BRIMO DE LAROUSSILHE PARIS

BRIMO DE LAROUSSILHE

Exhibition from September 15th to October 14th 2023

7, quai Voltaire - 75007 Paris

T +33 1 42 60 74 76

www.brimodelaroussilhe.com

e-mail: galerie@brimodl.com

MEDIEVAL ENAMELS

MARIE-AMÉLIE CARLIER

Translated from the French by FRANK DABELL

Enamel work is not a Medieval innovation, but the development of enamelling, especially on copper, from the Romanesque period on, is one of the most remarkable and perhaps most seductive phenomena in the history of precious works of art in the Medieval period.

While enamels in the region of the Meuse can be counted among the most beautiful works of the period, the evolution of the art of enamelling in Northern Europe was relatively brief. In France, on the other hand, the flowering of Limoges Work endured for nearly two centuries, from roughly the middle of the twelfth century to the beginning of the fourteenth century. Limousin enamel owes its success especially to the combination of colour, with the predominant presence of lapis blue, and sculpture, crafted on copper sheets. The aesthetic qualities of these works, their powerful visual impact, the readability of their decorative content, the solidity of the pieces, and their cost, quite reasonable with respect to works in gold or silver enhanced with hardstones and precious stones, also account for the extraordinary spread of Limoges enamels throughout Europe.

The decline in of champlevé enamels of Limoges at the beginning of the 1300s corresponds in part to the increased popularity of translucent enamels in gold or silver basse-taille. This technique, invented in Siena at the end of the thirteenth century, gradually emerged in France, particularly at the beginning of the fourteenth century, and lasted until the end of the Medieval period around 1500, as seen in the three pages in gold and translucent enamel from an enamelled gold book made for Anne of France (cat. 36).

Brimo de Laroussilhe holds a special place in the history of the reception of Medieval enamel work. Founded in 1908 by Nicolas Brimo, with the association of his brother-in-law Lucien Lascombe de Laroussilhe, the gallery very soon began to specialize in precious works of art from the Middle Ages. Photographs of the gallery’s early twentieth-century display cases show a profusion of enamelled pieces, principally consisting of Limoges Work.

Some of the most important pieces of Medieval enamel work now housed in great museums were handled by Brimo de Laroussilhe. Among these is the so-called Armilla of Frederick Barbarossa (fig. 5) from the Cathedral in Vladimir, purchased by the gallery during the sales made by Soviet Russia in 1933 and sold to the Musée du Louvre in 1934.

Since the 1990s, with the decision to focus exclusively on Medieval and Renaissance art, the gallery’s interest in enamel works never flagged, and we have had the good fortune of seeing many major works pass through our hands.

Among these we can make mention of the phylactery from the Abbey of Lobbes (fig. 1), now in the Wyvern Collection in London; the three medallions crafted in Silos or Limoges (fig. 6), formerly in the Stoclet collection and now housed in the Louvre; the Christ in Majesty from the altar frontal of Ourense Cathedral (fig. 7), now in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles; the beautiful chasse of the Three Kings in the Musée de Cluny, Paris (fig. 2); and the small translucent enamel diptych leaf dating from between 1320 and 1330, also in the Musée de Cluny (fig. 3).

These works, like those presented in this catalogue, bear witness to the startling richness and variety of Medieval enamel work, which continue to fascinate us to this day.

Fig. 7 Christ in Majesty from the altar frontal of Ourense Cathedral, Limoges, circa 1188. Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Fig. 7 Christ in Majesty from the altar frontal of Ourense Cathedral, Limoges, circa 1188. Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum.

