20 minute read

Technology

Filling the gap

Richard Lawn travels to Cornwall to meet Allen & Heath’s new digital console, Avantis

Managing director Rob Clark

Celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2019, Allen & Heath marked a distinguished half-century in the entertainment technology industry with a notable product launch. As an early pioneer of analogue mixers, the company began its digital journey in the mid-1990s. By focusing on affordable, quality audio without sacrificing performance, the brand found a successful gap in the market and has since gained increasing recognition as a pioneer of digital console technology.

R&D director Andy Bell

Following several changes in ownership over its long history, Allen & Heath is now under the stewardship of Audiotonix alongside Calrec, DiGiCo and Solid State Logic, making it well poised to meet the challenges of the next half-century. Having significantly invested in its Cornish R&D team, Allen & Heath continues to listen to its growing database of users by developing products with a ready-made market. Its third 96kHz digital mixer, Avantis, is a 64-channel/42 configurable bus console with twin full HD touchscreens, extensive I/O options and processing from the company’s flagship dLive mixing system.

Product manager Nic Beretta

Remarkably, the console’s origins only date back to early 2017, when managing director Rob Clark threw down the gauntlet to R&D director Andy Bell to plug the gap between the successful dLive and SQ platforms. ‘At the outset, the internal development name for this project was “Bridge”,’ explains Bell. ‘We knew from our customers exactly what was needed – a console that could handle higher channel and mix counts than SQ but was accessible at a lower price point than dLive.

‘Meeting one of those criteria would be simple, but meeting both would not. So, I started sketching out different concepts, trying to find a winning formula. The first key decision was to integrate the I/O and processing in a single unit, which immediately sets it apart from dLive, which has a more flexible, mix ‘n’ match architecture. Initially, Avantis took a lot of inspiration from SQ but, as we got further into new ideas such as screen integration along the bottom edge and the channel strips migrating onto the glass, it rapidly took on an identity of its own.’

The first simple 3D creative of Avantis was a 1:1 cardboard model with printed graphics glued to its exterior. This visual basis allowed the extensive R&D team to add their input into the initial design. Of the 55 engineers in the department, 20–25 of them worked on the Avantis project. ‘The team got around it and knocked the corners off it,’ recalls Bell. ‘They were asking: “where does this button go?” or “how do I get that feature?” So even before anything had been built, we were trying to balance economics with materials and to stimulate new creative ideas.’

Input was also received from working audio engineers throughout the process. ‘Every detail was discussed and challenged along the way as we advanced through increasingly sophisticated prototypes,’ continues Bell. ‘The decision to substitute a normal rugged plastic with the diecast metal chassis that is a distinctive feature of Avantis was made very early on. So it was a journey, which it always is, but we’ve ended up with a console that is close to what was initially intended, despite a few wrong turns along the way.’

Allen & Heath has made much of the technology platform underlying its current generation of 96kHz digital consoles. First seen in its dLive series and later miniatured for use in SQ, Avantis is the third mixer to benefit from the company’s XCVI FPGA core. ‘Console designs previously incorporated a number of discreet chips, each one processing eight channels of audio with a number of limitations,’ explains product manager, Nic Beretta.

‘Now, it’s all integrated into a single FPGA core, for which the single chip is pretty much the size of a stamp. Yet it’s incredibly powerful, providing dLive and Avantis with an ability to mix all the input channel counts and all the processing with only 0.7ms of system latency from input to output. I don’t think there’s another competitive console on the market that can achieve this with the same amount of processing. In addition, all the mix outputs are phase coherent, regardless of the path that you take internally in the console.’

Encased in its alloy shell and tubular frame, the Avantis control surface is centred on two full HD touchscreens with corresponding rotary controls. ‘Having two touchscreens isn’t a new concept, but we realised we could use it to unlock exciting new possibilities,’ explains Bell. ‘This led us to develop the Continuity UI. Within seconds of getting hands-on with Avantis, engineers appreciate the seamless flow between the physical controls and the on-screen software.

