American Essence

Double Trouble

Twins from around the country descend upon the small town of Twinsburg, Ohio, every year

The Other Night Rider

The little-known Virginian from history who warned patriots that the British were coming

Double Trouble

Twins from around the country descend upon the small town of Twinsburg, Ohio, every year

The Other Night Rider

The little-known Virginian from history who warned patriots that the British were coming

Eric Weddle, whose surprise return for the LA Rams at this year’s Super Bowl shocked the sports world, exemplifies humility on and off the field

It all comes down to values.

HPU is a God, family and country school. ,, ,,

DAVID AND LISA AMIGO (PARENTS OF THREE HPU STUDENTS)

Discerning Parents can remove the fear and stress of the college search process by downloading the FREE FAMILY GUIDES to choosing the right college. Available in print or digital versions, the following guides will help you uncover red flags and discover hidden gems. Get Instant Access to these College Guides:

The Ultimate College Tour Checklist: Ask these 20 questions on every college tour to reveal crucial insights beyond the tour guide’s talking points.

Learning Beyond Lecture Halls: How experiential learning propels students to discover and achieve their career goals.

The Parents’ Guide to Values-Based Living and Learning at College: Perspectives from real parents on the critical, character-based educational elements that typical college rankings can’t measure.

Understanding What Employers Really Want: How Premier Life Skills prepare students for success.

The National C-Suite Survey on College Graduates in the Workforce: Insightful data that reveals why some employees get hired and promoted while others are simply overlooked or fired.

Download for free at www.highpoint.edu/family-guides

The Upper and Middle Falls of the Genesee River, as seen from Letchworth State Park, N.Y.

“The best way to predict your future is to create it.”

The only producer & maker of elderberry extract in convenient single-serve packets for longer shelf life. No refrigeration needed.

Produced in its purest liquid form for better absorption and higher efficacy than pills or powder, Elderberry Ultimate has a high ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity) value for combating free radicals in your body and is filled with rich antioxidants including anthocyanins, vitamin A, potassium, vitamin C, folate, calcium, and iron. Packets can be mixed with water or into your favorite drink.

Made in small batches by hand in Denmark, Wisconsin, Elderberry Ultimate is infused with elderflowers, one of nature’s highest sources of quercetin, a powerful flavonoid.

An instant hit since its debut in 1964, the all-American Mustang has distinctive features that have with stood the test of time and defined it as an icon.

12 | A Triumphant Return Football star Eric Weddle fully embraced the life of a stay-at-home dad until fate called upon him to deliver an epic comeback.

18 | Beginning to Mend

A grieving father and a book author are serendipitously brought together, neither one expecting that playing catch could bring so much healing and solace.

Have you seen these candies? Be on the lookout for these nostalgic sweets from different states across America.

Meet an Arizona father-and-daugh ter duo on a mission to revive the forgotten tradition of stone mill ing and save nutrient-rich heritage grains from extinction.

36 | Truffle Treasure Hunt

Venture deep into the forests of Oregon with the Czarnecki family to uncover wild treasures that rival their European counterparts.

40 | Of Love and Letters

Writer Andrew Benson Brown recounts the sweet courtship between his grandmother and grand father, a war hero with a strong work ethic and rock-solid principles.

42 | Why I Love America Jade Gillespie reflects on how our nation—a land of limitless possibil ities—is sustained by generations of steadfast Americans who dare to dream.

44 | Generations of Generosity

Going from a poor immigrant to a renowned financier, Henry Villard inspired a legacy of courage and kindness that is well remembered by his great-granddaughter.

50 | Twin Glory

A photo essay on the annual festival in Twinsburg, Ohio, that celebrates the bond between twins.

60 | The Other Night Rider

Having overheard British plans for an ambush, Virginia farmer Jack Jouett dashed a daring 40 miles to save Thomas Jefferson and other patriots from capture.

It was Dolley Madison’s quick wit during the War of 1812 that saved one especially precious White House treasure from doom.

68 | The Spirit of Texas Brave and fiercely loyal, Gen. Sam Houston led his men to a pivotal victory in the Texas Revolution and later became the first governor to serve two states.

From educating unruly children to nursing wounded Civil War sol diers, the selfless founder of the American Red Cross brought com fort to everyone she encountered.