CATALOGUE

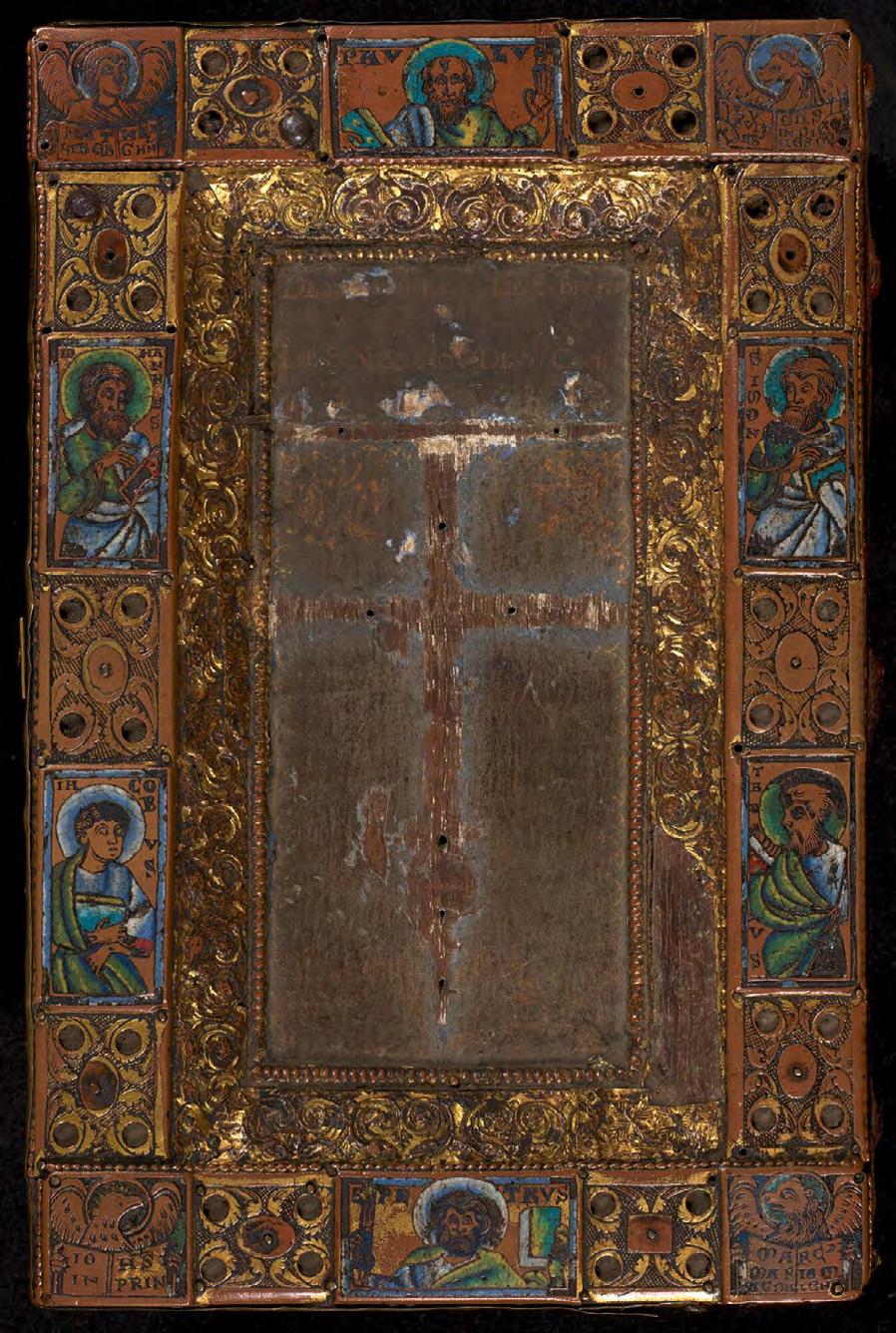

FOUR PLAQUES WITH SYMBOLS OF THE EVANGELISTS

Meuse Valley, circa 1160

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel

Each plaque: height 1½ in. (3.8 cm), width 1½ in. (3.8 cm)

PROVENANCE

William Gott collection (Leeds), during the 19 th century; John Gott [1830-1906]; with Sotheran, London1; C. W. Dyson Perrins [1864-195]; Major J. R. Abbey [1894-1969]; Brimo de Laroussilhe; E. and M. Kofler-Truniger collection (Lucerne); Ronald Lauder collection (New York).

LITERATURE

Warner, G., Descriptive Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts in the Library of C. W. Dyson Perrins Oxford University Press, 1920, pp. 76-77, no. 25.

The four symbols of the Evangelists are represented bust-length, each holding a small panel bearing his name, enamelled in blue on the reserved metal. Each figure appears within a thin blue enamel frame surrounded by a thin white border. The four plaques were designed to be attached to a wooden support, as shown by the holes in each of the four corners. The outer edges are beaded.

