BY EMILY BAER

In the quiet hours of a late summer morning, dew glistens on sun-dappled trees in hobby orchardist Karen Hartt’s small grove. Hartt and her husband Ken are careful stewards of 13 heritage apple trees in Franklin and love the rhythm and responsibility that come with growing apples in Maine.

“I believe that protecting and preserving our heritage is important, and apples are part of that,” Hartt said. “Walk along an old rail line where a depot was located and you’ll find apple trees or old farms where orchards were vital to the homestead.”

apples haven’t always been here. Unlike Maine’s other favorite fruit, the blueberry, apples aren’t native to Maine at all.

Apples originated in central Asia and have been revered as powerful, mystical fruits throughout history. In ancient Greece they represented love and promised beauty, vigor, and strength. In Norse mythology, apples were symbolic of youth, virulence, and eternal life. And in Christian traditions they were linked to sin and redemption while also representing knowledge and immortality. When colonizers set sail across the

While it seems almost impossible to imagine a fall here without orchards, ciders, and warm apple pie, apples haven’t always been here. In fact, apples aren’t native to Maine at all.

For Hartt, apples help chronicle a history that is both personal and communal. “I grew up picking wild apples,” she said. “As I got older and started hunting with my dad and husband, I enjoyed trying to identify apples in old abandoned orchards.”

With well over 100 known apple varieties in Maine, enthusiasts like Hartt are blessed with an embarrassment of riches when it comes to choosing their favorites.

“Maine has many ‘lost’ or lesser known varieties, and I love helping heritage apples become more mainstream,” she said.

While it seems almost impossible to imagine a fall here without orchards, ciders, and warm apple pie,

west, so too did their apple orchards. Apples continued to gain traction naturally as a hearty, healthy food staple, but early apple enthusiasts were also skilled evangelists. John Chapman, better known as Johnny Appleseed, spent decades traveling through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and surrounding areas, planting nurseries and spreading the gospel of the Church of New Jerusalem. It was around that time when apples also began to make their way to Maine. In the generations since, farmers have grown apple trees on their land. And if you look closely, you’ll find motley groves of forgotten trees dotting the landscape as far east, north, south, and west as you can get without leaving the state.

and effective way to prevent disease and preserve large annual harvests for enjoyment throughout the year. Cider was often considered safer to drink than water and is credited with helping prevent the spread of disease in newly formed communities across New England. The preservation process could also be tweaked to create apple cider vinegar, which was then used to preserve other fruits and vegetables, dramatically expanding the value and extending the shelf life of common crops in colonial homes.

Atlantic, they packed their ships with apple rootstock and fragile, hopeful trees.

The apple tree’s journey to North America in the early 1500s was as long as it was improbable, but by 1625 they had taken root. It is thought that the first apple orchard in North America was planted on Boston’s Beacon Hill by a man named William Blaxton. The popularity of his Yellow Sweeting apples grew as the city did around him. Soon enough, Blaxton relocated his orchard to Rhode Island, where he found spacious fields in which he could plant expansive orchards and experiment with different varieties.

As the American experiment began to reach across the continent and hopeful travelers moved

Early settlers along the coast, such as in Castine or Brunswick, planted trees on newly claimed land as they sought to tame the landscape around them. Farther south, Thomas Rogers planted a seaside orchard in 1657 in what is known today as Old Orchard Beach. The area's climate was ideally suited for growing apples, but Rogers and his family abandoned the land in 1675 because of ongoing conflicts with local indigenous communities.

At that point, orchards were largely dedicated to producing cider. Cidermaking was brought to America by early English colonizers and proved to be a safe

During the late 1700s farmers began exporting apples by the thousands to enthusiastic consumers across the pond. Benjamin Franklin, who was then traveling overseas, extolled the virtues of Maine’s famous fruit, whetting the European appetite for North American apples and expanding the international market as he went. Within a few short decades, Maine claimed its place as a leading exporter, but their value wasn’t only recognized abroad. The popularity of apple recipes like the Apple Pan Dowdy or Apple Tansey grew as quickly stateside as they did abroad. During the Civil War, Maine apples were even supplied to convalescing soldiers in Washington, D.C.

