BOSTONLYRICOPERA

April 2023

Dear Opera Curious and Opera-Lovers alike, Boston Lyric Opera is pleased to welcome you to the Cutler Majestic Theatre as we present Rhiannon Giddens’ and Michael Abels’ new opera Omar. Through the shifting darkness of memories and imagination, Omar invites us to bear witness to one man’s journey in remaining true to himself, his people, and his faith – against all odds. Omar sheds light on a long-disregarded true story, lifting it into the light with a richly orchestrated score combining sounds and melodies from Americana, Arabic, and West African folk traditions to create a radiant narrative of strength, resilience, and conviction.

Opera is an art form that can contain big emotions. The experience of seeing and hearing live, professional opera is one-of-a-kind and we encourage you to explore the world of the opera outside the theater as well. We are proud to offer this Guide to support your engagement with this opera. Please note that this Guide describes plot details. Our intent is to provide support in historical as well as contemporary context, along with tools to thoughtfully reflect on the opera before or after you attend.

Boston Lyric Opera inspires, entertains, and connects communities through compelling performances, programs, and gatherings. Our vision is to create operatic moments that enrich everyday life. As we continue to develop additional Guides, we want your feedback. Please tell us about how you use this guide and how it can best serve your educational needs by emailing education@blo.org.

If you’re interested in engaging with us further and learning about additional opera education opportunities with Boston Lyric Opera, please visit blo.org/education to discover our programs and initiatives.

See you at the opera!

Sincerely,

Rebecca Ann S. Kirk, M.Ed. Director of Community and Learning

OMAR

A GUIDE TO THE OPERA SYNOPSIS

ACT I

Futa Toro, Senegal, 1807. Omar Ibn Said reads the Qur’an. In the background, the villagers and Omar’s mother pray to Allah, asking for guidance and assistance. Slavers have been pillaging the region, and Omar’s brother, convinced that an agreement will secure peace, negotiates with them. While Omar prefers to leave his fate in Allah’s hands, his brother is determined to control his destiny, and he leaves to talk to the slavers. Suddenly, the village is raided, and Omar’s brother discovers that he has been deceived. Slavers overrun the village and begin taking villagers prisoner. In the chaos, Omar is separated from his family, and his mother is murdered. Omar is dragged away to a slave ship.

The Middle Passage. Omar is shackled with imprisoned men in the hold of a cargo ship. They do not speak the same language and struggle to introduce themselves. Unsanitary and inhumane conditions in the cargo hold have caused disease and death. Meanwhile, the two white slavers watch over the prisoners, concerned about the impact of the high death rate on their future profits.

The Slave Market, Charleston, South Carolina. Julie, an enslaved woman, is dragged into the market for sale by a white kidnapper. She plans to escape him at the market and return to the Owens’ plantation in Fayetteville. At the market, she encounters Omar, but he cannot understand her English. Undeterred, she tells Omar that if he were to escape, he should find Master James Owen in Fayetteville. The auction begins, and a family is separated. When Omar goes up for auction, he notices that Julie has gotten free of her bonds. To create a diversion, Omar falls to his knees and prays loudly, giving Julie a chance to escape. However, doing so makes Omar less desirable, and he is sold to Johnson, a plantation owner.

Johnson’s plantation. Enslaved workers chatter about the newcomer, Omar – he doesn’t seem to be fit for working on the plantation. Johnson demonstrates his vicious temperament, striking a worker. He yells at Omar in an attempt to bully him into submission, but from Omar’s perspective, the words are garbled; Omar cannot understand him. Finally, Johnson sends Omar to pick cotton in the fields. Omar hesitantly responds.

Five months later. The spirit of Omar’s mother encourages Omar to pray to Allah and reminds him of Julie’s recommendation. Exhausted and distraught by his terrible life on the Johnson plantation, Omar flees in search of Fayetteville.

ACT II

Fayetteville County Jail. Omar has been captured and brought to the county jail. The chorus swirls with questions about Omar: Who owns him? Who let him get away? Omar prays and writes on the jail’s walls, capturing the attention of the daughter of plantation owner James Owen. Calling his writing “magic,” she encourages Owen to purchase Omar. Owen is fascinated by Omar’s religious piety and believes Omar can be converted to Christianity.

Owen’s plantation. Katie Ellen, one of the enslaved workers on the plantation, is surprised that Julie came back. Owen introduces Omar to the other enslaved people, and they welcome him. Seeing that all is well, Owen takes his leave. Omar thanks Allah for guiding him to Fayetteville, and he is reunited with Julie. She reveals that her father had worn a cap like his and had prayed to the same god. But her father has been sold down the river, and she holds on “to memories, to histories, to feelings.”

Owen’s study. Omar is summoned and accompanied by Katie Ellen and Julie to Owen’s study. Owen and Taylor, a visitor from the North, discuss the prospect of converting Omar to Christianity. Owen gives Omar a Bible written in Arabic, and he and Taylor begin to coach Omar on writing the Lord’s Prayer. Instead, Omar defiantly expresses his desire to go home in Arabic.

Later that day, Owen’s plantation. Omar sits alone under a tree reading the Arabic Bible. He reflects on his life, thinks of his mother, and asks for forgiveness in Arabic. In the final scene, Julie is amazed that Omar can read and write. She encourages him to write a book to tell his story, and her suggestion is seconded by Omar’s mother. In writing, Omar gives praise for the beauty of the world: Allah flows through his pen.

CHARACTERS

North Carolina

KATIE ELLEN , mezzo

An enslaved woman on Owen’s plantation.

South Carolina

OWEN , tenor

An enslaved woman on Owen’s plantation.

ELIZA , mezzo soprano

The young daughter of James Owen, a

TAYLOR , tenor

A friend of Owen visiting from the North.

AUCTIONEER , tenor

The man who presides over the slave market in Charleston.

JOHNSON , baritone

A plantation owner in South Carolina.

ABE , baritone

A man who is separated from his beloved family at the slave market in Charleston.

JULIE , soprano

An enslaved woman on Owen’s plantation.

Futa Toro, Senegal

OMAR , tenor

Omar Ibn Said, a man from Futa Toro, Senegal, who, in 1807, is kidnapped,brought to Charleston, South Carolina, and sold into slavery.

FATIMA , mezzo-soprano

The mother of Omar, who is murdered by slavers in Futa Toro but remains a guiding presence in Omar’s life even after her death.

ABDUL , baritone

Omar’s brother, who attempts to negotiate with the slavers in the region, but is deceived.

THE COMPOSERS

OMAR WAS WRITTEN BY TWO COMPOSERS:

Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels. Giddens also wrote the libretto, inspired by Dr. Ala Alryyes’ translation of Omar Ibn Said’s autobiography, titled A Muslim American Slave: The Life of Omar Ibn Said. The idea for Omar originated from an intellectual fascination: when the then-director of the Spoleto Festival Nigel Redden first learned about Omar’s work, he was captivated by the power of his story. In 2017, Redden and producer Nicole Taney first approached Giddens, a self-described “performing historian,” to write an opera about Omar. After writing the libretto, Giddens then brought on Abels to the project to flesh out the musical world.

Rhiannon Giddens.

Photo by Schorle Creative Commons.

Michael Ables.

Photo by Eric Schwabel. Creative Commons.

Rhiannon Giddens.

Photo by Schorle Creative Commons.

Michael Ables.

Photo by Eric Schwabel. Creative Commons.

