Bossy

Chimera

The ANU Women’s Department Magazine Edition 8 November 2022

Bossy would not exist without the ongoing support of the ANU Women’s Department. We thank them for their boundless generosity, and for their commitment to the safety and wellbeing of the members of our community.

Edition Eight was partially funded by the SCRIPT grant.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Bossy is sourced, edited, printed, and distributed.

We pay our respects to Elders; past, present, and emerging. We also acknowledge that this land—which we benefit from occupying—was stolen, and that sovereignty was never ceded.

Within this ongoing echo of colonialism, we commit, going forward, to do better in amplifying the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within our community.

We also commit to ensuring that the incoming team for 2023 honours the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories, and stands by their right to recognition.

1

Letter From the Editors

Dear Readers,

The Chimera was a fire-breathing creature with the head and body of a lion, a goat’s head on her back, and a serpent for a tail. She is often depicted as a near-invincible monster who devastated the land around her home until she was slain by Bellerophon’s lead-tipped lance. Even among ancient writers, her story was mostly relegated to a couple of sentences—no one knew how to slay her, The Hero captures a flying horse… you get the idea. Rather than a source of intrigue for storytellers, the Chimera was mostly viewed as an object of visual inspiration because it was a hideous and spectacular deformity—an intolerable monster suspected to represent the fears of its audience; fears of a being that seemed to disobey normative roles, to intermingle identities. Even today, the Chimera reminds us that nothing about ourselves is set in stone.

Many of us can perhaps relate to this conception of Chimera as a malleable body to be scrutinised or gawked at— Homer’s “bane to man”, rather than a being deserving of basic kindness. Yet in her story, the Chimera cannot really be ignored. She is immense, grimacing, encircled by roaring flames; fully herself and emanating life despite her nearimpossible incongruity. Following on from edition seven, Memento Mori, we have decided to give new life to an ancient legend by inhabiting this so-called monstrosity; in doing so, we collectively aspire to give voice to our unseen or improbable experiences and feelings. We remember death: now, how do we go about coping with life—this fantastical, terrible existence? And how do we define ourselves, particularly when we have limited control over how we are experienced? This edition of Bossy invites you to celebrate your connection to the world and to stories—to reinvent your flaws as your strengths, and to reflect on this tumultuous life, its wonderment and horror.

Another, newer definition of the word ‘chimera’ is an imagined thing: something fanciful, improbable—impossible to achieve. This year, we have watched in horror as institutions prioritised the systemic perpetuation of bigotry and oppression over the welfare of its people. The world is bleak—it’s justifiable to feel nihilistic about the future, to think that our dreams are little more than a fantasy. Perhaps we must reimagine our goals as intersectional feminists if we are to enact the change we desire: as Avan—our own Women’s Officer—writes, being a demon bitch about feminism and injustice is to reject complacency. Perhaps it is not enough to accept chaos—perhaps we must radically redefine it, throwing normative frameworks of white, heterosexual, cisgender, patriarchal neo-colonialism into tumultuous question as we fight to be heard above the increasingly insidious tide of conservatism, both around the globe and closer to home. In light of the repeated transphobic incidents across our campus this year, we particularly reaffirm our solidarity with transgender and non-binary students: you will always have a voice with us.

We want to thank our contributors for dedicating their immense energy and creativity to the development of edition eight. In reading this edition, you are sure to be inspired by the pride and courage with which our community have bared their souls, attempted to understand the complexity of their inner workings, and invigorated lost and untold tales—their words are a source of endless intrigue and empowerment. Thank you to our wonderful team: the magic of this edition was born from your many hours of labour, care, and spirit. Thank you to Avan and the Women’s Department for their endless support throughout the year—and we give tremendous thanks to you, reader. There is no Bossy without you.

Within this magazine, you will find writers and artists who have recreated the reality of experience through fictional, or even “dishonest” expression—unusual forms of storytelling, creative memoirs, and poetry. The diversity of our contributors’ stories invites you to share in the chaos that exists in all of us, to admire our strength and versatility, and to allow your own fiery tongue to spark and storm upon prejudice and hate; to build genuine empathy and allyship in a world that does not very often encourage the strength inherent to collectives. It is painful and terrifying to be ourselves—but there is also power to be found in the embracing of monstrosity. So, bare your teeth, and let your own hybridity carve out the beginnings of a brighter future. Perhaps it may appear improbable— but nothing is ever really impossible.

With love, Hengjia

2

Liu, Alisha Nagle, Harriet Sherlock, and Cinnamone Winchester

3

Avan Daruwalla

2022 ANUSA Women's Officer

A huge congratulations to the Bossy team for another year of incredible content, thoughtful pieces, and magnificent design. The ANU Women’s Department is a space in which we can’t always focus our time and energy on thriving (because we are sometimes focused on simply surviving), so when a creative outlet like Bossy produces something so special—it is truly something to celebrate. With so many talented and clever women and gender diverse people contributing to a shared vision, it’s no surprise that our very own feminist publication has grown to become so successful and is so valued by the community.

This is my second year as Women’s Officer, and I continue to be beyond honoured to work alongside so many strident feminists and passionate young people. Having such an engaged and invigorated Department and Collective has made for an incredibly productive year; with the launching of our birth control subsidy, the Too Little Too Late protest, the Follow Through ANU campaign, the introduction of regular feminist consciousness raising circles, the success of ANU Women’s Revue, a tonne of social events, and now of course—the release of Bossy.

This past year, the Department has experienced a number of challenges in ensuring appropriate media engagements and portrayals of the significance of feminist activist efforts as well as holding media accountable to a standard of cultural awareness and sensitivity. As Women’s Officer, having to explain why students deserve better, or why lived experience matters, or even why gendered violence is a real problem has been eye-opening. Public attention and media representation of feminist issues has been proven time and time again to be imperative to seeing change. Without the threat of reputational damage for neglectful institutions and promotion of progressive radical feminist content, mainstream misogyny and disrespect will continue to dominate. This is just part of the reason I am so thankful for the existence of and team behind Bossy, and why we are so proud to support their work.

This role has been really rough, and I fear I am leaving it far less optimistic than when I entered it; however, it has also been the greatest learning experience and provided the most caring and supportive community one could ask for. Advocacy for the wellbeing and safety of oppressed students is a long-term fight that has produced slow and unresponsive change. But the resilience of survivors and advocates has produced real and meaningful outcomes. We as a collective have consistently come together to support one another and make change happen, a poignant reminder to the university and likeminded institutions that there is no excuse for deprioritising the protection of vulnerable community members.

We will always stand for intersectionality, respect, compassion, and a culture that rejects bigotry and embraces equity. I hope that those of you reading Bossy’s eighth edition feel inspired and emboldened to continue to radicalise your feminism, and—if you have the energy and feel compelled—to get more involved with the Department in whatever capacity feels right. We are always here for you.

In solidarity and love.

4

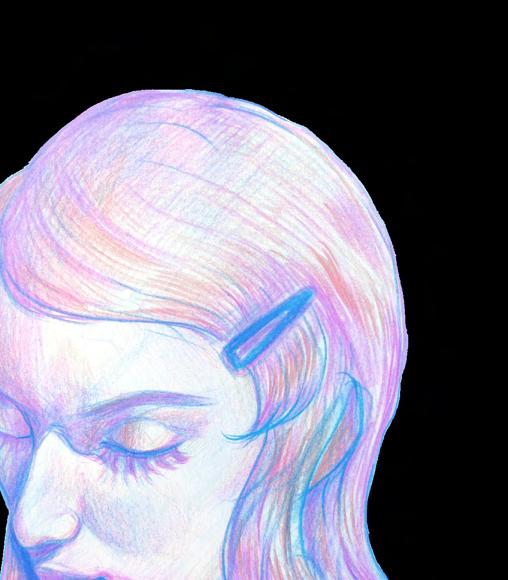

Sebastiàn Ungco Cover Artist

Sebastiàn Ungco is a student and multimedia artist primarily based in Metro Manila, Philippines. Heavily influenced by their deep love for modern cartoons and contemporary art movements, Sebastiàn’s works typically involve stylised color studies of tragedies and other epic celebrations of humanity which showcase their attraction to the delicate craft of story-re telling, with an emphasis on taking the ‘then’ and molding it into ‘now’.

This issue’s cover of Bossy features a South, Western, and South East Asian reimagination of a monstrous hybrid creature of Grecian myth called the Chimera. Inspired by the visual development art used to conceptualise fictional settings in films and video games, the cover hybridises the traditional imagery of surrealist and postmodern art movements to assemble an uncanny, collage-like landscape which encompasses the edition’s illustration of the absurd and hallucinatory. Equally influential throughout the design process was Sebastiàn’s love of adaptation— particularly The Legend of Zelda’s high fantasy storylines involving its world’s cyclical histories depicted in much the same manner as certain Hindu oral histories, and The Chronicles of Narnia’s vivid depictions of mythological hybrids.

Beholding the graceful Chimera as it soars through chalk pastel clouds and paper-cut moons, the themes of this year’s issue are epitomised by a vibrant sunset which paints dragon’s blood forests with dreamy hues of pinks and oranges. The transitory nature of the Chimera’s home functions as a visual epigraph, inviting readers to indulge in the transformative potentials facilitated by the contents of the magazine.

5

Peace and Victory Sebastiàn Ungco, 2022

I Had it Sorted Sebastiàn Ungco, 2022

Chronograph of 354 Sebastiàn Ungco, 2022

6

Acknowledgement of Country

Letter From the Editors 4 Letter From the Women's Officer Avan Daruwalla 5 Cover Artist Feature: Sebastiàn Ungco 10 Monsters Who Kill Men Kate Wood 13 Triformem Bestiam Alisha Nagle 17 Cornucopia: An Interview with Tisha Tejaya Lily Harrison 22 Pliny the Elder Attempts to Describe the Poet for His Natural Histories Bastian deBont 23 Self-Portraits Jamie Cardillo 26 Behind the Blog: An Interview with Samia Ejaz Christie Winn 28 A Reading Renaissance? Reviewing the Influence of BookTok Harriet Sherlock

30 Power, Self, and a Voice for the Voiceless: A Review of Madeline Miller's 'Galatea' Taia Apelt 32 The Brothel of Avignon Hengjia Liu 33 Sit Down, Stay a While. Pip Coddington 34 Vulgar Emma Crocker and Elspeth Rowell 36 The Dictionary of Lost Words Lily Harrison 37 The Dolmen Georgia Winzenberg 40 Watercolour Anonymous 42 Sarah Jamie Cardillo 43 Disintegration. Holly Ma 44 A Recurring Dream Alisha Nagle 45 MEDEA, the Body India Kazakoff

47 Identity Idiosyncrasies Faith Freshwater 48 Agitations Josephine Carter 49 Mystique and Quiet Illusions Olivia Gill 51 Cyclopes Have Feelings Too Alexandra Enache 52 Invasion Imogen McDonald 54 Study Partners for Sale Anna-Marieke Lechner-Scott 56 BeReal Lily Harrison 58 Held Adeline Higgins 60 One Time My Doctor... Luka Mijnarends and Mackenzie Francis-Brown 62 Growing Up Biracial Zoe Grahl and Erika Chaki 65 Reflections of a Would-Be Runaway Lucy Waterson 67 Only by Enduring Myka Davis