Daicey Pond Campground cabins in Baxter State Park get much-needed maintenance

BY ANNE GABBIANELLI

Baxter State Park, Maine’s crowning gem, is named after one-time Governor Percival Baxter (1921-1925). As an advocate for preserving Maine’s wilderness, Baxter once said, “I want pleasant foot trails built and attractive campsites laid out in the valleys, by the brooks, and on the shores of the waters. Sites where simple forest lean-tos and small log cabins are available for those who love nature and are willing to walk and make an effort to get close to nature.”

It is one of these sites, Daicey Pond Campground, featuring small log cabins dating back to the 1920s that is getting a lot of attention these days.

“They are primitive cabins,” said Keith Wehmeyer, maintenance and transportation supervisor with Baxter State Park and the lead supervisor of the Daicey Pond Repair Project. “Seven of the cabins are receiving extensive repairs that go beyond routine maintenance, and two of the cabins are being rebuilt within the same footprint and hopefully with the same unique character. It’s not like we are hanging drywall and tackling finish work. The repairs and rebuilds are using 270 spruce logs harvested from the Park’s Scientific Management Area, and as much as we can, we’re getting materials from local resources.”

Daicey Pond is accessible from the Togue Pond Gatehouse; just over 10 miles down the Park Tote Road you’ll find the road to the campground. But the campground actually predates both Baxter State Park and the Tote Road. First established by Maurice York in 1899 as Twin Pine Camps, York built 12 cabins between 1899 and the 1920s, according to Baxter State Park’s official website. The lease remained in the hands of the York family across 70 years and three generations.

As noted on the website, the cabins have been “deteriorating as a result of time and constant use… The work the Park is now undertaking on the remaining cabins represents the next chapter in the long history of this campground. In accordance with Governor Baxter’s wishes, our aim is to maintain the rustic conditions that visitors have experienced at Daicey Pond Campground for the better part of a century. We hope that our careful attention to the aesthetic of these old buildings will result in the maintenance of their original character, and visitors will continue to be able to imagine the rich history of the site.”

“The project was planned by staff with input from a subcommittee of the Baxter State Park Advisory Committee with final approval given by the Baxter State Park

In 1873, the newly incorporated Maine Pomological Society (MPS) held its first meeting. In the 150 years since, the society has dedicated itself to strengthening Maine’s agricultural industry and the apple producing sector in particular by connecting apple orchards and growers throughout the state.

These days, MPS gathers information from growers, universities, and other sources and represents grower's interests at various agencies and legislative bodies.

close working partner of the Maine Pomological Society, focuses on sharing research-based information with the public. Through workshops, meetings, farm visits, and virtual consultations, they’re able to help professional farmers and amateur growers build on 400 years of knowledge and continue to foster the tradition of apple farming in Maine.

The Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association is similarly dedicated to education and preservation.

throughout the state. By looking back at the genetic makeup of each apple, researchers are able to piece together the puzzle of Maine’s apple history. Bit by bit, they are fleshing out a story only the trees themselves could tell.

(Below) Daicey Pond Cabin 1, known as “Owl’s Nest,” undergoes extensive repairs.

Authority,” Wehmeyer said. “The input from the subcommittee, which was composed of folks with a variety of skills and attachment to Daicey, was valuable.”

It’s been a team effort, from the project planning, which began in 2021, to the target completion date of May 2025.

“We are boots on the ground with a designated crew of four, and some campground rangers with a wide variety of skills pitching in when they can,”

Wehmeyer said. “We also have plans to bring in volunteers.”

The campground is open for day use only this season while the repair project is taking place.

