Connected Digital Society:

Paving Ways for Country-Scale Digital Interoperability in Estonia

Helena Rong

Er Li Peng

Helena Rong

Er Li Peng

Helena Rong

Er Li Peng

Helena Rong is an interdisciplinary designer, technologist, and urbanist. She is a Ph.D. candidate in Urban Planning at Columbia University and a Technology and Public Purpose Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, whose research focuses on the use of emerging technologies such as AI and blockchain for the design and governance of the built environment. She received her Master of Science in Architecture and Urbanism from MIT and her Bachelor of Architecture from Cornell University. Rong is the founder of CIVIS Design and Advisory, a design and research practice based in Boston and Shanghai that engages in multi-scalar and interdisciplinary architectural and urban projects. Her work has been exhibited internationally at the Shenzhen Bi-city Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture, World Real Estate Forum, Future of Architecture Platform, among others.

Er Li Peng is a joint Master in Public Policy and Master in Business Administration candidate at Harvard Kennedy School and MIT Sloan School of Management. Er Li previously worked for five years as a data scientist and management consultant at IBM. She is also involved with grassroots nonprofits focused on food insecurity and economic development in New York City and Maine. Er Li’s policy areas of interest include technology, sustainability, social and urban policy, and the intersection of business and government. Er Li graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in economics and mathematics from Dartmouth College.

The arc of innovative progress has reached an inflection point. It is our responsibility to ensure it bends towards public good.

Technological change has brought immeasurable benefits to billions through improved health, productivity, and convenience. Yet as recent events have shown, unless we actively manage their risks to society, new technologies may also bring unforeseen destructive consequences.

Making technological change positive for all is the critical challenge of our time. We ourselves - not only the logic of discovery and market forces - must manage it. To create a future where technology serves humanity as a whole and where public purpose drives innovation, we need a new approach.

Founded by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, the TAPP Project works to ensure that emerging technologies are developed and managed in ways that serve the overall public good.

TAPP Project Principles:

• Technology’s advance is inevitable, and it often brings with it much progress for some. Yet, progress for all is not guaranteed. We have an obligation to foresee the dilemmas presented by emerging technology and to generate solutions to them.

• There is no silver bullet; effective solutions to technology-induced public dilemmas require a mix of government regulation and tech-sector self-governance. The right mix can only result from strong and trusted linkages between the tech sector and government.

• Ensuring a future where public purpose drives innovation requires the next generation of tech leaders to act; we must train and inspire them to implement sustainable solutions and carry the torch.

For more information, visit: www.belfercenter.org/TAPP

In April 2007, the small Baltic republic of Estonia with a population of 1.3 million faced a series of massive cyberattack. Attackers targeted the nation’s government and financial institutions, causing chaos and disrupting public services for weeks, an episode which has since become widely known as “Web War 1.”1 These concerted denial-of-service attacks targeted Estonian government, media, and web bank servers amidst a dispute with Russia over the relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn. From this crisis emerged Estonia’s unwavering drive to construct a more robust and secure digital society. Estonia’s need to bolster its cybersecurity infrastructure prompted the country to integrate blockchain technology into the architectural foundation of its then decade-old e-governance system. Presently, Estonia’s digital governance system known as “e-Estonia” epitomizes the true potential that unfolds when a nation fully embraces technological innovation.

For the last half decade, over 100 governments in 40 countries around the world have experimented with blockchain for public sector use by the close of 2018.2 The appeal of blockchain for public interest lies in its potential to simultaneously provide transparency, trust, and privacy. E-Estonia is frequently cited as a leading example of blockchain implementation in the public sector.3 The origins of e-Estonia are intertwined with the nation’s quest for independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s and its task of building a strong modern society from scratch leveraging the use of digital technology. Today, Estonia stands as one of the most digitally integrated countries worldwide, with 99% of public services available to citizens as e-services. Official reports indicate that through its digitized public services, Estonia manages to save more than 1,400 years of working time and approximately 2% of its GDP annually.4

In this essay, we conduct a case study analysis of Estonia’s nationwide digital transformation and its use of blockchain technology in its e-governance system. Through a comprehensive review of gray literature, supplemented by

1 The Economist. July 1, 2010. “War in the fifth domain Are the mouse and keyboard the new weapons of conflict?” https://www.economist.com/briefing/2010/07/01/war-in-the-fifth-domain.