Rhiannon Giddens is a musician and composer best known for her stylistic musical combinations of folk, bluegrass, and jazz. As an accomplished vocalist and instrumentalist —she plays the fiddle (violin), banjo, and viola—she can be found performing as a solo artist, in duets with multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi, and with the old-time string and banjo bands she founded, The Carolina Chocolate Drops and Our Native Daughters. Originally from North Carolina, Giddens attended Oberlin Conservatory to train as a singer and musician

in opera and Western art music, and since her graduation, she has built a storied career spanning continents, musical genres, and ensembles. The many awards she has received include two Grammy awards and eight additional nominations, the MacArthur “Genius Grant,” the inaugural Legacy of Americana Award from Nashville’s National Museum of African American History, and she was featured on Ken Burns’ Country Music series on PBS. In 2020, Giddens was named the artistic director of the Grammy-winning Silkroad, originally founded by Yo-Yo Ma. In addition to the success of her opera Omar, she recently published her first book, Build a House (2022), and the ballet she wrote the music for, Lucy Negro Redux, began a national tour.

Michael Abels is a composer best known for his scores for Jordan Peele’s films such as Get Out (2017) and Us (2019). His work is genredefying, drawing on influences from hip-hop, jazz, gospel, and classical music. The score for Us has been short-listed for the Oscar, and he has been nominated and won a

dizzying list of best original score awards from various film critics associations. In addition to film scores, Abels has written a number of chamber and orchestral works for prominent ensembles in Chicago, Cleveland, Atlanta, Houston, Baltimore, Dallas, Detroit, and Nashville. Born in Phoenix, Arizona, he grew up in rural South Dakota and later attended the University of Southern California. Abels is also a conductor and the co-founder of the Composers Diversity Collective, an advocacy group to increase visibility of composers of color in film, game and streaming media.

OMAR IBN SAID: THE MAN AND HIS STORY

The opera Omar was inspired by an autobiography written by Omar Ibn Said.

Omar was an enslaved man who lived in Futa Toro in what is now Senegal. Like many “first-generation” enslaved peoples who were trafficked to the United States, Omar was literate prior to his captivity. However, literacy was often forbidden for those who were enslaved as a means of control and dehumanization. Omar’s narrative is thus distinctive from those by other authors with similar experiences of enslavement, such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs, since they learned to read and write after emancipation. While in West Africa, Ibn Said had been a teacher and prolific scholar. He read the Qur’an and studied for twentyfive years first under his brother, Sheikh Muhammad Said, then from two other Muslim sheikhs.

In 1807, at thirty-seven years old, Ibn Said was enslaved by a raiding army and trafficked to Charleston, South Carolina, where he spent the next five decades of his life on plantations. He was first sold to a harsh and unsympathetic plantation owner named Johnson. In 1810, he escaped and walked north to Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he was recaptured and jailed for sixteen days. In jail, Ibn Said wrote in Arabic on the walls. John Owen’s daughter noticed the unfamiliar writing and brought him

to the attention of her father, who purchased Ibn Said for his brother, General James Owen of Bladen County.

While the property of General James Owen, Omar wrote his autobiography, Life, in formal Arabic in a West African (Maghribi) script in 1831. The autobiography itself is short, consisting only of fifteen handwritten pages, and it is preceded by a chapter from the Qur’an, Surat al-Mulk, which centers God’s absolute power through ownership. Unlike other contemporaneous slave narratives, the document was not edited by Ibn Said’s owner;

it is likely that Ibn Said’s ability to write in Arabic lent him a bit of cultural glamor and admiration from his master. As the only known surviving slave narrative written in Arabic in the United States, Ibn Said’s Life is a crucial document of and testament to not only Omar’s life in captivity but also to the broader presence of Arabic literacy and Muslim culture in early America.

Omar remained enslaved until his death around 1864, but his story lives on in Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels’ operatic retelling. The world premiere of Omar was on May 27, 2022, at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina. It was co-produced by a total of six opera companies, and it traveled to Los Angeles, California for the West Coast premiere by LA Opera in October 2022. The Carolina Performing Arts produced it in February 2023

in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Boston Lyric Opera’s Northeast premiere is in May 2023 and San Francisco Opera and Lyric Opera of Chicago will produce it within the next two years.

How do the many locations in which Omar is produced impact the memory of Omar Ibn Said’s life?

THE GENRE OF THE SLAVE NARRATIVE

“I

cannot write my

life.”

These mysterious words, which appear at the outset of Omar Ibn Said’s 1831 autobiographical narrative, prompt us to wonder, “what does it mean to tell one’s own story?” – or, more specifically, to have access to the language, materials, and institutions that make it possible for a life story to become part of the written historical record. How did Omar come to write his Life, and what compelled him to create this sparse, elusive document? How did his autobiography come to be a text that today’s readers can access at the click of a button? But more conceptual questions also arise: is it possible for a written text to convey the horrific violence of enslavement? What kind of constraints might an enslaved writer face, and what kind of rhetorical strategies could they use to assert their own agency regardless?

As the only surviving manuscript written by an enslaved person in Arabic within the United States, The Life of Omar Ibn Said has attracted much scholarly attention. At the same time, it’s important to note that the text is part of a broader tradition of Arabiclanguage writing in the Americas. An unknown number of other African-born enslaved people wrote in Arabic during the early nineteenth century, and texts by about a dozen of them have survived: for instance, Muhammad Kaba, born in Futa Jallon (now Guinea) and enslaved in Jamaica, wrote letters to other

enslaved Muslims about their shared faith; while Bilali Mohammed, born in Futa Jallon and enslaved first in the Bahamas and then in Georgia, offered written descriptions of Islamic prayer rituals and legal protocols. Omar, however, was the only one whose specifically autobiographical writings have survived to the present day. After Omar wrote his Life, parts of it were translated into English as early as Ajami.

In addition to writing in the Arabic language, many Muslims in Africa wrote in Ajami, a term which refers to the use of Arabic script to write in other languages. By using Ajami to write in their own indigenous languages, these authors created a written record of their lives and an important complement to orally transmitted knowledge. Enslaved Muslims in the Americas also used Ajami. For example, scholars recently learned that in 1838, a formerly enslaved man in Jamaica, Muhammad Kabā Saghanughu, used Ajami script to convey the sounds of English words in a letter to the island’s governor, in which he critiqued slavery and celebrated emancipation.

1848, and excerpts from the work circulated in print. A full translation appeared in the American Historical Review in 1925, but the original manuscript vanished until 1995, when it was found in a trunk and acquired by a research library. A digitized copy of the manuscript, acquired by the Library of Congress in 2017, can be accessed online via the Omar Ibn Said Collection When writing the opera’s libretto, Giddens and Abels based their work on a 2011 translation of the manuscript by Dr. Ala Alryyes.

Omar’s Life is also a slave narrative, a genre with its own rich literary and cultural history. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, fugitive and formerly enslaved people documented their experiences in texts intended to communicate slavery’s brutality, advocate for abolition, and assert the writer’s humanity. These were acts of testimony through which African Americans, under conditions of profound oppression, contributed to their own emancipation. Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Life of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789) described what he called the “horrors of a slave ship” in indelibly graphic detail.

Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845) communicated the shocking everyday violence of life on the plantation and established its author as one of the nineteenth century’s most profound writers and speakers. Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) drew attention to the sexual violence experienced by enslaved women.

As politically influential and rhetorically impressive as these texts were, they were also written under numerous constraints. White editors and publishers often prefaced enslaved authors’ words with attestations that

THE GENRE OF THE SLAVE NARRATIVE CONTINUED

these narratives were truly “authentic.” They encouraged – or forced – authors to adhere to certain stylistic and narrative conventions, such as a focus on hard facts rather than subjective feelings, or a posture of gratitude toward white abolitionists. In fact, many authors began their narratives with expressions of modesty similar to Omar’s, as if to communicate indebtedness to their editors and publishers. Due to these circumstances, it is essential that contemporary readers approach these texts not simply as “objective” historical sources, but rather as layered documents which conceal as much as they reveal about their narrators’ lives.

