6 minute read

ARCHITECTURE

from MONEY ISSUE 64

THE MASTER ARCHITECT

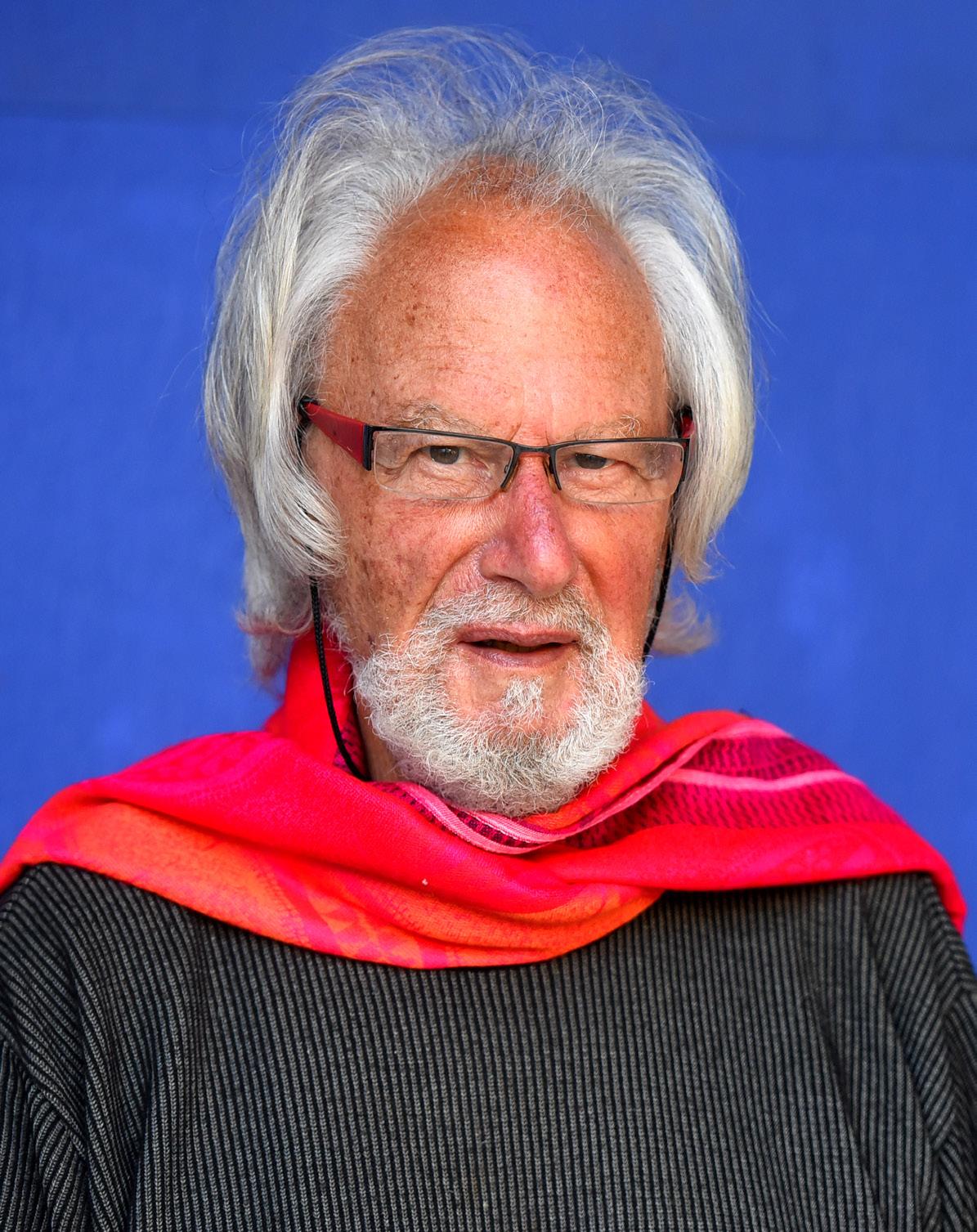

British author Chris Abel describes Richard England’s contribution to the post-war culture of Malta as unique. Visionary architect, artist, critic, poet and landscape designer, England is the personification of the fusion of the arts promised by the modern movement, but rarely delivered. Amongst his best-known designs, his masterpiece, Manikata Church, stands amongst the most original regional modernism works of its time. Lea Hogg talks to Malta’s internationally acclaimed architect Richard England about the past present and how his work brings him closer to God.

Advertisement

In his book ‘The Architecture of Happiness’, Alain de Botton says, ‘A good building can enhance your life, and a bad building can ruin it’. And England firmly agrees with this.

In the quiet residential part of St Julian’s, an area where families settle and stay put for an entire lifetime, close to the busy nightclub area and yet so peaceful, one finds Professor Richard England’s spacious home, which he designed and built, and where he has lived with his wife Myriam for the last 57 years.

