17 minute read

A champion of collaboration and conservation

Rebecca Harcourt interviews John Arnott, Manager Horticulture at Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria Cranbourne Gardens

John has been involved in public botanic gardens as a horticulturalist since 1980, is a founding member of BGANZ and is heavily involved with the Care for the Rare program.

John, where does your passion for plants come from?

John Arnott. Credit: Amy Akers.

Vegetable gardening as a kid! When I was five, we moved to Melbourne from Scotland and grew veggies like everyone else in 1960s Australia. I recall digging potatoes and marvelling at their magnificence coming out of the sandy soil. We lived in an old farmer’s cottage in suburban Frankston, with a huge garden with mature Morton Bay figs, gingkos and lemon scented gums. It was almost like an arboretum. I had an inherent curiosity about nature and then there was this rich physical environment. I think this is where my passion for plants and gardening comes from.

You started your career in a zoo. How did this affect your views on plants and horticulture?

I started at the Melbourne Zoo in 1980 as a young apprentice gardener. It was an environmentally barren place, with pits, concrete bars and cages. It was barbaric, however, Melbourne Zoo and zoos around the world were re-imagining the zoo experience through the advent of naturalistic enclosures where the resident animals are displayed in curated exhibits that aim to both provide environmental enrichment opportunities alongside the creation of immersive ‘natural’ settings. By the late 1980s a whole new horticultural discipline emerged, called zoological horticulture. Previously horticulture and animal husbandry had been two separate units. Horticulture was about ornamentation, gardens and floral beds, lawns and amenity, while animal husbandry was about animals in cages. This zoological horticulture movement brought those two things together. In 1985, for the first time at the Melbourne Zoo, and possibly for the first time globally, the success of a zoo exhibit – the butterfly house − was contingent on horticulturists.

We had to grow the larval food plants, a huge horticultural challenge as many of these larval plants had never been cultivated before. It was remarkable, and it revealed this world to me where horticulture is more than just ornamentation.

Article from The Melbourne Age, December 1992.

The last known wild population of Diuris fragrantissima is located in this remnant grassland reserve along a section of rail line to the west of Melbourne. Credit: Noushka Reiter.

Is that where you became interested in conservation?

Absolutely. The zoo was starting to talk about conservation of animal species and I thought, why doesn’t zoo horticulture include the conservation of plant species? Indeed, we did some really innovative things at the zoo around plant conservation. As an example, there’s a plant called Diuris fragrantissima, or Sunshine Diuris, an orchid, formally known as Snow in the Paddocks. Its natural range was several hundred square kilometres, just to the northwest of Melbourne. It was never widespread, but it was locally common, to the point where when it flowered it turned the paddocks white. Through processes such as agricultural displacement and urbanisation it rapidly declined to the point where it was restricted to one tiny reserve, which was wedged between two train lines in industrial western Melbourne. That’s the last place that this plant was surviving in nature. I just happened to know someone at La Trobe University nursery who gave us some plants that were recovered from that site as conservation holdings. We then witnessed an incredible pollination and germination event − the handful of plants was quite miraculously now an ex situ population of 600−800 individuals. We had 99.9% of the world population of this species sitting on a bench in a zoo in urban Melbourne! This bench was a kind of backstop to extinction of the species. It was extraordinary. That material has since supported the recovery of the species and it’s been translocated into a few secure reserves to the west of Melbourne. It was a serendipitous side project, very grass roots, but ultimately so successful the zoo built a glasshouse and it became part of the integrated conservation role of the zoo. It involved individuals collaborating as individuals but being supported by institutions, a theme I’ve seen repeated in successful conservation projects over the last 40 years.

What role do you think botanic gardens have in conservation?

There’s a term called integrated plant conservation, which is about using a whole range of different tools and techniques for conservation outcomes − in situ conservation, ex situ conservation, research and community education. Some of those might be out in the field, such as the conservation of species in situ, supporting them as self-sustaining populations that are dealing with threatening processes. In the integrated plant conservation tool kit, there’s a whole bunch of things that happen off site, and that’s where botanic gardens come in − the ex situ conservation role. It’s complementary and indeed necessary in some instances, for example, in the case of the orchid I talked about earlier. Since then, the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria (RBGV) has instituted a multiagency orchid conservation program and the Diuris is central to that. This program, driven by Noushka Reiter, is globally recognised as an exemplar species recovery program.