7 Contents

1

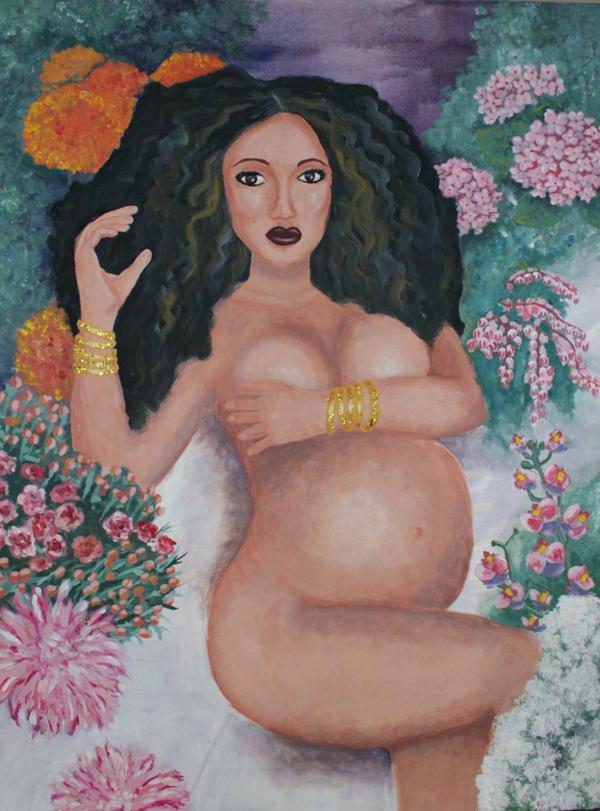

2

72 The Death of Koschei the Deathless Cinnamone Winchester and Sebastiàn Ungco 78 An American W-Wolf in London Zara Hashmi 79 The Good Girl Gone Bad: The Victorian "Madwoman" in the 21st Century Charlotte Stump 81 Perfume Imogen McDonald 83 Sub Rosa Lucy Sorenson 84 ‘I'm Glad My Mom Died’: Jennette McCurdy and Liberation Isabella Keith 86 Abortion Inaccessibility in a Post-Roe Australia Eliza Wilson 88 Mandy Sebastiàn Ungco 89 True Love Aveline Yang

90 Why We Need to Forget About Confidence Culture Eugenie Maynard 92 Prime Time Sydney Lang 94 Ode to Susan Cinnamone Winchester 96 Trapped C. E. Winn 97 Burn Her Mahalia Crawshaw 98 Clean Daisy Taylor-Reid 103 Bad Feminist Maddie Chia 106

No More Spiritual Bypassing: It's Time to Be a Demon Bitch About White Feminism Avan Daruwalla 108 Monstrosity: A Series of Haikus Anonymous 108 The Grotesque & Beautiful Gabriela Renee 110 Letters to My Inner Monstrosity Eugenie Maynard

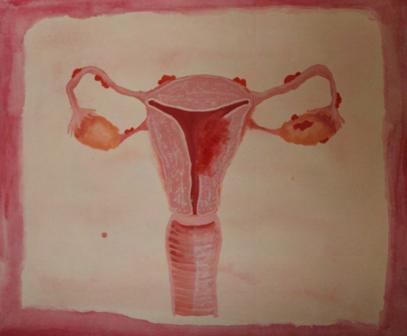

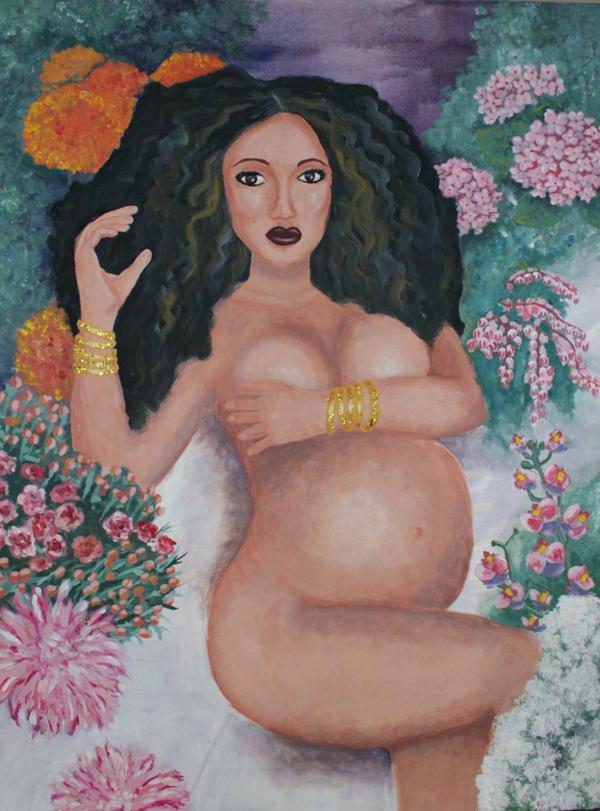

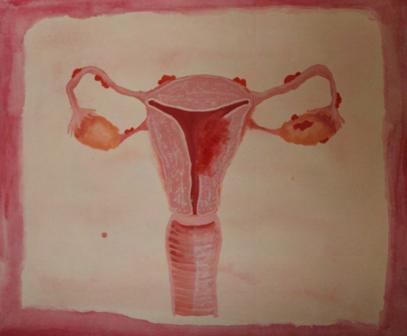

111 What I See When I Close My Eyes Olivia Kidston 112 The Redgum Ghost Jacqui Thompson 113 Arbiter Elegantarium Josephine Carter 114 Tribute to the Womb Madelie Joubert 116

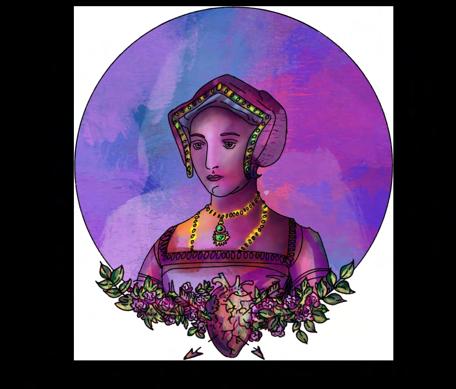

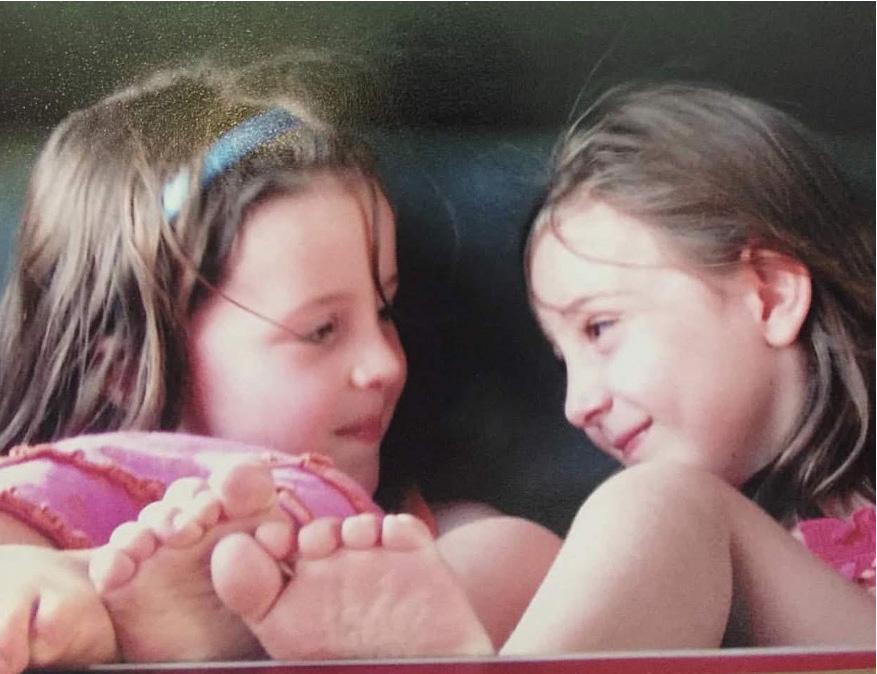

On Friendship: A Best Friend Interview Lily Harrison and Juliette Straughair 119 Henry VIII and the Histo-Remix Maddie Chia 121 Reclaiming Vanity Elentari Berryman 123

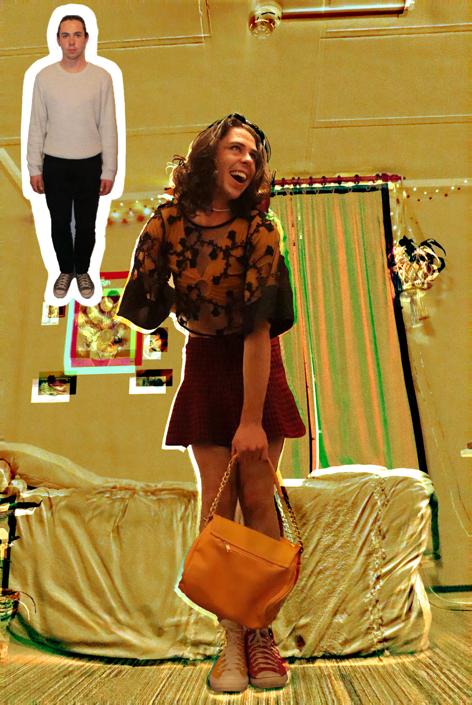

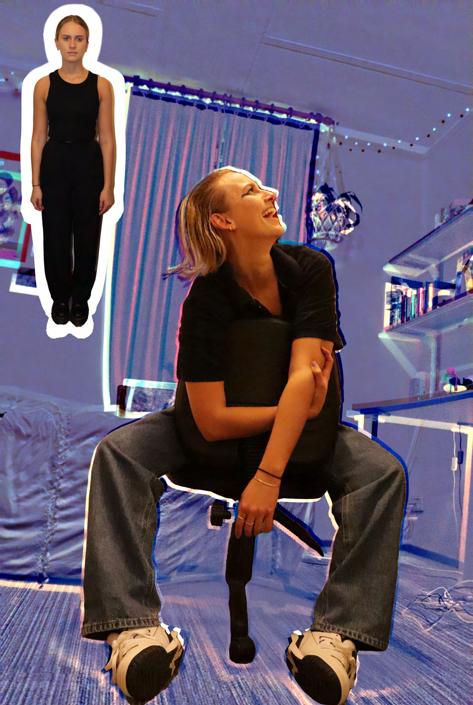

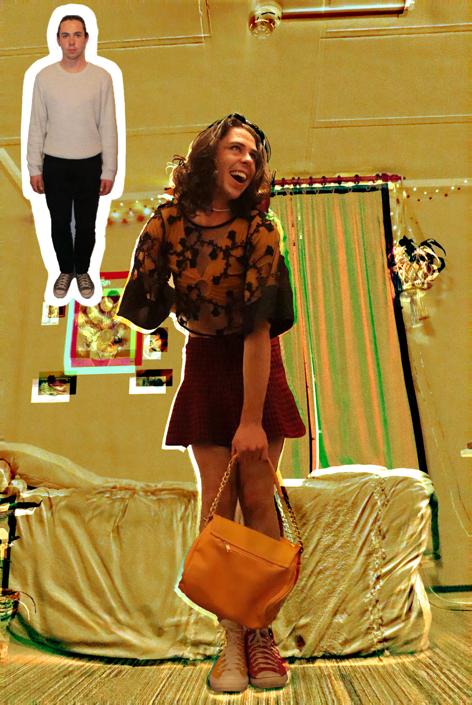

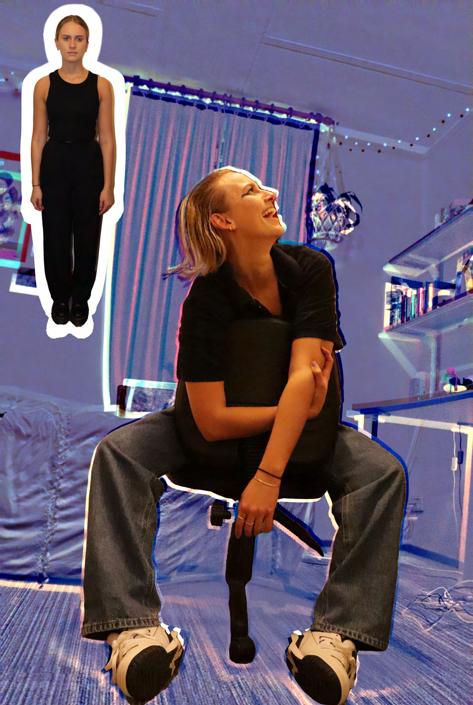

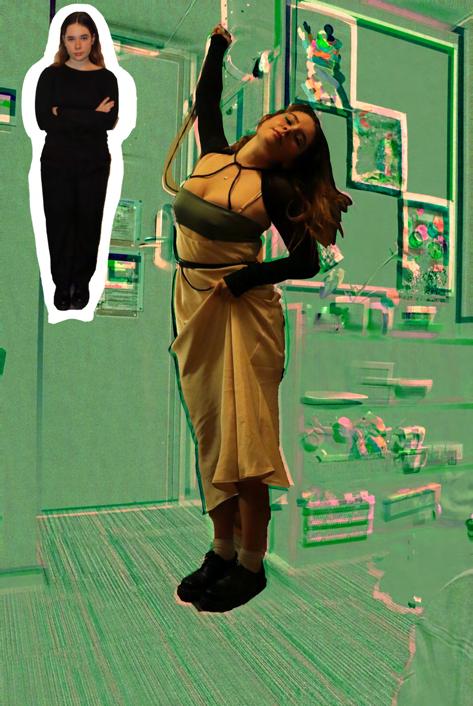

Self-Exhibition: A Photo Series Zoe Grahl, Zac McCarty, and Lucy Sorensen 126 Constructing an Ideal Self with a Virtual Body Sebastiàn Ungco

8

Section Designers:

Suhani Kapadia Hengjia Liu Alisha Nagle Harriet Sherlock Sebastiàn Ungco Cinnamone Winchester Christie Winn

k h i m a i r a

1. A fire-breathing shemonster in Greek mythology having a lion’s head, goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail.

