£3.95 WHERE SOLD Actor, Director, Diplomat, Committed Activist, and Legend SIDNEY POITIER www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk

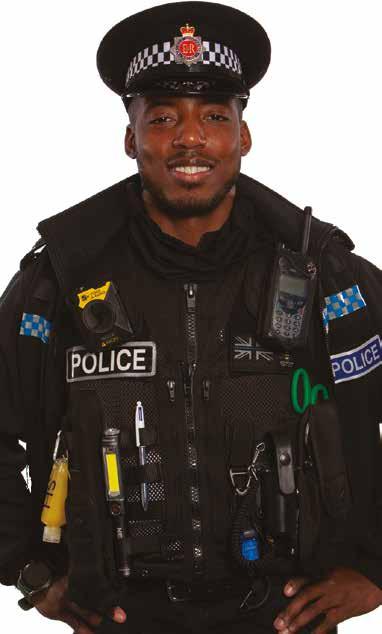

The Army Engagement Group (AEG) tours the country engaging with a wide variety of people to give them a greater understanding of the British Army; who we are, what we do and how we contribute to society. The AEG has four teams that can offer various multi-media presentations and activities, before giving people the chance to meet and talk to some of our soldiers.

THE ARMY ENGAGEMENT TEAM delivers the Army’s flagship multi-media presentation to invited guests from a local community. Each 45-minute presentation is followed by a question and answer session and a reception where you can meet soldiers and ask questions in a more informal setting. Guests are hosted by local members of the Army and presentations are held throughout the year - please contact RC-AEG-mailbox@mod.gov.uk to find out about the next presentation in your area.

THE ARMY BUSINESS AND COMMUNITIES ENGAGEMENT TEAM delivers a more focused version of our flagship presentation to bespoke audiences. The team delivers a 30-minute presentation followed by a question and answer session and can do so virtually or at your location. They can also deliver team-building tasks in support of professional development days. They speak to a wide range of audiences and any opportunity is considered, whether you are an employer, represent a community or network, or are arranging speakers for a larger conference or networking event.

THE ARMY YOUTH OUTREACH TEAM The Army Youth Outreach Team encourages young people to maximise their potential and challenge stereotypes. Working with schools, youth groups, communities and charitable organisations, the team delivers an interactive presentation which explores opportunities available in the Army and highlights the emphasis we place on personal development. The team also delivers various fun, practical activities which aim to develop communication skills, foster teamwork and grow self-confidence.

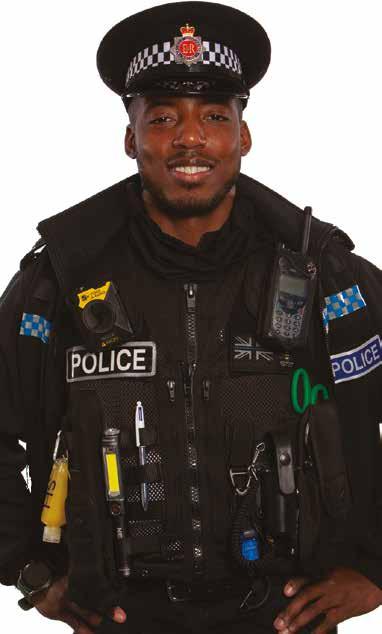

THE ARMY DIVERSITY ENGAGEMENT TEAM The Army Diversity Engagement Team engage and inform mixed audiences and communities, delivering their ‘Strength in Diversity’ presentation, showcasing the Army as a fully inclusive employer. They tackle popular misconceptions and highlight the importance we place on equal opportunities for everyone, regardless of gender, race, sexuality, ethnicity or faith. The Team can also support other activities such as panel events, networking, community support or diversity seminars. Additional bespoke activity can also be discussed.

THE ARMY STEM YOUTH ENGAGEMENT TEAM The Army STEM Youth Engagement Team are drawn from the technical branches of the British Army to promote and encourage STEM within Schools and other educational and youth organisations. They deliver engaging physical and virtual workshops across the United Kingdom to help inspire the next generation of STEM experts. For more information and bookings, please visit www.stemview.co.uk

IS THERE A COST? There is no charge for our presentations or activities and we come with all our own equipment.

HOW TO BOOK Requests for any of the Army Engagement Group’s teams can be made by emailing RC-AEG-mailbox@mod.gov.uk

ADR010008

AEG STEMVIEW

CONTENTS

WELCOME MESSAGE

By Catherine Ross

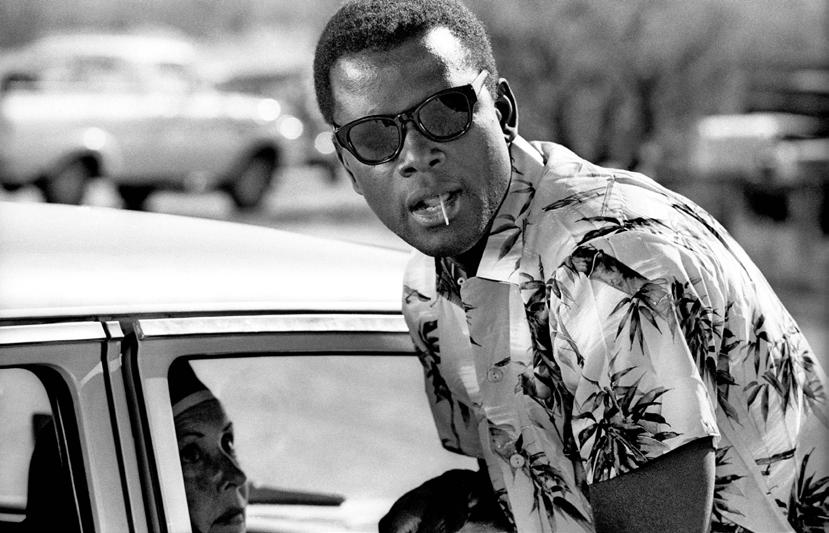

8 SIDNEY POITIER ACTOR, DIRECTOR, DIPLOMAT, COMMITTED ACTIVIST, AND LEGEND

JEBRIL UMO – MY ANGRY BLACK VOICE

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT IN BRITAIN – A POVERTY OF KNOWLEDGE? By Semper Azeez-Harris

18 WANTED: EFFECTIVE ALLIES WHO TAKE MEANINGFUL ACTIONS

By Lynda Burrell

SCRATCHYLUS – RESETTING THE MINDSET HEALING A FRACTURED SOCIETY IN THESE VERY CHALLENGING TIMES

1968 RACE RELATIONS ACT: REFLECTIONS OF A WINDRUSH DESCENDANT

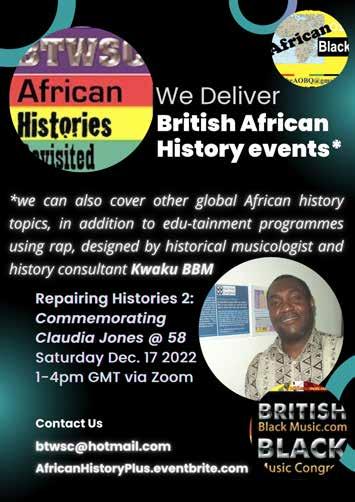

THE HISTORY OF ENCYCLOPEDIAS ON AFRICAN HISTORY: DISPELLING “DARK CONTINENT” MYTHS By Kwaku

28 TAKING A STAND By Councillor Sanchia Alasia

COMMONWEALTH GAMES 2022 A REVIEW OF THE OPENING CEREMONY IN BIRMINGHAM

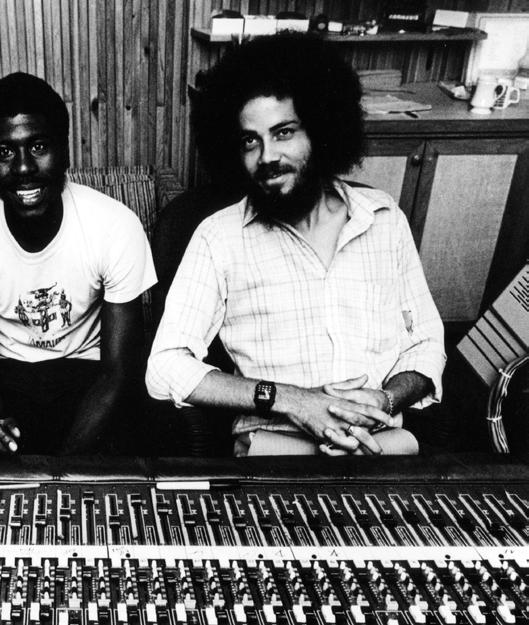

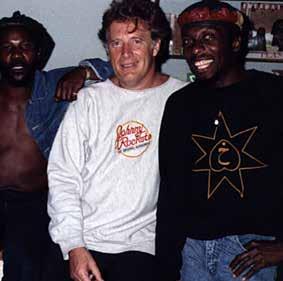

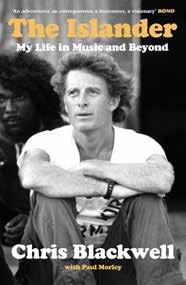

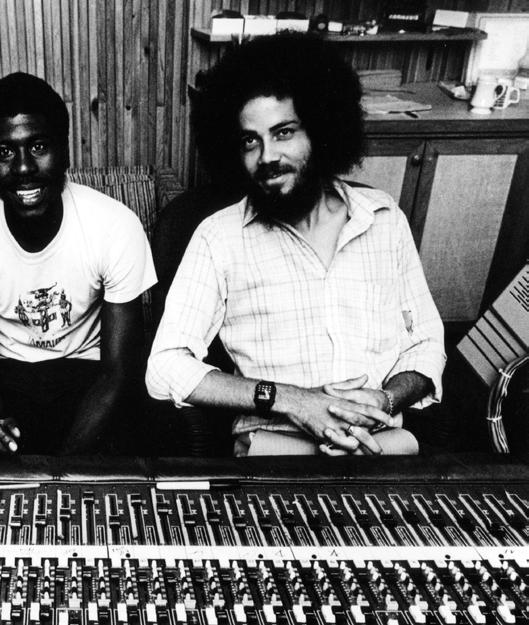

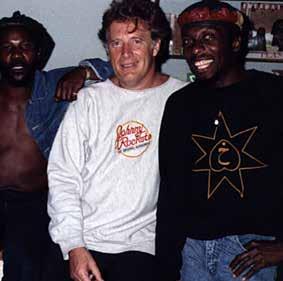

36 CHRIS BLACKWELL – THE MAN WHO GAVE AN ISLAND’S MUSIC TO THE WORLD By Kwaku

40 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE BLACK IN THE 21ST CENTURY?