You can work gains and pans on the rotaries, then, at the touch of a soft key, switch to EQ or dynamics across the whole strip. The console also provides a highly configurable FastGrab tab on the right-hand side of each screen, offering another way to quickly and easily access control of aux sends, EQ, compressor and FX on the currently selected channel or spot channel. With Continuity UI, the user decides how they’d like to work – not the mixer.’

For a digital console to make its mark, intuitive features are a prerequisite. ‘Upon their first inspection of Avantis, engineers often ask where the select key has gone,’ Bell continues. ‘However, within two minutes, they realise it’s all within the touchscreen user interfaces, where you can do so much more. It’s extremely intuitive with pre-post switching, safes and freeze layers in Continuity UI, and the large symbols indicate whether it is locked or unlocked. The large proportion of touchscreen real estate created many challenges for us, such as stress testing the glass. We spent a lot of time sourcing the right products from the right component manufacturers to ensure it’s reliable.’

Within the Allen & Heath R&D labyrinth, several testing rooms pose as torture chambers for those parts auditioning for a lead role in future console designs. Here, the components including the touchscreens are subjected to real-world tests for long periods, including dust, sand, heat, humidity, sticky liquids, fizzy drinks, vibrations and drop tests. ‘Over the past few years, we’ve started simulating touring abuse and anything that will end up at some stage within a console chassis. As a result, we are confident that the consoles are reliable and fit for purpose. You don’t expect the customers to drop a console, but you need to develop a good stress test for such an eventuality.’

Given the vertical market sectors that Avantis aims to penetrate, flexibility is paramount. While many users will choose to pair Avantis with the 48-in/16-out GX4816 audio expander, Avantis is also part of Allen & Heath’s Everything I/O ecosystem. This allows an operator wishing to build a compact system or a rental company with existing Allen & Heath stock to connect to a large range of audio expander hardware. Avantis is also compatible with the ME personal mixers and IP hardware remote controllers.

For local I/O, Avantis is equipped with 12 XLR analogue inputs, 12 XLR analogue outputs plus AES (stereo in and dual stereo out). ‘Everything I/O is a concept we’re fully committed to,’ explains Bell. ‘If a customer already has Allen & Heath I/O boxes such as the AR2412 and AR84, we want them to have the option of using these with Avantis. Equally, with portable expanders like the DX168, they can easily add more I/O wherever it’s required, or maybe they need the output-only DX012. Altogether, there are 10 different compatible I/O boxes, including wall-mount I/O for installs, which gives Avantis a great deal of flexibility.’

With the integration of the S-Link port on the rear, users can access the full range of audio expanders and system solutions including the ME1, ME500 and ME-U hub from the ME personal monitoring suite. With the addition of two additional I/O ports, each capable of providing 128 bidirectional channels at 96kHz, Avantis can draw on a full range of current dLive option cards. Further expanding the scope for system integration, FOH/monitor splits and multitrack recording, popular dLive cards include Dante (64x64 and 128x128), Waves, gigaACE and superMADI.

Avantis incorporates processing tools including compressors, EQs and the Cornish innovator’s RackExtra FX units with 12 slots. The optional upgrade to dPack expands Avantis further with additional dLive processing

including the Dyn8 dynamics engine, DEEP compressors and the Dual-Stage Valve preamp. For a one-off payment, dPack purchasers automatically receive all future DEEP and FX updates free of charge. Differentiating Avantis from SQ and dLive, the dPack element of Avantis took a long time for the software engineers to conceptualise, Bell admits. ‘All these tools are included as standard with our flagship dLive systems, while on SQ the user can buy individual add-ons. For Avantis, we’re offering the convenience of a one-time key for access to all the additional processing.’

