When URL Meets IRL in Web3:

Lessons for Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies in Democratic Governance

Helena Rong

Helena Rong

Helena Rong

Helena Rong

First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the late Secretary Ash Carter, for his unwavering support and invaluable guidance in the Technology and Public Purpose program. His steadfast dedication to technology and public purpose serves as a continuous inspiration for carrying the torch forward.

I would also like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to our TAPP Associate Director Amritha Jayanti for her inspirational leadership during times of crisis and constructive feedback throughout this project’s development, our TAPP Project Coordinator Victoria Burnham for her generous assistance and uplifting presence, and Professor Venkatesh “Venky” Narayanamurti for his support of the TAPP program. Gratitude is extended to my entire TAPP cohort Sarah Hubbard, Conrad Kramer, and Luca Giani for their encouragement, valuable input, and warm friendship. I also thank the rest of my colleagues at TAPP and Belfer Center John Schultz, Ariel Higuchi, Ada Ezeokoli, and Liza Xiao for their camaraderie and support.

I would also like to express my gratitude to my PhD advisor Professor Weiping Wu, and my PhD prospectus defense committee members Professor Anthony Vanky, and Professor Xiaobo Lu for their insightful feedback and suggestions on my PhD proposal which helped shape part of this research.

I am beyond grateful to my stellar team of research assistants, Zeslene Mao, Er Li Peng, David Dam, and Elena Jin for their hard work and invaluable contribution to this research. I also thank all the interviewees who generously shared their time, knowledge, and perspectives on the selected case studies with my research team.

I would like to thank Professor Alex “Sandy” Pentland, Professor David Wood, Professor Mitchell Weiss, Dr. Shirley Jackson, Finn Xu, Xenofon Kontouris, Connor Spelliscy, Vasu Nigam, Scott Moore, and colleagues from MIT Connection Science for providing feedback on parts of this work, particularly on the proposal for fractional property ownership and collective governance in local development that was published earlier this year.

I am grateful for the opportunity to teach the class on “Technology, Trust, and Governance” at the Harvard Graduate School of Design this spring. I thank my

wonderful co-instructor and collaborator Professor Eric Gordon, and all twelve MDes students in our class, our reviewers, as well as our guest speakers for the class. Our discussions and engagement have been inspiring and continue to influence my thinking about this space.

I am also grateful for the chance to collaborate with Professor Justin Hollander and the fantastic team at Tufts University on the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation-funded project in the town of Swampscott, where we could test some of the ideas related to this research in a real-life setting. My gratitude goes to Pete Kane and Marissa Meaney for providing us with the opportunity to collaborate on this project.

I am thankful for working with Sarah Hubbard on organizing the “Perspectives on Web3” virtual panel series last fall and with Eduard Peris i Deprez on putting together the “Harvard Blockchain for Impact Workshop” this spring. My gratitude goes to all our panelists, speakers, and attendees who help deepen my understanding of this evolving landscape.

Last but not least, I am also thankful to numerous academics, practitioners, and friends who took interest in this work and generously shared their time and insights with me at different stages of this work’s development. This includes Stephen Larrick, Rebecca Williams, Professor Graham Allison, Cara Eckholm, Mike Bloomberg, Charlie Stigler, Sheng-Hung Lee, Maxwell Kanter, Yan Ma, Zixiao Yin, Liz Sisson, Aviv Ovadya, Joshua Cheong, Ian Cain, Leila Collins, Professor John Haigh, and Tim Massad. I also appreciate the exchange of conversations with Dr. Glen Weyl, Joseph Lambke, Professor Anthony Zhang, Madeleine Daepp, Nneka Sobers, Josiah Tullis, Professor Adele Santos, Doug Calidas, William Gao, Cyrus Hodes, Li Sun, Juncheng Yang, Michael Cooper, Dr. Primavera De Filippi, Dr. Shlomit Wagman, Joshua Tan, Eugene Leventhal, Hazel Devjani, Professor William Riggs and Professor Vipul Vyas.

To all those who have contributed to this project, either directly or indirectly, thank you.

Research Assistants Who Contributed to this Report: David Dam, Zeslene Mao, and Er Li Peng.

The arc of innovative progress has reached an inflection point. It is our responsibility to ensure it bends towards public good.

Technological change has brought immeasurable benefits to billions through improved health, productivity, and convenience. Yet as recent events have shown, unless we actively manage their risks to society, new technologies may also bring unforeseen destructive consequences.

Making technological change positive for all is the critical challenge of our time. We ourselves - not only the logic of discovery and market forces - must manage it. To create a future where technology serves humanity as a whole and where public purpose drives innovation, we need a new approach.

Founded by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, the TAPP Project works to ensure that emerging technologies are developed and managed in ways that serve the overall public good.

TAPP Project Principles:

• Technology’s advance is inevitable, and it often brings with it much progress for some. Yet, progress for all is not guaranteed. We have an obligation to foresee the dilemmas presented by emerging technology and to generate solutions to them.

• There is no silver bullet; effective solutions to technology-induced public dilemmas require a mix of government regulation and tech-sector self-governance. The right mix can only result from strong and trusted linkages between the tech sector and government.

• Ensuring a future where public purpose drives innovation requires the next generation of tech leaders to act; we must train and inspire them to implement sustainable solutions and carry the torch.

For more information, visit: www.belfercenter.org/TAPP

Helena Rong is an urbanist, researcher, and designer with interdisciplinary training. She is a Technology and Public Purpose (TAPP) Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and an Urban Planning PhD candidate at Columbia University. Her research lies in the intersection of digital technology, collective intelligence and urban planning and governance. Currently, she is investigating the potential of disruptive technologies such as blockchain to enable collective decision-making and engagement in urban governance and planning in the Web3 era. Rong received her Master of Science in Urbanism (SMArchS) degree from MIT and Bachelor of Architecture from Cornell University, where she graduated with the Charles Goodwin Sands Memorial Silver Award (1st Place Thesis Award).

Rong has led a number of research publications in peer-reviewed journals such as Buildings, European Transport Research Review and Landscape and Urban Planning among others. Her work has been featured on platforms such as ArchDaily, WallPaper magazine and Bustler, and exhibited internationally at Haus der Architektur Graz, Shenzhen Biennale 2019, solo exhibition in New York among others. Previously, Rong worked as a Research Associate at the MIT Real Estate Innovation Lab, where she led the “Value of Design” research pillar that studies the impacts of architectural design on commercial real estate asset pricing; and at the MIT Senseable City Lab, where she led the development of a model for travel optimization to museums in Amsterdam using autonomous waterborne vehicles. Rong is the founder of CIVIS Design and Advisory LLC, a design and research practice based in Boston and Shanghai that engages in multi-scalar and interdisciplinary architectural and urban projects.

Trust in democratic institutions has waned in recent years, stemming from insufficient transparency and representation in public decision-making processes, expanding social and wealth disparities, and growing apprehensions surrounding mis/disinformation fueled by the emergence of highly persuasive AI-generated content such as ChatGPT. Decentralized Web3 technologies such as blockchain emerged as instruments for creating an alternative “trustless” system that uses cryptography and decentralized consensus mechanisms to obviate the need for third party human intermediaries, but suffered significant setbacks due to massive frauds and speculations throughout the past decade of their evolution. Although it might appear counterintuitive to advocate for the potential benefits of these technologies in light of their evident failures, we assert that, before dismissing them, it is essential to differentiate the technological layer from the social layer in these instances and examine them with greater care and criticality. We argue that the recurrent failures of blockchain-based projects, as reported in the media and denounced by critics, are less indicative of the technology’s inherent weakness, and more a consequence of malicious actors exploiting the social layer within the system.

What is thus heavily lacking in the current Web3 landscape is the collaborative development and innovation in the social and institutional layer to build systems that genuinely enhance democracy and address the trust crisis society faces as a whole in a more sustainable way through leveraging the capabilities offered by decentralized technologies. As such, rather than perceiving these technologies as decentralized trust-replacing technologies, we consider them as “Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies” (DTTs). DTTs do not seek to replace trust, but instead serve to fortify trust through transparent and secure mechanisms combined with robust institutional designs.

In this report, we investigate a variety of case studies that showcase emerging efforts to employ DTTs in the physical realities and the built environment of our social institutions. These empirical examples offer valuable insights – both inspirational and cautionary lessons – into the practical applications of DTTs in transforming our society and lived environments. From this empirical analysis, our goal is to establish a set of guidelines and best practices for current and future endeavors in fostering innovation within this space, ultimately paving ways for more resilient and sustainable lived ecosystems that harness the power of DTTs.

1. Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies (DTTs) offer a technical infrastructure to provide a tamper-proof source of truth, but this does not automatically lead to trust.

2. DTTs hold the potential to innovate across a range of social institutions, including identification, voting and governance, titling and rights management, collective ownership, financial transactions, record keeping, civic participation, and regenerative economies.

3. DTTs can help enable wider participation and coordination at scale, but they should balance between undifferentiated mass involvement and particularized local control.

4. DTT applications can be driven by institutions, grassroots initiatives, or collaborations among stakeholders to achieve different goals.

5. DTTs hold the potential to help foster a shift from extractive to regenerative economies, ultimately providing sustainable economic benefits to local communities.

6. To enhance the trustworthiness of both technology and institutions, it is crucial to build systems not just for the community, but collaboratively with the community in participatory design processes.

7. Policymakers need to better understand both risks and benefits of DTTs to effectively integrate them into our existing systems.

All artwork generated by AI Through Midjourney

All artwork generated by AI Through Midjourney

In this report, we explore an array of use cases in which Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies employed widely in virtual domains (URL) have been intersected with the physical and material realities of our social institutions (IRL, or “in real life”), ranging from government-led experimentations in policy innovations, to decentralized grassroots efforts in collective ownership and governance of real world assets and public goods. Through this empirical analysis, we propose a set of recommendations and best practices to guide present and future initiatives in promoting innovation within this domain. Ultimately, we aim to pave the way for more resilient and sustainable living ecosystems that harness the potential of DTTs.

