HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE PETER & CHRISTINE MOSSE COLLECTION OF RAILROAD ART

Adam Normandin American, b. 1965

Almost There , 2017

Wallace W. Abbey. John Gruber. Stan Kistler. J. Parker Lamb. David Plowden. Jim Shaughnessy. Richard Steinheimer. These titans of American railroad photography are renowned for their powerful images of the transitional era from steam to diesel motive power. Their photographs have formed the foundation of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art since its founding in 1997.

But what about the “Art” in the Center’s name? In 2006 the Center organized an exhibition of railroad watercolors and photographs by the dean of 20th-century American railroad art, Ted Rose (1940–2002), in conjunction with the Ted Rose Studio in Santa Fe. With a collection of close to 30 original watercolors by Rose and works in a variety of media by well-known American artists Howard Fogg (1917–1996), Gil Reid (1918–2007), and others, the Center’s foray into the world of railroad art is more than merely casual; it is part of its core mandate. Railroad art is discussed regularly in the Center’s quarterly journal, Railroad Heritage . Railroad artists such as Gil Bennett, Adam Normandin, J. Craig Thorpe, David Tutwiler, and Roger Watt have made presentations at the Center’s annual Conversations symposia. Still, with rail-related art as pervasive and diverse globally as the tracks and trains that ply the four corners of the world, a broader view was in order.

Enter British-born railroad art collector Peter J. C. Mosse. Mosse connected with the Center during its Ted Rose exhibition in 2006. His passion for and knowledge of railroad art led him to be elected to the Center’s Board of Directors in 2016. In April 2023, Peter and Christine Mosse promised their landmark collection of nearly 250 works of art in all media to the Center. With this gift, the Center will become the custodian and interpreter of one of the finest collections of rail-related art in the United States. Mosse grew up in London in the early 1950s during the nascent days of the nationalized British Railways. When British Railways was formed in 1948, it absorbed over 20,000 steam locomotives from the private railroad companies. Steam trains were everywhere, so it is not surprising that Mosse and young boys of his generation developed an infatuation with trains.

Coupling his passion for trains with an instinct for preservation, Mosse first focused on collecting railroad paper—public and employee timetables—and soon moved on to electro-mechanical railroad signaling equipment when British Rail, as the national rail network was known after 1965, consolidated and modernized its operations, yielding the older technology surplus. With the railroad transitioning to diesel motive power,

thousands of stalwart steam locomotives headed to the scrapyard, which led Mosse to broaden his railroad collection to include number plates, builder’s plates, and, if circumstances were right, highly prized locomotive nameplates.

When Mosse embarked on a career in business and finance and relocated to New York City in 1977, he was forced to sell off much of his collection of signaling instruments and scale down. His subsequent move into railroad art collecting was serendipitous. As Mosse described it:

[My] acquisition of the first painting was, in fact, entirely accidental. One day I saw a railroad painting in a High Street antique shop on Madison Avenue, and eventually plucked up the courage to go in and talk about it. A few days later I decided, “Gosh, I can actually buy that.” I never considered myself to be someone who could buy a painting. It was a very unlikely thing to find in an antiques shop on New York’s

Terence Cuneo

British, 1907–1996

On Early Shift , 1948

Madison Avenue: a beautiful portrait of an Edwardian locomotive of the Great Northern Railway, built in 1904. I learned something very important in this transaction…. I assumed that the person I’d speak to would be a tremendous expert and know absolutely everything about the picture. What I discovered was that while he could speak with tremendous authority about it, most of what he said was in fact total rubbish.

Over the next four decades, Peter and Christine Mosse amassed a diverse collection of rail-related art from all corners of the globe: diverse in historical era, location, artistic style, and subject. Railroad art is not only about depicting hardware and infrastructure; it is also about capturing the people on both sides of the track: railroaders and passengers. Polishing (1984), a large canvas by Zhongli Gong, a Chinese artist who worked in the Xi’an office of China Railways, combines both: a “wiper” in an engine yard cleans the red driving wheel of a Chinese steam locomotive—possibly that of an SL6-Class 4-6-2 Pacific, which was a mainstay of passenger power all over China into the 1980s.