The square shape of these four plaques and their dimensions and iconography might prompt us to believe that they could have formed part of a staurotheke (reliquary of the True Cross) like the one housed in the Musée Dobrée, Nantes, which bears identically arranged symbols of the Evangelists in each corner. 2 This type of representation is also incorporated in other bindings such as those of the Dinant Gospels in Manchester, 3 the Saint Trond Lectionary in Düsseldorf, 4 and a Gospel book in Brussels. 5

The provenance of this tetramorph – which until the 1960s still formed part of the binding of a copy of the Commentaires des Psaumes of Petrus Lombardus, a Northern French manuscript of about 1200 6 – leads us more plausibly to the second hypothesis. An inscription on the first folio of this manuscript tells us that the binding was reworked in 1721 when it was still housed in a monastery in northern France.7 As has been pointed out by G. Warner, 8 it is likely that the eighteenth-century renovation retained parts of the ancient binding, and one can thus imagine that the four plaques with Evangelical symbols formed part of the binding of the manuscript before that date.

The palette of the enamelling shows a range of cool colours, with a harmonious combination of yellow-fringed green and blue, becoming bolder with deeper blue or fading to white. The haloes of Matthew, Luke and Mark are blue with a white border, while that of John’s eagle is surrounded by a yellow border. This variant reflects a desire to diversify the palette of this plaque, which except for the red-tipped ends of the wings, consists solely of a rich range of blues.

In general, these four plaques reflect a very high quality of execution, as shown by the confident engraving around the reserved spaces of gilded copper. The supple, fine spared lines that define the contours and principal forms of the bodies are particularly evident in the figure of the eagle. Moreover, the elevated quality of handling is fully perceptible because of the very good condition of the gilding, which reveals both the qualities of the design and the tonal richness of the enamel.

In many respects, this tetramorph appears to derive directly from the great Mosan creations of the 1160s. The classicism of the beautiful oval face of Saint Matthew’s angel, the treatment of his hair and the palette of the enamelling enable us to associate the style with that of the Stavelot Triptych in the Morgan Library,9 which can be dated to about 1156-1158.

The style is also close to that of the pendant in the Cleveland Museum of Art, datable to about 1160.10

These various parallels, the stylistic features of the four plaques and their high quality of execution allow us to propose that they were crafted immediately after the last-mentioned works, probably around 1160.

1. Bibliotheca Pretiosa, sale catalogue, London, Sotheran, 1907, no. 301.

2. C osta , 1961, p. 100, no. 20; G eorG e, 2014, pp. 73-78.

3. John Rylands Library, Ms. Lat. 11.

4. Düsseldorf, Hauptstaatsarchiv, Hs. G XI, I; see Cologne - Brussels, 1972, p. 256, G. 18.

5.Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, Ms 14 970.

6. See The Dyson Perrins collection. Part III, Fifty-nine Illuminated Manuscripts the Property of the Late C. W. Dyson Perrins, Sotheby & Co., London, 29 November 1960, pp. 22-23, lot 102.

7. At the foot of the recto of the first folio: “Hunc librum religavit D. Philippus Fisen hujus monasterii religiosus et Cantor, 1721”. See Warner, 1920, pp. 76-77.

8. Ibidem

9. Voelkle, 1980.

10. k lein , FlieG el and B rilliant, 2007, pp. 136-137, no. 45; G eorG e, 2014, pp. 114-118.

PLAQUE FROM A CROSS: THE SACRIFICE OF THE LAMB AND THE SIGN OF THE TAU

Meuse Valley, circa 1160-1170

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel

Height 3 in. (7.7 cm), width 2½ in. (6.3 cm)

PROVENANCE

E. Guilhou collection (Paris); Seligmann collection (Paris); Georges E. Seligmann (New York).

EXHIBITED

New York, Medieval Art from Private Collections, The Cloisters, October 30 th 1968 - March 30 th 1969, no. 148.

LITERATURE

Verdier, Ph., “A Mosan Plaque with Ezechiel’s Vision of the Sign Thau (Tau) – Addendum”, Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, XXIX-XXX (1966-1967), p. 67.

