12 minute read

An Artist for All Seasons

(above) Jenny Judge photographed in her studio in August 2020

(right) ”Sandstorm,” molded shapes made of sand, exposed to the elements over time, on Matapouri Beach, New Zealand, 2020

(opposite page) “Whistler Rock Faces,” 2018, each piece 15 cm round, 5 cm depth, kiln cast glass

jennyjudge.com

Jenny TIMBRELL Judge’79 loves to create in every form—and hemisphere

By Janet Sailian

SEB ASTIAN JUDGE Rare and determined is the person who succeeds at a lifelong career in art, and Jenny Judge is one such rarity. Her artistic philosophy incorporates light, shadow, humour and a deep sense of place.

While the contemporary art world oft en expects an artist to have a fi xed, discernible style, Jenny is by nature an explorer. Her diverse creations in metal, glass, ceramics, fi bre, installations, painting and earthworks are linked, she says, by “the magic of investigating and noticing all that is close by.”

“I think of myself as a materialist,” she explains. “I might go off and work in glass for two years, or dive into painting. I always start with materials that can refl ect my purpose.” And those materials sometimes appear through serendipity, prompting spontaneous artistic creation.

When the pandemic erupted, Jenny and her husband Michael were in New Zealand—their second home—and trying to return to Canada. “Th e feeling of isolation, loneliness, and the impact of the worldwide crisis, came crashing together for me when I walked along an empty beach,” says (continued on page 28)

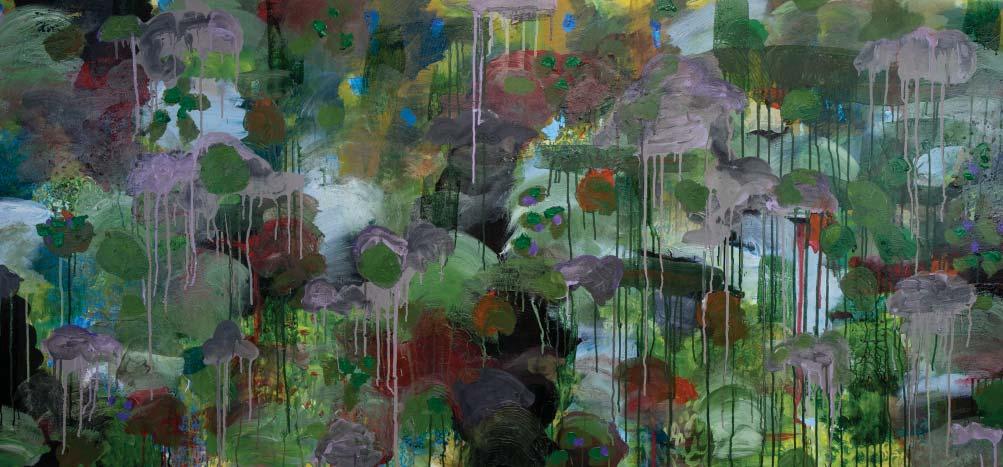

“Forest Floor,” acrylic on canvas, 40" X 75", 2020 (painted in response to the work installed in the forest, opposite page)

(continued from page 27) Jenny. “I sat on the beach and realized how far away Vancouver was.”

Inspired, she created artworks on the shore, using sand and molds from previous work. “Viewers could walk through it and also witness the work being taken away by the tides and wind over a 10-hour period. It was time-based, fl eeting, representing a moment of being present, and then taken away by forces greater than us.” Fortunately, her son Sebastian is a fi lmmaker who documented that ephemeral piece.

Jenny was always a highly visual person who believes that now, more than ever, we need to be visually literate. “Art is both a way of seeing and a way of being,” she says.

Aft er early years at Toronto French School, Jenny arrived at Branksome for Grades 12 and 13, seeking immersion in art. “A new art room had offi cially opened,” she recalls. “It became a place of comfort where I spent time exploring and learning.” Aft er one fi eld trip to the Art Gallery of Ontario, Jenny was assigned to evaluate and analyze an original piece of artwork. “And because I enjoyed the process so much, it helped make my decision to go on to art school.”

She met her husband, Michael Judge,

during undergraduate studies in fine art at Queen’s University (they wed in 1984), and aft er driving across Canada and the U.S. in their Volkswagen van, the couple spent a year backpacking through New Zealand, Australia, India, Nepal and Th ailand. Th ey ended up in Glasgow, Scotland, where both spent a year as visiting artists at Glasgow Print Studios.

Back on this side of the pond, the Judges welcomed children Madeleine, now 29, and Sebastian, 22. Michael’s early career as an internationally competitive windsurfer and sponsored mountain biker ignited the young family’s international travels.