Richard and Myriam sit side by side at ease on the large sofa in their airy living room, discussing Myriam’s forthcoming virtual international ikebana conference. They are a team. Myriam describes their home as a real work of art, very peaceful and excellent for meditation. ‘This is where we unwind, entertain, where we have watched the children and grandchildren grow up, and where we find sanctuary and connect with the people closest to us,’ she says.

‘I have been influenced by relationships with two extraordinary people in my life,’ England says. ‘One was Father Peter Serracino Inglott, who was my mentor for many years. Of course, the other person is my dear wife, Myriam. Her spirituality has engaged me in further research, and her encouragement and support have allowed me to focus on my works.’

Award-winning, internationally acclaimed architect Richard England has many talents. His natural ability fused with years of pouring hard work and passion into every project he has designed brought him outstanding success in several different artistic fields. Quentin Hughes OBE, known for his preservation work of Liverpool’s Victorian and Edwardian architectural heritage, described Richard England as ‘an architectural sculptor with a respect for the past and an admiration for the present.’

When he was 23, England returned to Malta after studying in Milan and an internship with Gio Ponti. At that time, his father, Edwin England Sant Fournier, also an architect, was commissioned to design and build the Church of St Joseph in the northern village of Manikata. England’s father gave him ownership of the project as a reward for his successful studies abroad.

Despite the Manikata church being England’s first work, it remains one of his best-known ones. England says, ‘The Manikata church was a fascinating process because it was built by voluntary labour. This meant that I had to conduct the whole issue, almost in a mediaeval way. I always say to my students, occasionally, make a building with your hands.’

England firmly believes that apart from an architectural assignment’s apparent objective to create a building to its maximum use, a good architect must feel an element of love and dedication and commitment towards a building project. He adds, ‘The building absorbs an architect’s love for the materials he uses, and this positivity is then passed back to the people who will use the building.’ →

England confesses that he feels uncomfortable when owners change the design of a finished building. He says, ‘I prefer it if buildings are destroyed rather than changed. When they are changed, they almost look deformed to me. As an architect, you cannot help but feel a bit possessive towards each building project and even experience a sense of loss when one sees that changes have been made to the building, which may sometimes result in a clash of styles. You somehow feel that a building is yours. Once it is completed and passed back to the owner, it is a little bit sad to see unexpected changes, but it is an acceptable part of the process of architectural design.’

There are a lot of construction projects taking place on the island, bringing about many changes. ‘We may think of architecture as something which does not change,’ says Richard England, ‘but what is extremely interesting is that permanent architecture does not exist.’ He explains that architecture is transient and remains the only form of art that people feel they can change. ‘Nobody would touch a painting after it is finished, nor add a pair of wings to a sculpture.’

When a building project is complete, the onus is no longer on the architect but entirely on the owner. ‘The time comes when the architect hands over a building to the client. The property now belongs to the client, and he can do whatever he likes with it. The owner may even choose to demolish the building if in time the land happens to cost a little bit more than the purchase price.’ England refers to the new developments we see on the island. ‘Of course, the change in Maltese architecture is a constant necessity, and there are many changes on the island. Some of the changes are necessary. The change in Valletta is necessary. For example, the Renzo Piano project is necessary. It's a tremendous work of art, and it has brought Valletta into the 21st century.’

In his book ‘Eupalinos and the Architect’, Paul Valéry describes three types of buildings; the ones that are mute, buildings that speak and there are buildings that sing. England says that the buildings which sing are the ones which touch your heart and refers to the great modernist master, Le Corbusier, who said, ‘You use tone, you use concrete, you build a house—that is construction. You touch my heart—that is architecture.’

Craig Macdonald, co-founder of Te fitTazza, has produced a showcase of Richard England's architectural vision in a recent collaboration with him. Craig explains, ‘Sadly these days we see less of Richard England’s approach to architecture which is aesthetically beautiful and yet retains its regional influence. This will harm our architecture and will undoubtedly fail to preserve Malta's unique identity.’

Richard England describes architecture as functional art. A building needs to be well made and designed by how different materials are put together in a valid construction methodology. Commodity and firmness belong to construction. What lifts that building is beautiful, and it isn’t easy to define beauty. He says, ‘What I have always tried to do is to create architecture which enhances the spirit and lifts the soul so that when you see a building and go into it, you feel what that architecture is all about. The aesthetics of architecture are important. But what architecture should do for us is far more important.’

Winston Churchill said, ‘We shape our buildings, and after that, the buildings shape us.’ England concludes, ‘There are many roads to God, and I have chosen architecture.’

Words by: Lea Hogg is a TV producer and hosts a daily evening current affairs and lifestyle show. She produces multi-media content for several international corporates.