6 minute read

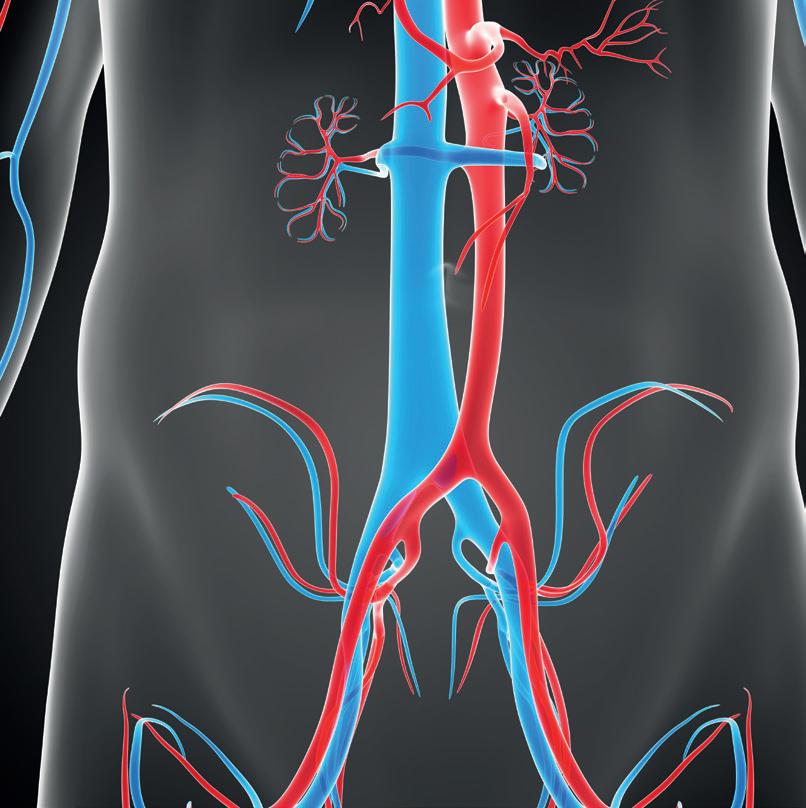

Educate, educate, and educate again: The continuing quest for appropriate venous care

Prominent venous disease experts discuss venous stenting, appropriate care, and the pursuit of refined data and better education in a space where part of the problem involves practitioners moving “freely from being able to do arterial intervention and suddenly assume they can do a venous intervention”.

Education across the venous care delivery spectrum lies at the heart of efforts to ensure operator judgement is optimal and procedures— like the placement of venous stents—are carried out in the appropriate circumstances.

Or, as Steve Elias (Englewood Health Network, Englewood, USA) says, “the trend is going to be perhaps that too many stents are going to be placed for a while until we educate people about when this is appropriate and when it is not appropriate.”

Elias was speaking ahead of the 2023 American Venous Forum (AVF; 22–25 February, San Antonio, USA) where some of the latest data on venous stent usage trends between 2014 and 2021 were presented by Karem Harth (UH Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Cleveland, USA).

Stent migration and overstenting remain recurring themes as new research is presented and surgeons discuss outcomes.

