PREMIER STORY

BREITLING PREMIER, DUOGRAPH AND DATORA

With contributions by Georges Kern, Gregory Breitling and Tim Lake

Vintage watch photography by Elias Hartmann

OPPOSITE:

Breitling ref. 765H, ca. 1940, Hahn cal. 42, 37.2 mm case: steel, hands: Sword

NEXT PAGE:

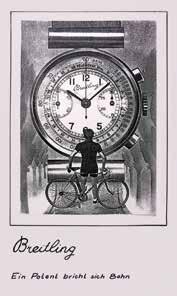

Evolution from the very first Leon Breitling sports stopwatch to the final design language of Willy Breitling’s wrist chronograph

The Premier Story is very much the history of the chronograph, as any book about Breitling must be. It is Breitling’s specialty in every way and each of the brand’s three generations of founders played their part in shaping it. Leon Breitling patented the mechanism that would make his pocket chronographs manufacturable for the masses; his son, Gaston introduced the first wrist-worn version with an independent pusher at two o’clock; and his grandson, Willy, patented the second independent pusher at four. All three innovations were game changers of their times and, together, they defined the wrist chronograph as we know it today.

Vintage Premier, Duograph and Datora are cornerstones of my collection precisely because they represent the modern chronograph’s coming of age. But the best way to understand how it got there is to take a journey back to the beginning, not just to 1943 when Willy Breitling introduced the Premier line, but to 1884, when his grandfather, Leon, made it possible by setting down roots in the rarefied world of Swiss watchmaking.

This is the story of the people and the innovations that converged to define the Breitling brand and usher in a golden age of watchmaking. With the exception of a few fascinating side adventures along the way, that journey has always been about the chronograph.

Leon grew up in the cradle of watchmaking, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. His grandfather Jacob-Martin, a baker-taverner, had settled his family in the town a generation before. Leon’s uncle Charles-Auguste became a watchmaker in his own right who established his company, Breitling-Laederich in 1850.

La Chaux-de-Fonds is recognized today as a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its design as a “city-factory” focused on the fabrication and assembly of watches. Watchmaking started out there as a cottage industry, with most of the trades—case makers, dial makers— taking place in home workshops throughout the town. Residential and semiindustrial workshops shared space in buildings that were organized in parallel strips positioned to ensure enough natural light came through the large atelier windows to illuminate the work benches for the maximum number of daylight hours. Growing up in these surroundings had a profound influence on Leon. From a very

young age, he knew watchmaking would be his calling.

By the time Leon finished his formal studies, those cottage businesses had developed into a full-fledged industrial sector. Leon left La Chaux-de-Fonds to take an apprenticeship with a chronograph specialist in the nearby town of Renan.

In 1884, he was ready to set up his own shop, which he established in nearby SaintImier, another of the watchmaking towns that dotted the lush valleys of the Swiss Jura Mountains. Leon was independent, but regularly collaborated with other relevant companies in the area—Droz, Perret, Favre and Fallet are all mentioned in the Breitling family archives.

His interest from the get-go was the chronograph; it fascinated him. If he grew up in the epicenter of watchmaking at a time when the most relevant complication was the chronograph, it’s quite logical that he caught the bug. There was a lot of innovation going on, and Leon was keen to be a part of it.

After all, he lived in exciting times. The late 19th century was the peak of the Industrial Revolution and owning a chronograph was becoming more essential in all walks of life. Sporting activities ventured beyond the horse racetracks of the rich. Leon witnessed the first cycling races, the first motor races. He saw trains moving at unprecedented speeds, and industry was setting the pace.

It was the era of Taylorism, a scientific management theory where every step of industrial manufacturing and assembly was timed in order to optimize output. An entirely new, modern way of life was emerging, just waiting to be lived—and

timed. Leon saw this new world of speed as an opportunity to share his passion for the chronograph with a wider audience. He was quick to register his innovations with the newly formed Swiss Institut Fédéral de la Propriété Intellectuelle, beginning with the 1889 patent #927, for a simplified chronograph timer with a single wheel and normal toothing. It was one of many to follow that would improve and streamline the chronograph, making it easier and less time consuming to manufacture—a step towards the goal of making it more affordable to the masses. A year later, Leon was officially listed in the 1890 Indicateur Davoine ,

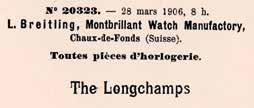

THIS PAGE, LEFT TO RIGHT: Leon Breitling’s first documented advertisement (1891) and his first listing in the Indicateur Davoine (1890), a registry naming all Swiss watchmakers and traders

a registry naming all Swiss watchmakers and traders. His listing reads: “Breitling, Léon, specialité de chronographe, breveté”—a specialist in chronographs, with his own patents. The occasion inspired him to create a logo for the company with a motif that would immediately identify that “specialité.” It was a depiction of a column wheel, the central component of the chronograph, together with his initials, L and B.

In 1892, with his new logo and credentials in hand, Leon returned to his hometown of La Chaux-de Fonds, ready to compete in the watchmaking big leagues. He rented a rather large factory on Rue du Petit Château, in a building shared with another big chronograph company of the period, Couleri-Meri.

