Student Edition

Lesson

compromises

Further:

Lesson

Constitution:

Perfect

has the Constitution created

more perfect Union”?

Primary

3

freedoms

Further:

of

Lesson 4

did the Federalist

the United States

Did Conflicts

American

Lesson 5

Republican visions

Sources:

Washington’s Cabinet

Affairs in the Young Nation

extent

the United States have

involved in world affairs in the early 1800s?

Lesson 6

it mean to be an American in the

1800s?

New Nation

Lesson 7

well did President Andrew Jackson

democracy?

Setting the Stage

Lesson 8

Manifest Destiny and the Growing Nation

justifiable was U.S. expansion in the 1800s?

Sources:

Inspired Americans to Move West?

Lesson 9

in the West

were the motives, hardships, and legacies

the groups that moved west in the 1800s?

Further:

Rush Pioneers

Lesson 10

Mexicano Contributions to the Southwest

have Mexicano contributions influenced life in the United States?

Further:

Culture

Lesson 11

An Era of Reform

To what extent did the reform movements of the mid-1800s improve life for Americans?

Investigating Primary Sources:

Were the Priorities for Education in the 19th Century?

Lesson 12

The Worlds of North and South

was life in the North different from life in the South?

Reading Further:

Mill Girls of Lowell

Lesson 13

African Americans in the Mid-1800s

How did African Americans face slavery and discrimination in the mid-1800s?

Reading Further: Harriet Tubman, Moses of the Underground Railroad 250

Which events of the mid-1800s kept the nation together and which events pulled it apart?

Primary Sources: How Did Slavery Create Tension Among the States Prior to the Civil War?

factors and events influenced the outcome of the Civil War?

Further:

House, Divided Families

To what extent did Reconstruction bring African Americans closer to full citizenship?

Further:

Long Road to Equal Rights

the Stage

Lesson 17

in the West

did settlers change the West and

American Indians?

Lesson 18

Rise of Industry

the benefits of industrialization

the costs?

Primary Sources:

Was Thomas Edison's Impact

Industrial

Lesson 19

The Great Wave of Immigration

was life like for immigrants in the

1900s?

Immigrants

Progressive Era

Lesson 21

United States

world affairs around the

22

trends

innovations

American

Culture

Lesson 23

did the Great Depression affect the United States?

Economy:

Economic

Setting the Stage

Lesson 24

World War II

What were the causes and consequences of World War II?

Reading Further:

United States on the World Stage:

and Cooperation

Lesson 25

The War Effort at Home

did World War II change the United States?

Further:

the Fight for Equality at Home

Lesson 26

The 1950s: Life After the War

Why are the 1950s remembered as an age of affluence?

Further: Rock and Roll Fever

Lesson 27

The Cold War

How did the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union shape the world in the decades after World War II?

Reading Further:

to the “Red Menace”: U.S.-Soviet Competition During the Cold War

Lesson 28

The Vietnam War

What made the Vietnam War difficult to win?

Primary Sources: What Lessons Emerged from the Vietnam War?

Setting the Stage

Lesson 29

The Civil Rights Movement

How did civil rights activists improve life for African Americans?

Further:

Indian

Lesson 30

American

The 1970s: A Period of Crisis and Change

should historians characterize the 1970s?

Primary Sources:

Is Watergate’s Most Important Legacy?

31

Life in the 1980s

How did the Reagan Revolution impact the nation?

Further:

Fight for Women’s Rights

Lesson 32

U.S. Domestic Politics at the Turn of the 21st Century

How have recent presidents tried to fulfill their domestic policy goals?

Further:

Role of Social Media in Politics

Lesson 33

U.S. Foreign Policy in a Global Age

How well have U.S. foreign policy decisions met the challenges

the global age?

United States in a Global Economy

Affairs

Growing Sense of

Jackson

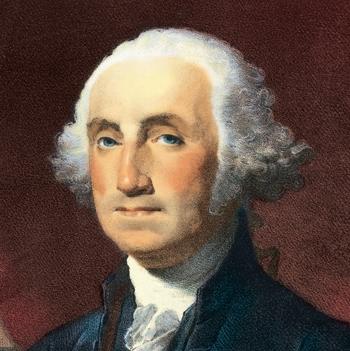

statue of George Washington stands before

columns of Federal Hall in New York City.

Washington was inaugurated as the na tion’s first president

years

of great change

1838, a total of 13 new

joined the original 13, as shown

nation’s first 50 years

Along with new states and territories came a steady increase in population, as the U.S. popula tion graph illustrates. Seven presidents served in office from 1789 to 1837, beginning with George Washington and ending with Andrew Jackson. Both men came to the presidency as military heroes—Washington from the American Revolution and Jackson from the War of 1812.

In this unit, you will learn about key events that occurred during the administrations of Washington through Jackson. Some of those events are listed below.

1789: George Washington takes the oath of of fice as the first president of the United States in New York City, the nation’s capital at the time.

1794: An army led by President Washington crushes the Whiskey Rebellion, an uprising by some frontier farmers who resisted paying certain taxes.

1800: John Adams, the nation’s second president, is the first president to live in Washington, D.C., the new capital city, in the still-unfinished White House.

1814: In a conflict between the United States and the United Kingdom known as the War of 1812, British forces capture Washington, D.C. The British burn the White House, the Capitol, and other government buildings.

During the War of 1812, U.S. forces turn back a British attack on Baltimore, Maryland. The Americans’ defense of Fort McHenry inspires Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner,” which later becomes the country’s national anthem.

1815: An American army led by General Andrew Jackson defeats the British in the Battle of New Orleans, which is the final battle of the War of 1812. The Battle of New Orleans is also the greatest U.S. victory of the war, and it makes Jackson a national hero.

1825: The Erie Canal opens. Begun in 1817, the canal creates a water route connecting Lake Erie and the Hudson River. Its success initiates a canal-building boom in the United States. You can locate the Erie Canal in the state of New York on the map Growth and Change in the United States, 1789-1839.

1828: Andrew Jackson of Tennessee is elected the nation’s seventh president. He is the first president to come from a state other than Vir ginia or Massachusetts.

1838–1839: Troops round up the remaining Cherokee in the East and move them west along a route that becomes known as the Trail of Tears. The Trail of Tears, shown on the map, is located in the southern United States.

After the American Revolution, leaders worked to guide the government formed under the Constitution. Look at the illustration of the four important leaders in the government. On the far right stands George Washington, who had been lured out of retirement to serve as the nation’s first president. Seldom has a leader seemed more reluctant to take power. “My movements to the chair of government,” he wrote on leaving home, “will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.”

Henry Knox sits opposite Washington. During the American Revolution, Henry Knox, a bookseller in Boston, became a general and Washington’s close friend and adviser. When Washington became president in 1789, he made Knox his secretary of war.

Two more important leaders in the early government were Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton, who stands beside the president, served as Washington’s secretary of the treasury. Jefferson, who stands behind Knox, served as secretary of state. He managed relations between the United States and other countries. Washington chose Hamilton and Jefferson for these positions because of all they had in common. Both were patriots who had served their country during the war. Both also had brilliant minds.

However, for all they had in common, the two men were opposites in many ways. Hamilton dressed with great care, while Jefferson was sloppy with clothes. Hamilton was a doer who moved from task to task, but Jefferson was a thinker who took time to explore ideas.

As you will discover, Hamilton and Jefferson soon became political rivals. Their conflicting visions about the role of government eventu ally gave rise to the nation’s first political parties and continue to influence America today.