By Jebril Um0

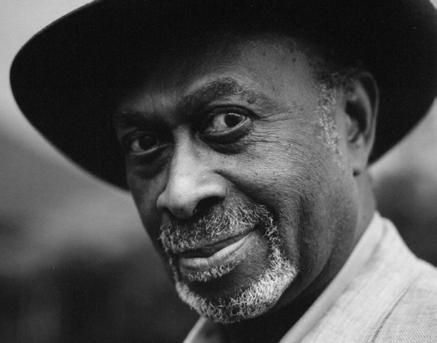

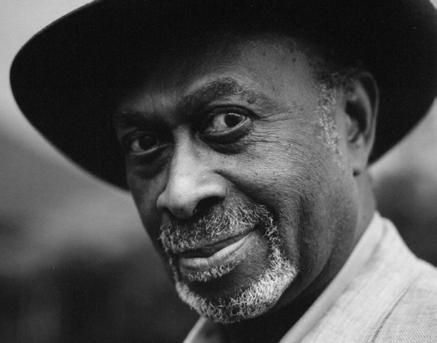

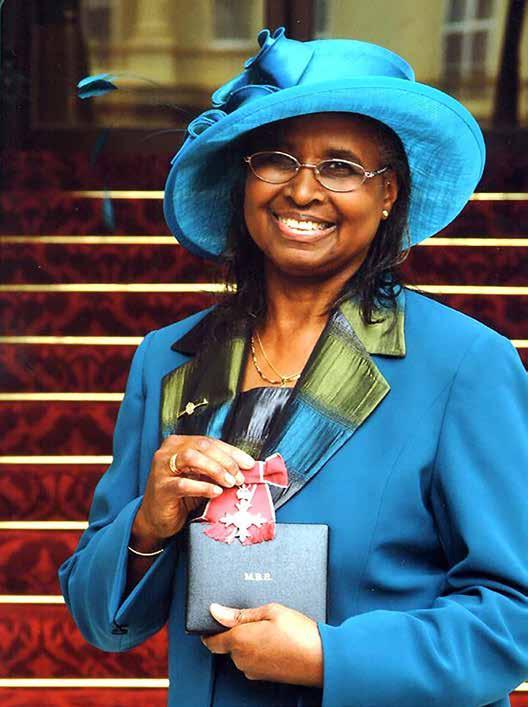

41 ROY HACKETT MBE

WHERE IS BLACK AFRICAN LIFE IN LONDON? By Jimi Famurewa

THE ACTIONS OF ONA By Suzette D. Harrison

THE LATE JAMES BERRY –TO TRAVEL THIS SHIP

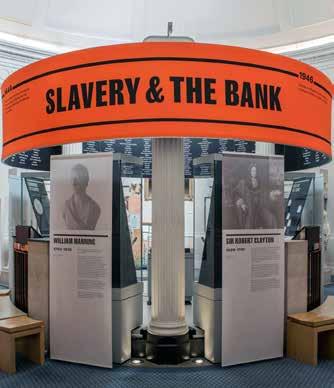

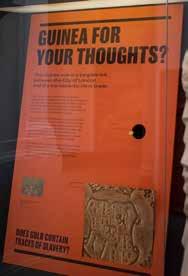

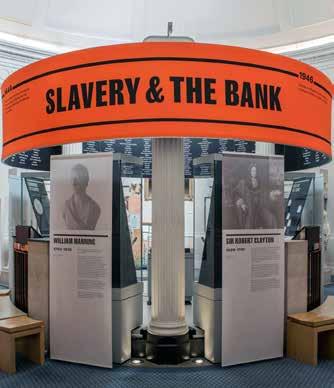

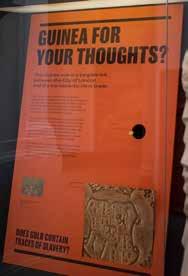

SLAVERY & THE BANK EXHIBITION AT THE BANK OF ENGLAND MUSEUM

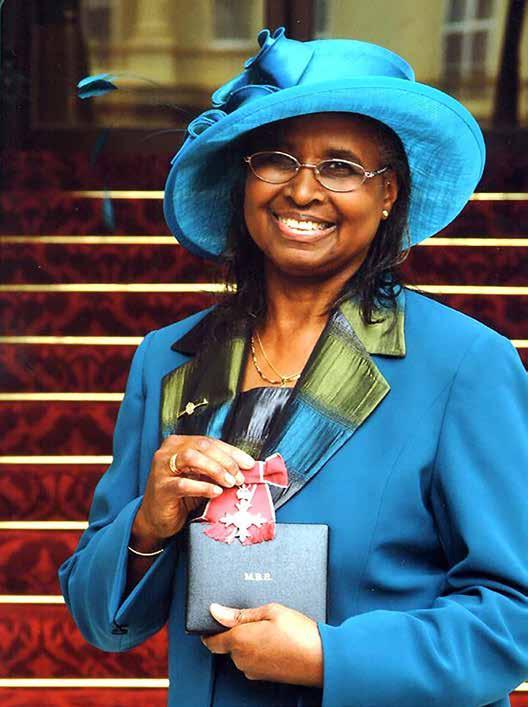

LOUISE DA-COCODIA AND THE DISCRIMINATION FACED BY BLACK NURSES IN THE INFANT DAYS OF THE NHS

BLACK BRITISH JOCKEY ASHLEIGH WICHEARD TAKES THE KNEE BY LYNDA-LOUISE BURRELL

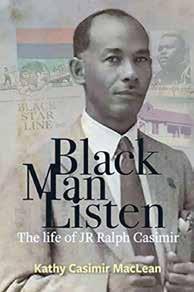

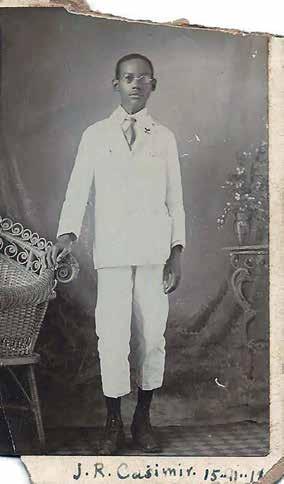

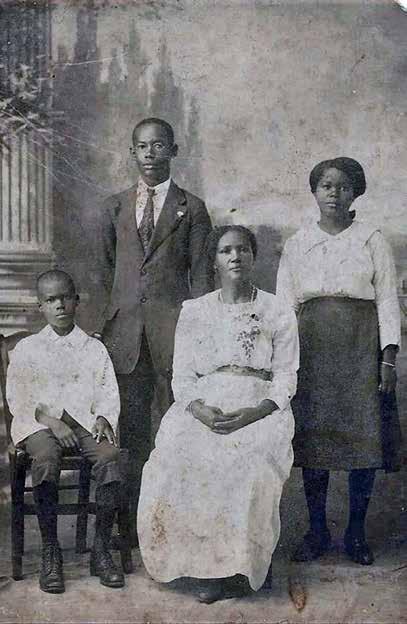

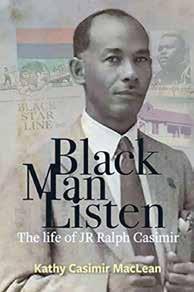

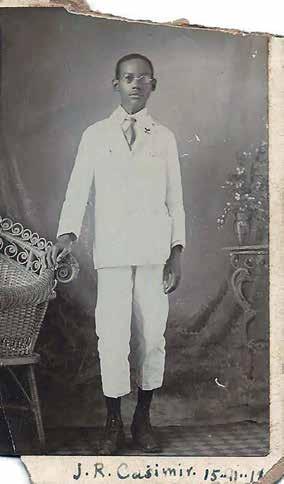

FINDING THE PAST BY KATHY CASIMIR MACLEAN

THE BRISTOL BUS BOYCOTT OF 1963

KEN PITTERSON – FROM RACING ENTHUSIAST TO PADDOCK EXPERT By Catherine Ross

THE WINDRUSH EXPERIENCE EXPRESSED IN MUSIC – FROM 1948 TO 2022 By Catherine Ross

DAL BABU OBE – CHAIR, SEACOLE GROUP

‘GRIME STORIES: FROM THE CORNER TO THE MAINSTREAM’

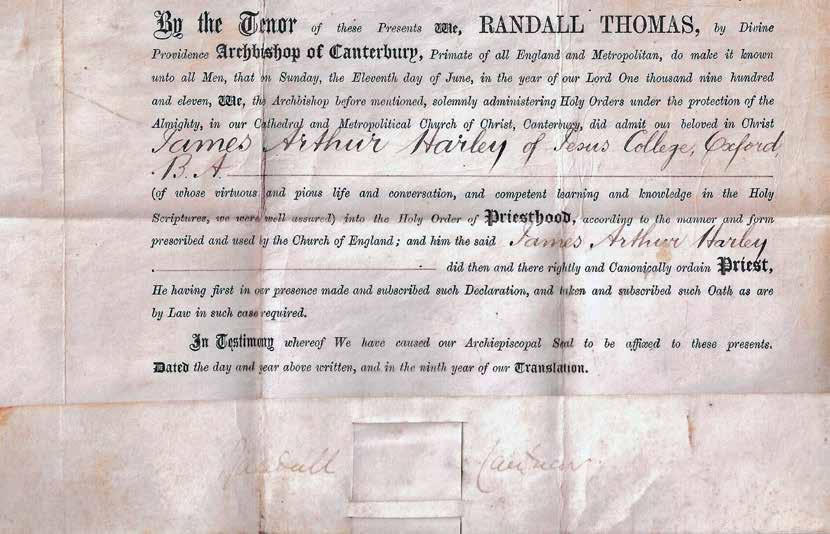

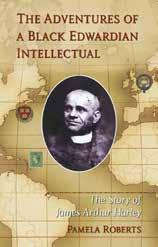

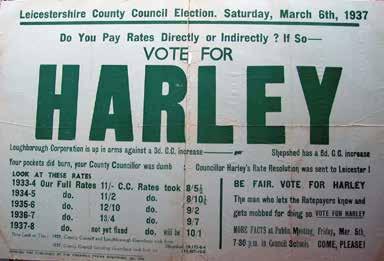

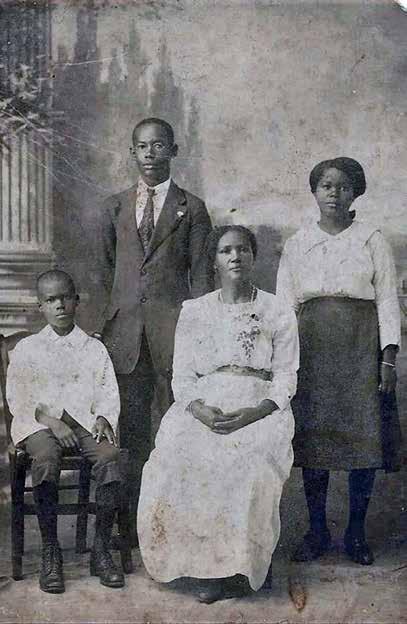

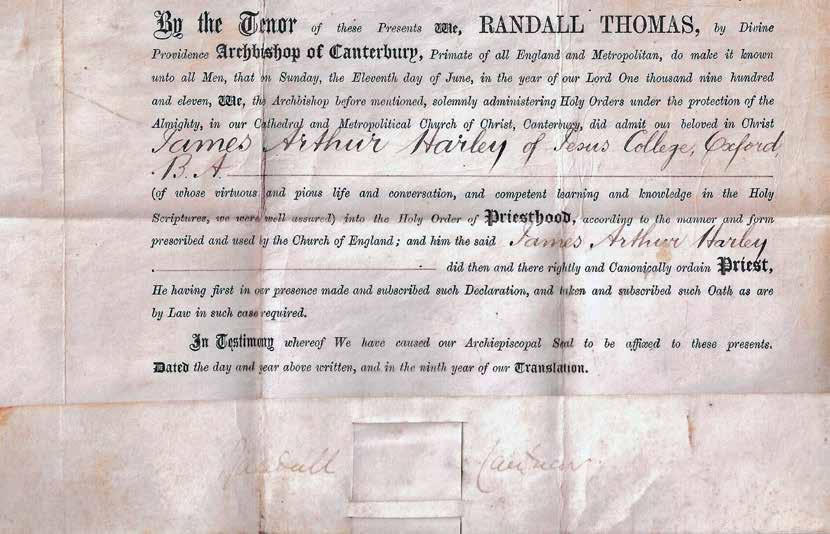

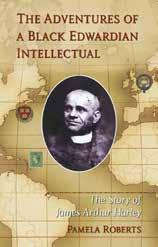

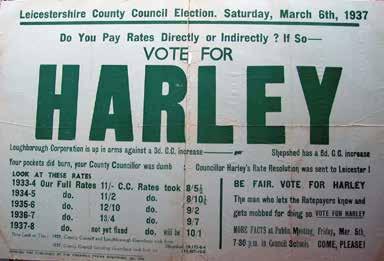

THE ADVENTURES OF A BLACK EDWARDIAN INTELLECTUAL – JAMES ARTHUR HARLEY

TWO WOMEN: BOTH WITH A PASSION TO COMMEMORATE GLOBAL AFRICAN CONTRIBUTIONS By Kwaku

198 CONTEMPORARY ARTS & LEARNING

MAYA ANGELOU: POET, AUTHOR, CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST

YOUR SILENCE WILL NOT PROTECT YOU – AUDRE LORDE

ASSISTANT: Mo Sadegh PRESS & PR: Richard Hillgrove, 6 Hillgrove PR DESIGNED BY: Vivienne Brar ADVERTISING: Ayana Hussein

Thomas

Ross

Burrell

THANKS TO: Stephen Bourne, The Royal British Legion, Mike Bridge, Cherron Inko-Tariah MBE, The RAF, Bishop Grosseteste University and all our contributors, supporters and advertisers. www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk

14 36 54 8 4

12

14

20

22

24

32

42

44

45

46

48

52

54

56

58

60

63

64

66

68

70

72

74

PRODUCTION

SPECIAL

PUBLISHERS: Ian

EDITOR: Catherine

MANAGING EDITOR: Lynda

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR: Kwaku PRODUCTION MANAGER: David Ruiz

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 TIME FOR CHANGE –ACTION NOT WORDS

What a great month for British History! The telling and re-telling of the Black presence in the UK has traditionally covered historical periods way back in time but the immediate past has lots of reasons to commend it as a period full of stories and lessons for Black people that will affect them in the coming decades.

Black History Month is a great time to engage in adventures in learning and for adventures in physical activity. Here are some things to consider, but as you get involved in them, encourage others to join with you. The magazine and website has a lot of articles that point out the need for allies in the workplace and in many other aspects of life. It reminds that steps need to be taken to achieve the change we want to see. Some great examples have been offered by a range of contributors to this issue, sports persons, entertainers, educators, and businesspersons that will help elevate Black people working together and with allies.

This Black History Month also, why not take the opportunity to update yourself on aspects of history and tradition that are becoming more important in the Black community, such things as Nine Nights, the Caribbean wake and the funeral service. Aspects of this celebration of life, an important part of Caribbean culture, are being adopted by other cultures. Things like collecting stories of the contribution of the person to the community helps everyone in appreciating and recognising the contributions of individuals to people and places in the UK. Sometimes it’s the little things people do that have made a difference to individual lives, that have helped unify communities and have just shown that being neighbourly matters. The recent pandemic and the extreme hot weather being experienced this year are challenging communities to look out for and to look after its members.

Learning about Caribbean funeral traditions has become increasingly important to 21st century life as many people of Caribbean descent are forming family units and friendships with others

By Catherine Ross Editor of Black History Month Founder Director, Museumand –The National Caribbean Heritage Museum

who are not of their ethnic group. In dual heritage associations it is such a friendly and loving thing to know things that are important to do, say, and provide when the time comes to saying goodbye. Many of the families who lost friends or family during the pandemic period are still having memorial services, and as those of Caribbean descent come together to do so to acknowledge and celebrate lives, many recall the Caribbean saying often heard at such events, ‘the world has lost a library of valuable experience’.

During the pandemic and since, the issue of Black people not receiving the quality of care, they should expect from the NHS is causing frustration and anger in the community and an increasing number of calls for urgent action to prevent escalating numbers of serious neglect and deaths.

Black people have been battling with such illnesses as sickle cell anaemia, diabetes, cancer, and cardio-vascular diseases and though there are a number of charities and alternative and complementary medicinal methods for dealing with many of these, this Black History Month why not try some of the things that Caribbeans have used from their African traditions. Caribbeans have been drinking ‘bush teas’ for generations

and now many are available in convenient tea bag form or as leaf-blends so there’s none of the need to pick the bush and boil as Caribbeans did ‘back in da day’!! So now we can enjoy an occasional drink of Cerassee or my personal favourite Hibiscus tea daily! Our body’s internal systems will be all the better for it but do check with your doctor if you are being treated for underlying health issues.