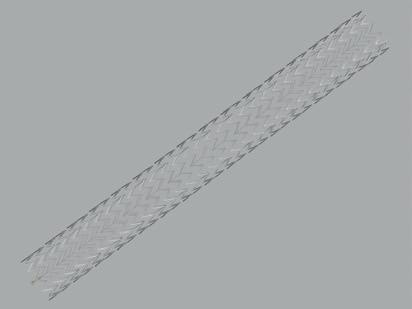

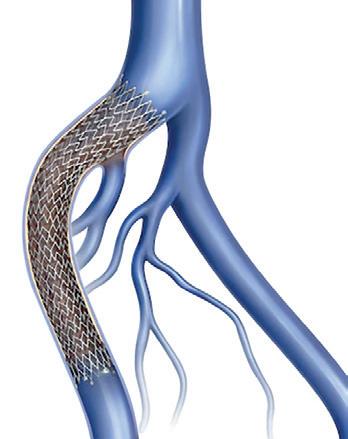

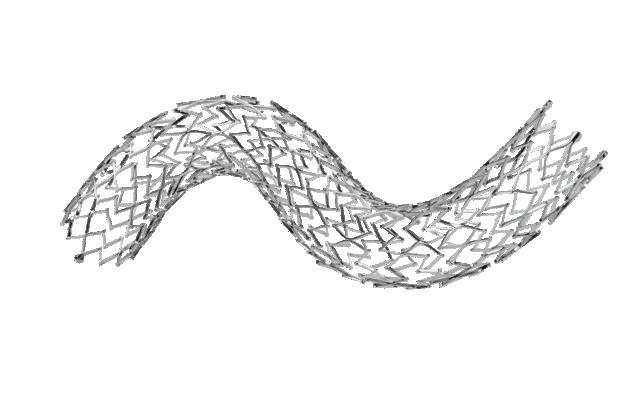

New data from the clinical trial of the Abre dedicated venous stent recently prompted investigator Stephen Black (Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK)—who led the trial with Erin Murphy (Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute, Atrium Health, Charlotte, USA)—to declare that, given the study showed no stent fractures through three years, and similarly, no delayed stent migrations, “… stent migration really does seem to be an operator issue rather than a stent issue”.

Elias underscores the point: 99.9% of the time the issue is not one of the stent but of the judgment of the operator, or poor training—“or an issue of considering venous stents as similar to arterial stents,” he says.

Elias emphasises the role of device makers in education. “Those of us on the leading edge of this are working with all of industry to set up programmes to better educate their salesforces and then also their physician customers regarding not just stents but also venous disease in general,” he says. “We all realise this is a problem and the only way to solve it is by all of us working together.”

Data: From IDEs to RCTs

Over the past decade, venous stenting has evolved from a “byword” into a “mainstream and accepted” practice, Black tells Vascular News. Recently, several on-label, venous-specific devices have become available—four in the USA—along with the first prospective data in the form of investigational device exemption (IDE) trials, and, according to Black, there is now “more enthusiasm for treating patients” among providers in the venous space.

Murphy casts a positive light on how the field has changed over the past five to 10 years, pointing out there has been some “great progress” in technology.

At this juncture, Kush Desai (Northwestern University, Chicago, USA) believes the time to embark on “real-world” studies is now, with the aim of “demonstrating the value of treatment of patients across a variety of disease states from non-thrombotic through post-thrombotic”. He explains that these data will help physicians to “clearly identify which patients benefit and what we can expect for outcomes”.

Black concurs, adding that randomised controlled trials (RCTs) will need to follow, despite the difficulties associated with carrying out such research. The “big problem” here is recruitment—a problem that is affecting various ongoing trials. This recruitment issue is multifactorial, Black notes, specifying that clinicians “feel they do not have equipoise anymore” and among some there is a “financial conflict bias,” while patients “do not want not to be treated.” The solution? According to Black, clinicians need to work as a group to “overcome our own biases,” in order to ensure randomised evidence ensues.

Murphy underlines some specific areas in which data would be beneficial, mentioning the need to determine thresholds for intervention in nonthrombotic disease. She further describes the need for more data supporting good stenting practices, citing intravascular ultrasound as one example. “I think this is something we all agree is essential for good outcomes in this space,” she says, however rigorous data are lacking. She adds that there is also room for “significant improvement” in data encompassing the areas of pre- and postoperative imaging as well as postoperative anticoagulation regimens.

Desai points to the importance of data consolidation, referencing in particular the work of the Deep Venous Academic Research Consortium, which he chairs alongside Black. “The goal of this is to improve the rigour and reproducibility of deep venous research,” Desai explains, by way of ensuring that studies are all collecting the same trial data, so that they can be compared. He hopes that this will create “more sound data” for the devices that practitioners are placing and will thus have a “downstream effect” on clinical practice.