Omar’s Life, for example, says nothing about what he endured during the Middle Passage, and goes into little detail about what he experienced at the hands of his first master, a “small, weak and wicked man, called Johnson.” It is full of praise for his enslaver, John Owen – a “good man” who “never beats me nor scolds me.” There are flashes of emotion – asked if he would return to Charleston, Omar answers, “No, no, no, no, no, no, no” – but the text’s overall tone is measured, even reserved. Because Omar wrote in a language that his enslavers could not read, perhaps he had more agency than other enslaved people to write what he wished, and chose to focus on his faith, which was extremely meaningful to him. At the same time, if he intended to impress potential antislavery audiences, he may have

been compelled to emphasize his own literacy and piousness more than his suffering.

Given the limits of this text, the details of Omar’s experience will remain unknown – which may partially explain its appeal as a source text for a creative work. In his own slave narrative, Frederick Douglass mused on the power of enslaved people’s singing to communicate what words could not: “I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.” Although a twenty-first-century opera sounds very different from the spirituals Douglass describes, their influence is embedded in the musical lineage that has led to the composition of this opera. Ultimately, opera gives us a different way of accessing Omar’s narrative, considering its power and its limitations, and remaining attuned to the vitality of his story.

REFLECT:

What meanings do you think the intended audience for the original 1831 Arabic-language version of Omar’s narrative took away from reading it?

Take a look at the digitized version of Omar’s narrative.

What do you observe?

What surprises you or catches your attention?

DISCUSS:

How is reading a scholarly source about a subject – especially a traumatic subject like slavery – different from engaging with creative work about that subject?

What new understandings do contemporary scholars add when reading this text today in Arabic and English? intended Arabic-language from

What different meanings might the 1925 audience reading the English translation have learned?

MUSLIM LIFE IN EARLY AMERICA

Throughout Omar, the protagonist’s devotion to his Islamic faith is a central theme. From the first moments of the opera, he finds solace in his conviction that Allah will guide him toward the straight path, even when his future appears precarious. While Omar’s faith sets him apart in the context of the opera, Muslims actually comprised a significant portion of the enslaved population in early America. Islam had been present in West Africa as early as the eighth century, linking the region to the global Islamic world. The European demand for slaves generated by the rise of the transatlantic slave trade, coupled with a series of military conflicts within West Africa, created conditions in which vast numbers of Muslims in the region were forced into captivity. Muslim students, traders, and clerics (marabouts), in particular, traveled frequently, and they were exceptionally vulnerable to abduction by slavers.

Once they arrived in the Americas, West African Muslims faced both racial and religious oppression.

social mobility, and work toward their own emancipation. In some cases, their literacy skills enabled them to pursue more specialized work, such as bookkeeping, or even paid labor, such that they could eventually buy their own freedom. And by writing treatises, letters, and narratives for one another, enslaved Muslims maintained a sense of community. These acts of writing also provided opportunities for resistance: for example, they might copy verses from the Qur’an that denounced slavery as a means of protesting their own enslavement.

Scholars estimate that as many as 20% of enslaved people in the Americas were Muslims, but in a Christiandominated society, they struggled to maintain their religious identity. They were often forced to convert to Christianity or denied the opportunity to practice their faith. Despite these hostile circumstances, many enslaved Muslims maintained a commitment to Islam. Unlike European societies of the era, which tended to restrict literacy to men and members of elite classes, African Muslim cultures prioritized literacy for all, based on the belief that Arabic literacy equipped believers to fully comprehend the Qur’an and lead devout lives. Enslaved Muslims carried this knowledge with them, and they persisted in reading the Qur’an and producing Arabic writing – activities which ultimately helped them not only to maintain their religious practices, but also helped them to resist enslavement, attain a degree of

Enslaved Muslims also found ways to maintain a relationship to Islam via customs and rituals. For example, they engaged in harvest rituals which involved nightlong chanting; made offerings of food and drink to the ancestors called saraka; and created a dance known as the “ring shout,” which echoes the practice of circling the Kaaba in Mecca. These practices, many of which have survived in some form to the present day, have become part of enslaved Muslims’ cultural legacy.

REFLECT:

What kind of customs and rituals are meaningful in your culture and religion? How do they create a sense of community? Do you practice these customs and rituals differently from how your parents and grandparents did?

Listen to an example of the ring shout, “I Come To Tell You,” recorded by the Georgiabased McIntosh County Shouters.

THE MELODIES OF ISLAMIC PRAYER

discuss:

Are there melodic elements of your culture or religion that may not be necessarily described as music? How does that impact how you hear and understand those aspects of your culture? How does music encourage intention and reflection in your culture or religion?

Omar opens with the titular character in a state of prayer. He begins with the phrase, “Bismillah hir rahman nir raheem ( �حرلا نحمرلا لهلا سمب ) [In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful].” the beginning of what is often considered to be the first verse of the Qur’an. This phrase is commonly stated by Muslims before starting a task or an action to clarify their intentions and ask for Allah’s blessings as they embark on their endeavor. In Omar, the phrase serves double duty, first setting the stage for the task of performing the opera while illustrating Omar’s faith and prayer to Allah for help. Sung a cappella, or without instruments, Omar’s voice sonically demonstrates the beautifully ornamented sustained lines of Islamic prayer, sung with delicate trills that embellish the ends of each phrase. Though incredibly sonorous, Islamic prayers are not considered musical in the Western understanding. As methods of recitation, both the call to prayer (adhān) and the recitation of the Qur’an are distinct from singing; conversely, musiqa, the Arabic term for music, has often been applied to instrumental music or vocal music with instrumental accompaniment. While there is not any text in the Qur’an or in the traditions of the Prophet (hadīth) that explicitly forbids music, Muslim communities have frequently been mischaracterized as being against music, since some orthodox communities believe that musiqa will lead individuals astray from their devotional life and towards deviant behavior. Scholarly and public debates on the relationship between Islam and music continue today. However, the lack of consensus on the status of music in Islam has allowed forms of popular, secular, and Islamic devotional music to flourish and coexist.

The adhān can be heard up to five times a day, and it signals to the Muslim community the time to pray. Traditionally the adhān is given by the Mu’adhdhin, who climbs the minaret of mosques and projects his voice to the community surrounding the mosque. Today, the adhān can be heard through media and from loudspeakers on the minarets of mosques. The adhān involves an affirmation of Allah and a profession of faith in Allah’s teachings in Arabic, and while there is no fixed melody or meter to the call to prayer, there is careful attention paid to the clarity of the text. Each line of the adhān is recited with long lines based on variations of the Middle Eastern maqam melodic system, and lines can finish with melismatic embellishments, executed by extending one syllable over multiple notes. Above all, both the adhān and the prayer serve to express tawhid, or the idea of “unity with God.”

Listen to a few examples of the adhān

OPERAS BY BLACK COMPOSERS: A TIMELINE

OPERAS BY BLACK COMPOSERS: A TIMELINE

African American composers have written themselves and their stories, opera by opera, into American musical life. In a society hostile to the very idea of their existence, Black operatic composers created a repertoire of remarkable breadth and depth. They drew upon a diverse set of musical influences, from ragtime to the spirituals to Verdi to jazz; they wrote operetta and Wagnerian dramas, tragicomic love stories and historical epics. (It is worth noting that these composers’ decisions to work across a variety of musical genres often stemmed as much from necessity as from creative choice: since they regularly faced insurmountable hurdles in getting their work published and performed, they took on whatever work they could in order to make ends meet.) Long relegated to the status of exceptions, curiosities, and aberrations, these works constitute an unduly overlooked corner of the American musical past.