“Some people hold Daicey near and dear, with generations of families returning every year,” Wehmeyer said. “Our effort is to keep the spirit and unique character of the cabins the same while preserving them for years to come.”

And what’s next once the Daicey Pond Campground cabins are completed?

“There will always be more projects as the Park is of an age that its infrastructure needs attention,” Wehmeyer said.

You too can follow the progress being made at Daicey Pond Campground here: baxterstatepark.org.

MPS also funds research and maintains a database of Maine growers.

“MPS has evolved alongside the growers,” said MPS board member Shane Patrick. “Discussions still involve how to deal with insects and diseases and marketing and labor issues. It’s much the same as 150 years ago, but we no longer talk about the quality or quantity of the apples shipped to England.”

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Tree Fruits Program, a

MOFGAs Maine Heritage Orchard is 10 acres of living agricultural history. The orchard is home to more than 360 traditional Maine apple varieties, and they are working with farmers and foragers to find and catalog trees that have gone unrecognized or have nearly been lost to history. Thanks to a partnership with the College of the Atlantic and Washington State University, they are slowly but surely cataloging and analyzing the DNA of well-known and newly discovered trees

Conant Orchards in Etna is writing the apple industry’s next chapter as they go. Since 1945, they have been growing and selling apples to families who are drawn to their delicious products and friendly, rustic atmosphere. Over the years, the orchard’s offerings have expanded to meet the enthusiasm and loyalty of their customers. Their success is due in part to their ability to bring visitors into the fold.

“Most of our customers have come their whole life and make it a tradition every year,” said manager Hannah Hegarty. “Our favorite part of this business is the heritage and the community. We love the history.”

For four generations, that has meant “you-pick” apples, cider, donuts, and fall

farm fun. These days their stand also carries local jelly and cheeses, pickled vegetables, apparel, and beloved applecider slushies. It’s a celebration of Maine farmers and foods, and families return year after year to enjoy the richness of that legacy.

As summer turns to fall and the temperatures begin to cool, Maine’s apple harvest will begin once again, just like it has every year for nearly 400 years. Pickers at Conant Orchards and others like it will delight in finding Galas and Honeycrisps. Others, like Hartt and her fellow hobbyists, will bite into the deep purple rind of a Black Oxford or the crisp crimson blush of Jonagold. Regardless, their harvest tells a story of both our past and present.

“Apples are grown on every continent save Antarctica,” Patrick said. “They've made their way into the lexicon and mythology of the nation. Maine is smalltown America and here our trees are laden with apples in autumn.”

FHow it pays to spend time in nature

COURTESY OF METRO CREATIVE

ew things can be as distracting as a beautiful day. When the weather outside is welcoming, it can be hard to focus on indoor activities, including work and tasks around the house. Though it's not advisable to ignore responsibilities at work and at home when the weather outside beckons, it can be beneficial to spend ample time in nature when circumstances allow.

People tend to flock to the great outdoors in spring, summer and fall, and some are even so devoted that they bundle up and head outside throughout winter. Whether they know it or not, people who love to spend time in nature are doing their mental and physical health a lot of good by embracing the great outdoors.

The National Alliance of Mental Illness notes that a growing body of research supports the idea that time in nature is good for mental health. A 2015 study from researchers at Stanford University found that people who walked in a natural area for 90 minutes exhibited decreased activity in a region of the brain associated with depression compared to those who walked in high-traffic urban settings.

The United Kingdom-based Mental Health Foundation also touts the mental health benefits of the great outdoors. According to the MHF, research shows that people who are connected with nature are more likely to report their lives are worthwhile than those with no such connectedness. In addition, the MHF notes time in nature has been shown to generate positive emotions, including calmness and joy, and promote greater creativity.

When seeking to capitalize on the mental health benefits of time in nature, people should know that where they spend time

outdoors matters. As the Stanford study indicated, time outside in high-traffic urban settings may not produce as profound an effect as time spent in natural settings, like forests, that tend to be more serene. People who live in cities or other densely populated areas can still benefit from time outdoors, but they might experience even greater health gains if they make consistent efforts to spend time in more natural settings.