Gomez-Moreno, C., Medieval Art from Private Collections. A Special Exhibition at The Cloisters, exh. cat. (New York, The Cloisters, October 30 th 1968 - March 30 th 1969), New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1968, no. 148.

MorGan, N., “The iconography of twelfth century Mosan enamels”, in Rhein und Maas, Kunst und Kultur 800-1400, II, Cologne, 1973, p. 265.

Pressouyre, L., “La ‘Mactatio Agni’ du portail des cathédrales gothiques et l’exégèse contemporaine”, Bulletin Monumental, vol. 132, 1974, pp. 58-59.

Verdier, Ph., “Émaux mosans et rhéno-mosans dans les collections des États-Unis”, Revue Belge d’Archéologie et d’Histoire de l’art, XLIV, 1975, pp. 34-35.

Brodsky, J. “Le groupe du triptyque de Stavelot: notes sur un atelier mosan et sur les rapports avec Saint-Denis”, Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale, XXI, 1978, p. 108, note 24, pl. V, fig. 12.

Carlier, M.-A. “Plaque de croix typologique: Le sacrifice de l’Agneau et le Signe du Tau”, in GeorGe, Ph. (ed.), L’œuvre de la Meuse, Feuillets de la cathédrale de Liège, 2014, pp. 95-97.

The dimensions and iconography of this plaque suggest that it may originally have formed part of a large typological cross. Frequently found in the region of the Meuse, such crosses expressed parallels between the Crucifixion, or Christ in Majesty, and various Old Testament episodes prefiguring either Christ’s sacrifice or the shape of the Cross, such as Abraham and Isaac, the Offerings of Cain and Abel, the Widow of Sarepta, or — evidently — the Sign of the Tau.

This learned taste for correspondences between Old and New Testaments, which spread through the Mosan region in an unprecedented way, is directly tied to the theories espoused by the theologians of the time. Among those in the forefront of the discussion was Rupert, a monk from Liège who became Abbot of Deutz in 1120. In his writings, Rupert of Deutz gives a wide-ranging treatment of the Gospel story, reading it in symmetry with Old Testament narratives. These theological considerations profoundly marked the work of Mosan enamel artists, as one can see on numerous crosses or individual plaques from dismembered crosses.

The scene of Paschal immolation, in which the letter tau (T) is inscribed in lamb’s blood on the lintel of the doors of the Israelites as a sign of Salvation before the tenth plague of Egypt (Exodus 12: 21-22), is among the typological parallels frequently adopted in Mosan enamels. The subject appears in various examples, including the foot of the Cross of Saint Omer,1 and on the crosses in the Royal Museum in Brussels, 2 the British Museum, 3 Vienna, 4 as well as on the reliquary cross in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 5 two related plaques in the Musée du Louvre, 6 and another plaque in the British Museum.7

Sometimes, as in the two related plaques in the Louvre, the scene of the anointing of doors with the blood of a lamb is presented as a pendant to that of the “man clothed in linen” who marks the Tau on the forehead of the righteous, according to the vision of the Prophet Ezekiel (9: 3-4). The two iconographical subjects are very often associated, and generally present a conjunction of elements even when they are treated independently. As Philippe Verdier and Léon Pressouyre have underlined, the man inscribing the Tau on the front of a house — illustrating the passage from Exodus — does not use a sprig of hyssop dipped in lamb’s blood, as in the scriptural text, but a goose quill, as referred to in Ezekiel’s vision, and as seen here.

On the present plaque formerly in the Seligmann collection, the sacrifice of the lamb is specified by the inscription “MACTATIO AGNI”, as on the Saint Omer crossfoot or the typological cross in Brussels. However, the slaughtering of the lamb is very often relatively inconspicuous, with the animal shown with its throat slit in the doorway of the house, its blood collected in a cup. Emphasis is given to the related image of anointing the doors with the blood of the lamb, indicated by the words “SIGNUM TAU” (once again drawn from Ezekiel), as in most of the other known instances. The subject is known in a number of variants in Mosan enamel art. The composition of the Seligmann plaque limits itself to the three essential elements of the story: the slaughtered lamb, the figure inscribing the sign of the Tau, and the house, which approximates the form of a church, with a gabled façade seemingly flanked by a pair of towers.