Other things we need to be indulging in now that are readily available in supermarkets and stores are the beauty, skin and hair products that Caribbeans have used for generations – aloe vera, cocoa and coconut. These natural and now essential ingredients in commercially produced products mean Caribbeans don’t have to pound, grate, and peel these products, activities not always easy and can often be time consuming. We’ve been using them for generations, they have added to our melanin-rich skin, and as recognised now, darker skin people age more slowly and our skin has a natural glow that have made other cultures warm to and are regular users of what they once called primitive preparations.

On the subject of health, why not add walking to the list of Black History Month adventures. As you walk take time to experience the sights and sounds of the country that Black ancestors have helped build. Probably for the first time enjoy the aspects of history you may not have done before or visit other cities, places or spaces to see where Black people have made a mark. Learning history while improving your health is a great combination activity during a great season of Autumn.

This Black History Month engage in some culinary adventures as well, try food in restaurants, take aways, and from Street Food vendors. However, nothing beats the tradition of being taught at home by a Caribbean elder, so if you are lucky to have one in your family, or you have a friend or neighbour who is from the Caribbean, great, you’re in for a treat. Why not call your time together. ‘Try then Taste’, or ‘Laugh and Learn’, or something fun, as it’s sure to be so…!

Happy Black History Month, a great Time for Change – Action not words!

4 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

black

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 5 6789 P r o s t a t e C a n c e r U K s a r e g s t e r e d c h a r t y n E ng l a n d a n d W a l e s ( 1 0 0 5 5 4 1 ) a n d n S c o t l a n d ( S C 0 3 93 3 2 ) R e g is t e r e d c om p a n y 0 2 6 5 3 8 8 7 Early diagnosis saves lives. Check your risk of prostate cancer in 30 seconds prostatecanceruk.org/bhm-check 1 in 4

men get prostate cancer.

DVSA – Why not join us for a lifetime of safe driving?

The Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA) is part of the wider civil service and our remit, as part of the Department for Transport, is to keep Britain’s roads safe.

DVSA carry out driving tests, approve people to be driving instructors and MOT testers, carry out tests to make sure HGVs and buses are safe to drive, carry out roadside checks and monitor vehicle recalls.

DVSA are committed to race equality and being an inclusive employer. DVSA offers a wide range of roles, including apprenticeships across leadership and management, legal, finance, digital, policy, commercial, HR and operational delivery. DVSA apprenticeships are a blend of formal training and on-the-job experience.

If you would like to find out more about working for DVSA and apprenticeships, scan the QR code below. DVSA actively welcome applications from candidates from diverse backgrounds.

Right: A group of DVSA’s Vehicle Standard Assessor Apprentices (VSA’s) celebrating their achievements and successes. Chris Goble a newly qualified Vehicle Standards Assessor (VSA), explains what his apprenticeship means to him: “Joining DVSA as an apprenticeship was daunting at first but I soon settled in and was made to feel very welcome. I have learned so much in my apprenticeship and thank my colleagues for their help and support. I am excited for my future career at DVSA.’’

Below: Stephanie Ezechukwu, Head of Prosecution and Quality, also reflects on her time working for DVSA: “Since joining DVSA in 2021, I have met some amazing colleagues and have been able to make impactful contributions to improve the Agency. I lead a diverse and growing team, so it is really important to me that I am able to develop myself and others.”

Stephanie Ezechukwu, DVSA Head of Prosecution at work in the DVSA

Bring your whole self to work

Bring your whole self to work

Bring your whole self to work

At DVSA, you’ll be part of an innovative organisation that invests in all our people, ensuring we have the diverse skills to help keep everyone safe on Britain’s roads.

At DVSA, you’ll be part of an innovative organisation that invests in all our people, ensuring we have the diverse skills to help keep everyone safe on Britain’s roads.

At DVSA, you’ll be part of an innovative organisation that invests in all our people, ensuring we have the diverse skills to help keep everyone safe on Britain’s roads.

We support and develop our staff. Our passion for diversity and equality helps us create a positive working culture for all.

We support and develop our staff. Our passion for diversity and equality helps us create a positive working culture for all.

We support and develop our staff. Our passion for diversity and equality helps us create a positive working culture for all.

We’re friendly, welcoming and respectful, with lots of opportunities for your professional and personal development.

We’re friendly, welcoming and respectful, with lots of opportunities for your professional and personal development.

We’re friendly, welcoming and respectful, with lots of opportunities for your professional and personal development.

Search for our latest jobs at

Search for our latest jobs at https://careers.dft.gov.uk/

Search for our latest jobs at

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 7

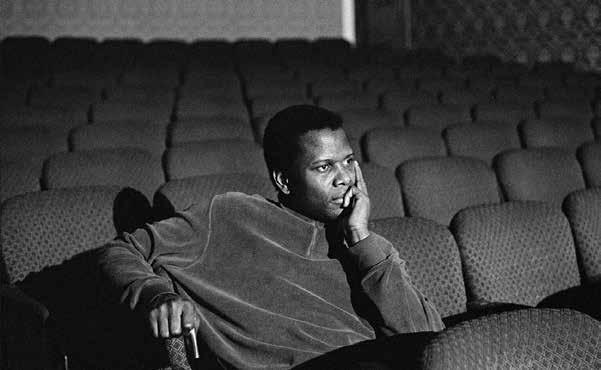

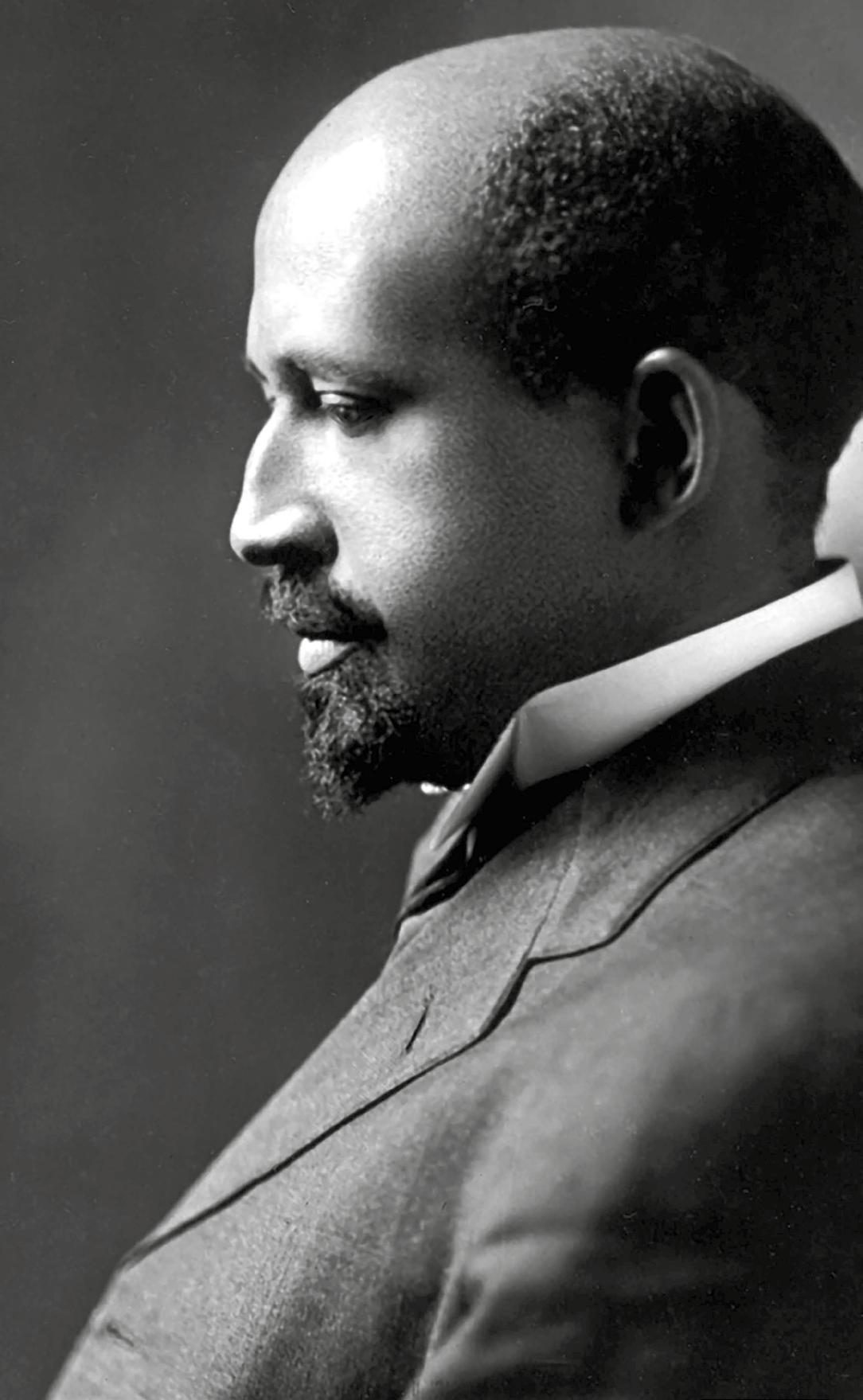

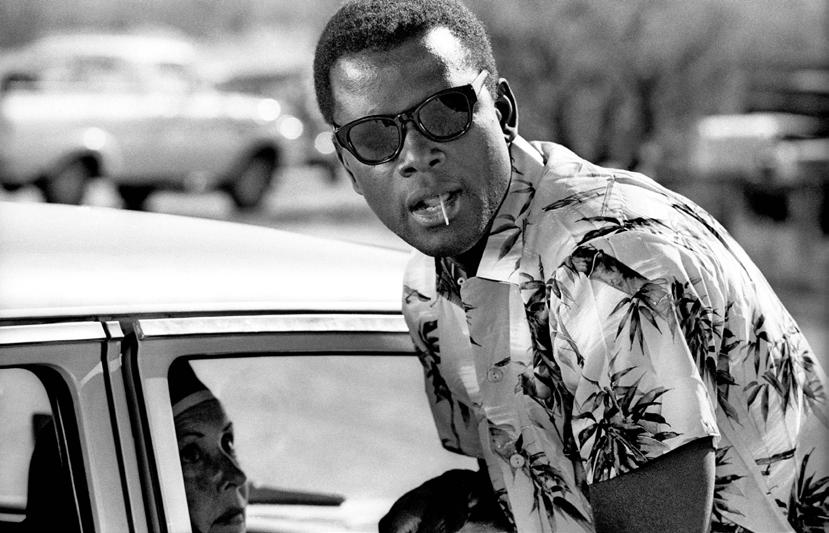

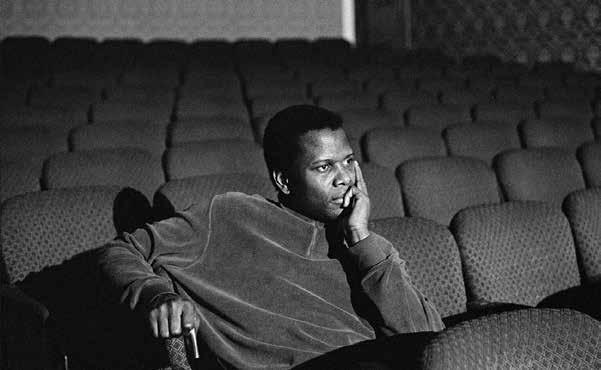

Sidney Poitier actor, director, diplomat, committed activist, and legend

Sidney Poitier will be perhaps best remembered as the first Black actor to win the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Sidney Poitier KBE who died aged 94 on 6 January 2022, was a Bahamian and American actor, film director, and diplomat.

Back in 1964, he was in the headlines becoming the first Black actor and the first Bahamian to win an Academy Award for Best Actor.

And apart from a highly successful film career as a movie star and director, he will also be remembered as a fine diplomat.

Sidney Poitier 1927–2022

We at Black History Month celebrate the life and career of Sidney Poitier who rose along the civil rights movement to become one of America’s leading stars and icons. Poitier was born prematurely in the United States while his parents were visiting from The Bahamas.

While some references give his birth year as 1924, most sources, including Poitier himself, indicate that he was born in 1927.

He grew up on Cat Island, Bahamas, and returned as a teenager to the United States, where he enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II and served a brief stint in a medical unit.

Upon his discharge, he applied to the

American Negro Theatre (ANT) in New York City. Refused a place because of his accent, he practiced American enunciation while listening to the accents of radio voices and reapplied to ANT six months later.

This time he was accepted, and he began studying acting while appearing in a series of ANT productions.

A long-acting career

In 1946 he made his Broadway debut in Lysistrata.

Poitier’s first credited film role was Dr. Luther Brooks, a Black doctor who treats a bigoted white criminal, in No Way Out (1950). The movie established a significant pattern both for Poitier himself and for the Black actors who followed him.

Poitier pushed the restrictive boundaries set by Hollywood and made inroads into the American mainstream.

Although he had a budding film career, Poitier continued to perform in live theatre and won critical acclaim on Broadway in 1959 with his starring role in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. He also starred in the 1961 film adaptation of the drama.

In The Defiant Ones (1958), Poitier was cast as a prisoner who escapes with a white inmate (Tony Curtis); the two must overcome their racial prejudices in order to elude the police.

The film, which was considered

provocative at the time because of its call for racial harmony, earned Poitier an Oscar nomination for best actor; he became the first African American male performer to earn a nod in the lead category.

He also earned acclaim for his work in Porgy and Bess (1959); he portrayed the disabled Porgy, who loves Bess (Dorothy Dandridge), a drug addict being pursued by a number of suitors.

Poitier made history as Homer Smith, an ex-GI who helps nuns build a chapel in Lilies of the Field (1963). His Academy Award win marked the first time a competitive Oscar had been awarded to an African American male.