This timeline contains some examples of operas by Black composers, from one written just a few decades after Omar’s autobiography was published to works written in the present day. It is far from comprehensive; instead, it gives a sense of how expansive the tradition of Black operatic composition is, and how many people have contributed to its creation.

1868

John Thomas Douglass (composer and librettist), Virginia’s Ball. Virginia’s Ball is thought to be the first opera by an African American composer. Unfortunately, the score and libretto have been lost.

Louisa Melvin Delos Mars (composer and librettist), Leoni, The Gypsy Queen. Delos Mars was likely the first African American woman to write an opera. Leon, The Gypsy Queen was produced in Providence, Rhode Island; this score, too, is sadly lost.

1889

Harry Lawrence Freeman

The Martyr. Freeman over the course of his first compositions, is ancient Egypt.

William Grant Still and Langston Hughes/Verna Arvey, Troubled Island. Like Ouanga!, Troubled Island takes as its subject the Haitian Revolution. It was produced by New York City Opera in 1949, marking the first production of an opera by a Black composer by a major company. “I Dream a World” from Troubled Island.

1932

Clarence Cameron White and John Frederick Matheus, Ouanga! In the 1920s, violinist-composer White and scholar-poet Matheus traveled to Haiti to collect material for this opera about Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a leader of the Haitian Revolution.

1949

Shirley Graham (composer and librettist), Tom-Tom. Graham’s epic opera, a diasporic tale of African American history which spans from the distant past to 1930s Harlem, premiered in a Cleveland baseball stadium in 1932 before an audience of thousands. Listen to excerpts from Tom-Tom here

Dorothy Rudd Moore’s opera tableaus. more than was a moment shoulder.

3 of Frederick

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Paul Laurence Dunbar, Dream Lovers A collaboration between a famed Afro-British composer and an equally well-known African American poet, Dream Lovers is a romantic tale set in Madagascar.

Freeman (composer and librettist), wrote more than twenty operas career. The Martyr, among his a Wagner-inspired drama set in

The score for Scott Joplin’s opera Treemonisha, published in 1911. Creativity Commons.

Scott Joplin (composer and librettist), Treemonisha. Joplin was known best for his ragtime compositions, but he was also fascinated by opera. He was unable to stage a performance of his second opera, Treemonisha, during his lifetime, but it has since been produced many times.

Nkeiru Okoye (composer and librettist), Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed That Line to Freedom. Okoye became interested in writing a piece about Tubman while living in Baltimore (Tubman’s birthplace), and spent years researching the heroic abolitionist’s life. The opera not only narrates Tubman’s experiences – first in slavery, then as a rescuer of enslaved people –but also conveys the historical soundscape of Tubman’s own time.

Harriet Tubman.

Anthony Davis and Thulani Davis, X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X. Written by composer Anthony Davis and his cousin, the poet and scholar Thulani Davis, this opera explores the life of one of the most influential figures in the twentieth-century Black freedom struggle. X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X

Rudd Moore (composer and librettist), Frederick Douglass. opera narrates its protagonist’s life via a series of dramatic The composer recalls that as she worked on the piece for than a decade, she felt a deep affinity with her subject: “there moment which was as though [Douglass] were sitting around my It was something just uncanny.” An excerpt from Act 2, Scene Frederick Douglass.

Terence Blanchard and Kasi Lemmons, Fire Shut Up in My Bones. Based on a memoir by author and columnist Charles Blow, Fire Shut Up in My Bones premiered in St. Louis in 2019 and became the first opera by a Black composer and librettist to be staged at the Metropolitan Opera in 2021. “Peculiar Grace” from Fire Shut Up in My Bones.

REFLECT: Listen to two or three excerpts from these operas. What similarities and differences do you notice among the works? Have you heard operas by Black composers before, on recordings or in performance? If so, what was the context? If not, why do you think that is?

FINDING THE MUSIC IN OMAR’S LIFE

At the end of the opera, Omar begins to write his autobiography in Arabic, praising the beauty of the world around him in Allah’s name.

Representing the origins of its own source material, the opera envisions the power of writing down the story of one’s life. By taking the contents of Omar Ibn Said’s Life as both inspiration and operatic source material, Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels join a number of recent creators who have turned to artifacts of the archive and the intimately personal narratives of diaries and memoirs as the foundations for new opera; one prominent example is Terence Blanchard and Kasi Lemmons’ Fire Shut Up in My Bones, the first opera by a Black composer and Black librettist staged at the Met. Fire opened the Metropolitan Opera’s 2021-2022 season in a historic milestone for American opera, and it is based on a memoir of the same name by New York Times columnist and author Charles M. Blow. Navigating the blurry relationship between dramatic life events, historical fact, and theatrical

representations, these operas based on autobiographical writings open opportunities to explore what sometimes is absent or difficult to discern from the page: the nuance of human experience.

Of course, real life doesn’t lend itself to operatic adaptation easily. When a memoir is transformed into an opera, the operatic version often takes its own form; not everything can be staged exactly as it was written in the memoir. Memoirs are often written in an episodic narrative arc, making each one a unique challenge to narrativize on the opera stage: when events are presented as episodes within a chronological timeline, there may not be a clear narrative arc for an opera to follow. Episodes can read as vivid vignettes rather than a time bound drama with a climax and resolution.

To fit the operatic stage, composers and librettists may need to edit, condense, expand, or even exaggerate specific moments. We can see the result of this expanded imagination in the Act I Middle Passage scene. Omar only briefly mentions the Middle Passage in his autobiographical account. He notes that the journey was a month and a half

long, but gives no detail about the difficulties or the suffering he and his fellow captives endured. For the operatic retelling of Omar’s story, Giddens and Abels expand the journey into an entire scene to better situate the audience in the experience of capture and displacement. Additionally, Omar navigates issues of translation that make the opera accessible to American audiences. While the original memoir was written in Arabic, we experience both Arabic and English in the opera, illustrating the ways in which Omar was asked to navigate living in a world in which he did not speak the primary language.

At the same time, one of the many strengths of opera is its ability to convey the drama of its characters’ emotional journeys. A memoir is a particularly rich kind of source material for opera because of the access it affords to the author’s interiority and emotional reflections. Readers of memoirs can learn about the author’s intimate thoughts and feelings of a particular moment in time; a memoir is necessarily an incomplete document of someone’s life, told from a singular perspective. We might think of an opera based on a memoir as a three-dimensional rendering of a previously two-dimensional medium, musicalizing the emotional depth of the written document. The composers are tasked with animating the silent world of text through sound. Whereas in Omar’s

Lost In Translation.

In Omar, translation plays many roles. The opera is based on an autobiography that was first written in Arabic and later translated into English, and while the opera is primarily in English, it features both languages. On another level , the opera asks us to think about what happens when translation is impossible. In one of the opera’s most moving scenes, Omar faces the horrors of the Middle Passage while crammed alongside fellow captives. They attempt to speak to each other, but communication is futile. As they have been taken from different villages, they do not share a language. “I cannot understand you,” one man cries with despair. Once ashore, Omar will struggle to navigate the English-speaking world he has been forced into. In light of all that he has lost, he holds onto language as a key source of identity, finding solace in the Arabic speech and script that connects him to his home and family.

Life, we were able to read Omar’s sole authorial voice in the text, in the opera, we also now hear the musical authorial voices of Giddens and Abels.