“Living out of the van and travelling the race circuit with the kids and dog were very much a part of our life, especially in the summers,” Jenny says. “Th is is why our children are resilient campers and travellers.”

Meanwhile, Jenny’s art career was taking off . Aft er the young family moved to Vancouver in the early 1990s, she began exhibiting her work throughout the Lower Mainland and in numerous international group shows that took her work (and sometimes her) to France, Scotland, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New

“Moonscape,” 2019, detail, approximately 15 cm, plaster, acrylic paint

LOUISE PARK

“Forest Floor,” detail, 2020; ice, pine needles; one of 80 pieces installed in the forest, Whistler, B.C.

“Pebbly Bay,” detail of a molded shape made from light sand from Matapouri Beach and formed on to Pebbly Bay Beach (a darker sand), New Zealand, 2020

Zealand and the U.S. She also found time to gain a master of fi ne art degree from the University of Minnesota in 1991 and a bachelor of art education from UBC in 1995.

Michael and Jenny both took up teaching. She ran the Sculpture Department at Burnaby North Secondary for five years in the late 1990s. “Th at was such fun,” Jenny says, despite the challenges of parenting two young children, working full-time and putting on exhibitions.

In 2002, the family left for New Zealand to be near Michael’s brother and to explore the new horizons that energize Jenny’s art. Based near Auckland, Michael taught art while Jenny devoted her time to the studio. She learned kiln-cast glass, which launched a 12-year journey in that medium.

Aft er two years they returned to Vancouver, but still felt the pull of New Zealand. “Th at country is a time capsule; it’s like Canada used to be,” Jenny observes. “It’s very communityspirited and kids are freer, less coddled. A subtle diff erence you only perceive by living there.”

So, in 2008, they moved back to New Zealand and became citizens, returning to Canada in 2014 so Jenny could care for her ailing mother, who passed away in 2018. Ever since, the Judges have spent at least three months per year in their Kiwi home.

One of the highlights of Jenny’s career was participating as an artist in the Cheongju International Craft Biennale in South Korea in 2009, where her work was exhibited in the Canadian Pavilion.

“I have also had a lot of fun entering and being involved in ‘wearable art’ events,” she notes. Th e most memorable was at the Corning Museum of Glass in 2016 where all wearables were made of glass, featuring Jenny’s tutu craft ed from illuminated glass spheres.

The pandemic of 2020 has halted all planned exhibitions and lectures for the foreseeable future. “Artists do isolation pretty well,” Jenny says. “I’ve been given this gift of a year just to explore. But if this carries on another year, I will get antsy.”

She sums up: “Everything informs everything. Find your passion, but don’t be afraid to veer away from it and come back.” Anchored by passion and vision, Jenny continues to refl ect on her presence in an ever-changing world through ever-changing art. R

MIDWIFE TO CHANGE

Kelly DOBBIN’89 has always been progressive, whether about women’s health or her own family

By Patricia Hluchy Photo by Jeff Kirk

Kelly Dobbin found her footing as a feminist, and her calling as a midwife, while pursuing women’s studies at McGill. In the early 1990s, there was no option of doing a major program in the fi eld at the university, but “nothing else interested me more,” she recalls. “So I had to fi nally go to the dean of arts and work with them to create this ad hoc degree.” Th e following year, a professor who had helped Kelly assemble her program established a women’s studies major.

Kelly’s coursework led to a discovery of midwifery, the care of women and their babies through early pregnancy, labour and several weeks following delivery. “I didn’t even know that it existed because it wasn’t part of our health system here,” says Kelly, a registered midwife and, since 2013, registrar and CEO of the College of Midwives of Ontario, which ensures that members of the profession are qualifi ed and competent.

“I was interested in health and sexuality and reproduction,” she says, “and once I understood that midwifery was a profession, I tuned right into it. It had all the ingredients for me—working with people, relationship-building—and at the time I was participating in Take Back the

Night marches and delivering talks to fraternities about date rape. Midwifery felt like the logical next step for me since it was about working closely with women and really helping them take back control of their choices and their bodies.”

What followed has been a stellar career of health care and health management. Aft er completing her bachelor’s degree at McGill, Kelly enrolled in the midwifery program Maternidad La Luz in El Paso, Texas—there was no such course in Canada. She then perfected her midwife skills while also working on a master’s in feminist health care at Goddard College in Vermont. In 1994, the year when midwifery became a regulated profession in Ontario, Kelly moved to Guelph, where she went through a two-year process to have her credentials recognized by the Ontario regulator.

