18 minute read

Interview with María Teresa Márquez

Resisting the Darkness of Boxes: A Conversation with María Teresa Márquez

Melina Vizcaíno-Alemán

Introduction: On March 27, 2021, I had the honor of interviewing Associate Professor Emerita María Teresa Márquez (MTM) in her Albuquerque home. The purpose of the interview was to find out more about her friendship and work with Mr. Rudolfo Anaya. They met in 1974 at UNM when she was a librarian in Zimmerman Library and he was a faculty member in the English Department (1974-1993). Mr. Anaya established the annual Rudolfo and Patricia Anaya Lecture on the Literature of the Southwest in 2010, and I began working with him to select speakers and organize the series in 2015. The purpose of my interview was to document the Anaya Lecture’s “pre-history,” so to speak, and to acknowledge MTM’s ground-breaking labor in the library. I also thought it was important to hear her story, from one Chicana scholar to another. The original recording and transcript are being processed as part of the Rudolfo A. Anaya Papers at the Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections in Zimmerman Library and will be placed alongside documents related to Blue Mesa Review (MSS 321, box 22, folders 7-15). I have edited the interview for length and style and in consultation with MTM.

MVA: Tell me about the speaker’s series you and Rudy organized together.

MTM: When I was at the Center for Southwest Research (CSWR) in Zimmerman Library, I decided that I would establish a speaker’s series and I called it CHIPOTLE. I made a list of people that I would like to invite to come to the library. One of the goals was to increase the number of people coming into the library, not only the students but people from the community. So, I developed the speaker’s series, reaching out to the larger community—because the community was ignored by the library—and then also to the students who really didn’t feel very welcome in the CSWR. I had a dual purpose for CHIPOTLE. Under CHIPOTLE, I invited speakers such as John Nichols and faculty members from UNM, and then I publicized the speakers. I invited students from the English Department classes and students from Chicana/o classes in the Spanish Department. I went out and asked for funds to buy pizzas and cokes. Then I would also buy copies of the books by the speakers I had invited. I would ask the speakers to speak twice, once at noon for the students, and then in the evening for the general public.

MVA: In 1993, presumably after CHIPOTLE, you and Rudy established the Premio Aztlán?

MTM: Right, I don’t remember if he approached me, or I approached him. We talked about establishing Premio Aztlán and Crítica Nueva, and I said that I would organize, and so I did.

MVA: What was Premio Aztlán and what was Crítica Nueva?

MTM: Premio Aztlán was the award for best book published in the current year. I would go on

the Internet and look up books by Chicana/ Chicano writers, which was very difficult because established publishers were not publishing many Chicano and Chicana writers, so I had to use alternative means of seeking out the books. I then would read them and give the list to Rudy. He would buy the books and read them, and then he and I would get together and discuss who should get the Premio that particular year. He chose the name Premio Aztlán, I had nothing at all to do with selecting the name. It was Rudy’s decision. He also thought that the critics of Chicano and Chicana literature should be acknowledged for their work, and so he chose the name Crítica Nueva. Again, I would find out who was doing critical work, make a list for Rudy, he and I would get together and we would discuss the writers’ work. Then he would select who he thought deserved the award.

MVA: Tell me more about the Crítica Nueva.

MTM: Rudy thought it was important to bring attention to Premio Aztlán and Crítica Nueva, both would be contributing to the literary canon. We invited Diana Rebolledo, Francisco Lomelí, Juan Bruce-Novoa, and other critics. They worked real well together, and a staff member created some beautiful, beautiful posters to publicize Premio Aztlán. The posters were so well done that they disappeared, they became collectors’ items (laughs). Then a new Dean from the East was hired; she didn’t know much about Chicano/Chicana culture, or New Mexico history, traditions, and culture. She thought that the library could not afford to support Rudy’s projects. The previous library administration had provided space and the help needed to set up the room where the speakers spoke, the Willard Reading Room. The Dean did not realize how important Rudy was to the library. She cut off all funding.

MVA: But Rudy provided the prize money?