Mosse developed personal relationships with several artists whose works are part of The Art of Trains , and in three instances commissioned paintings from them. One commission is Lostwithiel Crossing Signal Box (1990) by the renowned British railroad artist Terence Cuneo. Mosse’s youthful fascination with mechanical railroad signaling technology led him in the late 1980s to commission a scene that documented this fast-disappearing side of manned railway operations in the face of centralized rail traffic control. Cuneo, who had painted a signalman at work for a popular poster titled On Early Shift published by British Railways in 1948, had not revisited the subject in over four decades, but agreed to accept Mosse’s commission. Mosse describes the give-and-take between patron and artist:

I had told Cuneo at the outset that I would like a modern diesel train to be in the painting, as I was fascinated by the interaction of late 20th-century high-speed trains with late 19th-century signaling technology. Cuneo understood this, but I soon began to sense pushback from him. It would be much nicer, he thought, to see a lowly goods train, with a little steam engine, than an ugly, modern diesel train. Since I felt enormously privileged to be commissioning a painting from such an eminent artist, one who had been an official artist at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, I could only manage to put up token resistance before giving way.

While Mosse wisely recognized that manned trackside train dispatching was vanishing when he commissioned the Cuneo painting in 1990, in fact the Lostwithiel Crossing Signal Box in Cornwall survived well into the 21st century. It was decommissioned in early March 2024 after guiding trains safely along the former Great Western Railway route for 131 years. As Mosse notes, “The Victorians who designed and built it can certainly be proud of their handiwork.”

The impulse to commission a work can be sparked in the most innocuous way. When Mosse was in the MBA program at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in 1970, he saw an image of On Time! , the iconic painting by Griffin Harold “Grif” Teller (1899–1993) commissioned by the Pennsylvania Railroad for its 1932 calendar. The image of the Baldwin-built K4s Pacific 5411 pulling a string of passenger cars through a snowstorm stayed with Mosse—as he puts it, “truly a case of once seen, never forgotten”—and 37 years later he decided to commission a painting that would pay similar tribute to a British steam train. For this commission Mosse turned to Fellow of the Guild of Railway Artists Philip D. Hawkins. Patron and artist worked out the details together:

I had a happy childhood memory of a journey in 1956 from Glasgow to London Euston on The Royal Scot , one of British Railways’ most famous trains. I still have my seat reservation check from that journey and a rather poor photograph I took of the train after its arrival at Euston.

Since my journey took place in August the train reached its destination in daylight, but Hawkins and I agreed that, for dramatic effect, a winter scene would be better. He chose the location, incorporating a signal box and semaphore signals to add interest, but the locomotive portrayed, named City of Bradford , is the one that hauled my train.

The result, Euston, Next Stop (2007), is a powerful image of the heyday of British steam locomotion: BR 46236 City of Bradford (ex-LMS Coronation Class 4-6-2 6236, built at the Crewe Works in 1939) pulls The Royal Scot through the semaphores at Sears Crossing near Ledburn, Buckinghamshire, on its way to London’s Euston Station.

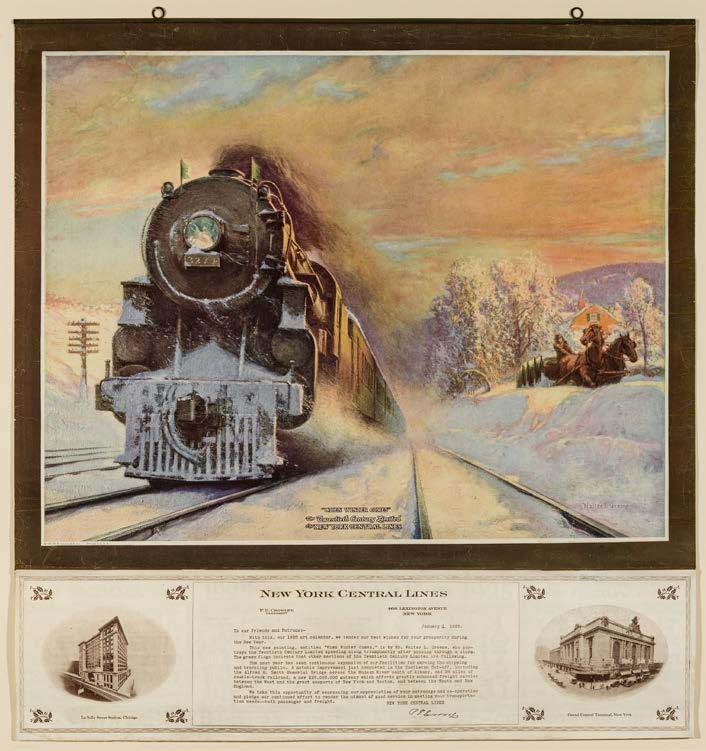

Another “calendar painting” like the Grif Teller that ultimately spawned the Hawkins painting—this one commissioned by the New York Central Railroad for its 1925 issue—is in the Mosse Collection. Indeed, Walter Greene’s When Winter Comes (1925) may have served as inspiration for Teller’s composition from 7 years later. It, too, depicts a “wedge shot” of a steam passenger train plowing through the snow. In this instance, New York Central Class K-3q Pacific 3274 pulls the Twentieth Century Limited on the road’s four-track Water Level Route. The tattered green flags on the locomotive’s head end indicate that this is the flagship train’s First Section, with other sections of the deluxe New York-to-Chicago all-Pullman service following.

