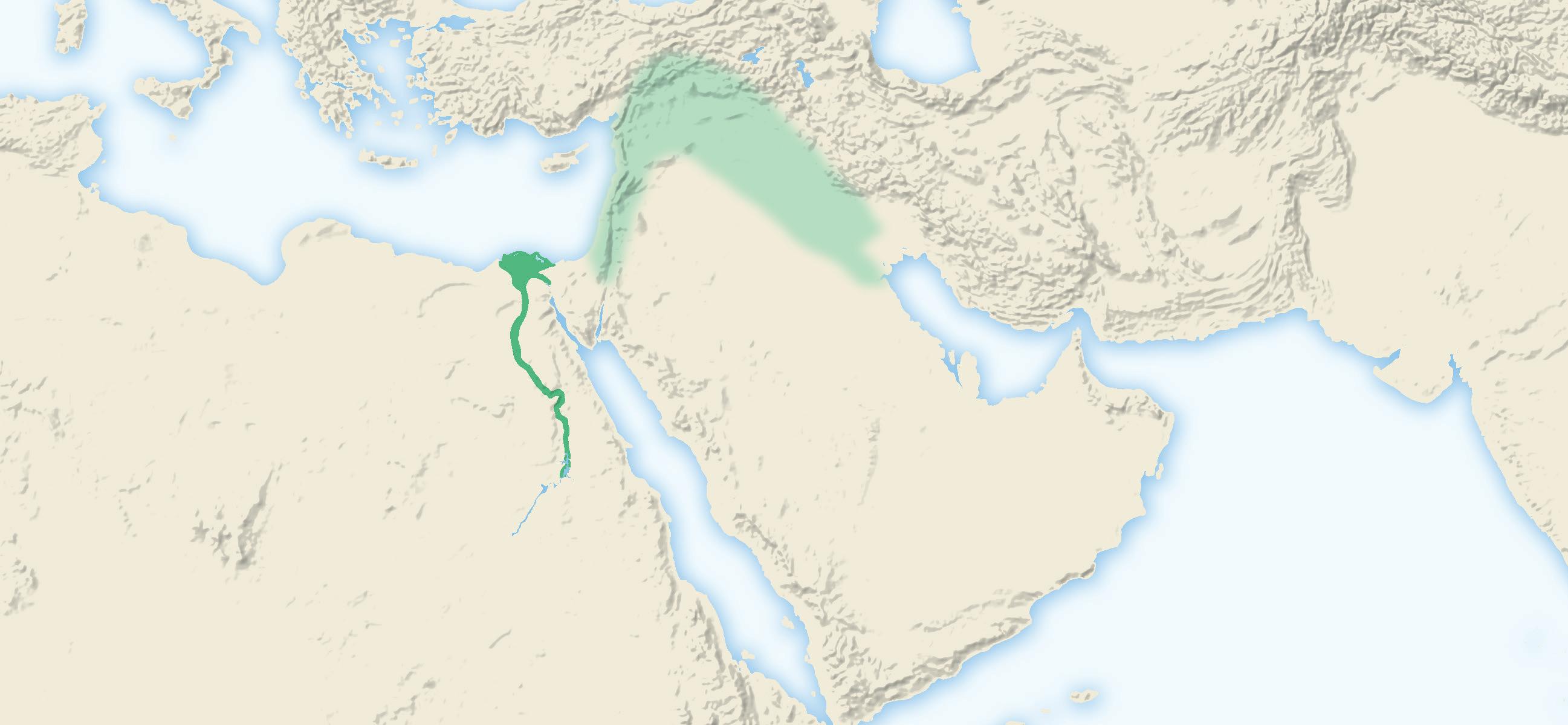

Geography and the Early Settlement of Egypt, Kush, and Canaan 176

How did geography affect early settlement in Egypt, Kush, and Canaan?

Lesson 12

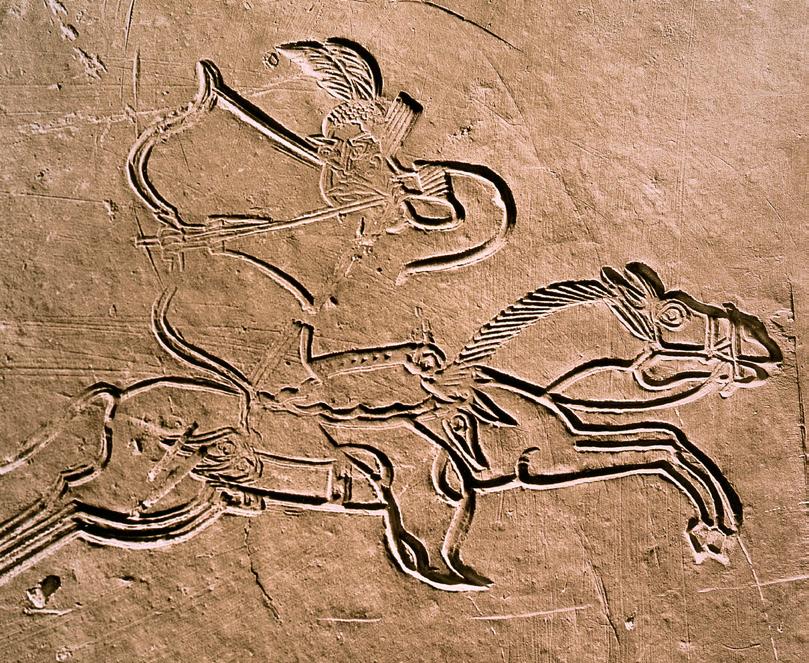

The Ancient Egyptian Pharaohs 184

What did the pharaohs of ancient Egypt accomplish, and how did they do it?

Exploring the Social Sciences – The Egyptian Mummy Project

Lesson 13

Daily Life in Ancient Egypt 196 How did social class affect daily life in ancient Egypt?

Investigating Primary Sources – What Was It Like to Be a Scribe in Ancient Egypt?

Lesson 14

The Kingdom of Kush 214 How did location influence the history of Kush?

Lesson 15

The Origins of Judaism 220 How did Judaism originate and develop?

Lesson 16

Learning About World Religions: Judaism 230

What are the central teachings of Judaism, and why did they survive to modern day?

Unit Closer

Studying Sources 238 Timeline Challenge 24 2

Unit Opener

Geography Challenge 24 4 Inquiry Project 24 8

Lesson 17

Geography and the Early Settlement of India 250

How did geography affect early settlement in India? Exploring Connections to Today – Saving the Ganges

Lesson 18

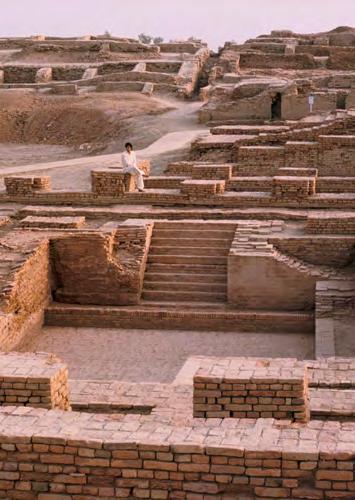

Unlocking the Secrets of Mohenjodaro 26 4

What can artifacts tell us about daily life in Mohenjodaro?

Lesson 19

Learning About World Religions: Hinduism 274

What are the origins and beliefs of Hinduism?

Lesson 20

Learning About World Religions: Buddhism 284

What are the main beliefs and teachings of Buddhism? Investigating Primary Sources – What Are Different Ways Buddhist Principles Were Passed Down?

Lesson 21

The First Unification of India 296

How did Ashoka unify the Mauryan Empire and spread Buddhist values?

Lesson 22

The Achievements of the Gupta Empire 302

Why is the period during the Gupta Empire known as a “golden age”?

Unit Closer

Studying Sources 314 Timeline Challenge 318

Geography Challenge 320 Inquiry Project 324

Lesson 23

Geography and the Early Settlement of China 326

How did geography affect life in ancient China?

Lesson 24

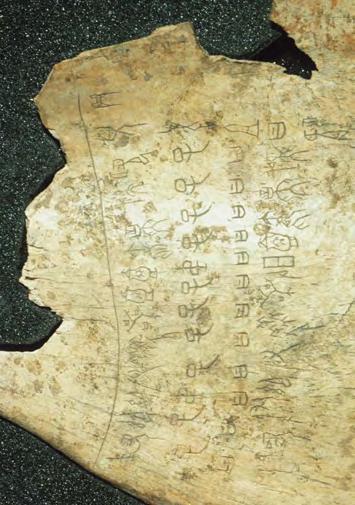

The Shang Dynasty 338 What do Shang artifacts reveal about this civilization?

Lesson 25

Three Chinese Philosophies 348 How did Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism influence political rule in ancient China?

Lesson 26

The First Emperor of China 358 Was the Emperor of Qin an effective leader? Exploring Perspectives – China’s Great Walls

Lesson 27

The Han Dynasty 370

In what ways did the Han dynasty improve government and daily life in China?

Lesson 28

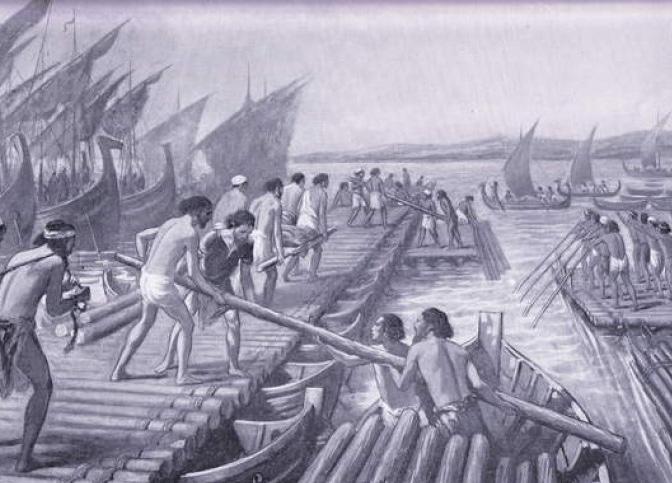

The Silk Road 380

How did the Silk Road promote an exchange of goods and ideas?

Investigating Primary Sources – How Did Geography Affect Travelers Along the Silk Road?

Unit Closer

Studying Sources 394 Timeline Challenge 398

Geography Challenge 4 00 Inquiry Project 4 04

Lesson 29

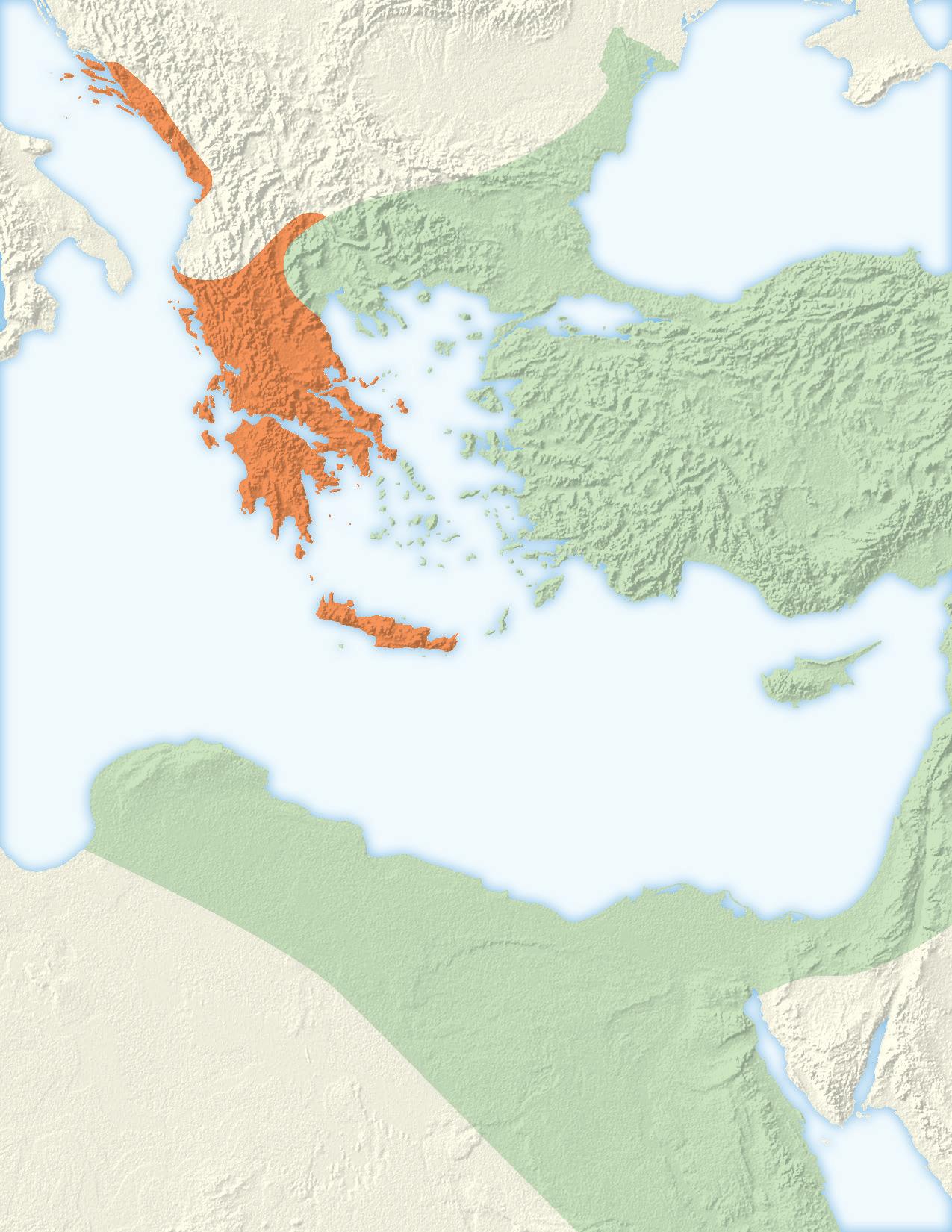

Geography and the Settlement of Greece 4 06

How did geography influence settlement and way of life in ancient Greece?

