COLLECTIONS

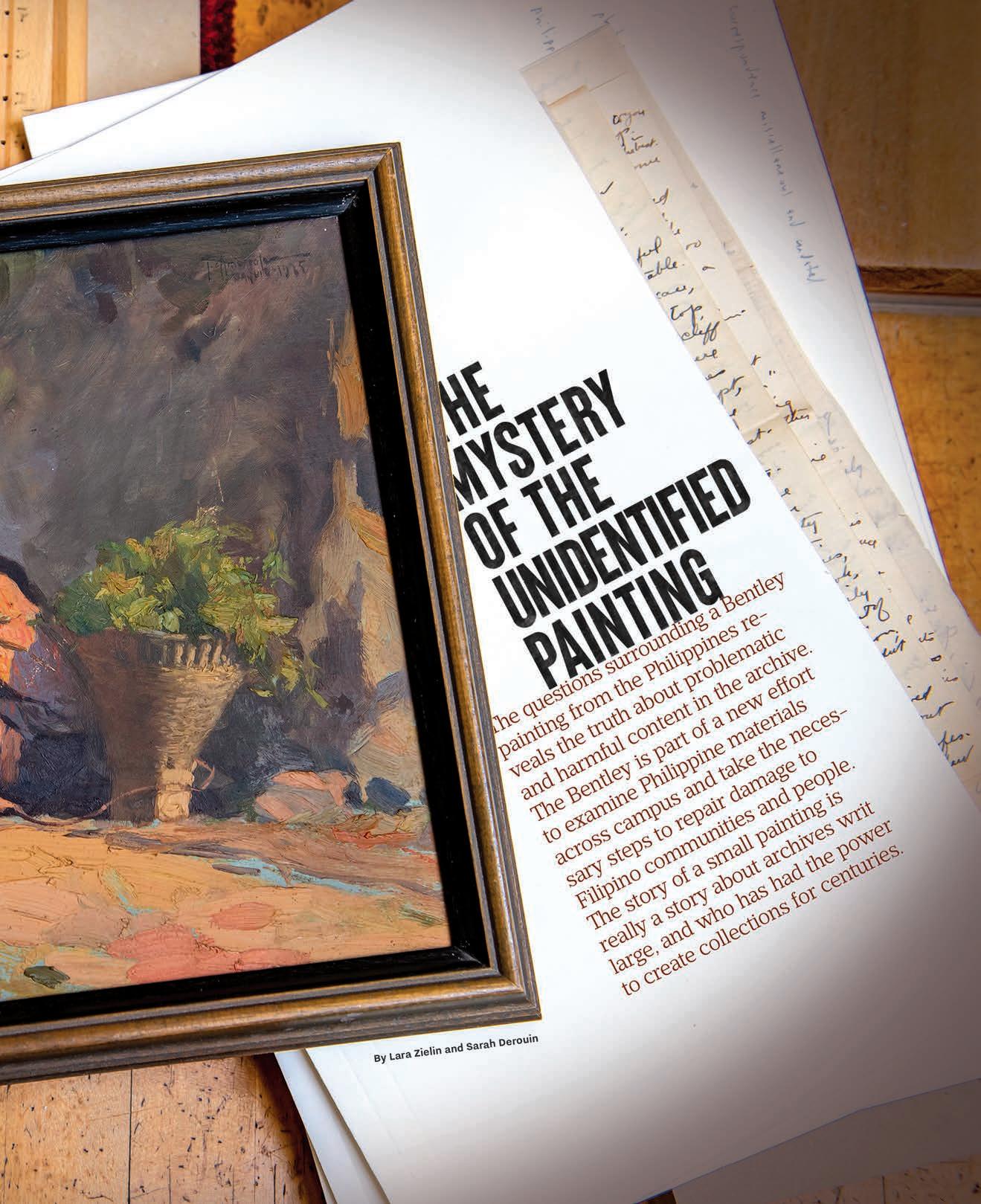

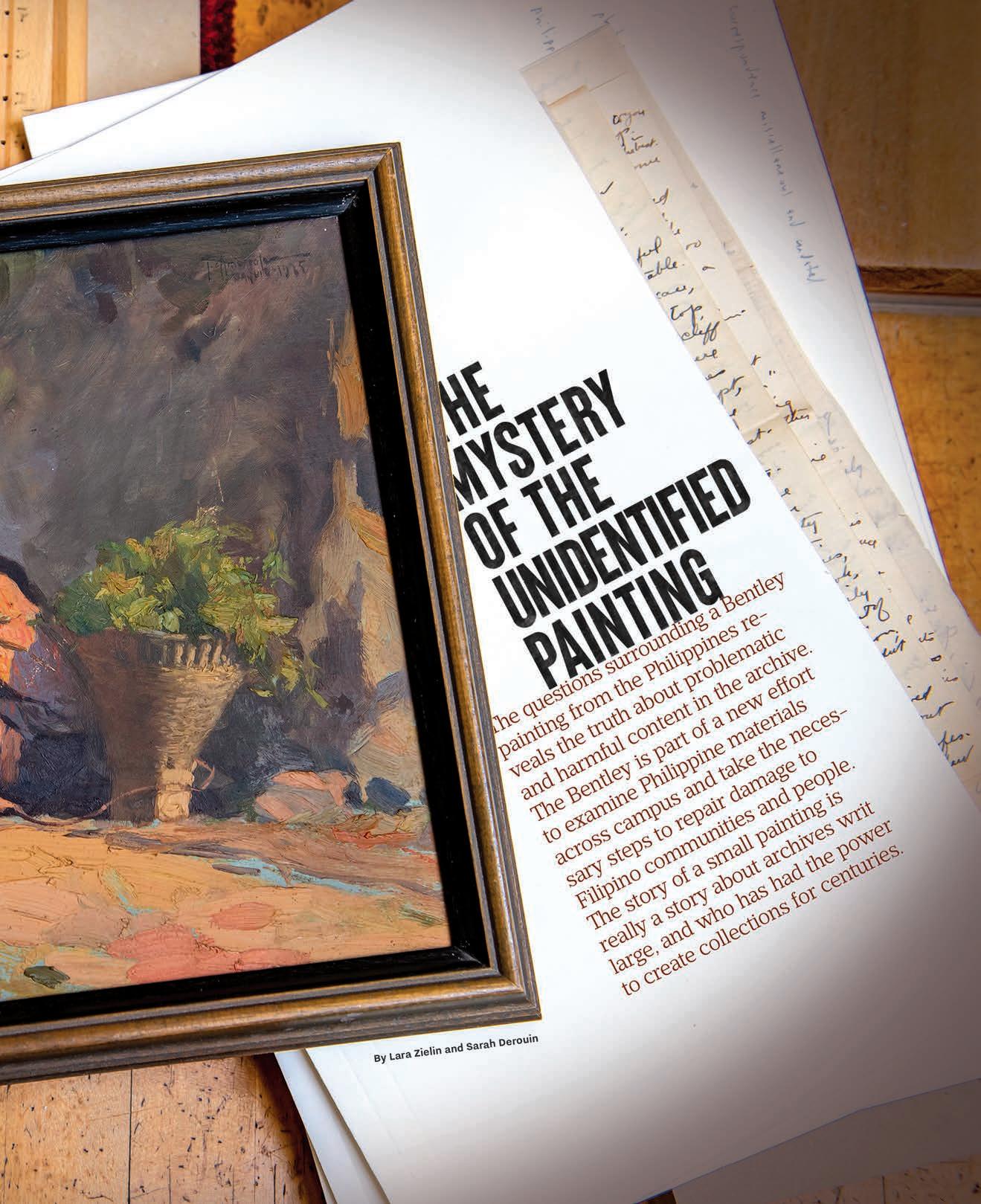

THE MYSTERY OF THE UNIDENTIFIED PAINTING

Is this the painting of a renowned Philippine artist? Why does the Bentley have it in the first place? The painting is part of myriad Philippine materials at the library—many of which contain harmful and racist content. One small painting frames critical questions.

A PUBLICATION OF THE BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY

FALL 2022

The Mystery of the Unidentified Painting

10 Love Is a Battlefield

18 Arab Liberation Radio

FALL 2022 contents EDITOR’S NOTES 1 Changing Interpretations ABRIDGED 2 Select Bentley Bites IN THE STACKS 24 “Problem Pregnancies” and Historical Access 26 Between the Stars and the Sea PROFILES 28 A Matter of Pride BENTLEY UNBOUND 30 Big Fish 31 Beam Me Up, Bentley! 4

Who painted it? Why does the Bentley have it? One small painting frames complex issues of who, historically, has created collections in the archive, and what happens when those collections contain harm ful and problematic content.