He announced his “homecoming” with a full-page advertisement in the Indicateur

LEFT: The 1892 registration for Leon Breitling’s “column-wheel” logo with initials LB

RIGHT: Early Breitling horse-racing stopwatch (1892)

ABOVE:

Registrations for Breitling’s cycle and horse logos (1896) and the name of his horse-racing stopwatch, “The Longchamps” (1906)

RIGHT:

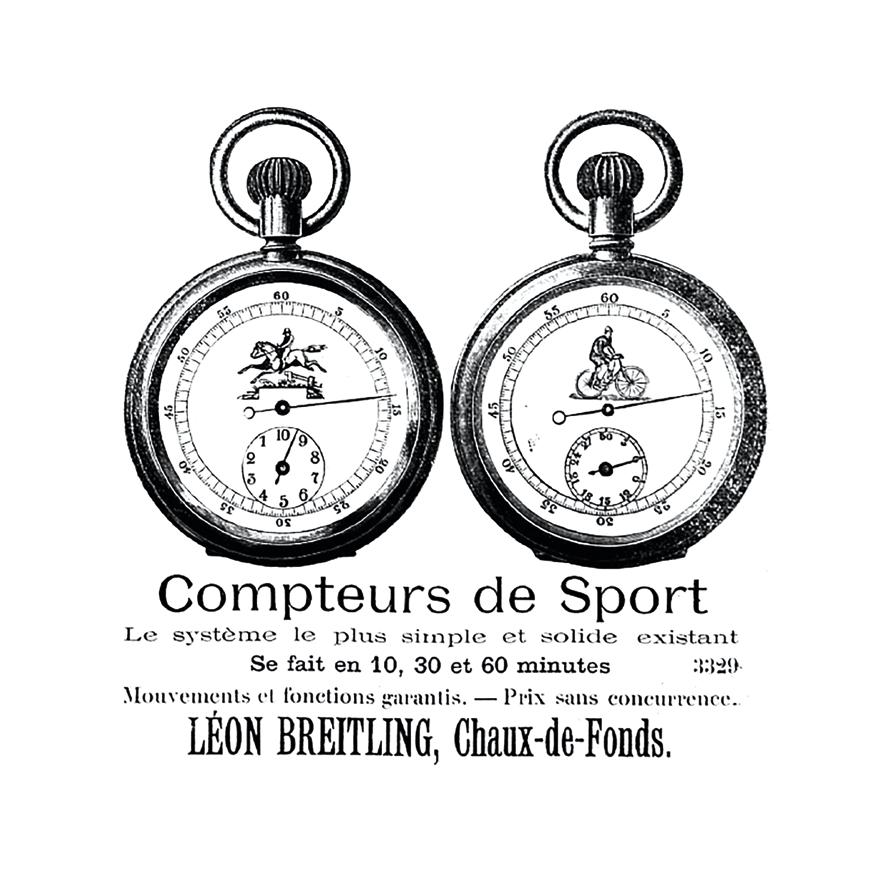

A 1903 advertisement for Breitling’s horseracing stopwatch

Davoine, placed on page two and printed on colored paper, undoubtedly a major expense for the young watchmaker. In the ad, Leon boasted of his patented simplified chronograph movement, showed a chronographe rattrapante and his horse-racing stopwatch (a design he registered in 1896 and named “The Longchamps” in 1906).

Two years later, to Leon’s delight, a large public park was created adjacent to the Breitling factory, and the street was renamed Rue de Montbrillant. Leon

loved the name, and soon changed his advertisements to proudly note that his factory was located at 3 Montbrillant. In 1899, he even changed the company name to “L. Breitling, Montbrillant Watch Manufactory” and registered the logo.

Leon raced into the 20th century in a burst of productivity. Sometime around 1910, he placed an advertisement in the journal of the Fédération Horlogère Suisse, proudly stating that Breitling had sold “more than 100,000 chronographs and stopwatches” since its founding in 1884.

He also registered names for his various specialties. Among them, the 1907 “Vitesse,” a piece that nicely summarized what his work and research had all been about: measuring speed. The Vitesse was a complex and innovative chronograph with a tachymeter scale that could measure and display speeds from 15 to 250 miles or kilometers per hour. We have this innovation to thank for the first speeding tickets.

Speed remained the driving force behind Leon Breitling’s pursuit of the perfect chronograph, and it was a word that applied equally to his aptitude for marketing. He registered logos for watches relating to

horse racing, cycling, motor racing and any relevant sport and activity he could think of, something not widely done in that era. He advertised “compteurs de sport,” stopwatches, chronographs and, from the early 1890s, rattrapantes or split-second chronographs. Breitling also produced specialized tachymeters, phonotelemeters (for timing sound), medical pulsometers (for measuring heart rates), industrial timers and “all automotive specialities,” as stated in a 1910 advertisement. These early endeavors, based on the measurement of speed, went a long way towards establishing Breitling’s tool-watch DNA.