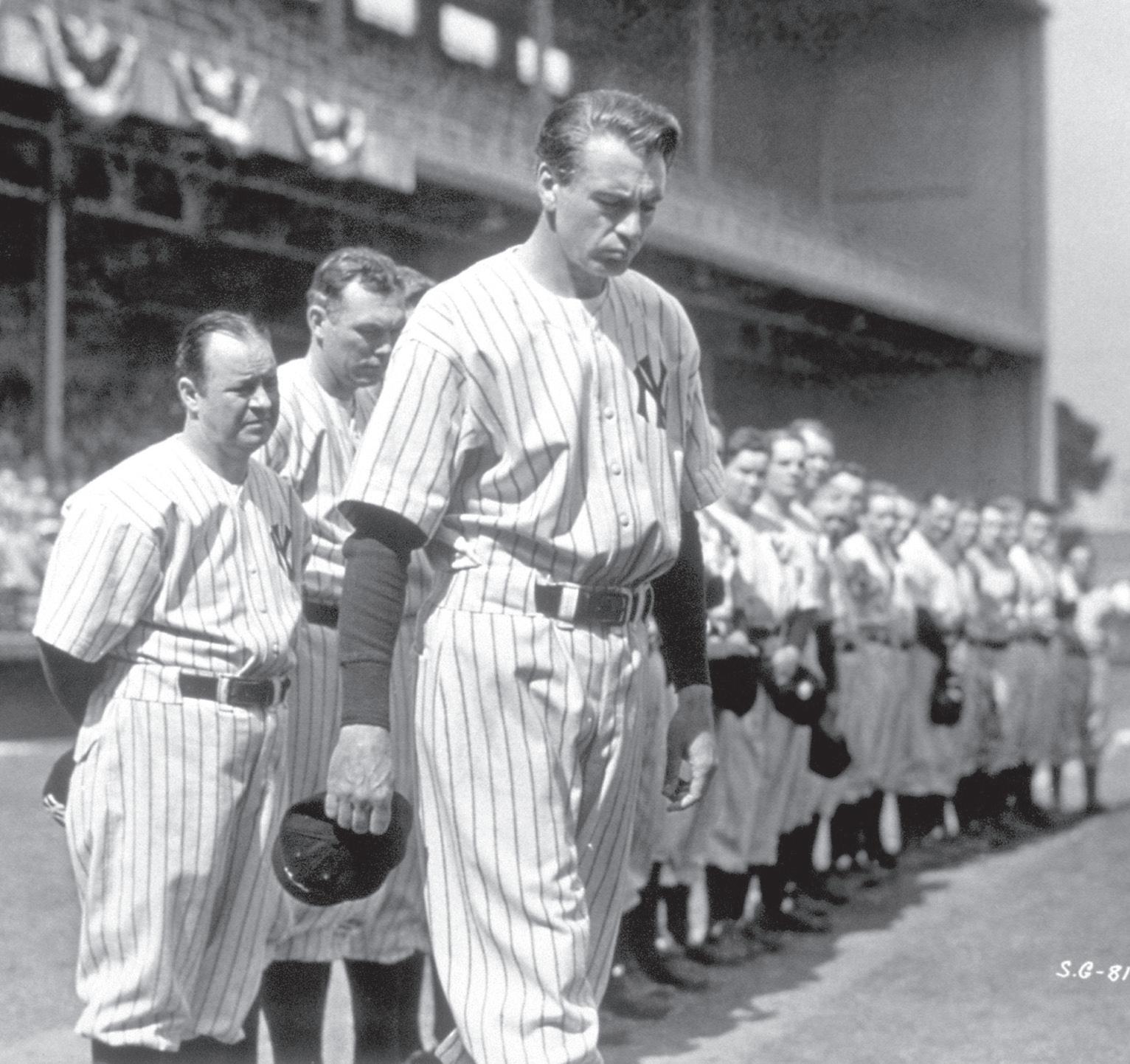

Few men live up to their legends. This one did: First baseman Lou Gehrig inspired a nation during one of its toughest times.

The president’s home away from home can accommodate every need, from serving luxurious meals to handling emergency surgeries.

88 | Book Recommender

Your next great reads: A thrilling murder mystery involving fascism and anti-fascism too close to home; and an engaging bestseller explor ing how faith laid the foundation for the American republic.

90 | The Makings of a Hero

A look at the epic adventure novel “The Last of the Mohicans” and its lasting impact on American literature.

96 | House of Ideals Journey through the past to Montpelier, the idyllic plantation home of James Madison, where the early ideas of our Constitution were born.

104 | Music Speaks

Grammy Award-winning fiddler Eileen Ivers on embracing her IrishAmerican roots and bringing people closer together through music.

Rugged Ringwear is dedicated to creating one of a kind, high quality rings that are handcrafted just for you.

Our mountain collection features a variety of styles. Choose a specific mountain range or let us free-hand carve one for you!

Sports keep us on the edge of our seats. The drama and heroism on the field often have no match elsewhere.

For our main feature, we inter viewed former NFL player Eric Weddle (page 12), who had been retired for two years—with plenty of achievements under his belt, includ ing being a two-time All-Pro player—when the call came, three weeks before this year’s Super Bowl: The LA Rams needed him back. He said yes, and the rest—despite naysayers’ expectations—is history.

You’ll also find a story about baseball leg end Lou Gehrig (page 76). He hit a legendary streak as Americans were struggling through the Great Depression, a time when the coun try sorely needed inspiration—and a hero. Yet through it all, he remained remarkably hum ble.

Finally, for a lighthearted touch, see our photo essay of this year’s annual Twins Day Festival in Twinsburg, Ohio (page 50), where a spirit of joy reigned in full glory. It’s a tribute to the sometimes quirky nature of American festivals, but above all, to family ties.

Channaly Philipp

Annie Wu

Sharon Kilarski

Jennifer Schneider

Crystal Shi

Tynan Beatty Maria Han

Jennifer Tseng Jasmina Zhang

Dariya Akdeniz

Michael Kurov

Sunny Ho Amy Han

Tatsiana Moon

Sandy Lindsey, Andrew Benson Brown, Alice Giordano, David Dudley, Kevin Revolinski, Deena C. Bouknight, Jill Dutton, Jade Gillespie, Jeff Minick, Debi DeSilver, Rachel Pfeiffer, Dustin Bass, Pamela Beiler, Mark Lardas, Bob Kirchman, Lorraine Ferrier

American Essence (USPS 24810) is published monthly by Bright Magazine Group at 5 Penn Plz. Fl.8, New York, NY 10001. Periodicals postage is paid at New York, NY.

Postmaster: Send address changes to American Essence, 5 Penn Plz. Fl.8, New York, NY 10001. General Inquiries: AmericanEssence.net/help

Set with exquisite diamonds on one side and the birthstones of family members on the side worn closest to the heart. This unique treasure is one that will instantly become a precious heirloom.

Arlington Centre Blvd., Suite 130 Columbus, Ohio 43220

The football star, who helped lead the Rams to Super Bowl victory this year, coaches high school football, teaches Sunday school, and can still make a mean PB&J sandwich WRITTEN BY Alice Giordano PHOTOGRAPHED BY Heather Broomhall Photography

It was called everything from a male ver sion of a Cinderella story to the greatest comeback in American sports history. It drew even those who are most uninter ested in football to their television sets. Some football fanatics even couldn’t believe what they heard.

Just three weeks before Super Bowl LVI took place in February 2022, ex-NFL safety Eric Weddle got a phone call that sounded more like the neighborhood kids asking him to come out and play. And to some extent, it was.

Only it was the Los Angeles Rams, a little stunned themselves by their underdog status as an unlikely contender in the playoffs for the highly coveted Super Bowl. The California team found itself unexpectedly without either of its safeties, and so it turned to a former teammate, who had retired two years earlier after a 13-year-long career in the NFL.

“The first question they asked me, is what kind of shape I was in,” recalled Weddle. He admits he is still pinching himself, several months after helping to lead the Rams to vic tory.

The surprise invitation would create the ultimate in second chances and also turn Weddle into an even bigger role model off the field.

Weddle, remembered mostly for his days with the Baltimore Ravens and San Diego Chargers, retired after the 2019 season with the LA Rams without a Super Bowl win—a reality that was tough for him, he said, but some thing he just had to accept.

The six-time Pro Bowler and two-time All-Pro player thus settled into life as a fulltime dad. Weddle soon became busy making school lunches and driving around his son and three daughters to their litany of activi ties: Brooklyn, the eldest, plays volleyball and

soccer; Gaige, obviously football; Kamri is involved in acrobatic dance; and then there’s Silver, whom Weddle affectionately calls “our baby monster” because she’s into everything!

Then came the phone call. After Weddle’s return was announced to the press, Rams coach Sean McVay expressed this laudatory sentiment: “If there was anybody that was going to be able to do it, it would be him.” Not only did 37-year-old Weddle suit up, but his performance was bar none, completing five tackles—with a ruptured pec to boot—in what turned out to be one extra-glorious win against the Cincinnati Bengals. His tackle of Bengals wide receiver Tyler Boyd during the team’s final drive deprived it of one more chance to add points to the scoreboard, leav ing the Rams’ lead of 23–20 as the final score at the Super Bowl.

Weddle was the talk of the town with his storybook comeback, headlining ESPN, CBS Sports, and every other media outlet in between.

vvv

“Every football team has a great locker room. ... Race, political views, where you’re from—that all doesn’t matter, because we’re there as a team with one common goal: to win.”Super Bowl champion Eric Weddle with his wife, Chanel, and four children: his son, Gaige, and daughters Kamri (back row), Brooklyn (seated right), and Silver (seated left), photographed in Poway, Calif.

A ball-hawking safety who led the league in interceptions and was recently placed on the 2023 ballot for College Football Hall of Fame for his early days with the Utah Utes, Weddle was back in the game, and the NFL wanted him. Who wouldn’t cave to such temptation?

But to Weddle, the choice was clear. This fall, Weddle hit the field as head coach of the Broncos—that is, the Rancho Bernardo High

School Broncos in San Diego, a homespun venue far removed from the million dollar NFL clubhouses that Weddle is so well-ac quainted with. It’s also where his 14-year-old son is now attending school.

“I had every opportunity, but in my mind, if I’m going to be involved in football, coach anyone, why not it be with my own son,” reflected Weddle—who, by the way, also loves to cook. “This is an opportunity for me too, to be a leader in a different way to my kids and

ABOVE RIGHT Weddle previously played for the San Diego Chargers. Here, he’s in a game against the Buffalo Bills.

RIGHT Weddle with his family after the Los Angeles Rams won the Super Bowl.

the other kids.”

Leadership, he said, sometimes means not being afraid to go against the mainstream. And he sees football, as well as other sports, as an unsung teacher of leadership—both on and off the field. “You learn so much from sports, how to treat people, how to interact, how to work through problem solving, how to communicate, how to handle adversity, and competing,” he said. “You’re also trying to beat other people at a play. Sometimes it works in your favor and sometimes it doesn’t. Are you going to quit, or are you going to keep fighting and keep pushing?”

And if you’re not hooked on football yet, consider Weddle’s viewpoint on how it could mend the world through example. “Every football team has a great locker room,” he

Hometown:

Alta Loma, California

Position:

Free safety College: University of Utah

Career history:

San Diego Chargers, 2007 to 2015

Baltimore Ravens, 2016 to 2018

• Los Angeles Rams, 2019 and 2021

Total tackles: 1,179

Defensive touchdowns: 5 Forced fumbles: 8

Interceptions: 29

A tour of retro candy across the country

A candy maker opened a factory in Tacoma, Washington in 1911, but he couldn’t compete with another local manufacturer. So he tried again in 1920, back in his home state of Minnesota, and found success with an idea his son gave him to make a candy bar based on a popular style of milkshake: the Milky Way. Frank C. Mars’s local product went viral, you might say, and now his creations are part of a large international corporation. But many are the sweets that, though popular for generations, remain associated with their home turf.