2 Jun, M. (2018). Blockchain government - a next form of infrastructure for the twenty-first century. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 4(1).

3 Alexopoulos C., Charalabidis Y., Loutsaris M. A., & Lachana Z. (2021). How blockchain technology changes government. International Journal of Public Administration in the Digital Age, 8(1), 1–20.

4 Ibid.

semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, including the architects of the technological systems and the citizens who use them, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of the project. Our approach evaluates the endeavor from multiple perspectives, encompassing technology, governance, regulatory frameworks, stakeholder involvement, and the underlying values driving the transformation. In the subsequent sections, we initially present a historical and contextual overview of e-Estonia, followed by a detailed analysis of the e-governance project. We then delve into the project’s underlying themes of institutional trust and the discourse surrounding the (de)centralization of blockchain technology. We conclude by extracting lessons learned for countries that are contemplating their own digital transformations.

• Estonia’s successful digital transformation is intrinsically linked to its compact size and capacity for central coordination of resources, its ability to leapfrog to new technology as a young nation, and its heightened awareness of external threats.

• E-Estonia’s technological foundation rests on three main pillars: a digital identification system (e-ID), a data exchange platform (X-Road), and a permissioned blockchain system for enhanced cybersecurity and data integrity (KSI blockchain).

• Blockchains can help enhance institutional accountability, but do not automatically lead to decentralization of power in governance.

• The benefits of data interoperability only manifest when data silos are fully dismantled.

• The philosophies of permissioned institutional blockchains fundamentally deviate from the original anarchist approach in public blockchains.

• Despite its unique historical context, Estonia’s digital transformation offers lessons for other nations and governments, including the need for digital literacy, expanded digital services, investment in infrastructure, and prioritization of cybersecurity, inclusivity, mutual accountability, innovation, and public deliberation.

Estonia’s e-governance system is collectively known as e-Estonia. E-Estonia is often touted as one of the most prominent examples of technological innovation in the public sector.5 The genesis of e-Estonia can be traced back to the nation’s pursuit of independence from the Soviet Union during the early 1990s. After 50 years of foreign domination and upon gaining independence in 1991, the Estonian government faced the formidable task of rebuilding the country’s infrastructure, including its communication networks and public services. Estonia’s aspiration to break away from its Soviet heritage necessitated a transformation from a socialist economy to a liberal, market-based one, achieved through the implementation of new financial regulations and the reform of its research and development systems.6 Against this historical backdrop, the government committed substantial resources to constructing a digital infrastructure “from scratch” and catching up with the West since the country’s inception, recognizing the potential of technology to leapfrog traditional development paths in the absence of legacy systems and establish a more efficient and modern society.

The first prime minister of Estonia, Mart Laar recognized the opportunity to build low-cost, state-of-the-art systems centered on accessibility and efficiency.7 In 1994, a community composed of governmental officials, IT specialists, and academics crafted the strategy document entitled “The Estonian Way to the Information Society” to delineate key principles for the management of modern state information systems.8 Four years later, Estonia approved its inaugural IT development strategy known as the “Principles of Estonian Information Policy,” which established a permanent allocation of 1% of the country’s GDP to IT development in efforts to solve social challenges arising from political uncertainties with IT solutions.9 To bolster the IT infrastructure across government departments, the Estonian government launched a network known

International Journal of Public Administration in the Digital Age, 8(1), 1–20.

6 Centre for Public Impact. September 2, 2019. “e-Estonia, the information society since 1997.” https://www. centreforpublicimpact.org/case-study/e-estonia-information-society-since-1997.

7 e-Estonia. “This is the story of the world’s most advanced digital society.” https://e-estonia.com/story/.

8 Ströbele, Maarit. Leosk, Nele. Trechsel, Alexander H. January 19, 2017, “Two countries, two decades, two outcomes: a brief comparison of e-government solutions in Estonia and Switzerland,” xUpery Ltd. Zurich. http://xupery.com/wpcontent/uploads/2017/08/A-brief-comparison-of-e-government-solutions-in-Estonia-and-Switzerland.pdf.

9 e-Estonia. “This is the story of the world’s most advanced digital society.” https://e-estonia.com/story/.

as EEBone, also referred to as “Peatee” in 1998 to securely connect all government departments, which paved the way for the X-Road system three years later.10

The Tiger Leap Initiative (or Tiigrihüpe) launched in 1996, followed by the public-private partnership project Look@World, were crucial initiatives that expanded country-wide Internet access, closed the digital divide, and improved overall computer literacy. This led to broadband access in all schools across Estonia, and both teachers and students were provided with ICT methodology training as well as access to ICT tools. By 2000, Estonia became the world’s first country to declare internet access as a human right.11 Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, the government channeled resources into offering free, basic computer literacy courses for the adult population, while also establishing 500 public internet access points across the country.12 As a result of these engagement measures, over 90% of Estonians are using the Internet today. 13

10 Kitsing, Meelis. September 2010. “An evaluation of eGovernment in Estonia.” Internet, Politics and Policy 2010: An Impact Assessment conference at Oxford University, UK. http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/ipp-conference/sites/ipp/files/ documents/IPP2010_Kitsing_1_Paper_0.pdf.

11 Psaila, S. B. May 2, 2011. ”Right to access the Internet: the countries and the laws that proclaim it.” https://www. diplomacy.edu/blog/right-to-access-the-internet-countries-and-laws-proclaim-it/.

12 Vassil, Kristjan. June 2015. “Estonian e-Government Ecosystem: Foundation, Applications, Outcomes,” World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends, World Bank. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/165711456838073531/ WDR16-BP-Estonian-eGov-ecosystem-Vassil.pdf.

13 Statista.(2022). “Share of households with internet access in Estonia from 2009 to 2022.” https://www.statista. com/statistics/377683/household-internet-access-in-estonia/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20the%20share%20 of,unchanged%20at%20around%2092.41%20percent.

E-Estonia comprises three main technological pillars: (1) e-ID, (2) X-Road, and (3) KSI (Keyless Signature Infrastructure) blockchain.

Launched in 2002, e-ID is the foundational building block of Estonia’s path to a digitally enabled society. The e-ID is a mandatory national digital identity card14 that allows Estonian citizens to access a wide range of public and private sector services securely online. Issued at birth and valid for life, e-ID provides Estonians with the ability to digitally sign documents or authenticate actions, including accessing personal health records, submitting tax declaration, and participating in online voting during elections.

Around the same time, X-Road was developed as a centrally managed distributed data exchange platform that allows public institutions to share data with each other in a secure way. Using a combination of secure protocols, encryption, and digital signatures, X-Road establishes a secure communication channel between two organizations and allows them to exchange data and services with each other in a private and tamper-proof manner. To use X-Road, an organization needs to first become a member of a local X-Road federation, which is a group of organizations that have consented to use X-Road to exchange data and services within the network with each other. Once an organization has joined the federation, it can register the data and services that it intends to share with other members of the federation. When another organization wishes to access the registered data or services, it sends a request through the secure communication channel established by X-Road. The receiving organization can then validate the request using digital signatures and other security measures, and can choose to approve or deny the request based on its own security policies.15

14

15 Over

The combination of e-ID and X-Road allowed for full-fledged digital transformation in public service delivery in Estonia. The most significant impact of Estonia’s digital transformation is the notable reduction in administrative burden for both the state and its citizens during the provision of public services. This saves them an estimated 820 years of work annually.16 The Estonian government asserts that this decreased workload – attributed to factors like fewer in-person interactions – translates into fiscal savings of approximately two percent of Estonia’s annual GDP in terms of salaries and expenses.17