Poitier was also just the second Black actor to win an Academy Award (Hattie McDaniel had won a best supporting actress Oscar for Gone with the Wind [1939] but he was the first black actor to grab Best Actor.

Poitier starred in a series of acclaimed films. In To Sir, with Love (1967), he portrayed a charismatic schoolteacher who earns the respect of his students at an inner-city school. Next was In the Heat of the Night (1967), a crime drama that focused on the uneasy partnership that develops between a bigoted white Southern police chief (played by Rod Steiger) and Virgil Tibbs, an intellectual Black Philadelphia detective (Poitier). The film received the Oscar for best picture.

8 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

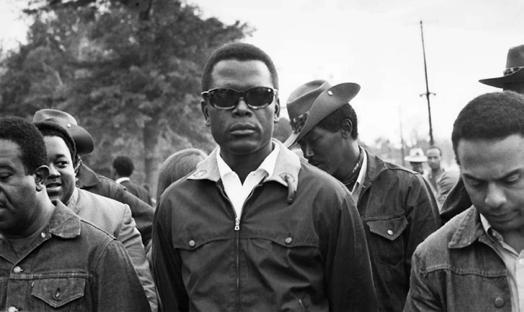

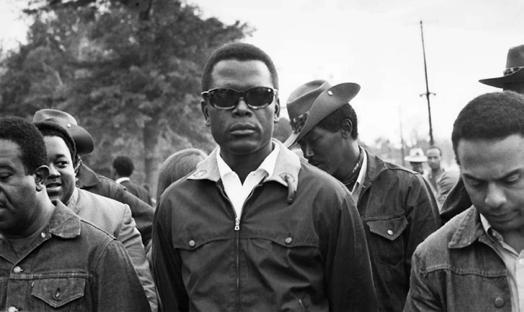

Opposite: Lilies of the Field; Clockwise from left: A Raisin in the Sun, 1959, with Louis Gossett, Jr. and Ruby Dee; Sidney Poitier, centre supporting the Poor People’s Campaign at Resurrection City, a shantytown set up by protesters in Washington, D.C., in May 1968.

Poitier’s other movie from 1967 was Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, in which he portrayed the fiancé of a white woman (Katharine Houghton) who takes him home to meet her liberal parents (Spencer Tracy, in his last film, and Katharine Hepburn). The success of the movies made Poitier the top box-office draw of the year.

Often cast playing determined, unflinching heroes, he also redefined roles for African Americans by rejecting parts that were based on racial stereotypes.

Out of such an extensive list of movies, perhaps his most revered films include Lillies on the Field (he won the Best Actor Oscar, a first for Black artists), Best Picture for In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and Sneakers

In the movie Mandela and de Klerk (1997) – Poitier portrayed Mandela and co-starred with Michael Caine, who played former South African President F.W. de Klerk, in a story that depicted Mandela’s release from Robben Island and the transition of power between the two men. Poitier was also a director In 1972 Poitier made his directorial debut with Buck and the Preacher, an amiable western in which he played a con-man preacher; his costars were Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee.

His early directorial movies were not a success, however the comedy Uptown

Saturday Night (1974) was an enormous hit, thanks to the chemistry between Poitier and costars Bill Cosby and Belafonte.

Poitier then reteamed with Cosby on Let’s Do It Again (1975) and A Piece of the Action (1977).

Off Screen achievements

Not only was his film career legendary but many will also remember Sidney Poitier for his off-screen achievements as well.

He was an unparalleled actor, a committed activist, and a beloved family member.

He played a visible role in the civil rights movement, marching alongside protesters at Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington in 1963 and traveling the South with fellow activist and actor Harry Belafonte.

A dual citizen of the United States and The Bahamas, he served as ambassador to Japan for The Bahamas from 1997 to 2007.

In 2009 he was awarded the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Poitier chronicled his experiences in This Life (1980) and The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (2000). Life Beyond Measure: Letters to My GreatGranddaughter (2008) was a volume of advice and insights in epistolary form. He also released a suspense novel, Montaro Caine, in 2013.

Perhaps the most important life

lessons he imparted in his autobiography came from his father. “Of all his teachings, the most enduring was the one about the true measure of a man,” Poitier wrote.

“That true measure was how well he provided for his children, and it stuck with me as if it were etched in my brain.”

Many awards and honours

Poitier received several honors and awards during his lifetime. These included a Grammy Award, two Golden Globe Awards, and a British Academy Film Award.

Poitier also received numerous honours during his lifetime including the Academy Honorary Award for his lifetime achievement in film in 2001.

In 1992, he received the AFI Life Achievement Award and two years later received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

In 1981, he received the Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award and in 2016 he received the BAFTA Fellowship.

In 1995, Poitier received the Kennedy Center Honor.

However perhaps the two most meaningful awards were being the Knighthood awarded to him by H. M. Queen Elizabeth II in 1968 and The Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States of America’s highest civilian honour, awarded to him by President Barack Obama in 2009.

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 9

I am extremely proud the be the Head of Diversity and Inclusion Reform within the Home Office.

The Home Office is one of the great departments of state with a wide-ranging remit. For me, the essence of our work is around security and safety. That means reducing crime, safeguarding people who may be vulnerable, as an example preventing violence against women and girls. The Home Office is also responsible for policing and immigration, as well as issuing passports. The work we do touches on the lives of many.

To do this well it is essential that the Home Office reflects 21st century Britain, being representative of the communities we serve and the people we come into contact with. That means being accountable for our actions and being truly inclusive in all we do. We must be an organisation that improves the lived experience of all colleagues, whatever their background. My team have a variety of different personal experiences and perspectives. At the heart of our way of working is respect for each other, listening to each other, and seeing how we continue to improve further the experience of our colleagues and citizens.

When I chose to join the Home Office it was because I was keen to be part of the diverse nature of our work which affects every citizen as well as all those who enter the United Kingdom. Next year marks a special milestone for me, as I will have worked in the Home Office for 30 years and in that time seen 13 different Home Secretaries, starting with Ken Clarke and this week welcoming Suella Braverman.

Back in the 1990s I originally joined as an Administrative Assistant, the most junior grade in the Civil Service. My personal experience of working at all levels across the Home Office up to Director level has shaped how I lead. Giving others the opportunities I had is a real responsibility and helping everyone regardless of background to reach their potential.

I was fortunate to be given the opportunity to learn, grow and specialise in a profession; in my case programme and project delivery and being supported to gain qualifications in Business Architecture. That is not an uncommon experience in the Home Office, where investing in our people and their professional development is a key focus for us. This helped me to work in multiple departments over the years in high-profile positions. I led the Greater London Estate Consolidation Programme, and then multiple projects in our major airports. No free flights, but really exciting and valuable work! More recently that’s meant being in the thick of it, heading up work needed to deliver the EU Exit and the Covid 19 early response. I have held multiple leadership positions driving efficiencies, strategic planning and transformation.

I am extremely proud to now be in a role where I lead cultural transformation spanning 40,000 staff across multiple regions, delivering evidence-led D&I reform based on increased accountability, inclusion, and a commitment to be representative of the communities we serve. I work across a complex matrix of

JOIN

SHARON

HEAD OF DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION REFORM

stakeholders to ensure appropriate success measures, using data as a strategic asset when engaging and influencing staff and citizens.

I have been proud to be a Race Champion and a mentor, coach and sponsor to many, which is incredibly rewarding. My only ask of each person that I mentor is that they make a personal commitment to mentor others – “each one, teach one”. I am passionate about ensuring that every individual feels valued, appreciated, and respected regardless of background.

The Windrush review recommendations have helped to shape our approach to ensure diversity and inclusion is future focussed and recognises the breadth of the diversity landscape. We have made significant progress in becoming a listening and learning organisation. I have seen the department work towards righting the wrongs of Windrush. I am proud to be a Windrush volunteer. Whilst some progress has been made, we still have a long way to go and I know that as a Department, that is something we are committed to. D&I needs to be at the heart of everything we do, and that is a key area which we continue to focus on as we build on our successes.

There are so many opportunities and careers available that I would encourage everyone to look at working in the Home Office to see what we do, how we’ve changed and where we are going.

I would encourage everyone (particularly those from ethnic minorities where we have low representation at Director level) to aim high. I would love to see more Black people at Senior Civil Servant level. Increased diversity and the opportunity to bring your knowledge, skills and experience to make a real difference to our work is invaluable. Being representative of our communities can only help us to understand, deliver and make a difference, with inclusion being at the heart of our delivery.

Every day our teams across the UK and beyond deliver outcomes to improve citizens’ lives. Our work is challenging, high profile and rewarding. To deliver it is a team effort, and we rely on talented people with a wide range of skills and experience. And that’s where you come in: whether your skills lie in customer service or accounting, software engineering or making policy, it’s likely we’ll have a role you’ll be interested in. Your ideas and input will mean so much more working with us, because everyone brings their own insights, background and experiences to our work. And it’s this diversity of thinking that is transforming the way we work – and the work we do.

US Interested in working for us?

You can view further information about our roles at: www.civil-service-careers.gov.uk/departments/working-for-the-home-office/ and scan the QR code for our latest job opportunities. 10 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

1. Why did you choose to join the Home Office?

I joined the Home Office after a long spell in the private sector in a job which took me away from home. Whilst it was nice to travel, I wanted to settle down and have a family. I saw an advert for a position in the Home Office which interested me. I realised that there weren’t many people from my background that worked for the Home Office, so I saw joining as making a positive change.

2. How long have you been in the Home Office? 21 years!

3. What is your day-to-day work like?

Every day is busy, different, and exciting in equal measure. I am a Deputy Chief Caseworker working on the EU Settlement Scheme, dealing with cases involving EU nationals and their relatives who wish to settle here in the UK. The cases vary in complexity and can involve vulnerable applicants, fraudulent applications, minors, and other challenges. I also Chair The NETWORK which is the Home Office’s race staff support group.

4. What do you enjoy most about your job?

I love the variety in my work and the commitment and passion of the people I work with. I love working for an organisation that cares for its staff and although we know we are not perfect; we’re striving to make the Home Office a better place for all staff, so that we can serve the public to the best of our ability. Above all, I most enjoy serving the public in the way that I would like to be served. In my NETWORK role, I really enjoy supporting colleagues, Managers, and the wider Home Office – it’s so rewarding!

5. What has your career journey been?

I wanted to be a lawyer, so trained to be a Barrister and Solicitor and practised law in Nigeria for a few years. On my return to the UK, I worked in the private sector managing contracts for a service delivery company for local authorities. In 2001, I joined the Home Office as an Immigration Officer. I’ve had various roles in the Home Office, including operational delivery, commercial, human resources and policy. I am currently a Deputy Chief Caseworker, a role that I do in parallel with my position as the Chair of the NETWORK.

6. What are the benefits of being in the Home Office?

I love the flexibility as it’s allowed me to have a good work-life balance, which I didn’t always have in the private sector. I’m able to spend time with my family, pursue my hobbies, all whilst making a strong contribution in the workplace. The diversity in the Home Office is comparatively good but we are continuously looking to improve.

7. What would you say to someone considering a career in the Home Office?

The Home Office is a great place to work! Senior managers and colleagues care about staff and take their wellbeing seriously. I always recommend the Home Office to people I meet and especially to those who have never considered a career in the Civil Service. I joined the Home Office despite some negative views within my community, and 20+ years later I am still here and enjoying my work as much as ever!

TEEMA

RACE PROGRAMME LEAD –PUBLIC SAFETY GROUP

1. Why did you choose to join the Home Office?

I saw the Home Office as a dynamic department with interesting policy areas. I was particularly interested in working in policy areas that look to protect the most vulnerable in society, something that I have always been passionate about.

2. How long have you been in the Home Office?

4 years

3. What is your day-to-day work like?

Every day is different but my role is focused on making the Home Office an inclusive and diverse environment for ethnic minorities. I help to ensure that the department is representative at all levels) and that as an organisation we understand the diversity and cultural needs of the public we serve.

4. What do you enjoy most about your job?

I love the fact that I represent so many voices and have a focus of implementing positive cultural change within a dynamic and strategic organisation. I get to work with talented colleagues from across the department and have the privilege of holding senior leaders to account. It’s not easy but when you see the tangible impact of your work, there is no better feeling!

5. What has your career journey been?

Believe it or not after I completed university I set out to be a civil servant. Whilst writing my Masters’ dissertation I was able to get on to the Summer Diversity Internship Programme which gave me the first taste of Civil Service life. I joined the Department of Work and Pensions, working in HR and I loved it. After a short time away, I joined the Civil Service full time at the Department for Education working on free schools (new schools) where I opened 3 brand new schools. After 4 years I decided to pure my interest in protecting vulnerable people in society, so I joined the Home Office as part of the Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Unit. I undertook various roles in the unit including international focused work. In January I moved into a brand new role which focuses on internal race diversity.

6. What are the benefits of being in the Home Office?

The number of talented colleagues that make up the department - there is talent at all levels of the organisation. This has enabled me to develop quickly and become a better civil servant.

7. What would you say to someone considering a career in the Home Office?

Be prepared for hard work, but it will make you a better civil servant! I’ve always had the belief that if you can work in the Home Office and thrive, then you can probably thrive in any other government department.

FASIL THE NETWORK CHAIR

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 11

Clenching my jaw with shackles because the moment I open my mouth you say my english is wack. Can you speak African? No, I only speak black. What is speaking black? Speaking black is making sure that when you’re speaking facts you gotta stay on track before they look at you shoot and attack.

Harriet Tubman came from a shack. Dave helped our generation fight back. Don’t stop me now I’m ready to attack.

My voice is only heard when truth has been stirred. There is music in my melanin, yeah I talk hella black. The memory of slave ships drown my mind. Writing these words to help past the time.