In Section 2, we examine the trust crisis faced by contemporary democratic institutions, provide an overview of Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies, discuss their major application areas for the social institutional building blocks of democracy – including identification systems, voting and governance systems, titling and rights management, collective ownership, financial transactions, public record keeping, civic engagement and participation, and regenerative economies – and highlight open questions that ask how we can think about these systems differently with DTTs. We further explore the pitfalls and promise of DTTs for transforming democratic governance.

In Section 3, we outline our research methods and present case studies in three subsections. We reflect on three key areas where DTTs can influence or transform democratic governance in social institutions; chiefly: 1) information transparency and security for trustworthy e-governance; 2) wider participation and coordination for multiple publics; and 3) economic benefits for local communities.

In Section 4, we discuss the overall key takeaways from our research and highlight future outlooks and potential research directions. Given the rapid expansion of the field, the cases surveyed in this report do not represent a comprehensive overview of all emerging innovations in DTTs. This report serves as an open invitation for technologists, policymakers, designers, and users to collaborate in finding ways to maximize the benefits of Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies, with the aim of elevating democratic governance and addressing the trust crisis in the Age of AI, while defining a value foundation for its development.

Trust is defined as the belief or confidence that one party (the “trustor”) has in the reliability, integrity, and ability of another (“the trustee”) to act in a manner that is consistent with one’s interests and expectations of a forecasted future.1 It involves a willingness to rely on another party to fulfill their promises, commitments, and obligations, even in situations that involve a necessary “leap of faith” that would expose one to uncertainties or risks. Trust can be built on confidence through repeated positive interactions and experiences with the other party (interaction-based trust), as well as on faith through evidence of shared value and transparency between two parties (institution-based trust).2 Meanwhile, trust can be eroded or broken through failure of the trustee to deliver expected promises, inconsistency, deception, power imbalance, and lack of communication in behavior or action.

Many Western democratic countries have recently observed a significant decline in both citizens’ trust in institutions and their levels of engagement. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer (a global survey measuring trust levels in 28 countries),3 trust in institutions such as governments, businesses, media, and NGOs has reached its lowest point in several decades. This is due to a number of reasons.

Internally, the overall lack of transparency in public decision-making, coupled with the ineffectiveness of current democratic systems for representation, hinders the establishment of meaningful connections between civil society and government institutions. In certain contexts, entrenched systemic inequalities undermine the trust individuals hold in institutions, resulting from a sense of exclusion, unfair treatment, historical trauma, and lack of accountability.

Externally, global crises such as Covid-19 and rapidly intensifying climate change exacerbate existing social and wealth inequalities by aggravating disparities in access to essential services, availability of resources to remain resilient, and

1 Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 438-458.

2 Graham Dietz (2011) Going back to the source: Why do people trust each other?, Journal of Trust Research, 1:2, 215-222; Niklas Luhmann, “Familiarity, Confidence, Trust: Problems and Alternatives,” in Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, ed. Diego Gambetta (New York: B. Blackwell, 1988); Anthony Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press, 1990).

3 The Edelman Trust Barometer. (2022). https://www.edelman.com/trust/2022-trust-barometer

opportunities for social and economic mobility. Consequently, vulnerable populations face increased challenges in overcoming these adverse effects, which ultimately leads to a further erosion of trust in institutions that are meant to be designed to safeguard the public interest.

More recently, disruptive digital technologies, while bringing immense benefits to society in terms of connectivity and democratization of information, have simultaneously introduced new challenges concerning trust. For example, although social media platforms developed by private tech companies have inarguably enabled a globally connected society, these platforms have also inadvertently facilitated the coordination and dissemination of mis/ disinformation by actors across spatial and temporal boundaries. As a result, the traditional role of physical geographical distances as moderating buffers in representation is effectively challenged, leading to amplified political polarization.

Now, the sudden unleash of generative artificial intelligence and synthetic media such as ChatGPT into the public realm5 introduces an unparalleled trust crisis that the current democratic system is ill-equipped to confront. At the same time, as the digital public realm is about to be inundated with emerging AI-related challenges

4 Edelman. (2022). 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer: The Cycle of Distrust. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2022-trustbarometer

https://www.theverge.com/2023/3/23/23653591/openai-chatgpt-plugins-launch-web-browsingthird-party

such as proliferation of deepfakes6 and intensified mis/disinformation, physical cities are simultaneously on the brink of facing social and economic complications such as substantial job losses expected from AI-enabled automation. As seen in global responses to other ongoing pressing issues such as racism, inequality, and climate change, cities will again serve as the hubs for innovation to lead and develop new tools and new models of democratic innovations to protect and advance the public good in this new age of trust crisis.

Despite the predominantly negative sentiments towards blockchain due to the catastrophic failures of several crypto projects in 2022, it is crucial to remember that the genesis of blockchain in Bitcoin was founded upon a vision to build a decentralized network based on “trustless trust” in response to the trust crisis triggered by the 2008 financial crisis.7 At the time, erosion of trust in traditional trusted institutions such as banks has given rise to the emergence and adoption of an alternative “trustless” system that uses cryptography and decentralized consensus mechanisms to eliminate the need for third party human intermediaries. As such, the raison d’etre of a blockchain system is that its operation does not require trusted human third parties (therefore it is “trustless”), marking what Bitcoin proponent Andreas Antonopoulos calls a “shift from trusting people to trusting math”8 (therefore a new type of “trust” in deterministic computation and code).

As legal scholars De Filippi, Mannan, and Reijers point out, however, such conviction that a blockchain-based system is “trust-less” or “trust-free” is highly misplaced.9 Blockchain does not replace trust; instead, it increases the confidence users have in a system which stems from the belief that the system is built on decentralization, tamper-proof mechanisms, transparency, and resistance

6 Atleson, M. March 20, 2023. “Chatbots, deepfakes, and voice clones: AI deception for sale.” Federal Trade Commission: Protecting America’s Consumers. https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/blog/2023/03/chatbots-deepfakes-voiceclones-ai-deception-sale

7 T.C. Earle, Trust, confidence, and the 2008 financial crisis, Risk Anal. 29 (6) (2009) 785–792.

8 A. Antonopoulos, Bitcoin Security Model: Trust by Computation. O’Reilly Radar, 2014. February 20. https://radar.oreilly. com/2014/02/bitcoin-securIty-model-trust-by-computation.html

9 De Filippi, P., Mannan, M., & Reijers, W. (2020). Blockchain as a confidence machine: The problem of trust & challenges of governance. Technology in Society, 62, 101284.

to censorship.10 What has been less scrutinized is that apart from the technical layer that the system is built upon, a blockchain-based system also involves a complex and less predictable social layer that involves an array of human actors – such as software developers, miners, validators, token holders, end-users, and regulators –who collectively shape and contribute to the functioning of the entire ecosystem. In other words, trust is not absent, but is simply diffused and delegated to a much more sophisticated and unknown assemblage of social actors that are involved in building and interacting with the technology, rendering the entire system much more than a technical system, but a sociotechnical one.

Bitcoin, with its straightforward and single function as a decentralized digital currency enabling peer-to-peer transactions, can easily showcase the technical capabilities and robustness of a secure and decentralized system; and indeed, the technical blockchain infrastructure of Bitcoin has never been hacked or compromised since its launch in 2008.11 However, when the technology attempts to more closely integrate and interact with existing systems in much more complex use cases, blockchain-based systems often falter due to the inadequacy of our current models in addressing vulnerabilities in the social layer, such as poor governance, inadequate security practices, insider attacks, centralization risks, human error, social engineering attacks, and misaligned incentives. Thus, the frequent failures of blockchain-based projects reported in media and denounced by critics12 are less a reflection of the technology’s fragility, and more a result of malicious actors interacting with the system who exploit the social layer.

What is heavily lacking in the current Web313 landscape is the collaborative development and innovation in the social and institutional layer to build systems that genuinely enhance democracy and address the trust crisis society faces as a whole in a more sustainable way through productively leveraging the capabilities offered by decentralized technologies. As such, rather than perceiving these technologies as decentralized trust-replacing technologies, we consider them as “Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies14” (DTTs), ones that do not seek to replace trust – a fundamental aspect of human nature – but serve to fortify trust through transparent and secure mechanisms combined with robust institutional designs.

10 Ibid.

11 Chainanalysis. (2021). The Chainanalysis 2021 Crypto Crime Report. https://go.chainalysis.com/2021-Crypto-Crime-Report.html

12 White, Molly. (2023). Web3 is Going Just Great. https://web3isgoinggreat.com/

13

14

1 Distributed ledger technology (DLTs)

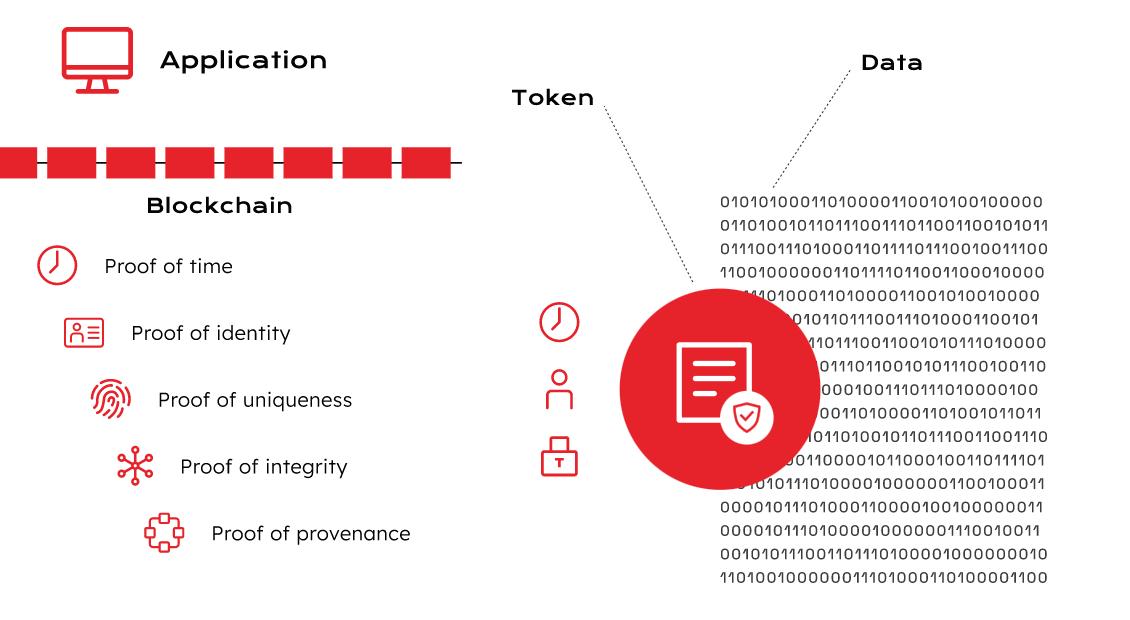

DLT is a decentralized database technology that allows multiple participants to share and synchronize data without intermediaries. This creates a distributed, immutable ledger of transactions, shareable and verifiable securely among multiple parties. Blockchain, a DLT example, uses cryptographic techniques to secure and validate transactions. Each block in the chain contains a set of transactions or other data that is timestamped and validated by a network of computers called nodes using a consensus algorithm such as Proof-of-Work (PoW) or Proof-of-Stake (PoS). When a transaction is made, it is broadcast to the nodes on the network, which validate the transaction and add it to a block. The block is then added to the existing chain of blocks, forming a permanent and unalterable record of the transaction.