In ex situ living collection holdings, we can understand a plant’s environmental tolerances, how to propagate it and what it requires to thrive and grow. You can learn a lot about a plant outside its natural range. Ex situ living collections also raise public awareness of threatened species. Raising Rarity is a project the RBGV is undertaking where we assess the home garden potential and the ornamental capacity of our threatened flora. The aim of the project is to make a range of suitable threatened plants available in commercial retail nurseries. There’s a sense of participating in plant conservation, but at the same time promoting an awareness of our threatened flora. The Wollemi Pine project is an absolute example of the benefits of conservation through cultivation. It’s taken a threatened species and commercialised it at the same time as communicating its inherent value and conservation significance, to the point where an entire country now values this plant.

These ex situ living collection holdings are greatly enhanced with material of known wild origin and the conservation value of such holdings increases with representation of genetic diversity. You couldn’t just go to a single plant, take seed off it and clone it, because that will represent such a narrow slice of the genetic footprint of that particular species. Decent ex situ holdings are typically quite complex as they need to capture the genetic variations of the population. This is where the idea of meta collections comes in. For example, some of the taxa affected by myrtle rust are recalcitrant, with fleshy fruit that can’t be stored in fridges. They have to be held as living collections in ex situ holdings. An individual garden would struggle to hold the several hundred living plants necessary to represent the population, so the aim is to distribute this diversity around the network as multi-site collection holdings − a meta collection [see The ‘Cloud Forest’ of Cranbourne, as an example, in this issue].

The role of botanic gardens in conservation also includes long-term seed storage, such as the Seed Bank Partnership, in which all the states are participating in the long-term safe storage of threatened species and capturing those in ex situ holdings in fridges [see Australasian Seed Science Conference 2021 in this ssue, for the latest research in this area].

How have you seen the world of plants, and native plants, changing across your career?

In 2000, after 20 years at the zoo, I took on the role of Director/Curator of the magnificent Geelong Botanic Gardens. My very first day at Geelong, 10 October 2000, coincided with the inaugural meeting of the Victorian Regional Botanic Gardens Network, which predated BGANZ. Our first task was to survey gardens in the Victorian network to see what collections they were holding. The 1860s and 70s had seen an incredible boom of botanical gardens in Victoria, because of the gold rush. It was about an expression of the maturity of these burgeoning communities, and so Victoria had this incredible spike in botanic gardens all based on the European model. In 1870 there were 20 regional botanic gardens in Victoria, compared with NSW, Tasmania and Queensland, with only one each. Wind the clock forward to 2000 and many of these gardens had legacy collections of European plants. Australian plants were not a feature. Our 2000–2001 survey found an absolute paucity of Australian local plants, let alone native plants, being cultivated across the broad network. In different states it was a very different scene because they didn’t necessarily have the same heritage legacy as in Victoria. We did another survey in 2019 to inform the botanic gardens record project that was seeded by BGANZ Vic. There were significant changes in terms of botanic gardens embracing an Australian native plant agenda and diversifying their collections beyond the legacy of history. Conservation collections had not however developed in Victorian regional botanic gardens to any great extent, which triggered the BGANZ Victoria Regional group to explore further and develop programs targeted to conservation outcomes for the network.

Article from The Geelong Advertiser, Monday 30 January 2006.

You have been instrumental in the Care for the Rare program in Victoria. What is it and where could it go next?