Many artists’ names are synonymous with railroading. Teller painted calendars for the Pennsylvania Railroad. Greene and Leslie Ragan (1897–1972) produced memorable paintings for the New York Central Lines that were published as calendars and travel posters. On the West Coast, California Society of Six artist Maurice Logan painted over

Dennis Ziemienski

American, b. 1947

The “Sunset” over the Arroyo, 2008

Maurice Logan

American, 1886–1977

By Rail across Great Salt Lake, Overland Route , 1928

Maurice Logan

American, 1886–1977

By Rail across Great Salt Lake, Overland Route , 1928

20 oils for the Southern Pacific Railway’s California tourism poster campaign. Logan’s first work was a graphic scene of boating on Lake Tahoe in the manner of contemporary German poster design, published in 1923. In the late 1920s–30s, his work for the railroad turned more painterly. At the same time, the Southern Pacific also gave him broader latitude with subject matter, which in 1928 led Logan to the shores of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. There he portrayed the engineering marvel of the Lucin Cutoff, a 102-mile-long railroad shortcut across the terminal lake that opened in 1903 and shortened the original transcontinental Overland Route by 44 miles. Logan’s painting of the Lucin Cutoff, a gull’s eye view of the two-track causeway looking northeast from the western shores of the lake, is a Mosse Collection highlight. Its brushy and brilliant composition is emblematic of the Society of Six’s colorism and technique; however, it was not ultimately used in the

published poster, By Rail Across Great Salt Lake: Overland Route (1928). For the poster Logan alit at the end of the causeway to catch the passing of an eastbound San Francisco Overland Limited and its westbound counterpart. The distant mountains of the Promontory Range grow closer and craggier, but a flock of gulls still soars above.

During his bachelorhood Mosse spent his free time traveling the world to see railroads that had not been modernized and were still operating in traditional fashion, often with steam propulsion. In their retirement, the Mosses continue to lead a peripatetic life, with their travels often revolving around visiting railways, from the tropics of South America to the Intermountain West of the United States. Their trips have also sparked the occasional commission, most notably The Golden Spike (1997), the large, colorful, and charmingly naïve painting by Allan Mardon. The Mosses came across Mardon’s painting of the iconic San Xavier del Bac Mission during a 1995 stay at the Arizona Inn in Tucson. The following year, as Mosse ruminated about the transcontinental railroad’s role in shaping the American West, the idea of commissioning a grand painting of this milestone achievement led him to reach out to Mardon. It was the beginning of a long friendship that only ended with the artist’s death in 2020. Mosse recounts how this commission came about:

[Mardon] had a passionate interest in the history of Native Americans and the idea of a painting that could show the interaction between the railroad and their traditional way of life greatly appealed to him. We agreed that the centerpiece of the work should be the Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory Point, but beyond that I had little idea as to how the painting might be composed.

Allan Mardon

Canadian, 1931–2020

San Xavier del Bac, 1990

Gerard Fortune

Haitian, 1925–2019

S ugar Cane Train, c. 1970s

I have always believed that if you need to micromanage an artist to whom you’ve given a commission, then you’ve chosen the wrong artist. Mardon, a Canadian who had trained in Toronto, Edinburgh, and London, had not painted a railroad subject before, so I supplied him with references and source material, and he drove to Promontory Point in Golden Spike National Historical Park to see the exhibits there and speak to Park Service personnel. Early on he faxed me a preliminary sketch, just enough for me to understand the composition he had in mind, and it was well beyond anything I could have thought of.

The commission took 18 months to complete and was well worth waiting for. I made it very clear from the outset that I did not want him to paint under pressure, I only wanted him to paint when he felt the moment was right. And almost immediately after the painting arrived in New York, I sent it off to the Brinton Museum in Big Horn, Wyoming, to be included in an exhibition of Mardon’s work, where it turned out to be the star of the show.

The Mosses’ transformative promised gift of their extraordinary railroad art collection to the Center for Railroad Photography & Art will go far in raising the stature of the art of trains among railroad lovers, historians, and curators. Thanks to their generosity, Terence Cuneo, Philip D. Hawkins, Maurice Logan, Walter Greene, and scores of other artists will assume their places among the academy of men and women who are lured trackside to witness and record the power, majesty, and continuing relevance of the railroad.

