8 minute read

The Shepherds of the Bees

David Wainwright, Tropical Forest Products Ltd, Aberystwyth, UK

David Wainwright is a commercial beekeeper with over 1,500 colonies across 100 apiaries in the UK. In addition to beekeeping, David runs a highly successful business, marketing his own honey and hundreds of tonnes of honey and beeswax imported every year from Africa. David supplies this honey to Marks & Spencers and other major retailers in UK. David knows much about beekeeping in Africa, having lived and worked in Zambia since the 1980s, and has collaborated with Bees for Development on several projects over the years. David agrees with Bees for Development’s view that frame hives never function well in tropical Africa. This is the first of three articles in which David discusses his approach to making good business from beekeeping.

In these three articles I will show that it is possible to produce good honey crops without invasive colony management if a good strong generation of young stock is produced every year. I will use production data from my own hives to demonstrate the results achieved. Although I am using frame hives these methods can be applied as well to fixed comb, local style hives with the same large honey crops harvested.

Well-made hives

I first started my bee farm in the UK in 1977 with a few old bee hives from under a thorn hedge that I managed to buy cheaply. It has grown to 1,500 honey bee colonies, still expanding every year, with all those old hives even now in use today - they were very well made!

Over the years my methods have grown simpler as I have found that bees thrive best when left to manage themselves without beekeepers thinking they know best and interfering too much. With our simple methods we produce large crops of honey, compared to many other bee farmers using more intensive management techniques. We produce an average of 42kg honey from our colonies compared with the 20kg average1 for UK professional beekeepers. The average crop of the bee farmers participating in our Knowledge Exchange Group2 is 35kg.

We think of our so-called ‘modern’ frame hive beekeeping as a rational and more productive improvement from the old fashioned, simple and apparently inefficient methods of previous generations. We assume that our ‘modern’ hives produce far larger crops than these previous generations with their simple fixed comb hives. But over the years I have come to doubt this assumption which seems to be based on little recorded evidence of the productivity of the earlier methods. Unfortunately, in Europe very little was recorded before the ancient straw skep hives were swept away to be replaced by frame hives.

Good yields

The skep beekeepers were practical farmers, they were too busy to write books, with one exception: A. Pettigrew who recorded honey production from skeps in his Scottish village of Carluke around 1875, where colonies were producing on average about 43kg of liquid honey per year, with exceptional hives reaching 75kg. These crops would have been amongst the best achieved in those days I suspect, and there are few UK frame hive beekeepers today who exceed these figures. African beekeepers using large log hives in favoured locations, for example south-west Ethiopia, also produce around 40kg. It seems to me that the crop of honey is not related to the type of hive: similar good crops can be achieved from all types of hives, what is important is to nurture strong healthy colonies of bees.

Production per frame hive managed by professional beekeepers currently in the UK is about 20kg per year: probably not a lot higher than from the old straw skeps. In addition, the health of the modern bee population is poor, the genetic diversity is low and the total number of colonies in the country has declined.

An expert Ethiopian beekeeper. This large hive will support a colony with high bee numbers capable of building a large crop. The beekeeper can carefully crop part of the honeycombs several times a year: they work gently to minimise stress to the colony. They expect around 40kg per hive, similar to my frame hives in the UK

Photos © David Wainwright

I have concluded that the ancient, fixed comb hives of Europe and Africa have some advantages over movable comb hives which can enable a healthy and vigorous stock of bee colonies to be established over successive years. This is not to do with the management of the bee colonies by the beekeeper: it is due to how the beekeeper provides the bees with the resources they need to grow unhindered and maintain their vitality. I have tried to incorporate these features into the management of my own bee farm. The results measured in kilograms of honey produced per hive have been encouraging: better than many highly managed colonies and less labour intensive.

Well cared for will thrive

In fixed comb hives the colony is not manipulated for routine examinations, swarm control, requeening etc, this avoids stress which can have long term detrimental effects on the colony. Instead, the beekeeper concentrates on providing the developing colonies with a secure home and plenty of food, like a shepherd caring for the new season’s lambs.

There are many parallels between this approach to beekeeping and successful practices in livestock farming, which includes modern methods based on scientific studies as well as methods of bygone generations based on astute observation and experience. I try to reduce stress to my colonies by opening the hive only when it is necessary, which is typically about three times per year. Avoiding stress is also important for cattle. For example, cattle stressed by poor handling will lose growth rate, while happy cows will produce more. So many farms now are incorporating features designed purely to reduce stress and give the cattle a feeling of wellbeing. I try to make sure that my young colonies (nucs) have everything that they need during their period of rapid growth in the first weeks of their life. The first weeks of a calf’s life are critical, it must have colostrum within six hours and if it grows fast it will grow to become a productive cow with a high milk yield. It will produce more milk over its lifetime than a cow that started life as a calf struggling to find food.