The fact that the head mechanical engineer at the company was previously an army tank commander goes some way to explaining why Avantis further distinguishes itself from the pack with its all-metal chassis frame. ‘Avantis is encased within a super-strong tubular frame, or exoskeleton, and a die-cast chassis,’ Bell continues. ‘That gives it a lot of rigidity during transport, while adding a very dynamic, distinctive aesthetic look. Not only does it look stunning but I feel the time has arrived to depart from plastic, which is becoming a relevant environmental topic. The market may be used to plastic, but there is a lot of negativity surrounding it. This is our opportunity to replace plastic with something that is stronger and more durable.’

As any R&D director will testify, bridging the gap is one of the trickiest acts to balance. ‘The mission from the outset was to breathe some excitement into the 64-channel mixer space, which is littered with 48kHz old-school consoles,’ says Bell. ‘In many ways, maybe it would’ve been easier to create a scaled-down dLive or scaled-up SQ to fill this space, but the more we examined what customers were looking for in this area, the more certain we became that we needed a new solution. Avantis brings next-generation performance across the board. Technicians in venues, houses of worship, touring and the rental market are going to be seriously impressed by how well this ticks the boxes. It’s a really exciting mixer at a compelling price.’

Tasked with advancing sales of Avantis, Beretta applauds how the in-house engineers managed to complete the two-year tightrope challenge. ‘In terms of the key differences, we see dLive as a much more flexible distributed system. dLive is not only more scalable in terms of inputs, outputs, channel count and bus count, but also in terms of the distribution of different processing and control elements where you can mix with or without a control surface. With dLive, you can mix and match from a range of seven different rack engines and six different surfaces and then start building a system around them with controllers, GPIO interfaces and networking cards. Avantis distinguishes itself more as a standalone mixing console. By incorporating the mix engine and the control elements together with the XCVI core, Avantis fits the classic FOH, monitor or broadcast mixing application perfectly.’

Looking back over the two-year Avantis journey, Bell recalls when those first concept sketches took on life. ‘Continuity UI was central to the design but, as it was all on paper, I was anxious as to whether it was going to work. We were attempting to create a seamless blend between what you see on the screen and the physical controls. I was sitting there looking at it on paper, worrying if our users were going to understand this. When we first powered it up, I could see it all come together on the display. It worked, and served as one of those moments when you realise that you’re on the right track.’

With that flicker of electrical energy sparking up the twin 15.6-inch touchscreens, the bridge had been built, the gap filled.

The next phase of AVoIP

Matrox shows its first AVoIP products at InfoComm 2012

Samuel Recine, sales director at Matrox, discusses interoperability, brand competition and a brave new AV world with open standards

The AV mafket has been streaming video for many years. The entire video telepresence market, for example, was based entirely on finely tuned, high-quality video in optimised low bitrates.

Even though streaming video and audio-over-IP was in heavy use for large facility and multi-site applications, it wasn’t until around 2010 that first-movers in the AV industry began to speak about replacing core onsite AV infrastructure from baseband analogue and digital audio/video extension and switching with an AV backbone that functioned entirely over IP as well.

As with any disruptive changes, many leading incumbents in the market resisted the notion. Selling proprietary switches was far too lucrative. So, for several more years, the market was treated to public discussions about the resolutions, quality, latency and other performance characteristics that could or could not be achieved over IP.

But customers had eyes and ears and could see for themselves that it was clearly possible to achieve the same level of content quality and performance using IP instead of hardwired baseband technology such as VGA in analogue or HDMI and HDBaseT in digital. Before long, every major AV manufacturer had launched some products that could support AV extension and switching over standard IP.

Corporate, government, military, medical and other end users were also simultaneously experiencing advances from the IT world and using everything from Netflix for entertainment; to YouTube and Facebook for training and marketing; to Skype and Zoom for collaboration and corporate communications; and to video management systems like Panopto, Kaltura and Brightcove to build, maintain and deliver both live and ondemand, user-originated content.

The end users were exposed first-hand to the billions upon billions of dollars that had poured into R&D budgets from the IT world to advance things such as audio and video encoding and decoding and codecs for compression. The amazing progress in both real-time and on-demand video delivery over bandwidth-constrained environments revealed to users the inevitable convergence of their data, communications and performance AV applications over a common communications protocol.