MTM: Yes, Rudy provided the prize money, the library did not contribute any prize money. Rudy and I got together and we talked about whether just to do away with Premio Aztlán and Crítica Nueva. I said, “No, you can’t. You can place it at the National Hispanic Cultural Center library or in the English Department.” So, we went back-and-forth, and he decided that he would place it in the English

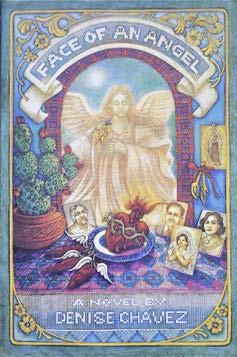

Cover of Denise Chávez’s Face of an Angel, winner of the 1994 Premio Aztlán award. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Courtesy of Daniel Zolinsky

Department. Then we talked about the name. I said, “You have to name it the Rudolfo and Patricia Anaya Southwest Literature Lecture series.” And he agreed, and that’s how the lecture series was placed in the English Department.

MVA: That’s how the Rudolfo and Patricia Anaya Lecture on the Literature of the Southwest came about—a fascinating history. I’ve been organizing the lecture series for the past six years, and I don’t think I realized the connection to these earlier series that you and Rudy put together.

MTM: Well, the lecture series was organized in the library. Rudy and I got together to discuss how the series was to be developed. He provided the money and I did all the organizing. But the Dean did away with the programs, and that’s how the Rudolfo and Patricia Anaya Lecture on the Literature of the Southwest went to the English Department.

MVA: Tell me a little bit about CHICLE. In a recent article, Miguel Juarez calls it “the first Chicanx electronic mailing list created in 1991.” Is there a relationship between the CHICLE list and the work that you were doing for Premio Aztlán and the Crítica Nueva.

MTM: I used CHICLE to publicize the projects. In 1991, I attended the Chicano conference held in Sonora with the goal of building a relationship with Mexico and Mexican scholars. I attended one of the lectures, and some of the faculty, or the speakers, expressed frustration with how slow it was to

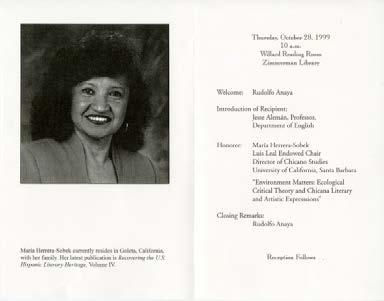

Front and back of program for the third annual Crítica Nueva lecture. Rudolfo A. Anaya Papers, MSS 321, box 23, folder 30.

Permission to publish granted by the Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections.

communicate amongst themselves. After the speakers’ presentations, I suggested to everybody that I could make it easier for them to communicate by using the Internet. I don’t remember if they agreed, or didn’t agree, or they didn’t know what I was talking about (both laugh). I went back to the Zimmerman Library and I developed CHICLE. I spoke with Tey Diana (Rebolledo) and Erlinda (Gonzales-Berry) and told them what I was developing. Erlinda came up with CHICLE, Chicano/Chicana. . .

MVA: Chicano/Chicana Literature Exchange. CHICLE is a clever acronym (laughs).

MTM: (Chewing motion) And it sticks, and it’s sweet, Mexican chicle is sweet!

MVA: Yes! I love the name, I love it.

MTM: Once I developed it, I invited faculty to join and was turned down. I kept trying and trying. I got an assistant to help me. Tey (Marianna) Nunn was one of my assistants, and there was another young woman mentioned in the article (Renee Stephens). They both really worked hard, and there was also another assistant who later became a professor (Janice Gould). I kept trying and trying, I didn’t give up, because I knew it was going to work, I knew it would work, the faculty were just behind the times and they were slow to catch up. One day, my assistant checked and about 800 persons had joined CHICLE. I said, “Oh! I did it! I did it!” (both laugh).

Program for the third annual Crítica Nueva lecture. Rudolfo A. Anaya Papers, MSS 321, box 23, folder 30. Permission to publish granted by the Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections.

MVA: How long would you say it took to get the 800 people?

MTM: A year.

MVA: Now we can’t do without email and listservs. You were way ahead of your time. So, what happened to CHICLE?