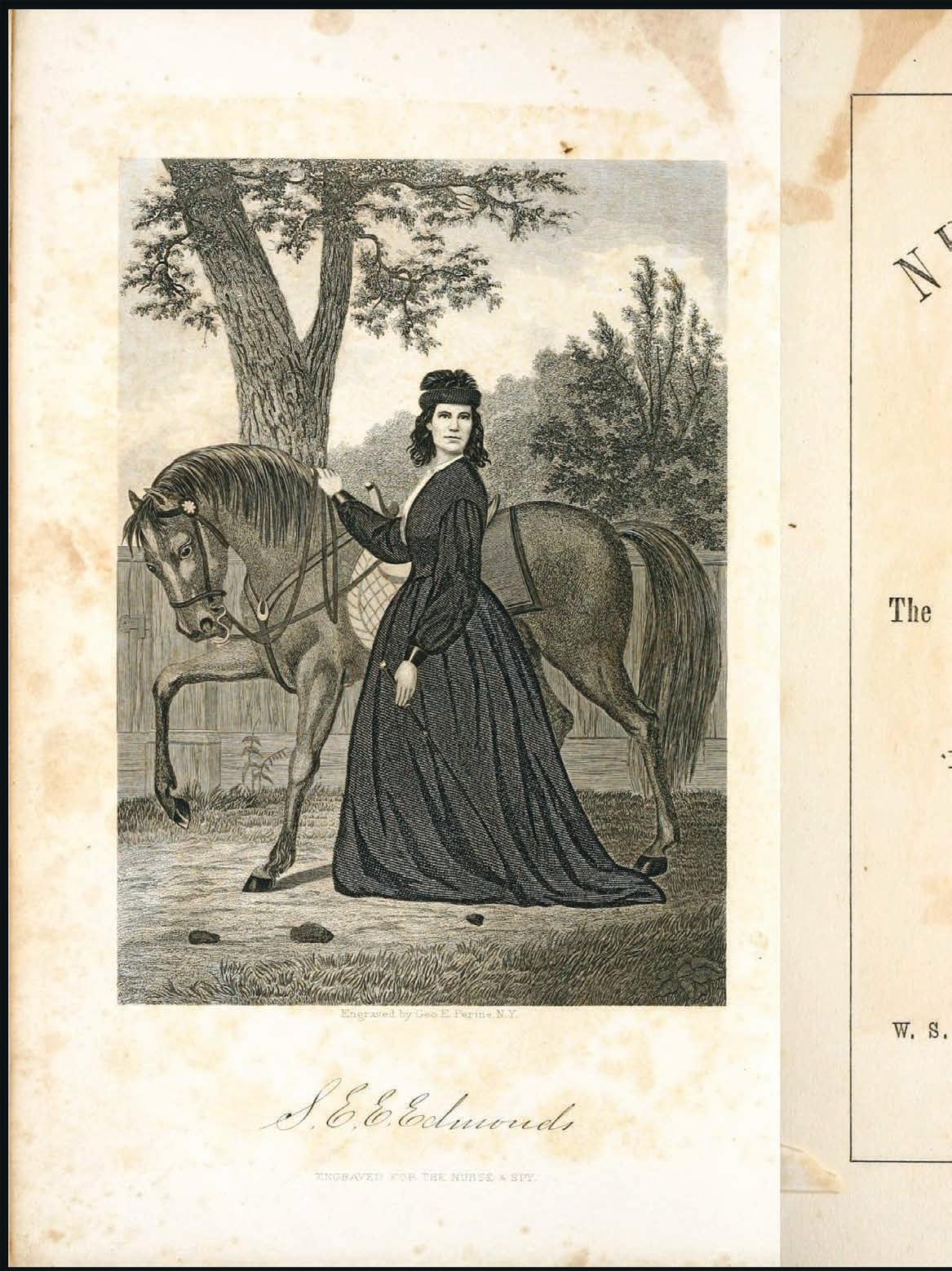

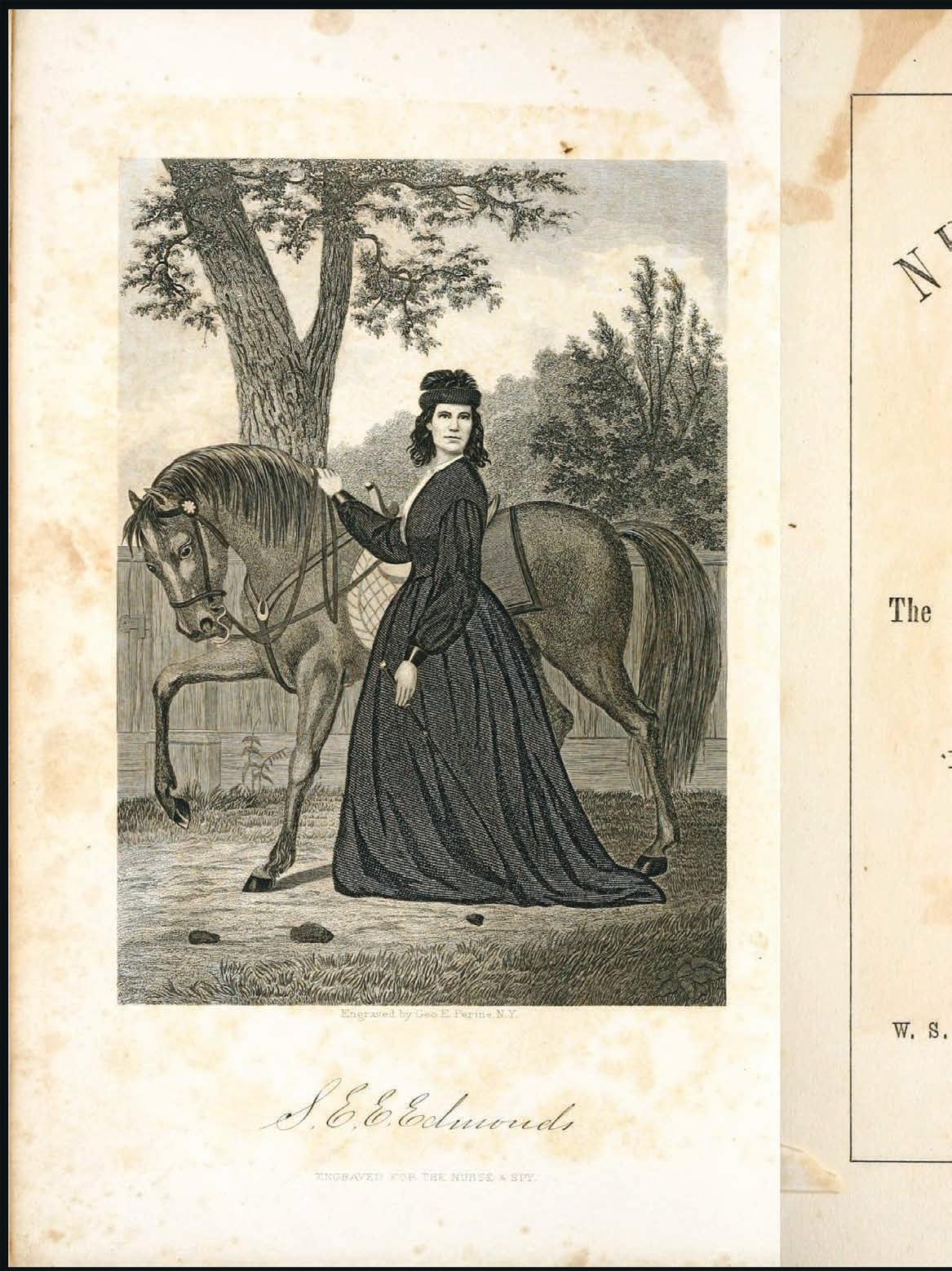

Sarah Emma Edmonds escaped into the United States from Canada, fleeing an arranged marriage. In the U.S., she disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the Civil War. Things got more complicated when she fell in love with a fellow soldier.

The archives of Radio Tahrir feature 25 years of Arab and Arab Ameri can voices on a groundbreaking program hosted by Dr. B. Nimri Aziz. It was an essential outlet for the voices of Arab people living in the United States and abroad.

KERSTIN

Changing Interpretations

MONTHS AGO, AS COLLEAGUES AND I were planning this issue, I was excited to research a story about a successful author from the 1920s with deep Michigan ties. However, as I dove into his collection, I became increasingly uncomfortable.

For example, in several archived docu ments, the author maintained he grad uated from the University of Michigan, even though he never did. He boasted that he held the record for a bicycle mileage record, which was also false.

(Top) The 2022 Kalayaan gather ing, the largest Filipino American event in Michigan, included members of a U-M initiative to decolonize Philippine collections across campus.

(Left) Two un named Filipino girls posing in ferns, possibly unwillingly, illustrate the need for reparative scholarship.

His biogra phy hinted that, even though he wrote about places through first-per son accounts as if he’d been there, he often had never set foot in those loca tions. It’s likely he also fabricated “facts” around one of his most popular magazine articles.

I shelved the story in favor of doing more

research, which is why I’m not naming the author here in these notes. Primary sources like those found at the Bentley and other archives are evidence in the histor ical record—while stories like the kind in this magazine are one way of interpreting that evidence. And interpretation can be a tricky thing.

The challenges of interpretation can be found throughout this issue, including our story about the University of Michigan’s abortion counseling services in the early 1970s, when abortion was illegal in the state before the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision.

Documents show how U-M staffers coun seled women with unwanted pregnan cies by guiding them toward safe, vetted clinics in New York state, where abortion was legal. Archived papers illustrate how lawyers, clergy, and University leadership wrestled with whether this interpretation of the law was best the way to serve women as they navigated a complicated space. (No word on whether U-M will once again offer such counseling services now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned.)

In our features, you’ll find a story about a painting that came to the Bentley in 2013, and which may have been mislabeled

because neither the archive nor the donor knew its cultural context or significance.

The painting is part of a larger discussion about the archive’s numerous collections from the Philippines, many of which con tain harmful and racist material. In the past, collectors of such materials may have been heralded as globe-trotting heroes. But, today, new archival efforts to decolo nize and reexamine these collections (and the people who created them) are changing the lens on this kind of interpretation.

The Bentley’s former director, Terry McDonald, always said that the interpre tation of history—of what’s in the archive and beyond—changes as a result of the present, not the past. “The interpretation of the past by one generation is replaced by that of another,” he wrote in 2021. “And that could, does, and probably should happen again and again.”

The stories in this magazine about the materials at the Bentley, and our interpre tation of what they might mean, continue to change as well.

Lara Zielin Editorial Director Bentley Historical Library

1

BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

EDITOR’S NOTES

ROBERT

DIAZ AND

BARNDT

abridged

A 1947 letter from Assistant Dean of Women Mary Bromage assuring a concerned parent that there was no truth to the rumor that female students who did not eat bread crusts would not be served toast.

Heavy Medal

Maebelle Mason proudly wears medals she received after rescuing a drowning man on the Detroit River on May 11, 1890. A lighthouse keep er’s daughter, she was just 14 years old at the time. Her picture can be found in the Bentley’s History of the Great Lakes publication.

RUBIES IN SPACE

@ILARIASCAGLIA1:

Enjoying every minute of research @umichBentley and at Special Collections @UMichLibrary! Boundless kindness from everybody, from bus drivers to random students I keep stopping for directions, to most amazing archivists. This kind of stuff restores my hope for humanity.

A “ruby maser” sounds like treasure—though actually, it’s a radio detector. It was created through Project Michigan, U-M’s secret mil itary research program, in 1957. Rubies don’t emit much radio interference, making them useful for catching faint, deep space signals. They’ve even taken readings from Saturn! No classified materials here: the Chi hiro Kikuchi papers are open to the public and have many more details.

2 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

ABRIDGED

“At no time has our office authorized any decision by League House mothers whereby girls who do not eat crusts should not be served toast.”

abridged

294 Number of

students, across 19 classes, who used Bentley resources as part of their curricu lum in a U-M course for the 2022 Winter and Spring/ Summer terms.

A band marched down the Diag for U-M president Marion Bur ton's inauguration in the spring of 1920. On July 14, 2022, U-M announced Santa Ono as the 15th president of the University. He will take office in October 2022, and is making history as the first Asian American President of U-M.

6

Barrier Breaker

ANN ARBOR’S FIRE FIGHTING HISTORY IS LIT

At the turn of the 20th century, fires from oil lamps and wood-burning stoves posed a significant threat to Ann Arbor citizens. The city built Fireman’s Hall in 1882 and hired its first full-time fire chief, Fred Sipley, in 1889. In 1906, when this photo was taken, teams of horses and wagons would rush to the scene of a fire when the alarm sounded. By 1915, the city had retired its horses and had started using motorized trucks.

Number of quarts of “bonded whiskey” seized in a bootlegging raid of U-M’s Fletcher Hall in early November, 1929. Three students were expelled from U-M as a result.

5

Number of days per week the Bentley is open to the public by appointment. We recently added Monday hours into our schedule. We look forward to seeing you!

Caroline Hubbard Kleinstuck was the first woman to earn a Master of Science degree at U-M in 1876. “You can do it. I’ll back you up,” was her motto, accord ing to an article in the 1931 Mich igan Alumnus. An early member of the League of Women Voters, she advocated for education and donated to help found the Michigan League. In her Alum nae Survey response, she remi nisced, “I can never forget what the opening of Michigan Univer sity meant to all women.”

BLOEMFONTEIN, SOUTH AFRICA

MANILA, PHILIPPINES

STAR TREK ENTERPRISE

WASHINGTON CEMETERY, HOUSTON

DAMASCUS, SYRIA

DOUGLAS LAKE, MICHIGAN

NEW YORK STATE Locations visited in this issue of Collections magazine.

3BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

COLLECTIONS ABRIDGED

They conferred among themselves: Could it really be?

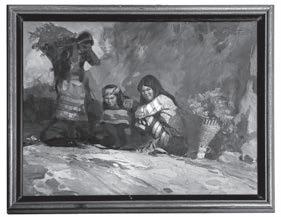

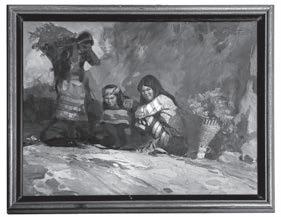

The painting had all the hallmarks of Fer nando Amorsolo—a prolific painter who created an estimated 10,000 works over his lifetime, many depicting Filipino people, landscapes, and culture. An essay for the National Commission for Culture and the Arts called Amorsolo “a master of the Phil ippine landscape.” More colloquially, he is called the Philippine Norman Rockwell.

If the painting was an Amorsolo, it would be significant. Museum-worthy, perhaps, and an important work by the artist, likely early in his career, that would warrant notice.

The painting lay flat on the table, a small rectangle of canvas with a dull brown frame, surrounded by archival boxes materials.and

One by one, the Filipino artists and the archival team working alongside them in the library found them selves examining the artwork. They studied it. Held it up. Took in the painting’s three women dressed in bright reds, oranges, and yellows. Two of the women are depicted squatting against a small embankment, a basket of harvested greens nearby, staring out of the frame with a mix of puzzlement and possibly annoyance.

Yet, in the catalog record, the paint ing’s artist is listed as “T. Amurgot (?)” The question mark suggests the signature was unrecognizable to the catalog creator.

It took Filipino artists visiting the Bentley in person to flag the name—and to note the painting’s potential significance.

Now, an investigation is underway to determine if the paint ing really is an Amorsolo. However, the question of authenticity is almost secondary to why the Bentley came to have a Philip pine painting to begin with (Amorsolo or not)—or a plethora of Philippine collections, many of which contain harmful and racist material.

To understand that—and why the Filipino artists were at the Bentley that day studying Philippine-centric collections in the first place—history has to be unfurled back to the 1870s, when a U-M alum and naturalist named Joseph Beal Steere decided to go abroad to collect specimens.

U.S. IMPERIALISM AND U-M COLLECTIONS

Steere was ready to collect artifacts from the other side of the world, but it was an expensive undertaking and he needed help.

His uncle, wealthy businessman, newspaper publisher, and U-M alum Rice Aner Beal, agreed to finance an expe dition in exchange for letters chronicling the tour that Beal could publish in his paper, the Ann Arbor Courier.

With his funding secure, Steere mapped out an ambitious itinerary. Between 1870 and 1875, he traveled to South Amer ica, the Philippines, Taiwan, and China, with stops along the way. Steere’s collections grew, and by the time he returned to U-M, he had amassed some 60,000 specimens of plants, ani mals, and insects, and more than 800 cultural objects. The haul became the foundation of the first U-M museum building

6 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

(PREVIOUS PAGE) LON HORWEDEL

project and landed Steere a position as a zoology professor at the University.

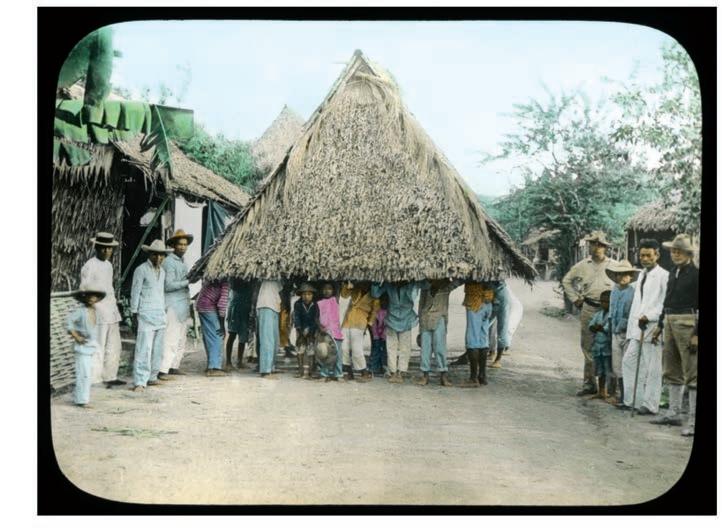

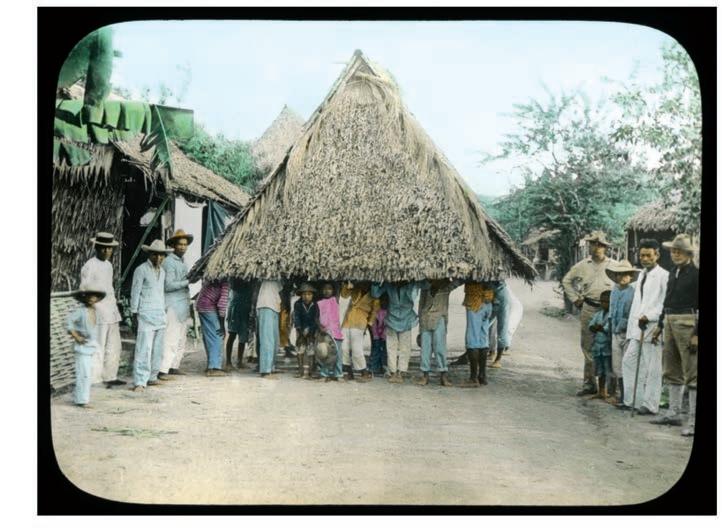

By the turn of the century, the Philippines was in political tur moil. The country had been a colony of Spain before it became a U.S. territory in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War. As part of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, Spain sold the Philippines, Cuba, the Mariana Islands, and Puerto Rico to the United States for $20 million.

The Philippines wouldn’t be fully independent of the United States until 1946.

In the meantime, enter American imperialists and colonizers— and deep Michigan ties.

Some came to the Philippines as government appointees, such as Dean Conant Worcester, a one-time student of Steere at U-M. Worcester was appointed Secretary of the Interior of the Philip pine Islands by President McKinley and was also an avid photog rapher. He documented Indigenous communities and Filipinos, and his photographic collection and archive are spread across the U-M Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, the Bentley, and the University Library’s Special Collections Research Center.

Others came as missionaries and doctors—or both, as in the case of Grace and James Miller. Grace was a teacher at the Brent School in the Philippines during the 1920s, and her brother, Dr. James M. Miller, was a U.S. Army physician at the Sternburg Gen eral Hospital in Manila during the same period.

Their collection includes letters, diaries, photographs of hospi tal staff, as well as images of Filipino people and scenery.

It also includes the mysterious “T. Amurgot” painting.

It’s not clear from the catalog record or donor file where or how the paint ing came to the Millers. It was donated to the Bentley, along with the rest of the Millers’ papers, in 2008 by Grace’s niece, Jane Miller, who died in 2013.

It’s not clear from the catalog record or donor file where or how the painting came to the Millers. It was donated to the Bentley, along with the rest of the Mill ers’ papers, in 2008 by Grace’s niece, Jane Miller, who died in 2013.

But what is clear is that U-M has thousands of arti facts from the Philippines spread throughout multi ple campus locations—one of the largest collections of historical Filipino artifacts outside of the archipel ago nation.

“A community from the Philippines has never said, ‘Here, take our materials,’” says Nancy Bartlett, associ ate director of the Bentley.

“It’s outrageous when you think about it,” says Deir dre de la Cruz, associate professor of history in U-M’s College of Literature, Science, and Art.

“What are these Philippine artifacts and photo graphs and archival materials doing here, halfway around the world, in the middle of the United States? Do Filipinos even know they exist? There’s not enough recognition of how complicit [U-M] was in American imperialism, and not enough knowledge and educa tion about that history.”

RECONNECT / RECOLLECT

Ricky Punzalan, associate professor of information and a Filipino scholar, wanted to upend the curation confusion and repair the damaging colonial history of the Philippine collections. He teamed up with de la Cruz, and together they are co-leading the project ReConnect/ReCollect: Reparative Connections to Philip pine Collections at the University of Michigan.

The goal of the ReConnect/ReCollect project is to look at the collections with fresh eyes, repair harmful historical descriptions, and construct new models for how to best engage community members and schol ars with the plethora of Filipino history stored at U-M. Punzalan and de la Cruz assembled a team of faculty, students, librarians, archivists, and community mem bers to take on this critical reparation work.

The project also works in partnership with col lections faculty and managers beyond the Bentley, including U-M Library’s Special Collections Research Center and the Museum of Anthropological Archae ology. Together, they are creating recommendations for representing Philippine collections held by vari ous campus units.

7BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

(Clockwise from top left)

The ReConnect/ReCollect artists in residence view materials at the Clem ents Library.

A Philippine ceremony labeled only “wedding dance.”

Janna Añonuevo (left) and Ricky Punzalan (right) examine Philip pine materials at the U-M Library.

A Philippine housemoving tradition called Bayanihan.

“

8 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

In the archives, we do research and description, but it doesn’t mean we understand the whole story. This painting shows the value of connect ing with the community, because so often there is knowledge embedded in the culture. The true value of archival objects comes from interaction.”

U-M recognized the importance of this reparative work on the Philippines collection and awarded the project a $500,000 grant toward the pilot program.

“This project is really a first in terms of bringing together curators, librarians, and archivists from across campus to look at collections that are highly distributed,” says Bartlett. “We are having conversations as a team about these import ant collections that we’ve never had before.”

The imperialist origins of the Philippine collections are only one part of its problematic history. The collection is spread out around the campus, housed in various libraries and museums.

Artifacts are separated by campus geography, and also further isolated by spotty, poorly named, and disconnected records—as the “T. Amurgot” painting exemplifies.

“There is, at best, inaccurate information around the descrip tion of the collection, and that’s to put it mildly,” says Punzalan. “Some items have information that is just wrong, racist, or harm ful to Indigenous source communities.”

Repairing the Philippine collections at U-M is crucial not only to the academic community but also to the Filipino community in Michigan and beyond.

“These are hugely important collections at an international level, in terms of the history of imperialism in the Philippines,” Bartlett says. “The University of Michigan is a ‘go-to’ destination for that highly complicated story.”

ARTISTS IN RESIDENCE

As part of ReConnect/ReCollect, three visual artists were chosen for a paid, two-week residency to engage U-M’s Philippine collec tions, exploring themes of archives, material history, decoloniza tion, Filipino identity, and more.

Francis Estrada, Janna Añonuevo Langholz, and Maia Cruz Palileo were the artists chosen out of numerous appli cants, and they were all present that day when the possible Amorsolo painting was identified. In fact, it was because of Palileo, a visual artist, that the painting was among the materials to be explored in the first place. They had requested it from the catalog as part of what they wished to explore at the Bentley during their residency.

“Francis [Estrada] came over and he said, ‘that looks like an Amorsolo,’” explains Cruz Palileo. “He asked if there was a signature and we googled it. It was a match, though of course it could still be a copy. Even so, there was a lot of buzz in the room when it happened. If it’s real, that’s quite a find.”