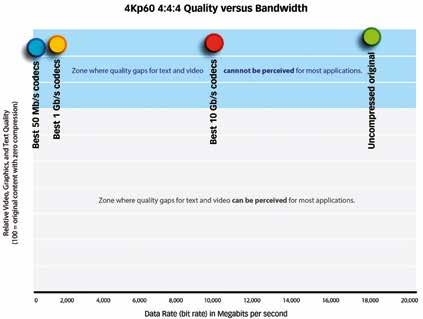

Illustration of quality versus bandwidth

While ‘quality’ has both mathematical and objective measurements as well as subjective elements, one thing the market could clearly benchmark was ‘bandwidth’. The resulting comparison of quality versus bitrate is a matter of fierce debate and can vary by user and by application. But, across a spectrum of users and applications, the graph above shows that for a significant majority of AV applications, the best codecs from all bitrate levels can produce quality levels well above the target zone for text and video quality, and acuity.

Because of the exceedingly low differentiation available over quality versus bit rate, the next argument that surfaced was to slice and dice ‘latency’ again in zones of performance that exceeded customer needs for most applications.

When the source and the destination are in the same field of view, such as a performer onstage standing in front of a jumbo videowall, there is some room for debate about the perceivable threshold such as one frame of latency – ‘glass-to-glass’ – that is, from camera lens transported and displayed on the screen. But, here again, the vast majority of AV applications are not like that. So, what is the acceptable metric for latency?

IP-KVM is a good example. Having the PC several kilometres from the keyboard, monitors, mouse and audio speakers is an application that adequately tests if users can feel the separation when using their favourite applications. This is an application that demonstrates that some users are comfortable at 100ms. Almost 100% of users do not feel the latency at 50ms. So, the amazing, better, best-latency story over IP also died off sometime in early to mid-2018.

And so by ISE 2019 and InfoComm 2019 in Orlando, you could see that just about every manufacturer had product lines or entirely migrated portfolios of products to support highperformance audio/video extension and switching applications over standard IP. In fact, many companies had granularities of uncompressed-over-IP, lightly-compressed-over-IP and highlycompressed-over-IP products in order to give customers choice for their applications.

Uncompressed and lightly compressed AVoIP products tend to use less processing power (so cheaper chips) and therefore tend to have lower selling prices.

When environments require a high density of endpoints and wireless is in play and data, communications or AV are being mixed and leveraged together, when the distances for AV applications are very large, or when the AV needs to traverse portions of network that have potential bandwidth bottlenecks – which is especially common when leveraging cloud or public internet – the products supporting maximum performance at very reduced bit rates are at the fore.

Regardless of the quality, latency or other performance requirements of an application, the market is already serving AVoIP solutions for every application and the market is unquestionably migrating from baseband to IP. So, what comes next?

As the industry’s knowledge of the impact and usefulness of IP-based AV matures, the second wave will clearly centre on open standards, interoperable ecosystems across competing brands and value pushed away from individual widgets and onto technologies and services that create useful interoperable environments that fully leverage the converged world of data, communications and performance media over IP. This breaks down into two topics: open standards and interoperability.

Open standards

This topic refers to the long-term viability of proprietary technologies, whether that means proprietary uncompressed encoding techniques, proprietary codecs or proprietary transport and communications protocols. As markets such as 2D/3D graphics, live two-way communications and so forth have shown, no proprietary technology controlled by a single vendor has long-term sustainability. There are too many stakeholders that have different technological and commercial dependencies for this to ever be viable.

2019 saw the first major discussions in the AV market about potential long-term open standards that can guide the development of technology and products to assure the needs of the maximum number of products, services and user stakeholders are met.

While the discussion has only really begun amidst shipping products, some of which are based entirely on open standards and others based on proprietary technologies, at least some viable alternatives were laid down for the first time last year.