2 Cryptocurrencies

A cryptocurrency is a digital currency that uses cryptography for security and runs on a blockchain. Created through processes like mining (in PoW) or staking (PoS), cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin or Ethereum operate independently of a central bank, with values determined by market forces.

3 Stablecoins A stablecoin is a type of cryptocurrency designed to maintain a stable value by pegging it to a reserve of assets, such as fiat currency like the US dollar or a commodity like gold. Stablecoins aim to combine the benefits of cryptocurrencies, such as decentralization, transparency, and fast transactions, with the price stability of traditional currencies or other stable assets. This makes them more suitable for daily transactions than other cryptocurrencies that fluctuate in price based on the market. Examples of popular stablecoins pegged by the US dollar include Tether (USDT), USD Coin (USDC).

4 Decentralized finance (DeFi)

5 Decentralized Apps (dApp)

6 Decentralized autonomous organization (DAO)

DeFi is a financial ecosystem built on blockchain technology and smart contracts that enables users to access financial services such as lending, trading and borrowing peer-to-peer without intermediaries like banks.

Unlike traditional apps, which are centralized and run on servers owned by a single entity, dApps operate on a distributed network of computers that are owned and operated by many different people.

A DAO is a digital-native organization that operates on a blockchain. It utilizes smart contracts to manage and govern shared resources, allowing token holders to carry out decentralized decision-making and collaboration.

7 Fungible token Fungible tokens15 are digital assets that are interchangeable with each other and have identical properties and values, such as aforementioned cryptocurrencies and stablecoins.

8 Non-fungible token (NFT)

9 Non-custodial wallet

An NFT is a type of digital asset that is unique and cannot be replaced or exchanged on a one-to-one basis. An NFT is usually used to represent ownership or proof of authenticity of a specific asset that has unique properties, such as digital art, music, and more recently, digital representation of physical goods and rights such as voting rights and title deeds. In DAOs, governance rights can be represented using either fungible and non-fungible tokens, depending on how they are designed and implemented.

A noncustodial wallet is a crypto wallet that allows users to maintain full control over their digital assets without relying on a third-party custodian. In other words, users possess full ownership of their private keys, which are necessary to access and control their cryptocurrencies. To manage shared resources of an organization, a multisig (or multisignature) wallet is used to enhance the security of funds by requiring multiple signatures or approvals before a transaction can be executed.

15 A token is defined by the SEC as “a digital representation of values or rights,” that has an unmodifiable transaction history on the blockchain and can be exchanged between persons or entities without an intermediary. See: Peirce, Hester M. April 13, 2021. “Token Safe Harbor Proposal 2.0.” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. https://www.sec.gov/news/publicstatement/peirce-statement-token-safe-harbor-proposal-2.0

Before exploring the present challenges and potential future benefits of Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies, we first unpack and de-jargon several key components within this suite of technologies. Additionally, we identify application areas or social institutions where they could have the most significant impact related to democratic governance, followed by some guiding design and design research questions related to their implications.Table 1. The Technical Building Blocks of Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies

10 Smart contract Smart contracts are self-executing computer programs stored and replicated on a blockchain network that typically automatically execute the terms of an agreement between two or more parties. They are designed to ensure that contractual obligations are carried out automatically without the need for intermediaries.

11 Cross-chain bridge

A cross-chain bridge is a technical architecture that enables the transfer of digital assets or tokens between different blockchain networks by creating a link between them through smart contracts. It facilitates interoperability by functioning as an intermediary that enables two or more blockchains to trade-off their efficiencies, decentralization, and security.

12 Zero-knowledge proof (ZKProof)

Zero-knowledge proof is a type of cryptographic protocol that allows one party (the prover) to prove to another party (the verifier) that a certain statement is true without revealing any additional information beyond the statement being proved for privacy protection purposes.

Social Institutions

1 Identification systems

Description of impact area and potential transformation with DTTs

The function of the state is to count people. Identification systems have existed since the Babylonian Empire during 3800 BC.16 The modern identification systems emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the development of photography and fingerprinting techniques. Historically, identification has been used to categorize people based on social statuses (e.g. single, married) and has sometimes been employed as a tool for exclusion by the state by delineating boundaries between the accepted and the “other” (e.g. citizen, foreigner, illegal immigrant). The institution of the passport allowed the state to “monopolize the legitimate means of movement…and individual existence.”17 Today, the proliferation of mis/disinformation in the digital sphere introduces new challenges in identifying credible sources for digital participation, which requires not only distinguishing between human from human, but also human from machine (bots). In a decentralized environment where verification can be conducted by a range of stakeholders rather than a centralized entity such as the government, one proposed area of innovation enabled by DTTs is self-sovereign identities, where individuals control their digital IDs and information can be verified through a decentralized network of nodes.

Open design questions:

How might we design a decentralized digital ID system that promote inclusion by incorporating an inclusive and decolonial framework, such as the UN’s “protect, respect, remedy”18 approach?

How might we design an identification system that balances security and privacy protection with the need to verify the identification of a digital participant in order to prevent malicious actors from spreading false information?

16 Veriff. May 10, 2022. The history of ID. https://www.veriff.com/blog/the-history-of-id

17 Caplan, J., Torpey, J., & Torpey, J. C. (Eds.). (2001). Documenting individual identity: The development of state practices in the modern world. Princeton University Press. pp. 256-257.

18 The “protect, respect, remedy” framework is proposed by the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights that refers to the responsibilities of states and businesses in ensuring that human rights are protected in the context of business activities.

2 Voting and governance systems

Voting is a vital aspect of maintaining a healthy democracy, as it enables citizens of a state or members of an organization to partake in the decision-making process that impacts their lives and communities. Intrinsically linked to the social institution of identification, voting eligibility relies on the verification of one’s membership within a particular organization or group. As individuals possess multiple identity categories and their affiliations become increasingly pluralistic, the institution of voting must adapt to accommodate variations among voters within the same category and support diverse plural identities. A robust digital infrastructure presents opportunities to explore and implement more sophisticated forms of governance, such as liquid democracy (which combines the benefits of both direct and representative democracy), and quadratic voting (which weighs in a voter’s degree of preference).

Open design questions: How can we think about these systems differently?

How might we design governance systems that accommodate variations among voters within the same category?

How might decentralized systems create effective incentive structures to encourage honest participation, discourage malicious behavior, and reward those who contribute to the system’s security and stability?

How might different decentralized platforms and systems work together to enable seamless voting and governance processes across various jurisdictions and organizations?

3 Titling and rights management

Titling and rights management systems are used to maintain records of ownership and rights of assets such as real estate titles and intellectual property rights, and are usually issued by a centralized authority such as a government agency or a private company. One of the main problems with the current system is the potential for errors and fraud, as the centralized authority may be susceptible to corruption or technical errors. Additionally, the process of transferring ownership or usage rights can be slow, expensive, and require the involvement of multiple parties. DTTs such as DLTs and NFTs have the potential to help reduce fraud and errors, as well as more efficiently streamlining the process of transferring ownership or usage rights.

4 Collective ownership Existing models for co-ownership of assets, such as companies, real estate, or other divisible and shared assets, face significant barriers to entry due to challenges in legal structures, governance and decision-making, funding and financing, management and maintenance, and cultural norms that prioritize individualism. Recently, DTT innovations such as DAOs, smart contracts, and token engineering present early signs of potential to overcome these barriers and enable collective ownership at scale. The use of digital voting tools like Snapshot has enabled DAOs to experiment with collective ownership and management of shared assets on an unprecedented scale. However, many current experiments with DAOs have yet to establish effective governance models that present a strong use case for these organizations. DAOs face the challenge of balancing efficient leadership to prevent the “tragedy of the commons” while maintaining sufficient decentralization.

5 Financial transactions Current financial transactions are characterized by the need for intermediaries such as banks and financial institutions to process and verify transactions. This can lead to delays, high fees, and a lack of transparency in the process. In many cases, these intermediaries can sell or share user data with third-party companies for marketing and advertising purposes, without the knowledge or consent of the users. Additionally, the centralized nature of these intermediaries means that they have the power to control or censor transactions, which can limit access to financial services for certain individuals or groups. Some of the key appeals of a blockchain-based fund transfer system include ease of cross-border transactions, lower fees, instant settlement, protection of user privacy, and prevention of sale or misuse of user data by intermediaries.

How might we ensure that blockchain-based titling and rights management systems are equitable and accessible to all users, regardless of their socioeconomic status or geographic location?

How might we design these new systems that ensure recognition and acceptance by existing systems and institutions, in order to protect the rights and interests of owners?

How might we design systems that do not conflate ownership with voting rights of collectively shared (public) assets to ensure equity?

In governing shared assets, how can voting mechanisms be designed to prevent voter apathy, reduce the influence of large token holders, and promote informed decision-making?

How might we establish clear regulatory guidelines and standards for blockchain-based transactions to ensure compliance with AML/ KYC regulations, taxation laws, and consumer protection laws?