The music of Omar ranges from swirling lyrical hymns that accompany introspective moments to stinging brass, driving the terror and violence of the raid on Omar’s village. We also can hear specific musical genres that illustrate the social status and background of each character. For example, at the Charleston Slave Market in Act I scene 3, the orchestra reinforces the white auctioneer’s European roots and higher class life with music written in the style of a recitative. Recitative is the musical term for language that is sung in an operatic dialogue; often the orchestra has to follow the singer closely, playing mostly sustained background chords, and it only interjects the singer’s words with a few notes. In Omar, the auctioneer showcases his authority and social power by leading the orchestra through this recitative before breaking into a waltz (listen for the characteristic oompah-pah rhythms!), illustrating his gleeful excitement at the proceedings of the Charleston Slave Market.

Another compositional element commonly used in opera is the chorus. In many operas, the ensemble, or all of the other singers on stage who do not perform a named role, showcases the communities that surround the protagonists, and the ensemble often tells us more about the chronological moment the opera depicts. In the operatic retelling of Omar’s life, the audience also witnesses fleeting moments in other enslaved people’s lives. Portraying the various communities of which Omar is a member, the ensemble expands the scope of the opera. As we go on the journey of Omar’s life, we also experience the ways in which communities come together to express their emotions, at times singing only on open syllables “ah” to illustrate a sense of collective grief.

But as composers and musicians whose past compositions have not typically been in the world of opera, Giddens and Abels invite us to listen to an array of musical styles that expand the traditional musical parameters of the genre. In addition to the more standard operatic musical techniques mentioned above, we also can hear the distinctive influence of spirituals, sung by the enslaved people on the Johnson Plantation in Act I scene 4, and the hoedown music in Act II scene 2 on the Owen plantation, illustrating the Black origins of the American folk musics. In this way, Giddens and Abels bring their perspectives and musical expertise into dialogue with Omar’s words, interpreting the source material to reimagine his story for twenty-first-century audiences.

Omar Ibn Said’s memoir is a monumental document to inspire an opera, not only because of what we can learn from Omar’s words, but also because of what we might further imagine of the early nineteenth century. When so little remains from the enslaved people in the United States, this memoir is vital to our ability to understand those who were systemically oppressed and silenced. In the opera, Omar is urged to “Tell your story,” a directive that is amplified through their operatic setting by Giddens and Abels. Blending musical styles and traversing the full range of the voice, Giddens and Abels interpret Omar’s words into a new work of art. To watch the opera then is to take a journey back through time and to listen to not just one voice, but rather a chorus of voices, sounding our shared American histories.

DISCUSS:

What other creative forms can memoirs serve as the source material for? How does the medium change your experience of the narrative or the characters? What artistic medium would you use to tell your story and why?

If you were to adapt a memoir to an opera, what memoir would you choose, and how would you re-imagine it for the stage?

RESOURCES

Other Study Guides

Opera for Educators - “Omar” Guide | LA Opera - Official Site

Omar-workbook_2022_for-web.pdf (spoletousa.org)

Podcasts

Episode 6: The Soul of Music: Rhiannon Giddens excavates the past (nationalgeographic.com)

“The Long Journey of Omar Ibn Said.” Library of Congress, 2019.

Organizations

Abolitionist History – Muslim Justice League

Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative (muslimarc.org)

WEST AFRICAN RESEARCH ASSOCIATION | WARA – Promoting scholarly exchange with West Africa, USA, and the global community.

Books

A Muslim American Slave: The Life of Omar Ibn Said. Translated from the Arabic, edited, and with an introduction by Ala Alryyes. University of Wisconsin Press, 2011.

Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. By Sylviane A. Diouf. New York University Press, 2013.

Music in the World of Islam: A Socio-cultural Study. By Amnon Shiloah. Routledge, 1994.

Websites

Omar Ibn Said Collection at the Library of Congress.

“Educated and Enslaved: The Journey of Omar Ibn Said.” By Benny Seda-Galarza. Library of Congress.

Articles

“African Muslims in Early America: Religion, Literacy, and Liberty.” National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“Sound and Community in the Muslim Call for Prayer.” By Joseph Progler

Smithsonian Folkways Magazine.

GUIDE AUTHORS

Lucy Caplan is Lecturer and Assistant Director of Studies in History and Literature at Harvard University. She holds a Ph.D. in American Studies and African American Studies from Yale University.

Allison Chu is a Ph.D. candidate in Music History at Yale University. Her research focuses on the intersection of identity and opera in the twenty-first century.

LISTEN UP!

Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels were inspired by many different musical influences when composing Omar. Here are two examples:

The overture to Omar is based on a West African tune, “Koromanti.” Listen to this adaptation for fretless banjo and djembe. https://soundcloud.com/dukeuniversity/koromanti-2-adapted-forfretless-banjo-and-djembe?in=dukeuniversity/sets/musical-passage&utm_source=clipboard&utm_ medium=text&utm_campaign=social_sharing

The “Hoedown” in Act Two, Scene 2 of Omar, is based on the tune “Old Corn Likker,” performed here by Rhiannon Giddens and Dom Flemons: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pemofre-eBk

Listen to examples of Giddens’ and Abels’ previous work. As you watch and listen to Omar, what echoes of Rhiannon Giddens’ and Michael Abels’ past works can you hear in this opera?

Rhiannon Giddens, “Calling Me Home (with Francesco Turrisi)”

https://open.spotify.com/track/2C6qZqsYHMFuY0GopknQRr?si=3835df3bae4a4c58

Rhiannon Giddens, “At the Purchaser’s Option”

https://open.spotify.com/track/5RmAtT0VaKttU0Eybo6ZWA?si=303608b58de24b28

Michael Abels, “Isolation Variation”

https://open.spotify.com/track/01J3ZgHOWdCiMfqSBTaEqS?si=c47d0efee3474f9a

Michael Abels, Soundtrack to Get Out

https://open.spotify.com/album/0L7VtXWMySVyhePPAtRlAN?si=wA4prGkuSQ2ooCKIlr0bpA

Slave narratives were written documents, but enslaved people also created music that protested their condition and advocated for abolition. Both were recorded in 2022 for the album Songs of Slavery and Emancipation, a collection of music from the abolitionist movement.

Listen here to “A Song for Freedom,” an 1844 song which adds abolitionist lyrics to the minstrel tune “Dandy Jim.”

https://open.spotify.com/track/4N6nQJWYexdOnSpQgwP3Xa?si=a8c6719c8fa44c40

“Nat Turner” tells of the famed leader of a slave rebellion which occurred in 1831 – the same year Omar Ibn Said wrote his narrative.

https://open.spotify.com/track/4hcuTvxxYDuB3BV6p0RKaE?si=0cb32ab04b4944af

GENERAL QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR LISTENING

• What instruments do you hear?

• How fast is the music? Are there sudden changes in speed? Is the rhythm steady or unsteady?

• Key/Mode: Is it major or minor? (Does it sound bright, happy, sad, urgent, dangerous?)

• Dynamics/Volume: Is the music loud or soft? Are there sudden changes in volume (either in the voice or orchestra)?

• What is the shape of the melodic line? Does the voice move smoothly or does it make frequent or erratic jumps? Do the vocal lines move noticeably downward or upward?

• Does the type of voice singing (baritone, soprano, tenor, mezzo, etc.) have an effect on you as a listener?

• Do the melodies end as you would expect or do they surprise you?

• How does the music make you feel? What effect do the above factors have on you as a listener?

• What is the orchestra doing in contrast to the voice? How do they interact?

• What kinds of images, settings, or emotions come to mind? Does it remind you of anything you have experienced in your own life?

