44 minute read

The ends justify the search

Computer modeling has helped Belarusian scientists to find chemical compounds blocking the coronavirus

The question of how to treat pa‑ tients with coronavirus is still open. Not wonder, the minds of many researchers around the world are put to the search of a targeted anticoronavirus agent. Our sci‑ entists are also contributing to this work. Project Manager — Director of the Unit‑ ed Institute of Informatics Problems of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus Alexander Tuzikov, reveals some details.

Advertisement

With a long-term perspective

There’s a near and far future in drug de‑ velopment. Usually they are developed for s pecific diseases, and it is a complicated, long, expensive process. But when there are emergencies like the current pandemic, the natural approach is to choose the options from the existing drugs. In recent months, there has been a lot of news from various re ‑ search groups offering not only well -known antiviral drugs, but also antiparasitic and even hormonal drugs to treat COVID‑19. It does not mean that they are well suited for the new role, because they were originally created for the treatment of other diseases. But when you need to urgently decide on the treatment and it is necessary to have at least some drugs, this is a way out. — The fact is that a drug is not just a chemical compound that has a neu‑ tralizing effect on, say, bacteria and vi‑ ruses. It is important that it has also gone t hrough a long process of verification of

useful properties, meets many require‑ ments, including safety, has minimal side ef fects. That is why, in urgent situations search for already known drugs that have been clinically tested is the fastest way. Re‑ cently, a large number of such studies have b een conducted, many articles have been published. But today, there are no drugs specifically targeted against SARS-CoV‑2. And we are in the process of creating them, which is a long-term issue, — A lexander Tuzikov introduces us to the problem

The research group includes the staff of the Laboratory of Mathematical Cybernet‑

Alexander Tuzikov

ics of the UIIP NAS, which is headed by our interlocutor, as well as representatives of the Institute of Bio-Organic Chemis‑ try of the National Academy of Sciences, Doctor of Chemical Sciences Alexander Andrianov and Candidate of Chemical Sciences Yury Kornoushenko. Such an al‑ liance is not accidental.

A significant role in the creation of new drugs is now played by computer modeling, computer search of compounds that can potentially become effective drugs against this coronavirus, and then they are tested in practice.

Five contenders

The joint team started working back in February. By the time, publications related to the study of different aspects of the new coronavirus had appeared. Its genome was revealed, there was information about some proteins of the virus, vital for its de‑ velopment, reproduction inside the body. — At the end of February in interna‑ tional open data bank three -dimensional structures of some proteins of the new coro‑ navirus were published. And this informa‑ tion was the starting point for our research. W e could take the three-dimensional struc‑ ture and start the work on search of chemi‑ cal compounds, which would block the a reas important for vital activity of this pro‑ tein. By the end of March we received the fir st results, — says Alexander Vasilyevich.

Work of specialists on bioinformatics and computer modeling helped to carry out this important initial stage on selection of the most suitable substances for medi‑ cine creation within a very short period of time: performed manually, this kind of selection would take years.

For the database of chemical com‑ pounds, with which our scientists worked, has more than 200 million variants! — Our team used the possibilities of powerful computers to look through this database and find those compounds, which meet the requirements to medicines: they

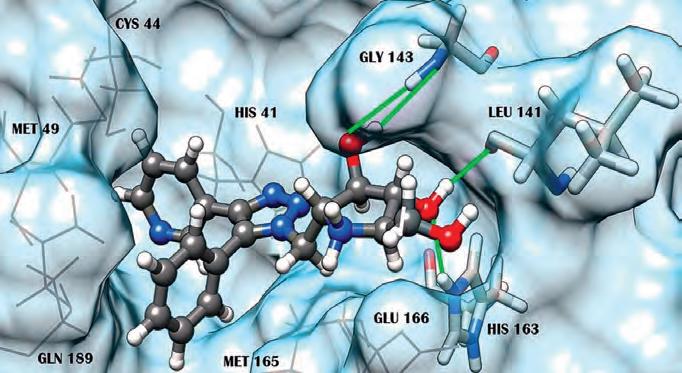

An example of interaction of one of the obtained compounds with the coronavirus target protein

should have small molecular mass, have cer‑ tain solubility and so on. As a result of the s creening, these options were selected. And then such procedures as molecular docking, quantum-chemical calculations and molec‑ ular dynamics, requiring a lot of computer r esources, were applied to them in order to select those molecules, which block specific targets and the reproduction of a given pro‑ tein. As a result 5 compounds with neces‑ sary properties were found — surprises us t he project manager.

Global task

The scientific world has responded quickly to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Already in January, a competition for projects related to coronavirus was an‑ nounced in Europe — in the field of di‑ agnostics, drug development, vaccines… F or the implementation of 18 best of them 48 million euros were allocated. On 20 May, a new competition was an‑ nounced with funding of 122 million eur os. The USA, China, Russia and other countries are also investing huge resourc‑ es in this area. — The mankind understands that this is a strong threat and it is not the last one. We need technologies that will en‑ able us to respond quickly to such chal‑ lenges.

The pandemic has shown that, unfor‑ tunately, mankind is not ready to promptly deal with biological threats. New proven approaches are therefore needed to rapidly create effective drugs.

Computer methods make it possible to optimize part of the process. There is no other alternative for rapid development, — Alexander Tuzikov is sure.

The Belarusian team carried out the work on its own initiative in the frame‑ work of fundamental research programs that are now being implemented in the NAS. N ow we need the next stage — a joint project with chemists, physicians to test the results in practice. Such an appli‑ cation has already been submitted to the working group on combatting coronavirus created in the NAS. By Yuliya Vasilishina

A city which is comf ortable in every sense

Today, statistics eloquently show that private and commercial road transport accounts for the lion’s share of exhaust emissions in the transport sector in most countries. Undoubtedly, a private car provides the best freedom of movement and additional business opportunities. However, its unreasonable use creates many problems, especially for the environment, safety and health of citizens. “Smart”, “green” city... An increasing number of settlements in Belarus are choosing urban development models aimed at making cities more comfortable and convenient for people, rather than for transport or industrial enterprises.