6 Public recordkeeping

The institution of public record-keeping involves the use of centralized databases managed by government agencies or other organizations. While many such agencies have adopted digital records management systems for storing and accessing public records, paper records continue to exist in numerous instances. From a security standpoint, centralized record systems are susceptible to hacking, fraud, tampering, and deletion. DTTs such as blockchains provide a decentralized and more transparent alternative for keeping public records. Furthermore, DTT systems offer potential tools that enable more diverse and decentralized methods of record verification, shifting the legitimacy of records from being solely state-issued to incorporating more dynamic and pluralistic approaches for verifying identification and records.

7 Civic engagement and participation

Civic participation currently faces multiple challenges, including uneven access for various social and demographic groups; lack of motivation; distrust in the process due to perceived ineffectiveness; unengaging designs of e-participation platforms; and disconnect between participation processes and actual decision outcomes. DTTs offer tools to improve transparency, traceability of community input, and more effectively incentivize participation through rewards. However, open questions remain, such as addressing inclusivity (tackling the digital divide), educating the public about the technology to increase adoption, and gradually building trust within communities.

8 Regenerative Financial Systems

Relatively a newer concept that has just emerged in recent years, regenerative finance (ReFi) describes a financial system that seeks to support ecological regeneration, social justice, and economic resilience through aligning financial investment incentives with values of sustainability, equity, and justice. An emerging direction is tokenizing and monetizing natural capital to protect natural assets and onboarding Global South players to participate in the ecological credit markets.

Open design questions: How can we think about these systems differently?

How might we design systems that allow for more pluralistic and dynamic ways of verifying records, without compromising accuracy and authenticity?

How might a balance be achieved between transparency and privacy, given that blockchain is inherently transparent and public?

What type of consensus mechanism should be employed in a decentralized record-keeping system?

How might we convey abstract technical concepts of transparency and immutability to end-users through accessible language and user-centric design interfaces?

How might we design systems that effectively complete the feedback loop, connecting inputs to outcomes, potentially by integrating other analytical technologies like natural language processing?

How might we design incentives that align the interests of various global players, encouraging them to collectively contribute to the efforts of regenerative finance?

What alternative indicators and metrics, beyond conventional financial returns, can be used to assess the success of regenerative finance initiatives in terms of social, environmental, and cultural impacts?

The evolution of the Web3 and crypto space has undergone substantial fluctuations throughout the past decade. This dynamic era has been fraught with pronounced hype cycles, theatrical failures, and restless controversies. Most recently, the dramatic collapses of Three Arrow Capital,19 Terra/Luna,20 and FTX,21 occurring one after the other, have led skeptics and critics to affirm their belief that the crypto industry lacks redeeming qualities and that its underlying technology, blockchain, is essentially useless.22

It is certainly difficult to refute such allegations when all the evidence making the headlines so far point to massive frauds and scams. However, we would like to stress again the need to distinguish the technological layer from the social layer of these instances of failure and scrutinize them with more care and criticality. One stark irony in all of these debacles is that their collapse was not due to the technical defect in the decentralized technology per se; but rather due to the lack of transparency in the oversight, decision-making structures, and accounting systems within highly centralized governance systems. This juxtaposition highlights a desperate urgency in innovating in the social layer of these technological assemblages to better build trust in governance and democratic decision-making procedures. And we argue that the same tools that have contributed to the successful construction of decentralized technical networks also possess the potential to help create decentralized trust networks that can facilitate better decision-making procedures, provided that they are combined with thoughtful design principles, well-informed ethical guidelines, and deliberate governance frameworks that are capable of addressing both existing and emerging trust-related challenges.

A similar stance is taken by a recent report from the Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University entitled Ethics of Decentralized Social Technologies:

19 Dugan, K. June 17, 2022. “Another Big Crypto Player Just Blew Up.” New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/ intelligencer/2022/06/crypto-hedge-fund-three-arrows-capital-just-blew-up.html

20 Sandor, K., and Genç, E. December 22, 2022. “The Fall of Terra: A Timeline of the Meteoric Rise and Crash of UST and LUNA.” CoinDesk. https://www.coindesk.com/learn/the-fall-of-terra-a-timeline-of-the-meteoric-rise-and-crash-of-ustand-luna

21 Napolitano, E., and Cheung, B. November 18, 2022. “The FTX collapse, explained.” NBC News. https://www.nbcnews. com/tech/crypto/sam-bankman-fried-crypto-ftx-collapse-explained-rcna57582

22 Schneier, B. June 24, 2022. “On the Dangers of Cryptocurrencies and the Uselessness of Blockchain.” https://www. schneier.com/blog/archives/2022/06/on-the-dangers-of-cryptocurrencies-and-the-uselessness-of-blockchain.html

Lessons from Web3, the Fediverse, and Beyond. In the report, the authors identify the current development of these decentralized technologies as a “constitutional moment,“23 referencing legal theorist Bruce Ackerman.24 This refers to a historical moment in which introduction of new technologies trigger “transformations in: (1) political institutions, (2) the structure of civil society, (3) economic organization, (4) common understandings of political institutions/ civil society/economic organization, and/or (5) the apparatus of, and social relationships embedded within, the state.”25 The authors contend that this specific set of technologies may profoundly impact society due to their capacity to fundamentally alter social institutions and democratic structures. The outcomes could range from dystopian to desirable, depending on society’s ability to collectively and democratically manage these novel mechanisms. Consequently, the authors emphasize the pressing need of creating guiding values and guardrails to promote responsible technological advancement that can ultimately improve human flourishing.

Aligning with this perspective, we posit that Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies hold the potential to improve democratic governance and address the trust crisis in the Age of AI if we can establish a well-considered value foundation for its development. When considered in isolation, it is always difficult to answer the question, “What unique value-add do blockchain systems bring to the table that traditional Web2 technologies cannot achieve?” However, when considered more holistically, DTTs, working in combination with social institutional systems of identification, voting and governance, ownership, engagement, and more, can potentially restructure the ways in which we organize society and distribute resources in more equitable and dynamic ways. While simple use cases such as Bitcoin have demonstrated the technical robustness of a truly decentralized network, we are still in the very infant stages of exploring the integration of this technology stack with more sophisticated use cases that will be embedded in our complex social systems.

25 Ibid. pp. 6.

Far from being value-neutral, technologies can serve both domineering and liberating purposes depending on the values that are encoded into its conceptualization, design, implementation, use and management. Mass adoption of technologies such as blockchains without ethical and institutional frameworks could produce new forms of oligarchies and deepen societal polarizations,26 while well-guided approaches of using DTTs might have transformative potential to aid the exploration of innovative governance mechanisms and novel approaches to integrating democratic governance within decision-making processes.27 As such, the question of using Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies as our apparatus to build better democracies amid an unparalleled trust crisis is less about debating “Should we or should we not use this technology?” Instead, it is a proactive “How might we?” question that boldly seeks to innovate in human-centric policy designs, social institutions, and ethical frameworks to establish a system that is better suited for supporting democratic governance and trust-building.

In the subsequent section, we delve into a variety of case studies that showcase emerging efforts to employ DTTs in the physical realities and the built environment. These empirical examples offer valuable insights – both inspirational and cautionary lessons – into the practical applications of DTTs in transforming our society and lived environments. From this empirical analysis, our goal is to establish a set of guidelines and best practices for current and future endeavors in fostering innovation within this space, ultimately paving ways for more resilient and sustainable lived ecosystems that harness the power of DTTs.

3. Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies for Public Good: Learning From Recent Experiments in Decentralized Governance and Social Innovations

In this study, we employ a mixed-methods approach to examine 16 selected projects/initiatives (Table 4). For each project, we utilize a combination of gray literature review, semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, and digital ethnography of online activities. Our data collection process for all three methods is guided by an evaluation framework that seeks to understand both the intentions and the outcomes of the projects. The details of which are provided in Appendix A.

For each project, relevant textual data such as policy reports, white papers, references to municipal, regional, or national policy frameworks and legislation documents released by the state were collected for analysis. We have limited sources to official releases that have a direct impact on the implementation of the selected projects. Government sources encompass websites of the city and affiliated organizations. Non-government sources comprise official whitepapers released by the project team, as well as official websites and Twitter accounts associated with the projects.

We have conducted a total of 20 interviews with relevant stakeholders associated with the chosen projects. The majority of interviewees were members of the project’s founding team. In some instances, we also interviewed government stakeholders and key participants, such as DAO members and citizens, who participated in the projects. All interviews were conducted in English on video conferencing platforms such as Zoom and Google Meet. Each interview lasted for around 60 minutes. All interview transcriptions were qualitatively analyzed to help derive insights. Through both cold contact and personal connections, we were able to access at least one stakeholder for interviews from 13 out of the 15 selected projects. Due to time and resource constraints, the interview sample size for each case is small. We recognize this limitation and aim to offer a basis that can act as a launching pad for future research.

For projects with active online communities, such as CityDAO, CityCoins and Unit Network, we conducted digital ethnography in publicly accessible virtual spaces that do not require payment or exclusive registration for entry, including platforms like Discourse, Telegram, Twitter, and Snapshot. Following Pink et al. (2016), digital ethnography involves applying participant observation in the virtual world to gain insights on embodied social practices in the intertwined and overlapping digital and physical worlds.28 For these projects, we collected data such as announcements, comments, images, videos, and memes in discussion threads left by participants as digital traces for analysis. We focused on key debates and discussions among users, levels and patterns of member engagement, as well as normative practices, to complement the insights gained from stakeholder interviews and gray literature reviews. Data collection primarily took place between September 2022 to February 2023.

We have intentionally sourced diverse projects from around the world, varying in scale, geography, stage of implementation, and application, to illustrate the broad array of use cases in which DTTs (URL) have been intersected with the physical and material realities of society (IRL or “in real life”), varying from top-down institution-led endeavors, to bottom-up grassroots initiatives. As shown in Table 3, the selected projects encompass the eight social institution and use case domains we have identified in Section 2, under Table 2: 8 Key Application Areas of Decentralized Trust-Building Technologies for the Fundamental Building Blocks of Democracy within Social Institutions. Many of these projects are still in their infancy; however, the preliminary empirical evidence – both inspirational and cautionary – provides valuable insights that allow us to analyze their effects and outcomes and to extract lessons to guide current and future projects.