However, the painting was still part of materials that were challenging for Cruz Palileo and the other artists to view and explore: pictures of Indigenous commu nity members being posed and exploited; sacred cer emonies without context or attribution; letters and diaries labeling Filipinos as savage and uncultured.

“It’s difficult to be entrenched in these materials, to look at history through the lens of colonization and violence,” says Cruz Palileo. “We [the artists] felt like we were collectively grieving. There was grief and anger—and some moments of joy. It was very emo tional and draining.”

Those emotions, Cruz Palileo says, are being poured into the paintings they are in the process of creat ing now. “I’m working it out in the studio. It’s being channeled.”

All while the other painting—the possible Amor solo—is being carefully examined for more clues that could help determine its authenticity.

Documents from the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution may be able to place the Millers and Amorsolo at a 1925 exhibit in New York, confirming their connection. Deeper research into the Miller family may uncover a letter or a photo that could provide context clues. And Punzalan hopes to share high-resolution scans of the painting with cura tors and conservators in the Philippines, who can help determine next steps.

“Whether or not the painting is an Amorsolo, it still speaks to many things that need addressing,” Pun zalan says. “Why we had it, why it was mislabeled, why no one knew about it.

“In the archives, we do research and description, but it doesn’t mean we understand the whole story,” he adds. “This painting shows the value of connecting with the community, because so often there is knowl edge embedded in the culture. The true value of archi val objects comes from interaction.”

Portions of this story were used with permission from the School of Information and its coverage of the ReConnect/ReCollect project in May 2022.

9BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) JEFFREY SMITH; GRACE H. AND JAMES M. MILLER PAPERS; JEFFREY SMITH; HS20035

� OVE IS �

SARAH EMMA EDMONDS

DRESSED AS A MAN ON THE BATTLEFIELD DURING THE CIVIL WAR AND RISKED BLOWING HER COVER WHEN SHE CONFESSED HER LOVE FOR A FELLOW SOLDIER. THIS STRANGE TALE OF UNREQUITED LOVE IS DOCUMENTED IN ARCHIVED JOURNALS AT THE BENTLEY AND REVEALS HOW ONE WOMAN’S WAR-TIME SECRET FINALLY CAME TO LIGHT.

By Jenn McKee

By Jenn McKee

� ATTLE � IELD

As a teen, Edmonson’s abusive father arranged for her to be mar ried to a significantly older man. To escape the unwanted mar riage, she fled to another town, where she trained and worked in a millinery and altered her name to Edmonds.

When her father picked up her trail, Edmonds knew she needed to deepen her disguise. That’s when she donned men’s clothes and crossed the border into the United States as someone else entirely: Franklin Thompson.

As Frank Thompson, she traveled to Connecticut first, to meet with a book publisher, and sold Bibles, eventually making a home for herself in Flint, Michigan.

In 1861, at age 19, Edmonds, driven by a patriotism for her new home country, enlisted as a soldier in the Civil War. But she also soon fell in love with a fellow soldier—a strange and romantic epi sode that’s documented in papers at the Bentley, and that reveals the startling secret Sarah couldn’t keep.

�RIENDSHIP IN EXCHANGE FOR FRIENDSHIp

Edmonds first attempts to enlist were thwarted by her small size—the Army’s height requirement was 5'8"—but she eventually began her Army career as a nurse. She landed at a field hospital in Washington, D.C., where she met a private named Jerome Robbins, who’d come to visit a sick friend before getting a hospi tal position of his own.

The Bentley has nine of Robbins’ journals from this period of his life, as well as two letters Edmonds wrote to him.

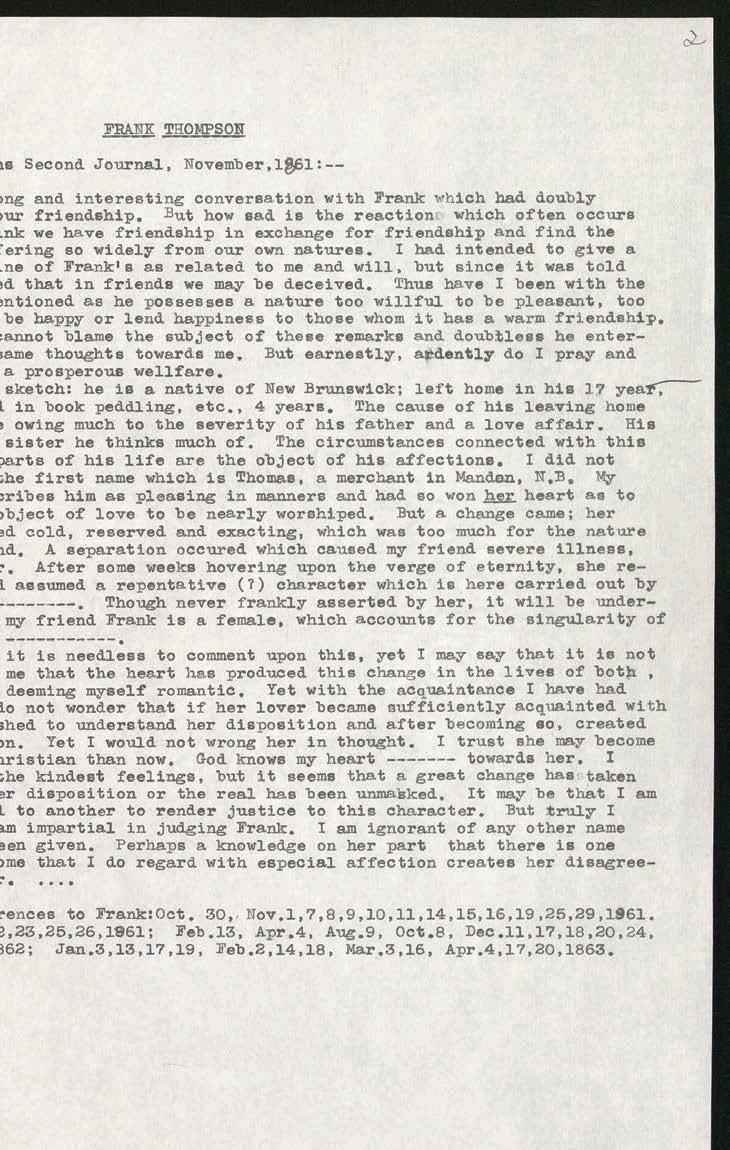

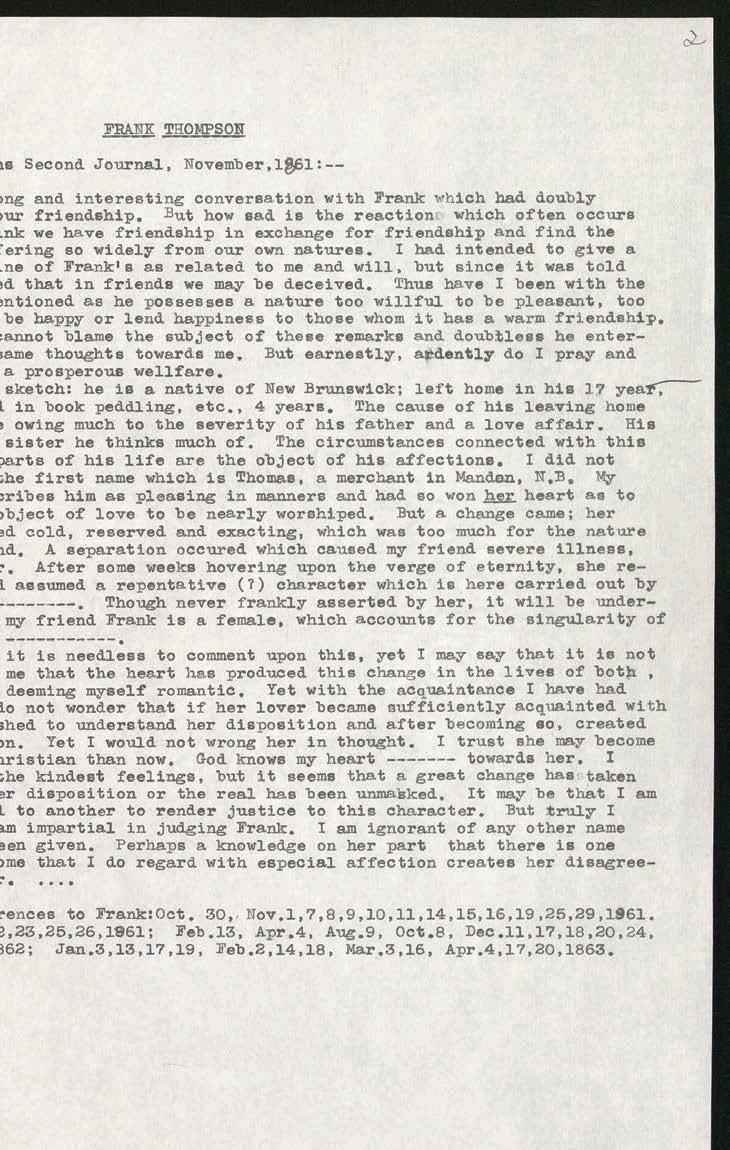

The first mention of Edmonds, in the guise of Frank, is noted on October 30, 1861, when Robbins wrote, “I had a very pleasant conversation with Frank Thomp son on the subject of religion.”

Indeed, both Edmonds and Robbins were guided by their faith, to such an extent that they attended prayer meetings together and often went on long walks to share their thoughts on the subject.

Robbins, though grateful for his newfound friend, began to wonder if something was amiss.

On November 11, 1861, he wrote:

“One consolation I have which I receive as a blessing: the society of a friend so pleasant as Frank I hail with joy. Though foolish though it may seem, a mystery appears to be connected with him which it is impossible for me to fathom, yet these may be false worries.”

They were not false worries, of course. As Rob bins confessed his deep affections for a young woman back home in Michigan named Anna Corey, Edmonds felt compelled to reveal her true identity to Robbins.

The heading over Robbins’ journal entry for Novem ber 16, 1861 reads, “Please allow these leaves to be closed until the author’s permission is given for them opening,” underscoring the need for privacy in regard to the sensitive account.

“How sad is the reaction which often occurs when we think we have friendship in exchange for friend ship and find the friend differing so widely from our own natures,” Robbins writes.

He reflects that “in friends we may be deceived,” and eventually writes plainly that although “never frankly asserted by her, it will be understood that my friend Frank is a female.”

ENTRENCHED IN SECRECY

Robbins could have been shocked enough to turn Edmonds in or tell others in the military camp. How ever, he keeps Edmonds’ secret, continues to call her Frank, and continues to use male pronouns.

12 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

Canada, Sarah Edmonson discovered the novel Fanny Campbell, The Female Pirate Captain: A Tale of the Revolution! and began to imagine a more unconventional, adventurous life for herself. She didn’t have to wait long to get started.

COLLECTIONS (THIS PAGE AND PREVIOUS SPREAD) NURSE AND SPY IN THE UNION ARM Y, 1865

AND SPY IN THE UNION ARM Y, 1865

NURSE

One possible explanation for this complicity is that war had blurred gender roles and women were already on the battlefield anyway—caring for the wounded, sewing uniforms, distributing supplies, and more. According to the National Archives, an estimated 250 women fought as soldiers in the Con federate army alone.