TThe project “Green Cities”, funded by from theory to practice. In fact, it is a new the Global Environment Facility and im‑ practical document of strategic planning plemented by UNDP together with the of urban development. After all, besides Ministry of Natural Resources and Envi‑ the quality of the road network and the ronmental Protection of the Republic of work of urban transport it affects many Belarus, has developed a new document other aspects, i. e . the environment, health, for the country, i.e. the Sustainable Ur‑ accessibility of the urban environment for ban Mobility Plan for Polotsk and Novo‑ people with disabilities. polotsk. No doubt, for a modern city such — The work on such a document al‑ a plan is an important strategic document lows to take a fresh look at the state of of development. the city,— says Igor Pankov.— I believe —Mobility is, first of all, the availabil‑ that the main problems, which all Bela‑ ity of facilities, services and information rusian cities face regardless of their size f or citizens in the city and about the city,” Igor Pankov and status, were specified in the Plan of said Igor Pankov, Executive Director of the Sustainable Urban Mobility for Polotsk

Republican Public Association “Belarusian get to a particular object or event in a con ‑ and Novopolotsk. Yes, the Sustainable Ur‑

Union of Transport Workers”, expert of venient way. ban Mobility Plan for Polotsk and Novo‑ the project “Green Cities” on the develop ‑ It should be noted that for Belarus, polotsk offers a comprehensive approach ment of a sustainable urban mobility plan the development of sustainable mobility that has not been applied in the country f or Polotsk and Novopolotsk. — This is the plans is the first experience of this kind, before. For the first time in Belarus, a qual‑ realization of the right of every person to including for experts who are moving itative picture has been obtained — how

and where people move in regular com‑ munications. Thanks to the large amount of data obtained, a correspondence matrix was built and it turned out that, in gener‑ al, the structure of urban mobility is quite stable. The picture, even by European standards, turned out to be good — only about a third of Polotsk and Novopolotsk citizens move daily in private or depart‑ mental cars. The rest prefer public trans‑ port, bicycles or walk, in other words, use sustainable means of transportation. — I t’s another matter how good and comfortable these types of movement are — that’s what we need to work out in the future, — said Igor Pankov. — In any case, the city authorities have received a qualitative basis for further development and dialogue with citizens, saw what prob‑ lems are the most acute, what to start with.

According to the expert, an impor‑ tant element in the development of a sus‑ tainable urban mobility plan for Polotsk and Novopolotsk is the organization of a dialogue between the city authorities and residents. First of all, it is important to understand what problems exist from the point of view of the citizens. On the one hand, such a dialogue helps to rank the problems, on the other hand, to in‑ volve the citizens themselves in activities to solve them. — A lot of things can be done with your own hands, — Igor Pankov is sure. —

On the street of Polotsk

And the city authorities should provide administrative support, assistance in ob‑ taining some kind of permits. It is impor‑ tant to involve business in such a dialogue, for example, for the improvement of urban areas adjacent to some business centers, office buildings.

The expert believes that there are many options for solving urban devel‑ opment issues. Taking into account the economic situation, the developers have put into the document low-budget, but effective solutions. Development of cy‑ cling and bicycle infrastructure, develop‑ ment of adequate parking policy, rank‑ ing of streets, constructive decisions on arrangement of public transport stops, optimization of throughput capacity of transport hubs — these are the first steps specified in the Plan, which do not require large financial injections. Many of these solutions are already being implemented by the project “Green Cities” in Polotsk and Novopolotsk. — W e have been working closely for the last five years to improve traffic or‑ ganization in Polotsk,— says First Deputy Chairman of the Polotsk District Execu‑ tive Committee Sergey Leychenko.— The experience we have gained shows that with the help of simple budget measures, we can change the state of mobility in the city for the better. It is not necessary to buy expensive equipment, set new traffic lights, qualitative analysis and introduc‑ tion of modern European solutions in the organization of road traffic are enough. Yes, some changes at first do not resonate with motorists. However, we must remem‑ ber that the streets are designed not only for cars, but also for pedestrians, cyclists, people with disabilities. Together with the project “Green Cities”, we are trying to create comfortable conditions for all road users.

One of the most interesting innova‑ tions that GEF -UNDP-Ministry of Natural Resources project “Green Cities” is imple‑ menting in Polotsk, is the introduction of an innovative scheme of traffic organiza‑ tion, which will bring visible changes in functioning of transport in the central part of the city. Some solutions will be applied for the first time in Belarus. For example, a new type of artificial uneven‑ ness, the so-called “bus/speed cushions”, will be introduced. They should not cause discomfort to public transport and its pas‑ sengers, but reduce the speed of passenger cars only.

In addition, for the first time in Bela‑ rus there will be traffic zones for vehicles with a speed limit of 30 km/h on small streets of local importance. This is done for the comfort and safety of pedestrians.

An innovative road traffic manage‑ ment scheme also has a number of envi‑ ronmental benefits. Firstly, the new du‑ rable markings will eliminate the annual renewal of road markings with enamel, which contains a number of harmful sub‑

Sergey L ey chenko

stances. Secondly, traffic is ordered — it moves steadily, with less acceleration — braking, with less fuel consumption. Accordingly, emissions of harmful sub‑ stances into the atmosphere are reduced and the quality of the environment is im‑ proved. Thirdly, there are more walking and cycling opportunities, which have a positive impact on human health.

Experts note the first positive points, which confirm that the city authorities of Polotsk and Novopolotsk are actively working with the Plan of Sustainable Urban Mobility. In particular, Novopolotsk has signed a memorandum of understanding with the European Bank for Reconstruc‑ tion and Development and is negotiating a credit line to extend the tram network in the city. And for the EBRD, having a Sus‑ tainable Urban Mobility Plan for the city is a prerequisite for cooperation. If there is no plan — there is no financing.