Kelly’s approach to midwifery is based on

fostering deep trust in her clients. “Th e midwife knows you, they know what your needs are, what your desires are, and you trust them to create an environment where you can succeed,” she says. “For a midwife going in, I feel you haven’t done your job well if you walk away from that birth and the client says, ‘I couldn’t have done it without you.’ You want them to feel that they did this, they owned the experience.”

In Guelph, Kelly worked on becoming registered and then practised midwifery with Leslie Howarth, who remains a cherished friend. Howarth says Kelly “was a huge support, a motivator and inspiration for me to keep working on obtaining that registration. Kelly never wavered from her advocacy for the rights of her clients to make informed decisions about their care, and she always put in the extra time to ensure the moms and babies were treated with skill and compassion. She is a powerhouse of strength and resilience.

“Maybe the best compliment a midwife ever pays to her sister midwives,” Howarth adds, “is to have them attend their own births. I attended Kelly’s babies’ births and she, two of mine. Th is was where I got to experience fi rsthand her skill and kindness as a practitioner.”

Another close friend, Toronto textile designer Heather SHAW’89, also experienced Kelly’s midwifery skills fi rsthand. “She brought my two boys into the world,” says Heather, who had met Kelly at Branksome. “I was completely swept away by her calmness and by my confi dence in her. Th e thought of handing a headlamp and needle and thread to anyone else I know and letting them go to work stitching me back up is pretty funny to imagine.” Kelly, who relocated to Toronto 20 years ago, has three children with her ex-husband, veterinarian Scott Mathison. Adopted elder son Siphesihle (“Siphe,” pronounced “See-pay), 22, is a fi rst soloist with the National Ballet of Canada; second son Jasper, 20, is studying fi lm and astrophysics at the University of British Columbia; and daughter Ella, 17, is in Grade 12 at Th e York School, where she is the equivalent of head girl. Kelly shares her downtown Toronto house with her children and standard poodles Willow and Violet.

Kelly and Mathison met Siphe in his native South Africa in 2009, having travelled there with Jasper and Ella for a four-month sabbati-

Kelly’s approach to midwifery is based on fostering deep trust in her clients. “The midwife knows you, they know what your needs are, what your desires are, and you trust them to create an environment where you can succeed.”

cal. Th ey enrolled Ella in a dance program and, while attending a community event to which they were invited by her dance teacher, also Siphe’s, they beheld the South African boy onstage. “I just knew he had the potential to be great,” remembers Kelly, who had studied modern dance in her teens and 20s. “He was so in control and so powerful, but at the same time so vulnerable and exposed.”

Siphe was living in the rural township of Zolani, the youngest of fi ve children of a single mother (one of his brothers is also a professional dancer as well as a choreographer, in London). Once Kelly and Mathison learned that Siphe was hungry for more dance classes, they arranged—with the support of his mother, Sylvia, as well as his dance teacher—for him to live weekdays in a nearby community where that would be possible. Th ey also helped him apply to Canada’s National Ballet School (NBS), where he was awarded a full scholarship. Siphe went to live with Kelly and Mathison in Toronto, becoming part of the family, but the couple made sure he visited his South African family twice every year, and they fl ew Sylvia to Toronto for his NBS graduation in 2017. Th ere have been other, extended visits back and forth.

Amid being a mother and bringing Siphe to Canada, Kelly became more interested in policy-making around midwifery. In 2000, she joined the board of the College of Midwives, eventually becoming chair. In 2011 she earned a master’s in public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London, and two years later she took over the helm of the College of Midwives of Ontario. Across the province, midwives now care for approximately 19 per cent of pregnant individuals and their infants (about 27,000 of a total of 142,000 births annually), both in hospital and at home. “My role is just about fostering relationships and creating environments for other people to do well in their careers and make good, solid decisions. It’s a collective effort—we’re all working toward something bigger than ourselves.”

But Kelly’s commitment to society extends beyond feminism and midwifery. She says that movements such as Truth and Reconciliation, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo “have stirred in me the same feelings of injustice that I was so passionately fighting against as a young feminist experiencing gender inequality.” Among the ways Kelly is stretching her progressive self is as a volunteer board member of Toronto’s Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre.

Th at concern about social justice was present in Kelly when she was young, and she says it made her feel somewhat confl icted about attending an elite all-girls school—she was at Branksome from Grades 7 through 10, choosing to go to public school for Grade 11. Still, she cherishes the fact that at Branksome, she “felt really supported and we were allowed to dream big.” Her advice to current Branksome students: “Don’t try to bend yourself to fi t into someone else’s idea of success, but rather, explore what excites you and fi nd a way to bend the world into your plans.” R

Patricia Hluchy is a Toronto freelance writer and editor who has worked for Maclean’s, the Toronto Star and other publications.