The economy of means used in this image, and the choice of a beardless and simply clothed youth for the figure inscribing the Tau, invite direct comparison with the plaque on the right terminal of the typological cross in the British Museum, which can also be dated to the years between 1160 and 1170. 8

1. See C olo G ne-B russels , 1972, pp. 254-255, no. G17.

2. Ibidem, p. 258, no. G21.

3. s tratFord, 1993, cat. 4, pl. IX.

4. m orG an , 1973, p. 264, fig.1.

5. Pressouyre, 1974, p. 58, fig. 6.

6. G aBorit, 2005 p. 173, figs. 184-185.

7. s tratFord, 1993, cat. 13, pl. XIX.

8. Ibidem, cat. 4, pl. IX.

PLAQUE WITH A FIGURE OF HUMILITAS (HUMILITY)

Meuse Valley, circa 1170

Copper, chased and gilt; champlevé enamel Height 2 3/8 in. (6.1 cm), width 3 1/8 in. (7.9 cm)

PROVENANCE

Adolphe Stoclet collection (Brussels); Philippe Stoclet collection; Keir collection.

EXHIBITION

Masterpieces from the Keir Collection, British Museum, London, 1981.

The Keir Collection, Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1983.

LITERATURE

BorChGraVe d’Altena , J. de, « Des figures de vertus dans l’art mosan au XIIe siècle », in Bulletin des musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, I, 1933 ; p.17, fig. 16.

KatzenellenBoGen, A., Allegories of the Virtues and Vices in Medieval Art, London, 1939, pp. 48-49 (note 2).

Verdier, Ph., « Un monument inédit de l’art mosan du XIIe siècle. La crucifixion symbolique de la Walters Art Gallery », Revue belge d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art, XXX, 1961, p. 154, fig. 25.

MorGan, N.« The iconography of twelfth-century Mosan Enamels », in Rhein und Maas, Kunst und Kultur 800-1400, II, Cologne, 1973, pp. 263-278, p. 273 (note 66).

StratFord, N., « Plaque: Humilitas », in Gauthier, m.-m and François, G., Medieval Enamels, Masterpieces from the Keir Collection, London, 1981, pp. 32-33, no. 47.

This rectangular plaque is surrounded on all sides by beading. Attachment holes are visible in each corner. A half-length figure of a female Virtue, winged and haloed, appears in the middle of the plaque, placed within a blue and white enamelled frame. She holds a crown in her right hand, and in her left, similarly covered by a fold of her mantle, she holds an enamelled red cross, its top extending over the enamel framing border. She wears a green tunic with yellow highlights and her mantle combines turquoise, blue and white tones. Her wings, dominated by green and blue, are simply designed and topped by a roll of deep red lined with white. Facial features, as well as hair, Adam’s apple and part of the left hand, set against the gilded background of the plaque, are defined by blue enamel. The face of this Virtue is typical of Mosan enamel work of the last third of the twelfth century: it is oval in form and has a fairly strong nose, and the round eyes, slightly close to one another, are placed under assertive eyebrows, one of them extended by a single line of the tool into the bridge of the nose.

The upper part of the plaque bears the name of the Virtue in blue: “HUMILITAS” (Humility). The manner of writing and the arrangement of the letters on both sides of the figure are also characteristic of Mosan workshop practice in the last third of the twelfth century.

The representation of a winged Virtue, shown frontally, can be found in a number of Mosan works of the last third of the twelfth century,1 such as the Reliquary Cross in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, the gable of the reliquary casket of Saint Gondulphe in Brussels, the phylactery from Waulsort in the Museum in Namur, or the two plaques which combine the representation of Virtues with an embodiment of the first and fourth images of FIDES and RELIGIO (Faith and Religion) in the British Museum. 2

The latter images combine the representation of Virtues with an embodiment of the first and fourth Commandments. The iconography of the Ten Commandments, which scarcely appears outside Mosan art of the twelfth century, is frequently associated with figures of Virtues, most often resembling the one discussed here, that of a half-length Angel with wings spread. We may also underline that the plaque with Humilitas is very close in spirit to the beautiful appliqué gilt bronze figure, once also in the Stoclet collection, of an Angel holding the text of the sixth commandment, “NON OCCIDES” (“Thou shalt not kill”). 3 The classicism of the oval face, the centrally-parted hair, rolled around the temples, and above all the spirituality exuded by this figure are all elements shared by these two works, once in the same collection.

