2 minute read

Early mandates: Select Cities Seek Data with Public Policy, While Platforms Resist

Even during the era of “data philanthropy” certain cities started to expect access to sharing economy platform data, increasingly feeling the shortcomings of a voluntary “corporate charity” approach. However, in these early days, sharing economy platforms that had built a brand on “regulatory hacking” were often still heralded by members of the public, not as harmful rule breakers, but as bringing revolutionary and needed services to urban residents and visitors. Data philanthropy approaches had helped platforms enhance this good will with reputations as innovative data philanthropists donating data for the public good, despite not actually sharing data on public agency terms.

With perceived public support, when local governments sought data, platforms did not always play nice, and cities—who still often lagged in leverage and in technical expertise—did not always feel they could prevail in the politics of data. As a result, only a few cities were able to enact regulations mandating data sharing. In my team’s research aggregating as many such policies as we could, we were only able to find data sharing policy mandates from six local governments prior to 2018: California’s Public Utility Commission, Chicago, Seattle, New York, Boston, and Amsterdam—all large, relatively wealthy markets and typical “early adopter” cities or states.

Even policies from these “superstar” cities and states did not come without significant resistance. The California Public Utilities Commission became the first agency to mandate ride hail platform data reporting, enacting their policy in December of 2012. Tellingly, Uber refused to comply, citing concerns over driver privacy, and was fined over $7M49. In 2016, New York City’s Taxi and Limousine Commission proposed a rule change

49 Victor Ngo, “Transportation Network Companies and the Ridesourcing Industry: A Review of Impacts and Emerging Regulatory Frameworks for Uber” (Vancouver: Greenest City Scholars Program, October 2015), https://learn.sharedusemobilitycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/policy-documents-4/Transportation%20 Network%20Companies%20and%20the%20Ridesourcing%20Industry%20-%20Victor%20Ngo%20-%20 Public.pdf.

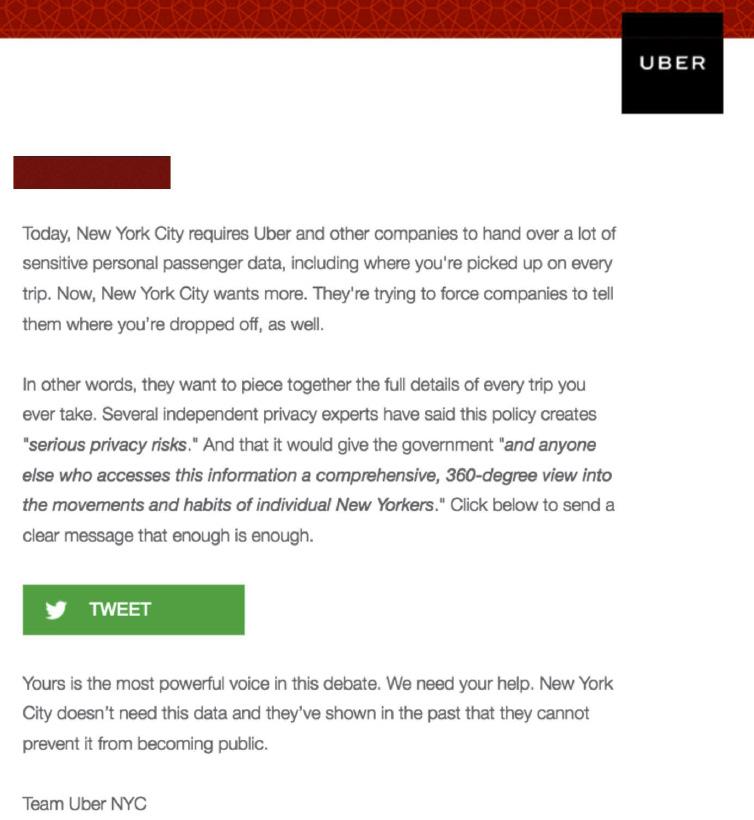

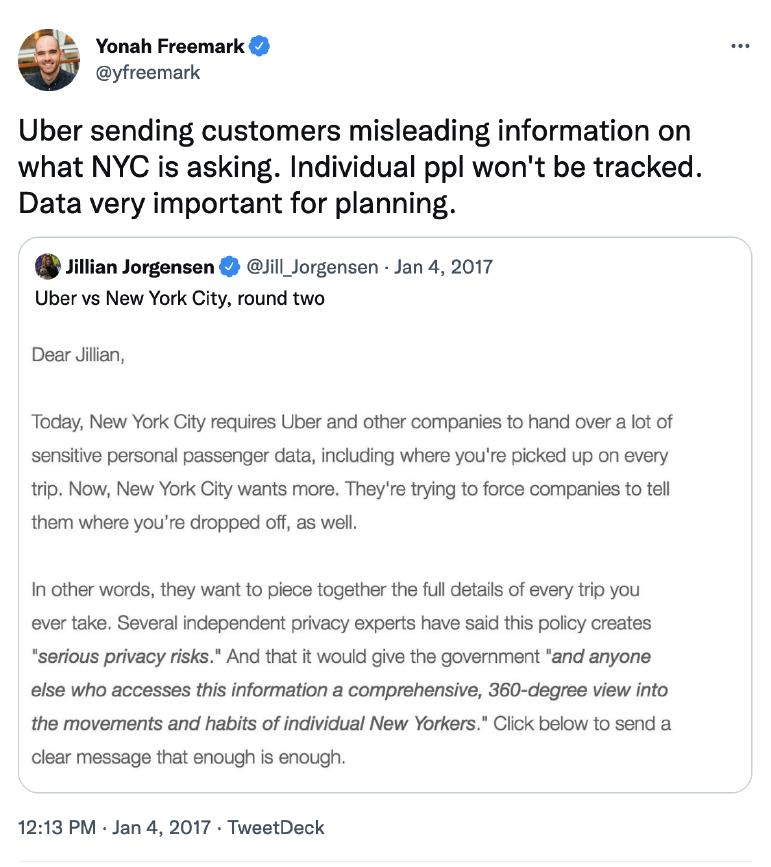

that would require additional data from ride hailing companies50. This included data to help enforce new caps on the number of hours in a day that a driver could work, passed in response to concerns about public safety following fatal crashes involving fatigued drivers. In response, Uber flexed its political might, sending an email to its users warning of privacy and surveillance risks and taking to social media where they coordinated a campaign using the hashtag #TLCDontTrackMe.51

Figures 9 & 10 Uber sends an email to customers (left) stressing privacy risks and stating that “New York City doesn’t need this data”. Uber’s email to customers also encouraged social media posts with the #TLCDontTrackMe hashtag, opposing the proposed data sharing rule. Responding to this, academic researcher and transportation advocate Yonah Freemark chimes in on the data debate with a tweet (right) noting the importance of data for planning and decrying “misleading information” sent by Uber to customers.

50 Beatriz Botero Arcila, “The Case for Local Data Sharing Ordinances,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, April 1, 2021), https://papers.ssrn.com/ abstract=3817894.”plainCitation”:”Beatriz Botero Arcila, “The Case for Local Data Sharing Ordinances,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, April 1, 2021

51 Caroline O’Donovan, “Uber Sent A Creepy Email To NY Riders Ahead Of City Hearing,” BuzzFeed News, accessed April 11, 2022, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/carolineodonovan/uber-creepy-email-nycplan-to-track-rides.