Albert Shakeel, Deputy Chairman of the Novopolotsk City Executive Committee:

“The long-standing idea of our city, which was reflected in the Plan of Sustain‑ able Urban Mobility, is the development of electric transport, primarily tram traffic. The electric bus is a good thing, but it rides on rubber, and fine dust will be present in the air anyway. In cold time it will require a lot of electricity to heat the passenger compartment, or hydrocarbons will still be used. There is a strong industrial fac‑

Novopolotsk

Alber t Shakel

tor in Novopolotsk, and we approach the environmental issues very carefully. That is why we advocate for the develop‑ ment of the tram network, and we are in the process of negotiating financing for this purpose”.

— Th e economic situation in our cit‑ ies, aggravated by the pandemic, is un‑ likely to improve rapidly in the coming years — says the expert of the project “Green Cities” on the development of a plan of sustainable urban mobility for Polotsk and Novopolotsk Igor Pankov. — And it is necessary to develop in any case. Attraction of grant funds from interna‑ tional financial structures allows the cities to be on the go.

According to Igor Pankov, availability of such strategic documents in the city will greatly simplify the negotiation process with potential investors. —I am confident that our expert team will provide full support to city adminis‑ trations, which will decide on the need to develop strategic urban development documents — says the expert.

According to Igor Pankov, the most important thing is to understand that the city needs it: — It is necessary for city administra‑ tions to be more active, to search and ap‑ ply for grants which are allocated by the European Union, various international environmental organizations. The Nor‑ dic countries have a special programme. I assure you that if a city has a clear desire to develop a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, funds will certainly be available.

The expert urges administrations of Belarusian cities to actively participate in such an annual event as the European Mo‑

An example of artificial irregularities "speed cushion"

bility Week. Many Belarusian cities have been participating in this pan-European campaign for many years. And the num‑ ber of residential places participating in the European Mobility Week is constantly growing. It is a good occasion for the city to organise a dialogue with its citizens on topical issues. It is an opportunity to learn and adopt the best European practices. Be‑ sides, participation in the EMW allows to take a new look and rethink the condition and quality of the urban environment.

— Th e experience of participation in such a campaign always gives additional points when a city applies for funds for the implementation of infrastructure pro‑ jects, development of strategic urban de‑ velopment documents,— co ncludes Igor Pankov.

The EMW takes place annually from 16 to 22 September and ends with the cam‑ paign “World Car Free Day”. More than fifty countries of the world participate in the events dedicated to the European Mo‑ bility Week. By the way, last year 77 settle‑ ments from Belarus took part in it.

It should be stressed that the main goal of the campaign is to ensure sustain‑ able mobility of urban population, which should be based, first of all, on the devel‑ opment of public transport and the crea‑ tion of comfortable, safe conditions for pedestrians and cyclists. By Vladimir Mikhaylov

Dis cussi onson local topics

The Polesye State University hosted youth online dialogues of the UN campaign 75

The ancient city of Pinsk was the first to host the UN75 national dialogues in the framework of the infor‑ mation campaign “To‑ wards the future we want”, the launch of which was announced in Minsk back in March. More than 100 students and teachers of Polesye State University gathered online to listen to experts and discuss topics related to lo‑ cal socio-economic development, adap‑ tation to climate change, the use of inno‑ vations for emergency response. In each cluster, participants identified existing local problems and offered, often, nonstandard solutions.

Measures to improve the regional economy included proposals to estab‑ lish a business accelerator on the basis of the university to stimulate local small and medium business and motivation of youth entrepreneurship, development and piloting of new business ideas. By the way, for several years now an incuba‑ tor of youth start -ups has been success‑ fully operating at the university, which has more than one interesting business proposal.

Tourism was identified by the par‑ ticipants as another incentive for local economy development. The southern regions of Belarus are rich in natural monuments and are famous for their abundance of biodiversity. Creation of a tourist cluster of the Pripyat Polesye will help to develop a network of ecological routes, including also the Polesye Radia‑ tion Reserve, to create around them ser‑ vice infrastructure.

Climate change is already being felt in the southern regions of Belarus, i.e. higher temperatures, lower ground wa‑ ter levels, forest and peat fires. The par‑ ticipants voiced a number of interesting projects that will help to adapt land use practices, including degraded lands, to new climate conditions and to grow new types of agricultural products. Of par‑ ticular interest was the project on culti‑ vation of table grape varieties and devel‑ opment of the Belarusian wine industry in Polesye.

The topic of the emergency cluster focused on the use of innovation and digital technologies to respond to and prevent man -made, natural and medi‑ cal crises. The situation with COVID-19 makes it clear that there is a need to change the used technical approaches to respond to emergency situations, to change the approach to the purchase of special equipment and to the function‑ ing of enterprises. It is necessary to create dual-use technologies. As an example, a project was presented to establish a local ozonizer -p roducing plant, a technology that could be effectively used to control viral diseases both at home and on an in‑ dustrial scale.

The proposal to establish an infor‑ mational and analytical center on emer‑ gency situations in Pinsk, which would specialize in crisis forecasting and pre‑ vention, also aroused interest. All partic‑ ipants noted the importance of investing in innovation, building new partnerships and training specialists.