Rabih Chaer (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, USA) notes that “longer-term” data might still be lacking for the individual stents and comparative data between the different stents available for venous placement.

“That becomes important because, at least the newer-generation venous dedicated stents have shown us that some have performed better in certain locations based on the design of the stent,” he says. “There may be some variability in the performance of each stent depending on which part of the vein and for which indication they are used.”

Appropriateness of care central to best practice

In parallel to the need for more data, Desai posits there is “quite a long way to go” in terms of refining venous stenting practice. “The devices are very good,” he says, noting that, while there is “certainly room for improvement,” outcomes across studies are “very similar, sort of agnostic to the stent device”.

Both Black and Desai highlight the importance of understanding the specifics of venous disease when it comes to best practice. “Part of the problem with venous is people move very freely from being able to do arterial intervention and suddenly assume they can do a venous intervention,” Black remarks. “It is like playing squash and tennis,” he analogises, “they are both racket sports with a ball but the rules are not the same”.

According to Desai, the “biggest issues” in terms of practice are with patient selection and disease state recognition. “Simply put, there are far too many stents placed for non-thrombotic disease in the USA, meaning there is attribution of symptoms that are not likely to significantly improve with placement of a stent.” He states that this can be attributed in part to economic benefits to the operators—which he says “may be a uniquely US thing”—however notes that there are “likely a variety of problems at play”.

Murphy believes the field is “findings its way” in terms of best practice. She highlights that, five years ago, there was a “considerable problem” with undertreatment of venous obstruction.

Considering current practice, she agrees with Desai that overtreatment of non-thrombotic patients is an issue, while also noting that practitioners are “still undertreating” the post-thrombotic group. Many of the latter patients are not referred for treatment.

Black stresses that “inappropriateness of care” is the key issue, and that one of the main challenges facing venous stenting practice is ensuring “the right patient is getting the right treatment by people who know how to do it properly”.

Non-thrombotic iliac vein lesions (NIVLs) are at particular risk of overtreatment, he says, because “the impetus is to treat anybody with any leg problem on the left-hand side” when there are lots of patients who do not need treatment. In the case of chronic occlusions and post-thrombotic disease, and potentially acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (DVT), he notes there are lots of patients who are not getting treatment who would “probably benefit”.

Murphy also highlights the importance of appropriate treatment and is confident that, over the next few years, practitioners will “perfect” their patient selection. “I do not think that people are going awry on purpose,” she stresses, instead noting that this is a “developing” field and that the process of “sorting through who is going to get the most benefit” is ongoing.

Education and training

Considering how venous stenting practice can be improved, Desai believes education is key. “I think most providers would be open to the discussion that ‘maybe your stent is not helping patients,’ and would correct their behaviour,” he says, while remarking that it is “much more difficult to correct” the practice of providers who are financially driven. “More broadly speaking,” however, he is confident that education remains central “for providers that are willing to listen”.

Black points out that a number of educational efforts are in place—from company-run symposia and training to workshops at vascular meetings. He stresses however that training is a “twoway thing”. He explains: “You have to engage in training.”

In Murphy’s view, training in the form of “interested” physicians, who are already practicing, shadowing expert practitioners is working well. What is “majorly lacking” in education, she believes, is investment at the fellowship and trainee level, underscoring the need for “dedicated, comprehensive venous training programmes”. She explains that, currently, there are no programmes in the USA that spend a significant amount of time teaching lymphoedema, superficial venous disease, and deep venous obstruction. Programmes that teach all of these aspects in one place, she believes, is “extremely important” for the trainee.

Looking at the wider picture, Black highlights that, while vascular care “continues to suffer from an unreasonable focus on aortic disease,” there is a “huge opportunity in the treatment of venous disease to make a really big difference to a patient’s quality of life”. With this in mind, he encourages “all vascular enthusiasts” to commit to collecting the data, partaking in the training, and delivering the appropriate care that should be the hallmark of venous stenting’s next chapter.