In the 1860s and 70s, botanic gardens in Victoria were more like pleasure parks; places of beauty and public amenity. Collections were developed, but not around taxonomy, science or conservation. They were essentially cultural collections. When the Victorian Regional Botanic Garden Network was established, it was clear that very few regional botanic gardens in Victoria saw themselves as playing a role in plant conservation. The main impediment to this was access to plant material. Essentially, the gardens were being managed as municipal parks. The idea of going into the field, collecting indigenous plants, bringing them back into cultivation and being able to provenance them was too hard. The Care for the Rare project, triggered in 2019, was essentially a sector capacity building project to support regional Victorian botanic gardens to get involved in plant conservation. RBGV applied to the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust to run a pilot project, with 24 of 42 gardens expressing interest in the program. The people involved in the project and selecting the pilot gardens were Justin Buckley from the National Trust, Donna Thomas from the Ballarat Botanic Gardens, Tex Moon from the Dandenong Ranges Garden, David Roberts from RBG Melbourne, Lindy Harris from the Karwarra Australian Native Botanic Garden, and me. The six gardens selected were representative of the broader botanic garden network in Victoria. We selected the Shepparton Botanic Gardens, which at that point was completely community-driven. We also selected the Colac Botanic Gardens, which was one of those 1870s landscapes. Then, we chose Ballarat Botanic Garden with its huge horticultural capacity. Up until that point they’d been really famous for their begonias and for their European landscape. Wilson Botanic Park was also selected, which was an interesting emerging botanic garden in the same local government area as Cranbourne. Sale Botanic Garden, which had been completely transformed in first part of the 21st century, and the latter half of the 20th, was also selected. The final garden was the Dandenong Ranges Garden, which is our newest botanic garden. It was the former national rhododendron garden and is the only true alpine or cool climate garden in our network.

RBGV Landscape Architect Andrew Laidlaw designed the Sale Care for the Rare Garden including preparation of planting plans. The collection focused on showcasing the threatened flora from the Shire of Wellington. Credit: John Arnott.

We went to each of the gardens, consulted with the curators, staff and Friends and developed a conservation collection plan for each. The RBGV Cranbourne Gardens nursery then propagated the plants from the list we had created that responded to the conservation collection/plans. 192 rare and threatened Victorian taxa comprising 3,400 plants were sourced, propagated and produced at the RBGV Cranbourne Gardens Nursery and distributed to each garden. 192 taxa represent over 12% of the state’s threatened flora, now secured and held in conservation collections.

A nice feature, in addition to building conservation collections in each of the six gardens, is that we engaged an interpretation consultant expert to assist each of the gardens in how to message each of the collections to their communities. We reserved some of the funding to support each of the gardens in developing an interpretation plan and having some interpretation collateral to activate each of the collections at each of the gardens. It’s really interesting that the Care for the Rare idea is a now a bit of a brand. In fact, at one of the BGANZ council meetings one of the members referred to Care for the Rare as a movement! It felt incredible to hear that. Other botanic gardens in Victoria are independently developing rare and threatened collections of their local flora, and deferring to Care for the Rare in their collection. Care for the Rare has the potential to be something that brands the role of conservation in botanic gardens beyond the six pilot gardens.

In terms of where the program is going, we hope it will expand. It’s been incredibly successful. For example, until recently, the Shepparton garden had no staff; it was run entirely by volunteers. They have done remarkable things associated with the Care for the Rare project − there are now 27 threatened species sitting in their garden. This has allowed the gardens to go to their council and tell them, we are something other than a park and we need to be resourced. Now they have a staff member.

We’ve learned a lot about how to set up these multisite conservation collections and how to support, encourage and empower regional botanic gardens in getting involved. In fact, BGANZ QLD has asked us to advise them as to how they might implement a similar Care for the Rare program across Queensland botanic gardens.

The Conservation Collections Planning Team at the Australian Botanic Garden Shepparton. L – R: Melissa Stagg, Landscape Designer; Sally Mann, local field naturalist; John Arnott, RBGV; Lindy Harris, Karwarra Gardens; David Roberts, RBGV Melbourne Gardens. Credit: Jill Grant.

Tell us about your work at RBGV Cranbourne and how you developed the master plan for the living collection

In 2008 I moved to RBGV Cranbourne as Manager of Horticulture. My job was to support the implementation of the second and final stage of the Australian Garden.

The original design for the Australian Garden was strongly narrative driven and very much led by the brilliant landscape architecture team Taylor Cullity Lethlean (TCL). The original plantings were developed collaboratively with horticulture staff in partnership with Australian Garden TCL Plant Designer Paul Thompson. Post completing the second stage in 2012, the garden entered a new phase in its development, that of plant and landscape establishment and exploring how the garden was being used by our visitors. At this point TCL and Paul Thompson stepped back from active roles and the Cranbourne Gardens division took full carriage of managing the 21 precincts and their associated living collections. This led us to ask the question, who curates a garden? The answer was not just the gardeners, or the horticulturists – everyone curates a garden. With this the Cranbourne Gardens established an innovative, multidisciplinary approach to Curatorial Management Planning which has successfully guided the development of the living collection and associated visitor experience.