Among the representations of Virtues in Mosan art that have come down to us, no other unites the two attributes held here by Humilitas: the cross and the crown. In the Waulsort phylactery, Humilitas holds the cross, but her other hand holds a disc bearing the inscription “EXALTIO”.

A plaque with iconography very close to the one in the Stoclet collection was once housed in the collection of Dr. Leopold Seligmann. 4 The centre of this rectangular plaque has a haloed and winged figure wearing

a crown, with the enamelled inscription “CARITAS” running vertically to its left. The quality of the photograph published in the catalogue of the Seligmann collection does not really allow one to establish possible similarities of style between the two plaques, but whatever these may be, their difference in size suggests that they did not come from the same object. 5 It is in any case relatively difficult to be certain about the type of work to which the Stoclet plaque could have belonged. It is not impossible, given its form and dimensions, that this plaque may have been placed at the base of a cross. This is all the more likely if one considers that Humility is at the root of all the Virtues, and that the attributes carried by Humilitas refer directly to the Passion of Christ. 6

1. See Verdier, 1961, pp.115-175.

2. StratFord, 1993, nos. 11-12, pp. 83-85.

3. See D urand, 2003, no. 6, pp. 24-25.

4. Die Sammlung Dr Leopold Seligmann, Köln, Ball & Graupe, Berlin, April 29 th, 1930, lot 125d, pl. XXXV.

5. The dimensions of the plaque in the Seligmann collection are given in the sale catalogue as 5.7 x 6.6 cm; those of the plaque in the Stoclet collection measure 6.1 x 7.9 cm.

6. StratFord, 1981, p. 33. At the same time, as Neil Stratford has underlined, this plaque could equally have functioned on a reliquary or on a binding.

PLAQUE: SAINT NICHOLAS

Rhenish-Mosan, circa 1180

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel

Height 4 in. (10 cm), width 2¾ in. (7 cm)

PROVENANCE

H. Baumel collection (Paris); Simon Seligmann collection (Paris); Georges

E. Seligmann (New York).

LITERATURE

HoFFmann, K., The Year 1200, exh. cat., (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 12 th - May 10 th 1970), New York, 1970, p. 182, no. 188.

MorGan, N., “The iconography of twelfth-century Mosan enamels”, in Rhein und Maas, Kunst und Kultur 800-1400, II, Cologne, 1973, p. 275, note 173.

Verdier Ph., “Émaux mosans et rhéno-mosans dans les collections des États-Unis”, Revue belge d’Archéologie et d’histoire de l’art, XLIV, 1975, pp. 64-65.

EXHIBITED

New York, The Year 1200, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970.

The plaque is shaped like a mandorla, defined by fine lines of blue and white enamel and set within a border of dense beading. The image is surrounded by an inscription that identifies the holy archbishop: “ARCHIEPISCOPVS SCS NICHOLAVS”. The figure is haloed, standing and dressed in a dalmatic and chasuble of the Roman tradition. Saint Nicholas also wears a pallium bearing enamelled crosses; he holds the crozier in his right hand and proffers an open book with his left, with the inscription “PAX VOBIS” (Peace be with you). Here, the mandorla and inscribed declaration, recalling Christ’s words to his Apostles after the Resurrection, aim to establish a parallel between the Holy man and the Redeemer. It should be pointed out that the representation of a Saint within a mandorla is relatively uncommon, the format being traditionally reserved for figures of Christ or the Virgin Mary in Majesty.1 The shape of the plaque does not make it possible to precisely identify the object of which it originally formed part, but this was probably a small altar or reliquary. On the other hand, the iconography appears to be sufficiently specific to enable us (following Nigel Morgan) to propose that the object was dedicated to Saint Nicholas. 2