• Do particularly emphatic notes (low, high, held, etc.) correspond to dramatic moments?

• What type of character fits this music? Romantic? Comic? Serious? Etc.

THE HISTORY OF OPERA

People have been telling stories through music for millennia throughout the world. Opera is an art form with roots in Western Europe that is over 400 years old. Here is a brief timeline of its lineage. RENAISSANCE

1600-1750

A NOTE ABOUT LIBERETTI

In opera, the libretto has often been sourced from plays, novels, famous myths, and even films, and it communicates both the dialogue and the events of the story. The term libretto comes from the Italian word for book, “libro,” and can refer to both the words that are sung in an opera or the printed version of the words in the program or in a separate book. (This is also why in Musical Theater, the script is referred to as “the book.”)

Up until the eighteenth century, operas were associated with the name of the work’s librettist (the author of the text) rather than the composer, and typically the libretto was written before the composer began writing any music. However, when creating a new opera in the twenty-first century, the librettist often collaborates with the composer. Typically, the librettist’s name is listed immediately following the composer’s name on a program. Some of the most famous librettists have had a single text set in multiple operas by different composers, as in the case of Pietro Metastasio in the eighteenth century, or have established longer collaborations with a composer, such as in the case of Lorenzo Da Ponte and his libretti for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

RENAISSANCE

1573 The Florentine Camerata was founded in Italy, devoted to reviving ancient Greek musical traditions, including sung drama.

1598 Jacopo Peri, a member of the Camerata, composed the world’s first opera – Dafne, reviving the classic myth.

1607 Claudio Monteverdi i, (1567-1643) wrote the first opera to become popular, Orfeo, making him as the premier opera composer of his day and bridging the gap between Renaissance and Baroque music. His works are still performed today.

1637 The first public opera house, Teatro San Cassiano, was built in Venice, Italy.

BAROQUE (1600-1750)

1673 Jean Baptiste Lully (1632-1687) an Italianborn composer, brought opera to the French court, creating a unique style, tragédie en musique, that better suited the French language. Blurring the lines between recitative and aria, he created fast-paced dramas to suit the tastes of French aristocrats.

1712 George Frederic Handel

1689 Henry Purcell’s 1659-1695) simple and elegant chamber opera, Dido and Aeneas, premiered at Josias Priest’s boarding school for girls in London.

(1685-1759), a German-born composer, moved to London, where he found immense success writing intricate and highly ornamented Italian opera seria (serious opera). Ornamentation refers to stylized, fast-moving notes, usually improvised by the singer to make a musical line more interesting and to showcase their vocal talent.

CLASSICAL (1730-1820)

1805 Ludwig van Beethoven

(1770-1827) although a prolific composer, wrote only one opera, Fidelio. The extremes of musical expression in Beethoven’s music pushed the boundaries in the late Classical period and inspired generations of Romantic composers.

1750s A reform movement, led by Christoph Gluck (1714-1787), rejected the flashy ornamented style of the Baroque in favor of simple, refined music to enhance the drama. simplicity refined to enhance the drama.

1816

Gioacchino Rossini

1767

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) wrote his first opera at age 11, beginning his 25-year opera career. Mozart mastered, then innovated in several operatic forms. He wrote opera serias, including La Clemenza di Tito, and opera buffas (comedic operas) like Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). He then combined the two genres in Don Giovanni, calling it dramma giocoso (comedic drama). Mozart also innovated the Singspiel (German sung play), featuring a spoken dialogue, as in Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute).

1792-1868) composed Il Barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), becoming the most prodigious opera composer in Italy by age 24. He wrote 39 operas in 20 years. A new compositional style created by Rossini and his contemporaries, including Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini, would, a century later, be referred to as bel canto (beautiful singing). Bel canto compositions were inspired by the nuanced vocal capabilities of the human voice and its expressive potential. Composers employed strategic use of register, the push and pull of tempo (rubato), extremely smooth and connected phrases (legato), and vocal glides (portamento).

1853 Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) completed La Traviata, a story of love, loss, and the struggle of average people, in the increasingly popular realistic style of verismo. Verdi enjoyed immense acclaim during his lifetime, while expanding opera to include larger orchestras, extravagant sets and costumes, and more highly trained voices.

ROMANTIC (1790-1910)

The Golden Age of Opera

1842 Inspired by the risqué popular entertainment of French vaudeville, Hervé created the first operetta, a short comedic musical drama with spoken dialogue. Responding to popular trends, this new form stood in contrast to the increasingly serious and dramatic works at the grand Parisian opera house. Opéra comique as a genre was often not comic, rather realistic or humanistic. Grand Opera, on the contrary, was exaggerated and melodramatic.

1865 Richard Wagner’s (1813-1883) Tristan und Isolde was the beginning of musical Modernism, pushing the use of traditional harmony to its extreme. His massively ambitious, lengthy operas, often based in German folklore, sought to synthesize music, theater, poetry, and visuals in what he called a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). The most famous of these was an epic four-opera drama, Der Ring des Nibelungen, which took him 26 years to write and was completed in 1874.

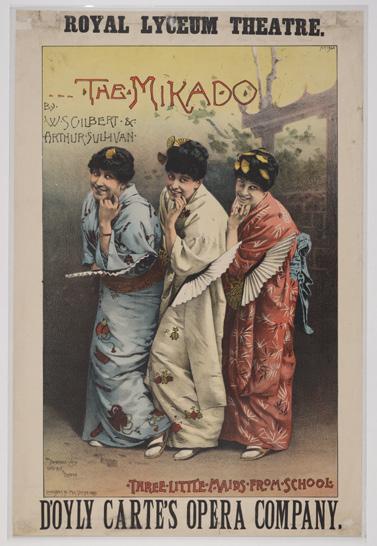

1871 Influenced by French operetta, English librettist W.S. Gilbert (1836-1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) began their 25-year partnership, which produced 14 comic operettas including The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado. Their works inspired the genre of American musical theater.

ROMANTIC (1790-1910)

1874

Johann Strauss II, (1825-1899)

influenced largely by his father, with whom he shared a name and talent, composed Die Fledermaus, popularizing Viennese musical traditions, namely the waltz, and shaping operetta

1896

Giacomo Puccini’s II, (1858-1924) La Bohème captivated audiences with its intensely beautiful music, realism, and raw emotion. Puccini enjoyed huge acclaim during his lifetime for his works.

1911 Scott Joplin, (1868-1917) “The King of Ragtime,” wrote his only opera, Treemonisha, which was not performed until 1972. The work combined the European lateRomantic operatic style with African American folk songs, spirituals, and dances. The libretto, also by Joplin, was written at a time when literacy among African Americans in the southern United States was rare.

1927 American musical theater, commonly referred to as Broadway, was taken more seriously after Jerome Kern’s (1885-1945) Show Boat, words by Oscar Hammerstein, tackled issues of racial segregation and the ban on interracial marriage in Mississippi.

1922

Alan Berg, (1885-1935) composed the first completely atonal opera, Wozzeck, dealing with uncomfortable themes of militarism and social exploitation. Wozzeck is in the style of 12-tone music or Serialism. This new compositional style, developed in Vienna by composer Arnold Schoenberg (18741951), placed equal importance on each of the 12 pitches in a scale, removing the sense of the music being in a particular key.

1945 British composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) gained international recognition with his opera Peter Grimes. Britten, along with Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), was one of the first British opera composers to gain fame in nearly 300 years.