“I am convinced that a larger number of women disguised themselves and enlisted in the service, for one cause or other, than was dreamed of,” wrote Mary Livermore in 1888. Livermore had worked for the U.S. Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, providing medical care and other services to Union soldiers. “Entrenched in secrecy, and regarded as men, they were sometimes revealed as women, by accident or casualty. Some startling histories of these military women were current in the gossip of army life.”

Edmonds’ romantic feelings go unrequited at this vulnerable crossroads and, as a result, Robbins notes that her disposition turns disagreeable. He suspects her resentment is a result of his feelings toward Anna Corey back in Michigan:

“I entertain the kindest feelings [toward Edmonds], but it seems that a great change has taken place in her disposition or the real has been unmasked. . P erhaps a knowledge on her part that there is one Michigan home that I do regard with especial affection creates her dis agreeable manner.”

Robbins comments on Edmonds appearing depressed and distant at times. She also seems to forge new relationships with others in camp. In December 1862, Robbins writes in his journal regard ing Edmonds’ close friendship with a married soldier named James Reid:

“Have not had a very long chat with Frank, and I feel quite lonely without him. But I suppose he enjoys his tent mate. . . . Reid seems a fine fellow and is very fond of Frank.”

In other ways, the pair continued to cultivate the friendship as if little to nothing had changed.

For example, when Robbins was away from camp for an extended period, Edmonds left a note in his journal joking that she’d read it “for spite” and “carried away some of [his] choice magazines.”

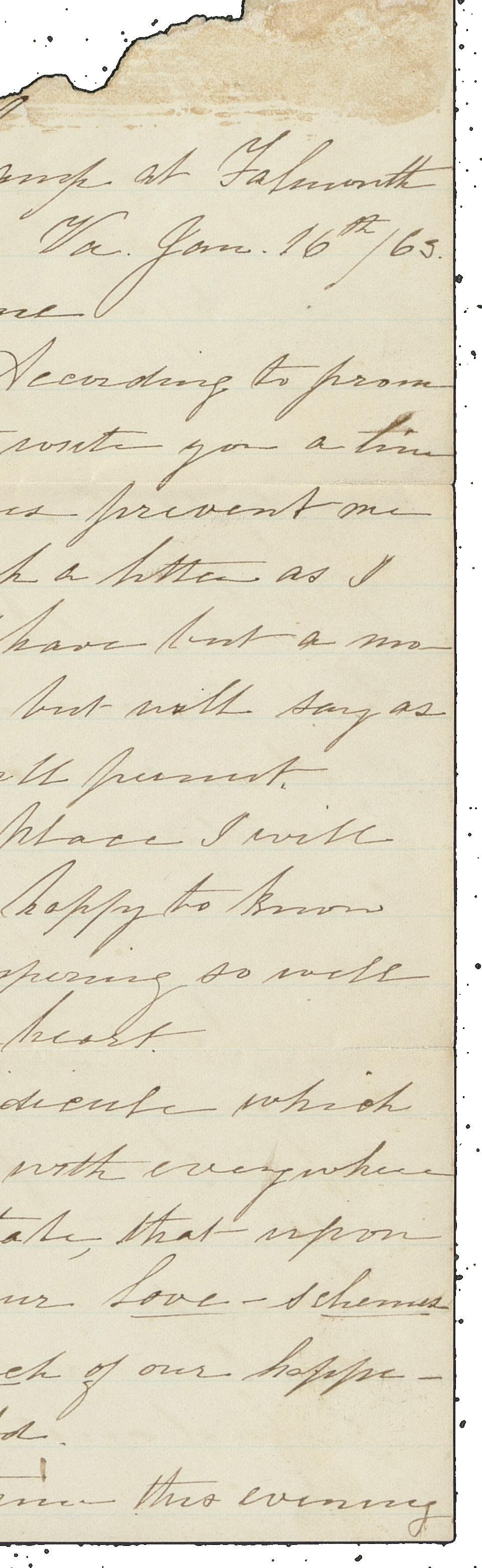

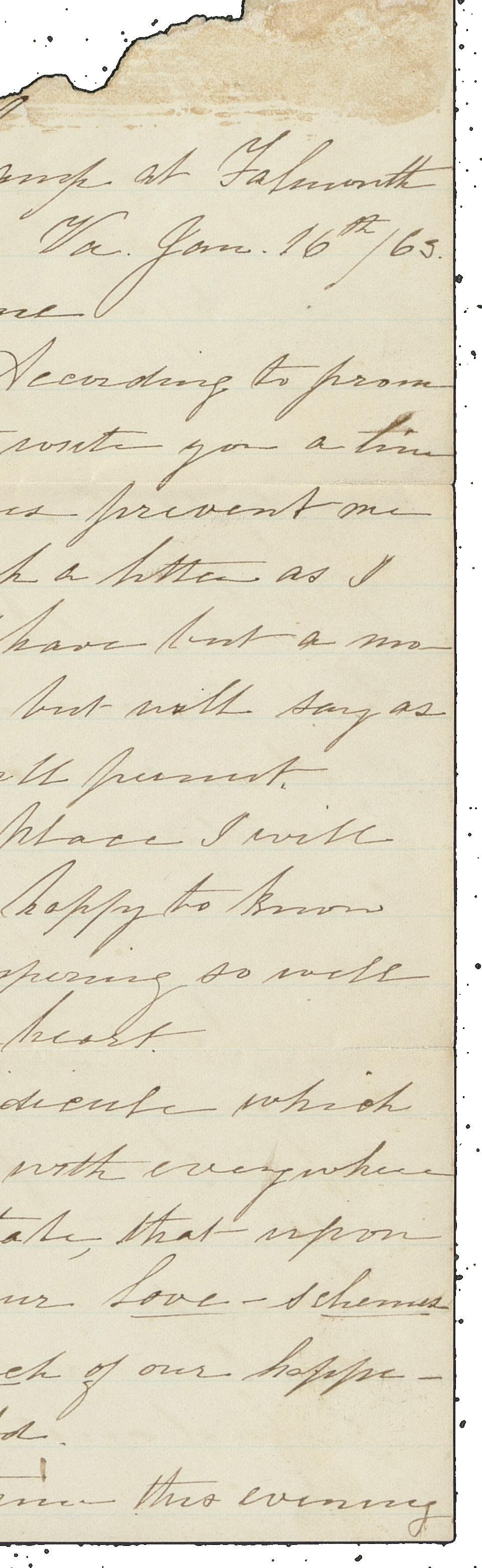

A January 16, 1863 letter from her to Robbins, openly signed as “Emma,” finally offers some emotional candor in her own voice, reading:

FROM DESERTION TO PENSION

Soon thereafter, when Edmonds suffered worsening malaria symptoms, she abandoned her post to seek out medical treat ment in Ohio in April 1863. Though she’d hoped to return to the Army once she was well, posters labeling her a deserter had cir culated, so that option vanished, and she began a new life as a woman again.

Robbins had initially thought some logistic mishap befell Edmonds, but after a few more days of absence, he wrote: “I have learned another lesson in the great book of human nature. Frank has deserted, for which I do not blame him. His was a strange history. He prepared me for his departure in part. Yet I did not think it would be so premature. Yet he did not prepare me for his ingratitude and rotten disregard for the finer sensibilities of others.”

15BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

“I am happy to know that you are prospering so well in matters of the heart. In spite of the ridicule which sentiment meets with everywhere, I am free to state that upon the success of our love-schemes depends very much of our happiness in this world. . . . Dear Jerome, I am in earnest in my congratulations and daily realize that had I met you some years ago, I might have been much happier now. . . . I do not love you less because you love another, but rather more, for your nobleness of character displayed in your love for her.”

(Left to right)

Jerome Robbins circa 1861. A letter to Rob bins from Sarah Emma Edmonds after she’d left her military post due to illness. Transcription of Robbins’ diary entry where he details “Frank Thompson’s” confession of being Edmonds.

16 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

Presumably unaware of Robbins’ anger, Edmonds wrote a letter on May 10, 1863 that reads:

Robbins’ military career continued after Edmonds left camp. He mustered on January 1, 1864, at Blain’s Cross, Tennessee, and was honorably discharged on July 28, 1865.

In the end, Robbins returned to Michigan, but his romance with Anna Corey ended with her marriage to another. In 1867, Robbins graduated from the University of Michigan Medical School and later lived in Boyne Falls, Michigan.

Edmonds, meanwhile, made a splash with her memoir Nurse and Spy in the Union Army in 1865, though several critics have questioned the veracity of some stories told therein. She married a man named Linus Seelye in 1867. They had three children, but all of them died in their youth, and the couple adopted two sons.

In 1876, Edmonds attended a military reunion and was welcomed and cheered by her former colleagues. She did, in fact, have friends besides Robbins in camp, and in the end, they not only helped her get the charge of desertion removed from her record, but also signed affidavits to petition for her to receive a military pension.

It took nearly a decade and an Act of Congress, but Edmonds was eventually cleared and awarded a pension; plus, in 1897, she was admitted into the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War Union Army veterans’ organization.

Edmonds died at age 56 on September 5, 1898, at her home in La Porte, Texas, from lingering malaria complications. She was ini tially buried quietly in a local cemetery but was reburied, in 1901, with full military honors at Washington Cemetery in Houston. In 1992, she was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.

17BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

“I dare not write you the particulars of anything now until I hear from you and know where you are, for fear it might fall into other hands. . . . Oh, Jerome, I do miss you so much. There is no person living whose presence would be so agreeable to me this afternoon as yours. . . . Be careful when you write lest it should get mislaid. Reid seems to think that you are the only friend I have in camp. It may be so, but had hoped that I had one or two more at least.”

(LEFT) HS1121; (MIDDLE AND RIGHT) JEROME J. ROBBINS PAPERS

FOR25YEARS,RADIOTAHRIRAIREDINTERVIEWSWITHWRITERS,MUSICIANS, ACADEMICS,AND OTHERS—ALLARABORARAB-AMERICAN—ANDBECAMEAVITALRESOURCEFORLISTENERSINTHENEWYORKREGION.WITH ARCHIVES HOUSED ATTHEBENTLEY,THESEINTERVIEWS CANNOWBEHEARD AROUND THEWORLD. arabLIBERATION radio byKatieVloet

These are some of the sounds of a quar ter-century of audio from Radio Tahrir. It started like this, on June 13, 1989: “We’ll begin this afternoon’s program with an interview, which I recorded three months ago in Damascus, Syria, with Ghaleb Halasa, an Arabic novelist and literary critic,” Dr. B. Nimri Aziz intoned on the initial program aired through Radio Tahrir.

With that, she established the framework for a project designed to articulate lesser-known but richer sounds and images of the Arab and Arab American worlds.

Radio Tahrir, which aired on the Pacifica Foundation-owned WBAI sta tion in New York City, would grow to become an essential outlet for the voices of Arab people living in the United States and abroad.

“I looked around to see what was being pub lished and broadcast about our people in the United States. There was nothing on TV. Radio productions were either political analysis or oriental music,” says Dr. Aziz, Radio Tahrir’s originator, host, and producer.

She saw a clear need for a different point of view. “I’m an anthropologist. I understood the diversity of our culture and how politics can subsume everything; as a result, there’s a cultural dimension presented about a people,” she says. “I felt I could introduce a positive, deep dimension that was generally unavail able to the public.”