THIS PAGE: 1910 advertisement referring to Breitling’s tachymeters, phonotelemeters and “all automotive specialities”

OPPOSITE:

1895 ad for the company’s various sports timekeepers

Alas, there also came a time to slow down, and Leon Breitling died in 1914 at the young age of 54. His life was short, but his legacy was considerable. Leon had succeeded in building a strong foundation for the Breitling brand. Much of what would be launched in the next few years was already technically complete and ready for production by the time he died.

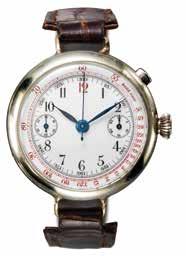

While it normally took years and many prototypes to develop and test a chronograph movement, it took Leon’s son, Gaston, less than a year after he took over the company to introduce a Breitling chronograph that changed everything, and would define how wrist chronographs would function over the next several decades.

This new wrist chronograph, presented in the February 1915 edition of the Fédération Horlogère Suisse, had an independent pushpiece at two o’clock that could be used to start, stop and reset the chronograph. This was revolutionary, since wrist chronographs at the time were really just pocket watches attached to wristlets or with soldered wire lugs, and still activated by pressing the crown at 12 o’clock. Neither their functionality nor their size were ideal, and operating the crown with one hand was cumbersome.

Gaston widely advertised his innovation, which he described as “most practical and advantageous,” and he moved it quickly into mass production.

Gaston Breitling, 1884-1927

Gaston Breitling, 1884-1927

Until this time, wristwatches had been almost exclusively worn by women. Men had waistcoats with pockets where they could store their handheld watch. But Gaston had taken over the company just before World War I. His wrist-worn chronograph with the independent pushpiece proved a well-timed success as, on the battlefield, men no longer had the luxury of being able to dip in and out of their pockets.

The innovation helped carry Breitling through the difficult years ahead, but it did not make the company completely immune to external factors. A passage in Breitling’s 1946 catalog entitled “A Bit of Our History” describes the situation: “Leon

Breitling died on August 11th, 1914. He left behind him a prosperous factory, which his son Gaston took over. The World War, which had just broken out, setting Europe on fire, closed down many of the markets which had hitherto been available, and this caused difficulties for Gaston Breitling.” This is probably putting it rather mildly, since World War I had pushed all of Europe into massive economic turmoil. Even after the war, the global economy continued to decline.

Gaston’s ambition to expand the company turned into a battle for survival as he struggled through those troubled years. It was not an easy task, as the entire Swiss watch industry was in a tailspin and

OPPOSITE:

1915 advertisement for Breitling’s monopusher chronograph

LEFT:

Ca. 1920, Breitling, 38 mm case: 18k gold, hands: Leaf (feuille)

ABOVE RIGHT:

Monopusher “1915” with sterile dial, ca. 1915, Breitling, 42.8 mm case: silver, hands: Spade (poire)

it would take well into the 1920s for the economy to reawaken.

Still, Gaston persevered. The company’s 1946 catalog recounts, “Having traveled a lot and worked abroad and thanks to his wide knowledge of the trade and the world markets, he was able to surmount the crisis and develop his father’s business.”

Along with dwindling output, there remained some ambivalence about the utility of the wristwatch: was it meant to be ornamental, or was it a tool? Wristwatch design was in flux, and as Gaston chased the

market, he explored new uses for his firm’s specialty. In one trademark register, there is a rather surprising product that shows his ingenuity in trying to appeal to different sectors. In February 1923, Gaston registered a product called “Unedeu” (a derivation of “one, two” in French).

It took me some time to find out what it actually was: a three-digit counter on a pocket watch designed for priests so they could count the number of parishioners attending mass without being too obvious about it. It was really a rather extraordi-

nary idea, but it apparently wasn’t hugely successful, because a surviving example of the Breitling Unedeu priest’s chronograph has never emerged.

Another 1946 catalog entry describes Gaston’s ongoing determination to keep the wrist chronograph alive: “According to the family tradition of imagination and invention, Gaston Breitling kept up this specialization of the manufacturing of complicated watches. If Leon Breitling had opened the way, Gaston enlarged and prolonged it.” His dedication would lead

to another foundational innovation, one he filed a patent for in 1923: the Brevet 105532, a chronograph that offered an independent start and pause pusher and an additional independent reset activator in one of the crown positions. It was the first patented chronograph that offered start, stop, pause, restart, stop with a separate reset-to-zero actuator, and it was a defining development for Breitling.

OPPOSITE, LEFT TO RIGHT: Monopusher “1915” with sterile dial, ca. 1919, Breitling, 39 mm case: silver, hands: leaf (feuille)

A page from the 1946 Breitling catalog, entitled “Our History”

THIS PAGE, LEFT TO RIGHT 1923 registration for the Unedeu priest’s chronograph

1923 patent 105532 for the basic concept behind the dual pusher

In 1927, Gaston Breitling died suddenly at the young age of 43 , after running the company for 13 years. His passing left a gap in leadership, as his only son, Willy, was then just 14 years old. An entry in the 1946 catalog says Willy was “finishing his technical and commercial studies” in preparation for taking over the family firm. But that’s perhaps overselling it. In reality, he was still a boy, and for the next five years, the company was managed by his mother, Berthe, along with a succession of administrators that, as Willy later told his son, Gregory, didn’t always work in the company’s best interest.