Lesson 30

The Rise of Democracy 412 How did democracy develop in ancient Greece?

Lesson 31

Life in Two City-States: Athens and Sparta 418 What were the major differences between Athens and Sparta?

Lesson 32

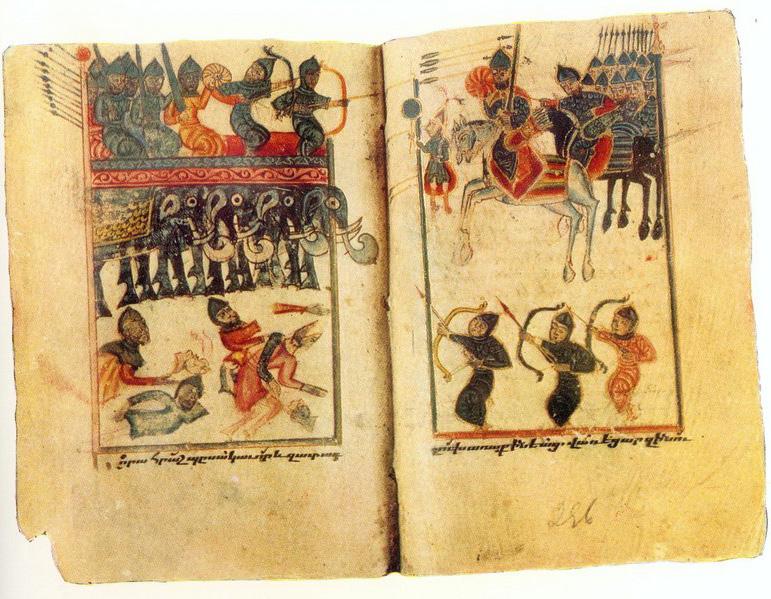

Fighting the Greco-Persian Wars 4 30 What factors influenced the outcome of the Greco-Persian Wars?

Lesson 33

The Golden Age of Athens 4 40 What were the major cultural achievements of Athens? Investigating Primary Sources – What Do Dramas of Ancient Greece Reveal About Its Society?

Lesson 34

Alexander the Great and His Empire 4 54 How did Alexander build his empire?

Lesson 35

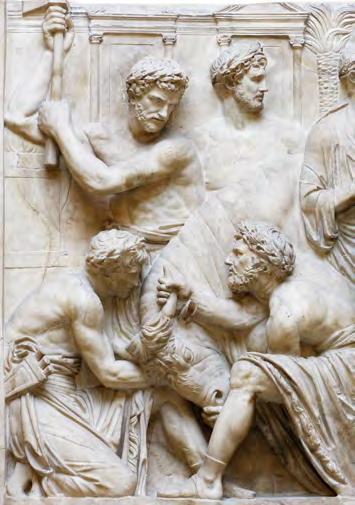

The Legacy of Ancient Greece 4 62 How did ancient Greece contribute to the modern world? Exploring the Social Sciences – Painting the Gods

Unit Closer

Studying Sources 474

Geography Challenge 4 80 Inquiry Project 4 84

Lesson 36

Geography and the Early Development of Rome 486

How did the Etruscans and Greeks influence the development of Rome?

Lesson 37

The Rise of the Roman Republic 4 94

What were the characteristics of the Roman Republic, and how did they change over time?

Lesson 38

From Republic to Empire 50 0 Did the benefits of Roman expansion outweigh the costs?

Lesson 39

Daily Life in the Roman Empire 512 How did wealth affect daily life in the Roman Empire? Investigating Primary Sources – Why Did Gladiators Fight?

Lesson 40

The Origins and Spread of Christianity 528 How did Christianity originate and spread?

Lesson 41

Learning About World Religions: Christianity 538

How are Christians’ lives shaped by the beliefs and practices of Christianity?

Lesson 42

The Legacy of Rome in the Modern World 5 46

To what extent does ancient Rome influence us today? Exploring Connections to Today – Lessons from Pompeii

Unit Closer

Studying Sources 562

Challenge 566

Geography Challenge Watch a video to explore how geography is a useful tool when studying ancient history. Then use the maps and reading to answer the Geography Challenge questions in your notebook.

Inquiry Project Explore a compelling question of your choosing. Then complete a Student-Directed Inquiry. Gather evidence throughout the activities, reading, and additional research to write an argument that answers the question by the end of the unit.

1 Investigating the Past Through Inquiry Play the role of detectives, interpreting cave paintings and artifacts to discover clues about how prehistoric humans lived.

Key Skills: Making Predictions, Framing Questions to Research, Drawing Sound Conclusions

2 T hemes of World History Analyze images of events in the ancient world. Research one key invention from the ancient world and present your ideas.

Key Skills: Selecting Useful Information, Identifying Frame of Reference and Point of View, Sequencing Events

3 Early Hominins Analyze images of hominin groups and explore how adaptations gave later hominin groups advantages over earlier groups.

Key Skills: Creating a Timeline, Analyzing Cause and Effect, Drawing Sound Conclusions

4 From Hunters and Gatherers to Farmers Create a comic book about two Stone Age characters based on the Neolithic development of agriculture.

Skills: Comparing and Contrasting, Framing Questions to Research, Map Skills

Studying Sources Use these readings as further sources for your Inquiry Project and to deepen your understanding of the content:

• Explore – Library and Information Literacy Skills

• Explore – Piecing Together the Story of Early Hominins

Then look for additional sources online, including Explore, Primary Source, Literature, and Biography readings.

Timeline Challenge Review the key events from this unit by sequencing events on a timeline. Then add your own events that you consider to be important in history.

in to access a video-based

Challenge and Video Activities that explain the main ideas of the text with meaningful visuals.

Maps are useful tools that show where things are on Earth. They can also help you learn about the history of people and places and the interactions between them.

There are a few essential elements that can be found on any map. A map’s title describes the area shown on the map and identifies the main topic of the map.

To indicate directions, mapmakers include a small diagram called a compass rose . The points of the compass rose are

with the cardinal directions— north, south, east, and west. The points in between, such as northeast, are called intermediate directions.

Many maps include a map scale, which tells you how to read distances on the map. For instance, an inch on a map might equal 10 miles, 100 miles, or even 1,000 miles on Earth. Additionally, if symbols are used on a map, they are identified in a box known as the map key

You can begin to study a place by finding its absolute location, or “address” on Earth. Lines of latitude and longitude can pinpoint any place on Earth. Distances between these lines are measured in degrees (°).

The first set of lines, parallels of latitude, run east and west around the globe. The starting point for measuring latitude is the equator at 0° latitude. The other set of lines are called meridians of longitude. They run from the North Pole to the South Pole. Meridians of longitude start from 0° at the prime meridian.

The equator divides Earth into halves called the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere. Similarly, the prime meridian divides Earth into the Western Hemisphere and Eastern Hemisphere. Within these hemispheres sit Earth's seven continents, or large landmasses, and five oceans.

In addition to absolute location, maps also show the relative location of places on Earth. This is the location of one place compared to another place. For example, Africa is southwest of Asia.

Follow the steps below to complete a Student-Directed Inquiry during this unit. Use the activities and disciplinary sources to build your knowledge and gather evidence. Then construct an argument that answers the compelling question.

Developing Questions

Preview the unit. Scan the titles, essential questions, and images. Brainstorm questions that you have about the topics in this unit.

As you complete the readings and activities in the unit, narrow down and revise your list of questions until you have reached one compelling question for the unit. Consider choosing a topic that allows you to investigate social scientific problems—historical or current.

As you write your compelling question, ask yourself:

• Does it express a problem or question that interests you?

• Is it open-ended? Is it complex enough that it’s worth digging into?

• Can you propose an argument that attempts to answer the question?

Using Disciplinary Sources to Build Arguments

[student-generated]

Brainstorm 2–3 supporting questions that will help you explore your compelling question.

Identify sources that might provide evidence to answer your compelling question. Choose different types of sources that are from a variety of perspectives. Consider the reliability of each source:

• Is it a quality source? Is it from a government or educational website or a respected newspaper, magazine, or journal?

• What is the perspective of the source? In what ways might the source be biased?

Record information from the sources that you will be able to use as evidence to support your argument.

Construct an argument that addresses your compelling question. Make sure to:

• Begin with a strong claim, which you then support with at least three pieces of evidence from your research.

• Use reasoning to connect your examples and evidence to your claim.

• Acknowledge the strengths and weaknesses of your argument.

Extension Use an alternative method to present your argument. You could create a poster, a podcast, or a digital presentation.

Brainstorm ways that the information you learned connects to your school, community, or state.

For example, think about the challenges people faced and actions they took to address issues at different times and places during the unit.

What did you learn that inspires you to help others around you?

Brainstorm ways that you could use the information you learned to improve your school, community, or state.

Some options:

• Record a podcast

• Create a poster or a digital presentation

• Conduct a discussion with your classmates or family

• Research opposing views; refine your own argument

• Create or join a social media group

• Make a video or public service announcement

Brainstorm ways that you could get engaged. How can you be a leader to enact change?

Some options:

• Volunteer your time

• Donate money

• Organize a fundraiser

• Start a charity

• Help others follow a current law

• Advocate to adjust a law or policy

• Organize a rally

• Speak at a school or community event

• Contact local, state, or national legislators

Inquiry Project Go online to complete the activities, readings, and tasks. Fill out the corresponding prompts for each step in your print or online notebook.

Classroom Activity

how

role of

past

and interpret

about how social scientists investigate the past through a video covering the main ideas of

Activity

an online activity to show what you’ve learned.

lesson

your online or print Interactive Student Notebook to bring meaning to the reading you’ve completed.

Text with Notes

Welcome to the world of ancient history. Studying history involves investigating what happened in the past and why. Ancient history concerns the distant past, from the earliest humans through the first great civilizations.

How can we learn about events that happened so long ago? People who study history are a lot like detectives conducting an investigation. They ask questions, study the evidence for clues, and form hypotheses (educated guesses based on evidence).

Our investigation of the ancient past starts near the very beginning of human history. What was life like long, long ago?