A forever HOME

Sally Howell was aware of Radio Tahrir as a significant forum for Arab intellectuals, as well as Arab American artists. A U-M fac ulty member, she was also aware of the skill with which the Bent ley Historical Library’s archivists handled donated material, and she believed it would be the perfect home for the program’s recordings.

“I was very eager for us to bring it to Michigan. We have these conglomerations of scholars. We have one of the oldest and stron gest Middle East-focused programs here, with language, and Islamic studies, and so much more,” says Howell, associate profes sor of history and director of the Center for Arab American Studies at the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

U-M’s main campus includes a Middle East Studies Depart ment, an Arab language field of study, and an active Arab Student Association. The Department of American Culture offers many

20 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

POETS recite THEIR VERSE OVER THE staccato OF IRAQI DRUM ENSEMBLES ANDthe strummed STRINGS OF ANoud, the ArabLUTE. AUTHORS LIFT THEIR characters off THE PAGE. FILMMAKERS DISCUSSlove stories. AND VOICES THAT AREN’T HEARDanywhere elseARE GIVEN A PLATFORM.

courses in Arab and Muslim American Studies, including those that focus on art, culture, activism, literature, cinema, feminism, and more. One class is called “Camels, Kabobs, and Khalil Gibran: Arab American Cultural Studies.”

Given U-M’s rich representation of Arab cultures in and out of the classroom, Howell encouraged Dr. Aziz to donate her 25 years of Radio Tahrir recordings to the Bentley Historical Library.

The collection is now available online through the Bentley’s digital archives. In one show, a mother broadcasts a message to her imprisoned son. On another installment, scholars discuss Huda Sharawi, an early leader of Egypt’s women’s movement. A Kuwaiti printmaker and painter speaks about her art. U.S. bomb ings are discussed from the point of view of people who live in Arab countries.

Literature, sculpture, film—all art forms found a home on Radio Tahrir. “I think this is going to be a great resource for schol ars of Arab American literature in particular, but also people who are interested in those trans-national ties that connect people across hemispheres,” Howell says. Dr. Aziz “is also a skilled inter viewer. Her style is so relaxed, and she doesn’t shy away from the hard questions.”

In the beginning, it was challenging to find guests with whom she could conduct engaging interviews or ask hard questions, Dr. Aziz recalls. “One had to dig,” she says. The reputation of Radio

THEREPUTATIONTAHRIR—AOFRADIO WORDGREW“LIBERATION”—THATMEANS EARLYINTHOSE YEARS,GUESTSPOTENTIALANDSOON WEREPARTEAGERTOBE OFIT.WHATAZIZBECAME THEPOETDESCRIBESNAOMISHIHABNYE AS“THEHUMANSWITCHBOARD AMONG POETS.”

Tahrir—a word that means “liberation”— grew in those early years, and soon poten tial guests were eager to be part of it. Aziz became what the poet Naomi Shihab Nye describes as “the human switchboard among poets.”

“After maybe three years of broadcast ing, other Arabs heard us and were excited to be interviewed,” Dr. Aziz says. “They wanted to talk about something other than political crises.”

BY, AND FOR, anArab American AUDIENCE

Many of the guests on the show were Arab or Arab American though, gradu ally, as the program developed, it attracted Muslim Arabs as well as Muslims who were not Arab. Many had connections to U-M, including poet Lawrence Joseph (B.A. ’70, J.D. ’75) and poet Khaled Mattawa, now a professor of English Language and Litera ture at U-M. Dr. Aziz interviewed guests in the United States and during her jour nalistic assignments in the Middle East.

ONAIR

COLLECTIONS

21BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

Dr. Aziz thought it was important that the production staff who worked on Radio Tahrir were of Arab descent. “We Arab Americans had been largely dependent on non-Arab producers. I insisted we be an Arab production center,” Dr. Aziz says.

“We are, after all, the best authorities concerning our own culture and lives.”

Her colleagues at Pacifica’s New York studio were supportive. “Many of them are African Americans, and they understand how a biased media can misrepresent an issue to the public,” Dr. Aziz recalls. “I had that moral support to tell the stories I knew

and that were lacking, or hard to find, in the public sphere.”

These stories included discussions of Arab American comedy festivals, a Ramadan recitation by a schoolgirl, socioeconomic issues in Algeria, reports on a Cairo anti-war conference, and poems by New York schoolchildren about the 1991 Iraq war. The range of topics was rich, and it showed the depth and breadth of the ways Arab Americans lived their lives.

That wide range had an impact on listeners, and on people who worked for the program. Dr. Aziz recalls one volunteer at Radio Tahrir saying what a relief it was to work at a place that told the full story of Arab American lives. It was a safe space, the vol unteer said, where they wouldn’t be asked about their losses or victimization.

“THISSTEREOTYPE—

ARABEQUALSTHEEVIL, GODLESS, CULTURAL OTHER,SOMEONEWHOISDIFFERENT,SOMEONEWHOISA THREATTOPEOPLE—HASCIVILIZEDBEEN(AROUND)FORMORE THANA CENTURY. THEHOLLYWOODARAB,ISTHETVARAB,ISTHECOMIC BOOKARAB,ISTHE VIDEOGAME ARAB. THEREAREALLTOOFEW VOICESWHOSTEPTOTHE PLATFORMAND CONDEMN ITFORBEING RACIST.WE’VE GROWN ACCUSTOMEDTOTHISSYMBOLOGY.”

22 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

ONAIR

Countering “HOLLYWOOD’S VERDICT ON ARABS”

When Hollywood needs villains, people who are Arab or Muslim are often the easy solution, author Jack Shaheen said on one epi sode of Radio Tahrir. Shaheen had examined some 1,000 films and written about his findings in Reel Bad Arabs and Guilty: Hol lywood’s Verdict on Arabs After 9/11

“This stereotype—Arab equals the evil, godless, cultural other, someone who is different, someone who is a threat to civilized people—has been (around) for more than a century,” Shaheen said in the Radio Tahrir interview. Other groups are villainized and stereotyped, he said, “but never for this long.”

“The Hollywood Arab, is the TV Arab, is the comic book Arab, is the video game Arab,” Shaheen said during the interview. “There are all too few voices who step to the platform and condemn it for being racist. We’ve grown accustomed to this symbology.”

Shaheen cited the Arab-Israeli conflict as one reason for this portrayal. Hollywood also became comfortable with “vilifying Muslims,” he said, and has often equated Arab people and Mus lims—even though only about 20 percent of the world’s Muslims live in Arab countries.

Dr. Aziz points out that the Western view of the Arab world grew “overwhelmingly negative” after the 1979 revolution in Iran that overthrew the monarchy and established the Islamic Republic. Following September 11, 2001, she says, “we faced a new, more severe era of anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment across the United States.”

Radio Tahrir provided a platform to counter that sentiment and to tell different stories than network news shows were airing at the time. One segment in early 2002, for instance, highlighted the “Post-911 detention of Muslim Americans on minor immigra tion violations.”

“We had to say, ‘wait a minute, there’s another story to tell,’” Dr. Aziz says.

THE LEGACY of Radio TAHRIR

Radio Tahrir was the first radio program in the United States to focus on a wide range of topics pertaining to different Arab and Muslim communities across the world and, as far as Dr. Aziz is aware, it has not been duplicated.

She and her fellow producers are proud of Radio Tahrir’s “contribution to Amer ican history, spoken by us—Arab Amer icans—in our own words. . . . These productions also represent a positive, cre ative tie between Arabs in the U.S. and Arabs abroad.”

As the co-founder and former executive director of RAWI (Radius of Arab American Writers Inc.), Dr. Aziz has expanded her com mitment to the community by promoting Arab writers articulating Arab experiences and perspectives through their memoirs, novels, and poetry. “These talented writers needed each other too,” she says.

Another part of Radio Tahrir’s legacy is the success of people who worked on the program. One of those is Tamara Issak, Ph.D., who was a contributing producer and host. Now an assistant professor at St. John’s University, her research focuses in part on Islamophobia. She says the Tahrir archive provides critical insights into the social, cultural, and political environment of Arabs and Muslims in the United States and abroad in the past few decades.

Long before the podcasting era, she says, Tahrir was live on the air weekly and some times daily in New York City on the FM dial, giving Arab and Muslim voices a place to frame conversations and discuss their views on contemporary issues.

“It was a forum for our communities and by our communities, and it was ground breaking in that it spoke directly to Arab and Muslim communities and addressed our most pressing issues,” Issak says. “Many world-renowned writers, artists, musicians, and activists were interviewed on Tahrir when they were starting out. Listening to these archival interviews will give research ers and those interested many insights into the early inspiration for their work.”

23BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

“Problem Pregnancies” and Historical Access

Archived papers at the Bentley show how U-M counseled women on their repro ductive options in the early 1970s, prior to Roe v. Wade .

By Jenn McKee

By Jenn McKee

to the campus community that read, in part, “Today’s Supreme Court ruling on the right to an abortion will affect many on our campus and beyond. I strongly support access to abortion services, and I will do everything in my power as president to ensure we continue to provide this critically important care.”

Navigating how to support women in this moment is compli cated, but the University could take a page from its past.

Documents at the Bentley reveal that in 1971, counselors affil iated with U-M’s Religious Affairs Office discussed unwanted pregnancies with women, and if these women wished to explore abortion, they were given information about two vetted clinics in New York, a state where abortion was legal.

Though it may seem surprising that local clergy led the way in providing students with this information, a 1971 letter from coun seling director Leonard Scott to the physician father of two male U-M students elucidates Scott’s journey through this complicated moral terrain.

24 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

“I suppose as long as some of the public wants abortion, and as long as physicians will provide abortion, abortion will remain a reality even for those of us who cannot approve of it on any grounds,” Scott wrote. “But even those who choose abortion nev ertheless are thinking human beings who deserve our profes sional concern.”

Rianna Johnson-Levy, a doctoral student in U-M’s joint pro gram of history and women’s and gender studies, has studied these archived materials extensively, including Scott’s approach to services.

“There are several pamphlets from Scott about how he con ducted problem pregnancy counseling, and it really was coun seling that had no obvious conclusion,” she says. “Everyone was searching in this moment. It was individuals grappling with their own beliefs and trying to figure out what felt right to them.”

Perhaps inevitably, counselors and medical staffers worried about the legal (and insurance-related) ramifications of counsel ing students about abortion. Some were members of the Michigan Committee for Clergy Counseling on Problem Pregnancy, a con sortium of more than 75 Michigan ministers who set up services and even a telephone line to help counsel women with unwanted pregnancies.

“Exactly when this is happening, multiple members of the Michigan Committee for Clergy Counseling on Problem Pregnancy were arrested and raided and wiretapped,” says Johnson-Levy. “Everything U-M did was on the up-and-up, but a lot of these same figures, in their out side-of-Michigan work, it’s clear, were really taking a huge legal risk.”

An archived 1969 letter from Detroit attorney Lloyd A. Semple to a Grosse Pointe clergy member reads that “it is our opinion that it is illegal to counsel abor tions to be performed in Michigan for reasons other than to save the physical life of the woman.” But he agrees that “counseling Michigan women to have abortions in other jurisdictions” would be legal if “the abortions were committed in jurisdictions where the abortions were legal.”