While we have selected the projects based on social institutional applications, we organize our findings in the subsequent subsections according to three overarching impact areas that have emerged during our qualitative analytical

process, namely: (1) information transparency and security for trustworthy e-governance; (2) wider participation and coordination for multiple publics; and (3) strengthening local communities.29

In the first set of cases, we examine projects that aim to harness DTTs to enhance transparency and accountability of government institutions across three spatial scales. We primarily present and discuss lessons from the nationwide digital infrastructure of e-Estonia, Reno’s city-wide pilot in public record keeping, and a community-scale experiment in civic participation in urban planning in Berlin.

In the second subsection, we delve into the potential of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) for democratizing ownership and governance of real-world assets, using CityDAO as an empirical example. Lastly, in the third subsection, we investigate initiatives that foster local resilience through digital local community currencies (or city-specific tokens), drawing insights from projects such as CityCoins, city3, Ibiza Token, and Kolektivo. These early empirical examples together reveal how DTTs can play a role in fostering trust and facilitating more resilient and sustainable democratic governance. At the same time, they underscore the outstanding challenges that must be tackled in order to fully realize their potential. (Note: Additional information on cases not included in the subsequent three subsections can be found in Appendix B).

1 Identification systems

2 Voting and governance systems

4

5

6 (Public)

e-Estonia

CityDAO, RenoDAO, Unit Network, Gitcoin Boulder Downtown Stimulus Program

CityDAO, RenoDAO, EarthFund

CityCoins, city3, Ibiza Token, Berkeley Microbond

Reno’s Biggest Little Blockchain, e-Estonia

7 Civic engagement and participation BBBlockchain, Swampscott Community in_PUT, Gitcoin Boulder Downtown Stimulus Program 8

29 Note: The content in these sections has been adapted from three distinct case study essays, each independently published: Rong, Helena, Mao, Zeslene. 2023 (upcoming publication). “Deep-Dive Into CityDAO: An Experiment in Collective Land Ownership and Decentralized Governance.“ Belfer Center.

Rong, Helena, Peng, Er Li. 2023 (upcoming publication). “Connected Digital Society: Paving Ways for Country-Scale Digital Interoperability in Estonia.” Belfer Center.

Rong, Helena, Dam, David. 2023 (upcoming publication). “From Community Currency to Crypto City Tokens: Potentials, Shortfalls, and Future Outlooks of New Old Ideas.” Belfer Center.

e-Estonia is a government initiative to facilitate Estonian citizen interactions with the state through the use of electronic solutions and digital public services. e-Estonia has been testing and implementing blockchain for data security since a devastating cybersecurity attack in 2007. As of 2019, 99% of public services in Estonia are available to citizens as e-services. Virtually all state-related operations – except marriage, divorce, and real estate transactions – can be carried out digitally.

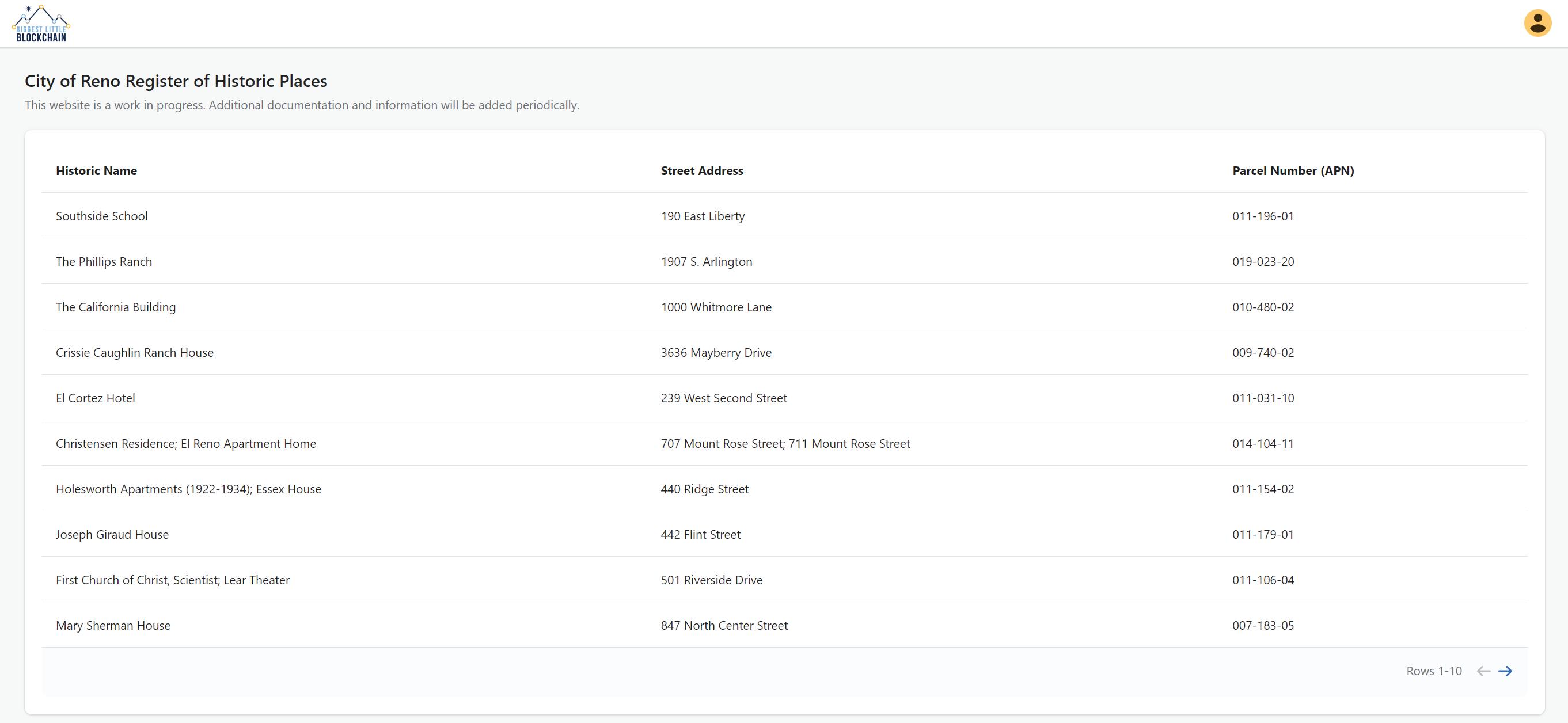

Reno’s Biggest Little Blockchain is a record-keeping blockchain for keeping the records pertaining to historic properties in the City of Reno, Nevada. The blockchain was built by a private company known as BlockApps, which is a service provider of private, permissioned blockchains. Only those with the necessary permissions are able to write to the blockchain, and information uploaded to the blockchain is publicly accessible through a website interface.30