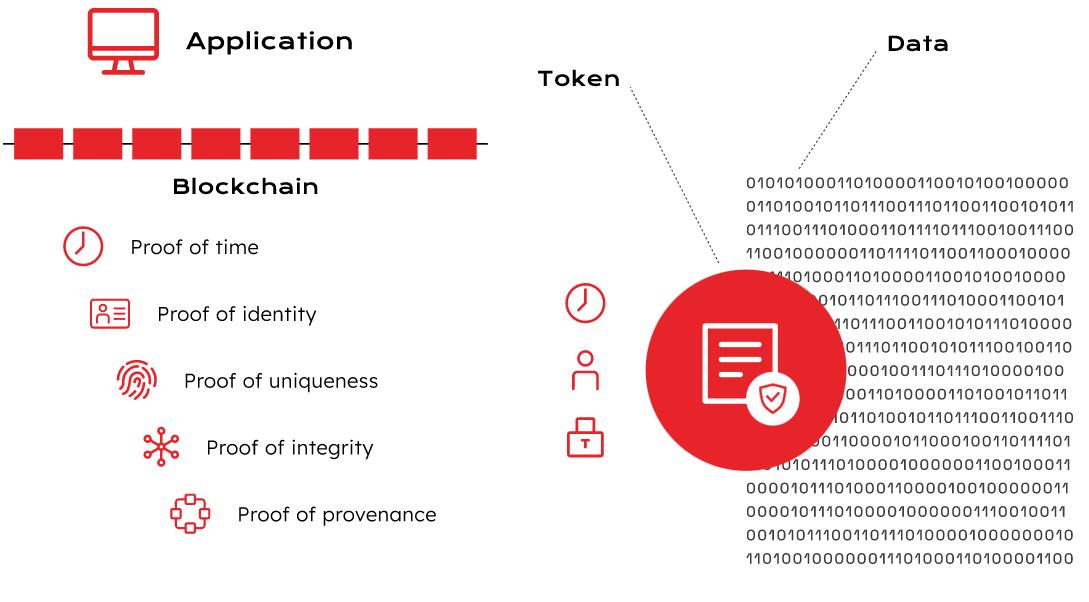

The last key pillar of e-Estonia is the KSI Blockchain, which was developed by the Estonian cybersecurity company Guardtime since 2008 and adopted by the Estonian government in 2012 partially in response to the distressing experience of the 2007 cyber attack. The KSI Blockchain is a timestamp system built on a permissioned blockchain18 used to ensure the integrity and authenticity of data within different data registries. The system generates a unique, unforgeable fingerprint (hash) for each piece of data, which is then chained together with other hashes in a hierarchical structure. This creates an immutable and transparent record of the data’s provenance and any changes made to it. In other words, the KSI blockchain creates tokens for data with cryptographic proof of its properties (such as time, integrity, provenance, identity, uniqueness) that can be verified and acted upon off-chain in the real world.

KSI blockchain’s permissioned nature renders it particularly suitable for applications that require high levels of security and data integrity. Using this infrastructure, Estonia became the first country in the world to deploy blockchain technology in production systems with the Succession Registry kept by the Ministry of Justice.19 Since then, the KSI blockchain – a robust cybersecurity infrastructure also adopted by NATO and the U.S. Department of Defense – was integrated into the rest of the e-Estonia governance system to protect sensitive Estonian e-services. In addition to the Succession Registry, other selected Estonian state organizations backed by the blockchain include the Healthcare Registry,

16 Vainsalu, Heiko. December 12, 2017. “How do Estonians save annually 820 years of work without much effort?” e-Estonia. https://e-estonia.com/how-save-annually-820-years-of-work/.

17 International Peace Institute. May 3, 2016. “Estonia PM: Country Saves 2% of GDP by Going Digital.” https://www.ipinst. org/2016/05/information-technology-and-governance-estonia#10.

18 Permissioned blockchains, also known as private or consortium blockchains, are a type of distributed ledger technology where access to the network is restricted to a specific group of participants. Unlike public blockchains such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, where anyone can join, read, and participate in the network, permissioned blockchains require users to have authorization to join, read or write data, and validate transactions.