MTM: The library administration decided they could not afford to give me a work-study student, and I could not do it by myself. Additionally, what I was doing with CHICLE was not viewed as library work. That I needed to stay—(indicating a small box)—and I was not going to (shaking finger)—no little boxes for me. I didn’t know my place as a Chicana faculty member. I decided it’s time for me to stop CHICLE, because I could not do it by myself, and I was not going to get credit for my Internet work. I did not get any support from my colleagues, so I stopped. People would ask me not to stop, but I couldn’t do it anymore. Various persons tried continuing CHICLE, but when they realized the amount of work required, they gave up the idea. What followed CHICLE was La Bloga, and they’ve done a wonderful, wonderful job of publicizing, interviewing, reviewing—but it’s a whole team, whereas with me, it was just me (laughs).

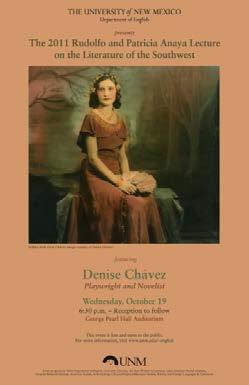

Poster for the second annual Rudolfo and Patricia Anaya Lecture on the Literature of the Southwest featuring a photograph of Denise Chávez’s mother, Delfina Rede Faver Chávez, also on the cover of A Taco Testimony. Reprinted with permission of the author. MVA: CHICLE began as an international effort. Chicano and Chicana literature has an international appeal. Bless Me, Ultima, for instance, has been translated into a number of languages. Can you talk more about Rudy’s global influence?

MTM: Oh, yes. Faculty and scholars would come to Albuquerque specifically to do work on Rudy’s books. I used to have a collection of his books and every book in which he had an article or an essay, but I gave all of my collection of Rudy’s works, including my other 2,000 books to the (National) Hispanic Cultural (Center) library. (Those books have not been processed yet, because the NHCC staff is working on a very limited budget from the State.) Scholars would come and seek me

out because of my working relationship with Rudy. They would come from other parts of the world to do their research, and I would help them because I was familiar with all of Rudy’s literature. I had read all the articles and everything. Then I would direct them, point them to the right direction. I would also print out articles about Rudy’s work, where his work was quoted, call his attention to MA theses and PhD dissertations on his work. I was Rudy’s personal researcher. One of the major professors was Horst Tonn from Germany, who did quite a bit of work on Rudy, as well as Mario Materassi who came to Albuquerque from Florence, Italy, Michele Battalico from Bari, and José Antonio Gurpegui, among other scholars. I would get requests from China, India, Mexico, Russia, and Siberia about Rudy’s work. I was invited to participate in a conference in Chita, Siberia at the university. I also presented my work (not published) on the Chicano and Chicana mystery writers in Moscow, Russia, at the State University of Moscow. That was quite an experience. The professor who organized the conference in Chita came to Albuquerque because she was very much interested in Rudy’s work.

MVA: What about his work attracts the international attention?

MTM: It’s universal. Rudy’s work is universal: family, love, challenges, religion, beliefs, culture, tradition, language. The importance of language, the importance of keeping the language, because it is through language that we remember our history. You find those elements in all cultures, and I think that’s what Rudy has in his work. Rudy’s work is historical, social—

MVA: Mythical, too.

MTM: Mythical, mythical. The storytelling is very important. You find storytelling in all cultures.

MVA: I think that might be the appeal of his children’s literature.

MTM: When Rudy wrote the children’s books, he wrote them with a purpose, to get children to read. His point was: read, read, read, read, and learn! And this woman who I never had the pleasure of meeting (Mary Rose Montalvo, who sadly passed away in May 2020), she was very instrumental in establishing the Rudolfo Anaya Summer Reading Program, and also instrumental in getting the State to recognize Rudy’s work.

MVA: There’s now a State holiday on his birthday (I Love to Read Day on October 30). Since we’re on the topic of Rudy’s work, I want to ask about the adaptations of Bless Me, Ultima, the film and the opera. The film came out in 2012, and the opera premiered in 2018. You say something about the film in an interview you gave to the Rudolfo Anaya Digital Collection, that you feel like the landscape is the main character. Talk more about that, because I love that idea.

