WINTER 2021

COL L E C T ION S A P U B L I CAT I O N O F T H E B E N T L EY H I STO R I CA L L I B RA RY

ECLIPSING THE TRUTH

In 1878, scientists flocked to the western United States to watch a once-in-a-lifetime eclipse. U-M’s own James Craig Watson was among them, hoping to confirm the existence of a planet called Vulcan.

WINTER 2021

Ann Arbor’s State Theater, March 2020. Bentley archivist Brian Williams captured this image, which will be archived as part of the Bentley’s efforts to document the COVID-19 outbreak on U-M’s campus. On the cover: An undated image of a solar eclipse from the Bentley’s Detroit Observatory collection. This eclipse was observed through the Curtis Schmidt Telescope, named for the director of the Detroit Observatory from 1930–1942.

4

contents [features]

[departments]

An Arctic Escape

DIRECTOR’S NOTES

In 1928, Professor William Herbert Hobbs was leading U-M’s Greenland Expedition, studying wind and weather patterns in the Arctic. But when a plane carrying two enterprising pilots went down near his research basecamp, he found himself at the center of a rescue mission fraught with peril.

10 Filling In The Silences

At age 16, José Burgos was sentenced to life in prison. After spending nearly three decades behind bars, Burgos is now free. His story of being incarcerated will be archived at the Bentley thanks to a new partnership with U-M researchers to preserve some of least-heard voices in Michigan.

18 Total Eclipse of the Sun

In 1878, U-M Professor James Craig Watson went west to Wyoming to prove the existence of a planet named Vulcan, thought to orbit a path between the sun and Mercury. What was supposed to be his crowning achievement instead showed the limits of science at the time.

1 Challenging the Interpretations of the Past

ABRIDGED

2 Select Bentley Bites IN THE STACKS

25 Bridge the Gap 26 When Every Box is the Last Box

PROFILES

28 Lifting His Voice BENTLEY UNBOUND

30 Color Our Collections 32 Collecting During COVID-19

DIRECTOR’S NOTES Terrence J. McDonald Director, Bentley Historical Library

Challenging the Interpretations of the Past

UPI/KEVIN DIETSCH

WITH ALL APPROPRIATE POMP and circum-

stance, on June 30, 1913, a statue of Michigan politician Zachariah Chandler was unveiled in the National Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol. This was a singular honor for a significant Michigan politician. Each state is allowed to place only two statues in that remarkable place. Chandler was a very successful Detroit businessman who had been elected mayor of Detroit in 1851, and served as U.S. senator from Michigan from 1857 to 1875, as Secretary of the Interior from 1875 to 1877, and again as senator from 1879 until his death later that year. He was a lifelong opponent of slavery, one of the founders of the Republican Party, a crucial political ally of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, and a protector of the rights of African Americans during the Reconstruction period. And yet, in 2011 that statute was removed from Statuary Hall. Was this an early example of the radical “cancel culture?” Not unless you include the Governor and state Legislature of Michigan on your list of “radicals.” It was they who ordered the removal. And therein lies a tale worth retelling at a time when efforts to challenge names on buildings and statues in parks are underway all over the country, including in Michigan. When the name of a building or statue

is challenged, some worry that the past will be hidden, changed, or damaged, but this is not true. What is being challenged is only an interpretation of the past. When historians talk about the past, they distinguish between two things: primary and secondary sources. When Zachariah Chandler wrote a letter to Abraham Lincoln, he produced a primary source: something constructed in the past by someone in the past. When historians later wrote about Chandler, they were constructing secondary sources: something constructed in modern times based on primary sources from the past. In general, primary sources change little. Secondary sources, on the other hand change constantly. A whole field of professional history, called historiography, exists just to chart the changing interpretations of the past produced by historians and others. But these changes in interpretation have no effect on the past itself, only on our understanding of the past. The value of archival libraries like the Bentley is that they house the relatively unchanging documents produced in the past on which succeeding generations base their almost always changing interpretations of that past. Every statue or named building is a secondary source: an interpretation of the past relevant to the moment when that statue was erected or building dedicated.

(Left) A statue of former President Gerald R. Ford is unveiled at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., on May 3, 2011.

What changes when a statute is moved or a building renamed is that the interpretation of the past of one generation is replaced by that of another. And that could, does, and probably should happen again and again. The Zachariah Chandler story has a happy ending that proves this point. After his death in 2006, various Michigan political leaders began to feel that former President Gerald R. Ford should be honored in Statuary Hall and that a statue of him should replace that of Chandler. This is what happened in 2011, when, with the approval of the Governor and both houses of the Michigan Legislature, Chandler’s statue was moved to Constitution Hall in Lansing on May 2 of that year, and Gerald Ford’s statue was unveiled on May 3, in Statuary Hall. The past lives of neither Chandler nor Ford changed on those days; neither disappeared or reappeared. But the contemporary interpretation of what constitutes a political model did change. When we argue over buildings and statues, we are having an important argument only about the present.

Terrence J. McDonald

Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, Professor of History, and Director BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 1

ABRIDGED

abridg 246 Number of football films (1930–1967) inspected and prepared for the Bentley Digital Media Library.

42 Aviation Mystery In 1939, aviators Chauncey E. Spencer (second from left) and Dale L. White (second from right) flew a biplane on a 10-city tour starting in Chicago and ending in Washington, D.C. They set out to prove that African Americans could be capable pilots, ultimately lobbying for changes in legislation that would allow African Americans to join the U.S. Army Air Corps. The Chauncey E. Spencer papers are archived at the Bentley. We have not been able to identify the three women in the picture, but perhaps you can help us put names to faces? Please email any identifying information to: historyhelp@umich.edu “HE WAS SO METICULOUS, STEADY, CREATIVE, AND EXACTING IN ALL THE WORK HE DID. HE WAS A WONDERFUL COLLEAGUE AND HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE BENTLEY AND TO THE LIBRARIES OF THE UNIVERSITY AS A WHOLE ARE SUBSTANTIAL AND STILL ON SHELVES FOR MANY TO ADMIRE AND APPRECIATE.” Former Bentley Director Francis Blouin on the September 17, 2020 death of James Craven, who worked as a library conservator for more than 63 years and was the longest-serving staff member in U-M’s history. 2 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

Number of new websites archived by the Bentley since March 2020, many of them related to COVID19 and George Floyd protests. See what else the Bentley has been up to in the pandemic in the story on page 32.

POPE AND CIRCUMSTANCE This undated photo of Pope John Paul II comes from the collection of Woodrow W. and Ann Woody, who also brushed elbows (and took the photos to prove it) with Presidents Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, an assortment of Michigan governors and congressmen, and automotive executives.

ged

ABRIDGED

COL L E C T ION S

15 Number of faculty engaged in online teaching in partnership with the Bentley since March 2020. Fifteen is also the number of modules created for teaching using digitized materials. Read more about how the Bentley has worked with faculty to optimize digitized resources on page 26.

179 Number of attendees to our virtual September 2020 Making Michigan history lecture featuring Andrei Markovits and Kenneth Garner discussing The Boundaries of Pluralism: The World of the University of Michigan’s Jewish Students from 1897– 1945. Learn more about this series at: myumi.ch/xmXjl

“They had all this rhetoric about, We’re free and independent out here on the prairie! But then they were almost starving to death when the government-subsidized railroad couldn’t get the train to run.” Bentley Archivist Michelle McClellan in a June 25, 2020 article in The Atlantic titled "We're Living in a Retro-Future," which reflects on the resonances between pandemic life and family life as depicted in the Little House on the Prairie books.

NEVER TOO YOUNG FOR WOMEN'S RIGHTS

DOPE BOOKS

Lucia Grimes (’02 B.A., ’06 M.A.) was a suffragist and leader of the Michigan Branch of the National Woman's Party. Her daughter, Emily, is seen here in 1915, holding signs for women’s suffrage.

The name given by the U-M Athletic Department to the rosters of letter winners from 1860 to the present. The name refers to the “inside dope” or official records.

Lucia Grimes developed a card index filing system that included every Michigan legislator and his attitude toward women's suffrage. In 1916 she was invited to Washington, D.C., to implement her system for the U.S. Congress.

PANDEMIC QUIZ

The efforts of suffragists like Lucia and Emily helped Michigan become one of the first three states to ratify the 19th Amendment on June 10, 1919.