George Washington meets with his close advisers, Henry Knox, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton.

Social Studies Vocabulary loose construction nullify sedition States’ Doctrine strict construction

Washington’s Farewell Address Whiskey Rebellion

Martha Washington, on the left, held tea parties on Friday evenings at the presidential mansion in New York City. At these parties, people could discuss important issues with President Washington, shown near the center.

On April 30, 1789, George Washington took the oath of office as the first president of the United States. After his inauguration, Washington addressed both houses of Congress and asked them to work with him to put into place “the wise measures on which the success of this government must depend.” At times, his hands shook so much that he had trouble reading his speech.

The Debate over Washington’s Title Washington had reason to be nervous because the first Congress was deeply divided. Some members were eager to build a strong national government, while others were just as eager to limit the power of the new government. These differences showed up immediately in a debate over what title to use when addressing the president.

Vice President John Adams pointed out that European heads of government had titles like “Your Excellency” that showed respect for their office. The president, he argued, should have a similar title. Supporters of a strong national government agreed.

Others argued that such titles smelled of royalty and had no place in a democracy. A few members of Congress joked that the rather plump Adams should be given the title “His Rotundity” (His Roundness). The debate finally ended when Washington let it be known that he preferred the simple title “Mr. President.”

Setting Up the Executive Branch Next, Congress turned to the task of creating executive departments. As Washington had feared, arguments broke out at once over what those departments should be and what powers they should have.

Congress eventually approved three departments. The Department of State was set up to handle relations with other countries. The Department of War was established to defend the nation. The Treasury Department was set up to oversee the nation’s finances. Congress also created an attorney general to serve as the president’s legal adviser and a postmaster general to head the postal system.

Washington chose men he trusted—such as Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and Henry Knox—to fill these positions as he often met with them to ask for their ideas and advice. The heads of the executive departments came to be known as the president’s cabinet.

The most critical problem facing the new government was that the national treasury was empty and the nation had no money. Congress had the power to raise funds through taxes, but its members argued endlessly about what to tax and by how much. In 1791, Congress finally agreed to place an excise tax, or a tax on the production or sale of a product, on whiskey and other luxury goods, such as carriages.

Settlers living west of the Appalachian Mountains reacted angrily to the tax. Because western farmers found it too costly to transport their grain across the mountains to sell in eastern cities, they distilled their bulky wheat into whiskey, which could be shipped more cheaply. Many farmers complained that the tax made their whiskey too expensive, so they refused to pay it.

To end these protests, Congress lowered the excise tax in 1793. Most farmers began to pay up, but not the tax rebels of western Pennsylvania. In 1794, these “Whiskey Boys” tarred and feathered tax collectors who tried to enforce the law.

Alexander Hamilton and George Washington saw the Whiskey Rebellion as a threat to the authority of the national government. At Hamilton’s urging, Washington led 13,000 state militia troops across the mountains to crush the rebels. Faced with overwhelming force, the rebellion ended.

Thomas Jefferson thought that the idea of sending an army to catch a few tax rebels was foolish. Even worse, he believed, was that Hamilton was prepared to violate people’s liberties by using armed force to put down opposition to government policies.

The French Revolution In 1789, the French people rebelled against their king, and Americans became caught up in a debate over the events in France. The leaders of the French Revolution dreamed of building a nation based on “liberty, equality, and fraternity [brotherhood].” Three years later, France became a republic and declared “a war of all peoples against all kings.”

Many Americans were thrilled by the French Revolution. This was especially true of Jefferson and his followers, who began calling themselves Democratic-Republicans, or simply Republicans. The Republicans saw the French Revolution as part of a great crusade for democracy.

The tax on whiskey upset many farmers west of the Appalachians. In western Pennsylvania, tax rebels tarred and feathered tax collectors who were responsible for enforcing the law. Washington and his army intervened to end the riots.

Whiskey Rebellion a revolt by farmers in 1794 against an excise tax on whiskey

When the French Revolution turned violent and thousands of nobles were beheaded on the guillotine, many Americans withdrew their support for the revolution.

In time, news from France caused supporters of the revolution to change their opinion. Cheered on by angry mobs, France’s revolution ary government began beheading wealthy nobles, resulting in some 20,000 men, women, and children being killed.

Hamilton and his followers, who called themselves Federalists, were appalled by the bloodshed, because many of them were wealthy. After hearing about the fate of wealthy families in France, they began to fear for their own safety, wondering whether such terrors could happen in the United States. “Behold France,” warned one Federalist, “an open hell . . . in which we see . . . perhaps our own future.”

Washington’s Farewell Address George Washington’s parting message to the nation, given in 1796, in which he warned of threats to the nation’s future

Washington’s Farewell Address

The growing division between Republicans and Federalists so disturbed Washington that he agreed to run for a second term as president in 1792. He was the only person, Hamilton and Jefferson told him, who could keep the nation together.

Near the end of his second term, Washington announced that he would not run again. Before leaving office, the president prepared a message that became known as Washington’s Farewell Address, in which he reminded Americans of all that bound them together as a people. “With slight shades of difference,” he said, “you have the same religion, manners, habits, and political principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together.”

Next, Washington warned of two threats to the nation’s future. One of those threats was problems the nation was having with other coun tries, and the other threat was the “spirit of party.” Washington said that it was natural for people to hold different opinions, but he warned against the dangers of passionate loyalty to parties. If fighting between parties was not controlled, it could tear the young nation apart.

Despite his worries for the future, Washington had much to be proud of as he left office. The new government was up and running, and the nation was growing so fast that it had added three new states: Kentucky, Tennessee, and Vermont. Most of all, Washington had steered his government safely through quarrelsome times, leaving the nation united and at peace.

George Washington’s warnings did not stop the rise of political parties in the young nation, however. The Federalist Party appeared first during the debates over the ratification of the Constitution. Its most influential leader was Washington’s energetic treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton.

Personal Background Hamilton was born in the West Indies and raised on the Caribbean island of St. Croix. When Hamilton was a teenager, he wrote a vivid description of a devastating hurricane that struck the island. The writing impressed all who read it, and a few St. Croix leaders arranged to send the talented teenager to New York, where he could get the education he deserved. Once in America, Hamilton never looked back.

Hamilton’s blue eyes were said to turn black when he was angry, but most of the time they sparkled with intelligence and energy. With no money or family connections to help him rise in the world, he made his way on ability, ambition, and charm.

George Washington spotted Hamilton’s talents early in the American Revolution and made the young man his aide-de-camp, or personal assistant. Near the end of the war, Hamilton improved his fortunes by marrying Elizabeth Schuyler, who came from one of New York’s richest and most powerful families. With her family’s political backing, Hamilton was elected to represent New York in Congress after the war. Later, he served as a delegate from New York to the Constitutional Convention.

View of Human Nature Hamilton’s view of human nature was shaped by his war time experiences. All too often, he had seen people put their own interests and desire for personal profit above the cause of patriotism and the needs of the country. “Every man ought to be supposed a knave [scoundrel],” he concluded, “and to have no other end [goal] in all his actions, but private interest.”

Most Federalists shared Hamilton’s view that people were basically selfish and out for themselves, so they distrusted any system of government that gave too much power to “the mob,” or the common people. Such a system, said Hamilton, could only lead to “error, confusion, and instability.”

American artist John Trumbull painted this portrait of Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton rose from poverty to lead the Federalist Party. His brilliant career was cut short when he was killed in a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr, whom he had accused of being a traitor.