In the future, the continuation of the dialogue with the University of Polesye will be the elaboration of specific areas of cooperation to create an investment platform for the development of the ter‑ ritories of Belarus affected by the Cher‑ nobyl disaster. By Aleksey Fedosov

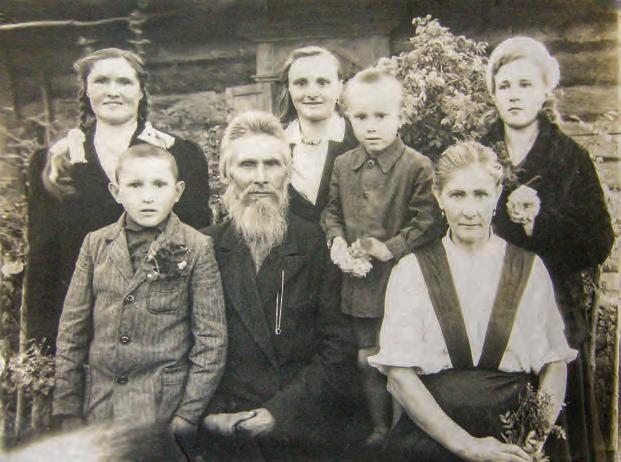

FFather, faher’s name, Fatherland… Respect for elders, especially parents, is a very important part of the Belarusian folk culture and national mentality. In the year of the 75th anniversary since the Vic‑ tory, we remember with special gratitude our fathers and grandfa‑ thers, mothers and grandmothers: both as great toilers who lifted p ost-war Belarus from the ruins and ashes, and as people of military glory. It is true that in the hustle and bustle of life it is not always possible to comprehend their great life experience. And to feel with the sixth sense a very priceless gene of the winners passed on to us as a legacy. Because sometimes it seems that we achieve every ‑ thing in life ourselves. And we do not even suspect that the invisible g ears and springs in the mechanisms of self-survival, were laid by our predecessors. Even without words or instruction, just by setting an example. Over the years, you catch yourself thinking: I’m doing something just like my mother or father did, I use their words and Irina and Larion Soroka. 1946. sayings… So Valery Soroka is convinced: life endurance and peas ‑ ant, hard working nature of his father are the essence of his personal‑ ity. And in life, both Sorokas, father and son, had to go through such w heels of fate that many, as they say, can’t even imagine. But let’s not get ahead of our feet. First of all, let me intro‑ duce Valery Soroka, with whom we talked about his masterful fa‑ ther and the experience that he passed on his son. Needless to say, we touched upon the important layers of life in the postwar hinter‑ land and the difficult path of a village boy, the son of a front-line soldier, to himself, to understanding the real, timeless values. To‑ day he is an entrepreneur, founder of the private unitary enterprise “AUM Soroko”. He rents out the premises built by himself in three

Built huts, made a garden and raised five children

Larion Soroka — a participant of two wars, a noble woodworker and a carpenter from the village of Skakunovshchina, which is in Beshenkovichi District of Vitebsk Region, made a good mark on the world. The example of his life inspires his son: a businessman, a member of the Union of Writers of Belarus. Father, having left this world, remains a patron of Valery. According to him, he comes to help in difficult moments even from the other world.

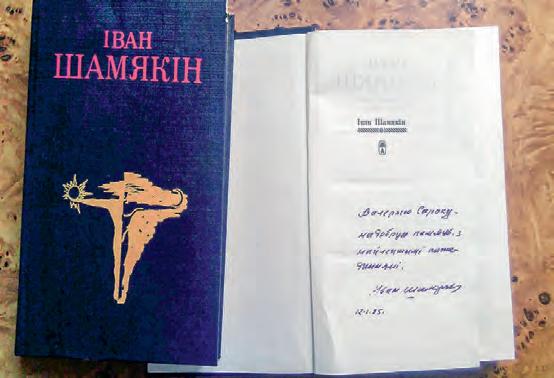

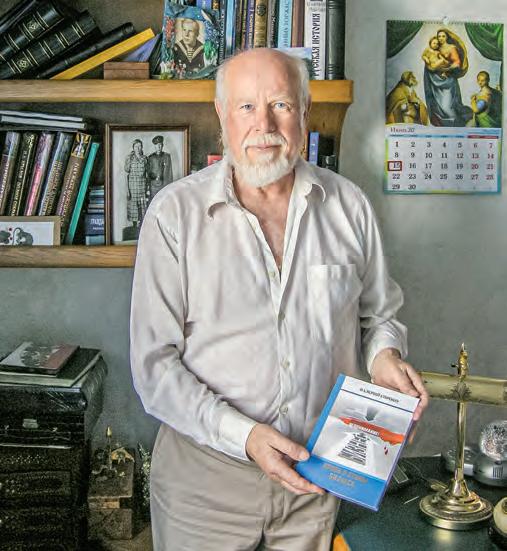

buildings near the famous Minsk Shopping Centre “Zhdanovichi”. In the village of Laparovshchina, near the Minsk Sea, he built a house for himself and rents out premises there, too. The employees of his firm also create documentary videos, which are posted on the Internet. Recently, a film “Partisans” has appeared on the web‑ site of Valery Soroka. But it is today. And in the Soviet past, a young public prosecution officer Valery Soroka got, as they say, “into hot water”: he became a victim of a political situation in his own pro‑ curocy system. It was a difficult period of the 80s, when the fa‑ mous Vitebsk case was being investigated, Perestroika was gaining momentum. He managed to endure, bearing in mind his father’s words: “Remember, son, to live happily means to live honestly”. Having recovered from the upheavals, he wrote documentary nov‑ els, for which he was admitted to the Union of Writers of Belarus in 1995. One of the references was given to him by folk writer Ivan Shamyakin. Now Valery Soroka is the author of 11 books. Some stories can be read on his website.

—Valery Illarionovich, what do you remember most from your village childhood?

— The smell of wood in our big house. All autumn, winter, one room was covered with chips, sawdust. Pine planks, birch, oak smelled… And the second bright memory — my father’s premade workpieces were hanging right under the ceiling. There was a big stove, above it wooden laths were attached to the ceiling. There were planks, bars on them. They were drying when the stove was fired. The father made of them window frames, doors,— the whole car‑ pentry for huts. Daddy had different wood-planes, workbenches,

axes, saws, chisels… I woke up and fell asleep to the sound of those tools: my father worked a lot. And the main thing is that he was an amazing man.