In many respects, the style of the plaque relates to Mosan works circa 1160-1170: the palette of the enamels, the coloured modelling of drapery, the thin blue and white enamelled border, and the formal, hieratic attitude of the figure. However, the summary treatment of hands, the somewhat reduced proportions of the head and above all, the slightly flattened style of the face seem to stand out from the Classicism that generally predominates in purely Mosan enamels. These elements explain why the plaque

was attributed by Konrad Hoffmann to a Cologne workshop in the decade 1180-1190; 3 he suggested comparing the angular style of the drapery in the Saint Nicholas plaque with that of the figures of bishops in the medallions of the roof of the reliquary shrine of Saint Heribert, executed in Cologne between 1160 and 1170. 4 While a dating around 1180 seems entirely justified on grounds of style, the attribution to the Cologne school seems less clear, and precise historical placement is hindered by the absence of a secure comparison. According to Philippe Verdier, the Seligmann plaque, which he compares in this respect with the one in the Hesse Museum in Darmstadt,5 can more plausibly be classified among the enamels linking the Meuse and Rhine workshops in the period around 1180. 6

1. See for example the plaque with Christ in Majesty on the cover of the Saint Trond Lectionary (C olo G ne – B russels , 1972, I, G. 18, p. 256) and the plaque with the Virgin in Majesty on the phylactery pendant in the Cleveland Museum of Art (K lein , FlieG el and B rillianT, 2007, pp. 136-137, no. 45).

2. M orG an , 1973, p. 275, note 173.

3. H o FFmann , 1970, p. 182, no. 188.

4. S Chnitzler, 1959, pls. 91-92.

5. KötzsChe,1973, pp. 151-170, p. 154, fig.5.

6. Verdier, 1975, pp. 64-65.

HALO AND DECORATIVE PLAQUE

Rhenish-Mosan, circa 1180-1200

Halo: height 13/16 in. (2 cm), width 2 5/8 in. (6.6 cm)

Plaque: height 1 3/16 in. (3 cm), width 2 ½ in. (6.3 cm)

Halo:

PROVENANCE

Dr. Leopold Seligmann collection, Cologne (sale, Berlin, 28-29 April 1930, lot 125e, pl. XXXV); E. and M. Kofler-Truniger collection, Lucerne, before 1964; Keir collection.

LITERATURE

SChnitzler, H., BloCh, P. and Ratton, C., Email, Goldschmiedeund Metallarbeiten, Europäisches Mittelalter, Sammlung E. und M. Kofler-Truniger, Luzern, vol. II, Lucerne and Stuttgart, 1965, no. E 35, p. 19, pl. 36.

EXHIBITED

Zurich, Sammlung E. und M. KoflerTruniger, Luzern, Kunsthaus, 1964.

Kansas City, The Keir Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1983.

The halo, cut into a crescent shape and decorated with the upper part of a foliate motif, reserved and gilded against a blue enamelled ground, bears the inscription “SANCTA SENC(IA)”.

The lettering refers to Saint Sencia, one of the companions of Saint Ursula, and thus one of the legendary eleven thousand virgins massacred at Cologne, together with Ursula, upon their return from a pilgrimage to Rome.

The female saint’s identity and the presence of the halo in the collection of Leopold Seligmann in Cologne in the early twentieth century have led to the proposal that the piece formed part of the great chasse of Saint Ursula housed in Cologne Cathedral.1 This reliquary chasse was heavily restored in the nineteenth century, and it cannot be ruled out that this halo was substituted during that period.

Likewise, the small rectangular decorative plaque is probably a fragment of a large Rhenish reliquary chasse from the end of the twelfth century. It is embellished with a row of circles between two rows of semi-circles, all set on a blue enamelled background. The centre of each circle and semi-circle bears a quatrefoil rosette motif on an enamelled turquoise ground, and each row is separated by two other rows of small white enamelled discs. The whole group is framed by a fused band of turquoise and white enamel. The sides of the plaque are formed of the traditional beading found in Rhenish-Mosan enamel work.

Many plaquettes of this type have come down to us, either decorating various reliquary chasses2 or as isolated pieces, 3 bearing witness to the richness and refinement of the ornamental vocabulary used by Rhenish enamel artists at the end of the twelfth century.

6 SAINT JOHN THE EVANGELIST

Germany (Saxony?), mid-twelfth century

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel

Height 5 3/8 in. (13.6 cm), width 2 11/16 in. (6.8 cm)

The plaque has an arched top and a blue enameled border. The figure is that of an Apostle, standing and with the Book of Scriptures in his right hand. The inscription next to him, “S / IHS” abbreviates his name in Latin, Sanctus Iohannes , that is, Saint John the Evangelist.