20TH CENTURY

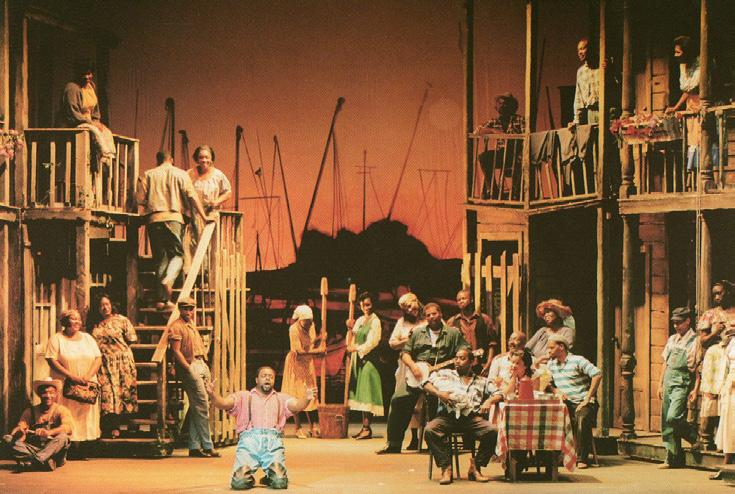

1935 American composer George Gershwin (1898-1937), who was influenced by African American music and culture, debuted his opera, Porgy and Bess, in Boston, MA with an all African American cast of classically trained singers. His contemporary, William Grant Still (1895-1978), a master of European grand opera, fused that with the African American experience and mythology. His first opera, Blue Steel premiered in 1934, one year before Porgy and Bess.

1987

John Adams (b. 1947) composed one of the great minimalist operas, Nixon in China, the story of Nixon’s 1972 meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong. Musical Minimalism strips music down to its essential elements, usually featuring a great deal of repetition with slight variations.

1986

Today

1957

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), known for synthesizing musical genres, brought together the best of American musical theater, opera, and ballet in West Side Story—a reimagining of Romeo and Juliet in a contemporary setting.

Anthony Davis (b. 1951) premiered his first of many operas, X, The Life and Time of Malcom X which reclaims stories of Black historical figures within the theater space. He incorporated both the orchestral and vocal techniques of jazz and classical European opera in his score for a distinctly American sound, and a fully realized vision of how jazz and opera are in conversation within a work.

Still a vibrant evolving art form, opera attracts contemporary composers such, Philip Glass (b. 1937), Jake Heggie (b. 1961), Terence Blanchard (b. 1962), Ellen Reid (b. 1983) and many others. Composers continue to be influenced by present and historical musical forms in creating new operas that explore current issues or reimagine ancient tales.

THE SCIENCE AND ART OF OPERA

WHY DO OPERA SINGERS SOUND LIKE THAT?

Opera is unique among forms of singing in that singers are trained to be able to sing without amplification, in large theaters, over an entire orchestra, and still be heard and understood! This is what sets the art form of opera apart from similar forms such as musical theater. To become a professional opera singer, it takes years of intense physical training and constant practice—not unlike that of a ballet dancer—to stay in shape. Additionally, while ballet dancers can dance through pain and illness, poor health, especially respiratory issues and even allergies, can be severely debilitating for a professional opera singer. Let’s peak into some of the science of this art form.

How the Voice Works

Singing requires different parts of the body to work together: the lungs, the vocal cords, the vocal tract, and the articulators (lips, teeth, and tongue). The lungs create a flow of air over the vocal cords, which vibrate. That vibration is amplified by the vocal tract and broken up into words by consonants produced by the articulators.

BREATH:

Any good singer will tell you that good breath support is essential to produce quality sound. Breath is like the gas that goes into your car. Without it, nothing runs. In order to sing long phrases of music with clarity and volume, opera singers access their full lung capacity by keeping their torso elongated and releasing the lower abdomen and diaphragm muscles, which allows air to enter into the lower lobes of the lungs. This is why we associate a certain posture with opera singers. In the past, many operas were staged with singers standing in one place to deliver an entire aria or scene, with minimal activity. Modern productions, however, often demand a much greater range of movement and agility onstage, requiring performers to be physically fit, and disproving the stereotype of the “park and bark.”

VIBRATION:

If you run your fingers along your throat, you will feel a little lump just underneath your chin. That is your “Adam’s Apple,” and right behind it, housed in the larynx (voice-box), are your vocal cords. When air from the lungs crosses over the vocal cords it creates an area of low pressure (Google The Bernoulli Effect), which brings the cords together and makes them vibrate. This vibration produces a buzz. The vocal chords can be lengthened or shortened by muscles in the larynx, or by increasing the speed of air flow. This change in the length and thickness of the vocal cords is what allows singers to create different pitches. Higher pitches require long, thin cords, while low pitches require short, thick ones. Professional singers take great pains to protect the delicate anatomy of their vocal cords with hydration and rest, as the tiniest scarring or inflammation can have noticeable effects on the quality of sound produced.

RESONANCE: ARTICULATION:

Without the resonating chambers in the head, the buzzing of the vocal cords would sound very unpleasant. The vocal tract, a term encompassing the mouth cavity, and the back of the throat, down to the larynx, shapes the buzzing of the vocal cords like a sculptor shapes clay. Shape your mouth in an ee vowel (as in eat), then sharply inhale a few times. The cool sensation you feel at the top and back of your mouth is your soft palate. The soft palate can raise or lower to change the shape of the vocal tract. Opera singers always strive to sing with a raised soft palate, which allows for the greatest amplification of the sound produced by the vocal cords. Different vowel sounds are produced by raising or lowering the tongue. Say the vowels: ee, eh, ah, oh, oo and notice how each vowel requires a slightly lower tongue placement. This area of vocal training is particularly difficult because none of the anatomy is visible from the outside!

The lips, teeth, and tongue are all used to create consonant sounds, which separate words into syllables and make language intelligible. Consonants must be clear and audible for the singer to be understood. Because opera singers do not sing with amplification, their articulation must be particularly good. The challenge lies in producing crisp, rapid consonants without interrupting the connection of the vowels (through the controlled exhale of breath) within the musical phrase.

Perfecting every element of this complex singing system requires years of training and is essential for the demands of the art form. An opera singer must be capable of singing for hours at a time, over the top of an orchestra, in large opera houses, while acting and delivering an artistic interpretation of the music. It is complete and total engagement of mental, physical, and emotional control and expression. Therefore, think of opera singers as the Olympic athletes of the stage, sit back, and marvel at what the human body is capable of!

Different Voice Types

Opera singers are cast into roles based on their tessitura (the range of notes they can sing comfortably). There are many descriptors that accompany the basic voice types, but here are some of the most common ones:

Bass:

The lowest voice, basses often fall into two main categories: basso buffo, which is a comic character who often sings in lower laughing-like tones, and basso profundo, which is as low as the human voice can sing! Doctor Bartolo is an example of a bass role in The Barber of Seville by Rossini.

Baritone:

A middle-range lower voice, baritones can range from sweet and mild in tone, to darker dramatic and full tones. A famous baritone role is Rigoletto in Verdi’s Rigoletto. Baritones who are most comfortable in a slightly lower range are known as Bass-Baritones, a hybrid of the two lowest voice types.

Tenor:

The highest of the lower range voices; tenors often sing the role of the hero. One of the most famous tenor roles is Roméo Gounod’s Roméo et Juliet. Occasionally men have cultivated very high voices singing in range similar to a mezzo-soprano but using their falsetto. Called the Countertenor, this voice type is often found in Baroque music. Countertenors replaced castrati in the heroic lead roles of baroque opera after the practice of castration was deemed unethical.