ERIC BAUMGARTNER

Hirschl & Adler Galleries

Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait

British American, 1819–1905

Dutton Viaduct over the River Weaver, 1849

David Halbach

American, 1931–2022

Track Inspectors , 2003

John Austin

British, b. 1949

Venus at Dillicar, 1971

Lee Alban

American, b. 1948

Goggles , 2015

Cecil Crosley Bell

American, 1886–1977

West Side Cowboy , before 1941

Peter Insole

British, b. 1957

Green and Gold to Golders Green , 2006

Lorusso

American, b. 1966

A Last Goodbye , 2004

Philip Reisman American, 1904–1992

Waiting Local , 1979

1

Lee Alban

American, b. 1948

Goggles , 2015

Oil on panel, 24 x 18 in.

2

John Austin

British, b. 1949

Venus at Dillica r, 1971

Oil on canvas, 24 1⁄ 2 x 34 in.

3

Cecil Crosley Bell

American, 1906–1970

West Side Cowboy , before 1941

Oil on Masonite, 22 x 30 in.

4

Karen Clarkson

Choctaw, b. 1951

Choctaw Railroad Certificate (The Choctaw Route), from the series

A Choctaw Story of Land and Blood , c. 2017

Watercolor and gouache on enlarged print of a stock certificate, 11 x 17 in. (sheet)

5

Terence Cuneo

British, 1907–1996

Lostwithiel Crossing Signal Box , 1990 Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in.

Roger Watt

British Canadian, b. 1947

Times Square , 2013

6

Arthur Filon

French, 1900–1974

Le Canal Saint-Martin et le petit train , c. 1930s Oil on canvas, 17 1⁄ 2 x 21 in.

7

Gerard Fortune

Haitian, 1925–2019

Sugar Cane Train , c. 1970s Oil on plywood, 23 1⁄ 2 x 23 1⁄ 2 in.

8

Zhongli Gong

Chinese, active 1981–84

Polishing , 1984 Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 in.

9

Walter Greene

American, 1870–1956

When Winter Comes , 1925 Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in.

10

Walter Greene

American, 1870–1956

Wall Calendar for New York Central , 1925 Color lithoprint on card stock, 30 1 ⁄ 4 x 28 3 ⁄ 4 in., with frame

11

David Halbach

American, 1931–2022

Track Inspectors , 2003 Watercolor on paper, 21 x 29 in.

12

Philip D. Hawkin s British, b. 1947

Euston, Next Stop , 2007 Oil on canvas, 20 x 25 in.

13

Peter Insole

British, b. 1957

Green and Gold to Golders Green , 2006

Gouache and crayon on paper, 13 1⁄ 2 x 17 1⁄ 2 in.

14

Maurice Logan

American, 1886–1977

By Rail across Great Salt Lake, Overland Route , 1928 Oil on panel, 22 1⁄ 2 x 17 1⁄ 2 in.

15

Joseph Lorusso

American, b. 1966

A Last Goodbye , 2004 Oil on board, 24 x 30 in.

16

Allan Mardon

Canadian, 1931–2020

The Golden Spike , 1997 Oil on canvas, 45 1⁄ 2 x 72 5 ⁄ 8 in., including artist-painted frame

17

Adam Normandin

American, b. 1965

Almost There , 2017

Oil and acrylic on linen, 60 x 40 in.

18

Gregorio Prestopino

American, 1907–1984

The Bridge , 1947 Oil on board, 18 x 26 in.

19

Philip Reisman

American, 1904–1992

Waiting Local , 1979 Oil on canvas, 20 x 40 in.

20

Valery Sekret

Russian, b. 1950

Train Station , 2007

Oil on canvas, 18 1 ⁄ 4 x 22 1⁄ 2 in.

21

Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait

British American, 1819–1905

Dutton Viaduct over the River Weaver, 1849

Oil on canvas, 24 x 34 in.

22

Roger Watt

British Canadian, b. 1947

Times Square , 2013

Graphite on paper, 10 1⁄ 2 x 16 1⁄ 2 in.

23

Dennis Ziemienski

American, b. 1947

The “Sunset” over the Arroyo , 2008 Oil on canvas, 34 3 ⁄ 4 x 411 ⁄ 4 in.

Walter Greene

American, 1870–1956

Wall Calendar for New York Central , 1925

design

Elizabeth Finger Design

photography

All photographs by Eric W. Baumgartner, except margin photographs on pp. 5, 6, 11, and 14

cover

Zhongli Gong

Chinese, active 1981–84

Polishing , 1984

Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 in

inside front cover

Valery Sekret

Russian, b. 1950

Train Station , 2007

Oil on canvas, 18 1 ⁄ 4 x 22 1⁄ 2

frontis

Gregorio Prestopino

American, 1907–1984

The Bridge , 1947

Oil on board, 18 x 26 in .

H&A