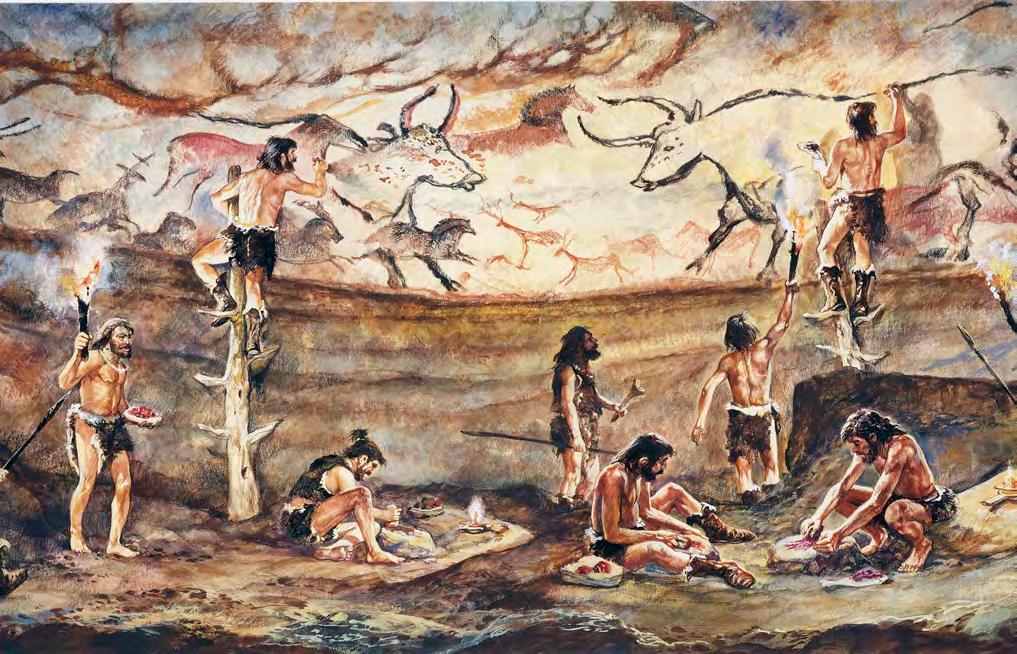

One amazing clue about life long ago was discovered at Lascaux (lah-SKOH), France, by four teenagers. On September 12, 1940, the boys found a cave. Covering the walls and ceiling of the cave were what appeared to be very old paintings of animals. Some of the figures look similar to modern-day animals, such as horses or bulls. Who had created these large paintings? When were they composed, and what did they mean?

How would you solve a mystery like this one? The clues are millennia old, and the witnesses are long gone. You might need the help of an expert detective, but who would that be?

In this lesson, you’ll meet three kinds of experts who study the past. You will discover how they analyze and interpret clues left throughout history. Then you will look at some fascinating examples of cave art to see what this evidence can teach us about life long ago.

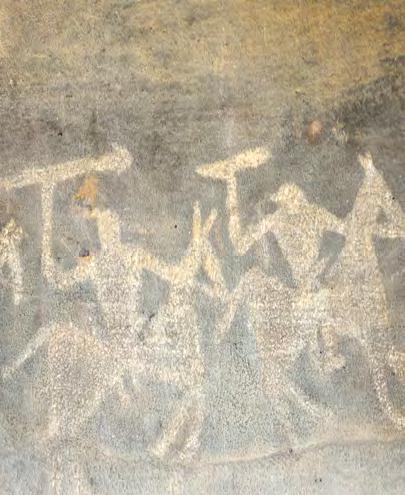

Scholars study cave paintings, like this one found in Lascaux, France, to learn how humans lived long ago and study clues about their cultures.

Social Studies Vocabulary archaeologist argument artifact bias compelling question geographer historian inquiry prehistoric primary source public policy ritual secondary source supporting question

archaeologist an expert who studies the past by examining objects that people have left behind historian an expert who studies and records the past

geographer an expert who studies and creates maps of Earth’s natural and humanmade features

artifact an object made or used by people in the past prehistoric before written history

Scholars who study human society are called social scientists. Many social scientists can help us study the past. Among these “history detectives” are archaeologists, historians, and geographers.

Archaeologists: Digging Up the Past Archaeologists study the past by examining objects, or artifacts, that people have left behind. These artifacts are anything made or used by humans, such as clothing, tools, weapons, and coins. When archaeologists uncover a place that has artifacts, they ask questions like these: Who lived in this place? When did they live here? What were they like? Then archaeologists study the artifacts for clues.

Archaeologists use tools to delicately retrieve artifacts, which give them clues about the past. A grid system is often used to organize where on a site each artifact was found.

Historians: Recording the Past Historians are the recorders of the past. Human beings have been around for such a long time that historians tend to focus mostly on the last few thousand years, when people began leaving written records. Historians want to answer this question: What happened in the past? To find out, they study all kinds of artifacts and documents, including diaries and letters. Besides asking what happened in the past, historians try to understand why events happened the way they did.

Geographers: Mapping the Past Geographers study the natural features of Earth, such as water, landforms, plants, and animals. They also look at human-made features, such as towns, roads, bridges, and dams. These scientists help us answer such questions as: Where did people live? How did they use their environment to survive? Geographers often create maps to show what they have learned.

Social scientists who study prehistoric his tory face a unique challenge—a lack of evidence from this period. In fact, huge gaps of time have no evidence at all. Therefore, scientists may come up with different answers or theories about how humans came to be.

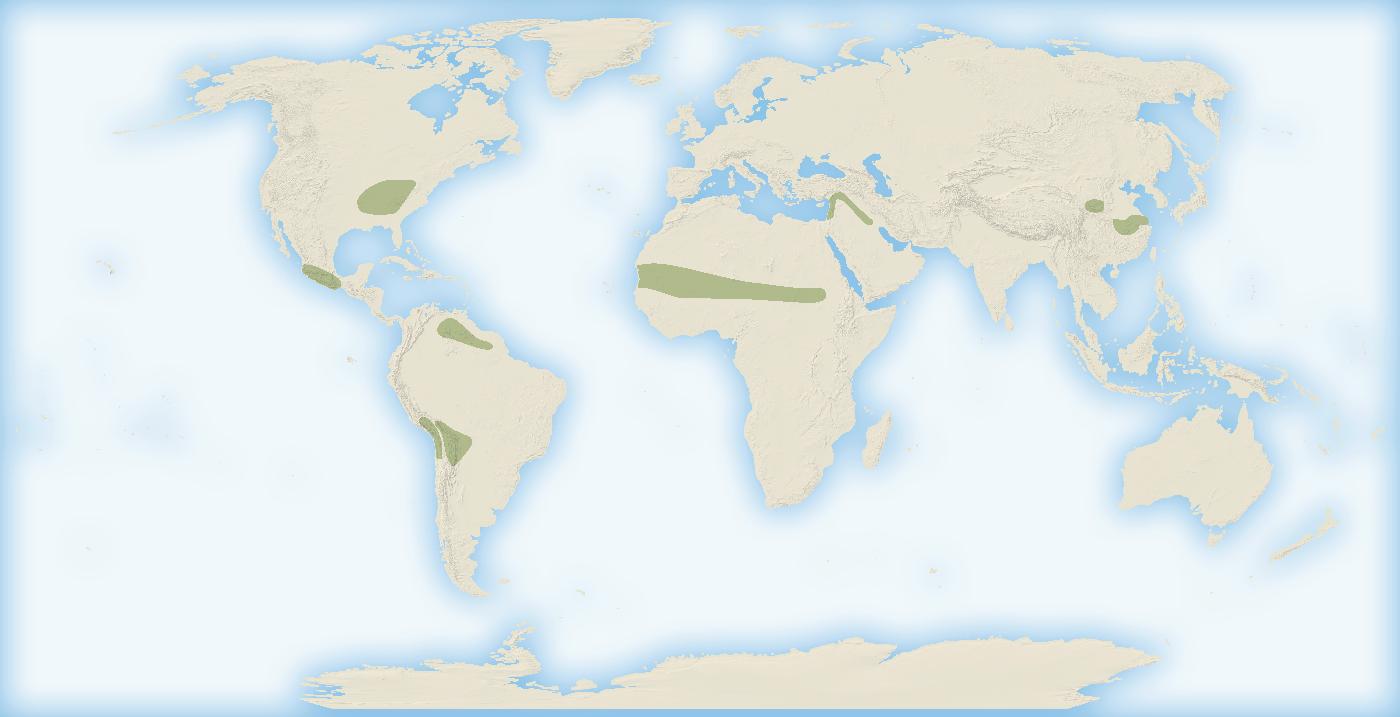

Cave paintings like those at Lascaux, France, provide clues about what life was like in prehistoric times, before writing was invented. Caves with paintings that are thousands of years old have been discovered all over the world. Some paintings show what kinds of animals roamed the Earth and what methods people used to hunt them. Often, the paintings provide hints about people’s beliefs.

Many of the rooms decorated with paintings are deep inside the caves. Scientists believe that cave artists used torches to work in these dark places. Some paintings are very large in size and taller than a person’s height. Some paintings are found on high ceilings. Scientists think that prehistoric artists built scaffolding, or planks raised above the floor, to reach the highest places.

Caves have also provided information in the form of artifacts. Scientists have found lamps for burning animal fat and tools for painting and engraving. Cave paintings and artifacts are amazing treasures that can help answer many questions about how humans lived in ancient times. But, as you will see, these treasures also raise new questions for scientists to puzzle over.

Cave painters developed a variety of methods for applying paint to walls of a cave. This artistic rendition shows a number of these techniques. Can you identify any?

This hunting scene possibly shows items used in special ceremonies. Notice the weaponry the hunters are holding.

This painting was found inside a cave at the Bhimbetka rock shelters in India. It was painted between 4,000 and about 10,000 years ago. The painting shows a scene from a hunt in which riders on the backs of animals are holding a weapon. This weapon is a spear, which was typically hurled with a spear thrower. The animals resemble a horse or similar species. The legs of the animals make them appear in motion.

Paintings of humans are less common in cave art. Notice the simple drawing of the hunters, each in the same body position. The animals are much more realistic with their ears and tails.

Many social scientists suppose this painting was created as part of a hunting ritual. The artist may have been asking for a successful hunt. It is also possible that the painting is a record of an actual event, or it may simply be a decoration.

This painting, found at Lascaux, was created more than 17,000 years ago. It shows many prehistoric animals, such as bulls, elk, and horses. But the public cannot view all of the animals at Lascaux. Parts of the cave have been closed in order to protect the art.

ritual relating to a ceremony, such as a religious ceremony

The painters used the cave’s uneven walls as part of their composition. In the bottom left of the image, a ledge juts out from the wall. The artists painted the bulls to look as though they were standing on top of it.

Scientists have many ideas about why animal paintings were created, such as that the artists were trying to capture the “magical powers” of certain animals. Another theory is that the painters believed in the spirit world and were creating art to honor or influence their gods. Some scientists speculate that caves were places of worship and that paintings were used in rituals or ceremonies.

Historians still wonder why these animal paintings were created. Perhaps the difference in coloring among the animals provides a clue. What do you think?

The handprints seen in this cave painting are very small. Prehistoric people were probably smaller in size than people are today.

This painting is in a cave called the Cueva de las Manos, or Cave of Hands, in Argentina. It shows a circular shape, multiple animals, and several handprints.

Paintings of shapes and handprints are fairly common in cave art. Many scientists suggest that handprints were a way for artists to sign their paintings. Some scientists think that geometric shapes had special meanings in rituals.

Researchers tried singing inside one painted cave in France. They discovered that the sound was loudest in the painted areas, and therefore supposed those areas were probably used for special gatherings.

In prehistoric times, spears were often lodged inside a spear thrower, which would release the weapon faster than when normally thrown. This image shows the top of one type of spear thrower that has broken away from the rest of the device. Found in France, it was made from a reindeer antler bone about 15,000 years ago. It now measures 12.4 centimeters long but would be much longer if it was fully intact.

This spear thrower top depicts a mammoth. The artist engraved, or carved, the eyes and legs to show details in the animal. The artist must have cared a great deal about decorating this important hunting tool.

Some scientists think that the artist carved the mammoth as decoration for a spear thrower, but the carving may have been a good-luck charm to protect the hunter or make them more successful. It also could have some relation to the hunter’s name, or even been a way of identifying the clan or group that the hunter belonged to.

This sculpture of a mammoth is the only known spear thrower to have holes for eyes. Historians believe that this shows an advance in prehistoric tools and a very skilled artist.

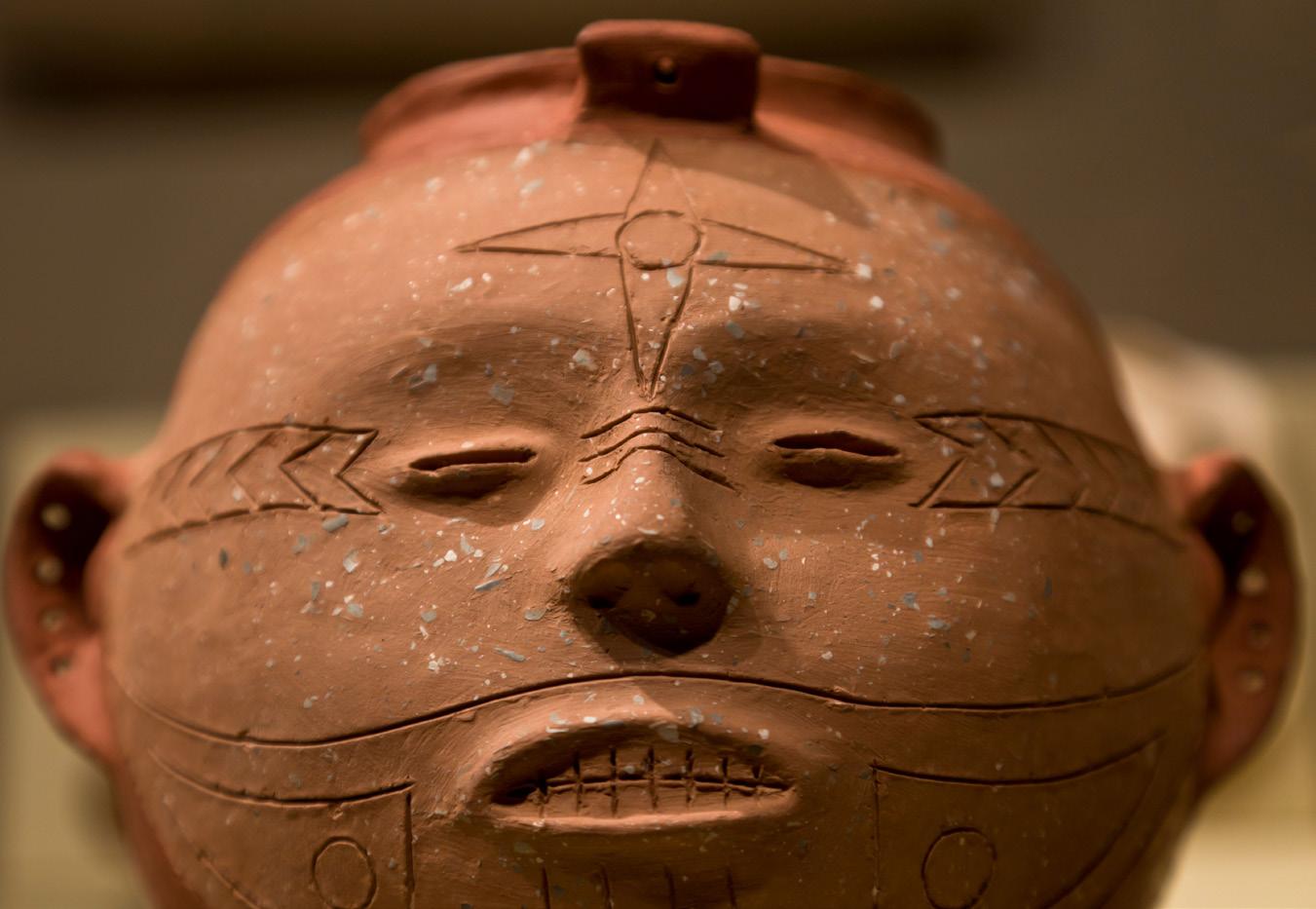

This clay sculpture may offer clues about the people who made it and why. Historians suggest it was a significant part of a coming-of-age ceremony.

This clay sculpture of a bison was found in a low room, deep inside a cave in France. It was made about 10,000 to 14,000 years ago and measures about 24 inches in length. The artist sculpted it from goldcolored clay. Carved lines show details such as the animal’s face, coat markings, and the fringe of fur below its powerful neck.

Scientists have two main ideas about why this sculpture was created, one of which is that the sculpture was meant to show that the cave belonged to a certain clan. The other idea is that the sculpture was used in an important ceremony held deep inside the cave. Perhaps it was a coming-of-age ceremony to show that a person had passed from childhood to adulthood. One clue that supports this idea is the footprints of young people that have been found near the sculpture.

Prehistoric tools included engraving tools, grinding stones, and scrapers. Scientists study tools like these and try to guess how they were used.

For example, scientists think that cave artists made paints by grinding colored minerals into powder on grinding stones. The artists then probably mixed the powder with animal fat or vegetable oil to create various colors. When the artists wanted to include the color white in their paintings, they used scrapers to remove the top layer of rock to reveal a white layer.

You’ve already seen how prehistoric artists engraved some of their art. For painting, they may have used brushes made of moss, fur, or human hair. They may even have blown paint through hollow tubes to create softer textures, such as shaggy winter coats on horses.

Cave artists used tools made of sharpened stones to grind minerals for paints. Other stone tools were also used to sculpt and engrave objects and cave walls.

Historians and archaeologists have collected evidence of how prehistoric humans lived. They put that evidence into a story of past events that is accurate and meaningful. To carry out their work, they follow certain methods to help them understand information. French poet and author Jacques Yonnet compared the work of a historian to that of a detective.

Modern historians follow professional standards. Unfortunately, these standards were not clearly established in the past. For example, in the early days of archaeology, scientific procedures were not laid out well. Nearly anyone with the money, the time, and the interest could select a promising site and start digging in search of history.

This led to many problems. In a lot of cases, the early archaeologists were foreigners. Yet they collected ancient statues, pottery, and other things from tombs and burial sites and sent them to other countries. Today, many countries are demanding the return of these artifacts.

Another problem was that amateur historians often destroyed what did not interest them in order to find the flashy treasures they were after. This has made the later work of serious historians much more difficult. But it has also caused them to re-evaluate their priorities. Today, they try to carefully consider what might be destroyed as they excavate a site.

Finally, historians today realize that they must be honest about what they plan to do with their findings. For example, if DNA was collected from a particular ethnic group for a specific reason, the DNA cannot be used for another reason.

Suppose that DNA was collected to discover whether an Indigenous community had a pattern of diabetes. The commu nity agreed to this. Other researchers, however, would not later be able to use that DNA for other research, such as discovering whether this community shared DNA with Indigenous groups in South America. They would first need to gain permission for this new research. Public policy like this helps to protect the privacy of regular people and makes sure the collection of data is fair and focused.

The tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun was discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter. Most of the artifacts found in this tomb remain in a museum in Cairo, Egypt, the country it was found in. However, there are concerns that many valuable artifacts were removed from the country. It will probably never be known for certain what was stolen.

public policy the laws and regulations that determine how problems can be solved in response to social issues

inquiry in history, the process of exploring the answers to questions about a certain time and place

primary source a document or other record of past events created by someone who was present during the events or the time period in which they occurred secondary source a document or other record of past events created by someone who was not present during the events or the time period in which they occurred

History Begins with a Question or Problem Historians usually begin their work by finding a question they hope to answer or a problem they wish to solve. These questions often focus on how or why an event happened, rather than simply asking what occurred.

Historians first have to make an observation about the real world. A historian studying ancient China might note that many religions spread across Asia during the period of the ancient Silk Road. This is an early step in the process of inquiry.

Historians then use their observations to form their ques tions. One example question might be, How did the ancient Silk Road trade routes help spread religious ideas across Asia? With this question in mind, a historian will come up with a possible explanation that they believe answers this question. This expla nation is called a hypothesis.

Historians Select and Weigh Evidence Next, they col lect facts and information related to the question. This material becomes the evidence, or information that can be used to prove a statement or support a conclusion.

Photographs are visual primary sources that show what life was like in the past.

Historical evidence comes in multiple forms. It might be an old letter, a manuscript, or an artifact. Sometimes public policy may limit how or where artifacts may be dug up or stored. Evidence can also be found in photographs, music, and movies. Additionally, it can be found in books, newspapers, and in interviews with experts or historical figures.

Historians call these various forms of information sources. There are two basic types of sources typically relied on when writing history. A primary source is a document or other record of past events created by people who were present during those events or during that period. The journal of a Silk Road traveler would be a primary source.

A secondary source, in contrast, is a document created later in time, often by experts. Examples include a book or accounts from someone who was not present at the events in question or perhaps not even alive during that period. Many secondary sources are created decades or even centuries after the events in question. A modern history book that includes information about the Silk Road would be a secondary source.

Sometimes a source contains information or conclusions that show a clear point of view. Although this is not necessarily bad, his torians are watchful for signs of bias when analyzing evidence. Bias takes many forms, ranging from a simple friendship or preference for someone to an unfair dislike of a person or group. Regardless of its form, bias can make a source less than trustworthy.

All historical evidence must be critically evaluated. Historians carefully examine each source for the creator’s point of view, perspective, or outlook on events. This outlook may be influenced by multiple factors, such as the person’s age, gender, religion, occupation, or political views. For example, a historian would expect that a Chinese Buddhist pilgrim traveling along the Silk Road would have had a point of view different from that of a European merchant.

Historians Interpret Their Findings Once their evidence is selected and evaluated, historians begin to reconstruct what happened. They often begin by establishing a chronology, or sequence of events in time. Once historians are certain of the correct order of events, they are better able to make connections among those events, like identifying causes and effects. However, the more challenging part of a historian’s task is to interpret the past—to weave together the evidence and help readers under stand and draw meaning from history.

The process of finding the meaning or significance of histori cal events is called historical interpretation. By interpreting history, historians combine their analysis of events with the facts they have validated in order to create a general theory about what happened in the past. This theory often includes what hap pened, how and why it happened, what effect it had on the people involved, and how it may have shaped the world today. Each historian brings a particular point of view to this task. However, historians try to ensure that their interpretations are faithful to the facts of history and are supported by the evidence.

History Is Never Finished Much of history is still open to interpretation. In fact, historians often make opposing arguments regarding the past. Because historians have different backgrounds and points of view, their interpretations will often differ. They publish their work with the understanding that it will be reviewed, and often criticized, by other historians. In this way, history continues to be debated and revised.

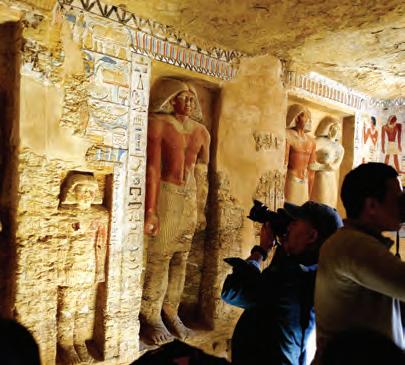

bias a personal leaning or a preference for a particular outlook argument the position that researchers take about a particular topic, based on the evidence that they have gathered Discoveries may change understandings of the past as new artifacts or sites are explored, such as newly found objects or tombs from ancient Egypt.

compelling question a question that does not have a simple or direct answer and requires some thought and investigation to answer

There’s no better way to understand the process historians go through than to conduct your own inquiry into history. An easy way to do this is to investigate something about your own community. As we review the steps in a historical inquiry, we will take a closer look at some historical investigations that will give you additional tips on what to do and what to avoid.

Begin by brainstorming to arrive at a compelling question. You might start with a list such as this one:

• Who were the first people in your area?

• What are the town’s origins? How did it get its name? Who were the town’s founders? What are some of the famous or key events that have happened?

• What are some natural landmarks (for example, the oldest tree)? What are some long-standing businesses, which may have supported a large part of the community or been a local favorite, such as a barber shop?

• What are some legends or stories about your town?

■ Ask a Compelling Question

W hat do you want to know about an event or topic?

■ Ask Supporting Questions

How can you better understand an event or topic? What facts can be uncovered?

■ Apply Social Studies Concepts

How do your questions connect to related areas such as civics, economics, geography, and history?

A re your sources mostly primary or secondary? Are they reliable?

Discuss with other students and your teachers. How could you share your conclusions with your community?

Did your research uncover a problem? Is there a way to make the his tory you learned about more relevant to your school or community?

Today we can study Minoan clay figures ourselves. We can ask who these figurines represent. But we should use only evidence to find our answers, and not imagine the answers.

Before 20th century research standards for archaeology were established, the field often attracted well-to-do amateurs who had the wealth to pursue their hobbies in these fields.

Sir Arthur Evans knew a great deal about ancient Mediterranean cultures, pos sibly more than many in his field. He funded his excava

tions of Crete, which led to knowledge of an entire new world. But was the world he discovered accurate? Evans imagined a woman-oriented society. When he discovered parts of small female statues, he already had a clearly imagined idea of what that culture would look like. When the statues he found did not meet his

imagination, he pieced together statues from the ruins to fit his idea.

Evans had a compelling question: What was the Minoan culture like? But he made the mistake of answer ing his compelling question before carefully weighing the evidence.

Most strong research begins with a compelling question. This compelling question may lead to a very clear line of research. However, it might also create new and interesting questions around an event or topic.

Inquiry in Action After reviewing the brainstorming questions in a group session, Erika, a sixth-grade student in Maryland, is interested in the question of legends about her town. She lives in a suburb, but the older kids have always told stories about the unusual mansion at the edge of their neighbor hood. It sits on a low ridge surrounded by trees. It is nothing like the rest of their homes that all look so similar. One Halloween, a high school girl told everyone nearby that the mansion used to be an important stop on the Underground Railroad that helped escaped enslaved people travel from the South up to Canada.

Erika decided that her compelling question was: Did that mansion participate in the Underground Railroad?

Barry, another middle school student in Colorado, had a similar assignment. His older sister who was in college had just spent days talking to the family about how exciting it would be if their town re-opened their railroad station. “People need to be able to travel without getting into a car!” she argued.

He mentioned this in a classroom discussion. His teacher pointed out that their town had once been a popular stop on a regional stagecoach route during the 19th century. “We were prosperous back then too,” he added.

It takes Barry a while to work out his compelling question, to connect the dots. But he finally decides on his question: Are towns more prosperous if they are a part of a strong transporta tion system?

Both Erika and Barry have started with yes/no questions, which they will learn are good starting points, but sometimes may be difficult to answer. We also have to add the questions of When? Who? Where? Why? How?

Local history experts can often help students conduct an inquiry into history.

Supporting Questions

In addition to asking the basic W-Questions, strong supporting questions consider what sources and evidence may be available.

Erika may not be able to answer her question if neither primary nor secondary sources that she finds mention the house she is interested in.

Barry, on the other hand, is asking a question that is too broad. He needs to scale back from what makes all towns pros perous and focus more closely on just his town’s history.

Both Erika and Barry also need to review whether any answers to their supporting questions may be open to interpreta tion. Both of them may benefit from feedback from members of their community who have studied their local history. But even if Erika learns that many others have heard the same legend, she has not yet come across any hard evidence. The things that people tell one another, whether true or not, is sometimes called hearsay. We do not consider something to be evidence just because it has been repeated a lot.

However, if she found someone whose grandparents had worked in that house, she would be closer to an example of primary evidence.

Applying Social Studies Concepts History has many cousins. We learn more about our past from the many fields that also go far back such as art, music, architecture, literature, and philosophy. In the social sciences, historians are also interested in how their compelling questions relate to civics and the way prior civilizations were governed. How do their questions relate to economics and the way people traded and how goods and resources were exchanged? How do their questions relate to geography—the way that the physical landscape impacted a time and place?

supporting question a question that has a concrete answer based on factual information that can be researched and proven; supporting questions will help answer compelling questions

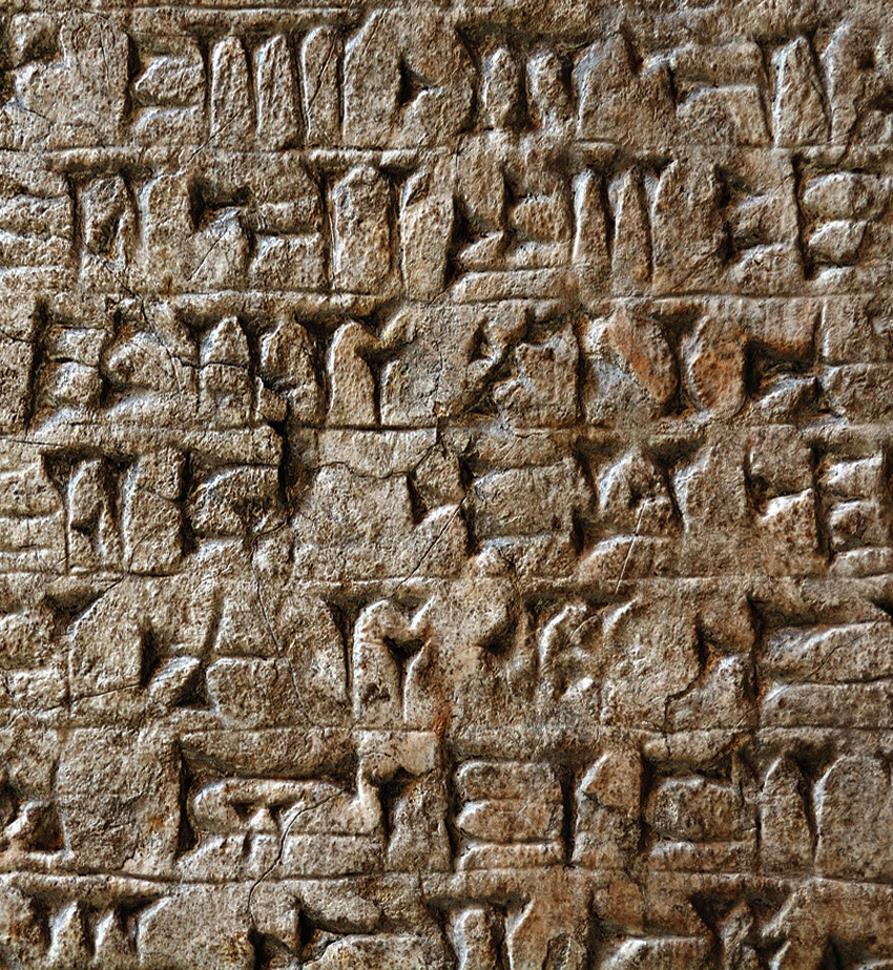

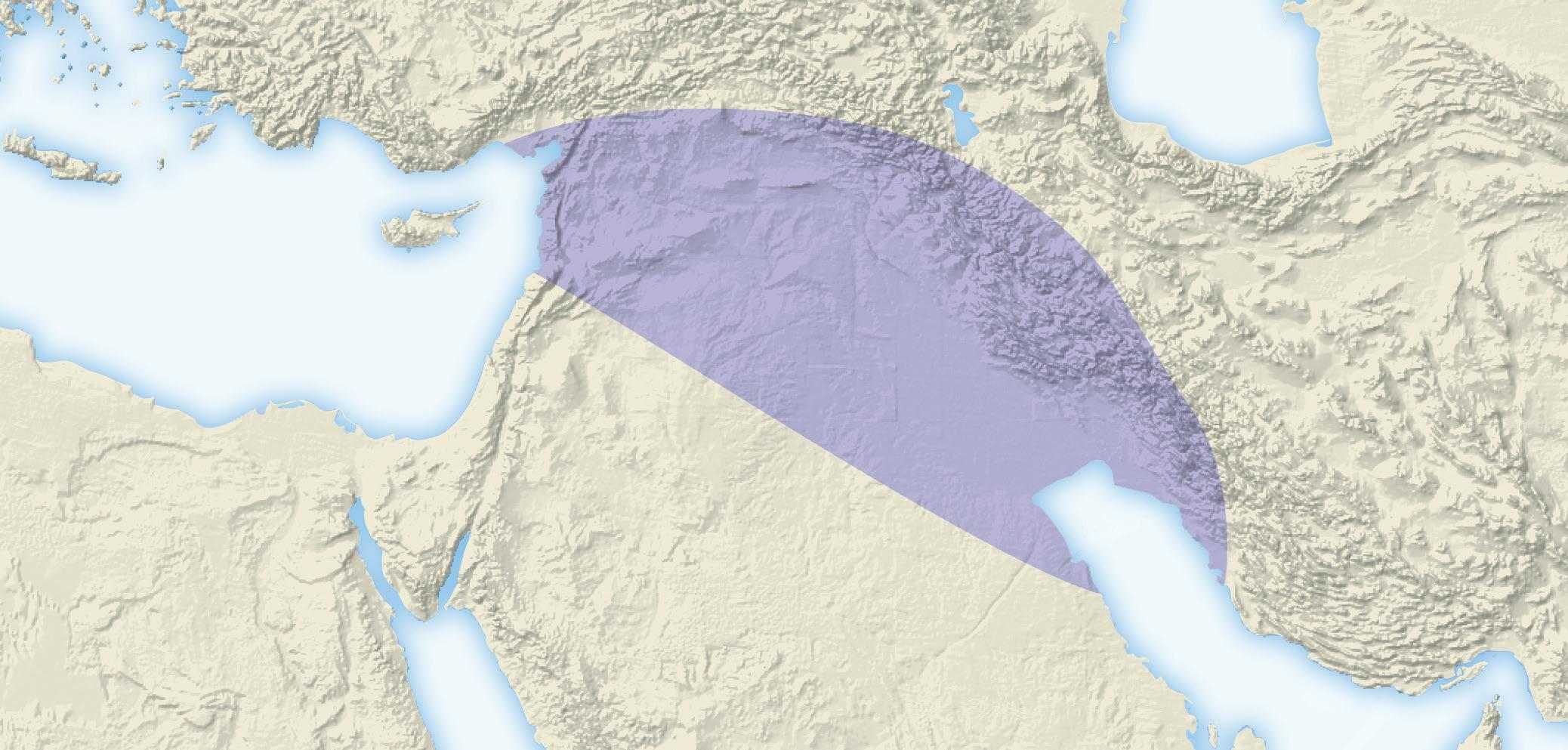

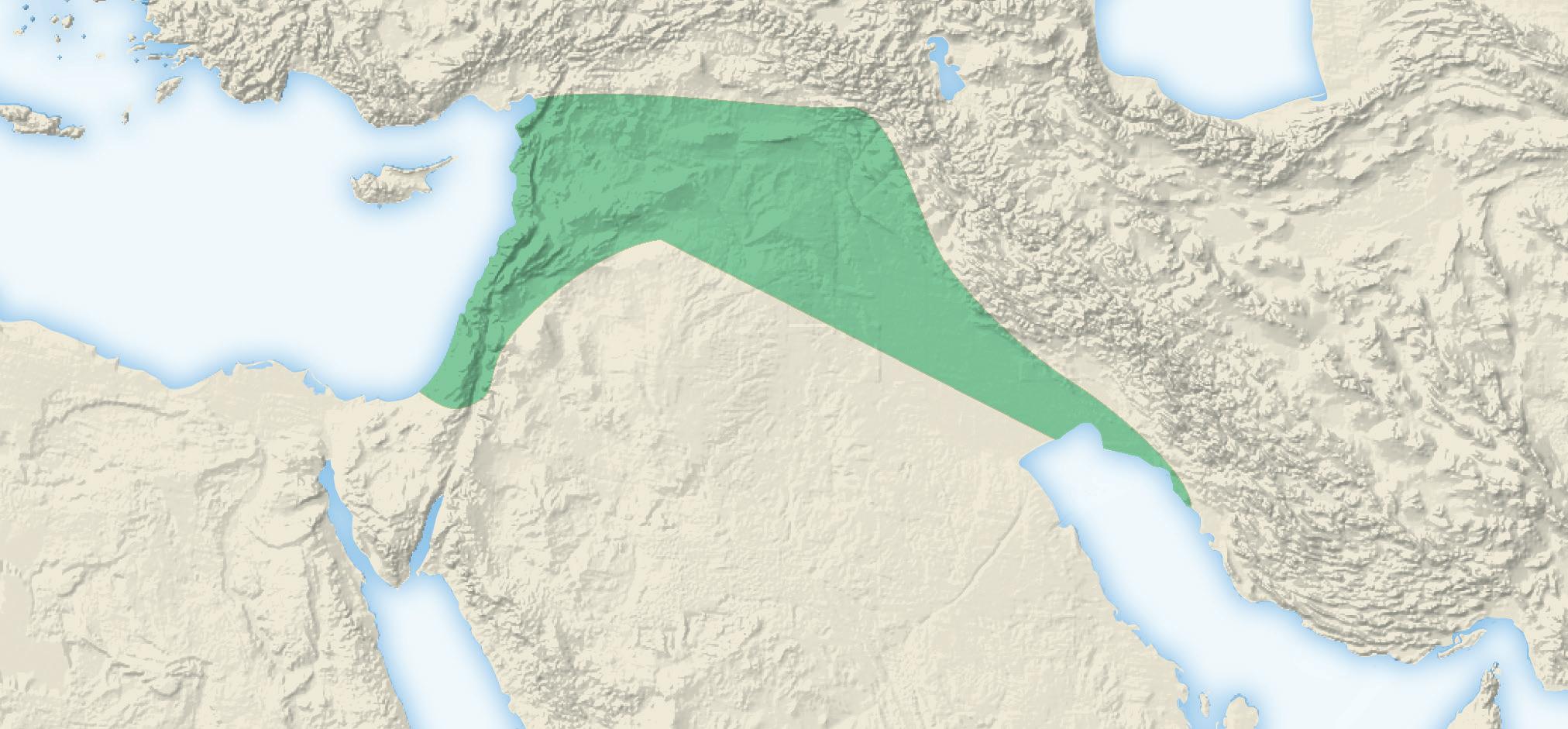

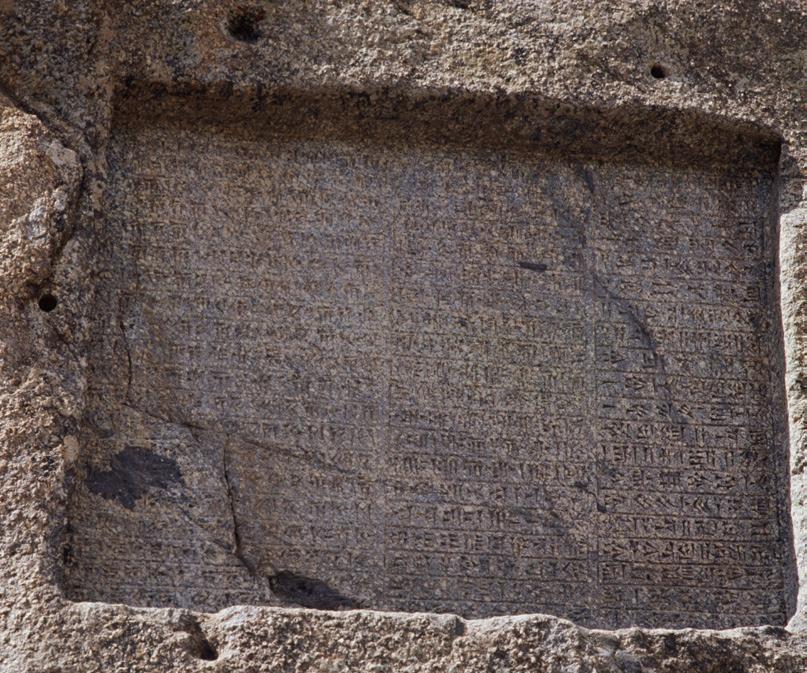

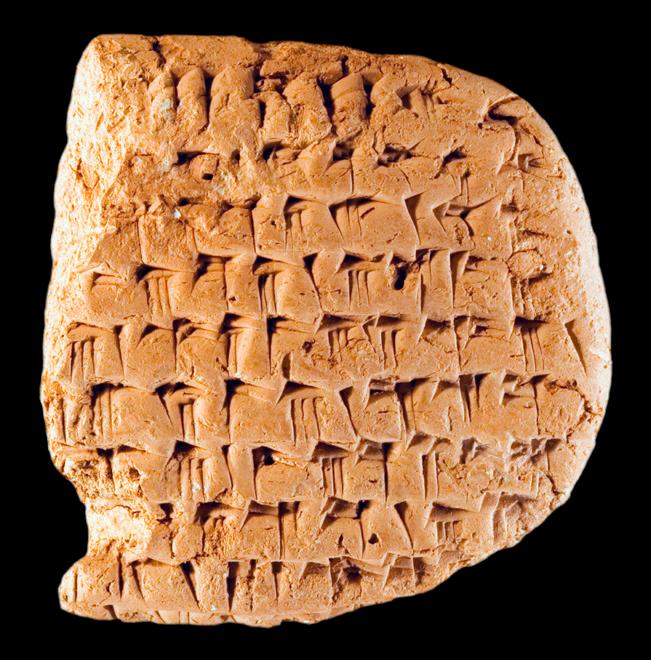

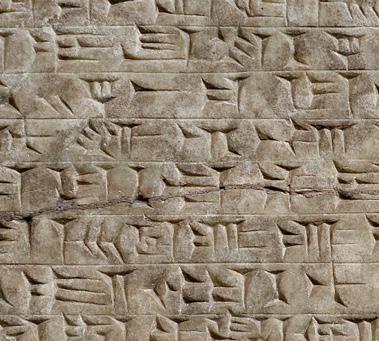

For the last hundred years, scholars have been at work deciphering and interpreting the discovery of over 20,000 letters hammered out in stone. This treasure of evidence was found in what is today Kanesh, Turkey. When the letters were written, Kanesh was a trading town within the Assyrian empire, which existed 4,000 years ago. The Assyrians ruled an area that stretched from present-day Iran through Iraq, Syria, and Turkey.

As historians gradually made their way through this vast new evidence of 20,000 letters, they learned much about how the society functioned, its laws, and government. They learned about the trade network that brought goods from distant lands and places.

Recently, a French historian focused on tablets that were written by women. Cécile Michel’s work showed that women in this civilization were literate, that they were engaged in the family business. And that they could appeal to the social norms to help them.

“I have nothing else apart from these funds,” one woman wrote her brother in cuneiform script. “Take care to act so that I will not be ruined!”

It has taken a lot of time for historians to work through the many letters dis covered at Kanesh. Here and elsewhere, historians continue to ask questions about how ancient societies worked. But it took just one woman to ask the compelling question: In what way were women involved in this civilization?

The Assyrian tablets written in cuneiform script from Kanesh, Turkey, have taken many decades to study and fully understand.

Students can conduct an inquiry process individually or with others. Discussing with others may lead students to uncover a source or question they had not considered.

Both Erika and Barry’s inquiries stretch across civics, economics, and geography. People escaping slavery were break ing the law and so were those helping them. The law was set to protect the economic value that those escaping enslaved people had to their enslavers. And geography mattered enormously. Three days or three steps north and you were free.

As you dive into your inquiry, look closely into the ways civics, economics, and geography relate to the topic you are investigating. By doing so, your findings are likely to become richer and more interesting too, telling a more complete story of the past.

Like the histori ans examining the 20,000 cuneiform letters discovered in Kanesh, Turkey, Barry had given himself a lot of homework. Not only were there hundreds of articles to read in the town’s newspaper, Barry did not believe that he was very good at deciding which were promising. Luckily, his teacher announced that the class could now shift from their individual inquiries and collaborate on the group inquiries of their choice. Three of his classmates joined his inquiry. As a team, they not only cut down the workload, but they brainstormed together and motivated one another.

Leon came to one of their research sessions with a handful of old tourism books his aunt had given him. “It’s not a reliable source, but it may give us some ideas.” In fact, the history section of the tourist guides gave them wonderful ideas on what to search as they plowed through the newspaper archives.

Mai kept them focused. “Remember, we are looking for information to support our claim that prosperity declined after the stagecoach left our town in 1895.”

Routes used by people working the Underground Railroad could take people escaping enslavement over land or sea. Small groups would travel by foot, horse, or wagon to reach safety.

Communicating Conclusions and Taking Appropriate Action Research is carried out in order to contribute to our understanding of our past. After all, if we do not know what our future will bring, we can at least study our past. The lessons there may help us navigate our future as individuals and as a society.

Historians and scientists publish their findings so that other scholars in their field can check their thinking, their evidence, and their conclusions. Sometimes they may meet to discuss find ings. Such close examination of the evidence, this close degree of fact checking, is helpful. It is one more way to guard against bias, bad research collection, and misunderstanding.

Erika discovered through a member of her community who was in her eighties that the mansion had never been a regular stop on the Underground Railroad. Word of Erika’s project had spread, and a friend of a friend of Erika’s mother had come forward. The woman said her grandfather had worked at the old mansion. She had never heard from him that it had assisted people escaping slavery. “I sure wish it had though.”

Erika and her sources resisted Sir Evans’ temptation to write the history that they wanted to hear. Instead, Erika’s research led her to create a map of the homes in her county that had helped the Underground Railroad. After her map was fact-checked by her school, local libraries began to display it on their walls. Because she finds the topic so interesting, Erika is still research ing her question, long after she got an A on her project.

Barry’s team discovered that their town had been one of the most important crossroads when the stagecoach came daily. Digging deep into the records of property sales, they were able to chart how businesses, homes, and farms declined in value when the stagecoach left. In turn, the town’s population also declined.

Barry and his sister understood that many years had passed since the stagecoach stop had helped to make their town prosperous. However, they also thought evidence of their town’s past prosperity due to the increased stagecoach traffic might be an indicator for their town’s future prospects as well.

They transferred their data onto a graph. Then Barry’s sister took it to the town council to help make her argument that her idea for a new improved railway stop could improve her town’s future. She hoped that the lawmakers might make decisions for the future of their town and work to bring public transportation back. This move had the possibility of being both environmentally friendly and also economically beneficial for her town. Barry’s sister was using evidence from the past to try to improve the future.

Historians use statistics gathered during their research to draw conclusions regarding their compelling questions.

In this lesson, you’ve learned how social scientists investigate the past by using clues they find to form hypotheses.

Detectives Who Study the Past Social scientists include archaeologists who examine artifacts that people have made and left behind, historians who study the written records that people began to leave in the last few thousand years, or geographers who look at the natural and humanmade features of Earth.

Cave Art Caves have provided clues to the past for social scientists. Cave paintings and sculptures thousands of years old have been found all over the world. Artifacts also have been discovered in caves. The art and artifacts provide information about how people lived long ago.

Cave Art Tools Cave artists used sharp stones to grind colored minerals into powder. They mixed the powder with animal fat to create paint. They may have used moss, fur, hollow reeds, or their own hair as paintbrushes.

How to Study the Past Modern historians follow professional methods to arrive at a picture of the past that is as accurate as possible. They carefully select, weigh, and interpret the evidence available, taking care to avoid bias.

Planning Your Own Inquiry By following the steps of the inquiry process, students can learn more about how historians discover the past and use evidence to draw conclusions.

Classroom Activity

images of events in the ancient world. Research one key invention from the ancient world and present your ideas.

Video Activity Investigate the common themes of world history through a video covering the main ideas of the lesson and complete an online activity to show what you’ve learned.

Text with Notes Use your online or print Interactive Student Notebook to bring meaning to the reading you’ve completed.

In this lesson you will learn about the way we interpret civilizations that have existed in unique locations all across the globe. Each of these groups arose in different places and at differ ent times. But there are many common themes among them.

These similarities include the settlement of people based on geography and climate as well as the development of social structures. Also, you’ll learn about the birth of arts, architecture, writing, government, politics, and religion within these civiliza tions. You will also read about how webs of vast, complex trade routes connected these ancient peoples and brought them new ideas and products. Finally, you’ll discover how huge empires rose from rural and urban societies as well as why they failed.

Of course, world history is more than the rise and fall of civilizations. It’s also about the themes that we find in each of the civilizations. In addition, they might share similar characteristics or traits. How people interact with their environment, how and what they believe, and the way they govern all come from somewhere in the past in some way. Learning the ways that people once lived helps us understand the themes of our own world and time because many of these ancient ways still exist.

While studying history, you’ll learn about each of these civilizations based on their location in the world. But first, let’s explore them based on their common themes. Keep these pat terns in mind as you explore the wonders of the ancient world.

These obelisks at Aksum in present-day Ethiopia were probably built in the 4th century c.e. An ancient practice in the region was to build obelisks to mark burial sites.

Social Studies

Vocabulary

gender roles kinship pastoral nomad

Civilizations and kingdoms that arose in ancient Egypt demonstrate each of the six key themes.

Historians use themes to identify patterns in history. Many possible themes can apply to historical events. Two broad themes are continuity and change, that is, the way things have stayed the same or changed over time. Two other broad themes are integra tion and difference. Integration refers to ways in which the peoples of the world have been drawn together by historical factors. Difference concerns how they have remained distinct and diverse.

Historians often highlight six themes in world history: human-environment interaction, rise of civilizations, growth and changes in societies, development of political institutions and ideas, belief systems, and interconnectedness of societies. Studying history with these themes in mind will help you make connections among events and interpret the past.

Human-Environment Interaction The interaction between humans and the environment is the first theme. The environment has been a key factor in human activity throughout history. It has affected how and where people live and how they support themselves. At the same time, human actions have also changed the environment in many ways. This theme covers topics such as disease, population growth, migration, and patterns of human settlement.

The way in which civilizations rose is another important theme. As early humans learned the advantages of cooperating with one another, they began to form communities and societies across the ancient world. Many of these communities developed into early cities called city-states, and eventually formed civilizations. Not all civilizations devel oped in the same way, however. Some civilizations developed writing but a few did not. Even between similar civilizations, there were major differences. For example, some built massive cities with trade networks. Others had complex trade networks, but without large or fully permanent cities. Today, evidence remains of the success of these civilizations.

This theme covers a wide range of topics. Some examples are:

• the development of trade networks

• the improvement of the written language

• artistic and architectural advancements

• the unification of smaller states

• the prominence of patriarchal societies

The organization of societies is also a key theme. In prehistoric times, people formed social groups to meet their need for food, shelter, and security. Over time, social groups banded together to form societies. Although social structures varied from culture to culture, they also had many things in common. By examining and comparing these structures, we can get a better understanding of human life.

Among the topics covered by this theme are gender roles and relations, including the place of women in society. Other topics include customs relating to family and kinship, racial and ethnic differences and their impact on society, and divisions of social and economic class.

Another key theme is the creation of political systems and forms of government. World history has often been presented as a series of one ruler or government after another. It is much more than that. Nevertheless, political structures are an important aspect of history and a key element in the growth of civiliza tion. Some civilizations have favored complex governments and systems, while others might prefer less complex ways of organizing society. The way in which people have organized and governed themselves says a great deal about human society.

Various topics fall under the theme of development of politi cal institutions and ideas. Forms of government, how city-states and civilizations grow, and the ways political revolts and revolu tions happen are examples of these topics.

gender roles customs relating to the position of men and women in society

kinship family relationship, either by birth, marriage, or adoption

Belief Systems

An additional key theme is the creation and development of belief systems. As ideas continued to develop throughout the ancient world, new philosophies and religions began to emerge. These belief systems often brought great social and political change

A number of topics fall under the theme of belief systems. Here are some examples:

• the perseverance of Jews under Roman persecution

• social changes in India as Hinduism gained followers

• the cultural impact Buddhism had on Indian empires

• the impact of three philosophies on Chinese societies and order

• the birth of Jesus Christ and his effect on ancient cultures

• the spread of Islam and its impact on the world

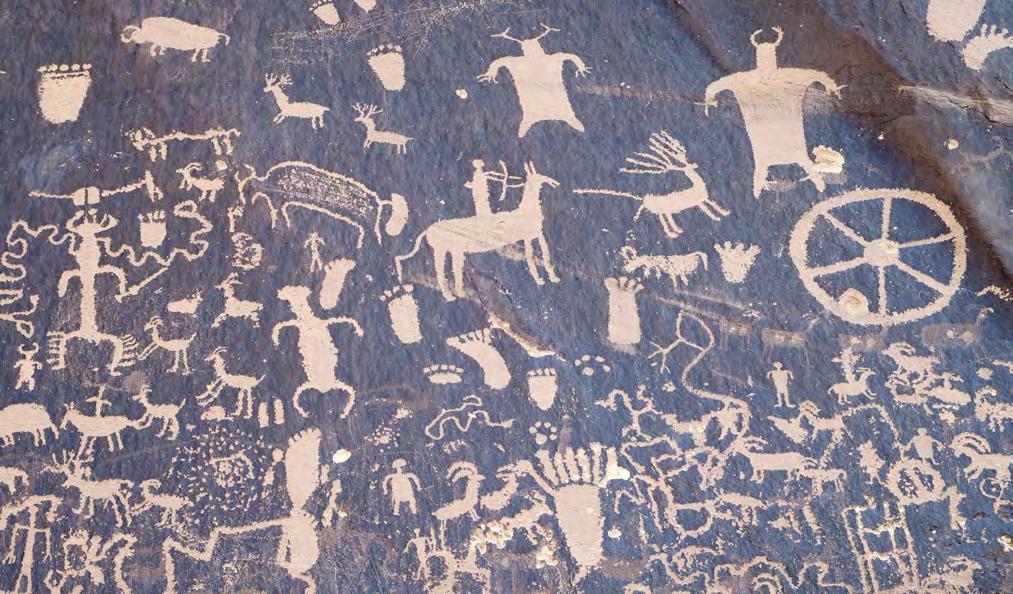

Cave paintings, or carvings like this one, reveal interesting details about ancient peoples as well as their inventions and cultures. This carving from Newspaper Rock in present-day Utah shows ancient Indigenous art.

The last theme you’ll learn about is the interconnectedness of societies. The new ideas, products, and advancements that were developed in one part of the ancient world eventually reached other parts of it. Large networks of trade routes throughout the world connected the groups you’ll learn about, resulting in the combining of cultures.

Various topics fall under the theme of interconnectedness of societies. Some examples are:

• the exchange of inventions and products

• the spread of religions and arts

• the migration of people to new locations

• the practice of diplomacy among societies

About 25 million years ago, a primate group called the Great Ape family split into apes and monkeys. Both groups thrived in trees, but they had some differences between them. While apes used their arms for locomotion by swinging in trees, monkeys primarily used their four legs for travel. As apes developed strong vision, monkeys developed a better sense of smell. Apes later split up into two other groups: today’s apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas) and hominins. Some of these hominins went on to become modern humans.

Even though there are many ideas regarding the evolution of these hominins, many scholars agree that hominins of the Homo genus developed about 2.5 million years ago. Like our closest non-hominin relative the chimpanzees, Homo sapiens walked on two feet at least some of the time and appeared around 6 million years ago. Eventually they evolved and could walk upright.

Evolution of Homo sapiens outpaced the other hominin groups about 70,000 years ago as its brain growth continued, which required larger food intake. These larger brains made great social and technological advances such as pair-bonding, sharing of knowledge and technical skill, the ability to imagine and plan, and the creation of cultures and myths. Pair-bonding, or having a single mate, allowed for more extensive child rearing and contributed to survival success.

The ability of early humans to adapt to their environments proved crucial to their survival when Africa’s climate got worse about 160,000 years ago, making it unlivable. Many of our early ancestors died during this time, but others migrated to the southern coast where they found food and resources. The larger brains of early humans also let them talk and work with one another. The cognitive, social, and technological advances of these early humans allowed them to better exploit and defend their territories. For these early humans, territory that was rich in natural resources was worth defending from invaders because access to resources led to increased probability of survival.

Early humans moved across the Earth and most continents about two million years ago, driven by population gains and increased competition for food. Additionally, they began to farm, which led to new inventions and innovations. These included the herding of animals, smelting of metals, the plough, twisted rope, musical instruments, religious worship, and complex boats. Earlier breakthroughs were the discovery of fire, cooking, and development of tools. With these discoveries and farming, larger communities and complex urban societies grew.

As you read on, consider these questions:

• Why did some humans start to plan and harvest crops?

• Why did some humans live in crowded villages and later build cities?

• Why did later humans accept the rule of monarchs, or kings and queens, and pay taxes?

• Why did the pace of historical change in certain parts of the world begin to speed up?

Eventually, prehistoric humans began building structures. These structures became more permanent and complex as farming increased, which led to the creation of villages and towns.

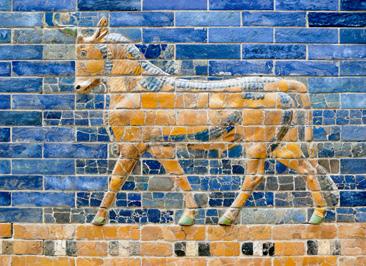

Ancient Babylonian architecture remains notable for its designs. This reconstructed detail of a city wall can be seen today in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

As civilizations rose and interacted, technical and intellectual innovations occurred. Many of these advances appeared in dense agricultural areas like the Nile River valley of Africa, Indus River valley civilizations of India, the lands around the Aegean Sea, and China. Advances also occurred in rural areas of the Middle East like Mesopotamia, Syria, Anatolia, and Persia. Around 2000 b.c.e., civilizations that rose in the Americas like the Olmec in Mesoamerica and the Chavín in South America also added to this kind of development.

The inventions and ideas created between 4000 and 1000 b.c.e. were very important for further development. These included the wheel, writing, complex metallurgy (metal working), codes of law, mathematics, and astronomy.

New ideas about social structures also occurred during this time. As the global population grew, powerful leaders rose up and combined smaller tribes into larger city-states with governments. These city-states were often ruled by kings, and sometimes queens, who said gods gave them power that could be passed down throughout their family.

With the support of political elites, these rulers taxed people from both cities and rural areas to pay for bureaucracies, armies, irrigation works, and architecture. Writing was further improved to record the actions of these governments and leaders. This allowed for ideas about governments, religion, science, and literature to be shared with others over larger distances. In addition, early writings from Hinduism and Judaism set the stage for some later religions.

As city-states kept growing, some farmers migrated into more rural areas of Africa, Southeast Asia, North and South America, and Europe. They also moved to the steppes of Central Asia to start a new way of farm life. There, people called pastoral nomads lived off the livestock they herded and often came into their local city-state to trade. Pastoral nomadism allowed humans to adapt to climate in large numbers by relocating when farmland was poor and to graze their herds over vast areas.

Sometimes wars broke out between urban and rural societ ies, which often gave the city-states power over farmers. These warring societies were sometimes ruled by monarchies that had vastly expanded their control over agricultural regions. Those who were not ruled by these monarchies may have remained in small villages or lived as hunter-gatherers or pastoral nomads.

pastoral nomad a person who migrates and depends on the livestock they raise

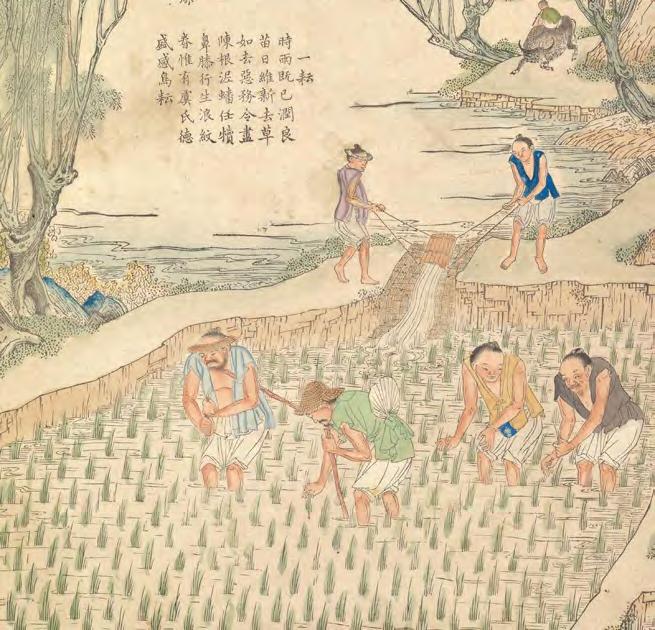

The Chinese made many inventions that improved agricultural methods for farming.

The Pantheon was built during the Roman Empire, one of the largest empires to ever exist. Originally a pagan temple, the Pantheon was converted into a Christian church.

1000 b.c.e.–300 c.e.

As the number of cities grew, a new and larger form of state developed: the empire. During this age of empires, the same patterns of change from the previous era continued—but at an accelerated rate. These complex new empires became much more efficient at controlling people’s lives and habits and gathering taxes.

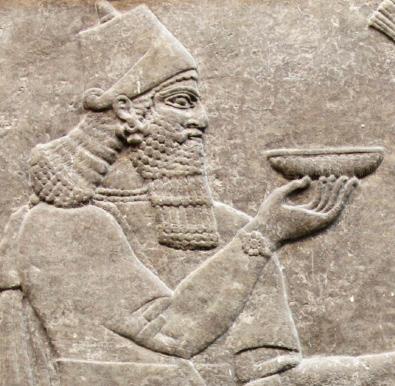

There were many large empires in the ancient world. In Mesopotamia, the Assyrian and Babylonian empires thrived. Persia was home to the Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sasanian empires. The Kushan Empire in Central Asia, the Maurya Empire in India, and the kingdom of Kush in the upper Nile River valley each made unique contributions to the ancient world and its people.

The largest empires were the Roman Empire and the Chinese Han Empire. At one point, the Romans controlled the entire Mediterranean Sea area and much of Europe. While they did not rule a large part of the Earth’s land, these two empires accounted for about half of the world’s people.

The goods and ideas that were created within all of these empires soon interacted. The Silk Road’s land and sea routes created a huge web of trade routes that connected empires across the Eastern Hemisphere. Similar routes existed in Mesoamerica and along South America’s Andean mountain range in the Western Hemisphere.

Along the Silk Road, merchants traveled long distances to get to their rural and urban destinations. The Silk Road allowed the trade of goods and ideas, which is how religions from across the globe were able to reach different peoples. Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Greek thought, and the philosophy of Confucianism were all spread along this route and changed based on the social orders within each society.

The land and sea routes of the Silk Road played a critical role in fostering cultural diffusion among various empires of the ancient world.

The creation of metal money also helped interactions among ancient peoples. After spreading throughout the ancient world around the 6th or 5th century b.c.e., metal money was used in Greece, Egypt, Persia, Phoenicia, Carthage, India, China, and Rome.