Slavery was abolished that’s what I heard on the news but that’s far from the truth because people like me still remain captive to our skin colour of which none of us can choose.

If you’re black then you can fight. It shouldn’t be a privilege to have skin that is white.

When a black man walks, when a black man talks, where a white man walks. Doesn’t fear follow near. Or so they say. Can you hear the whispers from ear to ear?’’ Black doesn’t crack, it just tears, Now tell me why am I living in fear?

Weeping black mothers tears the same tears that keep graveyard grass green. I hate to see black on black crime. Come on bruv we’re all on the same team. They turn us against each other, they

JEBRIL UMO –MY ANGRY BLACK VOICE

divide us, segregate us. Division is how they win but with unity they will crumble. When you hold those sacred sounds on your tongue do you feel less holy. The monkey sounds.

Hahaha. There goes the monkey. Because to you for some weird reason my skin just looks so funky. Loud in laughter silent in our suffering. Black mothers cries. It was just an inhaler. Cap. That’s all lies. But yet you have no respect for her baby boy’s demise. No matter how hard she tries, no matter how thick her thighs or her lips, her son’s melanin still permits you to aim, fire and shoot. Oh shoot another innocent black man killed. Our execution is still stuck on a painful loop. Police sirens sound like amazing grace being sung at a funeral.

How many more times will I have to hear one of my brothers saying mumma i’m fine. Before I hear his scream collide with the sound of your bullet ricocheting through the air as you shoot. You’re just jealous of our roots. Roots that we don’t know because you kept my ancestors hanging from the necks with their toes stroking the ground. Don’t look away, you can’t turn back now.

Our melanin is like a pirate’s sacred loot.

A war on black boys. Walking down the street to hear the riots roar. No wonder as a child we grew up with toys shaped as guns. From the age of six I had learned my rights that was my definition of fun. Well can you blame us?

Starting up all these laws and curfew to tame us.

I want justice for Breonna Taylor, a young black woman shot dead in her own bed.

You’ve gone from whipping holes in our backs to shooting bullets in our children.

Racism ain’t gone my man it’s just hidden.

I’m so tired of running, I’m out of breath. I’m so tired of being judged before you get to know me. I’m so tired of being at an unfair disadvantage. I’m so tired of being tired. I’m so tired of seeing my uncle fired from his job because you say that his nappy hair makes him look uninspired. All because you see black as undesired. But I am not tired of being black. My black voice may be savage at times but I wouldn’t change it for any privilege in the world.

And that is the truth, the truth all y’all lack.

I’m not tired of being black.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

My name is Jebril Umo. I am a 14 year old black male from south east London. I have always had a passion for writing and it is something that I am good at. Being a young black boy comes with many challenges. However, I always stay resilient to them and I never give up something my mother had taught me from when I was young.

12 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

Everyone

Coca-Cola Europacific Partners (CCEP) is the world’s largest independent Coca-Cola bottler. CCEP GB makes, sells and distributes soft drinks for every occasion and sells more than four billion bottles and cans every year.

At CCEP we have a philosophy that ‘Everyone is Welcome’. This ethos underpins everything we do, creating an environment where everyone is encouraged to ‘Be Yourself, Be Valued, Belong’. We strive to provide opportunities that are open to people from all demographics and backgrounds.

It’s this mantra that means, as a business, we endeavour to challenge the underrepresentation seen in the corporate world. Channelling this mindset when recruiting for those entering the business for the first time is the best place to start.

Having the right mix of talent for our future sustainability is vital – that means working with and fostering talent from all demographics and backgrounds, with a focus on those from black and Asian heritage.

“

would like to see Black people visibly represented at every level of our business, especially in senior leadership roles within the next two years.

With more than 11 million national records within our care, Black History Month 2022 is a vital reminder of our commitment to increasing the use and experience of our collections for more people.

Our collections span 1,000 years of difference, debate and progress. Created from the perspective of state and empire, we hold important records that bear witness to past injustice, and the long and continued fight for racial equality.

We are proud to play our part in finding greater ways to make these significant records more accessible.

Archives are for everyone because they are about everyone –past, present and future

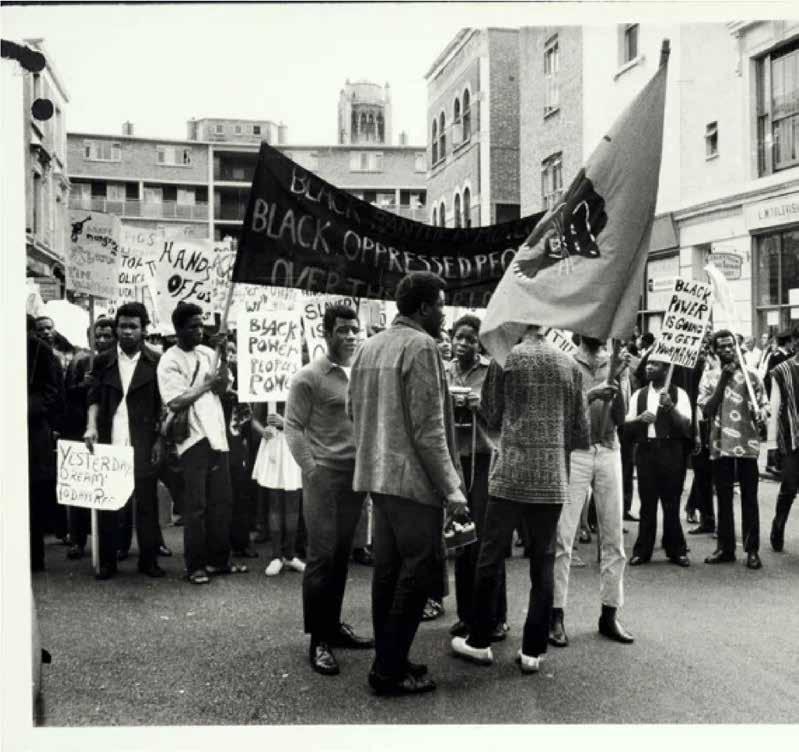

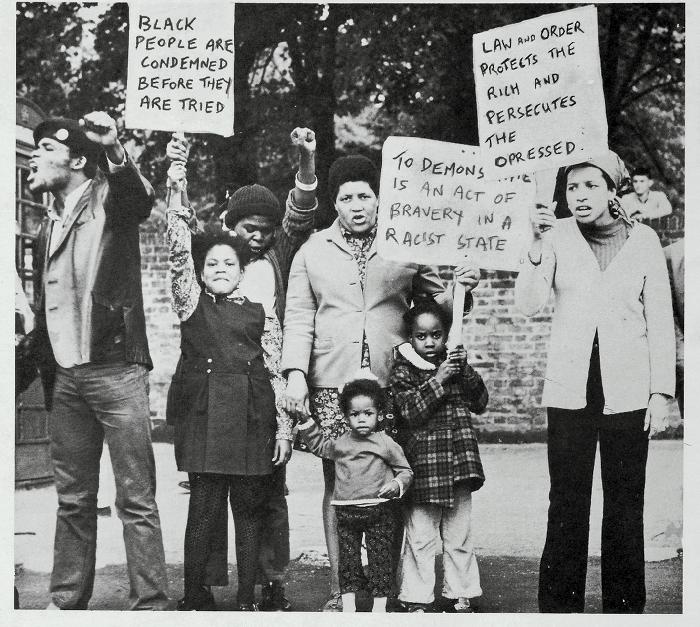

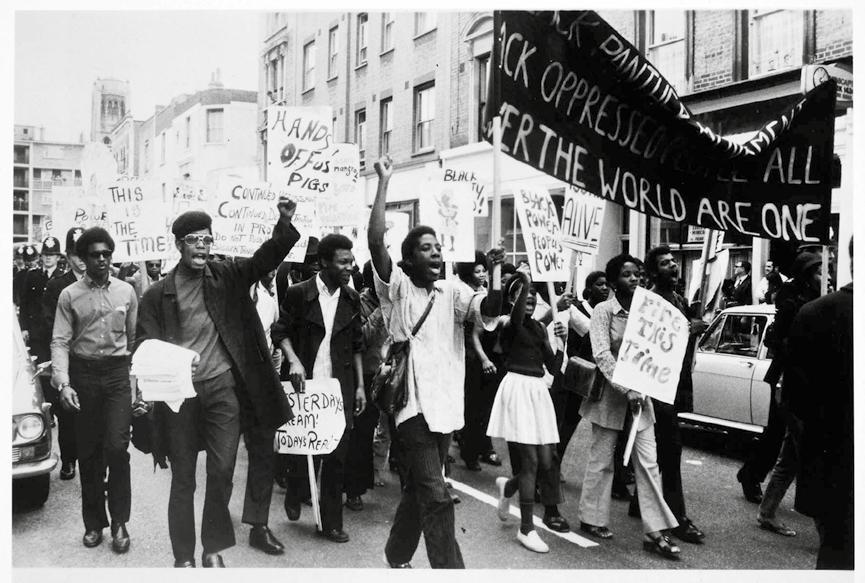

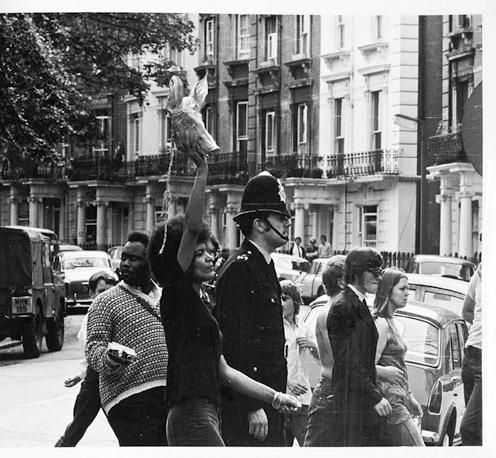

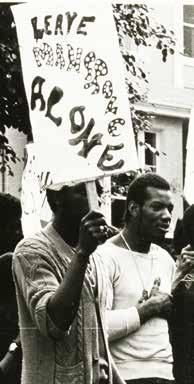

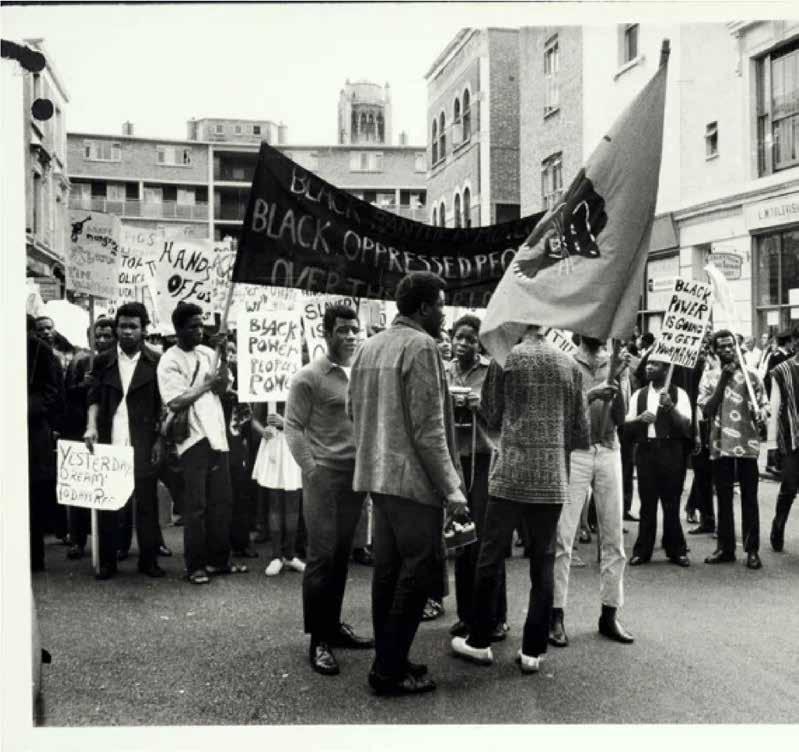

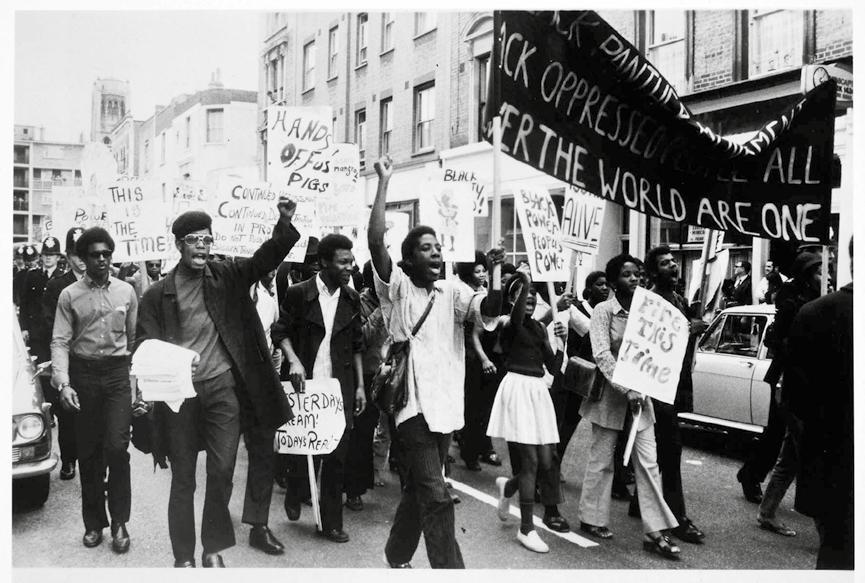

Find our Black British history resources at nationalarchives.gov.uk/black-history Black Power demonstration and march, Notting Hill, 1970catalogue reference MEPO 31/21 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 13

is welcome

I

” Lou Cenac Senior Manager, People & Culture Business Partner COC1541_Everyones Welcome Advertorial_188x133mm_AW2.indd 1 19/08/2022 17:25

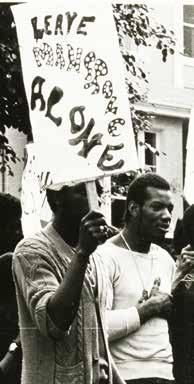

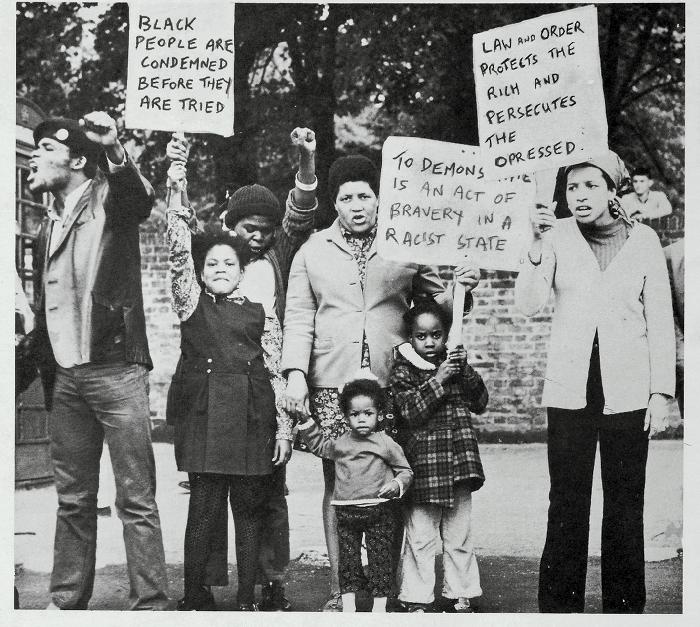

Civil Rights Movement in Britaina poverty of knowledge?