For example, AIMS started a Pro AV Working Group to engage with the community of end users, manufacturers, systems integrators, application developers and service providers to establish if the open high-performance media standards recently adopted by the live broadcast industry could be enhanced and adapted for open standards and interoperability in AV. The group of standards being presented by AIMS is encapsulated by the larger standard known as SMPTE 2110. This consists of multiple sub-standards to regulate encoding, video parameters, audio parameters, asset discovery on networks and security.

2020 will likely see the lively discussion about what existing, enhanced version of existing or entirely new standards will serve the needs of the industry for the next decade.

Matrox's Samuel Recine

SMPTE 2110 already has provisions for low bandwidth environments all the way up to 25Gb/s (widely expected to be the next super node), 40Gb/s, 100Gb/s and beyond. This satisfies the most enhanced use cases for 4K, 8K and onwards. So, again, open standards deal with engaging the long-term requirements of all the stakeholders and is mainly about making investment decisions into things that have a viable future.

Interoperability

Open standards just ensure that the core technology itself is supportable and continues to evolve with the necessary ingredients to meet the requirements of the market over the long term.

Interoperability deals with hardware and software products playing nicely together. Some products in the market work with other brands. Sometimes this even includes competing brands. For example, an IP camera produces a standard H.264 stream. The codec and streaming protocols are based on open standards.

But then, if the camera vendor only wants their own decoders to be able to decode and display the camera, this device cannot participate easily in ecosystems of products using third-party decoder software running on PCs, decoder appliances or IP videowalls. Or, if the camera has been developed so that it can be integrated into an ecosystem to maximise its usefulness, then it can work with the aforementioned software and hardware products.

Interoperability is ultimately a manufacturer’s choice. Sometimes products are locked down to only work within one brand’s product line. Perhaps the manufacturer is taking responsibility for product interoperability within its family and causes restrictions to reduce its scope of quality assurance testing, technical support and warranty support. But these exclusions come at a price.

When customers want to use the best encoder from vendor A or the top videowall from vendor B, and the leading recording and video management system from vendor C, they are precluded from doing so by products that are locked down and blocked from working with each other intentionally.

Multi-vendor/cross-brand/cross-product interoperability is therefore a step above products based on open standards. You cannot build interoperability without open standards. But you can have products that are based on open standards that are not enabled to be interoperable.

Many customers in AV express their goals in plain terms: ‘I want the kind of performance and interoperability I had with VGA in analogue and HDMI in digital. But I want to take advantage of IP to remove the barriers to the number or types of devices of my ecosystems and barriers to distances of the devices on my ecosystems.’

This level of both open standards and interoperability is what the live broadcast industry is shooting for with SMPTE 2110. This is in part possible because the end customers in broadcast are very large and hold considerable sway over manufacturers. In the long-run, it seems inevitable that the AV world will need to adopt a significant amount of interoperability to engage the maximum usefulness of AVoIP to end users. It’s the customers themselves that will demand this.

But it’s not immediately the case in the AV industry. AVoIP is de-facto accepted as the way to go. But interoperability is still in its starting stages in AV.

Manufacturing resistance is one barrier. Skills in the integration, installation and services channels to create interoperable ecosystems over IP is another. Improving cooperation and collaboration between AV stake owners and IT stake owners is another piece that must evolve in tandem.

In the end, imagine what it would be like to have emails that only work from one brand to itself. The market would simply not stand for that synthetic limitation. But maximum usefulness will not be achieved in AVoIP in one bite. This ecosystem needs to be built by customers, channels and manufacturers.

Ironically, it’s the resistance by some key players to help advance interoperability that has large corporate and government end users looking at alternatives for their workflows and applications. I don’t think AV companies quite realise just how much software and hardware companies rooted in the IT world are coming on strong with useful products for a myriad of AV applications.

Instead of merely competing with each other, I expect AV manufacturers are going to continue to let in other products and schools of thought until they put aside their differences and work towards common goals that help advance the industry and give end users the utility they are paying for.