Willy was not yet 19 when, in 1932, he finally convinced his mother it was time for him to join the family business. Within a year, he proved to her just how ready, willing and able he was to take over the management of Breitling but, because of

Swiss law, he had to wait until he turned 20 in 1933 to be officially entered as company administrator in the corporate registry.

I am extremely cautious in using a term like “visionary” as it is so often misused to describe what may have been luck applied to rather mediocre talent. In this case, however, I think it’s an accurate description of Willy Breitling, who steered the company into the modern era with consistency and aplomb.

Willy’s first step as Breitling’s new leader was to take a deep dive into the company archives, immediately grasping the significance of what his father and grandfather had achieved up until then.

It was in those archives that he found his personal vision about how the watch market, and especially the chronograph segment, would evolve over the decades to come.

OPPOSITE: Sprint, ca. 1928, Hahn/Depraz cal. 3, 38 mm case: plaque, hands: Pencil

OPPOSITE:

Breitling ref. 101, ca. 1932, Hahn cal. 3, 36.6 mm case: plaque, hands: Modern

Willy approached his endeavors like a game of chess, working out each of his moves logically, but with an adventurer’s spirit. The result was a period of unbridled creativity. Year after year between 1933 and 1979, Willy introduced one innovation after another, one iconic model after another, including the Premier. In the process, he not only clarified Breitling’s specialty and brand positioning but shaped the development of the chronograph in general.

One of his first orders of business was to revisit the 1923 patent his father had filed—the independent activation “start, pause, restart, stop, reset” action—and saw that this is what needed to be on every wrist chronograph. Independent pushers at two and four, controlling all chronograph functions, in a movement small enough to perfectly fit every wrist. This Breitling patent still defines the function of chronographs today.

And here we see an example of how myth sometimes gets turned into mythos and eventually becomes accepted as truth. Over the years, I have read in books,

countless articles, blogs and forum posts that Marcel Roberts was a well-known mathematician hired by Willy Breitling in the 1950s to develop the slide rule for the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) Navitimer.

In fact, Marcel Roberts was no “wellknown mathematician” that Willy happened to find in the ’50s. He had been working with Willy since 1932, helping to design Breitling’s dual-pusher wrist chronograph.

Willy’s son, Gregory, told me recently that, as a child, he’d spent a few days at the Roberts family home in La Chaux-deFonds, where Marcel recounted how he had worked through many nights at the watchmakers table in his basement, building wooden prototypes in the process of developing and optimizing the dual-pusher wrist chronograph mechanism. The full story is that Roberts was named technical director of Breitling in the 1940s and did, in fact, go on to help design the slide rule for the original Chronomat—but not for another seven years after the dual-pusher chronograph was patented in 1933.

Now back to Willy who, having established the technological foundation for the product he wanted, was focused on his strategy to bring his chronographs to the masses. He foresaw a quickly developing world where speed, sports and the needs of the military, aviation and industry would make the wrist chronograph a tool that everyone needed to have.

The excellent archives kept by Serge Maillard, publisher of the longstanding Swiss magazine Europa Star, reveal an interview Willy gave to an Austrian watch magazine in 1935 about his vision for a

“popular” chronograph. He references the example of Kodak and its Brownie camera, which had revolutionized photography by turning it from a professional pursuit to a hobby for everyday people. Kodak did it by producing simplified cameras with reduced functionality, thereby eliminating the barrier of unaffordable pricing. “We have to do something similar with chronographs,” Willy had said. “We have to produce an entry-level product affordable to everyone, that will make people aware that this was something they never thought they needed, but now know they do.”

OPPOSITE, LEFT TO RIGHT: 1933 patent 175564 for the dual-pusher wrist chronograph; Willy’s 1935 interview stating his vision for a mass-market watch that would do for the chronograph what the Kodak “Brownie” had done for cameras

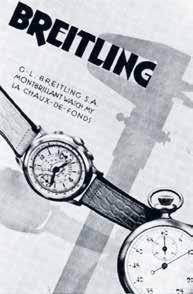

THIS PAGE: 1934-35 advertisements for the dual-pusher chronograph

THIS PAGE:

Montbrillant ref. 709, ca. 1934, Hahn/Depraz cal. 3, 39 mm case: steel, hands: Modern

OPPOSITE:

Sprint ref. 709, ca.

1934, Hahn cal. 39, 38.8 mm case: steel, hands: Modern

Willy believed that every young person needed a chronograph, whether for swimming, running, cycling or driving, and Breitling would be the company that made them accessible. One of the first models he manufactured was a very simple 27 mm wrist chronograph, only able to time up to 60 seconds and only available in chromed cases. The original release wasn’t hugely popular, but it laid the groundwork for more successful models to follow and

set the tone for transforming the chronograph into a mass-market product. His next chess move was to introduce branding to the dial as Kodak had done with the Brownie camera. Most watches sold up until the 1930s had sterile dials, meaning no model name, no logo. These were niche products made for jewelers, sold by jewelers to their clients, and sometimes branded with only the jeweler’s name. Willy began to slowly change

this, but the first steps were hesitant. As early as the 1920s, the “Breitling” mark appears, but only on a few rare enamel dial pieces. Then the “Montbrillant” and “Sprint” names pop up among the sterile mass. By the mid-1930s, Willy was unabashedly branding dials with the scripted Breitling logo but still playing it safe by adding the Montbrillant and Sprint names to his advertising copy to maximize name recognition.