2. An illusion or fabrication of the mind, especially an unrealisable dream.

—

“Women have always been monsters.”

Sady Doyle

Monsters Who Kill Men

Kate Wood

Kate Wood

10

CW: Discussion of sexual assault and abuse, trauma, death, violence, and murder.

Fairy tales are the stories we tell children to impart wisdom and to teach the “good behaviour” society expects. Little Red Riding Hood got eaten because she talked to a stranger. Cinderella gets her prince because she is good, obedient, and beautiful. Her stepsisters are ugly, cruel, and lazy, and they end up getting their eyes plucked out by crows. Myths and legends are the fairy tales of society—they instruct children and adults alike about cultural norms and expectations.

The monsters of myth, folklore, and oral histories can therefore tell us a lot about the values of the society that created them. Jess Zimmerman, author of Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology, describes feminised monsters as “the bedtime stories patriarchy tells itself.” The stories of feminised monsters and their journeys into monstrosity are perhaps indicators of how women are viewed culturally, their place in society, and “right” and “wrong” behaviour.

Monsters depicted as women feature in myths all over the world, and their origin stories paint a treacherous path to walk. Almost anything can turn a woman into an abomination. There are women transformed into hideous creatures as punishment for their sexuality or promiscuity; some are even punished because men have sexualised them without their consent. There are women who murder or lose their children, failing in the most fundamental role their society expects of them—the nurturing mother. There are monsters born of tragic women—women who died for love, in childbirth, or were murdered; there are monsters who carry the punishment of their husbands’ crimes. And what moral lessons we are to learn from such myths are not quite so clear as they once seemed.

We take folklore at its word when it tells us not to trust a monster—but are they really all that bad? Consider the Banshee. These Irish girls get a bad rap, but all they want to do is tell you someone in your family is going to die, and isn’t that ultimately helpful? Sometimes they are the spirit of a beautiful young woman who is sticking around to be the harbinger of death for her family, and other times they are horrifying old

women; but either way, they aren’t evil at all. They’re just sad ladies having a big old scream and I, for one, can relate to that.

My personal affinity with monsters began with Medusa. In older versions of the myth, Medusa and her two sisters were sea goddesses, born terrible and frightening with their snake hair and petrifying gaze. However, the Roman poet Ovid claimed a different origin story. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Medusa was a priestess who was famous for her incredible beauty, especially her hair. Neptune, the God of the Sea, raped her in Minerva’s temple. Afterwards, Minerva punished Medusa for being raped by turning her beautiful hair into snakes and making her gaze turn men into stone. She also wore snakes on her body—“creatures of her rage”.

But what if Minerva wasn’t “punishing” Medusa at all?

Growing up as an asexual teenager, I didn’t know what I was. I didn’t know there was a word for me. I just knew that I was different, and that something was wrong with me. The people around me knew I was different, too. Like at least 17 per cent of asexual people, I was a victim of corrective sexual assault. Between 16 and 18, my consent was violated repeatedly and often by men who genuinely believed it would fix something broken inside of me.

What I wouldn’t have given to have had snakes for hair! For Minerva to have given me a visage so hideous it turned men to stone would have been no punishment. To me, that would have been a blessing. As both a young asexual girl horrified by the concept of sex and a repeated victim of assault and abuse, Medusa’s punishment seemed to me anything but.

I didn’t tell anyone about the sexual abuse until I was 33. In the intervening years, I did not experience anger. I was frightened of others’ anger, and didn’t express it myself, because I didn’t understand it. I was not aware how much of it there was inside me, desperate to break out. My snake hairs were ingrown. It was painful, irritating, something I knew needed to come out—but I didn’t quite know how. Now I allow my snake hair to grow long. A friend once described me as “anger masquerading as a person”. I love my snakes, and I very much hope that a certain type of man fears me so much that he uses a mirror

to look around corners.

The famous Margaret Atwood quote, “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them”, aptly describes our gendered power imbalance both historically and today. It is interesting, in light of this reality, to examine the countless examples of beautiful feminised monsters who kill men in folklore. A shapeshifting spirit called La Siguanaba is said to haunt the waterways of many countries in Central America, with regional variations. General consensus is that they materialise in a body of water and appear from behind as a beautiful woman with long hair, washing herself or her clothing. Men follow her, and when they are lured far enough from civilisation, they discover she is a creature of evil with the face of a horse or human skull. In parts of Mexico, La Siguanaba is not a woman at all, but a horse-faced man who appears to be a woman. The type of man they target varies—in some legends, they seek out unfaithful men, and in others, men who are in love, drunk, or womanisers. In some places, they also kill children.

La Llorona of Hispano-American folklore is also associated with water, and wears a soaking wet dress. She drowned her children because her husband was having an affair, or because their father was going to take them away to be raised by his wife, or because of some temporary madness. Whatever the reason, consumed with regret, La Llorona drowned herself, too. She became a malevolent phantom, seeking out children, men, or both as her victims. In Arnhem Land, there are oral histories told of the shapeshifting Yawk Yawks, from the Kuninjku/Kunwok language meaning “young woman” and “young woman spirit being”. These watery women lurk in creeks and rivers, or lie in the sun on the riverbank. They are described as having the tails of fish and flowing seaweed for hair— maybe something like a mermaid, but with malicious intent, as they will drag innocent victims down into the water, especially children.

Why so many legends and oral histories about deceptive and treacherous monsters who have no other goal but to haunt a waterway with the intention of luring men or children to their deaths? What deep-seated fear lies behind this? And what about the evidently connected fear of ugly and monstrous people who

disguise themselves as beautiful to ensnare a man and catch him in their net? That this fear of being tricked by a person’s false beauty appears in tandem with such murderous, man-hating monsters is fascinating and ever relevant. We see it exhibited all the time by men who post memes about taking a woman swimming on the first date; men’s rights activists assert that wearing makeup is “lying”. There are “jokes” and dialogue in pop culture obsessed with whether a woman’s breasts are “real”. And of course, there is rampant transphobia: the idea that a trans woman is trying to “trick” men when all she’s trying to do is mind her own business and live her life. These monsters pretend to be beautiful and kill men in one terrible act, lumping the two things together as equally dangerous. Equally criminal.

In light of such monsters and the idea that we must fear and revile them, perhaps it is time to reconsider. Medusa is a source of comfort and inspiration for me. Seeing her not as a monster, not as a victim, but as the survivor and the hero gives her a new face— one that is hideous on purpose, and strong. We must learn to celebrate monsters, be inspired by their stories, and approach them with empathy. What old-fashioned, misogynistic taboos are they representing, and what alternative lessons can we learn? Accepting and embracing difference? Breaking out of traditional gender roles and concepts of gender? Dragging unfaithful men into rivers? We should take pride in our supposed monstrosity.

The following are five more examples of awesome af “monsters” lurking in folklore, myth, and oral histories from around the world who personally resonate with me. There are more, across every culture in the world, one to represent every facet of a person. No matter what you might reclaim as “monstrous” about yourself, there’s an absolutely hideous creature out there who will speak to you. Happy devouring of souls!

Dulklorrkelorrkeng — Arnhem Land Spirits

I was already all about the Dulklorrkelorrkeng and their genderfluid, snake-based lifestyle, and then I read that some say they keep gigantic quolls as pets. No shade to my beloved dog, but he’s no giant quoll! The Dulklorrkelorrkeng have whip

snakes attached to their thumbs, which is badass af, and they also eat poisonous snakes without being poisoned— probably because they are already evil spirits, and you can’t poison evil. Figures like the Dulklorrkelorrkeng hold an important place in Indigenous oral traditions across Australia, imparting valuable knowledge about hazards in the environment. Dulklorrkelorrkengs are invisible, and can only be seen by men who have the gift; however, you can hear them by knocking on the trees that they live in. The Dulklorrkelorrkeng can appear with the characteristics of men or women, whichever it feels like, and the face of a flying fox—which actually sounds more adorable than scary, but they’ve got freakin’ whip snake thumbs, so don’t tell them I said that.

Echidna Ἔχιδνα

— Greek Mythology

Echidna was the MOTHER of all Greek monsters (literally—lots of monsters were her children). She was half beautiful lady, half serpent. Her bottom half might have been a serpent’s tail, or it might have been the front end of a serpent— is there a “vaginas have teeth” message there, and what does it mean? Frankly, I love it. She apparently used it to devour passers-by whole, after she dragged them down into her cave “beneath the secret parts of the holy earth … deep down under a hollow rock far from the deathless gods and mortal men.” That’s a real estate opportunity I am all about. Does Booktopia ship there? I bet even Zeus left this gal alone. Also, did I mention she may have been GIANT?

Penanggal — Malay Folkloric Ghost

I love her. I love that she flies around as a head with her guts hanging out, making everyone they drip on get sick. That is a statement, and as a woman with an excruciating chronic pain condition, I can 9000 per cent get behind just jettisoning everything below my arms. As an ordinary woman in the community, the Penanggal normally has a whole body— but when marauding the countryside in her vampiric form, this absolute Queen only keeps the essentials. Penanggalan are not exactly vampires, but use meditation (and the magic of vinegar) to detach from their bodies and turn into their blood-drinking forms. Variations of the Penanggal exist across South East Asia. For example, in the Philippines there is the Manananggal, who sprouts bat-like wings and in some regions is accompanied by the grisly Tiktik bird,

which makes a sound like “tik-tik-tiktik”—the fainter the call, the closer the Manananggal, which is said to confuse its victims. If it seems like I’m trying to skip over the Penanggal’s diet, it’s because I am. She targets new mothers, drinking the blood from childbirth, and cursing the mother and baby, which is decidedly uncool of her.

Rokurokubi ろくろ首 — Japanese Legend

These Japanese lasses are sometimes depicted as demons, sometimes monsters, and sometimes ghosts. Very often, they’ve not done anything to deserve this shit. They either have a floaty head that leaves their body when they sleep and roams around the countryside going about its business (not even necessarily that evil, sometimes they just be floating), or they have a big long stretchy neck and the head goes on journeys that way. Sometimes, Rokurokubi are aware of what they are, and will deliberately do evil, or mete out punishments to those who deserve them. In other cases, a woman may not even be aware of her condition, and her head goes off flying around while she is sleeping, though she may have strange dreams.

Baba Yaga Ба́ба-Яга́ — Slavic Folklore

This Slavic witch or ogress is a little more ambiguous than the other monstrous ladies on the list. Sometimes she is benevolent; sometimes she offers you wisdom and gifts. Sometimes she eats you. I relate to that kind of unpredictability. We all have our bad days when we just want to eat a Russian prince who comes to our house asking questions. And what a house! Baba Yaga—who is either one old witch or three old witches who are sisters and all have the same name—lives in a cottage on chicken legs. It can get up and move, which is just great for those introverted days when you don’t want to be bothered by the likes of Lithuanian folk heroes looking for advice. And if they do find you, you still have the option of eating them. Why is this maternal figure both benevolent and also an ugly old monster who eats people? What did the society that created this monster think about mothers and their place in the world? Also, where can I obtain my own chicken leg house to avoid Canberra’s rental market?

12

Triformem Bestiam Alisha Nagle

Now on the mountain of the realm known as Khimaira there appeared great jets of light that erupted and spat from the depths of Tartarus, so that the Lycians were afraid and called it the work of a terrible monster. And while innumerable strange and wonderful creatures dwelled in the highlands of Yanartaş, none were so kind-hearted and so pure as the one whom man gave this name of evil.