As of October 2020, how many researchers can be in the Bentley’s Reading Room at one time?

Question:

ANSWER: 6

True or false:

NUUK, GREENLAND ROCKFORD, ILLINOIS STANDISH, MICHIGAN RAWLINS, WYOMING WASHINGTON, D.C. Locations visited in this issue.

All researchers are allowed into the Bentley at this time. ANSWER: FALSE. THE BENTLEY IS OPEN TO U-M FACULTY, STUDENTS, AND STAFF.

Question:

What is the longest amount of time researchers can be in the Reading Room? ANSWER: 3 HOURS BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 3

AN A

4 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

COL L E C T ION S

ARCTIC ESCAPE

With the world watching, two pilots went down over Greenland in 1928. Their rescue would hinge on William Hobbs, a professor-turned-adventurer leading U-M’s Greenland Expedition. His papers at the Bentley reveal how, in order to get everyone out alive, he’d have to face peril again and again.

By Madeleine Bradford

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 5

THE SKY WAS CLEAR, THE RUNWAY WAS READY, BUT THE ROCKFORD FLIERS WERE LATE.

NO PLANE ARRIVED. 6 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

HOBBS AND THE BARNSTORMERS The Rockford Fliers were Parker “Shorty” Cramer and Bert “Fish” Hassell, two lifelong aviators; “barnstormers who flew by the seat of their pants and the Grace of God,” in Hassell’s own words. Their stop in Greenland was part of a plan to prove the potential of the Great Circle Route from North America to Europe, by following the Earth’s curve directly between the two continents. They chose a course to Stockholm from Rockford, Illinois, the town that gave them their name. This route was relatively untested. They were planning very few stops for fuel. It was dangerous, but head pilot “Fish” Hassell had gotten his nickname by crashing his plane into Lake Michigan and swimming to shore; he was not afraid of a risky flight. Of course, when plotting a global journey, who better to ask for advice than the Head of Geology at the University of Michigan, Professor Hobbs? An explorer himself, Hobbs knew the world; he’d seen most of it. Moreover, he never shied away from answering questions that were asked of him—or answering ones that weren’t. Hobbs eagerly gave his opinions of other explorers, proclaimed which of his colleagues he believed were enemy sympathizers (accusations that cost those men their jobs during World War I), and shared his thoughts on the best presidential candidate (certainly not Woodrow Wilson, he’d quickly tell you, in 1912). Depending on who you spoke to, he was an overzealous hothead, or a patriot. Certainly, he could never be accused of being shy.

(OPENING SPREAD) COURTESY OF MIDWAY VILLAGE MUSEUM; (CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) HS19724; COURTESY OF MIDWAY VILLAGE MUSEUM; HS19719

As night drifted down over Greenland’s frozen landscape, the landing strip near Camp Lloyd glimmered with lanterns, illuminating the worried faces of the 1928 University of Michigan Greenland Expedition team. They squinted upwards, waiting for the rasping buzz of a monoplane engine, or the flicker of the Greater Rockford’s shadow. Perhaps it would only be another 10 minutes. Another hour. Another two hours. They waited.

Radio signals from the Greater Rockford stopped abruptly over the freezing Labrador Sea, according to the New York Times. A group of churchgoers spotted the plane flying inland near Qeqertarsuatsiaat (a name that roughly translates to “Rather Large Islands”) on Greenland’s southwestern coast, so the plane had likely made it to shore. That was all anyone knew. Worry mounted. Radios tuned in to hear any signals the Fliers might send. Boats scoured the coast, and search-and-rescue teams worked to cover the land. Local hunters searched for the Fliers in the wilderness. Newspapers speculated: maybe the Fliers were stranded, injured, or dead. Maybe they would turn up tomorrow. Professor William Herbert Hobbs, the bristle-bearded adventurer leading the University of Michigan’s Greenland Expedition, knew intimately the dangers a wrecked plane could be facing on the ice. Trekking the Arctic, tracking pilot balloons, Hobbs’ expeditions had hunted information about Greenland’s glacial winds since 1926. Hobbs knew it was a treacherous place to be stranded, and the window of survival was narrowing. A false report said the Fliers had been spotted even farther south—too far away to reach Hobbs and his men alive. Nothing more was heard for days. Then weeks. “After two weeks of this suspense, we became convinced that [they] must have perished,” Hobbs wrote in his autobiography, An Explorer-Scientist’s Pilgrimage. That was when smoke from the Rockford Fliers’ campfire broke the skyline.

COL L E C T ION S

(Opening spread) A crew recovers the Greater Rockford airplane in 1968. The plane originally went down over Greenland in 1928. (Clockwise from top left) The “Rockford Fliers,� a.k.a. aviators Bert Hassell

and Parker Cramer, examine a piece of equipment in this undated photo. Hassell and Cramer pose with the Greater Rockford amid a large crowd of spectators in Cochrane, Ontario, in 1928.

A drawing of a cross-section of the Mt. Evans Observatory in Greenland, where U-M Professor William Hobbs and his team conducted meteorological research.

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 7

Researchers on a boat in Greenland in 1926, from left to right: S.P. Ferguson, Ralph Belknap, Bob Bartlett, Larry Gould, William Hobbs, Paul Oscanyan, James Church.

8 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

survived the sink ing of the ship, the Nakuak.

MAYDAY, MAYDAY

The Rockford Fliers set out for Greenland on August 18 in fine weather. Their first pit stop, in Cochrane, Ontario, went smoothly. Over the Labrador Sea, however, thick clouds bloomed around them; gale winds swung the plane offtrack. Fuel dwindling, they stuttered through the air, dipping dangerously low. They scanned the harsh Greenland landscape frantically for signs of Hobbs’ crew. Eventually, lack of fuel forced them down on the Maniitsoq Ice Cap (“Place of Rugged Terrain”), far south of the landing zone. The world that the Rockford Fliers now faced was sharp and cold, cut by thundering glacial rivers and deep crevasses. Yet they believed they were close to Hobbs’ location, Hassell later told the New York Times. They expected the walk would take a single day. It took two weeks.

Professor Hobbs (middle) poses with Rockford Fliers Cramer (left) and Hassel (right) after the Fliers survived a plane crash and two weeks in Greenland’s desolate wilderness.

(TOP TO BOTTOM) HS5975, HS19722, HS19726, HS19725

(Top to bottom) A 1928 newspaper clipping conveys Hobbs’ account of a shipwreck while trying to help the Rockford Fliers sail to Greenland’s capitol, Nuuk.

So when the Fliers asked for advice about their trip, he responded. One of their refueling stops should be on the coastal flats of Greenland, he told them. As head of the Greenland Expedition, he was in a unique position to help. Hobbs was motivated by more than just altruism. He hoped the Rockford Fliers would prove that Greenland could serve as a stopover for air travel to Europe. He also saw the scientific potential of the flight: the Fliers agreed to bring a meteorograph with them on their journey. For Hobbs, this was a tantalizing potential source of new data regarding wind patterns high above the ice cap. The Fliers could whisk the information from the air as they flew. Hobbs wasn’t the only one invested in the flight’s outcome. The New York Times estimated that 20 percent or more of the population of Rockford, Illinois, chipped in to help buy the Fliers their Stinson monoplane, the Greater Rockford, in a version of early crowdfunding. It took some persuasion. “Nobody would believe us when we told them we wanted to go to Sweden from Rockford the shortest way. . . . They said we were bushed. We drew maps for them on tablecloths and wrapping paper and we argued until our tongues were flapped out,” Hassell told the Evening Star in 1944. The arguments paid off. The plane was purchased. After one false start that ended in a cornfield crash, Rockford residents watched, heads tilted Hobbs and the skyward in late summer 1928, as the Greater Rockford Fliers Rockford disappeared into the clouds.