The Civil Rights Movement is emotively charged by historical profound moments and figures.

But as an immediate thought does Civil Rights conjure images of Britain’s own Civil Rights movement to you?

For me (and perhaps you) there are varying images of immense magnitude.

The Klu Klux Klan (KKK) standing over a black victim, Martin Luther King rallying people to protest in peace, Malcolm X rallying people to protest “by any means necessary”, Claudette Covin and then Rosa Parks, churches burning, crosses burning, heavy handed police, Black Panthers, or the gruesome date of August 7, 1930, where a baying mob of thousands in Marion Indiana lynch two men. The stark image of thousands of men, women and children gleefully staring at the camera emboldened by their cowardly lynching of these two men is chilling.

14 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

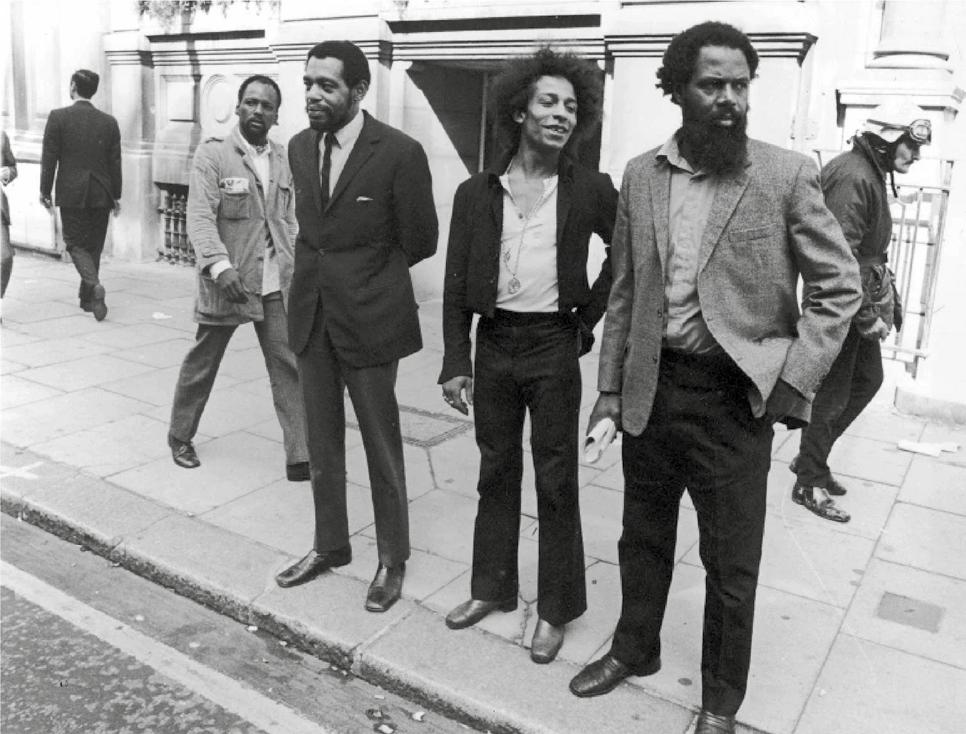

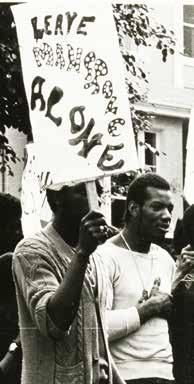

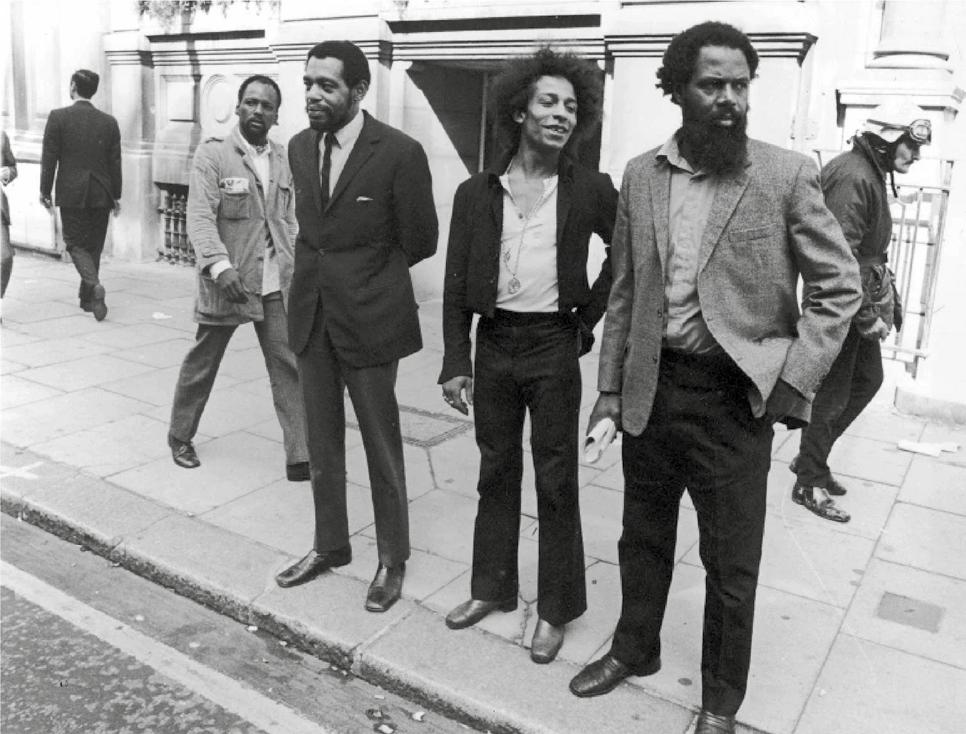

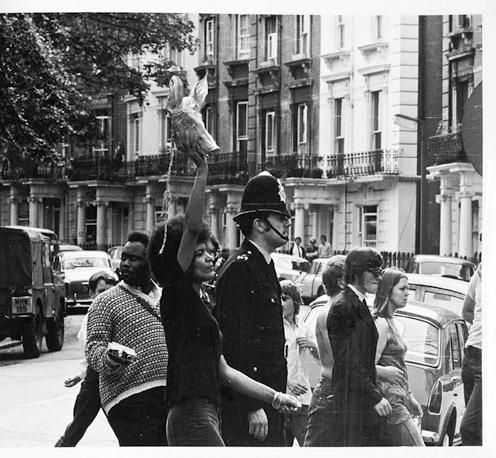

Black Panther Movement at the Mangrove demonstration in 1970

The images are endless, graphic, disturbing, fuelling outrage, sadness, dis-belief, confusion and more.

But these images are distinctly American. Civil Rights Movement and America seamlessly go hand in hand.

There is (to a degree) this incongruous, paradoxical romanticisation of the movement and America. Black American people (and whites too) standing up for Black Civil Rights.

In this strange, perhaps slightly macabre emotion I almost want to be there in the 60’s Deep South standing in unison with my brothers and sisters in this hugely dangerous period. It was a time where blacks had to fight to be humanised.

But there was a powerful Civil Rights

KEY BRITISH CIVIL RIGHTS EVENTS

1919 Uprisings in London, Cardiff and Liverpool

1931 Dr Harold Moody establishes the League of Coloured Peoples

1948 British Nationality Act; SS Empire Windrush arrives at Tilbury

1958 Uprisings in London and Nottingham

1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act

1958–1966 Notting Hill Carnival begins (exact date is disputed)

1963 Bristol bus boycott

1965, 1968, 1975 Race Relations Acts

Movement within UK. For me and maybe for other Black British people there is a poverty of knowledge regarding our own movement.

Partly that is due to the ‘American Imperialism’ (if you will) through Western global media (as a whole) on the ideology and ‘ownership’ of ‘Civil Rights Movement’.

Indeed it is fair to say that in many ways popular British media have (to an extent) had a distinct bias to that Americanism of the Civil Rights Movement. This bias has been to the detriment of the British black movement.

There have been some telling British films – think the powerful SUS (2010) starring Clint Dyer. More recently, the talented Sir Steve McQueen directed the

1967 British Black Panther party established

1970 Trial of the Mangrove Nine

1979 Royal Commission on Criminal Procedure (led to repeal of the ‘Sus laws’)

1981 Brixton uprisings and Lord Scarman report

1999 Macpherson Report published following the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry

2011 Riots following the shooting by police of Mark Duggan

telling series Small Axe (2020) examining three events from 1981 – in January, the New Cross Fire which killed 13 black teenagers, March, Black People’s Day of Action, which saw more than 20,000 people join the first organised mass protest by black British people: and the Brixton riots in April. I think there is a poverty of such powerful historical British Civil Rights work.

Perhaps more damningly and maybe harder to digest is an idea.

As blacks (individually) within the UK we are complicit to this poverty of knowledge, regarding our own Civil Rights Movement. We have to a degree been sucked into an inertia of sorts where we do not really push in a concerted, sustained,

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 15

and holistic manner for knowledge regarding the UK Civil Rights movement.

I would strongly argue that an American child today has a deeper, more knowledgeable understanding of the American Civil Rights Movement than a British child would of our own movement.

How many British children could name important events within our Black British history? Or how many could name significant figures? They could however reel off a list of American Civil Rights moments or figures. Or more significant reel off just exactly who Winston Churchill and his importance to the ‘world’ (despite his own racist attitudes) some 60 years after his death.

This is nothing to do with the fact that

perhaps the American Civil Rights Movement was somehow more profound than ours. That is if we want to play the unsavoury game ‘my Civil Rights Movement is better than yours’.

No, the answer to why our movement continues with this poverty will surely be multi-faceted.

For me however as I write this piece, I am conscious of the fact that I have to be careful that I do not come across as speaking for everyone. Not everyone has a ‘poverty of knowledge’.

I am sure there are those reading this who have a deep knowledge of our own movement. That knowledge in turn they have abundantly blessed their children with. I can vividly see the collective raising

of eyebrows at my assertions.

Hopefully to quell your thoughts or criticism of me.

On a personal level I am acutely aware of my inadequacies as a Black British male suffering from a ‘poverty of knowledge’.

I am ashamed in many ways that maybe here I am writing this piece on our movement when I am sure that my poverty of knowledge is shocking.

I know Black History month, the Brixton Riots, Tottenham Riots, Mary Seacole, names like Bernie Grant, Darcus Howe, (despite what people might say) the influential Diana Abbot and more.

But Sir Steve McQueen’s series was particularly telling for me. It showed me how much I did not know. How superficial

Mangrove Nine protest

On 9 August 1970, a group of Black Power activists led 150 people on a march against police harassment of the black community in Notting Hill, London. They called for the ‘end of the persecution of the Mangrove Restaurant’. Between January 1969 and July 1970, the police had raided the Mangrove Restaurant twelves times. No evidence of illegal activity was found during these raids.

Local Police Constable Frank Pulley remained convinced that the restaurant was ‘a den of iniquity’ frequented by ‘pimps, prostitutes and criminals’. At the 1970 march in defence of the

Mangrove, violence broke out between the police and protestors.

The following year nine men and women were put on trial at the Old Bailey for causing a riot at the march. Their names were Darcus Howe, Frank Crichlow, Rhodan Gordan, Althea JonesLacointe, Barbara Beese, Godfrey Miller, Rupert Glasgow Boyce, Anthony Carlisle Innis and Rothwell Kentish. These men and women became known nationally as the ‘Mangrove Nine.’ When all nine defendants were acquitted of the most serious charges after a long 55-day trial, it was widely recognised as a moment of victory for black protest.

16 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

The owners of the Mangrove restaurant after their court appearance at Kensington Petty Sessions on 15 August 1970.

my knowledge was? How little I invested my time to teach my own children the knowledge regarding the history of Blacks in the UK. How my own poverty of knowledge of the British Civil Rights movement was in fact self-induced due to complacency.

From names who died like Cynthia Jarret (a catalyst for the Broadwater Farm Riots 1985), Derek Bennett, Joy Gardener, and Mark Duggan (and the 2011 UK wide riots that followed his death).

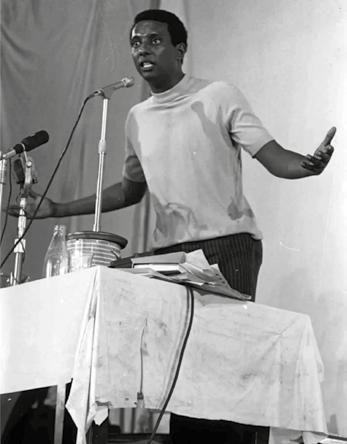

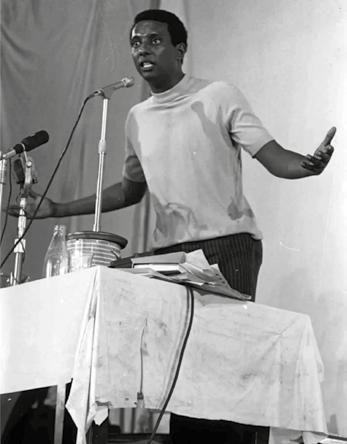

To pivotal moments-think 1967 when American activist and leader of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) spoke at a gathering in Camden. He inspired black people living in Britain to ‘organise

against prejudice and white power’.

My knowledge was and is merely the proverbial ‘tip of an iceberg’. I know dates.

I know names. I know moments of time.

As is always the case things/changes need to start with the individual and for our children at home.

It is not a poverty of knowledge but rather (in may case it seems) a poverty of pushing my own access to that knowledge and then imparting this knowledge to my children. Thankfully, my children are consciously individual.

It is a telling, and painful realisation that my own inertia and ‘poverty of knowledge’ must be addressed.

By Semper Azeez-Harris

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 17

Kwame Ture

WANTED: Effective Allies Who Take Meaningful Actions

I don’t want you to just dress like me, but to call out behaviours that hurt, harm, and hamper my progress at work.

I don’t want you to just speak like me, but to speak up for me when policies and procedures block my progress, and for other Black people who can’t or don’t get seen or heard.

I don’t want you to just live near me, but to oppose the gentrification that destroys our long-established neighbourhoods and our communities.

I don’t want you to just eat Caribbean food, but to support other Black businesses and enterprises, and the communities behind them.

I don’t want you to just listen to Black music, but to listen to, appreciate and recognise those that created it and be an ally to their communities.

I don’t want you to just decolonise the curriculum, but to employ more Black educators and support staff and embed Black history into the curriculum.

I don’t want you to just celebrate Windrush Day and Black History Month, but to challenge inequalities all year round and recognise the power and potential of equality, diversity, and inclusion to create stronger teams, new ways of working and more successful organisations.

I don’t want you to just accept me and be your ‘black friend’, but to be an ally to other Black people and listen to their experiences and opinions, because I don’t represent or speak for all Black people.

I don’t want you to just acknowledge white privilege, but to use the platforms you have to take action and enable a marginalised individual or group to progress, thrive and fully contribute.

I don’t want you to just take nominal steps to improve the status quo by using me as a token Black presence, but to open doors to other marginalised groups and become a more equal, diverse, and inclusive workplace.

I don’t want you to just open up opportunities for change and then leave me to fix things on my own, but for us to work together to find solutions and make our workplace the best it can be for everyone.

I don’t want you to just talk about and enjoy the fun stuff about my culture, but to have some real conversations and get to know the real me, including my ambitions, my concerns, and my potential. My culture offers far more than music, sport, dance, and food – for me and for you.

I want you to know that as an ally, you will be privy to and enjoy rich cultural resources and share the benefits of achievements and contributions that are still being revealed, and those yet to come, still waiting to be discovered. There is a Caribbean saying that perfectly describes the need to work together and support one another’s self-realisation for the benefit of society as a whole… “Today for you, tomorrow for me!”

By Lynda Burrell

18 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

CHANGE … TIME FOR

HP

Every year we welcome a community of interns with great minds, and this year is no different. At HP, interns are our future leaders, a place where they can follow in the footsteps of our CEO, Enrique Lores, who began his HP journey 30 years ago as an intern.

At the heart of our company is diversity, equity and inclusion. They strengthen our culture, unite our teams and inspire new forms of progress in our communities. The benefit of working with a diverse team and creating opportunities for mentorship at HP will have a lasting effect on your career.

A HP internship will enable you to work on projects that have real lasting impact.

Join our group of diverse thinkers and start your career.

Applications start Autumn

As an intern at HP, you will have

Make a difference

We ensure our interns have substantial projects that make a lasting impact even after they’ve left HP.

Meet people

You will be encouraged to network with team members, stakeholders, and leaders to build

that last a lifetime.

Grow your skills

Whether it be a personal branding workshop or an

grow

finance,

person

host

as

2022

Internships

connections

introduction to

we

a variety of events to help you

as a

and

an employee.

an opportunity to… Apply now jobs.hp.com/students-graduates/?job_ type[]=Apprenticeship&job_type[]=Graduate&job_ type[]=Internship BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 19

SCRATCHYLUS

For example, The Colour Bar, it was a crime for Black people to learn to read and write, restriction of movement, work without pay.

Thank goodness for people of colour that came along like Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Malcolm X, John Hendrich Clarke, Rastafari, Emperor Haile Selassie among others who came along and reminded these people of their great Ancestry, History, and the greatness they have achieved and can carry on achieving.

Many organisations were born from this new awakening.

Can you explain how allies are important and their role.

Just like any other organisation representing Justice, the people who are at the forefront of the oppression must be at the forefront of the strive for justice, always with the attitude that if someone proposes to help with and facilitate their cause they shouldn’t dismiss with ego and arrogance they should always exercise grace and due diligence in order to achieve the aims and objectives.

What message do you have for our readers?

As a person that has many reasons to be optimistic about mankind and womankind despite all the suffering and woes of the world Resetting The Mindset’ is key to real change. Big up the people working for others despite the constraints.

As I say The Healing:

‘’ It will be sunny again, it was cloudy then but soon we will be ready to rise,

Looking good feeling good focused on the prize,

We caught up with Scratchylus to talk about this year’s theme for Black History Month 2022; ‘Time For Change Action Not Words #ResetTheMindset’ and hear what he has to say about how real change can be achieved by Resetting our Mindsets

What does ‘Reset The Mindset’ mean to you. Scratchylus: First of all I would love to extend my love and gratitude to all those who have a healing spirit, mood and attitude in these very challenging times, more Love Comfort and Guidance always.

In order to Reset The Mindset we have to have the capacity to heal which takes empathy, overstanding and most importantly not being in denial. We have to rid ourselves of false perceptions, harmful agendas, ignorance and arrogance and replace it with kindness for one another, encouragement, grace, gratitude and respect for your fellow human beings.

The aspiration for change of mindset and understanding injustices seems to be gathering pace in recent years. This has been highlighted by the death of George Floyd, The Windrush Scandal and the negligence that led to Grenfell. From my personal experience although society seems to have become more politically divided it has come together more spiritually. Naturally this is largely to do with the increased interaction between our communities which has laid the ground for tolerance empathy and ultimately healing.

Can you expand on why society over the last 2000 years has been taught largely about slavery, and why there is a lack of understanding regarding Black people’s heritage.

Society over the last 2000 years has been deliberately Institutionalised by the slave masters and their colleagues in order to maintain their wealth and privilege. In order to get everyone on board they had to create negative narratives, negative stereo types along with racist laws and practises to keep the status quo.

After all the pain there’s been the pain we’ve seen and after all that’s said and done,

It’s time to put a smile on their face. It’s time to have some fun.

Scratchylus is an Award Winning International Artist whose mission is to Reset The Mindset , educate , uplift, enlighten and empower through Word Sound and Power. The messages in his music provoke thought and inspire us to do our best work and be our best self.

Scratchylus will be touring Universities Colleges and public and private organisations with his positive uplifting and educational messages as part of the ‘Reset The Mindset: The Healing Tour’.

Please do get on board with this important tour .

For further information about the tour and bookings contact: ukuniversitytourbhm@gmail.com

For more info on Scratchylus reverbnation/scratchylus

20 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

Resetting The Mindset Healing a Fractured Society In These Very Challenging Times CHANGE … TIME FOR

and Plumbing & Heating

IS ALWAYS WITH YOU. A TRADE Electrical

Apprenticeships If you’re leaving school or college this year and you’re worried about the cost of university and finding a good job afterwards, a JTL apprenticeship could be a better option for you. With a JTL apprenticeship you can launch a rewarding lifelong career as an electrician or a plumbing & heating engineer, and once fully qualified you can go on to earn an annual salary of £32k or more. Get your career in the trades started today: jtltraining.com/get-a-trade 0800 085 2308 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 21

Reflections of a Windrush Descendant

My

parents and extended family were among the group of immigrants in the 1960s for whom attempts were made to legislatively address the depth of racial discrimination and societal exclusion they faced; for example, being denied public housing, while at the same time being also denied a mortgage or the ability to purchase insurance, all because of the colour of their skin. The Race Relations Acts of 1965, 1968 and 1976 emerged, offered varying degrees of protection against racial discrimination, with each Act strengthening weaknesses in the preceding one.

The Race Relations Act 1965 was the first Act but did not provide any relief to my relatives from any of the fundamental barriers that society had constructed for them (and others). Within months of its enactment, the defects and deficiencies of the Act were obvious; for example, the Act made discrimination in some limited respects a criminal offence punishable by a fine. However, people who discriminated, such as landlords and business owners were prepared to pay damages in civil cases, or a fine in a criminal case, as the price for continuing to subject a section of society to acts of indignity. It therefore could not have remained in place if racial inequality were to have been treated as a serious social problem.

The pressure to address these short¬comings was immediate and extensive, which coincided with the Political and Economic Planning (PEP) report that was published in April 1967. The report documented multiple instances of racial discrimination and concluded that there was substantial discrimination in Britain against non-white immigrants in employment, in housing and in the provision of certain services, such as motor insurance and car hire. The report was largely responsible for the 1968 Act which followed but could also be seen as representative of the process of the changes taking place at the time, particularly in the United States. Consequently, Parliament yielded to pressure and the second Race Relations Act was passed in 1968, strengthening the provisions of the 1965 Act.

The Race Relations Act 1968 prohibited discrimination in both public and private employment, housing and public facilities; this was crucial because these were the spheres in which discrimination against the newly arrived immigrants took place most frequently and had the most significant bearing on most aspects of their

everyday lives. Additionally, discrimination within the terms of the 1968 Act later became known as direct or intentional discrimination.

The Race Relations Act 1968 therefore began to prevent and even dismantle barriers blocking equal access to services, public facilities, housing and employment. However, the legislation being based on complaint system belied its weakness; thus, a new strategy became necessary, which was provided in the Race Relations Act 1976 Its significance was not only tightening up against race discrimination in employment, providing some protection from summary dismissals of black workers from their jobs, as often occurred, but also legislated against direct discrimination. It moved the problems of racial disadvantage away from being deemed to be one solely on the basis of interpersonal relations and laid the foundations for my family to become homeowners and later the more comprehensive Race Relations Act 1976 and consequent policies and regulations that have since advanced equality generally in the UK.

DR VIVIENNE CONNELL-HALL (PHD) Sociologist and Visiting Lecturer in Social History

22 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

A CAREER THAT Join Essex Police www.essex.police.uk/fitthebill values difference Apply Now BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 23

The History of Encyclopedias on African History: Dispelling “Dark Continent” Myths

Last year, Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa signed copies of a special edition of an encyclopedia entitled ‘The Africa FactBook’, to be sent to all the heads of states in Africa. These were limited physical copies of an 800 page tome.

The blurb for the encyclopedia in part read: “The Africa Factbook is a response to 500 years of silence whilst others spoke on our behalf.” It is also sub-titled ‘Busting The Myths!’ President Mnangagwa explained the reason for the sub-title, saying:

“The myth that black people of Africa have no history. The myth that the great Zimbabwe walls were not built by us indigenous local people. The myth that Africans have never invented or discovered anything. All these and other myths are solidly busted by scientific facts, implacable sources and astute scholarship.”

His forthright assertions makes it is necessary for us to go back a bit into history. The late 19th British explorer and colonialist Henry Stanley dubbed Africa the “Dark Continent”. Certainly not a term of endearment. Before then, the German philosopher Georg Hegel opined: “Africa is no historical part of the world; it has no movement or development to exhibit.”

Such 19th century thinking helped embed the negative views of Africa that still persist. As if that was not bad enough, British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper in the mid-20th century, 1963, to be precise had this to say:

“Perhaps in the future there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none; only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness.”

What is shocking is that Trevor-Roper was a highly placed Oxford University history don, who was either ignorant, a white supremacist, or both. Because had he cared to read on the subject before mouthing off, he would have discovered that British journalist and historian Basil Davidson had published two books four years prior – ‘Old Africa Rediscovered’ and ‘Lost Cities Of Africa’, which spoke to

Africa’s advanced civilisations before the arrival of the Europeans.

Of course, this besmirching of Africa's history and reputation, and the whitewashing or hiding of Africa’s history and achievements, isn’t new.

One can not talk about the way African history has been treated, particularly by the European power structure, without mentioning the word – epistemicide. This is one of the definitions that can be found on the Quora online site:

“It's a systematic destruction of any indigenous knowledge base. Any knowledge which doesn’t converge with the perpetrator’s knowledge system. The term can, for instance, be used in the context of the British imperial subjugation of its colonies’ traditional knowledge system during the 19th and 20th Century.”

In South Africa, the discovery in 1932 of the Golden Rhinoceros, a 13th century artefact from the southern African Mapungubwe kingdom, was kept hidden by the apartheid South African regime. Because such an intricate artefact made by Africans some 800 years ago, went against the racist apartheid philosophy, which depended on the promotion of Africans as inferior and incapable.