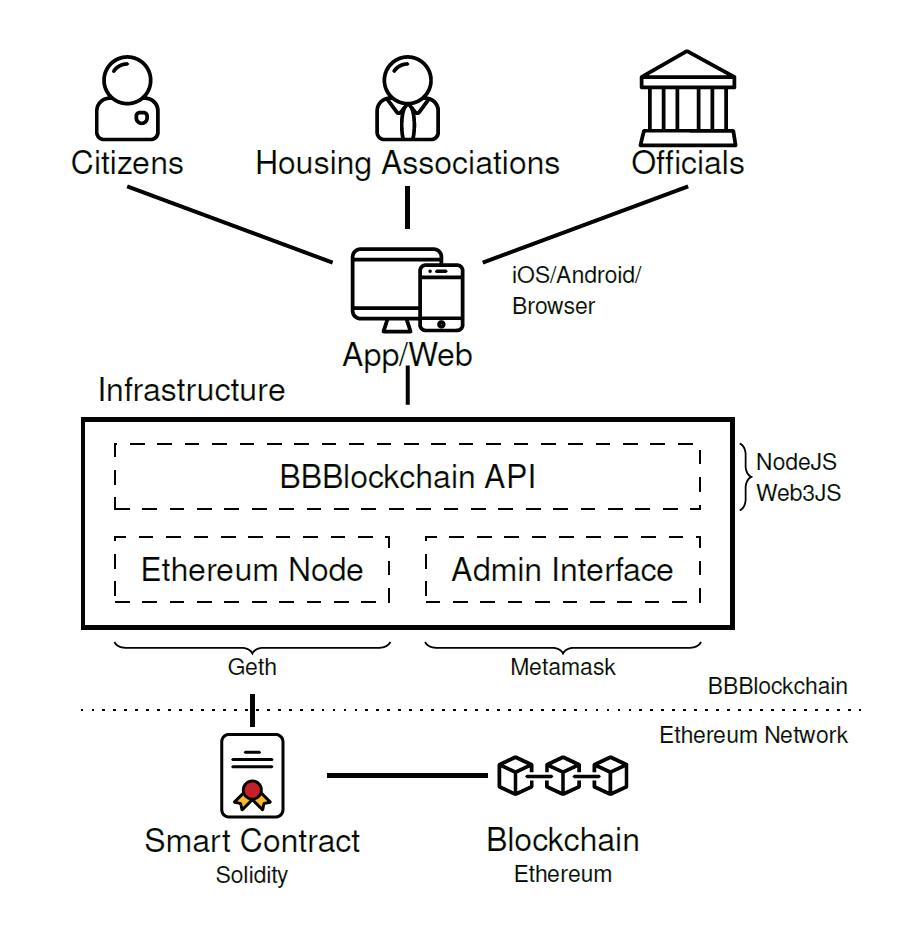

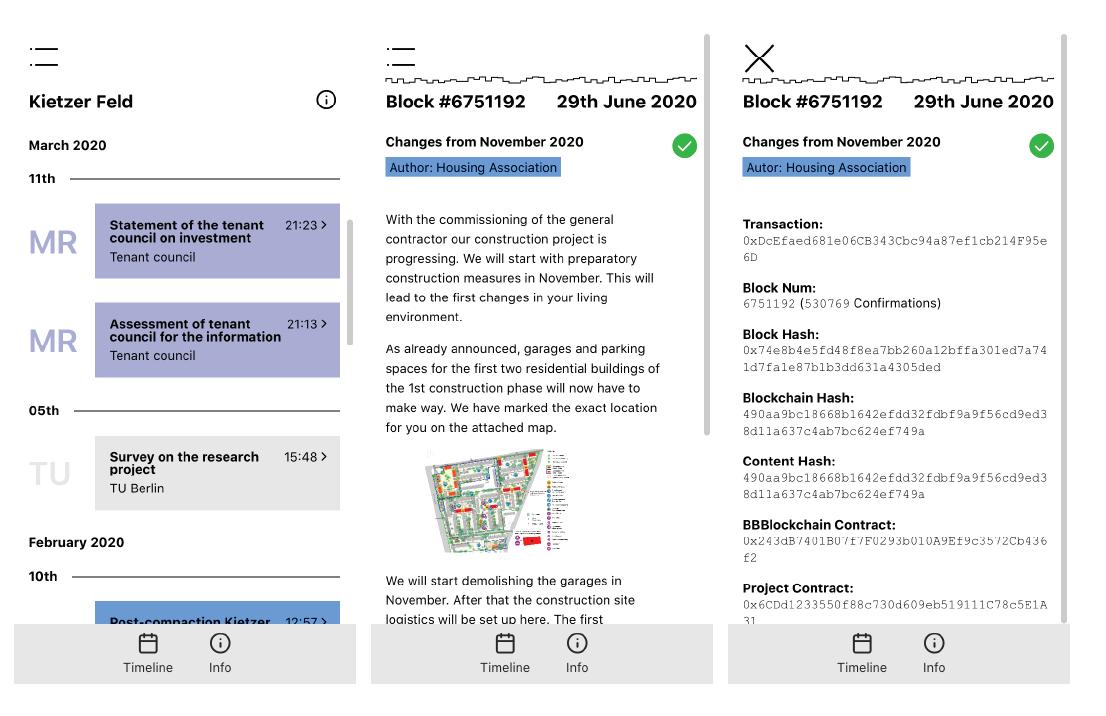

BBBlockchain is a blockchain-based participation platform to investigate how blockchain technology can improve participatory urban planning and seeing how a platform that allows for the management of documents, voting, and publication of proposals and feedback can enhance citizen participation and build a more inclusive process for co-creation.

BBBlockchain is an Einstein Center Digital Future research project supported by Berlin‘s six municipal housing associations.

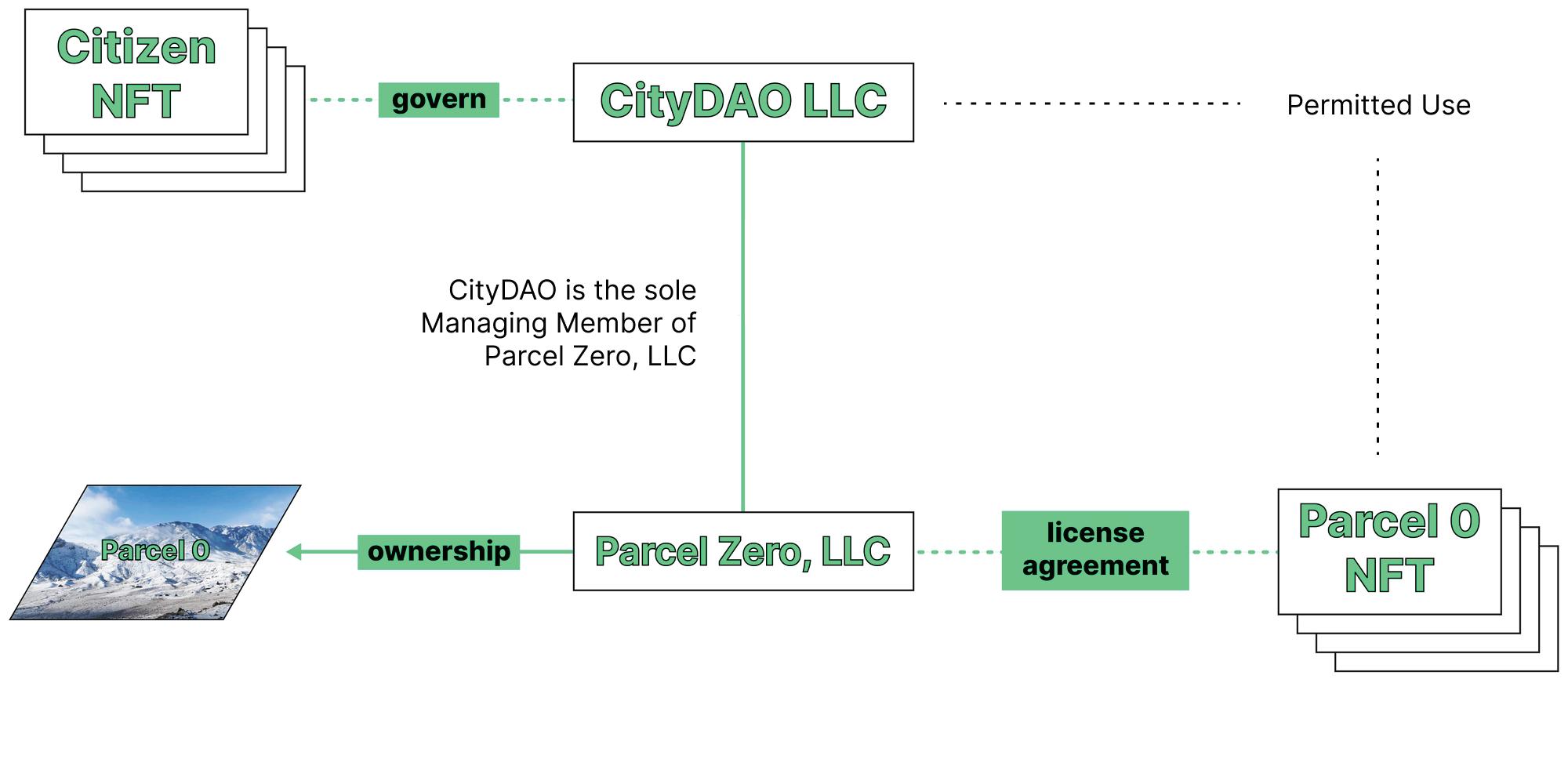

CityDAO is a decentralized autonomous organization registered in Wyoming, USA, whose mission is to build an on-chain, community-governed, crypto city of the future. Members possessing Citizen NFTs have rights to vote on governance matters such as the purchase and use of property.

Kolektivo is a framework to enable the creation of regenerative economies in communities. Using a geospatial smart contract standard, Kolektivo allows communities to register ecological assets on Ethereum as NFTs, establishing a basis for a nature-backed currency. Kolektivo seeks to launch the first Kolektivo Economy in Curaçao in 2023.

EarthFund is a DAO-as-a-Service company that allows anyone to easily establish a DAO through a single platform. The DAO that is launched would be listed on the Earth Fund website. At present, there are three sub-DAOs on EarthFund, being Never Alone (a DAO with a mission to find and fund mental health improvement projects), Female Empowerment DAO (seeking to empower women of color that have faced abuse and trauma) and Carbon Commons (for carbon-removal projects).

Single.Earth is a GreenTech company that seeks to develop a virtual ecosystem for the preservation of nature. It partners with landowners and organizations committed to preserving nature. Landowners join the Single.Earth platform, committing to use their land in an environmentally friendly way, receiving financial rewards in the form of cryptocurrency (i.e. the MERIT token).

EthicHub is a social enterprise built on the blockchain that facilitates the provision of microloans from investors to small farmers in Latin America with financing needs. Lenders provide capital to farmers through stablecoins and a DeFi architecture for collateral secures the lending to minimize the risk of defaults.

RenoDAO was a project announced by the City of Reno to develop a decentralized autonomous organization for the citizens of Reno. The project envisaged the issuance of two types of tokens - a governance token for voting purposes and a stablecoin which would be used for transactions. This project is not currently active.

Mike Gault(CEO

and Founder of Guardtime)Two Estonian citizens

Nic Ciccone (Legislative Relations Program Manager, City Manager’s Office); Jeffry Powell (Vice President of Sales, BlockApps)

N/A

Scott Fitsimonies (Founder of CityDAO); Favian Valencia (member of CityDAO’s council)

Luuk Weber (Pioneer of Kolektivo Labs)

Adam Boalt (Founding Investor and Advisor, EarthFund)

Tarmo Vikri (Head of Communications, Single.Earth)

N/A

Teddy Clapp (Smart Contract Engineer, RenoDAO)