MTM: Yes, I thought that in the film the landscape was the main character, overpowering all the characters in the film, because it was so strong, it was beautifully presented. Despite the harshness of that

land, it is full of life! Different kinds of birds, weeds, medicinal herbs, different types of grasses, different types of animal life. You don’t see that in the film, but they’re there, you know that there’s life. Once, I had a visitor from Los Angeles, and we were driving from El Paso back to Albuquerque, and he said, “The desert is so plain, there’s nothing out there.” And I thought, “How wrong he is, he doesn’t see the grass, the weeds, the bushes and grass growing by the road—that’s life! But he didn’t recognize that underneath those little bushes are little animals or insects, ants, or other desert life! But you have to be open to see what is there. I thought that [Carl] Franklin saw—even if he didn’t show the specific animal or plant life— you could imagine and see nature because it was so well-done. The colors of the sky painted a landscape that drew the audience and was full of emotion. In the opera, I thought that no one character stood out. I thought that they were all kind of treated the same. The opera was limited by stage space—the stage at the Disney Theater is not large—but I thought the stage designer did a very good job with what he had, and the costumes also were of the period. There were a few little things that were a little off, but overall, I thought it was well-done—not as much as the film because you have two different approaches, and one with more limitations than the other. But I didn’t think any one character stood out for me, anyway, in the opera. The singers were just wonderful, they did a great job of singing. At one point, one of the songs nearly brought me to tears. I developed a friendship with Héctor Armienta (the opera composer), and I met his mother, his sister, and his marriage partner. We would talk. He was very difficult to get to because he was so busy when he came to Albuquerque. Héctor and Rudy got together ten years ago to bring the opera to the stage. I applaud Héctor for being determined and perseverant in pursuing his goal. He got support from the Hispanic Cultural Center Foundation; one of the conditions for support was that Opera Southwest would include an opera in its season that would appeal to the Hispanic, Hispano, Chicano, Spanish-speaking, bilingual audience.

MVA: I’m interested in knowing what your hope or vision is for the future of Rudy’s work.

MTM: Oh, I have a whole, broad vision! What I see on Rudy’s work is to have a course taught strictly on his children’s literature. I have a vision of holding a symposium and inviting scholars from all over the world to come and present their work. Invite graduate students who have done their dissertations on Rudy’s work, up-and-coming scholars who could consider doing dissertations on Rudy’s work, because not everything has been covered. Most important, the general public should be invited to a speakers’ series to present their experiences in reading Rudy’s work, their connection to Rudy through family. It would be interesting to hear how Rudy’s books have influenced their lives. There’s a lot there. You asked me prior about Rudy’s attitudes towards women. I haven’t kept up with the scholarly work done or being written currently on Rudy’s views on women, but I don’t think that has really been thoroughly explored: women, cooking, and home life. Rudy loved women. He loved his mother and her cooking, and he loved especially his sisters.

MVA: Cooking in literature has a whole history in New Mexico, but it also appears in Chicana literature,

like Denise Chávez’s A Taco Testimony, Demetria Martínez’s Mother Tongue, and Ana Castillo’s So Far from God. Rudy’s whole mystery novel series, with Rita, the restaurant, and the food in that book—

MTM: I’m a character in Rudy’s first mystery novel, Alburquerque.

MVA: Which character are you in that novel?

MTM: I’m the librarian who’s never there (laughs).

MVA: Always behind-the-scenes (laughs)!

MTM: Rudy has a way of including some of his friends in his novels. That would be interesting to find out. I think it would also be difficult to find out. But I am in his first mystery novel.

MVA: I think a lot of that would require these oral histories, or just talking and meeting people and connecting the dots in a way that would allow someone to see how Rudy incorporated his real life into these fictional universes that are universal. The dynamic appeals to people, the stretch to universal themes that people can relate to, but then at the same time being very local and specific to the place and the community—the food and the traditions that have developed over time here. I think that’s why people here love Rudy’s work so much.

MTM: One time I was told by another writer that he thought Rudy was not a good writer. He may not be as literary as some other writers, but he really reaches his people, his audience. Rudy knew how to write for his audience. As for my vision, I would like to see the whole West Wing (of Zimmerman Library) named in Rudy’s honor. I would like to see Rudy’s books for sale, postcards with pictures of his medals and photos of the ceremonies held in his honor, as well as his children’s picture books. The Tourist Department right now promotes the culture, the outdoors, and the arts, but does not promote the writers and the literary arts that the State’s environment inspires. If the West Wing becomes the Rudolfo Anaya West Wing, then you can include books and other items for sale and work with the Tourist Department to include the Rudolfo Anaya West Wing as a point of interest in the State and internationally.