Willy continued to create tool-watch chronographs, but the market for them had yet to take hold beyond professional use. One of his efforts to tap into the pop-

ular zeitgeist resulted in a puzzling foray into decorative cases, a brief trend from the 1920s that he tried to rekindle in chronographs in the late 1930s. These exuberant pieces, called “Dernier Cri,” had elaborately shaped lug attachments that completely overshadowed the functionality of the chronograph. It’s hard to tell whether Willy was truly serious about these overly decorative pieces. Pictures from the 1937 catalog reveal them to be what can only be described as outlandish. To make matters more confusing, he went so far as to register their designs to protect them from copycats.

OPPOSITE, LEFT AND BELOW: A rare ref. 747 from ca. 1942 carries the “LB” logo that Willy’s grandfather had registered in 1892, showing that he continued to experiment with the company’s branding even after settling on the Breitling mark

OPPOSITE, RIGHT: Clamshell ref. 746, ca. 1937, Venus cal. 150, 34.3 mm case: steel, hands: lumed Alpha

There are debates as to what is the “Golden Age of Watchmaking.” Some cite the Roaring Twenties as the great horological decade, when the wristwatch was just coming of age. It was a time when shaped movements—round, square, rectangular, lozenge, barrel, cushion, curved—made any case configuration possible and, with no formal design language yet established, watchmakers had carte blanche to create.

Others consider the Baby Boomer years of the 1950s to be the era when all the magic happened, thanks to that decade’s abundance of elegant, automatic dress watches and the beginning of the dive-watch craze triggered by Jacques Cousteau’s mesmerizing underwater film, The Silent World. You could also make a case for the Swinging Sixties, when so many of today’s cherished steel sports chronographs were launched, or the 1970s when Gerald Genta, the god of watch design, created many of his masterpieces.

All are valid arguments, but for the chronograph collector, the Golden Age of Watchmaking must be the 1940s, when

chronographs found form, function and practical usability, when tool watches evolved into elegant works of art, when all the relevant complications were added to the calibers that we still treat with such high respect today.

This book takes an up-close look at what were considered Breitling’s luxury lines—the Premier, the Duograph rattrapante and the Datora full-calendar—produced from that seminal decade onward.

Breitling’s definition of “Premier” was and still is to be top of the line in every detail: the best calibers, the best materials and the best designs.

OPPOSITE:The 1940s was when Willy Breitling dared to reimagine the chronograph as a practical, personal item that could transcend the niche segments of military and industry. But even that may be an understatement, as I truly believe Willy was hellbent on seeing the chronograph take over the world. Nowhere is that as clearly reflected as when you watch him weave his strategic nets. When move after move seems logical, planned. When a product line is formed in technology, design, positioning, branding and advertising. When you see how he builds his international distribution network with country representatives and wholesale customers like Tourneau, Aerotel, Tavannes, Clebar, Kronometer Stockholm, Singer and Cyma, to name a few, who would market his chronographs under their own brand names.

From the 1950s onward, Willy’s moves are well recorded. Breitling’s archives contain market research, strategy papers, worldwide advertising plans and stylebooks for in-store displays, along with hundreds of pages of studies and sample advertisements. Some of these

were created during Willy’s time as head of the Association of Swiss Chronograph Manufacturers, during which he developed a highly successful strategy for rejuvenating the chronograph—one that would lead to the development of the “Top Time” in the 1960s. The entry-level chronograph aimed at “young and active professionals” did, in fact, bring it back into fashion following a sharp and sustained drop in demand in the 1950s. But in the 1940s, Willy’s playbook was not so precisely documented. We have only the catalogs and watches from that period to tell the story of the elaborate game of chess he set into motion. Willy chose Venus SA to be his main ebauches supplier, his partner in innovation. The last Landeron-Hahn-based models shown in the 1940 catalog would disappear entirely by 1944, just as the “fancy-lug” additions to the original pocket-watch look of the early decades were also gone by that year. Gone too were the last of the “non-exclusive” waterproof steel cases, the Schmitz Freres clamshells, replaced by exclusive Breitling-designed models.

Willy also shows some exaggerated optimism in that 1940 catalog, as he displays the first wristwatch rattrapantes, although it would take until 1943 to be able to mass produce these complex mechanisms. But that was the point: Willy was unrelenting in his ambition. And he was not going to let a minor detail—like not being market-ready—curtail his grand designs.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Willy Breitling, 1944

1945 Duograph advertisement

Aerotel Premier ref. 787, 1947, Venus cal. 152, 34.7 mm case: steel, hands: slim lumed Syringe

The tone of Breitling’s marketing changed in 1944, pivoting from the strictly utilitarian catalogs and advertisements of the early war years to a tone of deliberate optimism. By then, the Nazis were in retreat, the U.S. had joined the fight, and there was a sense that the war would soon be in the rear-view mirror. Breitling channeled that hope by releasing beautifully crafted wrist chronographs in solid gold, including the first ladies’ chronographs. That same year Breitling launched its first full-calendar chronograph, presenting its new “Datora” line as one of the “Novelties of the Year.”

The company was also one of the first to leverage star power. Ads of the day featured Cesar Romero, Hollywood’s “Latin Lover,” and glamorous starlets, with tag lines ringing in the “Years of Elegance.” Another ad depicted a cheerful couple gazing into, what was presumably, a bright future. There was no mention of war, only the inference that life was about to improve dramatically. Willy didn’t wait for the end of the war to plan for the boom ahead. He was ready, with a full suite of products.

A 1945 advertising campaign teased what would be Willy’s post-war masterstroke: a catalogue featuring a whopping 300 new models. The ad encouraged people to pre-order so they wouldn’t miss out, while referring to the upcoming catalog as the “grand finale” in Breitling’s evolution. When the eagerly awaited catalog landed in mailboxes in 1946, it did indeed contain everything: pocket watches, wrist chronographs, aircraft cockpit clocks, pilot’s watches, men’s and ladies’ wristwatches and dedicated stopwatches for every activity you could dream of. People responded, and production rose dramatically. By then, Willy had refined Breitling’s wristwatches into carefully segmented, numbered and branded model lines. The Populaires, containing the up-down Venus 170 caliber, could be identified by three-digit model references, beginning with a leading one (1xx). Meanwhile, the “luxury segment” model lines of the Premier, Duograph and Datora all had column-wheel calibers, and were referenced with a leading seven (7xx). Though, by

then, Willy was offering so many sizes and style variations of these models, he eventually ran out of sevens and had to start assigning eights.

Appropriately, that number ticked over with the announcement of the ref. 800, the crown jewel in the 1946 catalog. The watch brought together a split-second rattrapante, triple-register chronograph, moon-

phase and date. Willy placed the ref. 800 in the Datora section. This was another sign of his overly optimistic ambition, as it would take until 1951 for the complex caliber to finally appear in production ledgers and on assembly lines.

One of the interesting conclusions we can draw from Breitling’s enormous 1946 catalog, is that finding the ideal size for a

PREVIOUS PAGE: A selection of Premiers, Duographs and Datoras from the 1940s

THIS PAGE: From the 1946 catalog, a fullcolor Datora and a reference to the ref. 800 split-second chronograph with calendar

THIS PAGE: A lineup showing the range of watch sizes offered by Breitling in the 1940s. The 33 mms were the norm, while the 38 mms were considered massive

OPPOSITE: Premier ref. 788, 1946, Venus cal. 152, 36.4 mm case: 18k gold, hands: Pencil

man’s wristwatch was as complicated then as it is now. There has never been a right size for every taste and wrist, and that 1946 catalog provides a glimpse of just how many options Breitling offered: small non-waterproof chronographs in 33 mm and 34 mm were the general standard of the period, but Breitling had found that its aviation tool watches were at their most

WATERPROOF MODELS

readable and functional in 37 mm and 38 mm sizes. Then, just to be sure it was catering to mass-market demand, Breitling added a medium-sized range of 35 mm and 36 mm watches. And, of course, customers had to choose between the heftier waterproof models and the sleeker non-waterproof ultra-flat pieces. No wonder that catalog was huge.

NON-WATERPROOF MODELS

Beginning in 1940, Breitling included a page in its catalog outlining the varieties of chronograph scales available (that year there were nine), along with the notice: “It is understood that all these variations can be supplied in all modern executions of dials … when passing orders, kindly state reference numbers concerning chronographic divisions.”

Catalog pages reveal the incredible range of options Breitling offered, which amounted to an almost custom operation. There were simple dials without additional measuring scales, inner spiral combinations of tachymeter and telemeter, external combinations of the two and, of course, the choice of one or the other. You could have a pulsation scale only, or a combination of tachymeter and pulsation. There was an industrial dial available with a decimal scale dividing the minute into 1/100th seconds and a dial labeled for “Production” designed for Taylorist industrial optimization.

Topping off the vast assortment was an almost endless selection of index designs, including Arabic or Roman numerals;

round, single or double batons, printed and colored indexes, applied markers in various metals and shapes. Combinations were also possible. Dials came in a wide array of colors: white, chamois, champagne, gold, copper, salmon, brown, black—some with Breitling’s signature chimera finish, in which colors and patterns appeared and disappeared according to the angle and light.

It’s mindboggling to think how, faced with such a choice, anyone could make up their mind. I have collected Breitling chronographs for decades, and still find new dials I’ve never seen before. I fear I’ll never see or be able to catalog them all—and we haven’t even gotten into hand variations! I hope the next chapters give you an idea of how rewarding the patient and persistent hunt for the next unknown can be.

The sheer variety of design options outlined in the catalogs are a testament to Willy Breitling’s successful strategy to make the chronograph indispensable to daily life. “To Breitling/Geneva, the quality of a watch presents no problem,” he said in one advertisement. “The credentials of the Breitling chronograph vouch for this.” In the same ad, Willy defines his credo, “when a man puts on his watch, the world may see in this, his most treasured personal possession, the unmistakable stamp of impeccable taste.”

OPPOSITE: Willy Breitling and his wife Beatrice ca. 1951

THIS PAGE: The 1946 catalog details the range of chronograph scales available

REFS. 762, 764, 766, 784, 785, 799, 800, 804, 805

Willy’s next chess move: complications. The rattrapante, used to record multiple time intervals with its split-second hand, was (and still is) the highest complication you could add to the chronograph. It had been central to the company since 1900, when Leon Breitling proudly advertised his new models. Willy sought to build on his grandfather’s legacy by taking the split-

second out of the pocket and onto the wrist. But this was the 1940s; Breitling was an industrial manufacturer now and couldn’t hand build ebauches like Leon did. The only available industrialized split-second standard ebauches were designed for pocket chronographs. The Valjoux 55VBR, used by Breitling for its wide selection of pocket rattrapantes

OPPOSITE:

Duograph ref. 764, 1945, Venus cal. 179, 38 mm case: 18k gold, hands: Pencil

THIS PAGE:

1937 advertisement for the Breitling ref. 612 pocket chronograph rattrapante

ABOVE:

(sometimes called “split chronographs” or “doppelchronographs”), was much too large for the elegant wristwatches that Willy had in mind. Venus and Breitling had been working on their own version for years, a family of rattrapantes that would fit watch cases from 36 mms upwards. These calibers had it all: split-second functionality, combined with twin- (cal. 179) and triple-register (cal. 185) base movements, all in wrist-optimized sizes.

Seizing on the promise of this ready supply of ebauches, Willy proudly showcased his new “Duograph” rattrapante models in the 1940 Breitling catalog. But this technological breakthrough apparently came with some teething problems (perhaps literally) because it took another three years for the Duograph to enter mass production. When it did, however, Willy cheekily announced it in an ad that showed it “growing” out of the 1940 catalog.

A first model, the non-waterproof 36 mm ref. 762, launched in early 1943, was soon followed by the larger waterproof ref. 764 at 38 mm. Very quickly

after, a triple-register model was launched under references 766 (from 36 mm) for the non-waterproof and 791 for the waterproof. The latter came in what were roughly 38 mm steel cases, considered huge at the time. While the twin-register ref. 764 was made in solid gold, the ref. 791 was surprisingly never documented in precious metal. These pieces, housed in beautifully sculpted cases with mesmerizing dials, continue to be wonders of watchmaking.

The Duograph was the cornerstone of Willy’s strategy to wrist-size the rattrapante, but it remained a very rare bird. Breitling only produced 350 Duographs, including all references, over its production period from 1943 to 1970, and most were custom made.

One particular model, the ref. 800, a rattrapante with moonphase and date, which first appeared in the 1946 catalog, was for many years never seen in reality until one surfaced about a decade ago, branded by U.S. retailer Tourneau. You’ll see another example of a rediscovered ref. 800 later in this chapter.

Breitling’s

ABOVE: family of rattrapantes in 1944

OPPOSITE:

Duograph ref. 762, ca.

1943, Venus cal. 179, 35.8 mm case: steel, hands: slim Lozenge

THIS PAGE:

Duograph ref. 762, ca.

1943, Venus cal. 179, 35.8 mm case: steel, hands: Leaf (feuille)

NEXT PAGE, LEFT:

Duograph ref. 766, ca.

1944, Venus cal. 185, 35.1 mm case: steel, hands: Pencil

NEXT PAGE, RIGHT:

Duograph ref. 764, ca.

1944, Venus cal. 179, 38.1 mm case: steel, hands: slim lumed Syringe

OPPOSITE:

The final complication Willy saw waiting for chronographs in the post-war boom market was the full calendar, with day, date and month. Breitling’s competitor at the time, Angelus, had already launched a full calendar chronograph in 1942.

So by 1944, when Venus had not yet completed its version of the complication, Willy forged ahead using Valjoux-based calibers—the twin-register (cal. 23C) for the Breitling ref. 784, and the tripleregister (cal. 72C) for the Datora ref. 785. Breitling was one of the first to use these movements.

By the late 1940s, the Venus full calendar calibers had finally arrived, starting with the cal. 191 that replaced the Valjoux 72C. The even more complex Venus cal. 187 would go on to power the subsequent Datora ref. 799, which added a moonphase surrounded by a pointer date, along with an hour counter.

The next Datora to launch—references 804 (waterproof) and 805 (nonwaterproof)—needed to be Valjouxbased once again to add the moonphase display at 6 o’clock, in combination with a pointer date, day of the week, month and hour counter.

A recent lucky find is the only known solid-gold ref. 800 a split-second chronograph with a date display and moonphase. It is based on the Venus cal. 195 that was hugely complex for its time, and still is. These watches were manufactured in such small quantities that, according to production ledgers, no reference-specific gold cases were ever made for them. Instead, this one piece was installed in a 1944 18k gold case made for the Duograph ref. 766, hence it is listed with both references.

I have yet to see an example of the ref. 800 cased in one of, what the ledgers report, was a 1951 delivery of 20 ref. 800 steel cases. The only models that have surfaced up until now have been Duograph-reference cases and two examples of the moonphase and date Chronomat ref. 801 upgraded with the rattrapante caliber 195. Interesting to note that the ref. 800, despite being a combination of date, moonphase and rattrapante, was placed in the Datora section of the 1946 catalog. These complicated wrist chronographs accomplished what Willy set out to do: distinguish Breitling through the superior technicality of its offering. A checkmate in his conquest of the chronograph market.

OPPOSITE:

Datora ref. 799, 1947, Venus cal. 187, 34.9 mm

case: 18k gold, hands: Lance

THIS PAGE, TOP TO BOTTOM:

Tourneau Datora ref. 799, 1947, Venus cal. 187, 34.6 mm case: steel, hands: Javelin

Datora ref. 799, 1947, Venus cal. 187, 34.7 mm case: steel, hands: Pencil

OPPOSITE:

While there are only two model references in this range of Premier chronographs, the ref. 765 and its twin-register sibling, the ref. 777, they are incredibly important for Breitling and chronograph evolution in general. They began as tool watches, built for wartime military precision. Their cases were waterproof, designed for pilots and soldiers who faced all kinds of unexpected situations. And at 38 mm, they were huge for their time, with simple, functional dials that were easy to operate and easy to read at a glance. But while their roots in the 1940s were as air force chronographs, in the post-war years these watches would evolve on the wrists of athletes, adventurers and businessmen into elegant gentlemen’s chronographs.

The triple-register ref. 765 was one of two references to be carried over from the Landeron Hahn caliber period before 1940

Huit Premier ref. 765, 1946, Venus cal. 178, 38.1 mm case: steel, hands: slim lumed Syringe

(the other being the ref. 734, covered in the non-waterproof section of this book). It was the “tool watch par excellence” made by Breitling’s Huit Aviation division, which was also producing cockpit clocks and chronographs, along with professional pilot’s watches. These watches contained the best calibers money could buy, and they were tested for reliability in temperatures from -40 to +100°C and on specialized vibration tables that mimicked the punishing conditions inside a warplane. When Breitling discontinued the use of the Hahn cal. 42, the ref. 765 migrated to the new Venus-based movement line. The 38 mm watch was designed to hold the 14-lignes Venus cal. 178, but because the movements were late to arrive, early models were assembled using spacer rings with the smaller, 13-lignes Venus caliber 152.

The ref. 777 with its approximate 38 mm diameter was a prime example of Breitling’s progression from function-with-purpose to function-with-style. What started out as a robust, comfortable, easy-to-read tool watch evolved into elegant chronographs with an almost endless variety of dial options and case designs, including solid 18k gold screwback cases.

Of all the Premier models, the 777 was offered in the widest range of designs. Most of the options and combinations of functions, cases and dials mentioned in archived catalogs were applied to the 777. A chronograph could have a tachymeter or telemeter scale, a pulsation scale for doctors or a decimal scale for industrial production. It might have applied indexes, lumed indexes, painted indexes, Arabic or Roman numerals. The dials could be white, chamois, champagne, cop-

per, salmon, gold, black or brown. It also featured chimera dials, which were made with a special dial polishing and printing method that makes colors and patterns appear, disappear or change intensity under different lighting.

Even for longtime Breitling collectors like myself, it is still possible to find these models in new and surprising combinations. I’m still looking for the next, still unknown, beautiful dial on a Premier 777.

OPPOSITE:

Premier ref. 777, 1945, Venus cal. 178, 37.4 mm case: 18k gold, hands: Pencil

THIS PAGE:

Premier ref. 777, 1945, Venus cal. 178, 37.4 mm case: 18k gold, hands: Pontif

“The Premier Story is very much the history of the chronograph, as any book about Breitling must be,” writes author Fred Mandelbaum, Breitling’s foremost collector and brand historian, of the company that defined the look and function of the chronograph we know today.

Breitling’s three generations of founders each played their part in shaping it. Leon Breitling patented the mechanism that would make his pocket chronographs manufacturable for the masses; his son, Gaston, introduced the first wrist-worn version with an independent pusher at two o’clock; and his grandson, Willy, patented the second independent pusher at four.

Willy Breitling would then take his family’s legacy even further, ushering in the chronograph’s golden age. From the 1940s onward, he used his vision and marketing savvy to reinvent the wristwatch for the glamorous tastes of his era. Perfected in form and imparted with horology’s most demanding complications, his Premier, Duograph and Datora lines would take the chronograph from purpose to style.

Captured in exquisite photography, including rarely seen archival pieces, and featuring a comprehensive dating-and-authentication guide for collectors, this third installment of the WATCH STORIES series follows the Breitling Premier’s journey, from its roots in the pocket chronograph to its lavishly appointed iterations in the 21st century.

A Moon Watch Story – The extraordinary destiny of the Omega Speedmaster

Navitimer Story – The epic saga of the Breitling chronograph

Premier Story – Breitling Premier, Duograph and Datora

ISBN 978-2-940506-