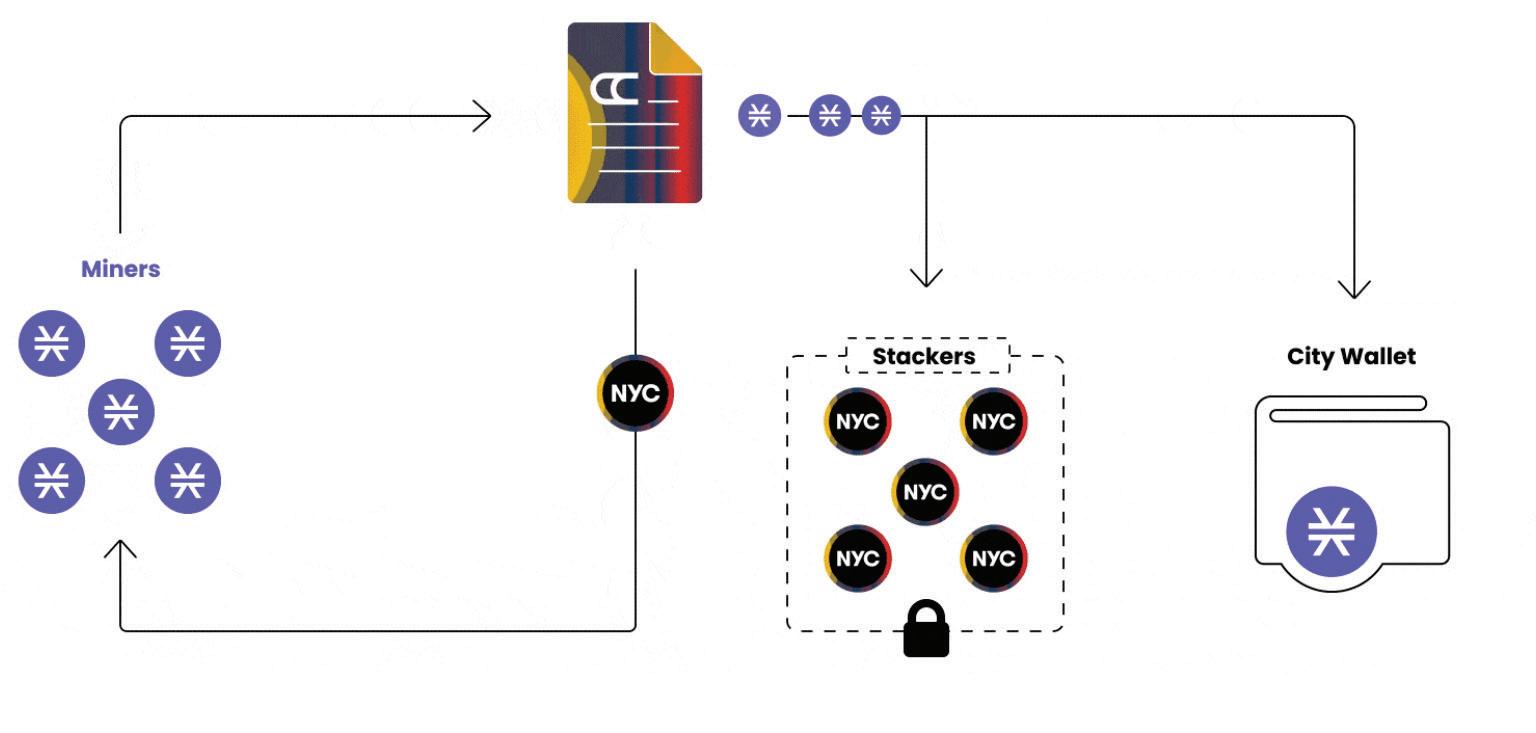

CityCoins combines financial incentives to hold and mine tokens with revenue generation for cities. Whenever a user obtains a native token (STX) on the Stacks blockchain, 30% of the STX tokens goes to the participating city’s wallet and the remaining 70% is sent to holders of CityCoins who choose to “stack” their tokens.

Unit Network provides a platform based on blockchain technology so people, businesses, or even cities can build their own token economies. Anyone can create their own token to share the value captured by their brand.

Michael Bloomberg (Visiting researcher at Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute)

Michael Healy (Co-Founder of Unit Network);

Zachary Kerschberg (Co-Founder of Unit Network);

Ann Boothello (Co-Director Unit Network)

$OAK is a proposed digital community currency pegged to the dollar, and aims to develop and govern a pool of shared community assets in Oakland, California. Through their merchants payments network, community governance system, and community ownership, the project hopes to generate pathways toward self-sufficiency.

Darrell Jones III (Co-Founder and CEO of city3)

Ibiza Token is a utility token that grants access to exclusive marketplaces for local artists’ NFTs, discounts at local shops, and tickets to local events. The aim is to better generate and circulate wealth within the island.

Remo Frisina (Co-Founder and CEO of Ibiza Token);

Marco Frisina (Co-Founder and CMO of Ibiza Token)

Gitcoin Boulder Downtown Stimulus project’s purpose is to raise capital for downtown Boulder’s downtown local businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic using quadratic fundraising.

Berkeley is slated to become one of the first cities in America to incorporate blockchain technology into its municipal bond market through a government-backed initial coin offering. Berkeley City Council voted unanimously in December 2021 to authorize the city manager to contract with a firm to provide professional services with a microbond financing program. They hope to make the municipal bond issuance process faster, cheaper, more transparent and more accessible to community members.

Scott Moore (Co-Founder of Gitcoin)

Ben Barlett (Berkeley City Council member)

Trust is a complex and multifaceted social phenomenon with varying interpretations on its source and substance. Within the trust literature in the social sciences, researchers have explored and identified multiple types of and sources of trust. According to management scholar Graham Dietz, various types and sources of trust follow a sequential pattern during different stages of their development.31

First, there is a psychological evaluation of a party’s trustworthiness that is based on the trustee’s ability, benevolence, and integrity.32 Then, when a trustor perceives the trustee as trustworthy, they are more prepared to be vulnerable, leading to a potential risk-taking act.33 The outcome of the interaction leads to reassessment and update of that trustworthiness, and such a cycle continues and repeats. Overtime, trust develops as a result of both confidence and faith. 34 Trust based on confidence stems from repeated positive experiences and interactions (i.e., trust in using an ATM machine) which leads to an attitude of reassurance and a sense of predictability and certainty. On the other hand, trust based on faith derives from an alignment of values that are reliant on non-verifiable factors (i.e., faith in a city government),35 such as shared experiences and a sense of belonging with other members of the community or institution.

At its inception, blockchain seeks to establish a new architecture of trust by enforcing deterministic outcomes through software code to effectively remove the need to trust untrustworthy intermediaries, both at the level of infrastructure and application.36 Blockchain enthusiasts contend that various technology design implementations such as decentralization, open source technology, radical transparency, and abstraction of problems and solutions to mathematics offer the

31 Dietz, Graham. (2011) Going back to the source: Why do people trust each other?, Journal of Trust Research, 1:2, 215-222.

32 Schoorman, F.D., Mayer, R.C., & Davis, J.H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), pp. 344354.

33 Dietz, Graham. (2011) Going back to the source: Why do people trust each other?, Journal of Trust Research, 1:2, 215-222.

34 Seligman AB (2000) The Problem of Trust. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

35 Gordon, Eric, and Tomás Guarna. (2022). Solving for Trust: Innovations in Smart Urban Governance.

36 Bodó, B. (2021). Mediated trust: A theoretical framework to address the trustworthiness of technological trust mediators. New Media & Society, 23(9), 2668-2690.

technological tools to tackle systemic trust problems in trust mediation.37 As such, through the removal of trust in intermediaries through code, blockchain is widely understood to be a type of trust that is “trustless.”

As highlighted previously, however, these technological trust guarantees are inadequate prerequisites for establishing trustworthiness. While hard-coding rules into the system introduces higher predictability of outcomes and thereby produces confidence-based trust in the technology as opposed to trust in a centralized human intermediary, trust in social institutions is not replaced but rather is diffused into a wider and more intricate network of actors that are involved in the creation, development, and use of the technology stack.38 This can be further influenced by local contexts, norms, institutions, regulations, and customs,39 as well as perception of the technology.

Within the realm of e-governance in the public sector, governments are increasingly becoming interested in exploring the integration of blockchain and other DTTs into a myriad of applications to increase institutional accountability and service delivery efficiency, such as record keeping, titling and rights management, and civic engagement and participation. However, very few institution-led cases to date are built on public blockchains, where a high degree of decentralization and transparency maximizes the accountability of the code-based system. Instead, they often opt for using permissioned blockchains,40 where the degree of decentralization is controlled but still leveraged to provide confidence, auditability, and transparency. In these instances, the balance between centralized control and decentralized benefits becomes a crucial factor in achieving the desired level of trust and efficiency in e-governance solutions. Since many of these efforts are still emerging and in the early phases of development, the lessons learned offer initial insights into how the technology can be integrated into the existing social fabric and how they can be woven into our material realities and daily lives. In the following three case studies, we outline three institution-led

37 Bodó B and Giannopoulou A (2019) The logics of technology decentralization: the case of distributed ledger technologies. In: Ragnedda M and Destefanis G (eds) Blockchain and Web 3.0: Social, Economic, and Technological Challenges. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3330590

38 De Filippi, P., Mannan, M., & Reijers, W. (2020). Blockchain as a confidence machine: The problem of trust & challenges of governance. Technology in Society, 62, 101284.

39 Bodó, B. (2021). Mediated trust: A theoretical framework to address the trustworthiness of technological trust mediators. New Media & Society, 23(9), 2668-2690.

40 Permissioned blockchains, also known as private or consortium blockchains, are a type of distributed ledger technology where access to the network is restricted to a specific group of participants. Unlike public blockchains, where anyone can join, read, and participate in the network, permissioned blockchains require users to have authorization to join, read or write data, and validate transactions.

use cases of blockchain that operate at different spatial scales and complexities aimed at enhancing trust with citizens: (1) country-scale digital transformation in Estonia, (2) city-scale record keeping in Reno, and (3) community-scale civic participation urban planning experiment in Berlin.

Blockchain’s promise as a technology for public interest lies in its potential to simultaneously provide transparency, trust, and privacy. For this reason, it has been rigorously experimented by public institutions over the last half decade in policy areas such as electronic voting systems, land registry management, digital ID creations, and private and public information recording and sharing. Over 100 government-led blockchain projects were being experimented in 40 countries by the close of 2018.41

E-Estonia is often cited as one of the most prominent examples of blockchain implementation in the public sector.42 The origins of e-Estonia can be traced back to the nation’s quest for independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. After gaining independence in 1991, the government of the small Baltic republic, with a population of 1.3 million, faced the daunting challenge of reconstructing the country’s infrastructure, including its communication networks and public services. Recognizing the potential of technology to leapfrog traditional development paths and establish a more efficient and modern society, the government has made substantial investments in building digital infrastructure “from scratch” since the country’s inception. Today, Estonia is one of the most digitally connected countries worldwide, where 99% of all public services are available to citizens as e-services.43 According to official reports, through its digitized public services, Estonia is able to save over 1,400 years of working time and 2% of its GDP annually.44

41 Jun, M. (2018). Blockchain government - a next form of infrastructure for the twenty-first century. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 4(1).

42 Alexopoulos C., Charalabidis Y., Loutsaris M. A., & Lachana Z. (2021). How blockchain technology changes government. International Journal of Public Administration in the Digital Age, 8(1), 1–20.