Alexander Hamilton believed that to become strong, the United States needed to develop businesses such as this foundry in Connecticut. A foundry is a factory for melting and shaping metal.

Views on Government Federalists believed that “the best people”—educated, wealthy, public-spirited men like themselves— should run the country. Such people, they believed, had the time, education, and background to run the country wisely and could also be trusted to make decisions for the general good, not just for them selves. “Those who own the country,” said Federalist John Jay bluntly, “ought to govern it.”

Federalists favored a strong national government and hoped to use the new government’s powers under the Constitution to unite the quar reling states and keep order among the people. In their view, the rights of states were not nearly as important as national power and unity.

Hamilton agreed with this sentiment. Having grown up in the Caribbean, Hamilton had no deep loyalty to any state. His country was not New York, but the United States of America, and he hoped to see his adopted country become a great and powerful nation.

Hamilton’s dream of national greatness depended on the United States developing a strong economy. In 1790, the nation’s economy was still based mainly on agriculture. Hamilton wanted to expand the economy and increase the nation’s wealth by using the power of the federal government to promote business, manufacturing, trade, land grants for education, and infrastructure such as canals and roads.

Before this could happen, the new nation needed to begin paying off the huge debts that Congress and the states had accumulated during the American Revolution. In 1790, Hamilton presented Congress with a plan to pay off all war debts as quickly as possible. If the debts were not promptly paid, he warned, the government would lose respect both at home and abroad.

Hamilton’s plan for repaying the debts was opposed by many Americans, especially in the South. Most southern states had already paid their war debts and saw little reason to help states in the North pay off what they still owed.

To save his plan, Hamilton linked it to another issue: the location of the nation’s permanent capital. Both northerners and southerners wanted the capital to be located in their section of the country. Hamilton promised to support a location in the South if southerners would support his debt plan. The debt plan was passed, and the nation’s new capital—called the District of Columbia—was located in the South, on the Potomac River between Maryland and Virginia.

Hamilton asked Congress to establish the first national bank. The bank collected taxes, printed money, and made loans to businesses.

Next, Hamilton asked Congress to establish a national bank, which Hamilton believed would help the government by collecting taxes and keeping those funds safe. It would print paper money backed by the government, giving the nation a stable currency. Most important, the bank would make loans to businesspeople to build new factories and ships. As business and trade expanded, Hamilton argued, all Americans would be better off.

Once again, Hamilton’s proposal ran into heavy opposition. Where in the Constitution, his opponents asked, was Congress given the power to establish a bank? In their view, Congress could exercise only those powers specifically listed in the Constitution.

Hamilton, in contrast, supported a loose construction, or broad interpretation, of the Constitution. He pointed out that the Elastic Clause allowed Congress to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper” for carrying out its listed powers. Since collecting taxes was one of those powers, Congress could set up a bank to help the government with tax collection.

After much debate, Hamilton was able get his bank approved by Congress. Once established, in 1791, the Bank of the United States helped the nation’s economy grow and prosper.

Views on Great Britain and France When the French Revolu tion began, Hamilton hoped that it would lead to the “establishment of free and good government.” But as he watched it lead instead to chaos and bloodshed, his enthusiasm for the revolution cooled.

When war broke out between France and England in 1793, most Federalists sided with Great Britain. Some were merchants and shippers whose business depended on trade with America’s former enemy, while others simply felt more comfortable supporting orderly Great Britain against revolutionary France.

Hamilton favored Great Britain for yet another reason. Great Britain was all that he hoped the United States would become one day: a power ful and respected nation that could defend itself against any enemy.

loose construction a broad interpretation of the Constitution, meaning that Congress has powers beyond those specifically given in the Constitution

Thomas Jefferson was one of America’s greatest patriots. His strongest support came from the middle class: farmers, laborers, artisans, and shopkeepers.

Alexander Hamilton’s success in getting his plans through Congress alarmed Thomas Jefferson and his fellow Republicans. In Jefferson’s view, almost everything Hamilton did in the name of putting the United States on the path to greatness was instead a step down the road to ruin. The two men held very different views on almost everything.

Personal Background Jefferson was born in Virginia to an old and respected family. One of ten children, he was gifted with many talents, and as a boy, he learned to ride, hunt, sing, dance, and play the violin. Later in his life, Jefferson carried a violin with him in all of his travels.

Jefferson was also a gifted student and had already learned Greek and Latin by the time he entered college at age 16. He seemed to know something about almost everything and once wrote that “not a sprig of grass [is] uninteresting to me.” This curiosity would remain with him all his life.

With land inherited from his father, Jefferson set himself up as a Virginia tobacco planter. Like other planters, he used slaves to work his land.

Once he was established as a planter, Jefferson entered Virginia politics. Although Jefferson lacked the ability to make stir ring speeches as a politician, he did write eloquently with a pen. His words in the Declaration of Independence and other writings are still read and admired today.

View of Human Nature Jefferson’s view of human nature was much more hopeful than Hamilton’s. He assumed that informed citizens could make good deci sions for themselves and their country. “I have so much confidence in the good sense of man,” Jefferson wrote when revolution broke out in France, “that I am never afraid of the issue [outcome] where reason is left free to exert her force.”

Jefferson had great faith in the goodness and wisdom of people who worked the soil—farmers and planters like himself. “State a [problem] to a ploughman [farmer] and a professor,” he said, and “the former will decide it often better than the latter.”

Agriculture, according to Thomas Jefferson, was the most important part of the economy. He believed farming was the best occupation because it kept people out of corrupt cities.

Views on Government Republicans favored democracy over any other form of government and had no patience with the Federalists’ view that only the “best people” should rule. To Republicans, this view came dangerously close to monarchy, or rule by a king.

Republicans believed that the best government was the one that governed the least and that a small government with limited powers was most likely to leave the people alone to enjoy the blessings of liberty. To keep the national government small, they insisted on a strict construction, or interpretation, of the Constitution. The Constitution, they insisted, meant exactly what it said, no more and no less. Any addition to the powers listed in the document, such as the creation of a national bank, was unconstitutional and dangerous.

Along with advocating for a weak national government, Republicans favored strong state governments. State governments, they argued, were closer to the people, and the people could control them more easily. Strong state governments could also keep the national government from growing too powerful.

Views on the Economy Like most Americans in the 1790s, Jefferson was a country man. He believed that the nation’s future lay not with Federalist bankers and merchants in big cities, but with plain, Republican farmers. “Those who labor in the earth,” he wrote, “are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people.”

Republicans favored an economy based on agriculture and opposed any measures, such as the national bank, designed to encourage the growth of business and manufacturing. In their view, the national bank was not only unconstitutional, but against farmers. While the bank was happy to loan money to businesspeople to build factories and ships, it did not make loans to farmers to buy land.

strict construction a narrow interpretation of the Constitution, meaning that the Congress has only those powers specifically given in the Constitution

Edmond Genêt, the French representative to the United States, attempted to convince Americans to join the French in their war with Britain. After Genêt insulted President Washington, he was ordered to leave the country. Here, Secretary of State Jefferson presents Genêt to the president in 1793.

Another topic over which Republicans and Federalists had heated arguments was the French Revolution. Most Americans favored the revolution until it turned violent and led to war. As you have read, most Federalists then turned against the new French republic and sided with Great Britain. For this change of heart, a Republican newspaper called the Federalists “British bootlickers,” implying that they were weak and eager to please the British.

Despite the violence of the revolution, most Republicans continued to support France. While regretting the bloodshed, they argued that the loss of a few thousand aris tocrats was a small price to pay for freedom. For their loyalty to France, Republicans were scorned in a Federalist newspaper as “maneating, blood-drinking cannibals.”