19 PwC. (2019). “Estonia - the Digital Republic Secured by Blockchain.”

It is important to note that KSI’s smooth integration into e-Estonia reflects a seamless weaving into Estonia’s mature product assemblage of e-governance infrastructure and services, which had already become indispensable and deeply embedded in the lives of Estonian citizens even prior to the introduction of the blockchain layer. This is an important precondition because from the perspectives of citizens, the implementation of the blockchain was an invisible insertion into an already-functioning infrastructure that did not introduce unwanted disruptions or disturbances to their daily lives and interactions with e-services,22 but rather made these existing services even more efficient and secure.

In recent years, e-Estonia continued to innovate and expand its digital offerings, including an e-Residency program launched in 2014, which allows non-Estonians to access Estonian digital services and start a business in Estonia remotely; and an e-Voting system piloted in 2018 called “i-Voting” linked to the country’s e-ID system. In the parliamentary elections of March 2019 in Estonia, approximately 44% of the votes were cast using the i-Voting online system. This record was surpassed in

20 e-Estonia. (2020). “Frequently Asked Questions: Estonian blockchain technology.” https://e-estonia.com/wp-content/ uploads/2020mar-nochanges-faq-a4-v03-blockchain-1-1.pdf.

21 Guardtime. (2023). “Technology.” https://guardtime.com/technology.

22 In fact, our interviewees expressed that they might not have even been aware of or noticed the change.

the 2023 Riigikogu elections, where more than 50% of the ballots were cast through the same system.23 The principal aim of e-Voting is to expand civic participation and engage young people in the political process. With approximately 200,000 Estonians residing overseas (constituting 15% of the nation’s population), e-Voting provides essential access for this substantial demographic to participate in shaping their government representation.24

Estonia’s ongoing commitment to exploring emerging technologies showcases the nation’s dedication to innovation and its readiness to test new technologies within sandbox environments to enhance governance quality. The e-Estonia platform has established a secure and resilient digital infrastructure that facilitates swift and dependable communication among citizens, businesses, and the government. This effectively minimizes the time and distance between these stakeholders and sets the stage for adopting cutting-edge technologies within the public sector.

23 ERR News. March 4 2023. “Estonia sets new e-voting record at Riigikogu 2023 elections.” https://news.err. ee/1608904730/estonia-sets-new-e-voting-record-at-riigikogu-2023-elections.

24 Mulholland, Patrick. January 25, 2021. “Estonia leads world in making digital voting a reality.” Financial Times. https:// www.ft.com/content/b4425338-6207-49a0-bbfb-6ae5460fc1c1.

IThe theme of institutional trust repeatedly emerged during our interviews. Trust is a complex and multifaceted social phenomenon with varying interpretations on its source and substance.25 According to the literature on trust, trust can be established through both confidence and faith. 26 Confidence-based trust is built on a foundation of repeated positive experiences and interactions, resulting in a sense of reassurance and predictability. This type of trust is established through tangible evidence and personal encounters, leading to a sense of certainty. Conversely, trust based on faith is reliant on shared values and beliefs that cannot be verified through evidence or facts. This type of trust is built on a sense of belonging to a community or institution, as well as shared experiences.27

According to management scholar Graham Dietz, when a trustor faces a potential risk-taking act, they conduct a psychological evaluation of the trustee’s trustworthiness based on their ability, benevolence, and integrity.28 If the trustor perceives the trustee as trustworthy, they become more willing to be vulnerable, leading to a potential risk-taking act. The outcome of this interaction leads to a reassessment and update of that trustworthiness, and the cycle continues and repeats.

In the case of Estonia, the country’s transformation into a fully connected digital society stems from specific and unique sociopolitical conditions. At its core, Estonia, as a relatively young nation, has a complex relationship with Russia and is vulnerable to external cyber intrusions. This has led to the development of a unique, faith-based governmental trust, grounded in the assurance of cybersecurity and the careful management of sensitive private information. This robust institutional trust forms the cornerstone for a nationwide digital transformation, which has seen relatively high levels of public engagement in education from the outset. Throughout our research, interviews with Estonian citizens revealed a deeply ingrained trust in the government, which has in turn fostered a high degree of comfort in utilizing state-provided digital services and

25 Dietz, Graham. (2011) Going back to the source: Why do people trust each other?, Journal of Trust Research, 1:2, 215222.