—In what way did it manifest itself?

—Larion Soroka was born in 1907 in a large family with many children, graduated from three classes of parochial school. At the time, for a village boy he was quite educated. He knew a lot of po‑ ems, even read them from memory. He used to work reciting po‑ ems, and I was listening. Everything was in Russian: the church education was in Russian. He recited Pushkin, Nekrasov, other classics. He told me, the deacon was a teacher at school. In the class there was a tseborok (bucket) with water, in it there were birchrods: so that they did not crack or break when used. God forbid you didn’t learn a lesson — you were thrashed right away. You behaved badly, made a noise, came to the lesson untidy — another thrash. This, I imagine, was very sobering for the students. It made them think, be alert all the time, not relax. And in this way the atten‑ tion was activated, everybody tried to learn everything and behave themselves: tseborok was always in sight. Dad said: everyone kept the noise down in class.

—Was your daddy strict himself?

— N o, he was good-natured, soft. I’ve never been hit in my whole life. Not once in my life! My mother could smack me, tell me off, and he never did it. I think it’s because he had been through a lot himself. After all, such people are not capable of nasty, mean things. It’s a different mentality. I remember, Maksim Gorky wrote: I was crushed a lot in life, that’s why I am soft. People who suffered many hardships, are not capable of sordid acts.

— Because they suffered and know what pain is like…

— … and fear. He understood what pranks are childish: and they are sometimes powerful impulses, bursts, emissions of the en‑ ergy of Life, which young souls simply can not cope with. He lived through a lot — and therefore was hardworking, kind, wise. It is hard for us to imagine, but he grew up in a family with 13 children! And since childhood everybody was got used to work, to live in a group, to be content with the little ones, to help others.

— And the craft, work with wood, who taught him?

— H e was self-taught. A handyman as they say. He also made leather and felt snow boots. We had sheep, bees, a vegetable garden of 50 hectares — a big farm. In honor of my birthday — and it hap‑ pened in 1952 — my father planted a garden. About 50 different fruit trees, in three rows to Lake Skakunovskoye. It’s right there. It was considered sacred, there was a church near it, and in the lake the Epiphany rites were performed. I saw in my father a great love for nature, animals, and people too. And as the years go by, I find that the most difficult thing in our life is to love people: everyone has their own character, worldview. So, I developed the ability to live in peace with myself, with others since my childhood. And I grew up in parental love.

— Did you have a large village?

—C omparatively large: 50 huts. There was its own shop, para‑ medical and obstetrical station, dairy factory — but it was gone in the 50s. And then the church was pulled down. With the wisdom of hindsight, I inderstand: the whole village community brought up a person, we absorbed its regular way of life, mastered its severe laws and rules. In the 30s my father was offered to head a collective farm: he was a literate one. He refused. Because he saw what was going on, he understood: a lot was required from the leader, and for faults one could get to no - so-distant lands. And he was not a com‑ munist: for some reason he treated them with suspicion, though he did not say anything bad. “People are different, and you have to understand everyone” — that’s how he explained it to me. But as a peasant, accustomed to live by his labor, to work on land, to have his own farm — he did not perceive collective work. However, like all normal people, who are used to living by their work, to cultivat‑ ing their land.

— A pparently, you have the same attitude towards collective farm labor…

— W ell, now it’s a different way of life, collective farms aren’t the same… But here I am analyzing the statistics: there are a lot of loss-making enterprises in Belarus according to the results of work for 2019. And unprofitable means ineffective. When there is no real owner, there will be no order anywhere, right? Everywhere you need a competent owner, and to develop your business effectively, you need to put your heart and soul, your strength and will. In order to make a profit — not only to consume what others have earned.

— L et’s go back to your father. Where did he serve in the army?

—In the building units, apparently. By the way, he made the first bath-house at the lake in the village — and people took turns to go there. For free. It was a good bath-house! And my father could stand the hottest steam, no one could compare with him: he was so strong and stubborn in this matter. Everybody ran away — he was taking a steam bath alone, and I lay down on the floor and added water.

—They say steam-bath is healthy. And how long did he live?

—I guess you can’t improve your health with steam-bath only. My father didn’t live long: 73 years. Maybe it’s because his life was

Valery Soroka (the youngest on the photo) with his relatives and mother. 1955.

hard. And his willpower was hardened, cast-iron. Once in early winter the lake was getting covered with ice, and a fellow villager in a sheepskin coat and felt snow boots went to it in a boat: to drive geese to the shore. The boat overturned, the man was under 70, he started to sink to the bottom. The men ran up, got into the water — it was cold! And father, he was 55 years old, swam up to the poor man, grabbed his hair, but did not hold him. Because, he said, he got entangled in his underpants. So he had to go to the shore, and the man was drowned. Dad was the only one who tried to save him. He never swam, though. But his willpower was cast-iron. He always tried the first ice on the lake. He made himself fit during the Finnish War, in 1939, when he was drafted. When they found out that he was a carpenter, they made him build river crossings. As soon as fighting burst out (there were sharpshooters) — he had to sink into the ice water, 10 times a day. Thank God, he came home without a scratch. And from that war he brought good planks, trophy Finnish chisels. And even a jack, 15 pounds of weight.

—Apparently, those were good tools…

— Of course! That metal didn’t become blunt. And my father also worked in summer: he made a canopy in the yard, and put his workbench there. Ac‑ tually, our house was kind of a collective one. At first, there was a school in it, then collective farm general meetings were held, service orders were given out by the foreman. And in the evenings men, especially in winter evenings, would gather for a sit -down. They set 5 tables, played cards, checkers. There was heavy smoke: home made cigarettes were smoked. My fa‑ ther was working in the next room, he did not pay much attention to others. He didn’t talk at all, listened more. And I was sitting on the stove, there was no air to breathe because of smoke. And I listened to eve‑ rything the men were talking about. And they talked about all kinds of things. Moreover, I quickly learned to play cards, and I was about eight years old.