They went unseen for many ages, appearing as a mass of grey stone embedded into the earth. Complex was their physiognomy, that they had spent years dreaming, for this way the mind could clear and think as one. Deep through dreams and space they remembered Inanna once called them daughter. Inanna had stroked their fur and told them how special they were, though she looked at them in pity. She knew their soul was unfit for the field of battle, that their heavy paws would stop short of bloodlust and cause peril for her militia. Despite the extent of their malice being a tendency to clamp the wings of butterflies in their three jaws, the continued terror of mortals withered Inanna’s gardens where they played; thus, Inanna sent them to the mountainside to dwell in forlorn peace. Yet this creature called Khimaira was of immortal blood—they lived and lived until settlements had swelled not far from the mountain, and that is when this story begins.

At first people thought the apparition

was some wonderful and momentous anomaly of Nature as they spotted them slumbering atop their preferred rock in the summer: a snake coiled across a great goat’s back, lifeless, still. Yet then, seeing the head of the immense front, the muscles ripple in the legs and jaws when they yawned as one abominable trinity—how they were frightened! They saw the tongues of each face emanating vapour, watched them plunge their maned front into the abyss of a blazing pocket in the earth as a babe bathes in warm minerals, and they spread the word that this beast— this invincible Khimaira that burst into flames and felt nothing—must be to blame for the fires on the mountaintop. Few would presume the Khimaira meant no harm save the beasts, who knew the jets were only the deathless ones, the athánatoi, journeying across the cosmos. Mighty Khimaira had no intention of hurting anybody, for they preferred to devour dreams and sunlight—not mortals. And for a short while the people lived undisturbed by this improbable being who roamed the fiery mountaintop.

They were afraid—but mortals are curious. They learnt to brew tea using the heat of the smallest flaming vents beside the waters at the foot of the mountain. The settlements continued to grow. Soon enough, people visited the fires of Yanartaş every day, even the children; they screamed and chattered on their capers around the flames. Their sounds frightened Khimaira—in the evenings, when the smoke and haze of dusk distorted Khimaira’s vision, the young ones seemed like demons, their limbs dancing back and forth as if caught in the breeze.

Khimaira tried to take shelter in the ruined tombs sculpted into the mountain, but they could not dream— incessant voices from below travelled to their ears. And the more Khimaira roamed awake, the more they felt their body grow heavy, and their tongues would sear in the heat of the mountain. It was not all sadness. On winter evenings, when the children fled from the early shadows and the cold, Khimaira would venture down to the riverside, and drink to soothe their burning throats. Man had carved out pastures across the river, and when the hoofed beasts who dwelled there bleated, the Khimaira understood. The goats would inform them of the best grasses in the fields. Khimaira used their tail to pick choice blades and coiled upward to reach their mouth, bleating gratefully in turn—the hoofed ones seemed very glad to soothe Khimaira’s hunger, as they watched on with watery, nervous eyes. But when Khimaira whispered back gratitude with their forked tongue by mistake, the goats began to fear the abomination they saw, with its writhing, poisonous tail.

Khimaira continued to visit the pastures and tried to prove themselves a friend. This caused so much upset with the livestock that some broke loose and bludgeoned themselves against the fence in their desperation to flee, and when at dawn the farmers found their losses, they raged and wielded sharpened beams towards the sky. Khimaira did not understand; but none could deny the hatred and terror in these faces, in their sounds. So, the wretched creature retreated to the fires on the rocks above, and felt their throat

Ibi est mons Chimaera, qui noctibus aestibus ignem exhalat — Etymologiae 14,3,46

burn more fiercely than ever.

Here on the mountain dwelled snakes who basked in the sunlight, with faces solemn like stone. They were not friendly folk, unwilling to approach the great body so as not to be trampled beneath its cloven toes. The larger snakes would even bite Khimaira’s tail as if it were nothing more than a worm to a goshawk.

Khimaira lumbered further, until the grey stone was very bare and there were only the little fires rustling in the crevices for company. At least here there was less noise. But this was a lonely life. They had not dreamed for a very long time. No longer did they even remember who they were, no longer could they think as one. Every decision they made relied on the three—three choices, three urges, to which they felt compelled at once, and often now each was in dissent. Sometimes this was too much, so that they whimpered in agony. They were too much for the land to bear, and it seemed the earth itself cried out in retaliation whenever they awoke. Oh, the torturous, garish light that lay upon their mind as they tried so desperately to extricate themselves from the chaos! One day the largest of their throats let out a great and terrible yawl of a song that vibrated across the grey stone. The air around them distorted; flames sprouted from within. People at the base of the mountain were nearly burnt by the stream of molten heat lolling down the stone. When they saw there was indeed fire bursting from the maw of the mountain beast, they were eaten by fear, and cried to King Iobates for help.

The mighty winged horse Pegasos heard the cries of the Khimaira long before they reached Iobates, and as he was born of snake, having sprung from the neck of Medousa, he knew them to be sad and lonesome. He glided down from Mount Helicon and summoned cascades of water from the heavens. When it rained, the mountain flames lived on, though they would snort and spatter when touched by the soft crystals spinning down from above. They trickled down into Khimaira’s fur and sunk into their flared nostrils with a hiss. The rain was good—it soothed Khimaira’s boiling throat.

When Pegasos swooped across the valley, the people cheered. They loved

him, for his hoofs called divine waters from the aether, and his whinny could change the form of beasts at will, since he possessed the hearts of the Moirai— the goddesses who predestined the fates of all the souls on the earth. But Pegasos did not greet the settlements— he flew until he reached the summit of the mountain, and there nestled into his friend.

Mighty one, why do you cry to me like a sorry wretch?

When Pegasos sang, the air became sweet, and the notes of even his melancholy songs glistened in the air like jewels. Khimaira purred. They smiled at the winged horse, sadly. “Because when we sing, man is afraid…”

The Pegasos said nothing. He shook his gossamer mane, and dashed at full speed past Khimaira so that their fur was tousled in the breeze. Khimaira felt their heart race; they were compelled to follow.

The beasts galloped beside each other on the mountain. Khimaira was so delighted that their romp became lighter than the step of a dragonfly. When their three spirits united, it seemed no monster appeared at all, but instead a great life force was carried on the wind, embedded into all the hidden creatures in the thickets of the mountain, filling them with vivid dreams so that they glowed and thrummed with joy. But as the evening darkened, Pegasos said, “I am sorry—I’ve grown old, and fear that if I remain here longer, my eyes will be scorched. My respite in this land will soon be over, and I’ll need to find my way to the peaks of Ólympos, where one day I am sure we will meet again, and enjoy many days like these.”

This caused the Khimaira great despair. “What will we do without you? We have not a friend left in the world…”

“They say the athánatoi on the mountain are your doing.” When Pegasos spoke, it always seemed as if he talked to himself only, though he must have been listening, for his ears were turned very keenly. “The mortals use the fires to make the river water bubble, and it keeps them living. What they think you give them, has helped them very much.”

“It is not true—the flames have always

been here,” said the Khimaira. “At night we see them fly up into the sky while they laugh and sing lovely songs, like the songs you sing. We envy them.”

The eyes of Pegasos were strange now, and empty like deep, dark pools. When he looked upon the Khimaira, they could not tell which set of eyes he watched; it seemed as if he gazed into all three at once.

Said Pegasos: “You are unhappy here. I give you my freedom, so that you may fly to Ólympos and be rid of this wretched half-life.”

Pegasos dug his foot across the earth and held his muzzle toward the moon, Selene. His whinny caught the attention of the Moirai, and knowing his benevolence, so fashioned the Khimaira wings. They jutted out from Khimaira’s furry torso, gleaming slick and leathery, elastic as a turtle’s neck. Khimaira’s eyes dilated as they watched the wings grow like moths emerging from chrysalides. Their gaze grew enraged. “A wicked, hateful thing! My wing is as ugly as we three,” moaned Khimaira.

“Nay, little one.” Pegasos paused. He had seen a great many beasts, but never had he seen a beast like this. The wings were immense and terrible—perhaps ugly, indeed. And now when Pegasos watched the Khimaira, their lion’s mouth curled back to expose teeth and tongue, he felt his own body stir with rage; he remembered that he was born in murder and in hate, that something in his body sought vengeance against the mortals; and yet all he had ever known was flight. He felt power stir from within his sinewy chest, and, mouth gaping, his own silver tongue rolled out and hissed, though Khimaira did not notice.

Pegasos said, “They are as strong as the wings of Erinyes. They will carry you well. You must let them get a taste for the air—hold them out, as I do; hold them there in the breeze.”

To Khimaira’s amazement, their mind cleared rapidly—they unfurled like an immense bat’s wings, the veins on each ribbed segment visible and teeming with new life. Pegasos nickered gently in approval. “When Selene is bright in the sky, she will light my way to Ólympos, and you will follow me there.”

14

“I do not want to leave this mountain,” the Khimaira agreed as one. And while the Pegasos was absorbed in only dark things, his gift allowed Khimaira to see vividly, like when in the deepest of dreams. Briefly, they dreamed that mortals loved them just as they did the brave horses, that they were rewarded for the life force they imbued, permitted to sing; in doing so, the mortals heard. Khimaira’s great paws lay upon the Pegasos’s shoulder as he turned before the cliff and readied himself for departure. They knew the horse was privy to man’s desires. “Please. When we sing, we are hated, for our tongues tell not the truth—but the mortals love yours. Tell them that we can serve them and share with them wonderful things. Tell them that we are of the same life— that, should they listen…!”

Pegasos snorted and pawed at the earth. “The mortals love me because they think I am tamed. They think that my heart is weak and fickle, and that is why I fly. Khimaira—while I know not why, in you they see my soul plainly—their souls, also. If I speak of you, they will make me a monster, too. Yet I am tasked with bringing order and beauty to the world, and so to be a monster would be to shirk my sole duty. Understand me.”

Khimaira did not understand. But they felt a new light grow inside them, and it shone even as Pegasos disappeared from the horizon. Their mind was clear and controlled when they swept their wings; the water vapour in the clouds calmed them, their fur became glossy and windswept. They were so grateful that they approached the edge of the mountain every night, and sat awake at the cliffside while the stars travelled all around the sky, keeping watch in case Pegasos arrived to fulfil his promise. Slowly, they learnt to find refuge in the clouds by dreaming up above and far from the mortals, where they could sing. Their voice travelled on the breeze, and the people of the mountain listened unknowingly in daydreams; the benign songs whispered to them, so the mortals sang back as they cultivated the fires of Yanartaş that they now treasured, used their heat for ingenious inventions that the Khimaira’s fiery melody carried to them in spirit.

Meanwhile, the Pegasos flew to the west to visit his brother—the creature Bellerophon, who was, too, born from the head of Medousa, yet who stood

upright like a man. In the plain of the River Xanthus in Lycia was Iobates’s kingdom. Bellerophon was a noble guest and hero in the kingdom, and there had heard reports of a goatheaded monster that terrorised the eastern mountain settlements, but to his brother he said nothing of this news.

Bellerophon met Pegasos one evening at the spring of Peirene, and asked him why he was troubled. Pegasos bent his head low above the spring, feeling the full weight of Selene and her chariot of white horses above as they glinted on the water.

“Belle, it is my friend whom they call the Khimaira—they are one like us, and innocent like a foal, though they are feared for their power—I feared them, too. The beast wanted me to calm the mortals, but it is they whom I mistrust the most, and though I speak in many tongues, I claimed the mortals would not understand me, or would believe only the fear in my eyes. And what was most strange was that I felt myself yearn to bring wrath upon the mortals, and desired to lead them astray. But I cannot. So, I thought to bring Khimaira to Ólympos, yet now I find that my eyes grow tired, and I am lost even on the brightest nights… I am so vain, I fear, I fear…”

For a moment, Bellerophon did not speak. It seemed he had heard no more than the first of his brother’s words, and then his mind had drifted elsewhere, while the Pegasos, who was lost to his agony, had eyes only for his square reflection in the shining waters of the spring, for Selene above his shoulder. Bellerophon stared at the bowed neck of his brother, his long, silvery mane flowing in the wind. Then he said slowly, “I’m afraid here we have heard quite a different story. The king Iobates has sent great warriors to slay your beast.”