Our curatorial planning team ended up including someone from the executive (Chris Russell), someone from plant sciences, horticulturists, our visitor experience team, our infrastructure people and our natural areas and conservation team. I think the beauty of botanic gardens is that they are multidisciplinary. Each discipline has its own perspective, so they are multi-perspective too.

We established a multidisciplinary team to create a shared sense of understanding. For example, the infrastructure team was interested in things like timber and bridges and through the process they learned the value of the living collection beyond the hard infrastructure. They could see and feel the passion and commitment for a particular plant. When it came to maintenance processes, such as cleaning out a draining pit, for example, they used to just throw the gravel into the garden bed. Now, they understand that the plants might be precious, so they have changed their work practices to avoid this.

Through the master planning process, we realised there was an opportunity for us to introduce conservation horticulture into the living collection, beyond the ornamentation that was inherent in the original design. We could place an emphasis on the flora of SE Australia and Victoria and introduce some ecological and conservation elements into the collection, while understanding and honouring the intent of the designer and original plant selection. The original design was largely an abstraction of nature. The master plan suggested we should be looking at tighter ecological associations within these display gardens and we were given permission to explore that.

There was a horticulture team of about 17 people who were really committed to this agenda and delivered it. It went from a strategy to something that was owned and championed by staff, a shared vision by management, staff and Friends. It was a case of ‘driven by strategy, fuelled by people.’

You’ve been a key member in the evolution of BGANZ and BGANZ Victoria. What are the changes you’ve seen and value?

The Red Sand Garden at RBGV Cranbourne Gardens. Credit: RBGV.

The seed for the idea of a peak industry body or network across botanic gardens in Australia and New Zealand was discussed as the main theme at the Australian Botanic Gardens Congress in 2001 hosted by the Australian National Botanic Gardens in the ACT. The major outcome from the Congress was the formation of an Australian Botanic Gardens Network that ‘evolved’ to also embrace botanic gardens from New Zealand. With that BGANZ was born. The inaugural congress of BGANZ was held at Geelong in 2003 when I was the curator director there. As such I’ve seen it go from an idea to a cohesive network. Its achievement is that it has established itself as the BGCI of Oceania and is now globally recognised as the region’s peak industry body. This recognition has been incremental over time; congress by congress, president by president. We have more than 130 institutional members, the vast majority funded by local government and representing their communities, unlike the major capital city gardens that have a statewide mandate to be a botanical institution. Yet managers of botanic gardens in local government can’t necessarily look to their park manager or even their organisation to secure anything beyond (critical) funding and support, such as guidance and inspiration with respect to how to manage a living collection. BGANZ fills that void. It’s the network that connects each of these botanic garden curators funded by local government, and provides the opportunity for technical support, advice, capacity building, training and moral support. It is like any professional association – it means you are not alone.

What’s your favourite botanic garden, other than Cranbourne?

Alice Springs Desert Park. It connects animals, plants and people and introduces a First Nations voice. It’s where life sciences meets culture.

Finally, what is your favourite plant?

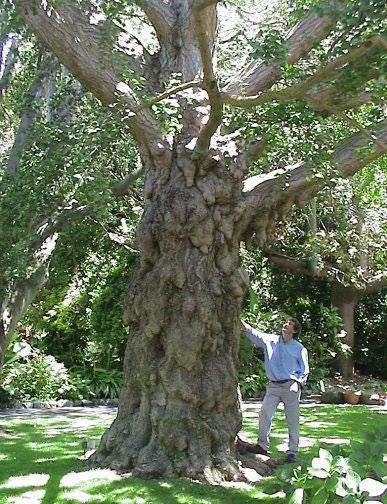

I revere gingkos. They are very biodiverse. There’s one at the Geelong Botanic Gardens that’s remarkable. It is huge, with enormous aerial roots, or truncheons, arguably the finest example of the tree in Australia. Gingkos are ancient plants and are listed as endangered in the IUCN red list of threatened species in the wild. They used to exist all over the world and over millennia, became restricted to tiny, fragmented populations in China. They are another great example of the importance of conservation.

The magnificent ginkgo at the Geelong Botanic Gardens planted by the garden’s first curator Daniel Bunce in the 1850s. Credit: City of Greater Geelong 2001.