COL L E C T ION S

NO SMOKE WITHOUT FIRE Professor Hobbs heard it before he saw it: one of his expedition’s little boats, humming in the storm-tossed fjord. Throwing down the pack he’d been carrying to their weather observatory inland, he rushed back to camp to demand explanations. No one had asked permission to head into the fjord. Hobbs was furious. More than that, he was frightened. On the water, a storm was rising. At Camp Lloyd, he was greeted by a group of native Greenlanders who had seen a plume of smoke in the distance. If it was a campfire, the Rockford Fliers might be alive. Hearing that, Elmer Etes, the Fliers’ friend, and Duncan Stewart Jr., assistant geologist, immediately leapt into the expedition’s motorboat and set off into the fjord. Never mind the waves, or the wind. Standing onshore, Hobbs’ dread overtook him; he later called the moment “interminable.” They stood a chance of losing not just the Fliers, but now Etes and Stewart. Sputtering flashes pierced the darkness. First, a flare gun; then a quick signal in Morse code—the Fliers were alive! Hobbs’ men lit a lantern over the camp as a makeshift lighthouse. When the motorboat was near shore, Hobbs and his crew waded into the freezing water. They helped haul the Fliers back onto land. As soon as the Fliers were safe, Hobbs raced to send a message to the New York Times, to tell the waiting world and the Fliers’ families: they had survived! It was a miracle, but none of them knew how much trouble still awaited them. Home free? Not even close.

A LEADER OF SHIPWRECKED MEN Hobbs decided to travel with the Fliers back to Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, along with a portion of the expedition’s crew. Two days after the rescue, all boarded the Nakuak, a motorized sailing ship, or “sloop,” around nightfall. Weary and wave-rocked, they fell quickly asleep. At the helm, near dawn, so did their skipper. With a horrible jolt, the Nakuak cracked open against a reef. Water churned in. Startled awake, some rushed to wedge anchor flukes into nearby rocks, while others scrambled to bring their supplies out of the hold.

Hobbs found himself a leader of shipwrecked men. They were lucky, he knew; they had food, tents, and sleeping bags. Everyone lived. A dinghy with two crewmembers had been sent to get help. Still, after a few days, Hobbs began to fear that the dinghy hadn’t made it. He started the fatal calculations. How much food was there? How many people? How long, exactly, did they have? Just as they were about to begin rationing, the motor sloop Nipisak arrived. Relieved, and exhausted, the men climbed aboard. Hobbs and the Fliers were offered the use of the Nipisak for the remainder of their journey to Nuuk. They accepted. They soon wished they hadn’t. The motor stopped and started, and the winds drove them sharply back and forth between the sea and the reefs. When the Nipisak finally made it through, the delay had cost them. The freighter Hobbs had intended to book for passage toward Copenhagen was already full. They turned to the tramp freighter Fulton instead. The ship held no bunks, but plenty of ore, which clanged thunderously against the metal siding as they bucked through the rough seas. Most of their party slept on the floor, “where they rolled about like peas with the tossing of the ship,” Hobbs remembered. Dishes clattered. Ink bottles smashed. Supplies were jumbled about. They reached Copenhagen safe but shaken. The Scandinavian-American steamship line brought the Fliers back to New York, but Hobbs went separately on the ocean liner Olympic, only to pass through another massive storm. “Only once, when riding out a typhoon in the Sea of Japan, have I seen a more angry sea,” he reminisced. Despite everything, Hobbs and the Fliers believed their trip successful. The Fliers’ runway in Greenland was later transformed, at Hobbs’ recommendation, into the U.S. airfield Bluie West-8 in World War II—one of several such airfields placed strategically throughout Greenland at Hobbs’ advice. Later still, the airfield became Greenland’s Kangerlussuaq Airport. For his work in World War II, France appointed Hobbs a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Researching Greenland’s weather patterns also made Hobbs among the first to record instances of katabatic winds: cool, dense air sliding quickly downhill. The story of the Greater Rockford doesn’t end on the ice. The abandoned monoplane was rescued in 1968 and resides today, restored, in the Midway Village Museum in Rockford. n

PROJECT RUNWAY In 2006 and 2019, expeditions of students and faculty from the University of Michigan and other institutions followed the footsteps of the 1926 Greenland Expedition, studying climate change. Meteorology specialist Professor Perry Samson led these expeditions alongside U-M Professors Mark Flanner, Jeremy Bassis, and Virginia Tech Professor Bob Clauer. Their students saw glaciers crumbling, studied the winds, learned history, and raised awareness about the impacts of climate change.

The base for their work was Kangerlussuaq. The Fliers’ old runway is now a hub of travel in Greenland, receiving visitors and arctic researchers alike. Digital photographs of the 2006 expedition’s work have been donated to the Bentley Historical Library by Professor Samson. He and his colleagues plan to donate additional materials from 2019 as well, including 3-D views of Hobbs’ old weather observatory in Greenland, at the top of Mt. Evans. BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 9

10 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII IIII

FILLING IN THE SILENCES

INCARCERATED INDIVIDUALS ARE SOME OF THE LAST PEOPLE TO HAVE THEIR STORIES AND EXPERIENCES ARCHIVED. THE BENTLEY IS WORKING TO CHANGE THAT

By Lara Zielin

BY PARTNERING WITH U-M RESEARCHERS ON A NEW INITIATIVE THAT WILL PRESERVE SOME OF THE LEASTHEARD VOICES IN MICHIGAN.

years old for shooting twin brothers in a drug deal gone wrong. One of the brothers had died; the other was left a paraplegic. When she contacted Burgos, LaBelle was just beginning her work, collecting information and raising awareness. Eventually, she would sue the State of Michigan to abolish life sentences for juveniles. But at the time, she was just getting started, hoping Burgos would be willing to take a survey and be part of her efforts. This, Burgos says, was when he found hope—and his most joyful moment. “It was a long tunnel, but I finally saw some light,” he says. Burgos found a typewriter and began doing what he could to aid LaBelle’s work. “I was writing letters to everyone I could think of, and sending petitions out.” In prison, he says he found a new community of people who had come to prison as kids, just like him. “It felt good to get back in the fight,” he says. In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that a mandatory life without parole sentence required by a statute for juveniles constituted cruel and unusual punishment. In 2016, in Montgomery v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court decided that the Miller v. Alabama ruling applied retroactively to those currently serving out sentences. In other words, prisoners like Burgos. At Burgos’s resentencing hearing in May 2018, the judge praised Burgos’s growth in prison. He’d earned his GED. He’d mentored at-risk prisoners and trained assistance dogs. He acknowledged his victims and said he’d never stop trying to repair the damage he’d done. Ayman Kaji, the victim of Burgos’s crime, was in support of his release. “If Mr. Burgos can do good out in society, I’m all for it,” he told the court.

José Burgos can tell you when he found joy in prison.

It was 2003, and he was 12 years into a sentence of life without parole. All his appeals had been denied, and he was serving time in a maximumsecurity facility in Standish, Michigan. He was isolated from the general prison population in what’s called “segregation,” and with him were mentally ill prisoners. Day and night, their anguished screams reverberated around him. In lockdown for 23 hours every day, there was no relief from the noise. Alone in his cell, Burgos says he began a conversation with God. “This can’t be it,” he said. “You have to have more for me.” Two weeks later, Burgos received a letter. It was from Michigan attorney Deborah LaBelle, who was advocating for juvenile offenders who’d been given mandatory life sentences. At the time, Michigan had the second-highest number of juvenile lifers in the country. Burgos was one of them, sentenced to life without parole when he was just 16

12 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

After serving 27 years for his crime, Burgos was released from prison in October 2018.

Sharing Stories of Incarceration Burgos’s story of incarceration was documented by the Confronting Conditions of Confinement research team at the University of Michigan. They interviewed Burgos in February 2020 to record his story as part of an effort to document the various conditions, impacts, and costs of being confined in a Michigan correctional facility. Now, a new collaboration between the Confronting Conditions of Confinement team and the Bentley Historical Library means that stories like Burgos’s may eventually be archived for researchers in the future. “It’s our hope and goal that the Bentley will be a steward of the oral histories and written correspondence we collect,” says Nora Krinitsky, director of the Carceral State Project at U-M, which oversees the Confronting Conditions of Confinement team as part of a larger research initiative called Documenting Criminalization and Confinement (DCC). Krinitsky says that being in communication with the Bentley from the project’s early stages helped them know what information to collect—and how. “Archivists at Bentley have helped us understand how to track metadata, how to digitize materials, and how to keep track of everything we’re collecting,” Krinitsky says. So far, Krinitsky says that more than 150 people have agreed to participate in the Confronting Conditions of Confinement project, providing details about their contact with the criminal legal system before prison, the living conditions in the correctional facilities where they are incarcerated, what community is like in prison, what their incarceration means to them, and more. As the COVID19 pandemic has threatened many prison populations, collected stories have included accounts of illness and quarantine as well.

LON HORWEDEL

COL L E C T ION S

Jose Burgos photographed in Detroit in July 2020. BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 13

14 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

COL L E C T ION S

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 15

Full of Silences

“ ”

“If you go to Bentley right now and want to learn about prisons, the best collections are the governors’ papers, but it’s almost exclusively the State’s perspective that’s represented,” says U-M Professor Matthew Lassiter.

people themselves. Most of those voices are excluded from traditional archives. “That’s because, for a long time, archives have prioritized the powerful. That’s been changing, but we feel like incarcerated people are one of the last groups that is beginning to be a priority for archives.” Lassiter says that he was inspired to collaborate with the Bentley on the Carceral State project after bringing cohorts of undergraduates to the archive for more than six years to investigate topics such as environmental activism, Michigan’s anti-Apartheid and anti-Vietnam movements, and policing in Detroit. Each cohort of students then developed an online public exhibit about their research. “ This gave me the idea of working with the Bentley and donating materials from my environmental and police history projects. It’s essentially a process of using the Bentley’s resources to develop research questions from the archives, and especially to identify historical actors that my student research teams can interview, then donating these oral interviews to the Bentley. This will expand Bentley collections and bring the voices of even more political activists into the archives.” Bentley archivist Michelle McClellan has been collaborating with Lassiter and Krinitsky to help make the eventual transition of these materials possible. “The history of incarceration is part of Michigan history,” McClellan says, “and not something to keep separate as an uncomfortable side note. The history of the carceral state intersects with racial justice, gender and the family, economic and political history, education, and more. We at the Bentley are stewards of Michigan’s past. Our role is

Archives have always been full of silences, and they privilege certain voices. In the case of prisons, you’re getting the perspective of the State actors who are controlling the lives and the conditions of the people who are incarcerated, but almost never the experience of the incarcerated people themselves. Most of those voices are excluded from traditional archives.

That’s because, for a long time, archives have prioritized the powerful.

Lassiter is a primary investigator on the research grant funding the DCC work, along with U-M Associate Professor Ashley Lucas (see sidebar). “Archives have always been full of silences, and they privilege certain voices,” continues Lassiter. “In the case of prisons, you’re getting the perspective of the State actors who are controlling the lives and the conditions of the people who are incarcerated, but almost never the experience of the incarcerated

16 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

not just to celebrate the good but to bear witness to difficult histories as well.” For his part, Burgos says he hopes that sharing his story will help future generations of researchers. “Maybe it can inspire kids who will go to school years from now, who are pursuing careers in criminal justice. It’s important that this process, and the people, are all humanized.”

Leaving a Legacy On a sunny day in July, Burgos walks along the Detroit Riverwalk, near the River Front Café. He’s almost off parole, excited to have that part of his incarceration behind him. He talks about his job at the State Appellate Defender’s Office helping prisoners prepare for release in a program called Project Re-Entry. “People were out here fighting for me, and now I can guide guys in the same way,” he says. “I want to give someone that same feeling.” It may be years before Burgos’s story makes its way to the Bentley. Krinitsky, Lassiter, and their collaborators across U-M and local communities are just getting started, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made accessing individuals’ stories more difficult. Even once the materials are compiled and handed over, Bentley processors will need to go through them to catalog everything. Descriptions will be written. Digital materials will be hosted online. Finding aids will be created. It’s what the Bentley does, and it all takes time and care. This doesn’t put a dent in Burgos’s optimism. “I don’t have bad days,” he says. He talks about the book he might write in the meantime, and how words inspire him. “In prison, I thought about books, like, those will last as long as man is on Earth.” He pauses. “And it’s the same thing at the Bentley, I think. I hope my words there will leave a legacy, too.” n

COL L E C T ION S

(Clockwise from left) Art featured in PCAP’s recent 2020 online exhibit includes Flowers by Kimberly Pappas; Childhood Memories by Jonny; Free Dorothy by Marjani Abdur-Rahman.

ART AND INCARCERATION COLLECTING MATERIALS FROM THE PRISON CREATIVE ARTS PROGRAM. By Lara Zielin

Thirty years ago, U-M Professor Buzz Alexander began training students and staff on how to facilitate arts programs in prisons. Theater, creative writing, the visual arts, and music were all represented in this first-of-its-kind collaboration between the U-M community and those impacted by the justice system. What became known as the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP) grew into a large university program that has produced a staggering amount of artistic work over the years from thousands of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals—including paintings, photography, stories, performances, and more. More than 300 U-M students are counted as PCAP alumni, having facilitated a program in their undergraduate or graduate program. In 1996, Alexander traveled to 16 prisons across Michigan to collect art from prisoners inside, which he displayed in an exhibition. Today, the Annual Exhibition of Art by Michigan Prisoners is the largest curated exhibition of art by incarcerated people in the nation.

In 2011, Alexander transferred a portion of PCAP’s materials to the Bentley. This included anthologies of the poetry and short stories produced in Michigan correctional facilities, scrapbooks, and photo albums. Recorded theatrical productions, once on VHS tapes, have been digitized by the Bentley and made available online. “What we are successful with at PCAP is building relationships between people inside and outside of prison,” says Associate Professor Ashley Lucas, who became PCAP’s director after Alexander retired (Alexander died in 2019 at age 80). “We put people in meaningful, ongoing dialogue with people in prison, and they are forever changed.” Although PCAP’s in-person work is currently suspended due to COVID-19, Lucas says that the program has developed a virtual correspondence workshop that will continue to collect the letters and stories of people impacted by the justice system. Eventually, these materials will make their way to the Bentley. “We are grateful for such a well-organized place like the Bentley helping us get PCAP materials into the hands of more researchers,” says Lucas. “It’s a comfort to know someone is taking our work seriously and honoring our contributions.”

L A T TO

18 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

COL L E C T ION S

JAMES

CRAIG

WATSON

WAS

AN

ASTRONOMICAL

GENIUS, BECOMING THE SECOND DIRECTOR OF THE

DETROIT OBSERVATORY AT THE YOUNG AGE OF 25.

ECL IP

OF THE S SE

total eclipse of the sun

IN THE SUMMER OF 1878, HE HEADED WEST TO

OBSERVE A SOLAR ECLIPSE, CONFIDENT HE WOULD

FIND A NEW PLANET. THE STORY OF HIS QUEST—

UN

PRESERVED IN HIS PAPERS AT THE BENTLEY—REVEALS

THE CHALLENGES OF SCIENCE IN THE LATE-1800S AND

By Robert Havey

THE FINE LINE SEPARATING FASCINATION AND 19 FOLLY. BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU w

Watson was renowned, by both his peers and the general public, for his uncanny talent for discovering “minor planets,” now more commonly called asteroids. He had found 22 new asteroids, including six in a single year. But when Watson boarded a westward-bound train in the summer of 1878, his goal wasn’t to find another asteroid. Watson was hunting bigger game. He was looking for the planet Vulcan.

20 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

Tedious Observation Astronomers in the 1800s didn’t have satellites, digital imaging, or computer models to find Earth’s close celestial neighbors. They didn’t even have electric lights. To be a planet hunter in the 1800s involved sitting at a telescope for hours at a time in complete darkness, scanning a tiny section of the night sky for motes of light, all while precisely recording everything in a journal including the exact time and position of the telescope. The next step was to take the observations and compare them to a star chart, a grid map of all the known objects in a particular section of space. If a planet hunter found a speck in the sky that wasn’t recorded on the star chart, they would write letters announcing that a new object was found. Other astronomers might respond with confirmation, having seen the new object in their own telescopes, or, in the worst case, respond that it had already been spotted weeks earlier by someone else. It was this practice of tedious observation and record keeping at which Watson excelled. He was 25 when he discovered his first asteroid, which he named Eurynome. Even at that young age, Watson was already a professor of physics and math at the University of Michigan, and had just succeeded his mentor, Franz Brünnow as the director of the Detroit Observatory. “Watson was a child prodigy and clearly a genius in many fields, including astronomy and mathematics,” said Director of the Detroit Observatory Gary Krenz in an interview. “He was able to do complex calculations like an asteroid’s orbital trajectory in a few hours rather than the days it would take other astronomers.” Watson might have also been a victim (Opening spread) of his own ambition and early success. The 1878 eclipse “One of the criticisms leveled by his photographed in peers was that Watson’s work was Creston, Wyoming, great but not deep,” said Krenz. “For by French artist example, the textbook he wrote was and astronomer used for many years, but compared Étienne Léopold to the one written by Brünnow, it Trouvelot. lacked scientific rigor.” (Opposite page) An It’s also possible that his ambi1846 map of the sotions made Watson a less-than-dillar system shows igent instructor. He once gave every the planet Vulcan

orbiting closest to the sun.

(OPENING SPREAD) “TOTAL ECLIPSE OF THE SUN,” THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY DIGITAL COLLECTIONS, 1881–1882. (OPPOSITE PAGE) COLBY, HALL, AND JONES & NEWMAN: A PLAN OR MAP OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM PROJECTED FOR SCHOOLS & ACADEMIES, LIBRARY OF

P Professor James Craig Watson was already an internationally famous astronomer on July 20, 1878, when he left Ann Arbor to embark on the most important scientific expedition of his life.

Vulcan was thought to exist beyond Mercury in a close orbit to the sun, so close that the sun’s light would overwhelm any light reflected from Vulcan’s surface, making it impossible to detect under normal circumstances. The only way for Watson to observe Vulcan was to find it in the sky during the scant few minutes of a total solar eclipse. Watson arrived in Rawlins, Wyoming, after a two-day train ride. Rawlins was a town founded solely because of the Union Pacific Railroad, a frontier town with nothing but windswept prairie beyond its city limits. The path of an eclipse was going to cut through the western United States on July 27, 1878. The eclipse would reach Rawlins at 3:13 p.m. History would not wait.

COL L E C T ION S

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 21

student in his class a passing grade on the final, including a student who had died early in the semester. But at night in the isolated Detroit Observatory, in the complete darkness, Watson was able to shine bright.

Planet at the Point of the Pen In 1846, the French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier did something astounding: he discovered a planet not with a telescope, but with math. Le Verrier figured out that the only way to account for the uncanny orbit of Uranus, which defied Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation, was for there to be another undiscovered planet acting on it. Le Verrier worked out by hand the grueling equations and sent a prediction of where this planet would be to Johann Gottfried Galle at the Berlin Observatory. Within less than a degree away from Le Verrier’s prediction, Galle found an object not on any star chart. They had discovered Neptune. Not content with one solved celestial mystery, Le Verrier turned his attention to Mercury. Mercury also perplexed astronomers with its orbit, which, like Uranus, defied Newton’s equations. Again, Le Verrier predicted a theoretical planet, this time in between Mercury and the sun. He named his planet “Vulcan” after the Roman god of fire and again waited for confirmation.

Separation Anxiety The Railroad Hotel in Rawlins, Wyoming, was full to bursting with scientists and press. The town had been hastily constructed just a decade before to accommodate the Union Pacific trains that rolled through at a constant clip. Watson was one of the late arrivals. He only brought two things with him: his wife, Annette, and the “Comet Hunter” telescope he had borrowed from Michigan State Normal School (now Eastern Michigan University). The Comet Hunter was a newer and bigger telescope with better optics than U-M’s Comet Seeker. Watson wasn’t the only celebrity among the dust and tumbleweeds. Thomas Edison had come to test his new invention, the tasimeter, a device he claimed could measure temperature from distant objects. (The device only partially worked and Edison, who held more than 100 patents at this time, didn’t bother to file one for the tasimeter.) All of this attention on the eclipse provided an opportunity for American scientists to prove to their European colleagues that they could conduct important research. Total solar eclipses are rare events and

22 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

often don’t appear in places ideal for viewing. With the eclipse passing through the heart of the western United States, the pressure was on to produce results. “Post-Civil War American science was small but emerging, and astronomy was a big part of that,” says Krenz. “At the time, only a handful of American scientists could be considered worldclass, but Watson was among them.” The time leading up to the eclipse did not go as smoothly as Watson would have liked. The telescope he brought lacked setting circles, or circular dials crucial for calibration. Astronomers need to know two coordinates—declination and right ascension—so they can know precisely where they are looking in the sky. Without the circles, there would be no way to be certain that any object Watson saw wasn’t just a previously discovered star. Watson had to commission a local carpenter to cut two wooden circles to use as makeshift parts. The day of the eclipse came with a nearly cloudless sky. For reasons unknown, Watson suddenly decided that Rawlins was an unacceptable location to view the event. Watson and Annette packed the equipment, left Edison and the others, and moved down the rail line a few miles to a tiny train depot named Separation. Watson and Annette lugged their equipment almost a mile through thorny brush to join another small group of scientists who were busily preparing. Somehow Watson was able to set up everything in time. At 2:34:16.4 p.m., an undulating darkness crept over the land from the north. Watson couldn’t let himself get caught up in the eerie beauty. Every second of the eclipse was precious. As the shadow passed over the assembled scientists, Watson got to work. Captain William H. Bisbee of the U.S. Naval Observatory was

COL L E C T ION S

THE ACCIDENTAL DISCOVERY OF THE STAR OF CHINA’S FORTUNE

CARBON COUNTY MUSEUM; (TOP RIGHT) HS13373

James Watson (sixth from right) joins scientists including Thomas Edison (second from right) in Wyoming in 1878 to observe a solar eclipse in hopes of confirming the existence of the planet Vulcan.

in charge of marking time for the group, calling out every 10 seconds. Watson began methodically scanning the sky, starting with the sun and looking out in a precise pattern. Nothing for the first minute 30 seconds. The eclipse was half over. Then, finally, something came into focus. Watson saw a reddish object. It didn’t look like a star and didn’t have the tell-tale tail of a comet. He carefully marked the position of his telescope on his makeshift wooden circles. In the final minute of the eclipse, Watson found another object he could not identify. With just seconds left he didn’t have time to check its position against other stars, but was able to mark it down. The blazing July sun reappeared. Watson was able to relax. He had done it. He found not one, but two Vulcans.

Down a Well Watson was hailed as a hero across the country. America had discovered a planet of its own. “PROFESOR WATSON FINDS VULCAN” was the headline in the Laramie Daily Sentinel, one of the first of many papers exhorting Watson’s find. But as the massive work of compiling the observations of researchers and amateurs began, doubt crept in. No one among the hundreds of eclipse watchers had seen either of Watson’s Vulcans. An amateur astronomer, Lewis Swift, stepped forward to say he had also seen the two objects, but later had to rescind his report when he discovered an error in his calculations. The controversy put Watson’s crowning achievement in doubt.

In 1874, Watson was commissioned by the National Academy of Sciences to observe the transit of Venus in Beijing, China. Watson led one of eight American expeditions sent abroad to view the brief few minutes when Venus would be silhouetted against the sun. The primary goal for the Academy was to use data gathered from the expeditions to improve their calculation of the distance between the Earth and sun. Watson arrived in China months in advance and began to set up his equipment. On October 10, two months before transit would occur, Watson discovered his 16th asteroid. This time, it was an accident. While observing the night sky around Pisces, Watson saw an out-of-place object that he later confirmed was indeed a new “minor planet” (the name for asteroids at the time). This was an incredible feat considering he was on the other side of the world from his Detroit Observatory, and that he noticed the asteroid was out of place not by consulting a star chart, but by his memory of that segment of sky. Watson included his account of the discovery in the expedition’s official report, including a grand diplomatic gesture to their hosts: “This being the first planet discovered in China, I requested Prince Kung, regent of the Empire, to give it a suitable name,” he wrote. “The name determined upon by Prince Kung is in Chinese characters the following: 瑞華星. The name stands for Juewa, or more fully Juc-wa-sing, which means literally Star of China’s Fortune. It is now recognized by astronomers by its Chinese name.” The name is still used today. BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 23

C. H. F. Peters, Watson’s planet-hunting rival, published a scathing critique in the leading astronomy journal Astronomische Nachrichten. Despite the controversy, Watson was able to leverage his notoriety into a job offer from University of Wisconsin. U-M said publicly that they tried to retain their star astronomer, but Krenz thinks it’s possible they didn’t try hard enough. “The great innovation in astronomy at that time was photography and spectroscopy, and the Detroit Observatory just wasn’t set up to do those things,” says Krenz. “We have records of Watson requesting funds from the Regents for a spectrometer, but he was denied. He got to build a brand new observatory at Wisconsin.” Watson arrived on the University of Wisconsin’s campus filled with ideas. He wanted to dedicate the next phase of his career to confirming his observation of Vulcan. He even designed an observatory addition with a telescope deep below ground level, looking up at the sky through a hole. The idea—a very wrong idea, as it happens—was that the light from the sun wouldn’t reach the telescope in the hole and therefore daytime observations would become possible.

Watson never got a chance to use it. He died of peritonitis in November 1880 at the age of 42, less than a year after he left Ann Arbor.

HISTORY IN PIECES

➊ LENS

Everything is Relative So what of Vulcan? Other astronomers continued the search for it or any other inter-Mercurial planets during the eclipses of the next half-century, but with no success. The orbit of Mercury remained a mystery. It’s unclear exactly where Watson went wrong. It’s possible that between the wooden setting circles, the rush of the last-minute location change, and/or the narrow observation window, Watson saw a known object but had the coordinates wrong. The solution finally came once again via a pen rather than telescope. This time the pen was wielded by Albert Einstein. Einstein’s theory of general relativity refined Newton’s laws and provided an explanation for Mercury’s strange orbit. Einstein’s theory was dramatically confirmed by two groups of astronomers measuring the bend of light around the sun during a total solar eclipse in May 1919. n Sources for this Story:

The James Craig Watson papers, the Detroit Observatory collection, and the book American Eclipse by David Baron.

The Fitz refractor telescope was one of the best in the world The most critical component when it was first installed in the Detroit Observatory in 1857. in any refracting The Fitz has been restored and will be a main attraction when telescope, the the Detroit Observatory reopens in 2021. Until then, let us WEIGHT lens gathers and show you around the fundamental parts of this incredible S ETTING This is an adjustfocuses light from ➌ CIRCLES piece of equipment (still a marvel of engineering, even by able weight that distant objects. These adjust the today’s standards). balances the teleThis 12-5/8” position of the scope and helps lens is the last telescope in two keep it from movone ground by ways: right ascen- ing while observa➊ renowned telesion is the sidescope-maker Hen- to-side movement tions are made. ry Fitz, still in its of the telescope; ➏ MOUNT original condition. and declination is The telescope is mounted on a the up-and-down ➋ ➋ TUBE 4-ton limestone direction. Light coming in pier which sits on through the lens ➍ EYEPIECE 60 feet of brick has to travel a This is where the masonry extendspecific distance lens focuses the ing 15 feet below ➌ to be properly in ➌ light from the grade. focus (think of a distant object and magnifying glass makes an image ➏ on a sunny day). ➎ ➍ that an astronomer 24 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

HS3791

The 17-foot tube allows that to can happen without observe. interference from ➎ COUNTER– outside light.

I N T H E S TA C K S

COL L E C T ION S

Bridge the Gap By Robert Havey

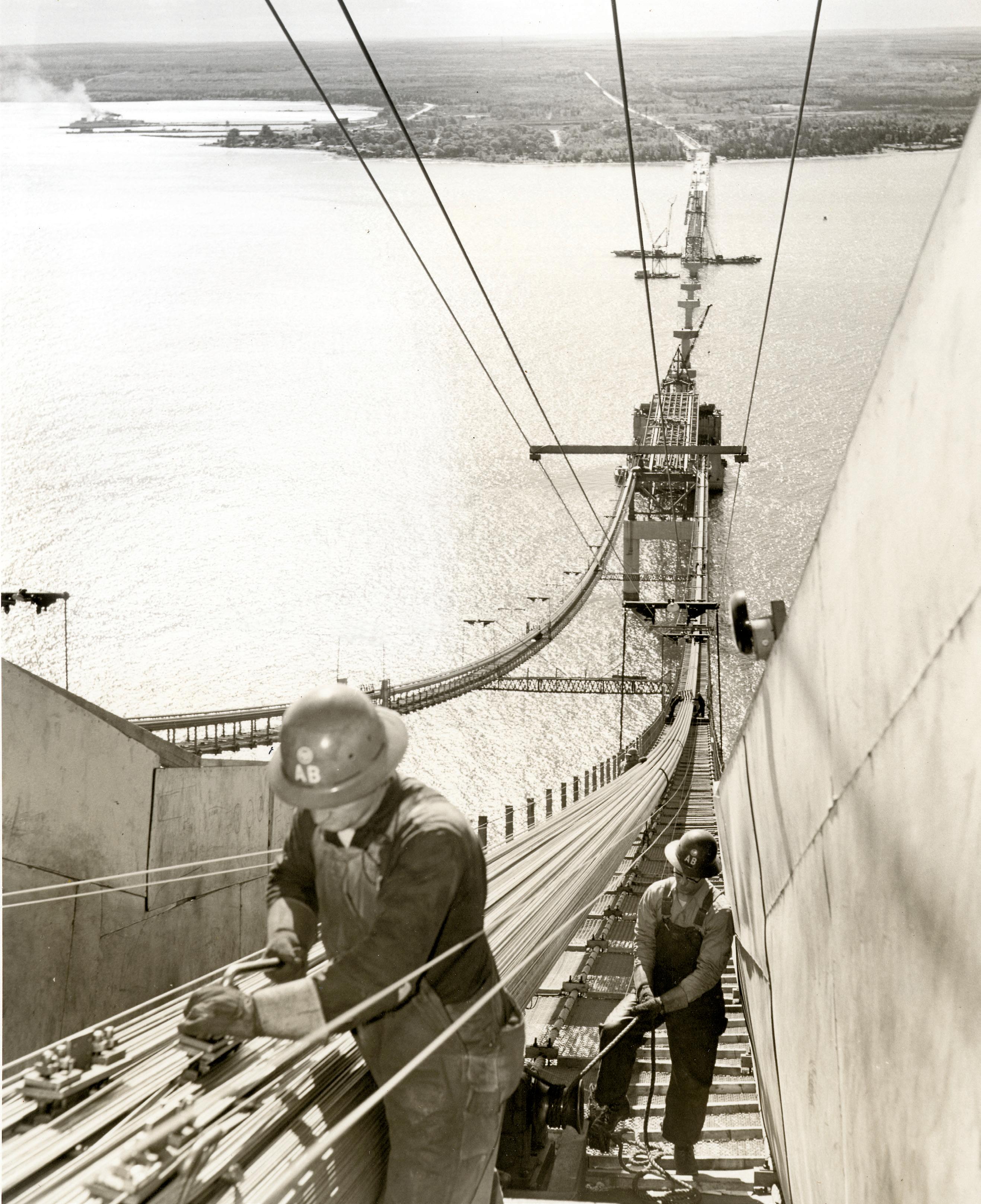

THE PLAN TO BUILD A BRIDGE across the Straits of Mackinac began in earnest in the 1880s. Northern Michigan’s population was exploding, and the ferries that brought people and goods between Michigan’s two peninsulas were crowded and increasingly inadequate. The dedication of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 proved that a suspension bridge of such a large size was possible. More than 70 years later, the Mackinac Bridge was completed. What happened in the meantime? A collapse of the U.S. economy in 1893, a World War, a more devastating collapse of the U.S. economy during the Great Depression, and another, even larger World War. Construction on the Mackinac Bridge finally began in 1954. When it was completed in 1957, its 3,800-foot span was the second-longest in the world, just behind the Golden Gate Bridge. But, as the members of the Mackinac Bridge Authority were quick to point out, if you measure between anchorages (where the bridges are secured to land) instead of the distance between the main towers, the Mackinac Bridge was, in fact, the longest.

BL005763

The Bentley has many collections relating to the history of the Mackinac Bridge, from its fundraising, design, construction, maintenance, and current use including the Mackinac Bridge Authority collection, the James H. Cissel papers, and the Prentiss M. Brown papers.

Construction on the Mackinac Bridge began in May 1954. The Paul Bunyan Bridge Builders adjust cable wire in this image from the William Ratigan collection. BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 25

I N T H E S TA C K S

When Every Box is the Last Box At the start of the pandemic, students and faculty from U-M’s History Department collaborated with Bentley archivists to find creative ways to produce a successful research project, even without physical access to archival materials. By Alexander Clayton, Henry Cowles, and Gregory Parker

IN THE ARCHIVES, THERE’S ALWAYS THAT LAST BOX. The one you meant to check—but didn’t. Maybe the reading room was closing and you told yourself you’d request it first thing the next morning. Or you remembered it over lunch and made a note to see it when you sat back down. But there were other boxes. You forgot.

26 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

The last box could contain anything. A key connection for your argument, a biographical detail you knew you needed. Or even the proverbial smoking gun, the ironclad proof that Dewey really did defeat Truman. But the thing about the last box is that you never do get to check it. It’s elusive. Because after that last box, there’s always another last box. But what if every box were the last box? What if you never got to see any boxes— and still had to do the hard work of history? In answer to that question, this past

spring, a small History Department team worked with Bentley archivists to redesign and reimagine a collaborative research project—finding a way for the research and work to continue, even though the archives were closed and students, faculty, and staff were all working remotely. The project was part of Michigan in the World (MITW), a paid undergraduate internship program in which students develop online history exhibits. Under normal circumstances, MITW teams work side-by-side throughout the spring term, poring over documents together to tell part of U-M’s history. This spring’s topic, “Mental Health at Michigan,” was designed to make use of the Bentley’s rich holdings of administrative reports, faculty records, and alumni files, among other sources. But with the Bentley closed to the public and the University mandating remote work whenever possible, the team had to pivot. The project would remain collaborative and rooted in archival sources, but the nature of both collaboration and the archive was expanded.

LARA ZIELIN

SWAPPING SOURCES In the past, students would have collaborated in the archive, swapping letters between deans and scrutinizing class photos to find their historical actors. Tangible interaction with manuscripts is hard to replace, but a similar dynamic emerged in the digital space. Each of the five undergraduate fellows was assigned their own “character” from the history of mental health at Michigan, someone they could track through the archive on their own. They followed students, faculty, and administrators, exploring the ways in which race, gender, sexuality, and nationality all influenced the experience and treatment of student mental health. Bentley archivists guided students’ searches to the library’s extensive digital collections. Students traded articles from the online archive of the Michigan Daily and linked to photographs from the Bentley Image Bank over Zoom. One letter from the Harlan Hatcher Papers was traded back and forth between the fellows multiple times. A rotating peer review system not only improved the fellows’ writing, but also

BUT WHAT IF EVERY BOX WERE THE LAST BOX? WHAT IF YOU NEVER GOT TO SEE ANY BOXES—AND STILL HAD TO DO THE HARD WORK OF HISTORY? revealed even more connections between their respective stories.

DIGITAL NEEDLES, DIGITAL HAYSTACKS COVID had set a hard line around the physical archive. But this blurred other lines: between the research and writing processes, between the fellows and their characters. At home, students sifted through catalogues and search results, looking for digital needles in digital haystacks. Online search engines proved powerful and destructive at once: By allowing students to see a single name across thousands of newspaper articles, it was both easier and harder to reconstruct the lived reality of the historical actors. This is especially true when those actors come from marginalized groups, when the process of digitization adds another layer by which certain voices are amplified or silenced. The case of Edward Dalton, a Black graduate student in social work, is one example. Two years at U-M, from 1939– 1941—among a student population that was almost entirely white—yielded only one available image, two Michigan Daily articles, and one mention of a psychotherapy practice in New York. Dalton’s relative absence from the archive could have been a drawback in telling his story, but it instead became central to it. From his birth in Alabama, studies at U-M, and career in New York, Dalton’s life tracked the Great Migration, housing segregation, and the Harlem Renaissance. In other words, the limits of the archive opened up a wider story of inequality and opportunity. Turning to online resources also meant accessing the excellent public history that was already available, including in the online U-M Heritage Project stories and past MITW initiatives. Take Deborah Bacon, U-M’s final Dean

of Women and a key figure in the university’s history. In 1961, facing increased pressure from students and university administrators about her strict policies governing the lives of women students outside the classroom—including dress codes, curfews, and even “gentleman callers”—Bacon resigned. It was hard at first to imagine saying something new about someone so well-documented. But the same sources that had made Heritage, Michigan Today, and MITW stories possible—for example, Michigan Daily articles about Bacon’s early life, and a letter she wrote to President Harlan Hatcher documenting her intervention to discipline two women caught in bed together—could be repurposed and reinterpreted for a history of mental health. Evidence of Bacon’s influence for one historian became, for another, data about university climate and its support for mental health (or lack thereof). The case of Robert Stacy afforded a similar opportunity. He was a graduate student convicted of arson in a fire that destroyed the original Haven Hall in 1950, and his story was told on the U-M Heritage site. But rereading the sources in the context of Stacy’s struggle with mental health highlighted another aspect of his story: the ways various institutions, from the Veterans Administration to the university itself, failed to support him. History is never over. Even for the most documented figures, something remains to be said, a dimension of their lives or their world remains to be revealed. This spring, mental health became a lens through which existing histories and well-known figures appeared in a new light. Every archive has silences, and those silences often reproduce social and political marginalization. And all history is based in collaboration—during research or writing, in the reading room or online. We may never find that last box. But we’ll keep looking. View the “Mental Health at Michigan” exhibit online at: myumi.ch/mn5EP

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 27

I N T H E S TA C K S

COL L E C T ION S

PROFILES

Lifting His Voice Willis C. Patterson’s newly donated papers at the Bentley document a tireless fight for African American music to take its rightful place in the vocal canon. By Lara Zielin

IN 1965, WILLIS C. PATTERSON was a young, talented Fulbright Scholar who was singing in “Amerika Houses” across Germany. Each

28 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

night he’d perform Brahms, Schubert, and Italian opera to rave reviews. That is, until a reviewer in the town of Bad Godesberg questioned why Patterson, an African American performer from the United States, would come to Germany “to sing repertory that Germans have already heard many times by equally (and often more) competent singers.” The reviewer suggested instead that Patterson perform “songs of his own racial heritage and from his own country; songs from Broadway musicals, folksongs, spirituals, and art songs.” Patterson was shocked and upset. In

his autobiography, The Unlikely Saga of a Singer from Ann Arbor, Patterson writes how he felt the reviewer’s words were “designed to put me in my place as a ‘proper’ Black singer.” As he reflected on the remark, however, he realized there was some merit to it. “I thought the criticism was, indeed, legitimate in that the concert did not contain music from my own heritage.” However, he bristled at the idea of performing spirituals, Broadway songs, or the few art songs he knew from white composers. But art song compositions from African American composers? Those piqued his interest. Patterson’s decision to research and sing African American art songs would propel his performances and work in new directions. It would change the curriculum at U-M’s School of Music, Theatre, and Dance (SMTD) in perpetuity. Decades later, after a distinguished career as a scholar, performer, administrator, and teacher, Patterson’s materials showcasing the discovery and the history of African American art songs would be archived at the Bentley Historical Library, along with other materials from his extraordinary achievements. The Bentley welcomed Patterson’s materials in September 2020 through a virtual event held in conjunction with the African American Music Conference. The event celebrated Patterson’s 90th birthday and honored his extraordinary contributions as well as the music he helped bring out of obscurity—and now, into the archive.

with the hope that such an effort might begin the process of filling a void.”

CHANGING TO THE CANON

“AN EPIPHANY FOR ME” Patterson was born in Ann Arbor in 1930 and, at age 19, joined the Air Force in part to obtain money for a college education through the G.I. Bill. In 1954, he transferred to the U-M School of Music from Eastern Michigan University (then called the Michigan State Normal College) without any formal music training. However, he thrived at U-M and graduated in 1958 with a bachelor’s degree in voice performance, then went on to complete a master’s degree in music in 1959. He was offered and accepted a job at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and moved there with his wife, Frankie Bouyer, a mathematics teacher whom he married in 1958. Patterson says he relished being surrounded by Black colleagues at Southern University. “I was born and raised in Ann Arbor where persons of academic accomplishment of my color were rare,” he says. “This was an epiphany for me.” He taught at Southern University for two years, then became a professor at Virginia State College in Petersburg, Virginia. By 1965, he was in Germany on his Fulbright Scholarship. Mere weeks after his upsetting review in the Bad Godesburg paper, he performed two African American art songs—“Songs to a Dark Virgin” by Florence Price and “Soliloquy” by John W. Work—for the first time in front of a German audience. Patterson writes that he became “committed to the goal of developing my own collection of African American art songs