If year after year the stock of bees is well cared for, in a way that minimises stress, then each successive generation starts from a slightly better position than the last and the improvements build upon each other, generation by generation. In this way a strong healthy stock of colonies is built up, well fitted to the management techniques of the beekeeper and the environment around them. I have noticed that each beekeeper has slightly different stocks of bees, even if they are using similar queens.

When I started out on my bee farming career I worked as an apprentice to a famous bee farmer, David Rowse and I read every book on the subject I could find. David Rowse and all the authors of the bee books aimed to keep every one of their colonies in a peak of honey gathering performance by managing the colony, which meant opening each colony every 10 days for an inspection, various manipulations to prevent swarming and replacing the queen every two years. In contrast I only open a colony three times a year and rely on harnessing the natural vigour of the bee colony when it is left alone to develop through its life cycle over 3-4 years.

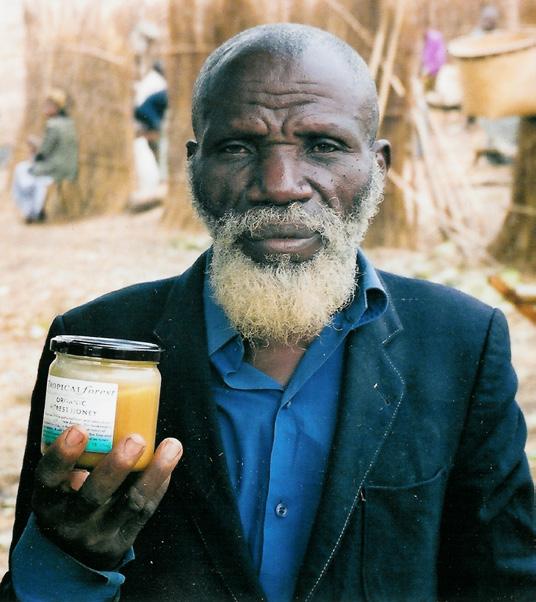

Jaam Mamayami with honey from his bark hives. I have imported this honey from the same Zambian beekeepers and their descendants for over 30 years. It is sold throughout the UK and has won many awards for its outstanding taste, for example Great Taste Awards 3 Stars

Bark hive beekeeper shepherds

I first started to question my beekeeping education when I worked in north-west Zambia in the 1980s. I had been sent there to train beekeepers in frame hive beekeeping, so I established several apiaries of frame hives. After a lot of effort transferring swarms out of bark hives I had about 100 colonies, but these bees failed to thrive and produced very little honey. To make sure forage was adequate I situated my hives in the villages where bark hive beekeepers were producing plenty of honey. The bees in the bark hives were thriving but the bees in the frame hives were struggling to survive. After a couple of years, I gave up on frame hives and concentrated on trying to understand what the bark hive beekeepers were doing right.

What I found was that the bark hive beekeepers worked like “shepherds of bees”, they have a flock of hives which consists of young growing stock in their first year and productive stock in their second and third year which will be cropped at the end of the season. The young ones, which are growing rapidly, will be next year’s honey producers. Second and third year hives are the productive stock which will be cropped this season. These beekeepers did little to manage individual hives, but they managed their whole flock of hives, each hive in an age group would get the same treatment. They tried to utilise the vigour of a swarm that has newly occupied a hive and is building white comb at a phenomenal rate. There were very few colonies which stayed in hives for years, as a bark hive only lasts 4-5 years, so most colonies were starting in a clean fresh hive. This is very similar to how skep beekeeping was practised in the UK before the advent of the frame hive.

References

1. National Honey Monitoring Scheme, UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. https://www.ceh.ac.uk/

2. Knowledge Exchange Group (a UK Bee Farmers Association Initiative with seed funding from the Waterloo Foundation. Six bee farmers who agree to share performance data on a transparent and confidential basis, measuring and comparing farm outputs and costs, thereby learning from each other’s achievements and mistakes)

3. Espregueira Themudo,G.; Rey-Iglesia,A.; Robles Tascón,L. et al. Declining genetic diversity of European honeybees along the twentieth century. Sci Rep 10, 10520 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67370-2