43 PwC. (2019). “Estonia - the Digital Republic Secured by Blockchain.”

44 Ibid.

The three technological pillars forming the bedrock of e-Estonia are (1) e-ID, (2) X-Road, and most recently, (3) KSI (Keyless Signature Infrastructure) blockchain:

1. e-ID: a secure digital identity card that allows Estonian citizens to access a wide range of public and private sector services securely online (est. 2002);

2. X-Road: a centrally managed distributed data exchange platform that allows public institutions to share data with each other in a secure way (est. 2001);

3. KSI Blockchain: a timestamp system built on a permissioned blockchain used to ensure the integrity and authenticity of data within different data registries (est. 2008).45

The adoption of the KSI blockchain, developed by the Estonian cybersecurity company Guardtime, was partly motivated by a series of massive cyberattacks in 2007, collectively referred to as “Web War 1.”46 These concerted denial-of-service attacks targeted Estonian government, media, and web bank servers amidst a dispute with Russia over the relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn. Estonia’s need to bolster its cybersecurity infrastructure prompted the country to integrate blockchain technology into the architectural foundation of its e-governance system.

The permissioned nature of the KSI blockchain makes it particularly well-suited for applications that require high levels of security and data integrity. In 2012, Estonia became the first country in the world to deploy blockchain technology in production systems with the Succession Registry kept by the Ministry of Justice.47 Since then, the KSI blockchain – a robust cybersecurity infrastructure that is also used by NATO and the U.S. Department of Defense – was integrated into the rest of the e-Estonia governance system to protect sensitive Estonian e-services.48 The KSI blockchain creates tokens for data with cryptographic proof of its properties

45 The system generates a unique, unforgeable fingerprint (hash) for each piece of data, which is then chained together with other hashes in a hierarchical structure. This creates an immutable and transparent record of the data’s provenance and any changes made to it.

46 The Economist. July 1, 2010. “War in the fifth domain Are the mouse and keyboard the new weapons of conflict?” https://www.economist.com/briefing/2010/07/01/war-in-the-fifth-domain

47 PwC. (2019). “Estonia - the Digital Republic Secured by Blockchain.”

48 These include e-Health Record, e-Prescription database, e-Law and e-Court systems, e-Police data, e-Banking, e-Business Register, and e-Land Registry.

(such as time, integrity, provenance, identity, uniqueness) that can be verified and acted upon off-chain in the real world.

KSI’s integration into e-Estonia reflected a seamless weaving into Estonia’s mature product assemblage of e-governance infrastructure and services, which had already become indispensable and deeply embedded in the lives of the citizens. As such, for citizens of Estonia, the implementation of the blockchain was an insertion into an invisible infrastructure that did not introduce disruptions to their daily interactions with e-services,49 but rather made these existing services even more secure and efficient.

Guardtime’s approach to blockchain technology, however, is contrary to that of most public blockchain evangelists who favor using radical transparency and decentralized governance to build “trustless” systems. As stated on the company’s website:

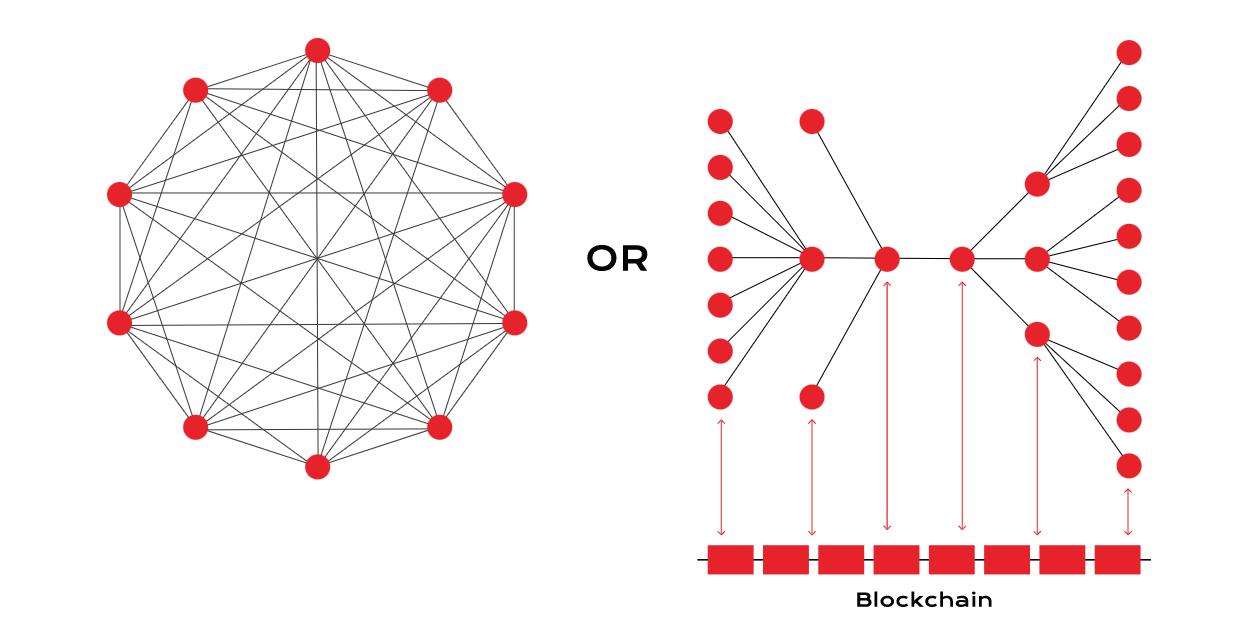

“The early iterations of blockchain involved architectures such as the one of the left below. Every party in the supply chain would run a consensus node and participations would establish governance committees to establish access to what is effectively a shared database. 49 In

This approach is failing universally – the idea that a hospital, an insurance company, a financial institution, or a logistics company needs to know anything about blockchain, let alone run consensus infrastructure, is fundamentally flawed. Our technology takes a different approach. Blockchain is a critical component in all our enterprise solutions but only as the plumbing, deep underground as the infrastructure for generating and transferring tokens. There are no governance committees or shared databases - only software that solves a business problem.”51

This approach in thinking and in technological implementation implies that blockchain serves as a concealed infrastructure that bolsters privacy and security, where decentralization occurs primarily at a technical architectural level, rather than at the governance level. As Semenzin, Rozas and Hassan point out in a recent article, this raises a debate on whether blockchain is being utilized to reinforce central authorities in governance, rather than promoting the decentralization of power away from centralized practices.52

Estonia’s transformation into a fully connected digital society stems from very specific sociopolitical conditions. At the foundational level, as a relatively young country, Estonia’s intricate relationship with Russia and vulnerability to external cyber intrusions contribute to the emergence of a faith-based governmental trust, that stems from warranting cybersecurity and maintaining control over sensitive

51 Ibid.

private data. This foundation of institutional trust lays the basic bastions for a country-wide digital transformation with high levels of public buy-in since the start.

During our interviews, citizens from Estonia conveyed a strong sense of trust in the government, which contributed to their comfort in utilizing digital services provided by the state and allowing the state to gain comprehensive access to their data. This trust is predicated on the understanding that their information will be securely managed and utilized only with explicit permission. Through X-Road, citizens are empowered to monitor the ways in which their data is accessed, as well as the specific individuals or entities granted access, thus ensuring transparency and accountability. In doing so, mutual accountability and reciprocal trust between the state and citizens are created and maintained. Such trust is further reinforced by the citizens’ repeated successful interactions with enhanced efficiency that these digital services consistently offer, ultimately creating a positive feedback loop between faith-based trust and confidence-based trust in the institution.

In contrast to the implementation of blockchain in Bitcoin, which sought to establish an alternative financial system to replace untrustworthy traditional institutions, the integration of blockchain in e-Estonia is propelled by the imperative for an already trusted institution to augment cybersecurity and defend its citizens against external threats, and ultimately increasing the trust in the institution through both alignment of values and successful interactions with trustworthy services.

A city-scaled example with a single use case is Reno’s Biggest Little Blockchain (“BLB”) project. BLB is a record-keeping blockchain for storing data pertaining to historic properties in the City of Reno, Nevada. Launched on September 12, 2022, the project’s primary purpose is to place information from the City of Reno’s Register of Historic Places onto a permissioned ledger to be displayed on a web portal.53

Emerging out of a partnership between the City of Reno – under the leadership of innovation-minded Mayor Hilary Schieve, and New York-based private company

53 City of Reno Register of Historic Places. https://reno.stagingnet.blockapps.net/historicPropertys. As of March 2023, there are currently 21 properties listed on BLB’s register. Information on the BLB include the property’s name, address, ownership details, uses and functions, type of architecture, and historical significance.

BlockApps, Reno’s Biggest Little Blockchain is one of the mayor’s numerous visions for utilizing DTTs such as blockchain to enhance governance processes.54 Built on BlockApps’ proprietary blockchain STRATO, BLB was a simple use case that was completed under a compressed time frame to allow the city to migrate its historic properties data onto a permanent record. For the city, the project was a low-risk, “low-hanging fruit” to experiment with a new technology without introducing disruptions to existing governance processes.

The city’s intention of using a traceable permanent ledger is primarily to exhibit its benevolence and accountability to its constituents by undertaking actions to transfer public records onto a transparent database that can be easily viewed and accessed, thus increasing the trustworthiness of the information recorded on-chain. However, a number of current design features of the platform as well as the implementation process make such a message difficult to communicate:

• The frontend of the website resembles any other government open data platforms, without any visible timestamps for data entry or information about the party responsible for input. Since the back-end of the blockchain is inaccessible to the public, it becomes difficult to demonstrate the traceable characteristics of the underlying system that the city keenly promotes.

• Since BlockApps offered to construct the platform for the city at no charge, the customary public consultation process was lawfully bypassed. This absence of communication with the public resulted in notable resistance and pushback. Certain community members felt excluded from the decision-making process regarding the integration of new technology into public services, countering the government’s initial objective of fostering trust with the public.

• Despite Reno community members identifying inaccuracies in the data input,55 there appears to be an absence of methods for individuals outside of the city government to engage in peer-verification and offer feedback.

54 Sengupta, Kingkini. June 6, 2022. “Reno mayor touts potential of blockchain, NFTs as city embarks on new pilot programs.” Nevada Current. https://www.nevadacurrent.com/2022/06/06/reno-mayor-touts-potential-of-blockchainnfts-as-city-embarks-on-new-pilot-programs/