— Fast socialization, as they say now…

—Very fast! And when there were not enough partners — they called me.

— Did Father tell you anything about his second war?

—Yes, I know it in brief. When the war broke out, he was draft‑ ed. He found himself in Western Ukraine, as a wireman. He told me: w e are pulling a wire-coil on the field — and a column of Germans is moving along the road. And another one: motorcyclists, tanks, cars… We dropped the coils and ran to the village. We jumped into the cellar, kept quiet. The Germans came and found us at once. They gathered 50 prisoners, placed them in the middle of the column and said: go in that direction. Two kilometers away there was a camp for several thousand people. Nobody abused prisoners of war yet. The Germans gave food and the local people brought food, too. And a fellow villager came to the camp with my father. They talked: what shall we wait for? They decided to run away at night. They managed to get to the woods, to the swamp: 10 kilometers away from the camp. And at dawn, they heard dog barking, submachine gun shots: they were chased. They crawled into the swamp: only their noses were sticking out of the water. The Germans fired at the swamp — the bullets were whining. One of them hit my father’s lip, it started bleeding. He bit it to make it bleed less. The Germans were gone. They were looking for fugitives, they knew: the weak surrender, the strong leave, if they are not caught — there will be resistance. Father said he’d stayed in the swamp all day. He stood up, called — no an ‑ swer. The man didn’t returned from the war: either he was killed in t he swamp or they found him. So death went by my father…

—Did he try to get to our troops?

— Y es, he did. He understood that he wouldn’t go far in a Red Army uniform. He asked some people to give him old clothes. He was walking home, covered about 25–50 kilometers a day, some‑ times he was given a lift. One of the villages gave him a pass of a refugee: an old woman advised him who to turn to. It took him almost a month to get home. He wore out three pairs of boots. There were three children in the family — my brother was born during the

Valery Soroka (front row, center) — sponsor of a number of performances by Minsk Folklore Thea tre "Matulina Khata"

war, and I was born after it. My father started living in the village. And someone informed that a soldier had returned home: there were such people. Opposite our house there lived a neighbor, also Soroka, the headman. When the Germans and the police entered the village, my father rushed into the barn and buried himself in straw in the attic. They asked the mother: Where is the husband? Mother: I do not know, I have not seen. They drove her outside and put against the wall: we’ll shoot you down, say. The father was lying in the straw, he heard the conversation. He stood up and was ready to get out, he was going to give himself in — he felt sorry for his wife. And he heard the voice of the headman, his neighbor: do not touch her, she has three children. They fired above her head and left. Although the father survived, but it was a real hair - raiser for him. He understood: it was necessary to run away. He joined the partisans. And when the Red Army attacked and liberated the vil‑ lage in 1944, he went back to the front. Mother in the same year re‑

ceived a death notification, which said that the father was killed in caught me, but I didn’t want to hug her. Only at night, I remember Lithuania. The name of the farm near which it happened was men‑ thinking: can she really bo my mother? In the morning I woke up tioned. Later my father told me that the fights were very heavy, and I looked at her trying to remember: are you my mother or not? 15 people stayed alive from his company, a hundred soldiers. And My mother was awake, her eyes were closed. She felt her son look ‑ the commander was a brave lieutenant, a Jew: forward and forward. ing at her. And said quietly: my little son… Ouch, I remembered, We must attack! There was no tactical strategy. No one, he said, a nd rushed to her: “Ouch, Mom!” I recollect such moments — they cared about soldiers, how many of them could die. The commander touch my soul, give strength. More than once they helped me find with the gun ran in front, they followed him with rifles. That’s how my balance of mind when I was going through hard times in my life. they were running, and were surrounded. Most of them were killed, —Did your father teach you his carpentry craft? were killed, the others had to raise their hands, 5–7 of them. — S ystematically — no. I helped him with something, of —It was, apparently, in the summer or spring of 1944? course: held, carried, fetched something. He was nearby, I saw his —Yes, after the liberation of Belarus, the Red Army was mov‑ work — and it brought me up. And some skills remained for life. ing to Lithuania. He was imprisoned for the second time. In awful Of course, like any villager, I know how to use many tools nec‑ co nditions! People there were dying of hunger, of cold. I don’t know essary for farming. In addition, my father did carpentry work in where exactly: I was too small when he told about it. But even there, winter (windows, doors, panels, different decorations), and as soon the father managed to adapt, to survive. He as a warm season began — he went away could make boots, shoes, mend clothes. A In the Internet database “Memory of with an axe, to make huts. And, in fact, he German brought him shoes to repair — and the People” we managed to find rebuilt our village in the postwar period. gave some bread for work. Soldiers, privates some documents that refer to the And in neighboring villages the log huts from both sides knew how to adapt to mili ‑ father of Valery Soroka. He made by him are still standing. He worked tary life. The father even managed to feed fought in the 71st Guards Rifle alone, without other workers. The helpers o ther people. By that time the Germans’ Division, the date and place of were the owners of the hut. There was even ammunition had been worn out, there were conscription are as follows: a waiting list. no reserves. In this way he managed to sur‑ “29.06.1944, Beshenkovichi RMC, —F irst, I know, you need good wood, vive — in Lithuania, and somewhere near Belorussian SSR, Vitebsk Region, it should be stored in dry premises — and P oland, as he said. When they were released, Beshenkovichi District”. Larion then they made a log hut… everyone was checked at once: a special in‑ Borisovich Soroka, born 1907, the — W e did everything in the correct spection. It lasted up to a year. They were Red Army Guard, shooter of the way. Everything was discussed, prepared, s tationed in a special company in Lithuania. 213th Polotsk Guards Riflemen deadlines were set. For example, people They were suspected of connections with Regiment, was awarded the medal stripped logs of bark, and the father did the Germans. Six months passed after the “For Bravery” by the order of professional work. Usually the father was end of war, and there was no news of him. 16.09.1944, and by the order of absent from home for 2–3 weeks, he worked Mother was about to go to his grave. Father 09.05.1945 — the medal “For from morning till night: to make the house said that there were witnesses who said: it the Victory over Germany in the ready to move in, as they say. And we, the was survival, a struggle for life, and that Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945”. kids with Mom, did all the housework. The they survived thanks to him. They let him huts were built by those who had money. go. And meanwhile there were award lists, medals in the military Either they had cash, or their children who lived in town, nephews, committee waiting for the hero at his place of residence. relatives helped. Dad was paid for his work in cash. And he was so

Once, already in 1946, he called the village: I’m alive! Everybody kind, he didn’t charge much. As much as people could afford. They became numb. He came back, started to work as usual, raised the were all poor back then. household: we had a cow, pigs, sheep, bees… It’s true that my mother — Weren’t the collective farm managers against that he was did most of it, and we helped her, and he did carpentry work. At doing it? that time, money was not paid at the collective farm: workdays were —No, because everyone knew: he had skillful fingers. And peo‑ counted, ticked. According to them people were given grain, meat. ple needed huts. When the construction was over, they celebrated it There was no cash at all at first, and life went on, which was not easy. b y drinking a lot. And my father, though strong, was not tall, thin, Let’s say, I was born in 52, and in 54 my mother — Irina Alekseyevna, besides every day did hard work. Well, it so happened that he couldn’t her maiden name was Kovalenko, born in 1913 — got seriously ill: stand after it. I remember him being brought in a cart, “unloaded”. she had meningitis. She was brought to Vitebsk, and operated on. She Mother often swore at them: what are you doing? I need a man who’s stayed in hospital for 6 months. When they brought her home, I was healthy, and you have brought me a cripple! And we helped to bring two and a half. In mother’s absence, my elder sister Zinaida looked him into the hut, to put him to bed. My dad recovered from it, and after me, as well as the whole farm. And I became estranged from her. headed out again. By the way, he never smoked when he was sober, They said: it’s your mother and I didn’t understand or recognize her. only when he drank. He always had a pack of cigarettes, treated eve ‑ I said: she’s some aunt. Go and give her a hug, and I ran away. They ryone. He was so friendly, sociable, and never drank alone.

—Did you have vodka in your hut?

—Of course! How could we do without it in the village? And a lot of people, it’s no secret, made moonshine. And there were 2–3 moonshine stills in the village, they were passed round if necessary. I remember, I was about 5 years old, a policeman, with whom my father was on friendly terms, came to our house. He sat down at the table and asked: Do you have moonshine? Everybody was silent: the policeman, however, was in uniform. He came up to me: tell me, do you have moonshine? I said, “I’ll tell you if you let me hold your gun. He took the gun out of the holster, took out the ammo: here you are. I held it. What a pleasure! I was holding a real gun in my hands. I was going to tell the whole village about it. I said with joy: There’s moon ‑ shine. Where is it? In the wardrobe. There were a couple of bot‑ tles among the clothes, he took them out and said to the father: C ome on, Larivon, let’s have a drink. What are you afraid of? They drank, and went about their duties. And my dad didn’t even reproach me for what I had done.

—Apparently, he knew child psychology well. He understood: it was not because of malice, an innocent child. And what did he want you to be, what occupation?

— I do n’t think we’ve had this kind of conversation. But as I grew up, I tried to study well. I under‑ stood: otherwise, I would have to stay in the village, and there was hard work from morning till night. I want‑ ed to study, to get a higher education. I read a lot, I was an avid reader. Even being a primary school pupil — in the evenings by torch, with a kerosene lamp. And there was shortage of kero‑ sene. I used to stay up reading until midnight. My mother made me go to bed — and I couldn’t stop. It was interesting! My parents got tired, they could only reach the bed.

—What subjects were you good at?

—I was good at math. And other so-called practical subjects. At first I studied at our village school, then I had to go to Bo‑ cheikovo 9 kilometres away to get a secondary education. 18 km a day! There were two of us. Frost, cold, snow, rain, slush — we would go. Sometimes we were given a lift, if a car went along the road. We walked fast. We managed to cover the distance for an hour and a half. And we both learned quite well, by the way. Because we knew that in order to enter the university, we had to study well. And I had a desire to enter the law school. Actu ‑ ally, my cousin was a policeman, he came to us and told us a lot o f things. And I gradually developed a craving for this profes‑ sion: justice, law and order. I also wanted to be a policeman. In t he ninth grade I already knew: I would work for the police, or for public prosecution. And my friend, Alexander Kanapelko, became a military helicopter pilot, served in Russia. Now he is

living in Vitebsk: he has a house there, we are in touch. All school years we were side -by-side with him.

—Listening to you, Valery Illarionovich, I understand where your gift of a narrator come from…

—Yeah, I’ve talked to a lot of people in my life since I was a kid. There was a “hobby club” at home: it must have influenced, too. Well, now so much has been experienced, seen and heard that I want to share it with others. On the road of life we absorb every‑ thing — and then it wants out.

—They also say that what happens to us in the outside world only helps to awaken what we have inside. After all, our life energy comes from inside, and if a talent is given by God, as they say, it will awaken.

—Well, maybe. After all, it is one thing to chat sitting on a bench, and quite a different thing to experience something important, to write a book about it. And I wanted to comprehend deeply everything that had happened to me, to tell my truth, to be heard — so I started writing. In fact, I went into business for the same reason: to be able to publish my documentary books. After all, as you know, it requires money. Some more words about a talent, abilities. I remember one of my father’s brothers, my uncle. The villagers used to get together at my grandfather’s to read books. So the next day my uncle could retell every ‑ thing — almost verbatim. H e had such a unique mem‑ A n aut ographed book by Zh I v an Shamyakin ory. And my elder brother ora, who died at the age of 12, wrote poems. By the way, there was another girl in the family, a year older than Zina. The children in the house were alone during the war, a fire broke out — and the house caught fire. So, my father and mother had five children, but raised only three.