26 Seligman AB (2000) The Problem of Trust. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

27 Gordon, Eric, and Tomás Guarna. (2022). Solving for Trust: Innovations in Smart Urban Governance

28 Dietz, Graham. (2011) Going back to the source: Why do people trust each other?, Journal of Trust Research, 1:2, 215222.

granting the government comprehensive access to personal data. This trust is rooted in the understanding that their data will be securely managed and used only with explicit consent.

The implementation of X-Road has further empowered citizens by providing them with the ability to monitor how their data is accessed, and by whom, ensuring transparency and accountability. This system fosters a relationship of mutual accountability and reciprocal trust between the government and its citizens. Such trust is continuously reinforced by citizens’ consistently positive interactions with the efficient and effective digital services provided by the state. This creates a virtuous cycle, strengthening both faith-based and confidence-based trust in the institution. The symbiotic relationship between faith-based trust and confidence-based trust in the government and its digital services continues to fortify Estonia’s pioneering digital transformation.

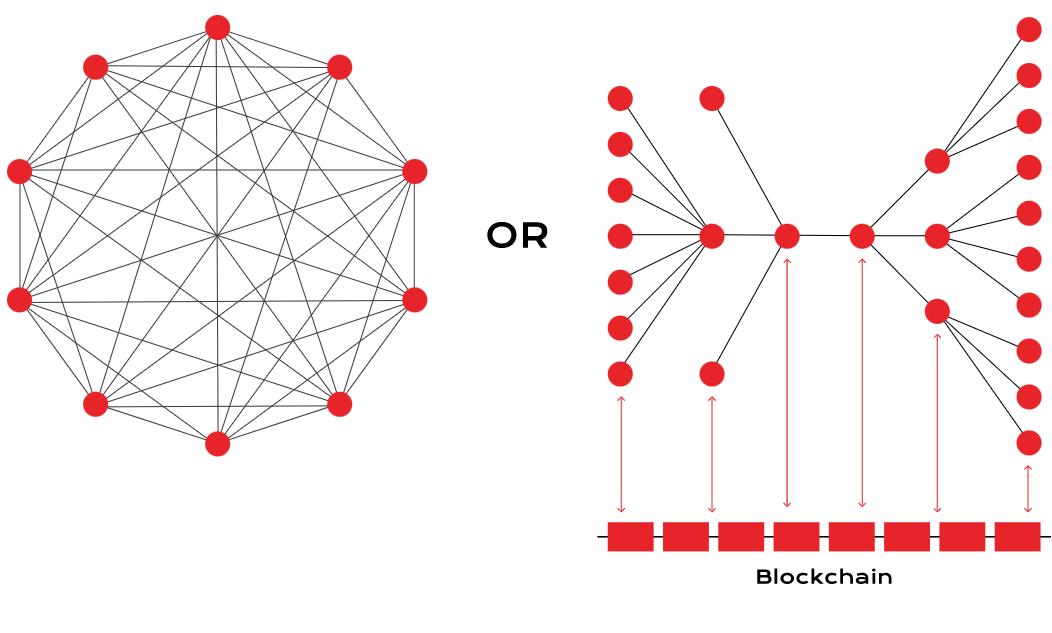

In discussing blockchains – a technology that is often fraught with controversies, debates, and disagreements amongst the general public, practitioners, and academics alike – it is worth to highlight that Guardtime’s approach to blockchain technology as a permissioned system is fundamentally contrary to that of most public blockchain evangelists who favor using radical transparency and decentralized governance to build “trustless” systems.29 From the outset, public blockchains aimed to create a novel trust architecture alternative to traditional centralized institutions by ensuring deterministic outcomes via software code, thereby eliminating the need to rely on untrustworthy intermediaries at both the infrastructure and application levels. Advocates of public blockchains maintain30 that features like decentralization, open-source technology, radical transparency, and the abstraction of issues and solutions through mathematics provide the means to address systemic trust challenges in trust mediation. Consequently, by removing trust in intermediaries via code, blockchain-based systems are often characterized as embodying a “trustless” form of trust.

Contrary to the use of public blockchains such as Bitcoin, which was designed to circumvent the need for untrustworthy centralized institutions, the adoption of a permissioned blockchain in e-Estonia is driven by the imperatives to bolster trust in existing, already trusted, centralized institutions, by emphasizing values such as cybersecurity and privacy. The goal is not to replace or bypass these institutions, but rather to enhance their credibility and reliability. This contrast in underlying philosophies lead to contrasting designs and implementations of the technology that go by the same terminology “blockchain.” As stated on Guardtime’s website:

“The early iterations of blockchain involved architectures such as the one of the left below. Every party in the supply chain would run a consensus node and participations would establish governance committees to establish access to what is effectively a shared database.

30 Public blockchains, also known as open or permissionless blockchains, are decentralized, distributed ledger systems that allow anyone to participate without requiring permission or authorization. They enable transparent, secure, and tamper-proof recording of transactions and data, which are maintained and verified by a network of nodes (computers) through consensus algorithms, like Proof of Work or Proof of Stake.

This approach is failing universally – the idea that a hospital, an insurance company, a financial institution, or a logistics company needs to know anything about blockchain, let alone run consensus infrastructure, is fundamentally flawed. Our technology takes a different approach. Blockchain is a critical component in all our enterprise solutions but only as the plumbing, deep underground as the infrastructure for generating and transferring tokens. There are no governance committees or shared databases - only software that solves a business problem.”31

This approach in thinking and in technological implementation suggests that blockchain functions as a hidden infrastructure that bolsters privacy and security, with decentralization occurring mainly at a technical architectural level rather than in governance. As highlighted by Semenzin, Rozas and Hassan in a recent article, this sparks a debate on whether blockchain is being employed to strengthen central authorities in governance, instead of encouraging the distribution of power away from centralized practices.32

Although the permissioned blockchain – much like its public counterpart – provides a continuous audit trail that fosters enhanced institutional accountability and trustworthiness compared to preceding systems, it notably centralizes governance power. This authority is chiefly held by authorized actors who possess the ability to add to the blockchain and partake in the validation process. The potential risk

31 Guardtime. (2023). “Technology.”

https://guardtime.com/technology.

of this approach lies in positioning citizens solely as consumers of services, rather than collaborators or co-creators involved in the design and decision-making process of service and technology adoption. Despite Estonia’s impressive advances towards digital transformation within its governance, it falls short in fostering public engagement in deliberation and collaborative decision-making, which are fundamental pillars of a fully functional democracy.

Thus, while permissioned blockchains do offer advantages like accelerated transaction times, the removal of gas fees, augmented privacy, and improved governability of the blockchain, they also encounter critiques concerning restricted end user participation and a higher degree of power centralization, which is more susceptible to collusion risks. Some argue that this contradicts the foundational ideal of decentralization inherent in public blockchains, and instead perpetuates traditional centralized practices.33 This deviation arguably strays philosophically from the promise of disruptive decentralized governance and equitable power distribution in decision-making processes.

For many, Estonia’s nationwide digital transformation has been a remarkable success. Implementations of innovative solutions such as digital identity, e-voting, and e-residency have significantly improved the quality of governance and public service delivery. The adoption of permissioned blockchain technology further bolsters cybersecurity, reinforces data privacy, and ensures data integrity. While certain elements of Estonia’s digital transformation offer useful lessons for any public sector contemplating the adoption of innovative technology for governance, it is important to emphasize that various factors specific to Estonia’s context render its digital transformation not so easily and readily replicable in other settings.

As underscored earlier, Estonia’s distinctive sociopolitical conditions and its perception of external threat cultivated a fundamental trust relationship between its citizens and the government that facilitated a smooth adoption of digital services. Given the country’s relatively recent independence, it has been able to bypass entrenched legacy systems, thereby leapfrogging to the adoption of state-of-the-art technology from the outset. The country’s small size and its ability to centrally manage and allocate resources from the top-down also enabled its rollout of universal standards across all government departments relatively friction-free. This effectively achieves data interoperability through dismantling data silos and enabling seamless communication between various data sources, thereby leading to more efficient service delivery.