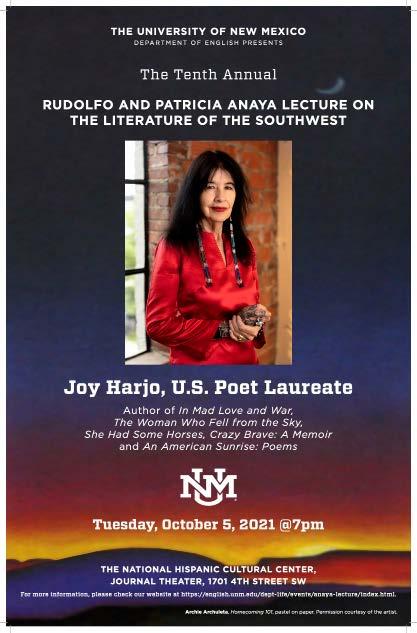

MVA: We’re celebrating our tenth annual Rudolfo and Patricia Anaya Lecture on the Literature of the Southwest (October 5, 2021) and we’re hosting Joy Harjo, who was also Rudy’s student.

MTM: I think she’s a wonderful choice.

MVA: But we’re also at the end. When Rudy made the donation, he said, “This is going to be a ten-year run.” We still have money in the fund and we can still do something else in the name of Rudolfo Anaya, it’s just—what’s the next step?

MTM: This is where the university can work with the Foundation, the UNM Foundation, to give more support to the library and the Rudolfo Anaya West Wing. You need publicity, you need articles in the newspaper, you need articles in the New Mexico Magazine and The Chronicle of Higher Education. You need one person totally devoted to publicizing what the English Department and the library are trying to do. Once approved to raise funds, contact donors and former students, ask for small contributions from Rudy’s readers and large donations from more well-endowed donors.

MVA: You leave me with big shoes to fill, amiga, but I am happy and humbled to try and fill them. Muchismas gracias! Thank you so much for your time.

MVA Note: UNM has officially approved the naming of The Rudolfo Anaya Sala in Zimmerman Library near the Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections where Mr. Anaya’s Medal of the Arts is on display and where his manuscript collection rests. Carol Kennedy is the Director of Development for the UNM Foundation and has been instrumental in this effort. Please visit https://www.unmfund.org/fund/ rudolfo-anaya-sala-fund/ for more information and to donate to this important effort. Contact Carol at carol.kennedy@unmfund.org with any questions.

Works Cited

Anaya, Rudolfo, Alburquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

Armienta, Héctor (composer), Bless Me, Ultima, Opera Southwest, National Hispanic Cultural Center, 2018.

Castillo, Ana, So Far from God: A Novel, W.W. Norton, 1993.

Chávez, Denise, A Taco Testimony: Meditations on Family, Food, and Culture, Tucson: Rio Nuevo

Publishers, 2006.

Franklin, Carl (director and screenwriter), Bless Me, Ultima, Gran Via Productions, Monarch

Pictures, Monkey Hill Films, Tenaja Productions, 2012.

Juárez, Miguel, “María Teresa Márquez and CHICLE: The First Chicanx Electronic Mailing

List,” Medium, 26 December 2017, https://medium.com/@migueljuarez/mar%C3%ADa-teresam%C3%A1rquez-and-chicle-the-first-chicanx-electronic-mailing-list-521be58df9db.

Martínez, Demetria, Mother Tongue, One World, 1996.

Rudolfo A. Anaya Papers (MSS 321), Box 22, Folders 7-15, Center for Southwest Research and Special

Collections, University of New Mexico Libraries.

Rudolfo Anaya Digital Archive, “Oral History Project: Maria Teresa Marquez,” interview by Sophie

Elle, Digital Initiatives and Scholarly Communication, University of New Mexico Libraries, April 11, 2018, https://anaya.unm.edu/node/192.