In 1793, the French government sent Edmond Genêt (zhuh-NAY) to the United States as its new official representative. Genêt preferred to be called “Citizen Genêt,” a title that French revolutionaries adopted to emphasize the equality of all people. His mission was to convince Americans that they should join France in its war against Great Britain.

Republicans welcomed Citizen Genêt as a conquering hero. Large crowds cheered him as he traveled about the country, and in Philadelphia, the nation’s temporary capital, a great banquet was held in his honor.

When Genêt formally presented himself to President George Washington, he expected another warm and enthusiastic reception. Washington, however, did not want to be drawn into war with Great Britain, so his response to Genêt was cool and dignified.

Genêt began making speeches against the president. These attacks on Washington brought thousands of Genêt’s supporters into Philadelphia’s streets. “Day after day,” recalled Vice President John Adams, the protesters “threatened to drag Washington out of his house, and . . . compel [the government] to declare war in favor of the French revolution.”

This was too much, even for Jefferson. Calling Genêt “hot headed . . . disrespectful, and even indecent toward the President,” Secretary of State Jefferson asked the French government to recall its troublesome representative.

When the framers of the Constitution created the Electoral College, they imagined that the electors would simply choose the two best lead ers for president and vice president. That was how the nation’s first two presidential elections worked. By the third election in 1796, however, it was clear that political parties had become part of the election process.

The Republicans supported Thomas Jefferson for president. He had the support from many farmers in the South and West. The Federalists supported John Adams, who appealed to lawyers, merchants, ship owners, and businesspeople in the North. When the electoral votes were counted, John Adams was elected president by just three votes, and Jefferson came in second, making him vice president. The nation’s new top two leaders were political leaders from opposing parties.

The Alien and Sedition Acts President Adams tried to work closely with Jefferson at first, but Adams found that “party violence” made such efforts “useless.” Meanwhile, Federalists in Congress passed four controversial laws known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. They argued that these laws were needed as protection against foreign ers who might threaten the nation. However, the real purpose of the Alien and Sedition Acts was to make life difficult for the Federalists’ rivals, the Republicans.

Three of the laws, the Alien Acts, were aimed at aliens, or noncitizens. The first law lengthened the time it took for an immigrant to become a citizen with the right to vote—from 5 to 14 years. Since most immi grants voted Republican, Jefferson saw this law as an attack on his party. The other two Alien Acts allowed the president to either jail or deport aliens who were suspected of activities that threatened the government. Although these laws were never enforced, they did frighten a number of French spies and troublemakers, who then left the country.

The fourth law, known as the Sedition Act, made sedition—encouraging rebellion against the government—a crime. Its definition of sedition included “printing, uttering, or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious [hateful] writing” against the government, Congress, or the president. Alexander Hamilton approved of this law, believing that it would punish only those who published lies intended to destroy the government.

Instead, the Sedition Act was used to punish Republican newspaper editors who insulted President Adams in print. One, for example, called him “old, querulous [whiny], bald, blind, crippled, toothless Adams.” Twenty-five people were arrested under the new law, ten of whom were convicted of printing seditious opinions.

sedition the crime of encouraging rebellion against the government

John Adams, a Federalist, was elected the second president of the United States by only 3 votes in the Electoral College. Thomas Jefferson, a DemocraticRepublican who had 68 votes to Adams’s 71, became vice president.

nullify to refuse to recognize a federal law. This action by a state is called nullification.

States’ Doctrine the theory that rights not specifically given to the federal government by the Constitution remain with the states

In 1800, the federal government found a new home in Washington, D.C. Here, Pennsylvania Avenue stretches across the west end of the Capital grounds.

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions

Republicans viewed the Sedition Act as an attack on the rights of free speech and free press. Since the federal government was enforcing the act, Republicans looked to the states to protect these freedoms.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison drew up a set of resolutions, or statements, opposing the Alien and Sedition Acts and sent them to state legislatures for approval. They argued that Congress had gone beyond the Constitution in passing these acts. States, therefore, had a duty to nullify the laws—that is, to declare them to be without legal force.

Only two states, Virginia and Kentucky, adopted the resolutions. The arguments put forward in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were based on the States’ Doctrine of the Constitution. This theory holds that rights not specifically given to the federal government remain with the states. Of these, one of the most important is the right to judge whether the federal government is using its powers properly.

When no other states approved the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, the protest died. The States’ Doctrine, however, was not forgotten, and it would be raised and tested again in the years ahead.

The New National Capital

In 1800, the federal government moved to the city of Washington in the District of Columbia. Most of the gov ernment’s buildings were still under construction. President Adams’s wife, Abigail, described the new “President’s House” as a “castle” in which “not one room or chamber is finished,” and she used the large East Room for hanging laundry, as it was not fit for anything else.

The move to Washington, D.C., came in the middle of the 1800 presidential election. Once again, Republican leaders supported Thomas Jefferson for president and hoped to avoid the strange outcome of the last election by choosing a New York politician named Aaron Burr to run as his vice president.

The Federalists chose John Adams to run for reelection as president, while Charles Pinckney of South Carolina was selected to run for vice president. Some Federalists would have preferred Alexander Hamilton as their presidential candidate. Although he did not run, Hamilton’s influence would shape the results of the election.

The Campaign The candidates outlined their campaign issues early. Jefferson supported the Constitution and states’ rights and promised to run a “frugal and simple” government. Adams ran on his record of peace and prosperity.

The campaign, however, centered more on insults than on issues. Republican newspapers attacked Adams as a tyrant, even accusing him of wanting to turn the nation into a monarchy so that his children could follow him on the presidential throne.

Some Federalist newspapers called Jefferson an atheist, or someone who denies the existence of God. Jefferson, these newspa pers charged, would “destroy religion, introduce immorality, and loosen all the bonds of society.” Frightened by these charges, some elderly Federalists buried their Bibles to keep them safe from the “godless” Republicans.

The Divided Federalists Hamilton and his followers refused to support Adams because of disagreements over the president’s foreign policy. “We shall never find ourselves in the straight road of Federalism while Mr. Adams is President,” stated Oliver Wolcott, one of Hamilton’s close allies.

As the campaign heated up, Hamilton worked feverishly behind the scenes to convince the men chosen for the Electoral College to cast their presidential ballots for Pinckney over Adams. Pinckney seemed more likely than Adams to value Hamilton’s advice and his firm Federalist principles. With Pinckney as president, Hamilton believed that he would be able to personally guide the United States into the new century.

This Republican presidential campaign banner is from 1800. The banner reads, “T. Jefferson President of the United States of America. John Adams no MORE.”

Here, Republican women help Thomas Jefferson win the election in New Jersey in 1800. Women were allowed to vote in New Jersey until 1808.

When the Electoral College voted early in 1801, it was clear that John Adams had lost the election. But to whom? Under the Constitution, each elector cast two votes, with the idea that the candidate finishing second would be vice president. All of the Republican electors voted for Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, and the result was a tie between them.

Breaking the Tie In the case of a tie, the Constitution sends the elec tion to the House of Representatives, where each state has one vote. Burr could have told his supporters in the House to elect Jefferson president, as his party wanted, but he instead remained silent, hoping the election might go his way. When the House voted, the result was another tie.

In the presidential election of 1800, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr received the same number of electoral votes, and after almost a week of deadlock in the House of Representatives, Jefferson was elected president. The Twelfth Amendment was ratified in 1804 to prevent such ties in the future.

Thomas

After 6 days and 35 ballots, it was Federalist Alexander Hamilton who broke the deadlock. He asked his supporters in the House to vote for Jefferson, because of the two Republicans, he said, “Jefferson is to be preferred. He is by far not so dangerous a man.” The tie was broken, and Jefferson was elected president.

In 1804, the Twelfth Amendment was added to the Constitution to prevent such ties. The amendment calls for the Electoral College to cast separate ballots for president and vice president. If no presi dential candidate receives a majority of electoral votes, the House of Representatives chooses a president from the top three candidates. If no candidate for vice president receives a majority, the Senate chooses the vice president.

A Peaceful Revolution

The election of 1800 was a victory for Jefferson and his Republican Party, but it was also a victory for the new system of government established by the Constitution. In other countries, power changed hands by means of war or revolution. In the United States, power had passed from one group to another without a single shot being fired.

In this lesson, you read about the beginnings of political parties in the United States.

The New Government Under Washington George Washington took office as president in 1789. In 1794, he ended the Whiskey Rebellion, a farmers’ protest against taxes.

Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists Hamilton and the Federalists favored a strong national government. They supported a loose construction of the Constitution. They also favored using the government’s power to support business, manufacturing, and trade. Alarmed by the violence of the French Revolution, the Federalists favored Great Britain in its war with France.

Thomas Jefferson and the Republicans Jefferson and the Republicans championed states’ rights and an economy based on agriculture. They supported a strict construction of the Constitution. Republicans saw the French Revolution as a step toward democracy and attacked the Federalists’ support for Great Britain.

The Presidency of John Adams During Adams’s presidency, Federalists used the Alien and Sedition Acts to attack Republicans. In response, Republicans urged states to nullify these laws.

The Election of 1800 and the Twelfth Amendment Adams lost the election of 1800 to Thomas Jefferson after the Federalists broke a tie vote between Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The election was sent to the House of Representatives, and after days of deadlock, Jefferson was eventually elected president. In 1804, the Twelfth Amendment was added to the Constitution to prevent such ties.

.

George Washington succeeded in launching the new nation, but two of his closest advisers held opposing viewpoints about government. Read these primary sources and do research of your own to make and support a claim about how disagreements within Washington’s cabinet affected American politics.

One of the debates among Washington’s advisers concerned the repayment of U.S. debts from the American Revolution. Alexander Hamilton believed that all the states should pool their combined debt and pay it back together, but Thomas Jefferson instead wanted to limit the government’s ability to borrow money. Historians have pointed out that two very different philosophies about government underscored this disagreement. Hamilton’s Federalist ideas favored a strong central government, a national bank, and an emphasis on manufacturing. Jefferson’s Republican philosophy favored a smaller national govern ment, stronger states, and favoritism to agricultural interests.

In this letter to Washington, Jefferson argues against Hamilton’s debt plan and warns of a rising monarchy. After reading the letter, do you believe Jefferson is interested in compromising with the Federalists? Is this letter a reliable and neutral source for this conflict?

.

.

It has been urged then that a public debt, greater than we can possibly pay before other causes of adding new debt to it will occur, has been artificially created . it has furnished effectual means of corrupting such a portion of the legislature, as turns the balance between the honest voters which ever way it is directed . . . the ultimate object of all this is to prepare the way for a change, from the present republican form of government, to that of a monarchy of which the English constitution is to be the model . . .

The Antifederal champions are now strengthened in argument by the fulfilment of their predictions; that this has been brought about by the Monarchical federalists themselves, who, having been for the new government merely as a stepping stone to monarchy, have themselves adopted the very constructions of the constitution, of which, when advocating it’s acceptance before the tribunal of the people, they declared it insusceptible.

Although President Washington desperately hoped for a cooperative government, his cabinet passionately disagreed on important issues. In particular, Jefferson and Hamilton attacked one another’s political opin ions and personal lives. They took their arguments to public newspapers, although they often wrote under pseudonyms. For example, Hamilton used the name Phocion in an article in the Gazette of the United States

The president suspected an unavoidable rise of two separate politi cal parties, and consequently he desperately warned his advisers: “I do not see how the Reins of Government are to be managed, or how the Union of the States can be much longer preserved.” Read an excerpt from this letter written by Washington to Hamilton on August 26, 1792, in which he criticizes the behavior of his advisers. After reading the letter, describe what behavior Washington is warning against.

.

. . Differences in political opinions are as unavoidable as, to a certain point, they may perhaps be necessary; but it is to be regretted, exceedingly, that subjects cannot be discussed with temper on the one hand, or decisions submitted to without having the motives which led to them, improperly implicated on the other: and this regret borders on chagrin when we find that Men of abilities— zealous patriots—having the same general objects in view, and the same up-right intentions to prosecute them, will not exercise more charity in deciding on the opinions, & actions of one another. When matters get to such lengths, the natural inference is, that both sides have strained the cords beyond their bearing—and that a middle course would be found the best, until experience shall have pointed out the right mode—or, which is not to be expected, because it is denied to mortals—there shall be some infallible rule by which we could fore judge events . . .

How unfortunate would it be, if a fabric so goodly—erected under so many Providential circumstances—and in its first stages, having acquired such respectibility, should, from diversity of Sentiments, or internal obstructions to some of the acts of Government (for I cannot prevail on myself to believe that these measures are, as yet, the deliberate acts of a determined party) should be harrowing our vitals in such a manner as to have brought us to the verge of dissolution. Melancholy thought! But one, at the same time that it shows the consequences of diversified opinions, when pushed with too much tenacity; exhibits evidence also of the necessity of accommodation; and of the propriety of adopting such healing measures as will restore harmony to the discordant members of the Union, & the governing powers of it.

Just as Washington scolded Hamilton, he wrote similar repri manding letters to Jefferson. Washington continued to fear the public disagreements among his cabinet members and the rise of political parties. In fact, by the time Washington gave his Farewell Address in 1796, he warned against putting “in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party.”

Hamilton wrote this letter on September 9, 1792—before Wash ington’s Farewell Address. It is Hamilton’s response to Washington’s letter to him. Hamilton tells Washington that Jefferson started the disagreement, while Hamilton himself suffered in silence until could hold back no longer. Read Hamilton’s letter and summarize what he intended to accomplish with it. Identify examples of how two political parties are rising in the United States. Who is the “differing member”? Is Hamilton’s letter a reliable source in evaluating this conflict?

Sir

I have the pleasure of your private letter of the 26th of August.

The feelings and views which are manifested in that letter are such as I expected would exist. And I most sincerely regret the causes of the uneasy sensations you experience. It is my most anxious wish, as far as may depend upon me, to smooth the path of your administration, and to render it prosperous and happy . . . I do not hesitate to say that in my opinion the period is not remote when the public good will require substitutes for the differing members of your administration. The continuance of a division there must destroy the energy of Government, which will be little enough with the strictest Union . . .

I know that I have been an object of uniform opposition from Mr. Jefferson, from the first moment of his coming to the City of New York to enter upon his present office. I know, from the most authentic sources, that I have been the frequent subject of the most unkind whispers . . . I have long seen a formed party in the Legislature, under his auspices, bent upon my subversion. I cannot doubt, from the evidence I possess, that the National Gazette was instituted by him for political purposes and that one leading object of it has been to render me and all the measures connected with my department as odious as possible . . .

Nevertheless I can truly say, that, except explanations to confidential friends, I never directly or indirectly retaliated or countenanced retaliation till very lately. I can even assure you, that I was instrumental in preventing a very severe and systematic attack upon Mr. Jefferson . . .

Despite George Washington’s efforts and recommendations, politi cal parties continued to represent differing opinions. The Federalist Party, represented by Hamilton and supported by Washington, dominated the administration of the government through the 1790s. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who both supported a smaller central government and more states’ rights, established the Democratic-Republican Party, which was also known as the Republican Party. Jefferson became the first Republican president in 1801, followed by Madison and James Monroe.

These two charts illustrate which party dominated the United States House of Representatives and Senate in the formative years of the nation. Describe the representation of the parties in the House and Senate from 1797 to 1799.

Find current primary sources that describe the percentages of political parties in the United States Congress today. Along with this information, examine news about current political leaders in the country. Determine if their personal lives are attacked in the media by one another and/or by media commentators. Are politicians still subjects to personal attacks in newspapers and television, and on the Internet? If so, how? How do these personal attacks affect the running of the government and the public’s participation in it?

Since the early days of the U.S. Congress, there have been two prominent political parties. From 1797 to 1799, there was nearly equal representation in the House of Representatives. Which party had more representatives in the Senate?

You

now examined how disagreements became evident in early America and in the current political world. Think about how disagreements in Washington’s cabinet affected politics in the early United States. Then compose and support an argument that explains how we still see the effects of Hamilton and Jefferson’s dispute

Did you know that you are carrying a history lesson in your pocket or wallet? You will find it on any $1 bill. Look at a dollar and see for yourself.

On one side, you will see two circles showing the Great Seal of the United States. For thousands of years, governments have used seals like this one to mark their approval of important documents. Our nation’s founders thought that a national seal was so important that they began work on it the same day they declared independence: July 4, 1776. In 1782, Congress approved the design we see on our currency today.

The Great Seal symbolizes the nation’s principles. For example, the unfinished pyramid on one side of the seal signifies strength and endurance, while the bald eagle on the other side is a symbol of the United States. In one claw, the eagle holds an olive branch, a symbol of peace, and in the other, the eagle holds arrows to symbolize war. The olive branch and arrows of war show that the United States will pursue peace but will also protect itself. Notice that the eagle faces peace.

When you turn the dollar bill over, you will see a portrait of George Washington. Americans still honor Washington as the nation’s first president, but few remember that Washington defined U.S. foreign policy in the early years of the nation’s history.

During his presidency, Washington established policies that would guide the United States in its future dealings with other nations. The United States could be actively involved in world affairs and risk war, or it could avoid involvement in other nations’ conflicts in the hope of staying at peace. Which choice would you have made for the new nation? In this lesson, you will read about four dilemmas that faced early U.S. presidents and how their decisions shaped the foreign policy pursued by later presidents.

The Great Seal of the United States’ imagery highlights the nation’s principles.

Social Studies

Vocabulary blockade embargo isolationism Monroe Doctrine neutrality

To what extent should the United States have become involved in world affairs in the early 1800s?

George Washington’s Farewell Address was published in newspapers in 1796. As part of his advice to the nation, he urged neutrality in foreign relations.

neutrality a policy of not choosing sides in a dispute or war between other countries

isolationism a policy of avoiding political or military agreements with other countries

When George Washington took office as the nation’s first president in 1789, the United States was weak militarily. The army that Washington had commanded during the American Revolution had disbanded and had not been replaced for two reasons. First, the government did not have the money to keep its army active. Second, some Americans feared that a standing national army could be used to take away their liberty. State militia troops, they believed, could handle any threats the country might face.

And there were indeed threats because the new nation was surrounded by unfriendly powers. To the north, the British controlled Canada and refused to abandon their forts in the Ohio Valley, even though this region now belonged to the United States. To the south and west, Spain controlled Florida and Louisiana.

Events in Europe also threatened the new nation. In 1789, the French people rose up against their king and fought to make France a republic. Some Americans were thrilled by the French Revolution. In 1793, however, France declared war against Great Britain, presenting President Washington with the difficult problem of deciding which side to take.

During its own revolution, the United States had signed a treaty of alliance with France in 1778. Alliances are agreements made with other nations to aid and support each other. In that treaty, the United States had promised to aid France in time of war, and many Americans were eager to honor that pledge, even if it meant going to war with Great Britain again.

Knowing that the United States was not prepared for war, Washington decided to ignore the treaty and announced a policy of neutrality. Under this policy, the United States would do nothing to aid either France or Great Britain in their war.

Before leaving office, Washington summed up his foreign policy in a farewell address to the nation. The United States, he said, could gain nothing by becoming involved in other nations’ affairs. “It is our true policy,” he declared, “to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” Washington’s policy of avoiding alliances with other countries became known as isolationism. For the next century, isolationism would be the foundation of U.S. foreign policy.

In this cartoon, American envoys meet with a French diplomat, depicted as a multiheaded monster holding a dagger. The cartoonist shared the negative view of French diplomacy held by most Americans in the 1790s.

Isolationism sounded good in theory, but it is often hard to stay out of other countries’ conflicts. No one knew this better than the nation’s second president John Adams, who tried to follow George Washington’s policy of neutrality. With France, however, staying neutral proved to be difficult.

After the outbreak of war between Great Britain and France in 1793, the British Navy began to attack U.S. merchant ships headed for France. French leaders hoped that these attacks, as well as Great Britain’s refusal to leave the Ohio Valley, would lead to war between Great Britain and the United States. However, those hopes were dashed when Washington sent John Jay, chief justice of the Supreme Court, to London to settle things with the British. In the treaty signed in 1794, known as the Jay Treaty, the British finally agreed to pull their troops from the Ohio Valley and halt attacks on U.S. shipping. France, still at war with Great Britain, viewed the Jay Treaty not only as a violation of its own treaty with the United States, made back in 1778, but as an alliance between the United States and Great Britain. In July 1796, the French navy began attacking U.S. merchant ships bound for Great Britain, and over the next year, French warships seized several American ships.

The XYZ Affair President Adams sent three envoys, or representa tives, to France to ask the French to end the attacks. French foreign minister Talleyrand refused to speak to the Americans. Instead, they were met by secret agents, later identified only as X, Y, and Z. The agents said that no peace talks would be held unless Talleyrand received a large sum of money as a tribute, or money given to someone in exchange for that person’s protection. Shocked by the request, the American envoys refused.

The XYZ Affair, as it became known, outraged Americans when the story reached home. At President Adams’s request, Congress voted to recruit an army and to build new ships for the nation’s tiny navy. The slogan “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute!” was heard everywhere as Americans prepared for war.

Meanwhile, Congress authorized U.S. warships and pri vately owned ships, called privateers, to launch a “half war” on the seas. During this undeclared war, American ships captured more than 80 French vessels.

As war fever mounted, President Adams, hardly a well-loved leader, found himself unexpectedly popular, and his Federalist Party gained support throughout the country. The question facing Adams was whether the popular thing—waging an undeclared war on France—was also the best thing for the country.

President John Adams believed that the United States needed a strong navy. Congress approved the construction of warships, including the Philadelphia , shown here under construction in 1800.

President John Adams knew that no matter how good war might be for the Federalist Party, it would not be good for the country. In February 1799, he announced that he was sending a group of men to France to work for peace, which likely infuriated Federalist leaders. Some accounts suggest they pleaded with the president to change his mind, but Adams would not budge.

By the time the peace mission reached France, a French military leader named Napoleon Bonaparte had taken over the French govern ment. Napoleon wanted to make peace with both Great Britain and the United States and ordered the navy to stop seizing American ships and to release captured American sailors.

In a treaty made between France and the United States in 1800, Napoleon agreed to end France’s 1778 alliance with the United States. In exchange, the Americans agreed not to ask France to pay for all the ships it had seized, which meant that the U.S. government would have to pay American ship owners for their lost property. To Adams, this seemed a small price to pay for peace with France.

Choosing the olive branch cost Adams political popularity. His pursuit of peace with France created strong disagreements within the Federalist Party, ultimately losing Adams and the Federalists votes when he ran for reelection in 1800. Jefferson defeated Adams in the election, and the Federalist Party lost much of its support. Over the next few years, Adams would watch his Federalist Party slowly fade away.

Still, Adams had no regrets. He wrote,

I will defend my missions to France, as long as I have an eye to direct my hand, or a finger to hold my pen . . . I desire no other inscription over my gravestone than: “Here lies John Adams, who took upon himself the responsibility of the peace with France in the year 1800.”

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Mediterranean Sea was filled with

Unfortunately, the peace that John Adams achieved with France did not last long. In 1803, France and Great Britain were again at war. As the conflict heated up, both nations began seizing American ships that were trading with their enemy. President Thomas Jefferson, who took office in 1801, complained bitterly that “England has become a den of pirates and France has become a den of thieves.” Still, like Washington and Adams before him, Jefferson tried to follow a policy of neutrality.

Impressment Remaining neutral when ships were being seized was hard enough. It became even harder when Great Britain began impress ing American sailors—kidnapping them and forcing them to serve in the British navy. The British claimed that the men they impressed were British deserters. This may have been true in some cases, as some sailors may well have fled the terrible conditions on British ships, but thousands of unlucky Americans were also impressed.

American anger over impressment peaked in 1807 after a British warship, the Leopard, stopped a U.S. warship, the Chesapeake, to search for deserters. When the Chesapeake’s captain refused to allow a search, the Leopard opened fire. Twenty-one American sailors were killed or wounded in the attack, which triggered another case of war fever, this time against Great Britain.

As much as Thomas Jefferson hated war, he hated paying tribute more. In 1801, he sent a small fleet of warships to the Mediterranean to protect American shipping interests. The war with Tripoli plodded along until 1804, when American ships began bombarding Tripoli with their cannons.

During this time, one of the ships, the Philadelphia, ran aground on a hidden reef in the harbor, and the captain and crew were captured and held for ransom. Rather than let pirates have the Philadelphia, a young naval officer named Stephen Decatur led a raiding party into the heavily guarded Tripoli harbor and set the ship afire.

After a year of U.S. attacks and a blockade, Tripoli signed a peace treaty with the United States in 1805. Tripoli agreed to stop demanding tribute payments, and in return, the United States paid a $60,000 ransom for the crew of the Philadelphia. This was a bargain compared to the $3 million first demanded.

Pirates from other Barbary States, however, continued to raid ships in the Mediterranean. By the mid-1800s, piracy in the Barbary States finally ended.

Meanwhile, Jefferson tried desperately to convince both France and Great Britain to leave American ships alone. Unfortunately, all of his diplomatic efforts failed, and between 1803 and 1807, Great Britain seized at least a thousand American ships, with France capturing about half that many.

When diplomacy failed, Jefferson proposed an embargo a complete halt in trade with other nations. Under the Embargo Act passed by Congress in 1807, no foreign ships could enter U.S. ports and no American ships could leave, except to trade at other U.S. ports. Jefferson hoped that stopping trade would prove so painful to France and Great Britain that they would agree to leave American ships alone.

The embargo, however, proved far more painful to Americans than to anyone in Europe, and some 55,000 sailors lost their jobs. In New England, newspapers pointed out that embargo spelled backward reads “O grab me,” which made sense to all who were feeling its pinch.

Congress repealed the unpopular Embargo Act in 1809. American ships returned to the seas, and French and British warships continued to attack them.

President Jefferson’s embargo plan proved to be unpopular in America. In this cartoon, Jefferson defends his Embargo Act to a group of dissatisfied men. With the passage of the act, Americans suffered economic setbacks.

embargo a government order that forbids trade with another country

blockade a closing off of an area to keep people or supplies from going in or out

President James Madison took office in 1809. He tried a new approach to protecting Americans at sea by offering France and Great Britain a deal: If you agree to cease your attacks on American ships, the United States will stop trading with your enemy.

Napoleon promptly agreed to Madison’s offer. At the same time, Napoleon’s navy continued seizing American ships headed for British ports. Madison, who desperately wanted to believe Napoleon’s false promise, cut off all trade with Great Britain.

Meanwhile, the British continued seizing ships and impressing American sailors. Madison saw only one way to force Great Britain to respect American rights. He began to think about abandoning George Washington’s policy of isolationism and going to war with Great Britain.

New Englanders and Federalists generally opposed going to war. Merchants in New England knew that war would mean a blockade of their ports by the British navy and preferred to take their chances with the troubles at sea.

Many people in the South and to the west, however, supported going to war. Like all Americans, they resented Great Britain’s policy of impress ing U.S. sailors, and they also accused the British of stirring up trouble among American Indians in the states and territories to the northwest.

Indiana governor William Henry Harrison, on the far left, is shown encouraging his troops during the Battle of Tippecanoe Creek. After the battle, Harrison’s men discovered that the Indians were armed with British guns, which added to Americans’ anger at the British.

Trouble with the Indians was growing as settlers moved into the Ohio and Mississippi valleys and pushed Indians off their lands. Two Shawnee Indians—a chief named Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet—tried to fight back by uniting Indians along the Mississippi River into one great Indian nation. On November 7, 1811, a militia force led by Indiana governor William Henry Harrison fought against Shawnee warriors at Tippecanoe Creek. Although Harrison defeated the Indian forces, after the battle, Harrison’s men discovered that the Indians were armed with British guns.

Americans were outraged. Several young congress men from the South and West, including Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, were so eager for war with Great Britain that they were nicknamed “War Hawks.” They argued that to make the northwestern frontier safe for settlers, the United States needed to drive the British out of Canada. Once that was done, Canada could be added to the United States.

Losses at sea, national pride, and a desire to make the frontier safe for settlement all contributed to the enthusi asm for war, but Madison still hesitated. Was the nation strong enough to launch the arrows of war, or should Madison hold tightly to the olive branch of peace?

James Madison chose to abandon isolationism. At his request, Congress declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. This was a bold step for a nation with an army of 7,000 poorly trained men and a navy of only 16 ships.

Battles on Land and Sea War Hawks were over joyed when the War of 1812 began. They thought that conquering Canada was “a mere matter of marching.” They were wrong. In 1812, 1813, and again in 1814 U.S. forces crossed into Canada, but each time British forces drove them back.

The British, too, found the going much rougher than expected. On September 10, 1813, a U.S. naval force under the command of Oliver Hazard Perry captured a British fleet of six ships on Lake Erie. Perry’s victory enabled William Henry Harrison to push into Upper Canada, where he defeated the British in a major battle. Chief Tecumseh, who was fighting on the side of the British, was killed. However, in December, the British drove the Americans back across the border.

By 1814, Napoleon had been defeated in Europe, and Great Britain was able to send thousands of troops across the Atlantic. American plans to conquer Canada came to an end.

Meanwhile, in August 1814, another British army invaded Washington, D.C. The British burned several public buildings, includ ing the Capitol and the White House. President Madison had to flee for his life.