U-M counselors pointed students to two clin ics in New York—Women’s Services, and Eastern Women’s Center, both of which were visited and thoroughly evaluated by a team from U-M. Archived documents explain procedures, costs, transportation, and instructional details such as, “Go to TWA ticket counter, upper level, and look for a woman wearing a pink smock, carrying a clip board . . men picking patients up at the airport. Go only with the woman counselor.” (This instruction was

Pregnancy coun seling practices and legal issues were discussed and debated at U-M prior to the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, which made abortion legal, and which was recently overturned.

spelled out in a 1972 campus memo from Scott to “Problem preg nancy and abortion counselors.”)

One reason counselors likely felt they had to highlight trusted clinics was that sketchier ones were, at the time, frequently adver tising in The Michigan Daily

“The abortion clinics in New York that were advertising were generally for-profit ventures of dubious quality, and there are a lot of accounts of people getting hurt at these clinics,” says John son-Levy. “And part of the concern of the counseling department was that there was no counseling that went along with this. So they were also concerned with the emotional well-being of students.”

Indeed, in a 1971 counseling packet issued by Scott, he spelled out his “Counseling Technique and Style Pertinent to this Prob lem,” wherein he explained that women are often wary of counsel ors who moralize or just hand out information.

“My own intent,” he wrote, “is to communicate an interest in the whole situation by taking as much time as the woman wants, and by inquiring into how and what she has been thinking about vari ous aspects of her situation.”

Scott echoed this notion in his letter to the physician father

COLLECTIONS IN THE STACKS

COUNSELING SERVICES (UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN) RECORDS

Between the Stars and the Sea

In the early 1900s, a deter mined professor of astron omy undertook the ambi tious quest to build a new observatory abroad when U-M’s own observatory in Ann Arbor was threatened by a coal power plant. The result was an observatory in South Africa with U-M ties and a fascinating legacy.

By Julie Halpert

By Julie Halpert

IN 1926, WILLIAM J. HUSSEY, a professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan, stopped off in London. He was headed to South Africa to oversee the construction of a new observatory—a long-held dream. But on October 28, he collapsed during dinner and died from a heart attack at the age of 64.

Hussey wouldn’t have ventured so far if he hadn’t been so angered by a decision by the University of Michigan Regents. His three-year quest to build an observatory in the Southern Hemisphere was prompted in large part by their insistence on building a coal power plant near the Detroit Obser vatory in Ann Arbor, despite his concerns that it would lead to pollution that would obscure stargazing.

“It meant that his dream of having a pow erful observatory within walking distance

26 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU IN THE STACKS

of Central Campus where you could train students was largely at an end,” says Rudi Lindner, Professor Emeritus of history and astronomy, who has delved through vol umes of historical data on Hussey resulting in a comprehensive article in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage titled “Rebuilding Astronomy at Michigan, from Hussey to Goldberg” (2003).

This sent Hussey on a mission to create a first-class observatory elsewhere, and he scoured the globe for the perfect location in the Southern Hemi sphere—especially one he felt would be ideal for his work catalog ing double stars (he would discover and measure 1,327 of them over the course of his career).

OPENING AS PLANNED

including during the Great Depression. Lamont, who was Secretary of Commerce in the Hoover administration, found he could no longer continue to bootstrap it. The Uni versity of Michigan couldn’t be counted on to swoop in and rescue it, either. State rev enues had fallen, causing severe cuts in the University’s budget.

Rossiter’s ingenuity ultimately saved the day. He secured funding from the city of Bloemfontein and the Union Government.

return the refractor lens from South Africa back to Ann Arbor, thinking it could be used somewhere else, but no use ever came of it. It’s still in storage on Central Campus.

After the Lamont-Hussey Observatory closed and the telescope was disman tled, parts of the refractor were on display at the Ehrlich Park Fire Station Museum in Bloemfontein until it was re-erected as a sculpture outside the Lamont-Hus sey building. “I don’t think the [telescope and the refractor] will ever get together again,” Seitzer says.

“THE FUTURE OF ASTRONOMY RESTED ON SITES THAT HAD GOOD WEATHER ABOVE THE CLOUDS AND CALM ATMOSPHERE, AND THERE WAS NO PLACE LIKE THAT EAST OF THE ROCKIES.”

To build his dream, Hussey tapped the resources of his wealthy friend, Robert Lamont, a fellow engineering student at the University of Michigan, who became his benefactor.

One possibility for their new observatory was Argentina. But Lamont liked the idea of South Africa.

In 1923, Hussey headed there and set tled on Naval Hill—a rural mountaintop in a town called Bloemfontein. The height kept it free from the lights and smoke of the city. Together, he and Lamont started building the Lamont-Hussey Observatory.

In 1926, Hussey, along with a younger colleague named Richard Rossiter, whom he recruited to work on the project, shipped a 27-inch refracting telescope to the future site in August. It was then the largest telescope south of the equator.

Things were progressing nicely until two months later when Hussey died in England. “It’s a great tragedy that Hussey died on his way to Africa,” Lindner says.

Lamont decided to proceed because they had already begun construction in South Africa. Freshly grieving, Lamont saw the project to completion along with Rossiter, who understood Hussey’s vision.

The Lamont-Hussey Observatory opened as planned in South Africa in 1928. Rossiter was its director until 1952.

Rossiter managed to continuously resus citate the observatory throughout the years when circumstances were particularly dire,

Ultimately, the University of Michigan started providing half of the financial sup port beginning in 1944 and assumed full financial support in 1952.

A DETERMINED VISIONARY

The University of Michigan ultimately closed the Lamont-Hussey Observatory in the 1970s as a political response to Apart heid in South Africa. Patrick Seitzer, Pro fessor Emeritus of astronomy explains that other factors led to its demise as well.

At the time, there was little interest in dou ble-star observations among the faculty. The University also had a far more scien tifically productive telescope in Chile. “A 27-inch visual refractor had little scientific potential going forward,” Seitzer says.

Though he felt the University could have handled the power plant situation better, Lindner said that Hussey would have always wanted to build the southern station and that the Detroit Observatory ultimately had significant limitations. Hussey couldn’t have imagined that the city would expand to the east—sprouting dorms and a hospital. “The future of astronomy rested on sites that had good weather above the clouds and calm atmosphere, and there was no place like that east of the Rockies,” Lindner says. “In the end, with the increase in urbanization, it just wasn’t going to work out.”

Seitzer says that the University decided to

After it closed as an observa tory, The Lamont-Hussey space was initially used as a theater for local productions, Seitzer says. In 2013, money was provided from within South Africa to convert it into a digital planetarium. Seitzer was there for the inauguration in November 2013. “It was the first digital planetarium in southern Africa and sets the standards for many others to follow,” he says.

Seitzer adds that the observatory in South Africa became an important legacy for Hussey. More than 5,530 double stars were discovered there. Later, the 27-inch refractor would be used for studies of Mars, including taking some of the first color pic tures of the “red planet.”

“Hussey really brought Michigan astron omy into the 20th century,” Seitzer says.

Lindner adds, “He was a determined visionary. And his vision for a future of astronomy in the Southern Hemisphere is an important legacy.”

27BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU DETROIT OBSERVATORY (UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN) RECORDS COLLECTIONS IN THE STACKS

Zebras trot in front of the LamontHussey Observatory in South Africa, which opened in 1928.

A Matter of Pride

A collection of newly donated photos showcases the richness of African American fraternities at U-M and the social pride found in off-campus housing.

By Brian Williams

RICHARD HILL JR. WAS A U-M LAW STUDENT from 1908 to 1911. He excelled academically and was recognized for his oratory and debate skills. A proud alum, he kept a scrapbook from his years at U-M containing photo graphs of his Law School class, campus events like the Senior Smoker, and the freshman-sophomore spring games, along with candid photos of classmates and a few images of himself. Many of the candid images were taken in and around the off-campus boarding house where he resided at 1017 Catherine Street.

After graduating, Hill eventually moved to Chicago to practice law and remained in practice for more than 50 years. Throughout his life, he retained his Michigan photos.

Eighty years after Richard Hill Jr. graduated from the University of Michigan Law School, his grand daughter, Dr. Sharon F. Patton, arrived in Ann Arbor as an associate professor with a joint appointment in the History of Art Department and the Center for Afroamerican and African Studies. Prior to coming to Michigan, Dr. Patton was Chief Curator at the Studio

Museum of Harlem, a leading research center for Afroamerican art. Dr. Patton recalled that after she arrived in Ann Arbor in the fall of 1991, the first place she wanted to find was the fraternity house where her grandfather lived while he was a law student.

She had, after all, inherited his beloved scrapbook and photographs.

Dr. Patton found that the campus had changed greatly in the eight decades since her grandfather completed his law degree. The Law School building where his classes were held burned down in 1950. His boarding house at 1017 Catherine fell to the wrecking ball in 1963. And there had been some progress too: U-M established the Center for Afroamerican and Afri can Studies in 1970, a direct result of student demands during the first Black Action Movement strike in 1970. Dr. Patton was named its director in 1996. In 2011, it became a department.

Dr. Patton left Michigan in 1998 to lead Oberlin College’s Allen Memorial Art Museum. She kept her grandfather’s photos through various moves, includ ing relocating to Washington, D.C., to serve as Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art from 2003 to 2008.

As a historian, Dr. Patton knew that her grandfa ther’s photographs were significant. She hired a resto ration technician to make enhanced digital versions of some photos that were damaged.

Dr. Patton reached out to the Bentley in the spring of 2022 to explore the possibility of donating the photos. She began by sharing some examples of the digitized images. Bentley archivists were ecstatic when they saw the photos. They were the earliest pho tographs Bentley archivists had seen of African Amer ican students living off-campus.

“The Bentley holds earlier images of African Ameri can students, senior portraits, and some group photos,

While some of the faces in Richard Hill’s photos are known to us, many are not. The captions here provide names when possible, and we welcome your help identifying more individuals. Please use the online form at: aasp.bentley. umich.edu

(Left to right)

Richard Hill (front row, far right) at the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity banquet on April 10, 1910.

Unidentified women and Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity member.

Richard Hill (bot tom left) with a group on steps of the house at 1017 Catherine Street.

Richard Hill (right) and an unidentified woman.

Julius Guy Bowley, a 1913 homeopathic M.D. graduate.

The “senior smoker” social event, 1911.

28 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU PROFILES

but they are usually formal, posed photos,” says Bentley archivist Greg Kinney. “Hill’s photos offer a significantly different glimpse of informal African American life off-campus, particularly life at 1017 Catherine Street, a prominent address in the story of African American students at Michigan.”

A SHARED HISTORY OF A BOARDING HOUSE AND FRATERNITY

The two-story house at 1017 Catherine Street, located near the Uni versity Hospital, was owned by local African Americans who rented rooms to African American students. In 1908, six students living in the house sent an inquiry to the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity chapter at Cornell University about establishing a chapter at the University of Michigan. (Alpha Phi Alpha, the oldest historically African American fraternity, was established at Cornell two years earlier.)