WRITTEN BY Kevin Revolinski ILLUSTRATED BY R.W.First sold in 1918, Cherry Mash is still produced in Missouri and not typically found outside the Midwest. The recipe calls for a fluffy center of fondant whipped with mashed maraschino cherries, and a chocolate coating studded with bits of roasted peanuts.

Arizona

Fruit might not be the first thing that comes to mind when you hear Arizona, but then there is the prickly pear. From 1942, Cactus Candy used the juice of this des ert fruit to cook up sweet, sugar-coated jellies. Another company bought the rights in 1996, but the candy is still made and sold in cactus country.

A staple since 1912, Goo Goo Clusters have become legendary beyond their home in Nashville. Visitors to the city should be sure to pick up these chocolate-covered clusters of nuts, caramel, and nougat before they pack for home.

A door-to-door candy salesman hooked up with a local family in Boise to build the Idaho Candy Co. candy factory in 1909. First pro duced in 1918, the Idaho Spud—a potato-shaped confection with a chocolate coating and coconut sprinkles around a cocoa-flavored marshmallow center—is still their most popular product.

Illinois

This is an unusual one, as everything in the name is wrong: They are not beans, nor are they baked, and nor do they hail from Boston. They do, however, resem ble the beans that gave “Beantown” its nickname. These candy-coated peanuts were first created in Chicago in 1924 by Salvatore Ferrara, and the company that bears his name still makes them.

First manufactured in 1922 by Colby & McDermott in Los Angeles, this flat bar is made of white taffy wrapped around a peanut but ter filling. Hayward, California-based Annabelle Candy Company bought the brand in 1978, and while it does cross state lines, you won’t likely find it east of the Rockies.

Texas

Salty, sweet, and crunchy, these candy sticks made with toasted coconut and peanut butter were originally called Chicken Bones when Atkinson Candy brought them to market in 1938 in Lufkin, Texas (note the Lone Star in the Atkinson logo).

Blue Monday Kentucky Ruth Hunt started out making sweets for friends and family in 1921, but success led her to build a factory in 1930. A bittersweet dark chocolate-covered candy cream would emerge as a favorite. The story goes that a minister stopped in for the sweet treats on Mondays to cure his Monday blues—thus the name!

Wisconsin

In a state full of dairy cattle, everyone knew what a “cow pie” was. But in 1981, Baraboo Candy Co. gave a new—and more palat able—meaning to the term. The Original Cow Pies are delicious caramel and pecan patties cov ered with chocolate.

New Jersey

Salt water taffy came to be in the 1880s along the boardwalk in Atlantic City, allegedly after stormy sea spray salted a vendor’s taffy supply. Two vendors would go on to make big names for themselves: Fralinger’s and James’, which survive today.

Emma Zimmerman, co-founder of Hayden Flour Mills, mainly handles the business side of the company, but she still makes time to check on the wheat fields and talk with the farmers— sometimes with her family in tow.

A father-daughter team set out to resurrect the legacy of a 148-year-old Arizona flour mill—and save even older heritage and ancient grains from extinction

WRITTEN BY Deena C. Bouknighty dad and I have one rule: He’s only allowed to tell me one new idea a day”—so Emma Zimmerman begins her book, “The Miller’s Daughter.” Yet it was one of Jeff Zimmerman’s “wild ideas” in 2009 that halted Emma’s doctoral path in neuro ethics and set her on the road to what she now calls her dream job: saving near-forgotten heritage and ancient grains from extinction.

At Hayden Flour Mills in Queen Creek, Arizona, the Zimmermans and their team grow and freshly mill storied grains with names like White Sonora wheat, emmer farro, Tibetan purple barley, and Blue Beard durum, and ship them to customers across the coun try.

“The flavor and color of these grains is the best part,” said Emma. “The grains we grow are all so unique in their aroma; I could prob ably tell which grain is which by just smelling them.” Whether it’s “light and creamy” White Sonora, “full-bodied” einkorn with its “gen tle herbiness and undertones of vanilla,” or “black coffee”-like gazelle rye with “a heady sage and floral aroma,” these are nuances you won’t find in a supermarket bag of industrial white flour.

But in a modern world desiring familiar, fast, and cheap, making these old, obscure grains commercially viable is no small feat. They spent years researching and learning, often by trial and error, every step of the process.

Instead of a dissertation, Emma ended up

writing a cookbook (“An equally big under taking,” she said) about why these grains matter—and, of course, how to cook and bake with them.

Raised on a North Dakota farm, Jeff Zimmerman, like many farmers in the latter 20th century, witnessed the industrialization of wheat farming. He watched the wheat on his family farm diminish in height and qual ity with the introduction of new seed variet ies during the Green Revolution of the 1960s, bred for higher yield and faster profits—at the

vvv

QUINCES ARE KNOBBLY POME FRUITS with the texture of an apple and the scent of a guava. The combination of quince, rye flour, and honey is a match made in heaven, as this luscious recipe amply demonstrates. The batter rises up over the fruit to create a fun “sunken” effect that makes this simple tea cake feel fancier than it really is. If quinces are hard to find or out of season, baking apples make a great substitute.

Serves 8

• 3 quinces

• Juice of 1 lemon

• 2 tablespoons granulated sugar

• 10 tablespoons (5 1/2 ounces/150 grams) unsalted butter, at room temperature

• 1/4 cup (3 ounces/85 grams) honey

• 1/2 cup (3 1/2 ounces/100 grams) granulated sugar

• 3 eggs

• 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

• Grated zest of 1 lemon

• 1 1/4 cups (6 ounces/175 grams) rye flour

• 2 teaspoons baking powder

• 1/4 teaspoon fine sea salt

• 3 1/2 fluid ounces (100 milliliters) whole (full cream) milk

• Powdered (icing) sugar, to serve

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Butter a 9-inch springform cake pan.

Peel the quinces, taking care as some variet ies can be very hard, and cut them into halves. Use a tablespoon to scoop out the seeds and tough interior. Score the outside of each piece in 1/4-inch-thick slices, being careful not to cut all the way through. As the quince bakes, it will fan apart and the scoring will help to soften the fruit. Toss the prepared quince in the lemon juice and sugar and set aside.

For the batter, in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream together the butter, honey, and sugar, then add the eggs, one at a time, and beat on high speed until fluffy. Add the vanilla and lemon zest.

Combine the flour, baking powder, and salt in a separate bowl, then gradually add to the butter mixture, mixing gently on the lowest speed until incorporated. Mix in the milk.

Pour the batter into the prepared pan and smooth the surface. Arrange the scored quince halves on top, scored side up (if there is room, place the sixth piece in the middle of the cake). There’s no need to press them into the batter as the cake will rise around them in the oven.

Bake for 40 minutes until the top of the cake is golden and the quince pieces are soft. Allow the cake to cool completely in the pan, then sift powdered sugar over the top and serve. The cake is best eaten on the day of baking, but left overs will keep in an airtight container at room temperature for up to 3 days.

The great-granddaughter of Henry Villard, the famed 19th-century financier who built the Northern Pacific Railroad and masterminded the creation of GE, honors his legacy

WRITTEN BY Alice Giordano

WRITTEN BY Alice Giordano

LEFT Henry Villard was a man of grit and determination.

Portrait taken circa 1881.

ABOVE Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave is dedicated to carrying forward the legacy of her great-grandfather, who emigrated from Germany to America at the age of 18.

Her name alone is nearly poetic, but it is history and grandeur that give Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave her befitting nomenclature.

She is the great-granddaughter of Henry Villard, a Bavarian native who came to America with only 20 borrowed dollars in his pocket—only to make groundbreaking finan cial ventures and become president of the Northern Pacific Railroad and owner of the New York Evening Post. He also built what has become one of Manhattan’s most recog nizable architectural landmarks: the Villard Houses, a Gilded Age mansion that today houses the luxurious Lotte New York Palace hotel.

He believed so much in the greatness of America that he put his whole soul into the railway company—allowing it to complete the country’s second transcontinental railroad— and funded Thomas Edison’s early exper iments in electricity, Alexandra reflected.

Meanwhile, the Villard Houses remain one of the few surviving examples of stunning design by the acclaimed architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White.

Villard immigrated to the United States in 1853 from Germany at the age of 18. Within five years of arriving in America, he mastered the English language and began working for leading daily newspapers at the time. Villard covered the famous presidential debates between Abraham Lincoln and Democratic Illinois senator Stephen Douglas over the issue of slavery. Lincoln took a shine to him, and included him in his entourage. Villard was the only correspondent, then working for the Associated Press, to accompany the president-elect on his inaugural train from Springfield, Illinois to the nation’s capital. Then, during the Civil War, he was a war cor respondent for The New York Herald and later for the New-York Tribune. In his cover age, he made sure black soldiers were prop erly commemorated for their service.

He was there when Thomas Edison famously lit up the first incandescent light bulb at Menlo Park, New Jersey in 1879. Villard would later hire Edison to install lighting aboard his new steamship, the S.S. Columbia. That was the first commercial installation of Edison’s invented light bulb. The installation was successful as the ship made its trip around South America. “Of all of my patrons,” Edison said, “Henry Villard believed in the light with all his heart.”

In 1881, Villard secured control of the Northern Pacific Railroad company through what modern-day finance would call a lev

vvv Villard built his wealth from the ground up and was generous with it, paying off debts for universities and financing some of America’s most iconic architectural preserves.

An Ohio festival celebrates the special bond between twins

At the world’s largest gathering of twins, there’s a surreal feeling upon laying eyes on so many sim ilar faces in the same place at the same time—akin to being dropped into a par allel dimension. The Twins Days Festival has been held in Twinsburg, Ohio, annually since 1976. An atmosphere of whimsy and joy per

meates the gathering. With this year’s theme being “welcome to the jungle” (past themes include fairy tales, outer space, Westerns, and Noah’s Ark), parade participants and spec tators alike dressed in safari outfits, animal prints, and other vibrant costumes. Fun con tests are held to determine the most alike and least alike in different age groups.

The Yankee baseball player was a titan on the field, humble as a man, and beloved by millions during a time when America most needed heroes

WRITTEN BY Dustin BassLou Gehrig in his first appearance with the New York Yankees during a game on June 11, 1923.

Earle F. Zeigler, a founder of the North American Society of Sport Management, once wrote that “from antiquity we know that ‘hero’ was the name given to a man of ‘superhuman strength, courage, or ability, favoured by the gods; regarded later as demigod and immor tal.’” He further defined a cultural hero as “a mythicized historical figure who embodies the aspirations or ideals of a society.” In his essay “Babe Ruth or Lou Gehrig: A United States Dilemma,” Zeigler concluded that if America did have a cultural hero, it was not Babe Ruth, but rather Lou Gehrig.

In late June 1939, America was dumbfounded at the news that Lou Gehrig—baseball’s Iron Horse—was retiring. The New York Yankees announced that July 4 would be “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day.” Gehrig had become a national icon, a hero. The Fourth of July is meant for celebrating national heroes, but this year it was a day of mourning. Gehrig was not simply retiring; he was dying.

Gehrig stood at home plate. His feet close together at the corner of the chalked box, his doffed cap tucked under his right arm. His eyes focused on the ground, only poking his head up every so often to glance at the speaker or receive a gift. For the previous 16 years, Gehrig had made home plate his home. It was where his strength captivated audi ences. Now, they were captivated by the trag edy that his strength had vanished.

In so many ways, Gehrig had become that mythicized figure. He was blessed with superhuman ability, power, and endurance. He demonstrated that fact by crushing 493 home runs. He played in 2,130 consecutive games, a feat unthinkable and a record that

seemed unbreakable. His threshold for pain was otherworldly. Gehrig had won two Most Valuable Player awards, a Triple Crown, and was a seven-time All Star (the first All Star Game for Major League Baseball was in 1933). He led the Yankees to seven World Series, of which they won six. He batted clean up on the most feared offense in MLB history—the 1927 lineup known as Murderers’ Row. He had 13 straight seasons of at least 100 runs batted in (RBIs) and 100 runs scored. He set the still-standing single-season American League record for RBIs with 185. Gehrig was the Yankees’ all-time hits leader, and he would remain so for 70 years. His gift was baseball, but now that gift was gone—rescinded, as if the baseball gods had cursed him for achiev ing such divine status.

Gehrig was born on June 19, 1903, to German immigrant parents, Heinrich and Christina. He was strong, approximately 14 pounds—as if born for athletics. He was the Gehrigs’ only surviving child. None of their other three children would reach the age of two. They were a close family, with an exceptionally strong mother-and-son bond.

His father struggled to hold down a job, which placed much of the responsibility on his mother to make ends meet. She worked tirelessly as a maid, and she constantly

Gehrig had won two Most Valuable Player awards, a Triple Crown, and was a seven-time All Star.

encouraged Gehrig to pursue his studies. He graduated high school and attended Columbia University in hopes of becoming an engineer (more his mother’s wish than his). But grow ing up in Manhattan near the Polo Grounds— home of the New York Giants—baseball was his first love.

He was a star in high school. That star shone brightest before a crowd of 10,000-plus spectators at the 1920 Chicago-sponsored intercity game between Manhattan’s High

School of Commerce and Chicago’s Lane Tech High School. His soaring grand slam in the ninth inning led the New York Daily News to call him “Babe Gehrig.” The moniker was not hyperbole. He would soon be consid ered “the Babe Ruth of the colleges.” Three years later, while Gehrig was playing base ball for Columbia University, Paul Krichell, the Yankees scout, swore he had found the “second Babe Ruth.” His discovery was welltimed, perhaps destined. Gehrig’s mother

ABOVE American actor Gary Cooper re-enacts Gehrig’s farewell speech (July 4, 1939) in the 1942 film “The Pride of the Yankees.”

FAR RIGHT New York Yankees players (L to R) Babe Ruth, Bob Shawkey, and Gehrig sit on a batting practice backstop at Comiskey Park in Chicago, 1930.

had come down with pneumonia, and with little money, the outlook was dim. Krichell offered Gehrig a contract for the six months remaining in the season of $400 a month and a $1,500 signing bonus. Gehrig signed, and his mother was able to get the treatment she needed.

“I’ll never forget the night I went home and told my mother that I was going to quit college and go into baseball,” Gehrig wrote in 1927. “She broke down and cried when I told her. She insisted that I should stay on in school.”

Despite his mother’s insistence, baseball and the legendry of the Yankees was calling.

The first and actual Babe Ruth entered the major leagues in 1914, less than a month before the outbreak of war in Europe. He came in as a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. When the war ended, so did his days in Boston. He would become a Yankee, but no pitcher. He would become the Sultan of Swat, the Great Bambino, The Babe. The year Gehrig hit his high school grand slam, Ruth was on pace for an unprecedented 54 home runs.

Just like every other kid who loved baseball, Gehrig idolized Ruth. To be signed with the Yankees and to play next to Ruth was unfath omable. To be considered The Babe’s second coming seemed almost blasphemous.

After two seasons in the minors, Gehrig was officially called up to join the Yankees fulltime. For the first few months, Gehrig was a pinch-hitter and back-up position player. Yankee first baseman Wally Pipp had been a staple on the team and had recently come off his best year. When Pipp began suffering from headaches, it afforded manager Miller Huggins the opportunity he had been waiting for. On June 2, 1925, Gehrig was put at first base and would remain there for the next 14 seasons.

He would hit 20 home runs in his limited plate appearances, still good enough for third best behind Bob Meusel (33) and Ruth (25). Two seasons later, Gehrig would officially live up to the “second Babe Ruth” title as the two competed in what would become known as

the Home Run Derby of 1927. Gehrig’s charge to become the season’s home run king pushed Ruth to do something never done before: hit 60 home runs. Gehrig would finish with 47. The Yankees would cap the year by sweeping the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series.