PHYSICAL HEALTH BENEFITS

The physical health benefits of time in nature are equally notable. Perhaps the most obvious physical benefit is related to physical activity. People tend to embrace physical activity when spending time in nature. Hiking, jogging, walking, nature-based recreational activities like kayaking, and playing sports like basketball or pickleball all involve physical activity, which can help people avoid the consequences of a sedentary lifestyle, such as an increased risk for chronic diseases.

More specifically, physical health benefits of spending time outside include:

· A STRONGER IMMUNE SYSTEM

· LOWER BLOOD PRESSURE

· INCREASED ENERGY LEVELS

· IMPROVED SLEEP

Each of those benefits contributes to greater overall health, making time outdoors among the more beneficial behaviors a person can embrace.

There’s no shortage of benefits to spending time in nature. That’s something to keep in mind the next time welcoming weather beckons you to get some fresh air.

BY KATIE BINGHAM-SMITH

There’s something about getting out in nature when the leaves change and the air is crisp. And when your dog can join you it makes things even better. Here’s a list of scenic walking trails that welcome pets. Load up the car and head out for the day to explore one of these majestic trails — and bond with your pooch this fall.

Bring your fur baby and some lunch to Bangor Forest City, where you’ll enjoy plenty of walking paths to build up an appetite for lunch or a snack at one of the picnic tables. Many of the trails are open and wide, with plenty of places to stop and take in the sights. Just note that dogs are not allowed on the Orono Bog Boardwalk.

Located in Swanville, this state park includes 67 acres, and offers a 1.5-mile long walking trail for you and your leashed pet. There’s also a wonderful playground for the kiddos, plenty of picnic tables to enjoy a meal, and a place to put in a canoe. There’s something for everyone, so bring the entire family (including your dog) and spend the day looking at the beautiful foliage and taking in the fall air. Be aware dogs are not allowed on the beach between April 1 and Sept. 30.

Located on the outskirts of Bangor, Brown Woods is a secluded little spot that will make you feel like you are far away from the city. Leased pets are permitted on the easy one-mile loop. Brown Woods is a free place to walk your dog, see the changing leaves, and a great escape from the hustle and bustle of life.

From the entrance at the end of Watchmaker Street in Bangor, Essex Woods offers a variety of trails for all types of hikers and all types of dogs (plus a great hill for sledding in the winter). In addition to the miles of trails, there are multiple dog parks — one for big dogs, one for small dogs, and a fenced agility course that doubles as an area for dogs who prefer to play by themselves. The parks are a great place for your furry friend to be off leash and running free. It’s a beautiful place to take in the natural landscape in the fall, and tucker your pet out.

If you’re looking for a paved walk, you’ll love the Bangor Waterfront Trail located along the Penobscot River in Bangor. It’s a scenic trail with water views where leashed pets are welcome. The walk is a mile one way, and you can’t beat the water views. You may even find some food trucks along the way.