The Michigan petitioners received a favorable response. The Epsilon Chapter at Mich igan was chartered April 10, 1909, the fifth chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha. The house at 1017 Catherine was the focal point, oper ating as the chapter house in its nascent days. It was also the site of the Fourth Annual Convention of Alpha Phi Alpha in 1911. A photo of the convention delegates standing on the steps of the Catherine Street house was published in the February 1913 issue of The Crisis magazine.

Hill was part of the first class of members initiated into the Epsilon chapter on November 13, 1909. His photos provide a remarkable lens into the early days of the first African American fraternity on campus. (It would be the only African American fraternity on campus until 1921, when the Phi chapter of Omega Psi Phi was established, followed a year later by the Sigma chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi.)

gle,” a program for the first annual banquet in 1910, and a program for a 1911 house party. Among the photos are a formal image of the 1910 banquet that marked the first anniversary of the Epsilon chap ter’s founding, and the 1911 house party, both taken by Ann Arbor studio photographer Alford S. Lyndon.

The printed program for the April 1910 anniversary banquet details the menu (oyster patties, chicken a la Maryland, little gem peas, potato croquettes, plus Manhattan cocktails and cigars), and the various toasts and toastmasters. Hill’s toast to the seniors was titled, “Survival of the Fittest.” The back of the program contains the words to a fraternity song specific to Michigan, includ ing the phrase, “Three in one and one in three, Epsilon and Michigan and our fra ternity.” The banquet photos depict 18 serious looking men extremely proud of their young fraternity.

Since 1988, the Bentley has held a bound volume of Epsi lon chapter minutes dating from 1908 to 1927. The minutes infuse the banquet photo and program with behind-the-scenes planning details. The social com mittee reported that men were to “be in full dress” and convene in the banquet hall by 8:00 P.M. Additionally, the social committee was tasked with arranging for a photographer.

A HISTORIC DONATION

Thanks to the generosity of Dr. Patton’s donation, the Bentley received 50 images relating to Hill and his Michigan years. Beyond giving the archive the earliest known images of Alpha Phi Alpha at Michigan, some of the other photos have helped identify new names for the Bentley African American Student Project database (aasp.bentley.umich.edu).

29BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU PROFILES

“HILL’S PHOTOS OFFER A SIGNIFICANTLY DIFFERENT GLIMPSE OF INFORMAL AFRICAN AMERICAN LIFE OFF-CAMPUS, PARTICULARLY LIFE AT 1017 CATHERINE STREET, A SIGNIFICANT ADDRESS IN THE STORY OF AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDENTS AT MICHIGAN.”

RICHARD HILL JR. COLLECTION

Big Fish

Jacob Ellsworth Reighard transformed the study of zoology at U-M and left a collection to prove it.

By Lara Zielin

IF YOU WERE STUDYING ZOOLOGY AT U-M in the late 1880s, you might find yourself poring over drawings in books and memorizing various parts of animals on the page. From these same books you might learn the systematic catego rization of animals or their natural history. In lectures, the instructor would have you recite these facts, over and over.

At least until 1889, when Jacob Ellsworth Reighard was appointed professor of zoology. He not only added dissection and lab work to the curriculum—having students actually touch and examine samples of the animals they were studying—but made zoology its own independent research department at U-M.

To further improve zoological research methods, Reighard developed new photog raphy techniques to photograph embryos, breeding fishes in their natural habitats, and coral-reef fishes by means of a submerged camera, which he devised.

But for all the ways he advanced the field, Reighard also used watercolors and paper to depict species of fish. These undated works of art show various types of “sunfish” or euporna tis gibborus, according to the notes on the back of the painting. (This etymology may no longer be correct against modern scientific standards.)

Reighard would go on to help found the U-M Biological Station on Douglas Lake and become its first director. He led the Michi gan Fish Commission from 1890–94 and was appointed director of the biological survey of the Great Lakes in 1898. He was responsible for introducing modern zoological teaching and research at U-M and received an honorary degree of Doctor of Science in 1936.

Reighard died February 13, 1942, but his zoologic legacy— and paintings—live on in his collection at the Bentley.

A seemingly surprised sunfish is part of Jacob Reighard’s water color paintings in his collection.

30 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU BENTLEY UNBOUND

JACOB E. REIGHARD PAPERS

Beam Me Up, Bentley!

How real-life science in spired Star Trek writers to invent the holodeck and, along the way, re-shaped everything from eye exams to aircraft design.

By Madeleine Bradford

IMAGINE A SPACE THAT COULD BE ANYTHING you want: the misty streets of London. A film noir. A Wild West town. A baseball diamond.

That’s the holodeck, an imaginary room on the television show Star Trek Enter prise. The holodeck projects a holographic area that acts like a physical space, fueling many of the show’s plots and escapades.

But Bentley papers reveal that, without the University of Michigan, the Star Trek holodeck wouldn’t exist.

To understand why, first imagine a group of scientists, staring at a train that isn’t actually there.

It looks just like a small model of a train. It’s vivid as life. You could wave a hand right through it.

It is, in fact, a hologram.

Invented in 1963 by U-M Profes sors Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks at Willow Run, and displayed in 1964,

holography was a groundbreaking discov ery. Previous attempts had been blurry, because most available light sources couldn’t create a clear enough image.

Their solution? Lasers! They offered a three-dimensional view so crisp that, when Leith later showed a holographic micro scope to a class of children, they were sur prised when they couldn’t turn the knobs. Their thank-you note survives in Leith’s papers, alongside explanations of how holo grams work.

On a basic level, holography is about capturing interactions between beams of light. Two lasers are needed.

The first laser shines across the object that will become the hologram. The other laser shines on the photographic plate. The two beams meet on that plate, creating what is called a “pattern of interference,” capturing a three-dimensional image.

With the hologram “Toy Train,” the field of optics changed forever. Scientists queued excitedly to take a peek; the glass plate recording of it now lives at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. It inspired progress—and imaginations.

Enter Gene Dolgoff.

A scientist interested in 3-D photog raphy, Dolgoff was immediately curious about holography.

“I called up the researcher who had made the first hologram, Emmett Leith, at the

University of Mich igan,” Dolgoff says in an interview transcription on the official CBS Star Trek website. “We became very good friends over the phone, and I started learn ing all about holography. He totally opened up my mind into a new world of physics.”

Professor Emmett Leith demonstrates how holography works using a small building from a toy train set.

Dolgoff started experimenting. His holo graphic work drew attention, and he was soon introduced to Gene Roddenberry— best known as the creator of Star Trek.

Imagine a place where you could walk around in a completely holographic space, Roddenberry and Dolgoff mused. From their imaginations, the Star Trek holo deck emerged.

Holograms might inspire science fiction, but they’re also used in eye exams, in foren sic science, in aircraft design, in movies— and Dolgoff himself even invented the version used on your credit cards.

In true visionary fashion, Leith and Upatnieks didn’t just change reality. They also allowed people to imagine what reality could become.

To learn more about the invention of holography, take a look at the Emmett Leith papers, and the Juris Upatnieks papers, which discuss how holograms shaped history.

31BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS BENTLEY UNBOUND

HS8477

DID YOU KNOW THE BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY IS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC BY APPOINTMENT?

This means all researchers are welcome in our reading room. All you need to do is request an appointment here: myumi.ch/z1jDR

Once you submit your request, a member of our Reference staff will be in touch with you to confirm the appointment.

WHEN VISITING IN PERSON, PLEASE REMEMBER TO:

Complete a ResponsiBlue screening check on the day of your visit.

Bring a photo ID to show check-in staff.

Wash your hands before beginning your research. Hand sanitizer is also available.

There is free parking at the Bentley if you have a parking permit. We will issue a permit to you when you arrive.

WHERE MICHIGAN’S HISTORY LIVES

Do You Have Michigan History to Share?

The Bentley is once again accepting donations of materials. More than 11,200 donors have entrust ed us with their unique collections. Find out if what you have is right for the archive.

TO DONATE MATERIALS THAT ARE RELATED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN: Call Aprille McKay at 734-936-1346 or email

TO DONATE MATERIALS THAT ARE RELATED TO THE STATE OF MICHIGAN: Call Michelle McClellan at 734-763-2165 or email mmcclel@umich.edu

YOU HAVE

NEED

REFERENCE STAFF: BENTLEY.REF@UMICH.EDU

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT TO RESEARCH AT THE BENTLEY

n

n

n

aprille@umich.edu

IF

QUESTIONS OR

ADDITIONAL ASSISTANCE, PLEASE EMAIL OUR

COLLECTIONS, the magazine of the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, is published twice each year.

Nancy Bartlett

Interim Director Lara Zielin Editorial Director

Patricia Claydon, Ballistic Creative Art Direction/Design

Copyright ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan

ARTICLES MAY BE REPRINTED BY OBTAINING PERMISSION FROM: Editor, Bentley Historical Library 1150 Beal Avenue Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2113

PLEASE DIRECT EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE TO: laram@umich.edu 734-936-1342

Regents of the University of Michigan

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods

Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc

Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor

Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor

Sarah Hubbard, Okemos

Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms

Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor

Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor

Santa J. Ono, ex officio

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office for Institu tional Equity, 2072 Administrative Ser vices Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-6471388, institutional.equity@umich.edu. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.

Land Acknowledgment Statement

The Bentley Historical Library acknowl edges that coerced cessions of land by the Anishnaabeg and Wyandot made the Uni versity of Michigan possible, and we seek to reaffirm the ancestral and contemporary ties of these peoples to the lands where the University now stands.

To increase public understanding of historical events and leaders, the Bentley has undertaken an unprec edented commitment to the digitization of its hold ings and to the production of events—both virtual and live. This includes the Bentley magazine and its digital newsletter, virtual and in-person public events at the library and at the Detroit Observatory, exhibits, pub lic-facing digitization projects, and much more. Your support makes historical evidence accessible, understandable, and relevant. PLEASE USE THE ENCLOSED ENVELOPE OR GIVE ONLINE TODAY. bentley.umich.edu/giving 734-764-3482 SUPPORT THE BENTLEY’S WORK SHARING ITS ARCHIVAL TREASURES. Access Matters +

Where Michigan’s History Lives

A SIGNIFICANT SCRAPBOOK

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN 1150 BEAL AVENUE ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48109-2113

Every day, people use the Bentley Historical Library to explore history. With more than 70,000 linear feet of letters, photographs, books, and more, the Library is a treasure trove of primary source material from the State of Michigan and the University of Michigan. We welcome you to uncover Michigan’s history here. The Bentley Historical Library is open to the public by appointment only. REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT ONLINE myumi.ch/Z1jDR EXPLORE COLLECTIONS AND FINDING AIDS ONLINE bentley.umich.edu FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL facebook.com/bentleyhistoricallibrary @umichbentley @umichbentley MAKE A GIFT bentley.umich.edu/giving 734-764-3482 ABOUT THE BENTLEY

Dr. Sharon F. Patton recently donated photos of her grandfather, Richard Hill Jr., and his time at the University of Michigan from 1908–1911. These images offer a rare glimpse of informal African American life at U-M, especially at off-campus addresses important to African American students. Read more, see additional photos, and help us identify who’s in them on page 28.

By Jenn McKee

By Jenn McKee

By Jenn McKee

By Jenn McKee

By Julie Halpert

By Julie Halpert