Riding the high of such an immaculate sea son, Ruth and Gehrig set out west to spread the good news of baseball on a barnstorm ing tour. MLB had yet to settle west of the Mississippi, and the two towering giants of the game seemed fantastical. They crushed baseballs, signed autographs, and took photo graphs with fans of all ages. On the stat sheet, Gehrig seemed like a replication of Ruth. Off paper, the two were polar opposites, as if sum moned from different planets. Ruth was built like “toothpicks attached to a piano,” while Gehrig was of “perfect physical condition.” Ruth lived loudly to the point of collapse, while Gehrig lived modestly and avoided the nightlife. Ruth negotiated major contracts, while Gehrig signed whatever the Yankees offered. Ruth was surrounded by women, while Gehrig lived with his parents until he married in 1933. Ruth would restlessly reflect the spendthrift nature of the Roaring ’20s, while Gehrig would exemplify the resolve and frugality of the Depression Era. The Gehrig mythology was hardly of his own creation; but it was created nonetheless.

“Lou Gehrig has accidentally got himself into a class with Babe Ruth and Dempsey and

With his novel ‘The Last of the Mohicans,’ Fenimore Cooper created an archetypal symbol of heroism that has endured in American literature and cinema

WRITTEN BY Andrew Benson Brown

WRITTEN BY Andrew Benson Brown

“

T he Last of the Mohicans” is often dismissed as a boring old novel full of dense descriptions, epito mizing Mark Twain’s definition of a “classic” as “something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.” Twain himself did not think much of its author, James Fenimore Cooper, whose “literary offenses” he lampooned in a famous essay. But Twain’s view is hardly impartial: As a great novelist himself, he needed a literary forebear to overthrow—and what better target than America’s first great novelist? Although it is not taught much in schools these days, “The Last of the Mohicans” is a magnificent adventure story, and its hero, Nathaniel “Natty” Bumppo, is arguably the most influen tial character in all of American literature.

LEFT “The Indian’s Vespers” by Asher Brown Durand, 1847. In this piece, Durand painted references of American landscapes to evoke the ancient roots and yearnings of mankind.

Cooper was born in 1789, growing up in a New York frontier town where he passed his boy hood listening to elderly pioneers tell stories from a bygone era. As a student at Yale, his individualism often brought him into conflict with others. After being expelled for pranks, he retained a lifelong aversion to educated New Englanders. At age 17, he took up sailing, witnessing British oppression firsthand when crew members of the Royal Navy boarded his merchant ship and coerced a fellow sailor into service. After this, he joined the U.S. Navy. Stationed at Lake Ontario, he built ships and explored the wilderness in his spare time. These early experiences taught Cooper to admire the aging settlers he knew as a boy while resenting the civilized people who con tinually pushed back the boundaries of the

ABOVE An illustration by Frank T. Merrill from the 1896 edition of “The Last of the Mohicans” shows Hawkeye, disguised as a bear, attacking Magua in the cave where Alice is held captive.

BELOW “Scene From ‘The Last of the Mohicans,’ Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund” by Thomas Cole, 1827.

unspoiled frontier and made the pioneer’s way of life obsolete. Cooper’s belief that society is a necessary evil bringing law and order, but also greed and cowardice, led him to espouse the morally uplifting benefits of nature. He devel oped this attitude in over 30 novels, in addition to writing plays, short stories, travelogues, and historical works.

He is best known for his series of five nov els known as the “Leatherstocking Tales.” The second of these, “The Last of the Mohicans,” was published in 1826 and is regarded as his masterpiece. Set in 1757, it recounts one of the worst atrocities of the French and Indian War, in which Indian allies of the French massacre a retreating British column following the siege of Fort William Henry. Cooper dramatizes these historical events through the eyes of two fictional daughters of a British colonel and their guides, Mohicans whose tribe is on the brink of extinction (at least in the novel). It is these three protectors—Chingachgook, Uncas, and the adopted frontiersman Natty Bumppo— who represent Cooper’s ideal of virtuous men uncorrupted by urban vices.

The idea of the “noble savage” is an old one going back to the Roman historian Tacitus, who in his book “Germania” idealized the rustic northern tribes at the expense of their Italian conquerors. Later, when America was discovered, many Europeans associated its native inhabitants with a lost golden age where man lived in harmony with nature.

In reality of course, tribal peoples were capable of terrible atrocities and were not particularly noble much of the time. Cooper recognized this. He portrayed frontier life with a brutal realism while capitalizing on the romantic ideal of natural virtue in his heroes. Cooper applied the noble savage ste reotype to Chingachgook and Uncas, but he also updated it to create a character with no prior parallel in fiction. The protagonist of the “Leatherstocking” novels, Natty Bumppo, is always noble but not quite savage—nor quite civilized. A white child educated by Christians but raised by Delaware Indians, his identity is both European and Indian. He embodies the best of both populations with

vvv

Cooper’s belief that society is a necessary evil bringing law and order, but also greed and cowardice, led him to espouse the morally uplifting benefits of nature.

out belonging to either.