In the 300s c.e., the Romans were facing trouble. By 476, the Western Roman Empire collapsed and a number of small kingdoms took its place. At the same time, Christianity spread rapidly across Europe. The Eastern Roman Empire survived as the Byzantine Empire until 1453. For centuries, Western Europe would become locked in decline and struggle with itself and its neighbors.

Some of those neighbors included Arabs, who began to spread Islam from the Middle East across North Africa and into Spain in the 600s. It eventually arrived in Asia. The rise of Islam created some conflict with other religions. However, it also led to a golden age throughout the Islamic world. Later thinkers would use the discoveries uncovered or rediscovered by Islamic artists, scientists, and writers.

This carving at Dazu in China was created during the Song dynasty. It shows a remarkable combination of Buddhist, Confucian, and Daoist styles and figures.

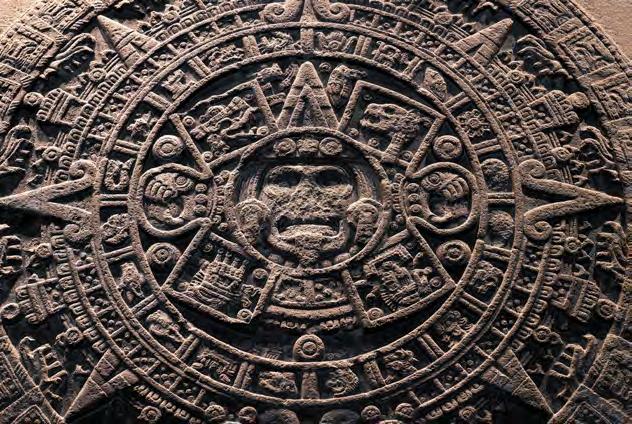

The Aztecs created long-lasting works of art and had a thriving culture. This calendar stone was excavated in Mexico City.

Around the same time, other areas were also experiencing growth. The Tang and Song dynasties in China restored the Han style of government, engaged in trade, and made significant cultural developments. In Africa, the empires of Mali and Ghana developed trade and complex economies. Islam was adopted throughout West Africa, and Arabic became widely used in some areas.

As civilizations across the world continued to develop, Europe experienced its own renaissance in the 15th to 16th centuries. European thinkers made significant developments in science and art. Europeans then set out to shorten trade routes with China and India. Their desire to explore led to their encounters with Indigenous people of the Americas beginning in the 15th century.

Some Indigenous civilizations of North and South America had built cities with monuments and complex societies. Although they did not have highly developed writing systems, powerful groups like the Aztec and Inca built complex systems, cities, and advanced infrastructure to help their populations survive and grow.

However, many of these groups faced disease, starvation, war, and enslavement after Europeans arrived. The desire by European countries to build new colonies in these lands also resulted in Africans being enslaved and sent to the Americas.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Europeans began developing new ideas about government, society, and science. This period is known as the Enlightenment, a time when thought and society became more secular, or non-religious.

The major changes that took place across the world from 300 to 1750 c.e. were not just isolated to each region. Over time, they spread to other places around the entire globe. This period was notable for how places exchanged ideas and goods through trade. However, it was also marked by the spread of devastating war and enslavement across continents. Along with the development of the Enlightenment, these events, ideas, and other ways of understanding the past continue to have an impact around the world today.

Six themes for analyzing world history are human-environment interaction, rise of civilizations, growth and changes in societies, development of political institutions and ideas, belief systems, and interconnectedness of societies.

Beginnings to 4000 b.c.e. Hominins adapted to their environments and created inventions that helped them survive. Modern humans evolved from a hominin group called Homo sapiens. After humans discovered how to farm, communities and civilizations began to emerge.

Kingdoms and Innovations: 4000 b.c.e.–1000 b.c.e. As cities grew, kings took power and taxed the kingdom’s people to pay for certain public works. During this time, many important inventions were created and writing was heavily improved.

An Age of Empires and Interactions: 1000 b.c.e.–300 c.e. A ll across the ancient world, power ful empires rose from cities. These empires interacted along a web of trade routes. Both goods and ideas were shared along the trade routes connecting these places.

A World of Changes: 300–1750 c.e. Though some areas declined, others grew at a more rapid pace. The expansion of trade, culture, science, and even violence spread across oceans and continents through the centuries.

The ancient Greeks built the Parthenon and dedicated it to their goddess Athena. The ancient Greeks are famous for their religion, government, and Olympic games.

Gather evidence by studying these sources—along with the other sources listed in the Unit Inquiry Project—as you prepare to write an argument answering the unit’s compelling question.

Knowing how to access, evaluate, and analyze materials available in your school’s library or media center is a key skill. Here are some ideas to help you navigate the resources that are available to you.

1. Carefully review the assignment and define your research topic. The important thing at the start of your research is to know exactly what you’re expected to do. In selecting topics, you may want to begin by browsing in general works like a textbook or encyclopedia. These sources will help you identify topics for which a lot of information is available.

2. Identify many possible sources. Spend some time browsing in the database or identifying books that might be helpful. Remember that you may find your topic in books about a broader subject. Using the internet will also help in your search. Bookmark the most promising sites to refer back to.

3. Identify the best sources. Once you’ve listed possible sources, select those that will best help with your research task. Use newer books and articles when possible. Generally, newer sources are more likely than older ones to reflect current research. Of course, this does not apply to primary sources.

4. Gather information from your sources. Once you have identified your sources, it is time to compile the information you need. Be sure to go back to the project requirements as you gather information. Think of these two questions: (1) Which pieces of information will help you complete the research task? (2) What is the best way to organize the information? Also write down bibliography information as you research. This will save time at the end of your project.

5. Create the product. Keep in mind who your audience is. Strive to create a product that meets the needs of the audience. Add visuals such as pictures, graphs, maps, timelines, and artifacts to add interest to your presentation.

6. Reflect on what you have done. When your project is complete, stop and reflect. What did you learn about researching a topic and presenting the results? What went well? How would you tackle the same task in the future? What would you do differently?

There are many kinds of sources you can use. A primary source is direct or firsthand evidence about an event, person, or object. Primary sources can be speeches, letters, artifacts, and more. A secondary source describes, analyzes, and discusses a primary source. Secondary sources can be in books, articles, or newspapers. A secondary source can also contain a primary source. For example, a book that talks about Lincoln’s speech is a secondary source. The book could also have a copy of Lincoln’s speech inside.

When citing a book in a bibliography, follow the order: author, title of book, city of publication, publisher’s name, year of publication.

Example: Arburn, Michael. Learning History: An Adventure. New York: Random House, 2022.

When citing an article in a bibliography, follow the order: author, article title, magazine or newspaper, date of publication, page numbers of the article.

Example: Adams, Steve. “Finding a Great Hotel in Paris.”

Travel Magazine, July 2023: 38–42.

The internet is an amazing research tool. However, it’s important to remember that anybody can create a website and post information on it. Some sites are reliable. Others are not. Here are some ideas on picking the best sites.

When evaluating websites, think about three questions:

1. Is the information from a reliable source?

• Ideally, you are looking for information from an expert source. An expert source is an authority on the subject you are researching.

• Websites that end in .gov are related to government bodies. The information found on these sites can be some of the most reliable on the internet.

• Websites that end in .edu are related to a school or college and can be very reliable, since they are often created by researchers or scholars. On the other hand, schools may allow or encourage all students to post information on a school-related website. Such material may or may not be accurate. Try to identify the qualifications of the author before you use the information.

2. Is the information biased?

• A source is biased if the author has a certain opinion or prejudice that he or she wants to promote. It is very important to develop the ability to detect bias.

• Social scientists call research that is free of bias “objective.” For most research projects, you will want to find objective information. If the author is careful to separate opinion from facts, your job is easier. Be on the lookout for opinions that are disguised as facts.

• Ask yourself what person or organization prepared the information. Why did they post it on the internet? What is their purpose? Are they trying to convince you of something?

3. Is the information accurate?

• To find this out, ask yourself these questions: Is the information repeated on other sites or in other sources you are using? Is the information based on recent research, or is it old and possibly outdated? Does the writer reveal where he or she got the information? (Those who do not reveal their sources may not want their sources checked. This can be a sign of bad scholarship.)

Have you ever put together a jigsaw puzzle? You start with a picture that shows what the completed puzzle will look like. Then you fit the pieces together until they make up that picture.

Suppose, though, that you didn’t have a picture to work with, but only the pieces? Even worse, what if most of the pieces were missing? How hard would the puzzle be then?

That’s the situation facing anthropologists who study early hominins. These social scientists are trying to understand how and when early hominins developed. The puzzle pieces they work with are bits of bone that are millions of years old. Anthropologists know that they have only some of the pieces. Each new find gives them another clue to work with.

Gradually, the overall shape of the picture becomes a bit clearer. For instance, scientists today agree that hominins first appeared in Africa. But only 60 years ago, even this much of the picture was unclear. It took many finds to discover that Africa was the birthplace of early hominins.

Each of these finds was the result of hard, patient work. Here you will learn about some other important pieces of the hominin puzzle—and the people who found them.

In 1924, an anthropologist named Raymond Dart examined an ancient skull that had been found in a quarry in Taung, South Africa. The skull belonged to a young, apelike creature. It became known as the Taung Child. Dart gave the fossil a more scientific name: Australopithecus africanus. This name is Latin for “southern ape from Africa.”

The Taung Child was the first Australopithecus fossil ever found. It is 2 to 3 million years old. Dart was thrilled by the discovery. He thought it showed that the earliest hominins appeared in Africa. Other scientists disagreed. At that time, many of them believed that hominins first appeared in Asia. Over the next 20 years, a Scottish anthropologist, Robert Broom, collected more and more Australopithecus fossils in Africa. By the 1940s, most scientists had to agree that Dart was right.

Far to the north, Mary Leakey found more puzzle pieces at Olduvai Gorge in modern-day Tanzania. Mary and her husband, Louis, had spent 30 years searching the gorge for hominin remains. In 1959, Mary found hundreds of bits of bone. When she pieced them together, they made up the skull of a previously unknown type of hominin. The fossil was nicknamed Nutcracker Man for its large jaw. Today it is called Australopithecus boisei. It is more than 1.7 million years old.

More evidence was found by Mary and Louis’s son, Richard Leakey. Richard found his first fossil when he was just six years old—a part of an extinct pig. As a young man, he began leading expeditions in East Africa.

Richard made many important finds, including skulls and other bones of Homo habilis and Homo erectus. In 1970, he found another Nutcracker Man fossil.

Richard’s most famous discovery came in 1984, near Lake Turkana in Kenya. Most hominin fossils are small parts of the body. The new find was a nearly complete Homo erectus skeleton. Known as the Turkana Boy, it is about 1.6 million years old.

Richard’s wife, Meave, has also hunted fossils in Africa. Among her finds are still more species of early hominins. Richard and Meave’s daughter, Louise, has worked with Meave on field expeditions, continuing the proud Leakey tradition.

Mary Leakey made many finds during her long career. The one that excited her the most was a truly fantastic discovery: hominin footprints that were more than 3.5 million years old!

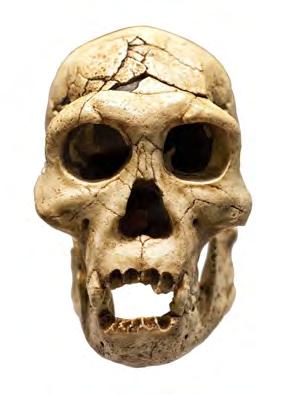

This ancient skull is a reconstruction of Homo erectus, the Upright Man.

Mary’s team spotted the footprints in 1976 at Laetoli in Tanzania. This site is about 30 miles south of Olduvai Gorge. The footprints were found in a layer of volcanic ash. Scientists think that a volcano erupted shortly after the footprints were made. When the ash hardened, it preserved the footprints.

Besides being amazingly old, the footprints were important for another reason. The creatures that made them had walked upright on two feet. The footprints were even older than the famous fossil nicknamed Lucy. They showed that hominins were walking upright at a very early date.

Tim White, an American anthropologist, helped excavate the Laetoli footprints. He also worked with Donald Johanson, who found Lucy. White’s own teams have made a number of other finds. One of them pushed hominin history even farther back in time.

In 1994, White was working in Ethiopia. An African member of his team discovered hominin fossils that proved to be 4.4 million years old. The fossils had a very ancient combination of apelike and humanlike features. White and his co-workers called the new species Ardipithecus ramidus. The word ramid means “root” in the Afar language of Ethiopia. The researchers thought that the fossil was very close to the root of the hominin family tree.