An art song is, by definition, written by a composer who uses poetry as the basis for the lyrics, then uses instrumental accompaniment to support the lyrics, thereby creating a song that is a unified whole. (Compare this with a folk song, for example, where the lyrics or melody might change spontaneously.) There were plenty of African American art songs when Patterson went searching for them in the late 1960s and early ’70s— but they were difficult to find. The only book on the subject had been written in 1947 by a Detroit Public Schools teacher named Edgar Rogie Clark. Patterson reached out to Clark, along with myriad others, scouring archives, libraries, and private collections for songs. In 1968, he returned to Ann Arbor to become the first African American faculty member in the history of the School of Music, Theater and Dance. By 1972, he had a collection of African American art music he felt could be published. Patterson writes in Unlikely Saga that publishing African American art songs hadn’t been done by anyone at U-M or a comparable institution, and he felt it would contribute to the canon of music in a significant way. Patterson’s Anthology of Art Songs by Black American Composers was published by E.B. Marks Music Publishers in 1977. “When a collection as important as [this] comes along, it should stir more than the usual amount of interest in musicians of all varieties,” wrote Donald Ivey in Black Music Research Journal. SMTD Professor Louise Toppin, who organized the African American Music Conference in Patterson’s honor, says that “this historic anthology continues to inspire the study of African American art song today as much as it did when it was first released.” In 2002, Patterson self-published The Second Anthology of Art Songs by African American Composers, as well as a collection titled The New Negro Spiritual. These works are part of Patterson’s lifelong advocacy for and contribution to a

more diverse SMTD curriculum—a goal he worked toward during his 30 years as a SMTD faculty member, 20 of them as associate dean. Among his many accomplishments, he instituted a course for voice majors to study music by African American composers. Toppin still teaches the course today. “Historically, nowhere else in the country was there a course like this taken by music majors,” says Toppin. “Many other schools have not made this a priority.” From 1969 to 1975 Patterson was the director of the U-M Men’s Glee Club. He served as president of the National Association of Negro Musicians and organized the first Black American Music Symposium at the University of Michigan in 1985. He also published The Saints Among Us, a book about the community of people in Ann Arbor who helped African American youths like himself during the Great Depression. These activities and more are documented in his Bentley collection. “The extraordinary breadth of Professor Patterson’s career makes his collection an invaluable addition to the holdings of the Bentley,” says Terry McDonald, director of the Bentley. “Any researcher will now be able to trace his search for African American art songs and other important contributions from his incredible career.” “I am proud of my role in . . . the greater cultural and racial diversification of our [SMTD] community,” Patterson says. “I have gained a deep sense of pride in the role I have been permitted to play.”

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 29

PROFILES

COL L E C T ION S

B E N T L EY U N B O U N D

Color Our Collections Every year in February, libraries, archives, and museums all over the world share free coloring pages based on materials in their collections through an event called #ColorOurCollections. Inspired by this idea, we gathered some historic football program covers with the goal of creating our own coloring page. It was a hard choice, but eventually we settled on this cover from the November 1968 game against Ohio State. Grab your pencils, paints, or crayons and enjoy. Feel free to share your finished pieces with @UmichBentley on Facebook or Instagram!

30 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

B E N T L EY U N B O U N D

COL L E C T ION S

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU 31

B E N T L EY U N B O U N D

How the Bentley archived the pandemic in real time. By Lara Zielin

ZOOM MEETING SCREENSHOTS. Journal entries. Course assignments. Social distancing signage. Tributes to essential workers. These are just a few of the materials that the Bentley Historical Library collected from the U-M community to help document the COVID-19 pandemic. The library launched its COVID-19 collecting efforts in April 2020 to document the varied experiences of students, staff, and faculty during the beginning of the pandemic. “When future students, scholars, and researchers want to understand what it was like at the University of Michigan during the pandemic, the materials preserved by the Bentley will provide a first-person account,” says Project Archivist Caitlin Moriarty, who was part of the team spearheading the project. Bentley archivists created an online form to accept submissions, and responses came in from across campus. Some materials showed how coursework changed when faculty and students had to complete projects and research remotely, such as the films submitted by Senior Lecturer Terri Sarris. The students in Sarris’s Introduction to ProA sign near duction and Wolverine TV Michigan Stadium (WOLV-TV) classes switched in March 2020 their final projects to docuadvises sheltering in place to stop the ment an aspect of the COVID spread of COVID-19. experience.

32 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

“The projects capture the upheaval, confusion, isolation, inability to focus, absence, uncertainty, and even some hope, that students were feeling in this unprecedented time,” Sarris says. Other materials came in as a result of Bentley outreach, including the newsletter of Environmental Services at Michigan Medicine, who clean and maintain the hospital. “This is especially true at this important moment when they are on the frontlines as essential workers,” Moriarty says. All submissions to the project were digital. The process of asking multiple people to contribute to a specific theme represents an unusual kind of collecting process for the Bentley. Traditionally, most people or individuals who donate to archives submit a collection of their papers or records. In this case, “people who had just one thing, such as one photo, could submit it to be part of a community-created collection,” explains Moriarty. Moriarty says that, if successful, this could be a model that the Bentley applies to collecting in other areas. About 150 submissions to the online form were received, and the next step is to process the materials and make them available online. This material represents a small portion of what the Bentley will ultimately collect on COVID-19. More material will be acquired from U-M departments and units, from individual donors, and from Michigan organizations. “One hundred years from now, it will be interesting to see what survives,” Moriarty says. “When you’re living it, it feels like everything is important, but things will filter out over time. This will become like an archival sample of that moment, sort of a time capsule in a way.”

QUARANTINE BY THE NUMBERS 3,530

files produced from 39 digitization requests

345

researcher email requests received and responded to

321

finding aids created 191 GB of digital material processed

52

social media posts generated

42

new websites archived 23 GB of digital material accessioned

4

issues of the new Bentley e-newsletter sent

3

virtual events hosted (and more to come)

BRIAN WILLIAMS

Collecting During COVID-19

COLLECTIONS, the magazine of the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, is published twice each year. Terrence J. McDonald Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Professor of History and Director Nancy Bartlett Associate Director Lara Zielin Editorial Director Robert Havey Communications Specialist Patricia Claydon, Ballistic Creative Art Direction/Design Copyright ©2021 Regents of the University of Michigan ARTICLES MAY BE REPRINTED BY OBTAINING PERMISSION FROM: Editor, Bentley Historical Library 1150 Beal Avenue Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2113 PLEASE DIRECT EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE TO: laram@umich.edu 734-936-1342 Regents of the University of Michigan Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor Sarah Hubbard, Okemos Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor Mark S. Schlissel, ex officio The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office for Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-6471388, institutional.equity@umich.edu. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.

Meet Jim Richardson HELP PROTECT HISTORY FOR THE FUTURE.

Jim Richardson came to the Bentley as part of a rare set of photographs depicting African Americans serving in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) during the Great Depression. But precious little information was available about him, or any of the men in the images. The Bentley digitized the CCC photos, then started a crowd-sourcing campaign to uncover identifying information. Jim’s full name, as well as his background as a hard-working farmer and community member, was brought to light.

Your support can help bring Jim’s story, and others like it, into the 21st century. PLEASE USE THE ENCLOSED ENVELOPE OR GIVE ONLINE TO HELP US DIGITIZE OUR COLLECTIONS.

bentley.umich.edu/giving 734-764-3482

A B O U T T H E B E N T L EY

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN 1150 BEAL AVENUE ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48109-2113

Where Michigan’s History Lives The Bentley Historical Library is now open by appointment only for U-M faculty, students, and staff. The library’s Reference team will continue to receive and respond to remote requests from researchers who are not affiliated with the University, however, the ability to check physical collections remains limited and it may take staff some time to respond. MAKE A RESEARCH REQUEST Bentley.ref@umich.edu EXPLORE COLLECTIONS AND FINDING AIDS ONLINE bentley.umich.edu FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL facebook.com/bentleyhistoricallibrary @umichbentley @umichbentley MAKE A GIFT bentley.umich.edu/giving 734-764-3482

ARCHIVING DURING A PANDEMIC (Above) The virus that causes COVID-19, pictured here, closed the Bentley to the public by order of the governor from March to September 2020. But that didn’t stop archivists and staff from getting creative about collecting materials and promoting Michigan history. Read about how the Bentley documented COVID-19 on campus and much more on page 32.