Pegasos trumpeted in despair. “Oh! You must go at once, Belle, and tell the people they have nothing to fear. It is only we, who see in Khimaira our own cruelty—I know this!”

Bellerophon looked up at Selene in the sky; she grew brighter by the minute. He smiled. “If I leave now even on horseback, I will not arrive in time. You must carry me. Let me on your back, and I will indeed show these people they have nothing to fear.”

And then, the winged Pegasos who had never let a soul guide his path, neither mortal nor god, allowed his brother to take this pride from him. But no sooner had Bellerophon mounted than did he reveal the truth. Foolish Pegasos, to trust in man! Bellerophon had bribed Athena out of her enchanted bridle, which she traded with him so that she might later acquire his quarry. At once Bellerophon stretched the bridle around Pegasos’s jaws, and he could do nothing but follow Belle’s every command, although he snorted and roared, for his forked tongue alone had saved its agency.

Bellerophon flew them to Yanartaş, and so the raging creature saw how he was tricked; there was no cavalry here other than Bellerophon and he, his steed. They approached the peaceful settlement, where the mortals gasped in awe as the winged beast strode among them with wild, blazing eyes; they wondered at Bellerophon’s command. “The Khimaira lives at the top of the mountain,” the villagers told Belle, “but we haven’t seen her for many days now. We think she has gone, although the fires do still glow here at night.”

“I see. King Iobates sent us to relieve you of the devastation this monster has caused.” Bellerophon displayed his patterned seal, and the settlement drowned in his honeyed words, obliging to believe his every demand— Pegasos found that now even he could not speak, as if he too were complicit in Belle’s lies.

Polyeidos the Seer had said to Bellerophon:

Take a lance of lead and poison, And from above you must drive it into her throat

Upon the wing-ed enemy of chaos.

So the villagers took Belle’s lance and dipped it in molten lead. Bellerophon mounted Pegasos and directed him to Mount Khimaira, and like the gales they coursed along toward the tombs at the summit.

That night a great fog rolled down from Mount Khimaira, as if the clouds had descended—to the mortals, it seemed the gods were falling, either to destroy or to cleanse the earth below. From the cliffside the Khimaira lay watching and waiting under Selene’s moonbeams, just as they had done every night, and

15

15

there appeared like a diamond on the horizon the great winged horse. Pegasos saw the faces of his friend, their enormous, leathery wings stretched out wide in a submissive greeting. Upon the Khimaira’s lion-like jowls lay a grin of indeterminable, rapturous villainy, as if the velvety mouth shrieked both with joy and with rage in the silence of the summit. At once the Pegasos screamed: “Do not trust us! Flee, my dear one; I have betrayed you.”

Pegasos’s trumpets could be heard across the whole valley—he groaned and tried to throw Bellerophon, but it was no use, for he could not kick or even shake his head. There on the ashen black mountain Khimaira lingered, and, whining, took flight to follow Pegasos’s trail. Hissing across the great valley, beneath the blaring lustre of Selene, skin like pearls and rippling, then did the Khimaira sing: When we sing, we are hated— See the great Pegasos With the mortals at his back Come to hurt me, to take me I fear! I fear!

Even in torment, it was forever like magic to Khimaira in this air, absorbing the mist of the clouds—below them, all like ants. Only here, it seemed, were they truly free to touch the mortals of Yanarta their unknown hearts. But now, as their heads raised up to view Pegasos, who had soared beyond Selene in the bright sky, they saw the grimace on the man’s face and the beam of poison he carried, and knew for certain that Pegasos had betrayed them.

Khimaira’s rage set flames upon their assailants, but Bellerophon covered his face with his brass shield, and the Khimaira, though hounded and hoaxed, had no real wish to burn

their winged companion. Bellerophon swooped Pegasos above the Khimaira, his body blotting out Selene’s light, and the man drove the lead-tipped lance into the largest of Khimaira’s throats.

Khimaira felt it in their gullet like ice—the flame within them melted the lead, and they could not breathe. They fell through the thick masses of trees below, and because, strangely, they felt no pain, they thought that they must be sleeping, dreaming; but it was not yet so.

Bellerophon pulled at the reins and sent Pegasos galloping into the heavens. “Now, worry not, brother—I can still see the akropolis there, beyond the clouds…!”

Pegasos roared. His roars thundered down through the aether— they travelled all the way to the mountainside below, and there they made the mortals cower in a torrent of hail and lightning. He roared and roared at the Moirai until they brought off his own wings, and he crashed down towards the earth.

“Betrayed!” cried Bellerophon. Aello the harpy heard the dreaded trumpets of Pegasos and swooped down in a flurry of darkness, howling with joy. She plucked Belle into a spinning

by mortal gaze.

Khimaira felt their body rise up from the blackened stone of the mountain. Their paws were limp, and yet something plucked them from above. On their shoulders they felt new, weightless wings attach—wings that were soft and bright, like feathers—they felt the muzzle of their friend brush their mane gently, although they saw nothing.

Once more, the Pegasos sung: Remember the snakes did birth us both, And inside I feel it too, though they do not see; Little one, be not afraid of the darkness, In the bright stars above That guide us to Ólympos, I will wait for you there.

Now the Khimaira did sleep, and the dreams were endless and vivid as in waking life. Their soul remains in the land of Lycia still, invigorating all of Nature’s forms with fervid life, hideous and beautiful. Pegasos awaits them in the stars, riderless, as though he were always free. And unlike the Pegasos, who man watches still on clear nights, little Khimaira was quite forgotten—though the mortals of Yanartaş remained grateful to the spirit

16

Cornucopia: An Interview with Tisha Tejaya

Interview by Lily Harrison

Cornucopia— A tapestry of tropical produce

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of meeting Tisha Tejaya—a vivacious young woman with a personality as exuberant as her vermillion jumpsuit,

and a story about creating “home” in Australia’s dusty red heart. Tisha is a Chinese-Indonesian migrant, woman of colour, artist, lawyer, and emerging writer. In 2020, inspired by her family history, Tisha self-published Parap & Rapid Creek Market, a pocketbook

featuring exquisite botanical illustrations, recipe ideas, folklore, and anecdotes from the Northern Territory’s multicultural market community. Within a week of meeting, a copy of the pocketbook—deftly wrapped in pages of the local newspaper—had

17

landed on the mat at my front door. Captivated by the soft beauty and tender honesty of her illustrations, I sat down with Tisha to learn more about her story, and about the stories she hopes to share through her new creative endeavour, Cornucopia.

When our call connects, Tisha is on Larrakia Country, collecting reference photos of the Yellow Kapok flower— native to the Northern Territory— for an illustration she’ll be drawing later. Taking me on a virtual tour of the swamp area around her, Tisha explains how recent bushfires have left parts of the land black and scorched. As she shows off the yellow blossoms, brightly coloured bladderworts, trigger plants, and swamp lilies going crazy all around her, I’m taken by the symbolism of the scene. Australian natives and introduced herbs and flowers all flourishing together in a cornucopia of beauty against the raw land. A perfect representation of what Tisha aims to illustrate through Cornucopia: the diversity and tenacity of migrants and former refugees living in Australia. The world is not the size of a moringa leaf—“Dunia tak selebar daun kelor”

Tour complete, Tisha settles behind a large rock to muffle the sounds of the wind, and we begin the interview.

Tell me about Cornucopia.

I’m aiming to interview at least 100 migrants and former refugees around the Northern Territory. The big focus is recording how things like food and … art can capture a person’s culture through the generations. I desire to capture the process of migration and adapting to living in Australia.

To me, there are three situations that arise when someone migrates to a different country. The first is when there is a gap—some things don’t transfer. Some memories don’t translate, and some information or cultural practices just stay in the old country. The second is when there is a huge clash, like a conflict of values.

A big one is the clash between kids and parents—when one generation acculturates to the new place way [faster] than the older generation. The third one is the bridging spaces like the markets—and also things like sports or comedy. Things that bring people together, where there’s overlap. That’s what Parap & Rapid Creek Market is about.

With Cornucopia, I want to know more about what happens when there’s conflict or a gap. There’s no handbook on how to come to a new country and still be a good kid while being true to your parents and cultural practices. It’s really hard to form values when you’re stuck between two worlds, and I just hope these stories will help people realise that a lot of things they thought were personal deficiencies are actually structural problems that affect everyone.

So, you’re an ANU-educated lawyer. How did you come to be in the creative space?

My creative journey started while I

was still at ANU. Coming from Darwin, I found the winters really difficult in Canberra. My parents would send me pictures of tropical produce, and I started drawing it because I was really homesick and wanted to have that little piece of Darwin here with me. I drew probably about nine tiny card-sized pictures of tropical produce over the course of my law degree. But when I came back to Darwin and was [admitted] as a lawyer I kind of just shelved that and … didn’t do anything with [drawing] until 2020 … when I really wanted to know more about my cultural roots and started going to the markets regularly.

Was there a catalyst for your renewed interest?

I think there were two—the first was that I realised I was the same age my parents were when they came to Australia. [In many ways,] our circumstances are really similar, [but] I can’t imagine now moving to a different country that speaks a different language with a completely different set of people. I mean, I wouldn’t even know if they had the same food that I eat here. How did my parents make that journey? I think it’s incredible that migrants and former refugees do it.

The other catalyst was that I was working as a judge’s associate and I was feeling burnt out about being in law. It’s important that [criminal] cases are heard and dealt with, but I just felt like every day, we were bombarded with the worst stories possible. I thought, “I don’t like how the only time I’m seeing humanity is at its worst when at the same time, I’ve got people around me who are talking about such resilience and generosity and bravery.” I decided to learn more about people’s journeys and realise how strong … our community is. The bad stories will always be preserved in court records … I wish we did the same with good stories, but they’re what usually slips away.

What do you think sharing these

18

Moringa

Leaf

stories means for the people they belong to?

I think it is always important that our stories are recorded, and it would be good for them to be reflected in mainstream media. But I think the impact is even more personal and raw, because I’m inviting a lot of migrants and former refugees to reflect on a past they wouldn’t normally reflect on. I think a pattern with migrants is that we tend to just look at the future and we don’t like to look at the past. My favourite part of interviewing people is when I ask, “Can you imagine talking to yourself when you first came to Australia and things were so uncertain and you didn’t know the language? Look at you now, you’ve made it. How do you feel?” I think that journey of looking back and seeing how far we’ve come is the biggest thing.

A flow-on effect … is that it brings families closer together. When I’m interviewing migrants, their kids will usually be the ones helping me interpret their parents’ stories—and they’ll hear stories they’ve never heard before. I think [hearing them] helps explain so much because sometimes, when you’re sitting between two cultures, what your parents do makes no sense, it seems arbitrary and cruel—but when you hear why your parents are the way they are … it bridges that generational gap of what might otherwise be distrust or misunderstanding by raising awareness that we’re all just trying our best. So much can be lost in definitions and different languages and different cultural practices, but in the end, this is what we are.

Why the Northern Territory? What makes the stories you’ll find there special?

A big attraction of the Northern Territory is that it’s really properly multicultural. [Many] different cultural groups mingle together with food, sport, and art, and you get a lot of friendships across different multicultural groups rather than enclaves. [Like the] growers …

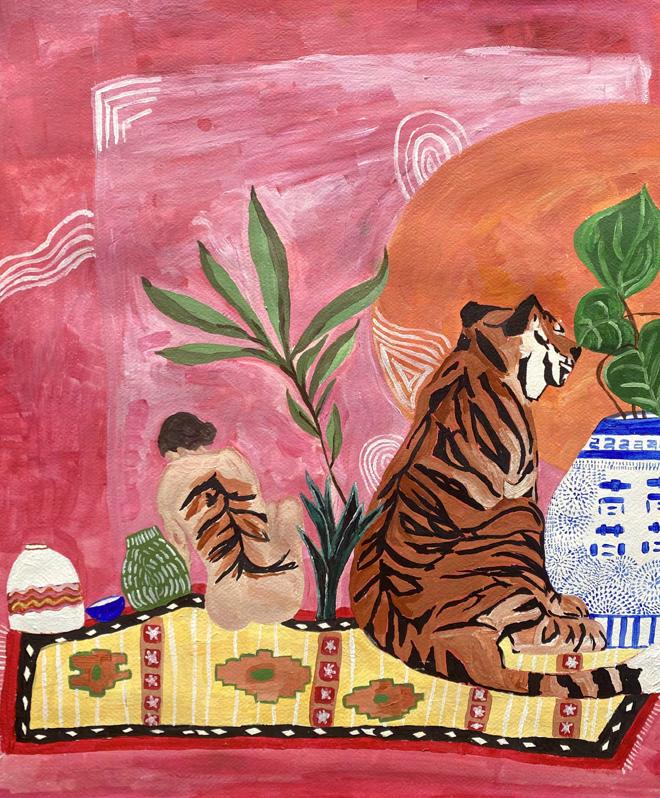

Lilies (Crinum uniflorum) on a Tiger

who took care of my family when we first moved here—my story is threaded through here, as well.