Next the British attacked the port city of Baltimore, Maryland. On September 13, an American lawyer named Francis Scott Key watched as the British bombarded Fort McHenry, which guarded the city’s harbor. The bombardment went on all night. When dawn broke, Key was thrilled to see that the American flag still waved over the fort, proving that the fort had not been captured. He expressed his feelings in a poem that was later put to music as “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The Shawnee leader Tecumseh tried to unite American Indians in an attempt to halt the advance of white settlers onto Indian lands.

This map shows American and British offensives, or attacks, during the War of 1812. Despite victories on both sides, neither country really won the war. Still, the war had important effects in the United States.

The Battle of New Orleans

A British fleet had surrendered to U.S. forces after the Battle of Lake Champlain in New York just two days before the unsuccessful attack on Baltimore. In Great Britain, news of this defeat would greatly weaken the desire to continue the war. But the news took time to travel, and in the meantime British commanders in the United States launched another invasion. This time, their target was New Orleans.

New Orleans was defended by General Andrew Jackson and a diverse army of 7,000 militia that included a few African Americans, Indians, and pirates. On January 8, 1815, more than 7,500 British troops marched confidently into battle, where they were met with deadly fire from Jackson’s troops. Some 2,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded, compared with only about 70 Americans.

The Battle of New Orleans was the greatest U.S. victory of the War of 1812. It was also unnecessary. Two weeks earlier, American and British diplomats meeting in Ghent (GHENT), Belgium, had signed a peace treaty ending the war. The news did not reach New Orleans until after the battle.

Results of the War Although both sides claimed victory, neither Great Britain nor the United States really won the War of 1812. The Treaty of Ghent settled none of the issues that had led to the fighting. Instead, the problems of impressment and ship seizures faded away as peace settled over Europe. Still, the war had important effects.

First, the war severely weakened Indian resistance in the Northwest Territory. Over the next 20 years, the U.S. government would force most of the American Indians who fought with Tecumseh out of the Ohio Valley and west of the Mississippi River.

Second, national pride in the United States surged. Many Americans considered the War of 1812 “the second war of inde pendence.” They felt that by standing up to the British, the United States had truly become a sovereign nation.

Third, the war had political effects. The Federalists were badly damaged by their opposition to the war, and their party never recovered. Two of the war’s heroes— William Henry Harrison and Andrew Jackson—would later be elected president.

James Monroe became president in 1817. After the excitement of the War of 1812, he was relieved to return the nation to its policy of isolationism. Americans began to turn their attention away from Europe, however, and direct it to events happening in Latin America. From Mexico to the tip of South America, Latin Americans were rising up in revolt against Spain.

Latin America’s Revolutions In Mexico, the revolt against Spanish rule was inspired by a Catholic priest named Miguel Hidalgo (me-GHELL heh-DAHL-goh). On September 16, 1810, Hidalgo spoke to a crowd of poor Indians in the town of Dolores. “My children,” Hidalgo said, “will you make an effort to recover from the hated Spaniards the lands stolen from your fore-fathers three hundred years ago? Death to bad government!” Hidalgo’s speech, remembered today as the “Cry of Dolores,” inspired a revolution that lasted ten years. In 1821, Mexico finally won its independence from Spain.

Two other leaders liberated South America. In 1810, a Venezuelan named Simón Bolívar (see-MOHN buh-LEE-var) launched a revolution in the north with this cry: “Spaniards, you will receive death at our hands! Americans, you will receive life!” José de San Martín (ho-ZAY de SAN mar-TEEN), a revolutionary from Argentina, led the struggle for independence in the south. By the end of 1826, the last Spanish troops had been driven out of South America.

New Latin American Nations Many Americans were excited by independence movements in Latin America. The British also sup ported the revolutions—for their own reasons. Spain had not allowed other nations to trade with its colonies. Once freed from Spanish rule, the new Latin American nations were able to open their doors to foreign trade, including trade with Great Britain.

Other European leaders were not so pleased. They feared that revolu tions, even on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, threatened their rule, and some even began to talk of helping Spain recover its lost colonies. In 1823, Great Britain asked the United States to join it in sending a message to these leaders, telling them to leave Latin America alone.

President James Monroe asked former presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison for advice. Should the United States do something to support the new Latin American nations? If so, what?

A Catholic priest, Miguel Hidalgo (lower center), inspired an independence movement in Mexico. In his upraised hand, Hidalgo holds the flames of revolution that spread throughout Latin America in the early 1800s.

With the Monroe Doctrine by his side, Uncle Sam warns foreign powers to keep their “hands off” the Americas. Even though the Monroe Doctrine is more than 180 years old, it still guides U.S. presidents as they make foreign policy decisions.

Both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison liked the idea of joining with Great Britain to send a warning to the nations of Europe. Jefferson wrote to James Monroe, “Our first and fundamental maxim [principle] should be, never entangle ourselves in the broils [fights] of Europe. Our second, never to suffer Europe to intermeddle [interfere] with . . . America, North and South.”

President Monroe’s secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, agreed with Jefferson. But Adams insisted that “it would be more candid [honest], as well as more dignified,” for the United States to speak boldly for itself. President Monroe agreed.

Monroe Doctrine President James Monroe’s declaration in 1823 that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open to European colonization

In 1823, Monroe announced in his annual message to Congress a policy that became known as the Monroe Doctrine. Monroe stated that the nations of North and South America were “free and independent” and were “not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.” The United States, he said, would view efforts by Europeans to take over “any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.”

Europeans denounced Monroe’s message as arrogant. By what right, asked a French newspaper, did the United States presume to tell the other nations of the world what they could do in North and South America?

Americans, however, cheered Monroe’s message. It made them proud to see the United States stand up for the freedom-loving people of Latin America.

In the years ahead, the Monroe Doctrine joined isolationism as a basic principle of U.S. foreign policy. The doctrine asserted that the United States would not accept European interference in the affairs of the Americas. It also contained another, hidden message. By its very boldness, the Monroe Doctrine told the world that the United States was no longer a weak collection of quarreling states. It was becoming a strong and confident nation—a nation to be respected by the world.

In this lesson, you learned about the development of foreign policy in the United States under the nation’s first five presidents.

President Washington Creates a Foreign Policy The first U.S. president knew that the young nation was unprepared for war. George Washington established a policy of isolation ism to avoid alliances with other countries which could draw the country into wars abroad.

President Adams’s Dilemma During the presidency of John Adams, France attacked U.S. ships. Adams followed Washington’s policy of isolationism and kept the United States at peace by securing a treaty with France.

President Jefferson’s Dilemma President Thomas Jefferson also faced threats at sea. When peace talks failed, he passed the Embargo Act of 1807, which would also prove to be unsuccessful.

President Madison’s Dilemma President James Madison tried to negotiate with both France and Great Britain, but the attacks at sea continued. He finally abandoned isolation ism and declared war on Great Britain. The War of 1812 ended in a peace treaty with Great Britain.

President Monroe’s Dilemma President James Monroe, in support of the new Latin American states, issued a policy called the Monroe Doctrine, which warned European nations to respect the independence of Spain’s former colonies. The Monroe Doctrine established the United States as a strong nation, willing to stand up for its own freedom and that of its neighbors.

In this drawing, the American eagle holds the olive branch of peace in one talon and the arrows of war in the other. Both are necessary to protect the liberty that Americans hold so dear.

Tecumseh, who by all accounts was an imposing figure, was one of the greatest American Indian leaders. This portrait was based on a sketch made by historian Benson John Lossing, who was born the same year Tecumseh died.