One Roméo in men in a using this music. heroic practice

Each of the voice types (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, baritone, bass) also tends to be sub-characterized by whether it is more Lyric or Dramatic in tone. Lyric singers tend toward smooth lines in their music, sensitively expressed interpretation, and flexible agility. Dramatic singers have qualities that are attributed to darker, fuller, richer note qualities expressed powerfully and robustly with strong emotion. While its easiest to understand operatic voice types through these designations and descriptions, one of the most exciting things about listening to a singer perform is that each individual’s voice is essentially unique, thus each singer will interpret a role in an opera in a slightly different way.

Contralto:

The lowest of the higher treble voices have an even lower range that overlaps with the highest tenor’s range.. This voice type is more rare and they often play male characters, referred to in opera as trouser roles.

Mezzo-Soprano:

Somewhat equivalent to an alto role in a chorus, mezzo-sopranos (mezzo translated as “middle”) are known for their full and expressive qualities. While they don’t sing frequencies quite as high as sopranos, their ranges do overlap, and it is a “darker” tone that sets them apart. One of the most famous mezzosoprano lead roles is Carmen in Bizet’s Carmen.

Soprano:

The highest voice; some sopranos are designated as coloratura as they specialize in being able to sing very fastmoving notes that are very high in frequency and light in tone, often referred to as “color notes.” One of the most famous coloratura roles is The Queen of the Night in Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

The Physics of Opera Singers

What is it about opera singers that allows them to be heard above the orchestra? It’s not that they simply singing louder. The qualities of sound have to do with the relationship between the frequency (pitch) of a sound, represented in a unit of measurement called hertz, and its amplitude, measured in decibels, which the ear perceives as loudness. Only artificially produced sounds, however, create a pure frequency and amplitude (these are the only kind that can break glass). The sound produced by a violin, a drum, a voice, or even smacking your hand on a table, produces a fundamental frequency as well as secondary, tertiary, etc. frequencies known as overtones, or as musicians call them, harmonics

For instance, the orchestra tunes to a concert “A” pitch before a performance. Concert “A” has a frequency of about 440 hertz, but that is not the only pitch you will hear. Progressively softer pitches above that fundamental pitch are produced in multiples of 440 at 880hz, 1320hz, 1760hz, etc. Each different instrument in the orchestra, because of its shape, construction, and mode in which it produces sound, produces different harmonics. This is what makes a violin, for example, have a different color (or timbre ) from a trumpet. Generally, the harmonics of the instruments in the orchestra fade around 2500hz. Overtones produced by a human voice—whether speaking, yelling, or singing— are referred to as formants

As the demands of opera stars increased, vocal teachers discovered that by manipulating the empty space within the vocal tract, they could emphasize higher frequencies within the overtone series—frequencies above 2500hz. This technique allowed singers to perform without hurting their vocal cords, as they are not actually singing at a higher fundamental decibel level than the orchestra. Swedish voice scientist, Johann Sundberg, observed this phenomenon when he recorded the world-famous tenor Jussi Bjoerling in 1970. His research showed multiple peaks in decibel level, with the strongest frequency (overtone) falling between 2500 and 3000 hertz. This frequency, known as the singer’s formant , is the “sweet spot” for singers so that we hear their voices soaring over the orchestra into the opera house night after night.

A Resonant Place

The final piece of the puzzle in creating the perfect operatic sound is the opera house or theater itself. Designing the perfect acoustical space can be an almost impossible task, one which requires tremendous knowledge of science, engineering, and architecture, as well as an artistic sensibility. The goal of the acoustician is to make sure that everyone in the audience can clearly understand the music being produced onstage, no matter where they are sitting. A perfectly designed opera house or concert hall (for non-amplified sound) functions almost like gigantic musical instrument.

Reverberation is one key aspect in making a singer’s words intelligible or an orchestra’s melodies clear. Imagine the sound your voice would make in the shower or a cave. The echo you hear is reverberation caused by the large, hard, smooth surfaces. Too much reverberation (bouncing sound waves) can make words difficult to understand. Resonant vowel sounds overlap as they bounce off of hard surfaces and cover up quieter consonant sounds. In these environments, sound carries a long way but becomes unclear or, as it is sometimes called, wet as if the sound were underwater. Acousticians can mitigate these effects by covering smooth surfaces with textured materials like fabric, perforated metal, or diffusers, which absorb and disperse sound. These tools, however, must be used carefully, as too much absorption can make a space dry – meaning the sound

onstage will not carry at all and the performers may have trouble even hearing themselves as they perform. Imagine singing into a pillow or under a blanket.

The shape of the room itself also contributes to the way the audience perceives the music. Most large performance spaces are shaped like a bell –small where the stage is and growing larger and more spread out in every dimension as one moves farther away. This shape helps to create a clear path for the sound to every seat. In designing concert halls or opera houses, big decisions must be made about the construction of the building based on acoustical needs. Even with the best planning, the perfect acoustic is not guaranteed, but professionals are constantly learning and adapting new scientific knowledge to enhance the audience’s experience.

Notes to Prepare for the Opera

You will see a full dress rehearsal – an insider’s look into the final moments of preparation before an opera premieres. The singers will be in full costume and makeup, the opera will be fully staged, and an orchestra will accompany the singers, who may choose to “mark,” or not sing in full voice, to save their voices for the performances. A final dress rehearsal is often a complete run-through, but there is a chance the director or conductor will ask to repeat a scene or section of music. This is the last opportunity the performers have to rehearse with the orchestra before opening night, and they therefore need this valuable time to work.

The following will help you better enjoy your experience of a night at the opera:

• Arrive on time! Latecomers will be seated only at suitable breaks in the performance and often not until intermission.

• Dress in what you are comfortable in so that you may enjoy the performance. For some, that may mean dressing up in a suit or gown, for others, jeans and a t-shirt is fine. Generally “dressy-casual” is what people wear. Live theater is usually a little more formal than a movie theater.

• At the very beginning of the opera, the concertmaster of the orchestra will ask the oboist to play the note “A.” You will hear all the other musicians in the orchestra tune their instruments to match the oboe’s “A.”

• After all the instruments are tuned, the conductor will arrive. You can applaud to welcome them!

• Feel free to applaud or shout Bravo at the end of an aria or chorus piece if you really liked it. The end of a piece can be identified by a pause in the music. Singers love an appreciative audience!

• It’s OK to laugh when something is funny or gasp at something shocking!

• When translating songs, and poetry in particular, much can be lost due to a change in rhythm, inflection and rhyme of words. For this reason, opera is usually performed in its original language. In order to help audiences enjoy the music and follow every twist and turn of the plot, English supertitles are projected. Even when the opera is in English, there are still supertitles.

• Listen for subtleties in the music. The tempo, volume, and complexity of the music and singing depict the feelings or actions of the characters. Also, notice repeated words or phrases; they are usually significant.

• The singers, orchestra, dancers, and stage crew are all hard at work to create an amazing performance for you! Here’s how you can help them: Lit screens are very distracting to the singers, so please keep your phone out of sight and off until the house lights come up. Due to how distracting electronics can be for performers, taking photos or making audio or video recordings is strictly forbidden.

• The theatre is a shared space, so please be courteous to your neighbors!

? Please do not take off your shoes or put your feet on the seat in front of you.

? Respect your fellow opera lovers by not leaning forward in your seat so as to block the person’s view behind you

? Do not chew gum, eat, or drink, while the rehearsal is in session. Not only can it pull focus from the performance, but many live theaters do not allow food and drink inside the theater..

? If you must visit the restroom during the performance, please exit quickly and quietly.

• Sit back, relax and let the action on stage pull you in. As an audience member, you are essential to the art form of opera—without you, there is no show!