Another is that there’s so much outback in the territory and rugged natural life. [There are] so many deadly and poisonous creatures here—it’s a challenging environment, and I really enjoy talking to people who have professions connected to the land. Whether it be fishing, mud crabbing, growing fruit or vegetables or crops, this is a hard cowboy land to be living on, and it’s fascinating how creative [people are], and how much gumption people have here. For me, the NT is the central heart of Australia.

Tell me about food. What does food represent in the migrant experience?

Food represents an ephemeral memory vessel. When you ask people for their memory of a specific thing, I don’t think it will ever be evoked as viscerally as when food is the thing to trigger it. When a person cooks their family recipe or eats [food], they remember things so vividly and are able to share them. For me, coming from a multicultural family, and because of language [or

value] barriers, so many things don’t get passed on. That’s where food steps in to remind people … I think it’s a really powerful way to bridge those gaps and to share memories and traditions and values that aren’t easily communicated across languages. Food is not controversial. It’s gentle—it’s a loving space … of understanding and of nourishment, because you’re trying to keep each other healthy. It’s a universal form of affection.

Can you tell me more about what the market represents for you in terms of identity and belonging?

When I wanted to learn more about my history and my family’s history, I found it really hard to talk to my parents—it wouldn’t feel like we were speaking the same language, even though we were both speaking English or Bahasa. It was hard for my parents to open up about past memories because a lot of what happened was really traumatic, and the memories of coming here were really just in the past. Even though we’re all physically fine, it was a very stressful time leaving my grandparents behind, and I guess there’s a lot of guilt associated with that, too. The markets

19

Swamp

were such a wonderful place to be because when I talked to stall holders, often bringing my parents or aunty with me, people would start remembering the things they didn’t want to remember or answer if I had just bluntly asked them. People wouldn’t know how to answer questions like: “Why did you come to Australia?”, “What was the war like back home?”, or “What was the hardest part about coming to Australia?”

But coming through the markets and saying, “Oh, we used to cook this because back in the day it was a really cheap thing to cook”, would make the memories bloom back, and I heard so many stories that I wouldn’t have even dreamed I’d access.

I think it really helped to coalesce my identity as a migrant and as an Australian. When people at the markets started opening up about their journey coming to Australia, their struggles, and how proud they are—even though there’s a reason we left the old country and came here, we’re still proud of our culture back at home. I learnt that you can be proud of being Australian and also have a really rich cultural heritage—the two aren’t mutually exclusive. In fact, they enhance each other. The markets are a huge part of my life now—they mean a lot to my identity because they’re the bridging space that allowed me to come back

Drumstick

toward my cultural roots as a migrant, as a Teochew-Chinese woman, and as an Indonesian woman.

What does it mean for you to now feel comfortable in your identity and embracing your culture?

It feels pretty incredible. I think that’s a product not only of the changing environment where multiculturalism and diversity are celebrated, but also growing up a little bit and getting more comfortable with who I am.

For a lot of my life in Australia, I didn’t know much about my cultural identity—and to be

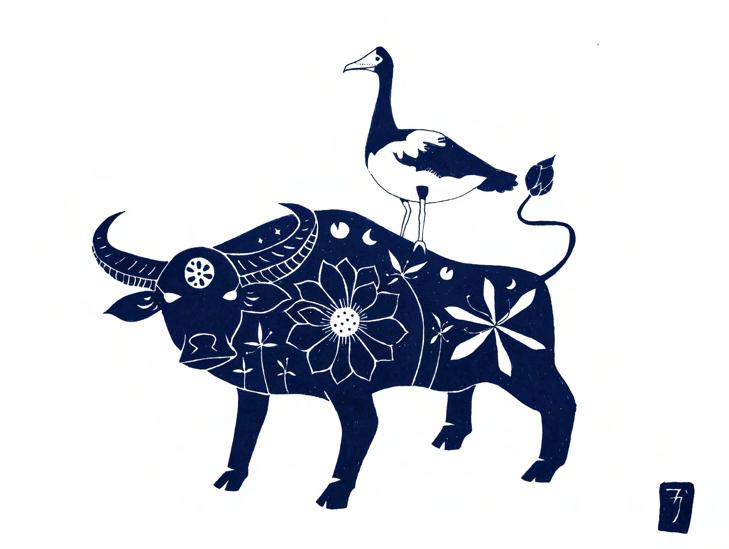

Swamp Lilies on an Ox

20

Moringa

honest, I didn’t really want to. When I was a kid, I felt like I had to wear very different masks depending on where I was—at school, I wanted to be as Aussie as possible and to eat pies; I didn’t want to eat curry, or have my parents’ chilli tolerance teased, or be asked if I was eating cat or dog. At home, I tried to be as obedient and quiet as possible. It was so difficult when those two worlds would interact … my identity would go haywire and just crack. Now that I’m grown, and more confident in who I am and in my rich cultural background and identity, I’m in a space where I really love it when I talk about my family’s food … I feel like I can relax and be really happy for and proud of my community, and that I’m a part of it. I guess when you

feel like you can breathe, you realise how tightly you’ve been holding your breath.

Is there a word or phrase that encapsulates Cornucopia?

“人不打汝 , 汝 打人” is a Teochew phrase. In pinyin, it is roughly pronounced: “nang boi pak leu, leu pak nang” and directly translated into English, it means: “People don’t hit you, you hit people”. This phrase embodies the Teochew pride and selfawareness that we are quarrelsome people. It’s significant to me because it captures the fighting spirit that my family and culture has carried through the generations, despite being far from our ancestral village in South

East China. Though I’ve known of the phrase since I was a kid, I’ve only realised its deeper personal meaning in the past few years as I’ve started having these conversations with my family about our identity and cultural background. The phrase has become sort of an inside joke for my mum and dad, and I value the way I’m now in on it. I think “人不打汝 , 汝 打人” also encapsulates my vision for Cornucopia because it acknowledges the tension that can exist between people and cultures. I find it deeply comforting … to be talking to more people about the conflict of being in two cultures and whether it is possible to live harmoniously in both.

21

'Lily', inspired by the Blue Water Lily (Nymphaea violacea) that is native to Northern Australia

Pliny the Elder Attempts to Describe the Poet for His Natural Histories Bastian deBont

Precocity in youth is a sign of an early death the poet, was attacked with fever every year His head almost severed from his body, he lay the whole of the day upon the seashore A truly graceful device. How has the animal acquired this knowledge? And where has it seen him before, of whom it stands in such dread? By the variety of appearances which it assumes, it puzzles the observers. Its aspect was hideous

Possesses in itself both sexes, being a male during one year, and a female the next These are mutually bound together, and they are often to be found clasped in each other's talons.

To confess the truth

Though I am not quite sure that its existence is not all a fable But, for the present, we are treating of the operations of nature, and not of miracles And so much the more disgraceful is our ignorance, we ought not to be ungrateful to this one part of nature I consider the ignorance of her nature as one of the evil effects of an ungrateful mind.

In keeping with this edition’s theme of Chimera, I’ve constructed a Frankenstein’s monster out of lines from Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, forming a self-portrait out of his descriptions of other animals, objects, people, and phenomena. Natural History was an attempt to describe and categorise everything known to mankind at that moment in time, but is notable today for the many false assertions and conclusions within, and is arguably more well known for all it excludes as well as includes. If we are lucky, then there will always be more undiscovered, strange things in this world