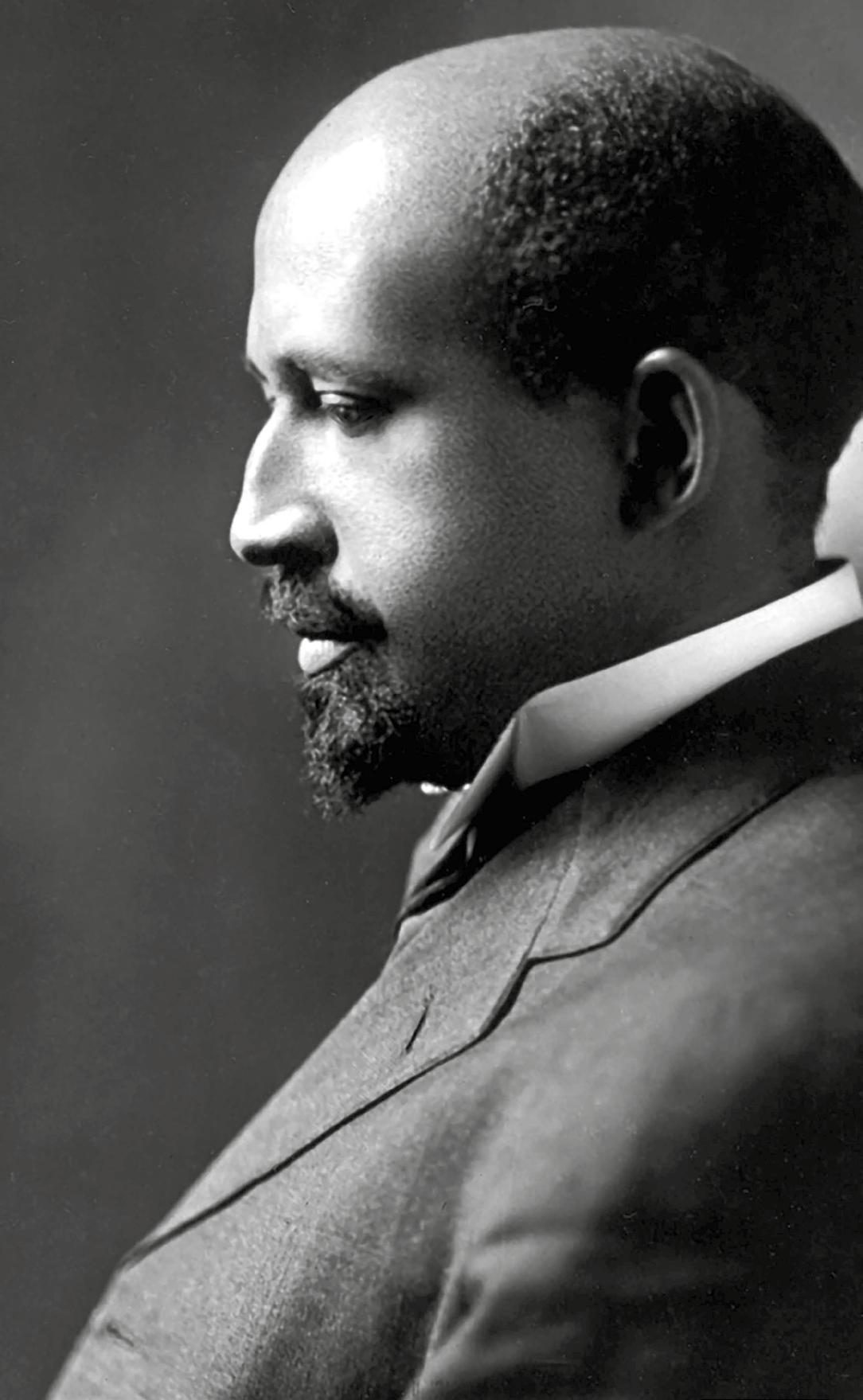

Over in the United States, a revisionist history of Africa was one of the ways used to put down African Americans. To redress the damage done, WEB Du Bois, who is said to have in 1895 become the first African American to earn a Ph.D in history from Harvard University, envisioned in 1909 an

encyclopedia that covered the achievements of Africa and people of African descent.

It took Du Bois over fifty years to begin to realise his dream, when President Kwame Nkrumah facilitated the relocation of Du Bois and his wife to Accra, Ghana in order to work on the ‘Encyclopedia Africana’.

“I want the proposed Encyclopedia to be written mainly from the African point of view by people who know and understand the history and culture of Africans,” wrote Du Bois, as he began work in early 1962 as the Director of the Secretariat for the Encyclopedia Africana Project. Sadly, his work did not get far, as Du Bois died less than two years later, aged 95 years old.

According to my father-in-law, who was an aide to Nkrumah, Du Bois’ death was a double blow. Not only had Nkrumah lost a friend – they had known each for several years within the pan-Africanist movement, but also because Nkrumah was eager to have a book that trumpeted Africa's achievements and boosted the African's confidence. Just like how Nkrumah was using his African Personality philosophy to promote race-pride and confidence.

The Accra-based Secretariat still exists, though it has been perennially hamstrung by lack of funding. Since 1977, it has published three of its target of 20 volumes of the ‘Encyclopaedia Africana: Dictionary Of African Biography’, which provides biographies of personalities confined to a couple of African countries per volume.

However, there are a number of

24 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

BY KWAKU

ambitious publications that cover a wide breadth of Africa’s history, culture, and contributions to world civilisation.

In 1999, the first edition of ‘Africana: The Encyclopedia Of The African And African-American Experience’ was published as a single volume. It was edited by the academics Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, and has now expanded into a multi-volume edition.

But well before then, UNESCO envisioned in 1964 a series of encyclopedias to widely cover Africa’s history across various periods and disciplines. The aim was “to remedy the general ignorance of Africa’s history”. Since 1980, UNESCO has published eight volumes of the ‘General History Of Africa’ series, with three more planned to complete the collection.

In 2014, the Encyclopaedia Africana Project proposal put forward by Ghana for the “documenting African history towards durable solutions to African challenges including forced displacement”, was adopted by the African Union.

Since then, the ‘People’s Of Countries’ series is one of the Project's planned strands, which aims to provide “a comprehensive compilation and integration of articles on the major ethnic groups of countries, their authentic traditional structures and practices of education, economic, religious etc. and other major social institutions as well as the basis for the integration of all the ethnic groups into a functional state”.

Left: Golden Rhinoceros, a 13th century artefact from the southern African Mapungubwe kingdom.

Right: William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, the American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist and author.

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 25

The truth is that, whilst intellectual capital is in abundance across the African continent, publishers face financial challenges, especially in printing academic tomes. Even being within the African Union sphere, has not gotten The Encyclopaedia Africana Project's two ‘Biography’ volumes to the publication stage.

‘The Africa FactBook’ is partly facing the same fate. The encyclopedia is the brainchild of the Institute of African Knowledge (INSTAK) think-tank, and published by its sister organisation Book Of African Records (BAR) in association with the African Union Commission (AUC). BAR signed a Memorandum Of Understanding with the AUC in 2016 to produce the tome.

However, it probably would not have seen the light of day, had it not been for President Mnangagwa's personal interest in the project. He got the Zimbabwean government to fund the printing of a limited amount of physical copies in 2020. Dubbed the ‘Presidential Version’, although it has some 800 pages, it’s a cut-down version. The complete encyclopedia has 1,184 pages.

“At the moment we are short of funds to publish the full version of the book,” laments the encyclopedia’s editor Baffour Ankomah, a former editor of the Londonbased New African magazine. “We only published the shorter version last year. So any groups in the diaspora that can help with funding are welcome. The book has been at the printers in South Africa since early June 2021.”

In the meantime the ‘Presidential Version’ has been made available as a free download on the African Union website. It starts with a chapter entitled ‘Ancient Egypt, our roots!’, which asserts ancient Egypt an African civilisation. And rightly so, as European historians and heritage practitioners have sort to divorce it from Africa. For example, the Egyptian displays in the British Museum are in a separate location from that of the rest of Africa.

And with Elizabeth Taylor’s portrayal of Cleopatra of Egypt embedded in many people’s minds as a Caucasian, it’s no wonder a Harrow councillor at a councilfunded African History Month event I co-organised, said in all seriousness: “Next, you'll be telling me Egypt is in Africa!”

Chapters such as ‘The Moors, Africa’s Gift To Europe’ and ‘How Africa Developed Europe And America’, offer an African counter-balance to the prevalent Eurocentric portrayal of African history. It includes detailed profiles on all fifty-five African countries and much more.

There are pieces, such as the tongue in cheek titled ‘Has A Black Person Ever Invented Anything?’ The answer is of course yes, and several inventors of African heritage are listed. However, apart from a few unknown names to me, such as Dr Raphael E. Armattoe (1913–1953), a Ghanaian runner-up for the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1948, who found the cure for the water-borne guinea-worm disease in the 1940s, I would hope the complete edition provides a more diverse list, including those of the 21st century. That said, this richly illustrated book is an absolutely useful resource for anyone interested in the history of the continent of Africa and its inhabitants.

I marked the last day of August with an event I organised called African History Reflection Day: The Global African People's Forum. It featured a video contribution by Prof Sir Hilary Beckles, the Vice Chancellor The University of the West Indies. In addition to explaining why the concept of pan-Africanism “has to step back”, he said that he no longer supported the concept of an African Diaspora. He’s now advocating for Global Africa, a unifying concept, which makes no distinction between, nor separates, the continent and its Diaspora.

His view has had an impact on the on-going work on the remainder of UNESCO’s ‘General History Of Africa’ series. Because hitherto, the eight volumes thus far published – these are freely available online and in a number of colonalist and African languages – have focused solely on African history located on the African continent. But now, space is being made to include African history of the Diaspora.

The history of the history of African encyclopedias continues. A statement from Prof Beckles’ office points out that: “He is a co-editor of Volume 9, a UNESCO ‘General History Of Africa’ which is called ‘Global Africa’. The volume looks at Africans wherever they are in the world throughout history. The editorial work has been completed and the manuscript is currently with UNESCO. It will hopefully be published soon.”

This shift redresses the defiency which meant that Africans outside of Africa were “no longer part of African history. You are now a part of British history. You're now a part of American history. You're part of Asian history, but you are no longer within the parameters of African history, because you have left the continent.”

So how did the ‘General History Of Africa’ series come about, what have been the challenges and what is the plan, going forward? UNESCO representative in Ghana Abdourahamane Diallo provided the answer at the 2022 African History Reflection Day meeting.

He said that it was the African countries upon joining UNESCO, after attaining ‘independence’ in the 1960s, that “asked UNESCO to help them re-write the story of Africa – that’s what they did.

“The eight volumes were ready in the ‘80s. But to what extent have these volumes been shared? They are not known in the fifty-five African countries, nor in the Global Africa or in the Diaspora. They are not known. They are still to be valorised.

“So UNESCO tried for more than 30 years now. With the member states, there have been lots of resolutions. Even at UNESCO level, but also the Africa Union resolutions with member states committing to include it in their curricula. But still so far we can count on one hand the countries that it's really journeyed in … so the road is still long for the sharing of available information, because it is that information which build the mind, which free the mind, because it's facts, it’s science, it’s not ideology.

“It's history – it’s there. But there’s still a big gap, and we at UNESCO are aware and recently, at the last General Conference of UNESCO, another resolution said that the ‘General History Of Africa’ will be a flagship priority programme for the next eight years to ensure that each member state really commits and puts it in their curricula. So it’s an ongoing battle.”

There has even been the formation of the UNESCO Coalition of Artists for the General History of Africa, which includes British trade poetess and trade unionist Zita Holbourne, in an effort to attract new and also young readers to the history resources, by using arts and culture.

Finally, there’s a much quoted African proverb, which says: “Until the story of the hunt is told by the lion, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” However, it would seem like until Africans and African institutions fund the documenting of their history from a pan-Africanist lens, their stories will always be from the perspective of others.

26 BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022

Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa signs copies of a special edition of an encyclopedia

entitled ‘The

Africa FactBook’

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2022 27 VictimSupport @VictimSupport www.victimsupport.org.uk Charity registration: 298028 ©Getty Images victimsupport_uk Leaders in Diversity Award We are proud to stand with you Whether it happened online or in person, recently or years ago, victims of crime can call our free confidential Supportline 24/7: 08 08 16 89 111 You can also access support from us via: My Support Space – an online resource providing a free, safe, secure and confidential space where you can choose how you want to be supported after crime. Registering for an account with My Support Space is quick and easy. Sign up at www.mysupportspace.org.uk/MoJ Live chat – a free, 24/7 service where you can chat to one of our trained supporters. www.victimsupport.org.uk/live-chat You don’t need to have reported a crime to the police to access our specialist support. P2791 Black History Month advert_188x135mm_2022.indd 1 20/05/2022 15:45

Taking a stand

BY COUNCILLOR SANCHIA ALASIA

Theevents of the last year with the pandemic having a disproportionate impact on BAME communities and the murder of George Floyd by American police officer Derek Chauvin, have proved another turning point across the world for race relations. Many Universities have had listening exercises and deep reflection on how they can use these conversations to take real action. The call for action is not a new one, but there has been a shift in the momentum to make real sustainable change in our universities particularly around closing the ethnicity pay gap and the racial awarding gaps for students. There has also been increased impetus to decolonise and make the curriculums that we teach in our universities more inclusive. Statues have been taken down, most notably that of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol during a Black Lives Matter march, with calls that ‘Rhodes must fall’ at Oxford University. Debates have ensued about how society manages these statues and symbols of colonialism and imperialism going forward.