9 minute read

When the approach is highly professional

Despite the spread of coronavirus infection, N. N. Alexandrov National Cancer Centre continues to treat patients with cancerous tumours. They now see patients from almost all over the country. How has the coronavirus affected the cancer service and should we expect a surge in new cancer cases when the pandemic is over? How are cancer patients coping with COVlD-19? When will early detection programmes resume and who will be the first to be screened for stomach and lung cancer? About this and other issues we speak with the deputy director for scientific work at N. N. Alexandrov National Cancer Centre, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Corresponding Member of the National Academy of Sciences Sergey Krasny.

— Sergey Anatolyevich, how did the spread of COVID‑19 affect the diagnosis of cancer, the work of the Republican Sci‑ entific and Practical Center for Oncology and Medical Radiology, and the behavior of the patients themselves?

Advertisement

— This is definitely a big problem. The spread of coronavirus infection affected the work of the entire oncological

ANNA ZANKOVICH service. First of all, many oncological dispensaries in the country were repurposed — partially or completely — to provide care to patients with covid infection. Accordingly, cancer patients who were to be treated there were redirected to us. But this did not overload our center. Now we always have vacant space, as the number of cancer patients

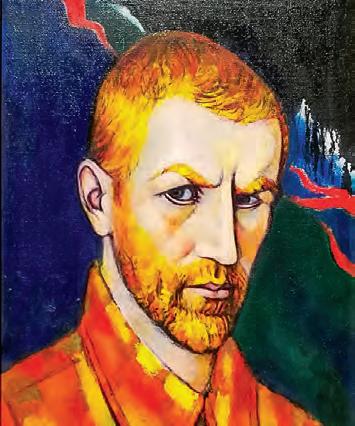

Oncologist Sergey Krasny coming for treatment has significantly decreased.

This is due to two factors. Firstly, at the initial stages of malignant tumors, most often there is no need to provide urgent assistance. These tumors, as a rule, progress slowly, and in 1–3 months the health status of these patients will not change significantly, so we can wait for a decrease in the incidence of coronavirus infection and treat them in spring or summer. Secondly, polyclinics and district hospitals are now working with great overload and provide care mainly to patients with COVID-19 infection. Naturally, they cannot engage in routine care, including the diagnosis of malignant tumors, screening has completely stopped. Accordingly, the number of diagnosed cancer patients has decreased. Therefore, there is no large influx to our center.

We fully cope with those patients who come to us. Hospitalization is very strictly organized here: everyone must have a negative test for coronavirus infection. In addition, before hospitalization, we do all our patients a computed tomography of the lungs, because even with a negative analysis for COVID-19, cases with asymptomatic pneumonia slip through. After all, PCR analysis, unfortunately, is not 100% accurate. In addition, it is valid for several days, during this time a person can get in-

fected. People may undergo an operation, and after that the symptoms of the disease appear — such cases, unfortunately, also happen. Such a patient can infect a roommate or medical staff.

Some of the staff at our centre have either been ill or are currently ill. This also causes some difficulties, but we are used to them. The centre has developed a system for dealing with COVlD-19. Patients who are diagnosed with the infection are immediately transferred to the appropriate specialized institutions, except in cases where they require urgent oncological care. For this, we have a specialized department — isolated, with a red zone. And there we provide care for patients with a combination of cancer and coronavirus infection.

I would like to take this opportunity to say a word of thanks and admiration to all the medical staff who, in these difficult times, are working hard to save our patients without sparing themselves. Believe me, that courage and heroism towards them are not pathos words, but a daily reality.

— How do oncology patients cope with COVlD‑19?

— As knowledge is being accumulated about the combination of coronavirus infection and cancer pathology, some rather interesting things are emerging. It would be logical to assume that cancer patients would be sicker and more difficult to tolerate this infection, as it is generally believed that their immune defense is lowered. But it turns out that in some malignancies COVlD-19 either does not affect these patients at all, or, if they do become infected, the disease is mild. An example is B-cell lymphoma, where the function of B-lymphocytes is severely impaired. They do not perform their protective function of producing antibodies. And in coronavirus infection, this is extremely important in terms of the development of a hyperimmune response or cytokine storm. Thus, it cannot in principle develop in patients with lymphoma due to insufficient functional capacity of B-lymphocytes.

Recently, it has been found that patients with advanced prostate cancer receiving hormone therapy also either do not get it, or get it in a mild form. Apparently, the blockade of hormone receptors crosses with the receptors through which the COVlD-19 virus acts. They also have a mild form of the disease.

But in most cases, cancer patients get ill quite severely. Because they are usually elderly people with weakened body. That’s why we put up all the barriers that we can, so that the infection does not spread inside the centre.

— You said that screening activities have now been halted. Can we assume that if the coronavirus infection is on de‑ cline, we’ll get a surge in cancers?

— This won’t happen because of the stopped screening. Screening programmes are aimed at healthy people or people who think they are healthy. They are usually diagnosed with stage 0 or 1 during screening. It may take months or sometimes years before the second stage develops. In stage zero (the so-called precancerous stage), the disease develops very slowly. Therefore, no harm will be done because of the stopped screening programmes for a few months,

As for the routine diagnosis of malignant tumours, when people go to the doctor with complaints, there can indeed be a problem, because now, unfortunately, the provision of routine care has been temporarily discontinued. And these patients tolerate, even though there are symptoms, and are not examined. And this can have serious consequences: if they come to the oncologist in six months’ time, they may have advanced malignancy. This is a serious consequence of the COVІD-19 pandemic, a problem that I think is common all over the world. And in a year or two, it could lead to increased mortality from malignant tumours.

— Besides the four known screening programmes for cervical, prostate, breast and colorectal cancers, perhaps others will appear?

— If the incidence of coronavirus infection decreases, screening projects will continue in all four above mentioned. Apart from that, I think the pilot project for gastric cancer screening will be over by then.

BELTA

In the first stage, serological tests are performed on patients: blood tests are used to examine the volume and ratio of pepsinogens and the presence of helicobacter. If these factors are present and we see that the risk of malignant tumour or atrophic processes in the stomach is high enough, a gastroscopy is performed. And among the patients who undergo gastroscopy either tumours or pre-tumoural processes are detected quite often. They are given targeted treatment. So the pilot project has shown quite high efficiency, and we hope that when the situation stabilises, we will expand the screening programme for this localization.

The lung cancer project has been under way for a year and will last for five years. Patients are given low-dose CT scans, and quite often lung masses are detected at an early stage. These are removed and this reduces the mortality rate from lung cancer.

— Who gets into the gastric cancer and lung cancer screening programmes?

— For gastric cancer, the target audience are those who have symptoms of the disease. But by and large, those who are more likely to have these tumours should be tested. As a rule, these are people over 40, smokers are also included here. After that, the age range will widen and will include those who have a genetic predisposition, i.e. if their relatives had the same disease.

With regard to lung cancer, only smokers fall into the risk group, with a long history of at least 15 years. There is a special formula for calculating this: 15 years of smoking a packet of cigarettes a day. If you smoke two packs a day, you don’t have to wait 15 years — the disease develops faster. At the end of the pilot project, conclusions will be made as to how effective it is for our country and whether it can be used. It is not cheap, as it requires expensive equipment. But misfortune helped. Due to the spread of coronavirus, appropriate CT scanners have been purchased, which will be more available in a quieter period and can be used for CT scans of the lungs of smokers. Hopefully the pandemic will be over before the project is completed and we will introduce lung cancer screening.

— Does the liquid cytology method, which was supposed to replace the previ‑ ous cervical cancer smear, work?

— While there are no screening programmes, it is used for routine diagnosis. During the transition period, all women were screened using both methods in order to train both cytologists and gynaecologists, because both the system of taking material and preparing smears are completely different. Now the training is over, and if COVlD-19 is on decline, it will be possible to use liquid cytology more widely.

— What should people in their 30s and 40s check?

— As for malignant tumours in the 30s, nothing, except cervical cancer, because it has become dramatically younger. It’s linked to the spread of papillomavirus infection. And due to the earlier sexual debut (it is not uncommon to have it at the age of 12–15), we now have 25 and even 20-year-old women who have cervical cancer. If the body’s defense system is weakened, the tumour may develop not in 10 years’ time but even faster. For this reason, cervical cancer screening is carried out on a large scale from the age of 30. In general, a woman should visit her gynaecologist on a regular basis from the beginning of her sexual life and the doctor will decide when she should have a cytological examination.

As for all other malignant tumours, they are quite rare at a young age, so there is no need for targeted screening in this case.

From the age of 40 onwards, however, more serious health problems arise, so it is necessary to join various screening programmes. Depending on their age, we include these patients in breast cancer, prostate cancer and other screenings.

— But can it happen that a person feels well, and from time to time he/she does some tests, for example, a breast ultrasound, visits a gynaecologist, and then he/she is diagnosed with stage three cancer?

— It can also happen, but it is less likely than for those who do not go to the doctor and are not examined, and wait until they get sick. Naturally, no matter how many diagnostic methods we have, none of them are 100% effective and both falsepositive and false-negative results are possible. Either one is no good. A patient is diagnosed with a suspected malignancy using one method or another, and the diagnosis is corrected during the follow-up diagnostics. But the patient is psychologically traumatized and has a certain fear for the rest of his life. This is the disadvantage of screenings. Such cases occur quite often, but you have to be prepared for this when you go for screening, and not to panic.

False-negative results can also occur when the tumour is small and the separability of the method does not allow it to be detected. And then the patient shows up in two years’ time for the next stage of screening, and the tumour is found, or within two years there are symptoms — this is the so-called inter-screening cancer. Unfortunately, these situations do occur, but much less frequently than among people who are not screened at all. By Elena Kravets