Implementing such practices is significantly more challenging in contexts with fragmented and federated governance and political structures, due to coordination hurdles across different jurisdictional boundaries and the complexities of diverse laws and regulations. In larger countries like the United States, the substantial levels of diversity and intricate social fabric – characterized by a wide array of languages, cultures, and socioeconomic backgrounds – further complicate the adoption of a uniform digital infrastructure. Ensuring its accessibility to all citizens becomes a colossal task, necessitating substantial financial investment and an extended time frame for successful implementation.

Nonetheless, there are several key lessons that other nations and governments can glean from Estonia’s experience:

1. Promote digital literacy: One of the cornerstones of e-Estonia’s success lies in its significant commitment of resources towards educational initiatives aimed at bridging the digital divide, particularly focusing on more vulnerable populations such as the elderly. As digital services become increasingly prevalent, it is essential for governments to ensure that all citizens possess the necessary knowledge and skills to utilize these services effectively. This could entail the integration of digital literacy into educational curriculums, as well as the provision of training programs for adults.

2. Expand digital services: Governments could take active steps towards expanding the range of services offered digitally. This could encompass a variety of administrative tasks, from tax filing and renewing identification documents to more complex procedures such as voting.

3. Invest in digital infrastructure: Significant investment would be needed to upgrade and expand digital infrastructure, particularly in rural areas or other regions with limited internet access. Investment in digital infrastructure should not only focus on physical improvements like broadband expansion, but also on enhancing the reliability, speed, and security of digital networks. This will ensure that as many people as possible can access high-quality digital services, thus promoting digital inclusivity and participation across all sections of society.

4. Prioritize cybersecurity: Estonia, following the major cyber attack in 2007, has become a world leader in cybersecurity. Estonia’s proactive approach to prioritizing cybersecurity plays a pivotal role in fostering trust between the government and its citizens. Given the increasing threat of cyber attacks, other nations could learn from the Estonian experience and prioritize their own cybersecurity and data privacy measures to protect their digital infrastructure and the personal data of their citizens.

5. Focus on inclusivity: It is important to ensure that digital transformation benefits all citizens. This means making digital services accessible to people with disabilities, offering services in multiple

languages, and addressing the digital divide to ensure all citizens have access to the internet and digital technology.

6. Build mutual accountability: In the e-Estonia model, citizens are empowered to monitor how, where, when, and by whom their data has been accessed and used. This level of transparency fosters a reciprocal trust relationship between the state and its citizens. It is crucial for governments to establish measures that facilitate mutual accountability and provide clear and accessible information to citizens about the usage of their data.

7. Foster a culture of innovation: To keep up with rapidly changing technology, governments should aim to foster a culture of innovation within the public sector. This could involve creating a sandbox environment for experimentation, learning from failures, and encouraging ongoing training and development.

8. Create a space for deliberation: In the case of e-Estonia, citizens were not initially included in the design and decision-making processes regarding new technology adoption. However, it is important to note that the integration of feedback mechanisms can significantly improve these digital services, ensuring they evolve in accordance with users’ experiences and changing needs. To bolster the trustworthiness of both technology and institutions, it is crucial to build systems that are not just for the community, but also with the community through participatory design processes. Fostering trust between institutions and constituents necessitates a culture of trust that is cultivated through open dialogue, collaboration, and transparency. This ethos should be embedded not only in the technology and data handling, but also in the decision-making processes.

Estonia’s digital transformation journey is a remarkable testament to the power of strategic digital governance and the potential of emerging technologies like blockchain. However, as we have outlined, the unique sociopolitical context and the country’s strategic decisions played a significant role in this success. While the Estonia model may not be directly replicable in every context, it offers valuable lessons in promoting digital literacy, expanding digital services, investing in infrastructure, prioritizing cybersecurity, and fostering a culture of innovation and public deliberation. As more countries embark on their own digital transformations, learning from Estonia’s experience can provide invaluable insights to navigate this complex yet promising frontier.