In “The Cowboy Hero and Its Audience,” Alf H. Walle describes the way Cooper created “an archetypal symbol of America” by pitting a heroic frontiersman “against an amoral and effete civilized world.” Cooper drew on reallife settlers as models for Bumppo, whose nicknames include Hawkeye, Deerslayer, Leatherstocking, and Long Rifle. While he is skilled in fighting and wilderness survival, what makes him a compelling character is his personal moral code. He distinguishes good from bad by judging people on their own terms rather than according to abstract social norms. He does not coerce others to follow his pri

FIRST

FIRST NAME

NAME

Photo Credits

Photo: Heather Broomhall

Photography for American Essence

Pictured: Super Bowl cham pion Eric Weddle at Iron Mountain Trail, Poway, Calif.

| lightphoto/iStock/Getty Images Plus

6 | Bird of Bliss for American Essence

8 | Courtesy of Englander, Peter Pots Pottery, Afloral, Bedford Collection Mesa Throw, USSheepskin, BridgewaterChocolate

9 | Background: Freepik

Top to bottom: Library of Congress, Rawpixel, bsd stu dio/Shutterstock, Freepik

10–11 | Car illustrations: alfina16 for American Essence

Others: Milos Ruzicka, Mateusz Atroszko, Oldesign, Alitasama, Borphy/Shutterstock

15 | Courtesy of Eric Weddle

| Bird of Bliss for American Essence

| Courtesy of Ethan Bryan

| Mike Hudgens

Photography

| Courtesy of Ethan Bryan

| Background: DistanceO/ Shutterstock

| David Alvarado

| Courtesy of Hayden Flour Mills

| David Alvarado

| Courtesy of Hayden Flour Mills

29–35 | David Alvarado

| Left: Courtesy of Stefan Czarnecki

Right: grafvision/Shutterstock

38–39 | Courtesy of Stefan Czarnecki

40–41 | Courtesy of Andrew Benson Brown

| Yarikart/Shutterstock

44–49 | Courtesy of Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave

| Public domain

| Library of Congress

| FierceAbin/iStock/Getty

Plus

| Trong Nguyen/ Shutterstock

| Public domain

| Left: Library of Congress

Right: National Park Service

| John M. Chase/ Shutterstock

| Public domain

| Top: Public domain

Rawpixel

| Public domain

| Library of Congress

| Public domain

| Library of Congress

| Plane photo: Karol

Ciesluk/Shutterstock

Blue illustrations: Oleksander Logkykh, alya_haciyeva/ Shutterstock Plane illustrations: Amy Han for American Essence

| Public domain

| Courtesy of Montpelier

| Right: Courtesy of Montpelier

Others: Public domain

| Courtesy of Montpelier

| Courtesy of Eileen

| Eddie Bugajewski/ Unsplash

| Public domain

1. False. Though black and white clothing was the fashion of the day in England, this had to do with the expensive nature of black dye. Property inventories made upon the death of Pilgrims prove they wore a variety of colored garments.

2. True. The first gun holster was just a rolled-up leather piece that was stitched together on the ends, typically worn on a belt that didn’t match.

3. False. While early 19th-century urban women had access to factory-made cloth, pioneers did not. Clothing was hand-woven from raw wool, linen, and cotton.

4. True. While Columbus discovered cotton growing in the Bahamas, and there is evidence that it was grown in Mexico, early colonists of Florida and Jamestown imported the first seeds planted there.

5. Tricorne. The hat’s iconic style was fixed during the American Revolution when adjustments were made for military use, such as wearing colored cockades to distinguish rank.

6. Coonskin. Franklin was wildly popular in Paris partly because he pandered to the French view that idealized the uncorrupted frontier lifestyle.

7. Moccasins. The word was generalized by white settlers to refer to all Native American footwear.

8. B. Bloomers. Named for the newspaper editor Amelia Bloomer, who advocated their use. Women often suffered injuries while cycling due to their skirts getting caught in the spokes.

9. C. Hairstyles were short. Hemlines usually ended mid-calf. Heels were low and chunky. Eyebrows were plucked and penciled. Lipstick was dark red. Nonprecious costume jewelry became popular with the development of plastics.

10. A. Trousers were held up by suspenders, as pioneers did not use belts. Neither did they have zippers or wear silk. Shirts had long sleeves and long tails.

LEFT “Story of Golden Locks” by Seymour Joseph Guy, circa 1870. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

AMERICAN PAINTER Seymour Joseph Guy (1824–1910) made a name for himself painting childhood genre scenes. He depicted three of his nine children in the charming painting “Story of Golden Locks.” In the picture, Guy’s daughter animates the fairy tale so well that her younger brother holds his sister close to comfort her, as they both wait with bated breath to hear if Goldilocks will escape the

three bears. Their older sister holds the book open so we can see Goldilocks jump from the window to safety. Born in England, Guy copied old master art works at the British Museum and studied in the studio of painter Ambrosini Jerôme. Guy and his wife immigrated to America in 1854, and he had a studio among the artists of Brooklyn and then Manhattan. •

This book expounds upon the profound principles of Truthfulness, Compassion, and Tolerance. It focuses on a long-forgotten term called “cultivation,” and the importance of moral character on one’s path to spiritual perfection. The book explains the role of karma as the root cause of illness and tribulations, along with many other mysteries of life and the universe.

Zhuan Falun, the main text of the spiritual practice Falun Dafa, was a national bestseller in China in the 1990s, and has since been translated into over 40 languages. Find out why it has captured the hearts and minds of tens of millions of people in over 100 countries worldwide!

FaYuanBooks.com

Scan the QR code with your phone camera to open our website, or visit:

“Falun Gong is, in my judgement, the single greatest spiritual movement in Asia today. There’s nothing that begins to compare with it in courage and importance.”

“What made Falun Gong stand out from other qigong exercises and meditation practices was a moral system compassion, truthfulness, and forbearance unmistakably Buddhist in origin.”

Mark Palmer FORMER U.S. AMBASSADOR

Arthur Waldron LAUDER PROFESSOR, UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA