17 minute read

Discussion

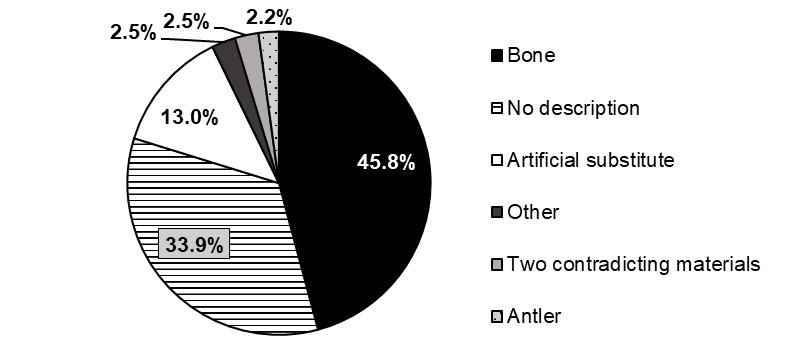

The largest proportion of covert items listed were described as bone (45.8%, n= 127), including ‘bovine bone’, ‘cow bone’ and ‘ox bone’. For 33.9% (n = 94) of covert listings, a description of the material was not provided. The next most frequent category was artificial substitutes (13.0%, n = 36), comprising of ‘ivorine’ (an artificial product resembling ivory), ‘Bakelite’, ‘resin’, ‘acrylic’ and ‘celluloid/simulated ivory’. For 2.5% (n = 7), the material was described as two contradicting materials, such as ‘horn/bone’ and ‘ivorine/bone’ and a further 2.5% (n = 7) of sellers identified another material such as ‘porcelain’ and ‘tagua nut’. Six vendors (2.2%) said the material was made from antlers.

2.5% 2.5% 2.2%

Advertisement

13.0%

33.9% 45.8% Bone

No description

Artificial substitute

Other

Two contradicting materials

Antler

Figure 3. The percentage of material descriptions used for covert ivory listings.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Value of the online ivory market

Over the 31-day period, 1,832 ivory listings collectively worth over one million pounds were identified. These figures are likely to underestimate the value as eBay items were often recorded when they had just been listed with a low starting bid and the lower estimates from the auctioneers were recorded.

The results showed that 84.2% of the 1,128 items being offered for sale through Barnebys with a known value had a guide price of under £500, whereas Lau et al (2016) found that only 42% of the 420 items on Barnebys had a guide price under £500. This could mean that either auction houses are pricing ivory items at a lower price, or a higher proportion of lower value items are coming to market. However, this difference is more likely explained by Lau et al (2016) recording the uppermost estimate in a price range instead of the lower price, as in the current study. This is supported by Two Million Tusks (2017) finding that 91% of ivory pieces sold at auction for £400 or less shortly after Lau et al (2016)’s study.

The range of prices was higher in the current study. Lau et al (2016) found that the item with the highest guide price was a table cabinet made from a mix of materials being auctioned with a guide price of £20,000–£40,000. The current study found eight items with a guide price exceeding £20,000, five of which exceeded £40,000, the highest being a sword with an ivory grip being advertised by Wick Antiques at a fixed price of £125,000.

4.2. Volume of the online ivory market

Over the 31-day period, 331 listings were identified on eBay, 263 of which were covert. In comparison, during a two-week period in 2011, IFAW (2012) identified 39 listings on eBay UK containing ivory and Alfino and Roberts (2020) found 84 ivory listings on the same website from 18 January to 5 February 2017. Taking into account the varying length of the investigations, the current study found significantly more ivory items on eBay than the previous investigations. Although this could demonstrate an increase in the amount of ivory being sold online in the UK, these differing results may also be explained by the different keywords and search refinements used.

For this study, the word ‘ivory’ was always searched first, with unique results from other keyword searches supplementing these results. Of the 331 eBay listings, 251 (76%) were only found by searching words other than ‘ivory’, such as ‘netsuke’ and ‘bone’. These numbers are still under-representative as more results would have been produced if the searches were not confined to ‘Antiques’ and ‘Collectables’, as it is likely that sellers list ivory under other categories such as ‘jewellery’. Whilst eBay has blocked a number of listings and is attempting to combat the problem (Walker, 2021), the findings suggest they are still failing to effectively tackle the issue.

Lau et al (2016) found 56% of ivory items available at physical markets were figures, 26.8% were household goods, 9.5% were jewellery and the remaining 7.7% were personal items. In comparison, the current study found that items consisted of 43.6% figures, 31.8% household good, 21.6% personal items and 3.0% jewellery. Although ornaments remain the most common type of item available to buy, it appears that a larger proportion of household goods and personal items are available online. These item types, on average, are significantly more valuable than figures and jewellery.

During a survey in April 2016, Lau et al (2016) identified 695 ivory items across both Barnebys and The Saleroom (another auction search service). In the space of a month the current study found approximately double the number of ivory items (n = 1,399) on Barnebys alone. Although Lau et al (2016) excluded items which stated that they were made from non-elephant ivory and did not collect information over a month, there is no indication that the introduction of the Ivory Act in 2018 has deterred any auction houses from selling ivory.

The day of the week chosen to sample data may impact the number of ivory items found in investigations, as a high number of listings were identified on Monday mornings. This suggests that either Sunday daytime or early Monday morning may be the most popular time for auctioneers to advertise their lots.

4.3. Enforcement of regulations

The figures include items which contain any amount of ivory, meaning that trade in some of these items may still be permitted under exemptions once the Ivory Act is implemented. However, this is likely to be a small percentage, as 22.9% of items for sale were deemed to not have ivory as the primary material (less than 50% of ivory) only a proportion of which would contain less than 10% ivory, in which case they may be exempt under the Act (DEFRA, 2021). Musical instruments containing less than 20% ivory by volume and pre-1918 portrait miniatures with a surface area of no more than 320cm2 may also be exempt under the Act. Some items offered for sale might also fall into the exemption under the Act for pre-1918 items of outstandingly high artistic, cultural or historical value (DEFRA, 2021).

These items did not form a significant part of the data as only 106 listings were ‘paintings’ and nine were ‘musical instruments’, some of which may already be exempt for having less than 10% ivory by volume. Not all of these items would be exempt, but assuming they all did meet the type, ivory volume, size and date exemption requirements, this would form 6.3% of all listings. Items which were either musical instruments, paintings or deemed to be less than 50% ivory, make up 498 of the listings, meaning that the maximum possible percentage of listings that would qualify for exemptions is 27.1%. However, as discussed, the actual number of exempt listings is likely to be significantly lower. This leads us to conclude that delays in implementing the Act have allowed continued domestic and international trade in large amounts of ivory which will be illegal to trade once the Act is implemented.

It is likely that some of the ivory would be illegal to sell even under current regulations, as recently-poached ivory continues to be sold across Europe (Avaaz, 2018). The current study supports the view that the banning of post-1947 ivory has not been effective in preventing more recently poached ivory from entering the UK market. There was one fly swish on eBay which was likely to be ivory, despite claiming to be bone (faint Schreger lines, no evidence of the pitting which is seen on bone), and it was inscribed ‘A gift from the people of Tanzania 1967’. Therefore, not only have delays in implementing the Act allowed large quantities of items to be traded but have also continued to enable the trade of illegal ivory.

4.4. Finding ivory items online

The results were limited by the search refinements used. Antiques Atlas had few daily uploads, with an average of one upload every three to four days, but not every item containing ivory would have been put under the ‘Ivory Antiques’ category. A general search for the word ‘ivory’, as with the other two websites, would have produced more results.

Searches for ‘faux ivory’ did not produce unique results on any of the websites, despite previously being identified as a codename for ivory (IFAW, 2012; Harrison, Roberts and Hernandez-Castro, 2016) and no listing on the database explicitly used this term to describe the material. This was the only keyword that was not responsible for finding any of the listings on the database. This may show that the use of code words changes over time in order to evade detection.

It may be that the word ‘ivory’ is avoided by sellers altogether, as these listings could be automatically flagged to monitors. It was noted that some listings which were deemed to not be made from ivory still used the spelling ‘iv0ry’ (using the digit zero) when describing the item’s colour or the vegetable ivory material. This presents further challenges in efforts to find ivory listings.

Searching for ‘teeth’ antiques on eBay produced eight teething rings and sticks made of ivory that were covertly listed. Although the purpose was to find items made from teeth, this suggests that covert ivory may be more often found by searching for items that are often made with ivory, such as netsukes.

4.5. Identifying covert ivory

Although eBay was only responsible for 18.1% of all identified ivory listings, the majority of its ivory items were covert (Figure 2). As a recent study also found (Venturini and Roberts, 2020), ‘bone’ was the most popular material description used for ivory items on eBay (Figure 3). The number of ivory items being sold as bone is likely to be even higher because some ‘bone’ items could have potentially been made from ivory, but this could not be verified from viewing the images provided, either because of the image quality or the way it was carved (such as with “bone” inlaid boxes and knife and fork handles).

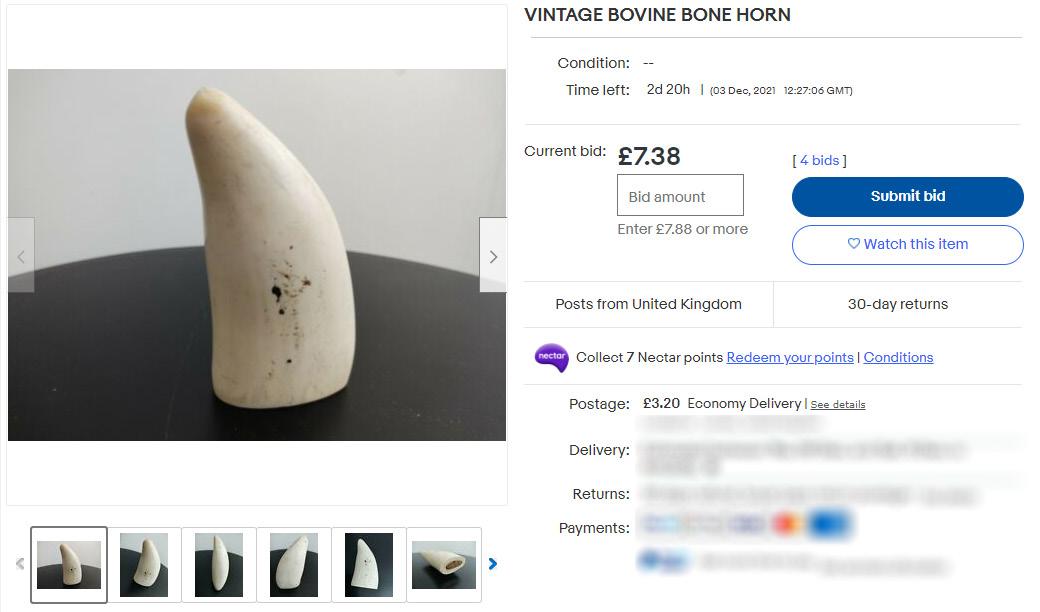

Image 1. A sperm whale tooth being listed on eBay as ‘bovine bone’.

Approximately 20% of covert ivory sellers on eBay encouraged the careful examination of or the zooming in on all images, without referencing a particular feature or damaged part of the item. This indication of covert ivory has been previously identified by Baker et al (2020).

Other tactics included photographing the item on scales to demonstrate its weight, photographing the item with light shining through it and describing the material (eg ‘Carved from a hard white/cream material’ and ‘Taps hard like stone but looks a bit varnishy. I have applied heat and it doesn’t melt. Weighs 51 gm’.) IFAW (2012) also found that in 2011, sellers on eBay would imply the material was ivory without explicitly stating that it was, for example by referencing items as ‘being cold to the touch’. This study demonstrates that, a decade later, eBay sellers are still able to sell ivory using this same tactic.

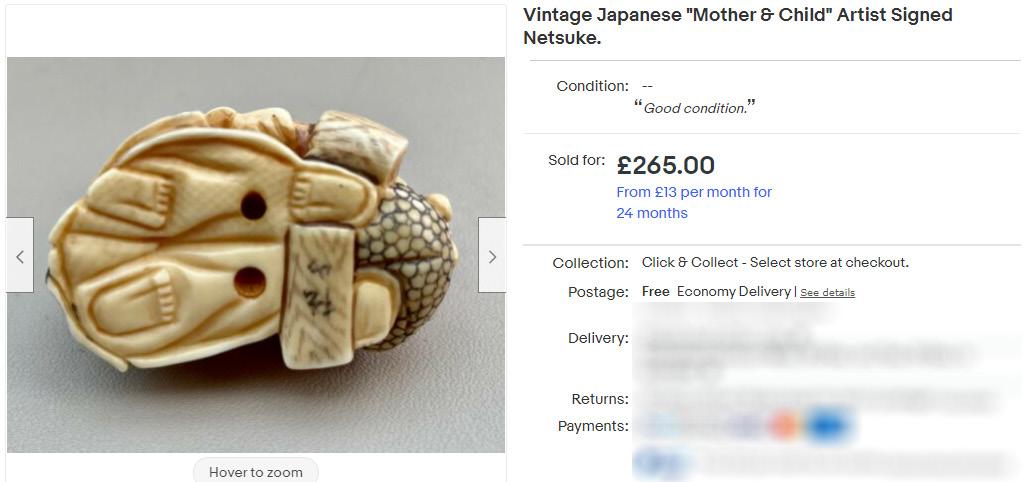

Image 2. An example of a covert ivory listing. The primary material was selected as ‘ivorine’, but the clear Schreger lines indicate that it is elephant ivory.

It may be that some sellers were genuinely unable to recognise the items as elephant ivory. However, it can be assumed that the majority of sellers were being purposely deceptive to avoid their listing being removed, as many eBay sellers were linked to a professional antiques shop. There were multiple occasions where the seller described their item as being made from a different material, but their personal website confirmed the item was made from ivory. For example, one seller listed three canes as being made from ivorine, but their own antique cane website described the same three items as being made from ivory. Another example was a Thomas Tuttell sundial priced at £3,750, with the plate being described as bone. The same item on their website had the exact same description except the plate was described as ivory.

Also, although the material was described in the item specifics as being something else, some listings admitted that the item was made from ivory in the description. One wrote ‘Made of the finest quality materials, German silver (a nickel alloy) the other which I cannot name here, is best left on the animals with trunks to which it belongs, but as it was made over a hundred years ago can be enjoyed for it [sic] wonderful silky smooth texture’. One eBay seller selected the primary material as ‘Mixed Material’ and wrote in the description ‘Please be understanding there is no disrespect of animal as is over 100 years so is antiques [sic] – Guarantee elephant teeth’. Two listings were even less subtle, as they selected the primary material as ‘bone’ and ‘acrylic’ but then described the items as ivory in the description. Many eBay listings contradicted themselves, for example, by saying the material is Bakelite in the description, but selecting the material as bone in the item specifics. Some also selected the material as being different materials eg ‘Ivorine/Bone’, ‘Plastic/Bone’ and ‘Horn/Bone’.

Two covert eBay listings put in their description ‘Important note to eBay team: This item does not contain any animal or part of an animal of a species listed in Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act, or the Schedules to the Wildlife Acts 1976-2000. Nor does this item contain any animal or part of an animal of a species listed on Annex A of the EU Wildlife Trade Regulations. This item has been checked against the Annex A or B list of the EU Wildlife Trade Regulations and has been confirmed that it is able to be exported from the EU without a permit. Item is crafted from bone deriving from a bos taurus (cattle).’ One of these listings contradicted themselves by describing the ivory netsuke as bone in the description but selected ‘ivorine’ as the primary material.

4.6. Identifying the ivory-bearing species

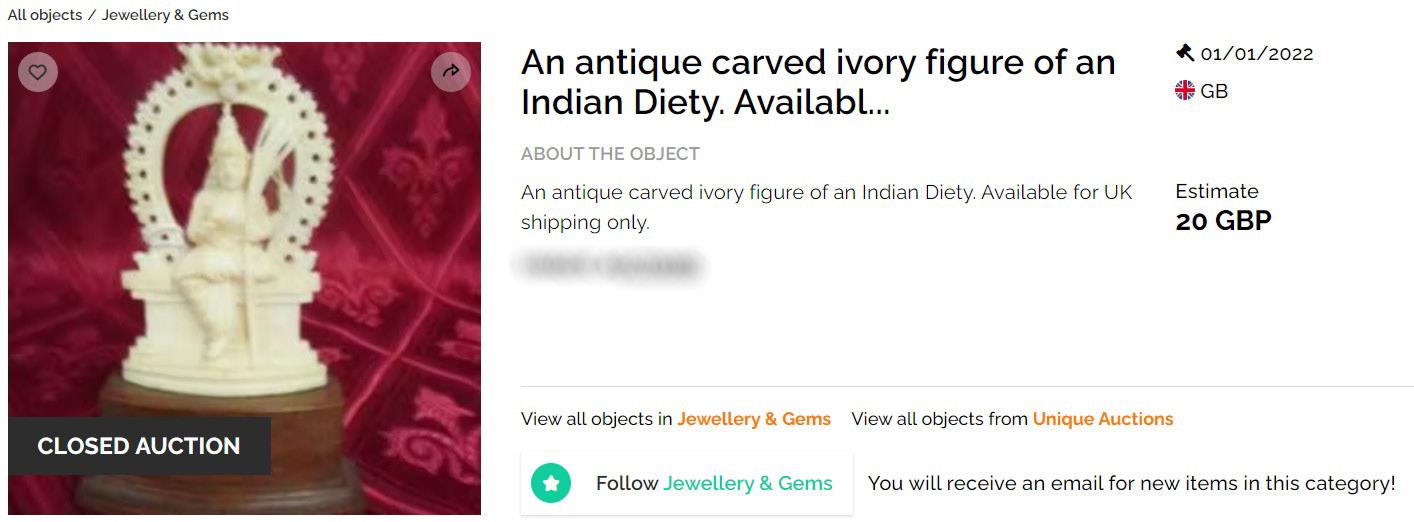

The findings complement those of recent studies as elephant ivory was the most common species identified (Yeo, McCrea and Roberts, 2017; Parry, 2021). However, numbers of items made from elephant ivory may be much higher because it is the easiest ivory material to identify from online images as Schreger lines are visible from more angles and are more prominent than other markings. There were five listings where the species could not be identified, but the material was described as ‘marine ivory’, suggesting it was made from either hippopotamus, whale, orca or walrus ivory (IFAW, 2004). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that a portion of the listings from an unknown species is ivory from non-elephant sources. The biggest limitation of the study was the lack of clear images from different angles, preventing confident identification of ivory or the ivory species.

Image 3. An example of an overt ivory listing on Barnebys. The poor quality of the image, even when viewed in full on the auctioneer’s website, meant that the species of origin could not be determined.

After the data collection and analysis period, we were made aware that 19 listings which featured in our database were physically inspected by an expert. While the items were described as ‘ivory’ and the species from which they were derived were not disclosed, the expert identified them as being derived from elephant, sperm whale, walrus and hippopotamus. Although the current study determined that nine of the listings featured either elephant or walrus ivory, the species for the remaining 10 were unknown. This supports the assumption that a significant portion of the ivory items from an unknown species are derived from non-elephant sources.

Nearly one fifth of identifiable items were determined to be from non-elephant sources (Figure 1). Although DEFRA’s call for evidence suggested that the UK is not of major importance in the trade or market of nonelephant ivory (DEFRA, 2019), the findings of this study challenge this. One investigation found a total of 899 hippopotamus, mammoth, narwhal, whale, walrus and warthog ivory items were sold by auction houses from 2013 to 2019, with an additional 20 having a mixture of species and a further 630 not being fully identified but labelled ‘marine’ (DEFRA, 2019). The current study suggests that this is a huge underestimation of the scale of the non-elephant ivory market in the UK.