This plaque belongs to a series of eight others, similar in form, proportion and style, each with an Apostle: Saint Bartholomew, Saint Thomas , Saint Simon and Saint Jude in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,1 Saint Peter in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 2 Saint James in the Art Institute, Chicago3 , Saint Philip in the Museum August Kestner, Hanover, 4 and Saint Matthew in a private collection.5

We may note certain differences between these plaques, especially the framing border, which consists of blue enamel in some cases, and a simple guilloché motif in others. In addition, the Apostles are represented either standing or seated on an enamelled bench; and their haloes are sometimes entirely enamelled, while in others, the halo is formed only of a ring of enamelling. However, these differences in no way rule out the possibility that all nine plaques originally formed part of a single work, 6 perhaps an altar frontal or a large reliquary chasse.

This group of Apostles has also been associated with three rectangular plaques with historiated scenes:7 the Nativity in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Adoration of the Magi in the Saint Louis Art Museum 8 and the Massacre of the Innocents in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.9

These three plaques present similar style and dimensions. Nonetheless, there too, the borders differ from one piece to another. They are traditionally believed to come from a single object, as confirmed by their iconography. The hypothesis that they belong to the same ensemble as the Apostle plaques seems entirely appropriate, but in any case, it is certain that they all came from the same workshop, even if they did not belong to the same work.

Yet their attribution poses some problems: the style and palette of the enamels, and certain details, such as the foot of the Saint John , which encroaches on the enamel border, reveal the clear influence of works from the Rhine-Meuse area. However, the very individual drawing style of some of the faces, with their particularly large brows, emphatic features and rounded eyes, or the exaggerated, dramatic quality of the Massacre of the Innocents, make locating the workshop more challenging. In 1929, Borenius has suggested that the plaques in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the one now in Saint Louis were Mosan,10 but since then all of them have more rightly been given to a German workshop, possibly located in Saxony.11

1. The plaques with Saint Bartholomew (13 x 7.1 cm) and Saint Thomas (12.9 x 7.3 cm), inv. nos. 17.190.442 and 17.190.443, were both in the collection of Georges Hoentschel before passing to that of J. Pierpont Morgan. The plaques with Saint Jude (13.4 x 6.4 cm) and Saint Simon (13.4 x 6.5 cm), inv. nos. 41.100.141 and 41.100.142, were in the Stroganoff collection in Rome and then in that of George Blumenthal.

2. 13.3 x 7 cm. Acquired from Henri Daguerre in 1928 (Inv. 44.0101).

3. 13.2 x 6.5 cm. Formerly in the collection of Kate S. Buckingham (Inv. 1943.67).

4. Inv. no. 3575.

5. On loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York between 1979 and 2010 (L. 1979.37); Sotheby’s sale, New York, January 27th 2011, lot 389.

6. Some of these differences are visible, for instance, in the plaques with Saint Bartholomew and Saint Thomas now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These two pieces have different birders and haloes, but their close resemblance and shared provenance from the Georges Hoentschel collection attest to their common origin. See Pératé, 1911, nos. 18-19, pl. VIII.

7. See Ostoia , 1969, no. 44, pp. 98-99, p. 255.

8. For the plaque in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the one now in the Saint Louis Art Museum, formerly in the Hohenzollern collection, see B orenius , 1929, pp. 93-94.

9. Inv. 17.190.444.

10. See B orenius , 1929.

11. Vera K. Ostoia had suggested that there were certain similarities with works from Hildesheim or Northern Germany (Ostoia , 1969, p. 99); currently the plaques in the Metropolitan Museum of Art are presented as German, possibly Saxon, and dated to about 1150.

PLAQUE: THE CRUCIFIXION

Lower Saxony (Hildesheim?), circa 1170-1180

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel

Height 2 in. (5.3 cm), width 2 5/8 in. (6.8 cm)

PROVENANCE

Adolphe Stoclet Collection (Brussels).

LITERATURE

GoidsenhoVen, J.P. van (ed.), Collection Adolphe Stoclet (première partie) Choix d’œuvres appartenant à Madame Féron-Stoclet, Brussels, 1956, p. 174.

KemPer, D. Die Hildesheimer Emailarbeiten des 12. und 13. