5 minute read

The Big Picture

IN ADDITION TO BEING A BUSTLING CENTER OF SHIPBUILDING, MANUFACTURING, AND TRADE, BELFAST WAS ONCE A MAJOR CENTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Advertisement

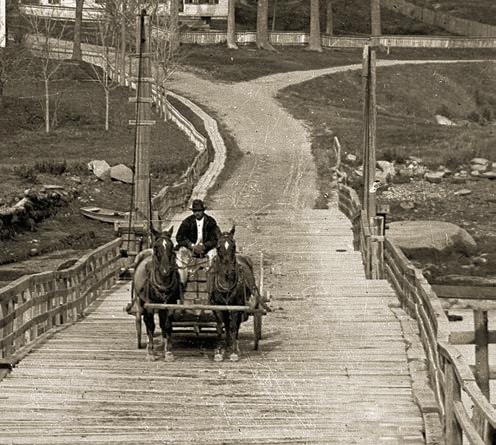

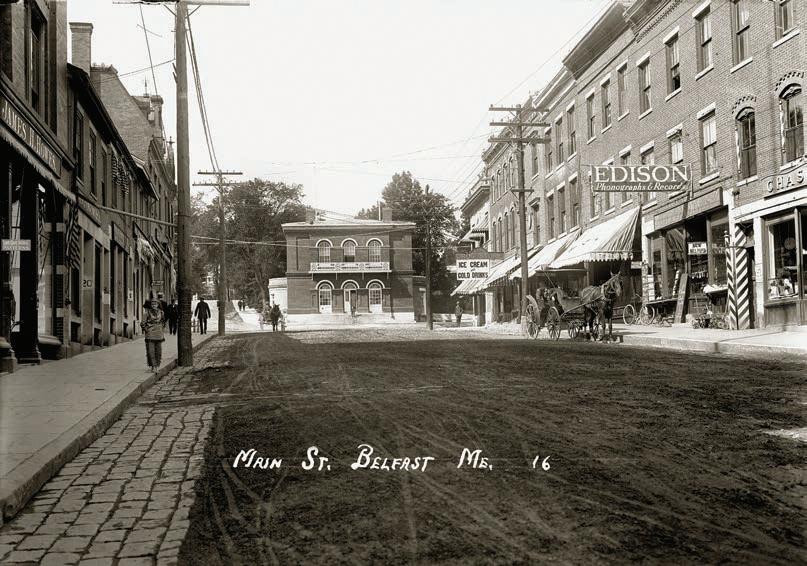

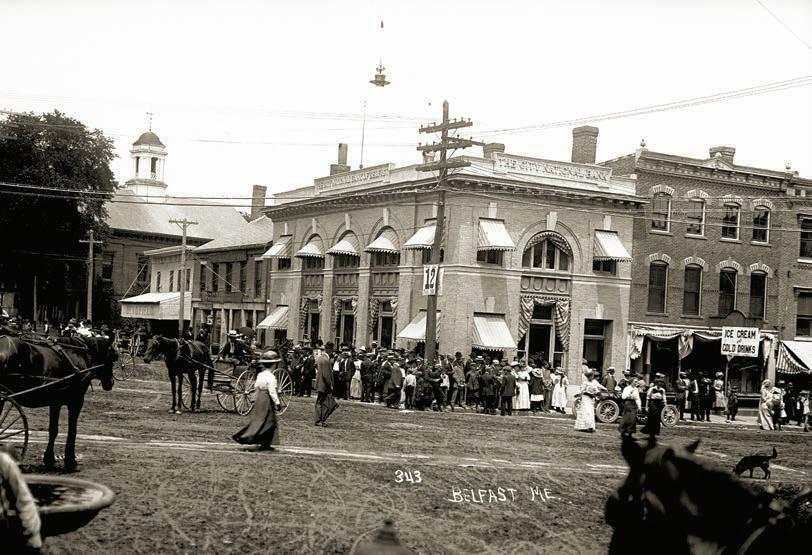

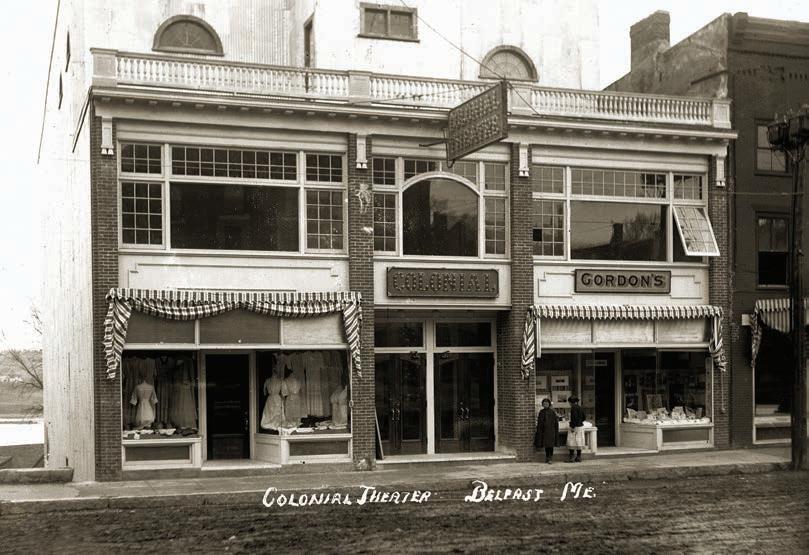

At the dawn of the 20th century, Belfast was a bustling center of business enterprise. Downtown was filled with factories turning out clothes, axes, window sashes, and a panoply of other goods. Another industry was also burgeoning here: real photo postcards.

At the time postcards were as prolific as the texts and tweets we fire off today. Most postcards were mass-produced by print houses in Europe, and “real photo” postcards were emerging as a premium item.

At least three photographers were making real photo cards in Belfast, and in the offices of the Waldo County Herald, Rudolph Herman Cassens launched the Eastern Illustrating and Photography Company which would become the country’s largest maker of real photo postcards and produce an unrivaled visual archive of life in the early 20th century.

Each spring, as soon as the muddy roads were hardened enough to drive on, Cassens would dispatch photographers to capture people, landmarks, landscapes, parades, and scenes from everyday life throughout New England.

The photographers travelled the countryside in Model T’s and used 5-by7-inch box cameras with dry plate glass negatives to capture the scenes. They’d ship the negatives back to the Eastern Illustrating offices which eventually moved to the building on Church Street where the American Legion Hall sits today. There, a staff of 20 women and girls would print the negatives to paper and label them, writing backwards with white ink, so that when the images printed in reverse, the letters would read left to right. At its height, Eastern Illustrating was turning out 1 million real photo postcards a year, and by the time Cassens sold the business in it had produced 75,000 negatives.

Kevin Johnson, Penobscot Marine Museum

“Because of what he did, we have this amazing archive of life in early 20th century New England says Kevin Johnson, photo archivist for the Penobscot Marine Museum, in Searsport, which holds 50,000 negatives from the Eastern Illustrating collection.

But it’s not just the volume of the photos that’s remarkable, Johnson adds, it’s their quality and resolution. Because the negatives were 5 by 7 inches, in contrast to a modern 35mm negative, which is about the size of a postage stamp, when you zoom in, the image remains sharp and clear, and one can decipher facial expressions, license plates, details of clothing and accessories, posters, and advertisements.

The effort to archive the Eastern Illustrating photos has been a 15-year odyssey for Johnson. Some 35,000 of the negatives were sold to a series of owners and ultimately donated to the institution that is now Maine Media Workshops. In 2007, after a pipe burst in the basement where they were being stored, Johnson, a workshop employee at the time, worked alongside fellow students to dry them out. Ultimately, the negatives were donated to the Penobscot Marine Museum, where they remain today.

Since that time, Johnson, along with an army of volunteers, has been working to archive, catalog, and digitize the collection, and he has led the effort to track down some 15,000 negatives that went missing from the collection over the years. Many of them have ended up in the hands of collectors and antique dealers.

Selections are on view at the museum and also online. Along with the archives of National Fishermen and dozens of other collections, Penobscot Marine Museum has one of the state’s largest archives of historical photographs, with more than 300,000 negatives, prints, slides, postcards, and daguerreotypes, plus 140,000 online. Johnson is driven by a passion to properly preserve and share the collection and complete this historical record, and also try to capture as many stories as possible that the photos depict from the people who were alive when they were taken.

Visit the Penobscot Marine Museum

40 East Main St., Searsport. 207-548-2529. penobscotmarinemuseum.org