BY JUDY HARRISON

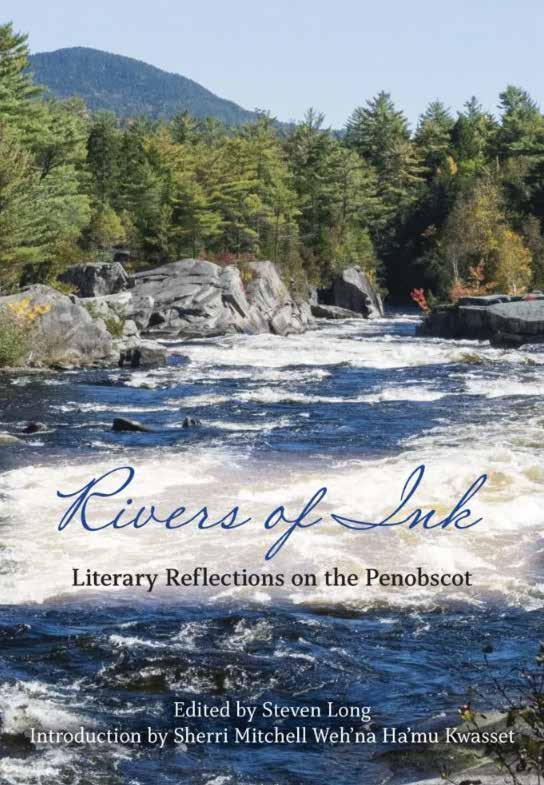

The mighty Penobscot River and its tributaries have inspired writers and storytellers for centuries. Recent reflections on its history and impact on people who spent time on its banks and its waters are included in “Rivers of Ink: Literary Reflections on the Penobscot.”

Sixty-one Maine writers contributed to the book. It includes poetry, essays, short stories, and memoirs. It was published by 12 Willows Press of Winterport. Sales go to support the Friends of Katahdin Woods & Waters’ campaign “A Monumental Welcome.” Those plans include a new visitor contact station, priority park projects, and Wabanaki-directed initiatives.

Publisher and editor Steven Long said that he received about 70 submissions, expecting that about half of them would meet the criteria. He invited people from all walks of life and age to submit work and was pleasantly surprised to be able to publish nearly all of them.

“I'm pleased that the end result reflects this inclusivity,” he said. “This anthology features the poems of two high schoolers alongside works by other writers, some professional and some just starting out. The quality of writing and the skill of the writers are simply amazing, making it impossible to distinguish between the seasoned authors and the newcomers.”

“I remember watching him paddle and noticing tenderness in his movement,” Mitchell wrote. “A type of tenderness that was not rooted in gentleness or affection but instead an expression of reverence.”

One of the most moving pieces in the book is “Letting Go: Down by the River” by Annaliese Jakimides. She wrote of scattering her son’s ashes on the river on a November morning.

“I balance us down the hardening bank, a new slipperiness underfoot, until I reach the place where I know I will be able to kneel, linger a bit, and let my child go.”

The introduction to the book, published last year in connection with the Bangor Authors Book Fair and Literary Festival, was written by Sherri Mitchell Weh’na Ha’mu Kwasset, a member of the Penobscot Nation and author of “Sacred Instructions: Indigenous Wisdom for Living Spirit-Based Change.” She explained how the river is the first citizen recorded on the tribal census and included a history of the river since the 1600s, when European settlers “brought industrial activity” to Wabanaki territory. But the author added some personal memories about how her grandfather taught her how to paddle a canoe without disturbing the water.

In her poem “The Penobscot Outside My Window,” Rhea Cote Robbins wrote of how she followed the seasons for the 41 years she lived along the Penobscot. Poet Patricia Smith Ranzoni was inspired to write “Restoration” in commemoration of the June 11, 2012 removal of a dam on the river to allow Atlantic salmon to return to their traditional spawning grounds. A similar book will be published this year for the 3rd annual Bangor

Authors’ Book Fair and Literary Festival to be held Saturday, Dec. 14 from 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. at the Bangor Public Library. The title of the new publication is “North Woods at Night: Literary Reflections on Maine’s Largest Forest.” Submissions, with a limit of 2,500 words, closed April 30. It too will be published by 12 Willows Press. Proceeds from sales will be donated to the Forest Society of Maine, a non-profit that has helped conserve more than one million acres of forestland since its founding in 1984.

This year’s keynote festival speaker will be Paul Doiron, author of the Warden Mike Bowditch mystery series. Nearly 100 authors took part in last year’s festival and about 1,600 people attended. Maine authors who have published one or more full-length books are invited to sell their books. There is no entrance fee but authors are asked to donate a book for the raffle.