—And you probably, know the whole penal code by heart, don’t you?

— (smi ling) Well, not the whole: the years are taking their toll! Sometimes I can’t remember what happened yesterday. (laughing) Especially when you’ve been through so much. Once a traffic cop stopped me in Minsk — I said: Captain, I am law -abiding, a for‑ mer prosecutor myself. Soroka is my last name. Maybe you have heard it. I have, he said.

—So, did you enter law school right away?

—Not right away, after serving in the army. I didn’t enter it at first, I graduated from metallurgical school in 1970 and started to work at Kirov Factory. Then joined the army, the navy to be exact. When I was in a training center in Kronstadt, I was trained to be a submariner, strong boys were selected for a sport company. And I was a boxer, had the first category — so I was selected. I did well at the championship of the Northern Fleet, in 1972: I was among the winners. But then I had appendicitis out, it was peritonitis with exac ‑

erbation, it took me long to recover, I lost my fitness form. The fleet didn’t need such an athlete, and as a sailor I was no good. Anyway, I was freed from military service on medical grounds. And already in 1973 I was studying in Moscow, at the Peoples’ Friendship University named after Patrice Lumumba, but quitted it because of material dif ‑ ficulties. I went back to my factory, worked as an electrician on duty, wa s a tutor in a dormitory, and a year later as its manager. In 1974, I entered the part-time department of the BSU law school. In 1977, I began working at the public prosecution office of Minsk Region, as an assistant prosecutor of Slutsk inter - district prosecutor’s office. At that time my father was under 70, and he fell ill: he couldn’t eat. I took him to the doctors, his diagnosis was stomach cancer. A month or two he can be kept on an IV, they said. So what to do next? Some people advised: it is necessary to take mutton or beef fat, it was called loy, to melt it. To drink pure medical alcohol, and then to drink warm loy. For a day or two my father was treated in this way — and he began to eat. Alcohol burns the cells, and loy heals them immediately. Dad lived with that disease for four more years. He died in 1981.

—And how did he feel about the fact that you became a prosecutor?

—He was worried about me. Apparently, his life experience told him that I was going through some serious trials. He told me once: “Son, you shouldn’t have taken this job. It’s an ungrateful thing to imprison people. You will not be forgiven. You can’t do bad things to people.” But what if these people committed crimes? I did not ask him this question, but knowing what a kind soul my father had, I can assume that he would answer.

— A pparently, we need to listen to the opinions of people who have life experience, let alone the parents — and not even argue with them.

—Well, that is the conclusion I’ve come to over the years ana‑ lyzing everything that’s happened to me. But the most interesting exp erience, related to my father, was when I was detained, suspected of illegal actions and abuse of power, put in the Minsk detention center of the State Security Committee. I was in deep trance, in great depression. Just imagine: a prosecutor suddenly becomes a convict. Imprisoned. And a solitary cell is like a coffin. I calculated the dis ‑ tance between the walls: 8 and 16 of my size 42 shoes. It’s like a 3–4‑m eter - long pencil case. The walls are black. There is a plank-bed on the wall, which can be used at night. And silence, as if you are lying in a coffin. There’s no information. The walls are thick, they don’t outlet a single sound, only at the top there is a small air hole —Speleologists told me: for scientific purposes they conducted physiological experiments in caves, in the confined space, in the dark, where there are no external stimuli. It’s called sensory depri‑ vation. So, they said, it is psychologically difficult for people to bear, and after it different physical health problems can develop. —Yeah, it’s psychologically stressful. And I had thoughts about committing suicide. I thought: how can I look people in the eyes if I am convicted? It’s such a shame! My psyche couldn’t stand it — it was a mental breakdown, even though I’m a tough man. I was already thinking about the way to do it. To stand on the table, and tie a sheet to window bars? I lay thinking it over. And every three to five minutes

ch i v ano

zhd an Iv

Valery Soroka with one of his books

a peephole opened and closed. The guard went around the cells and looked so that nothing of what I was planning could happen. In the morning, it didn’t open often, the duty officer got tired. Well, I de ‑ cided I would do it at five o’clock in the morning. I was lying, waiting f or dawn. I couldn’t sleep. And suddenly my father came to me. He sat down next to me, in a dark suit. He said: “What, son, is it hard for you?” “Yes, Father, it’s hard,” I told him. He said, “You’re in trouble. But you’re going to be all right. I’m telling you the truth. “How, Dad, can it be okay? You are kidding me!” “No, son, think well. Sit and think it over. You’re gonna be okay. And I’m leaving.” “I want to leave with you! I’ll go with you!” “No, you stay here.” We had a few more arguments, and he left. I came to my senses and couldn’t understand: what kind of dream it was? My mind worked clearly. Dad was here. The dream was uneasy, nervous, my nerves were tightened like strings — and sud ‑ denly there was a dialogue with my father: you stay here and I’ll leave. Th at’s when I thought: what if my father came on purpose to save me? — You know, parents are our patrons. In the Slavic world‑ view it is considered that parents, leaving for another world, be‑ come gods of a kindred — they invisibly patronize those relatives who stay on the earth. So, you got a very timely support… —Yes, I came to the conclusion: I must fight. Because my en‑ emies, who started a dirty game, wanted to drag me into it, they counted on my weakness. And a suicide would be their victory. And in a difficult moment, my father came to me from the other world, supported me. And thanks to that I survived, I managed to overcome all the trials, to regain my feet, to write my books. And now I’m talking to you today. So, my father, a front-line soldier, an honest country worker, Larion Soroka, is still with me. Interviewed by Ivan Zhdanovich