22

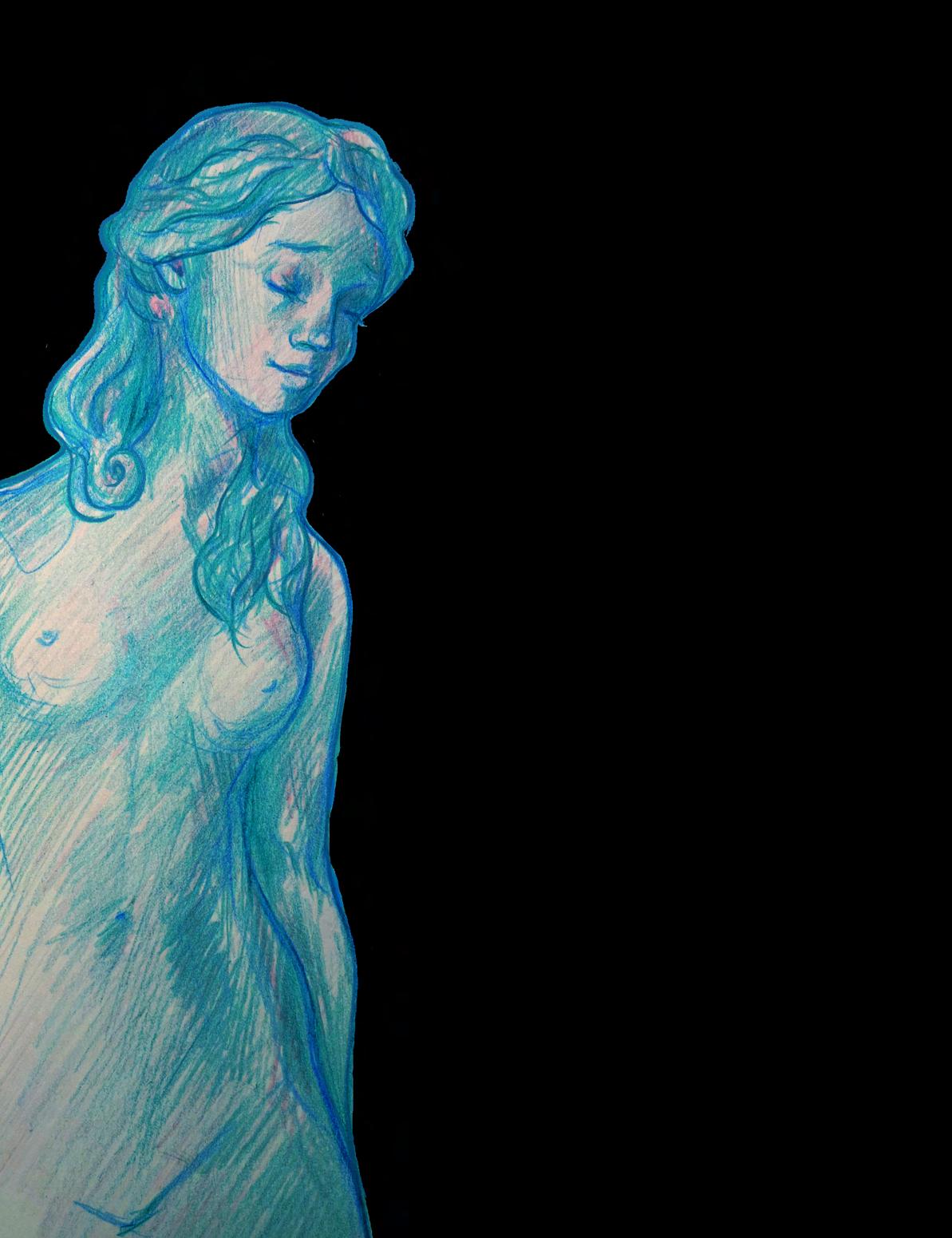

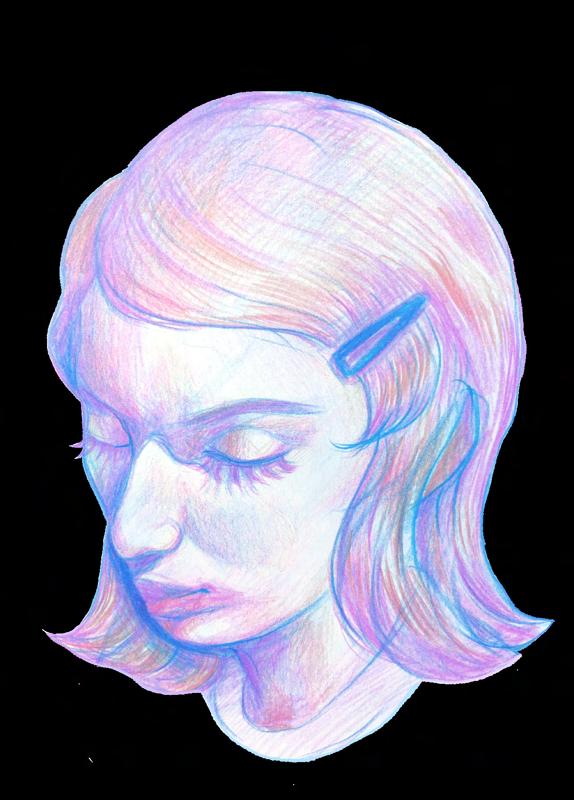

Self-Portraits

Jamie Cardillo

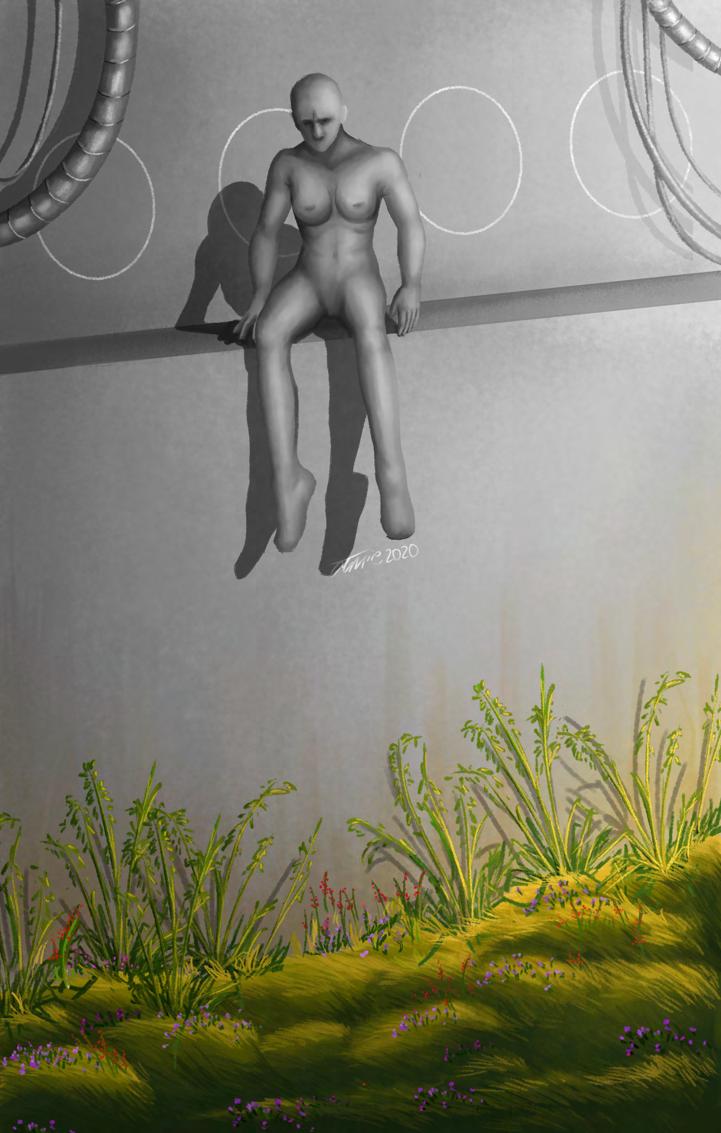

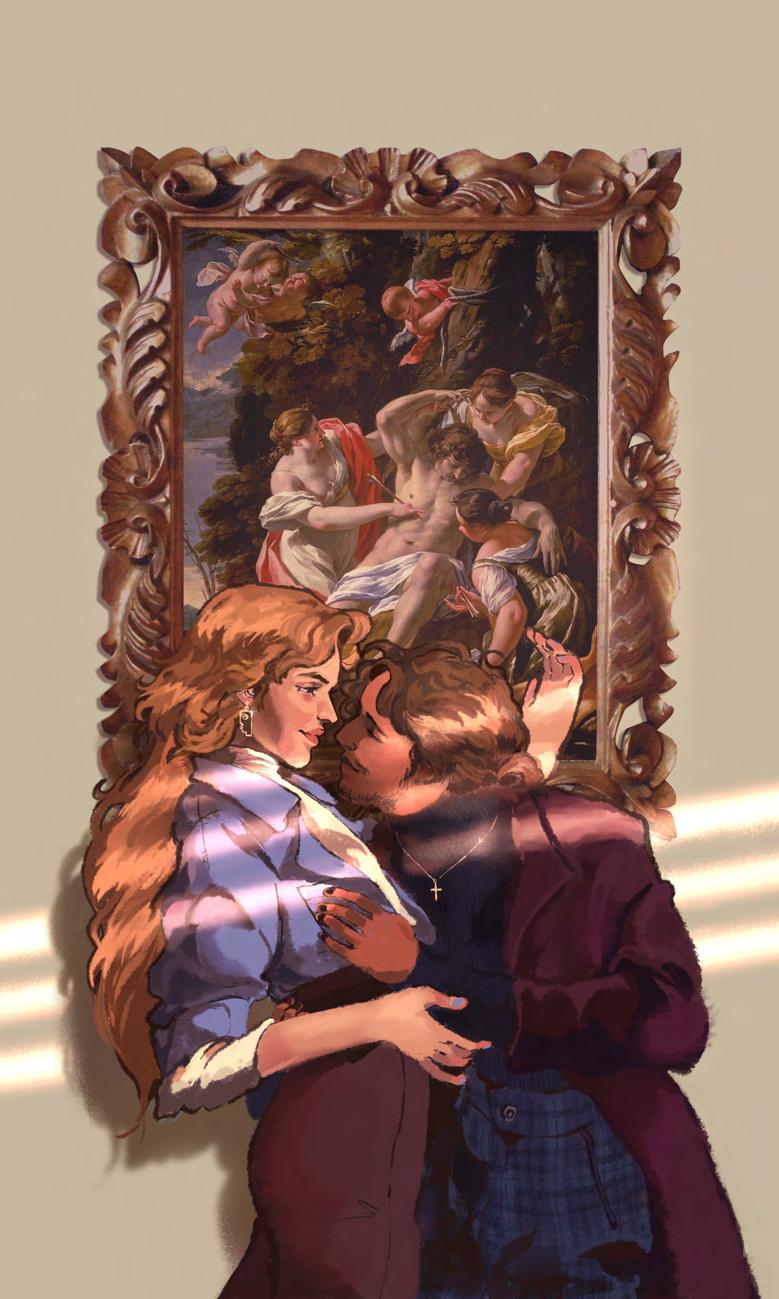

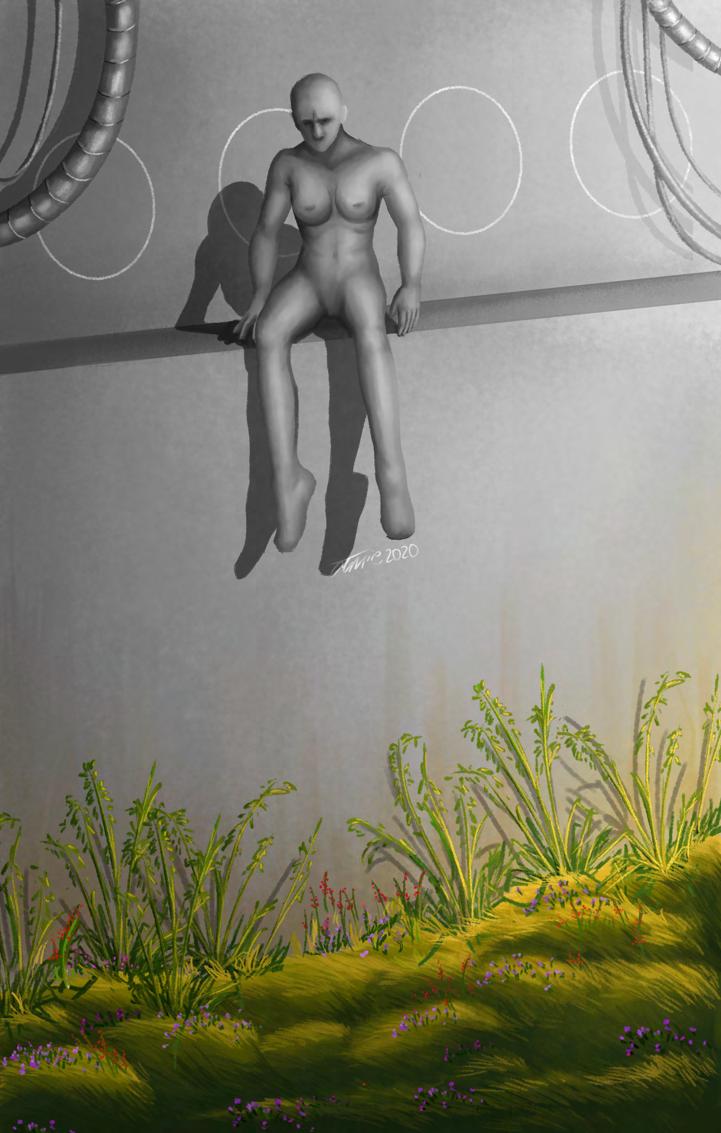

A self-portrait is defined as “a portrait that an artist produces of themselves.” At first glance, the pieces in this collection may not resemble the typical idea of the self-portrait—however, although surreal and dreamlike, each shape and concept within these pieces reflect the person behind the iPad and Apple Pencil who created them. In ‘The Leap’ (2020), I've captured many aspects of my queer identity; sexless, genderless, and undefined, the figure on the ledge fixes their eyes on the warmth and softness of a field that has flourished long before they came into existence, revelling in the growth of generations before them and waiting to take the leap into further self-discovery.

‘Shrimp’ (2021) is fanart of my favourite game series and captures how integral my interests are to my identity. The Rusty Lake series has been an important part of my creative journey over the years. Fanart has kept me drawing during long periods of intense art block, and Rusty Lake played a significant role in the development of my current art style. The dark themes and surreal imagery of Rusty Lake reflect the concepts I love to explore, both in my original pieces and fanart.

24

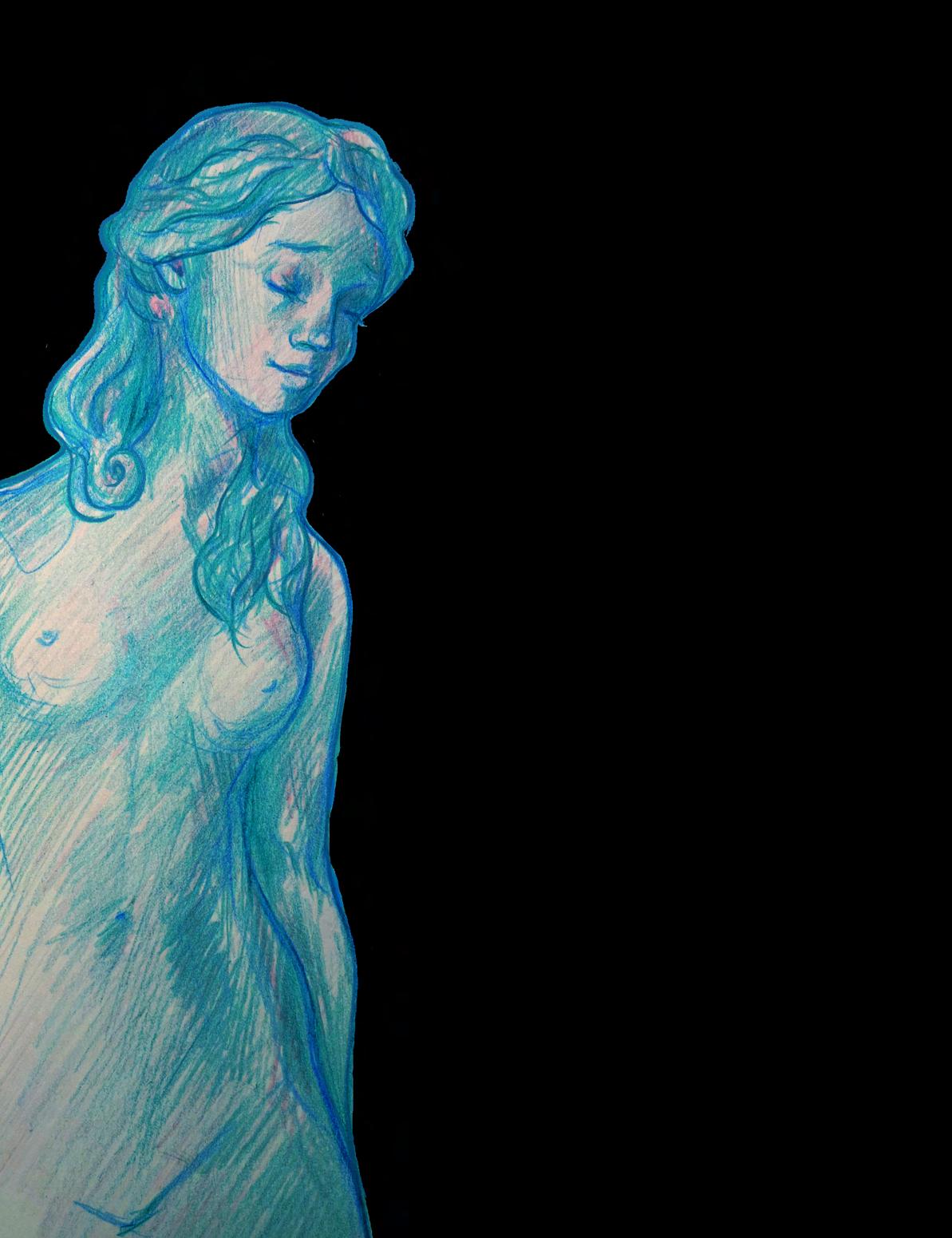

Finally, ‘Chimera’ (2022) is a piece I created specifically for this edition of Bossy. Much like how the three heads of the Chimera work together to form the whole, I find within myself three main aspects of my identity—body, mind, and energy—that form a definite yet incongruous mass, which in turn forms me in my entirety. I am surreal, I am dreamlike, I am so simple yet infinitely complex. While these three pieces may defy the literal meaning of “self-portrait”, within them I have produced myself.

Jamie Cardillo (they/them) is a second-year ANU student studying a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in English. A self-taught artist since 2016, they use digital media to create darkly surreal designs that draw from their queer identity, involvement in activism, and interest in classical mythology. Although originally based in traditional colour artwork, Jamie now works in greyscale, often incorporating only a single point of colour or no colour at all in their art. They like to include an array of intricate visual details in their pieces so that viewers can experience their art many times and always find something interesting.

25

Behind the Blog: An Interview with Samia Ejaz Interview by Christie Winn

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Samia Ejaz is the creator of the 50immigrants Project, an Instagram blog sharing the stories of immigrants living in Australia. Inspired by her own experiences, Samia’s aim is to create not only a platform where she may share the stories of immigrants, but a broader community that shares the bond of common experience. At the time of this interview, 50immigrants had 25 immigrant stories posted, having grown well beyond the goals Samia initially set for the blog.

First, can you tell me a little bit about yourself and your own story?

Before immigrating to Australia, I lived in Dubai as an expatriate. My parents are both of Pakistani origin, and they raised me with South Asian cultural norms that were also influenced by my immediate Middle Eastern society. My family’s decision to move to Australia was largely motivated by the education and career opportunities available here.

What led you to create the 50immigrants project?

Upon interacting with other immigrants, I realised most of us had stories we wanted to share with our broader communities. My vision for 50immigrants was just that—encapsulating people’s stories using art as a form of self-expression.

Tell me a little bit about the creative process behind the project (i.e., finding people who are willing to share their stories).

It has been quite challenging to reach out beyond my circle of immigrant friends, but I am happy to have found some success in sourcing stories from strangers across Australia. A lot of research and thinking has gone into appropriately marketing the blog and maintaining engagement online. While people love sharing their anecdotes, it is often hard for them to condense their stories within the word limit appropriate for an Instagram blog. For this reason, I’ve also spent considerable time creating prompt sheets and engaging through the Stories feature on Instagram in an effort to inspire submissions to the blog.

You note that it is challenging to reach out beyond your circle. Do you think there is a reason for this? Are people ever hesitant?

Reaching out to people poses many challenges, particularly regarding how and when I pitch the blog. A lot of work goes into convincing people that what you are doing is worth their time, and even more effort goes into convincing them that their story is worth sharing! Interestingly, quite a few of the stories already posted feature very open and honest details about the writers’ experiences; since a lot of these people chose to stay anonymous, I think they were less hesitant to share their stories.

In many of your accompanying illustrations, your subjects are faceless. Is this intentional, related to the desire for anonymity? Is there a message being conveyed?

I think minimalist art styles have an appeal to them, and the decision to opt for faceless portraits has also helped me create a safer platform for sharing stories. There is comfort in anonymity, which has thus far enabled people to be more open about the stories they share. While each portrait is faceless, I put a lot of consideration into personalising them.

I definitely see this personalisation working tonally. I love how when I see the art, I don’t notice that there is no face, because I feel a sense of

26

Art by

Ejaz.

Samia

learned a lot from experience, yet significant trialling still goes into making sure a drawing looks personalised enough. It is challenging, but I love seeing the picture come together, and this is what keeps driving me.

You mentioned that having the subjects faceless creates a safer platform and that anonymity provides a certain level of comfort. Do you think this is because of the negativity we know can be associated with social media? Or is it purely due to nerves from sharing a personal story with the world?

I think it is a bit of both. Not only is it nerve-wracking to get personal and candid on the Internet (for some people, at least), but there is a lot of stigma associated with certain themes that come up in immigrant lives. Personal image becomes a huge factor when people begin to open up, and to me, this is a natural response—hence, I provide the option to stay anonymous.

Throughout your blog, there is a recurring theme of the challenges involved in being raised with varying cultural norms. How do you think your project creates a sense of community and/or spaces of belonging amongst immigrants?

Through the collection of stories on the blog, I’ve realised that we’ve been able

to develop a sense of shared experience. People resonate with the struggles and successes of others from similar backgrounds, and this does wonders for emphasising the intricate connections within the immigrant community.

Bossy’s print theme this year, Chimera, is about proclaiming ourselves as we are—making our true identities and stories known and accepting the facets of our own being that have been concealed to keep others comfortable—do you think 50immigrants embraces this goal?

Can you see any similarities in your project, or even in yourself?

I think Chimera is a brilliant reflection of 50immigrants and my personal values that are at the heart of the blog. Most immigrants spend considerable time trying to adjust to their multifaceted identities, often plagued by conflicting cultural norms and life philosophies. In beginning to share the vulnerable parts of ourselves, we can encourage others to do the same—to begin to acknowledge and perhaps even accept ourselves for all that we truly are.

My biggest takeaway from running the blog has been the striking diversity in experiences. While most of the stories shared thus far are united in their common search for “belonging far from home”, it is astounding how every contributor’s journey is shaped by unique experiences, perspectives, and learnings. Upon close inspection, no two stories have been 100 per cent similar; rather, parts of an individual’s experiences may be shared with others, creating a beautifully complex fabric of interconnectedness.

It is interesting to realise that people react very differently even during circumstances that may appear similar on the surface. I feel that it is this very thing that imbues a human quality to the contributions, and I can’t help but think of this collection as a capsule of sorts. That

thought in itself is a strong motivator for keeping the blog running.

These realisations have been reassuring. While I have definitely found comfort in the knowledge of shared experiences, I believe the blog has done an even better job at strengthening my sense of empathy and resilience. Life’s events often challenge us, and sometimes we can get a little wrapped up in them; to learn that others have mustered the courage to get through their share of struggle is both empowering and enlightening. I personally feel that every shared story is a reminder to embrace my inherent mix of cultural ideology— that it really is okay to find your own version of harmony within this mix, and more importantly, it is okay to do so at your own pace.

Finally, is there anything else you wish to include or share?

I hope we can all create environments that not only encourage self-expression, but also embrace it. If you would like to contribute to my small attempt at doing this, feel free to message me at @50immigrants on Instagram or via email at samia.ejaz2000@gmail.com

27

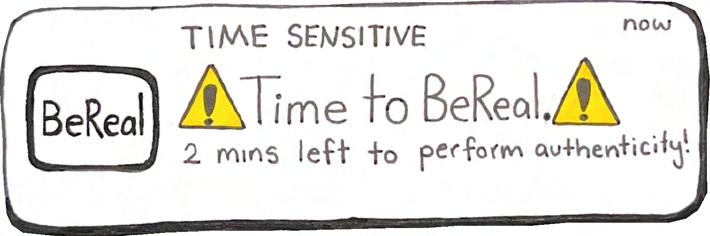

A Reading Renaissance? Reviewing the Influence of BookTok Harriet Sherlock

If you are anything like me, you spent your childhood consuming all the books you could get your hands on: the Rainbow Magic series (I was devastated when the fairy with my name was the Hamster Fairy) led to an intense dystopian and fantasy obsession (cue Chosen One tropes and questionable romantic age gaps), with plenty of Archive of Our Own (an open-source FanFiction site) in between. You called yourself a bookworm, until one day you realised that despite your bursting bookcase, you hadn’t actually read anything other than international political theory in years. While my collection of books has never stopped growing, I have only recently gotten back into consistently reading fiction—and honestly, I have TikTok to thank for that. Despite my initial resistance, I have been an avid TikTok user since the lockdown of 2020 (please don’t ask to see my screen time), and a big part of my For You page has by now been taken over by BookTok. This “side” of TikTok is full of book hauls,

commentaries, micro-reviews, book memes, and people showing off their beautifully curated bookshelves.

I’m not the only one whose love for reading has been newly revived by the app. In recent months, BookTok has drastically driven up the sale of print books and sent many older titles to the top of the bestseller list: you don’t have to look further than your local Dymocks to find specially curated #BookTok displays. Reading culture and communities on social media are not new—BookTube, a space on YouTube similarly dedicated to reviewing and discussing books, has existed for years— so why has BookTok taken off in a way that other corners of the Internet never did? TikTok’s algorithm, I suspect, plays no small part in its success. The curated environment of TikTok users’ feeds, based on their interests and content consumption, means that people who are curious about reading do not have to exert much effort to find relevant content; it is simply fed to them in a never-ending stream. The bitesized nature of TikTok content often means that creators will choose to focus on specific themes or aspects of a book, which further bolsters the algorithm’s ability to pinpoint readers’ tastes within a genre. Not only can you find broader Romance recommendations, but books containing enemies to lovers or the “one bed” trope. Other social media platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, Facebook—and even Tumblr—require users to manually search for and follow

creators, and typically provide much longer content to consume. Being able to exist in select subcultures of likeminded people, without the need to search for them, allows users to easily discover new authors and books that are tailored to their most specific interests, and enter into conversations that may otherwise feel unavailable to them. Similar to swiping left and right through your Tinder feed, every slide of the finger leads to another sweet, sweet dopamine hit from each new video. This intense yet effortless immersion invites people to take up the identity of the insatiable reader they may have once been in their youth, and is a large part of the platform’s appeal.

Many of the books that are popular on BookTok fall into the category of Young and New Adult. Young and New Adult books—in particular, those in the Romance genre—have long been stigmatised as “lowbrow”, immature fiction, or even disparaged as “chick lit”. The condemnation and belittlement of young women’s interests as superficial is not new nor exclusive to reading; yet today, it is these young women who are skyrocketing book sales and altering the publishing industry as we know it. Part of my reading hiatus may have had something to do with my internalisation of these associations: in favouring “intellectual” types of books, I wasn’t allowing myself to just enjoy what I was reading. Many other TikTok users have similarly admitted to feeling as though limiting their reading to the “classics” is considered an intellectual imperative; if not achieved, it indicates a lack of care, attention, or thought. Critically engaging with the content I consume and the world around me is something that I want

28

to do every day—but maybe this ability isn’t limited to the classics. When you read a romance novel, you are watching someone intimately discover just how important and necessary another person or people are to them—it might appear silly, but in times when I despair at the ways humans interact with one another, it can actually feel quite healing.