In one month, 120 ivory listings were confidently determined to be from non-elephant species (including five listings that were not fully identified but labelled ‘marine ivory’) using online images. Scaled up, this would equate to 8,640 non-elephant ivory items in roughly six years. Unless the methodology for the previous investigation severely limited the number of ivory items that could be identified, the most plausible explanation for the disparity is that the demand for non-elephant ivory has significantly increased since 2019. It cannot be ruled out that the proposal to ban elephant ivory has already shifted demand towards items made from non-elephant ivory-bearing species, especially as auctioneers have reported an increasing interest in hippopotamus ivory as an alternative to elephant ivory (Horton, 2019).

Although hunting for ivory has not yet been identified as the main conservation concern for all non-elephant ivory-bearing species (IFAW, 2020), banning the sale of ivory from these species should still be considered as a conservation measure and it would also help ensure rigorous and effective enforcement of the legislation designed to protect elephants.

No animal-identifying features were visible in over two thirds of all ivory listings, demonstrating the difficulty in distinguishing the ivory species from online images. There were many items that contained more than 10% ivory, but the style of the item, coupled with the lack of clear images focusing on the ivory components, meant that the animal-identifying features were not visible. Even if the images were viewed by experts, the quality and lack of angles make confident differentiation impossible for some listings.

If only elephants are protected by the Ivory Act 2018, then it is likely that sellers will continue to sell elephant ivory under the guise of it being ivory from a different species that remains legal to trade. Even if Schreger lines are visible in the images, sellers may claim that the item is made from mammoth. The trade in alternative legal ivory, such as mammoth ivory, has the potential to perpetuate demand for elephant ivory (Wildlife Justice Commission, 2021a).

There are also concerns that the legal trade of non-elephant ivory could put strains on the already decreasing populations of other ivory-bearing species (Andersson and Gibson, 2017; BBC, 2021; Moneron and Drinkwater, 2021). Therefore, a precautionary approach involving banning the trade in ivory from all relevant species is important to ensure the protection of both elephant and non-elephant species.

The non-elephant species discussed in this report have already been identified as being at risk of being poached for their ivory, but it is unlikely that all at-risk species can be predicted prior to the enforcement of the Act. Although other ivory-bearing species may provide a more obvious alternative to elephant ivory, other animals may still be at risk of exploitation. For example, helmeted hornbills (Rhinoplax vigil) are being increasingly targeted by hunters as their casque is used as an ivory alternative (BirdLife International, 2020; Ouitavon et al, 2021). Also, it has been recently reported that giant clams (Tridacna species) are being overexploited in response to China’s elephant ivory ban, which is having a devastating impact on their marine habitat (Wildlife Justice Commission, 2021b). Governments need to identify and respond to reports of other species being exploited to provide alternatives to elephant ivory.

4.7. Conclusion

New advertisements for ivory items are being uploaded on online UK trading sites every day, with sellers continuing to find ways to evade detection on platforms where selling ivory products is prohibited. The delays in implementing the Act have meant that thousands of ivory items have continued to be sold, perpetuating the demand for ivory, and further endangering elephant populations.

Identifying ivory products from online listings can be difficult, but determining the ivory-bearing species is particularly challenging due to the limited number of images, poor image quality, inability to view the item from certain angles, and limited or deceitful text descriptions. The Act currently only prohibits trade in ivory from the tusk or tooth of an elephant (DEFRA, 2021). If the regulations are not amended to include other species, then there are two likely outcomes: Elephant ivory will continue to be sold under the guise of it coming from other species, especially mammoth if Schreger lines are visible; and non-elephant species will be more at risk from exploitation due to a shift in demand away from elephant ivory to other, legal alternatives.

Considering the delays that the Act has already faced and the increase in the popularity and trade of nonelephant ivory observed, a preventative approach rather than reactionary changes is of the upmost importance to the conservation of elephant and non-elephant ivory-bearing species and effective wildlife law-enforcement.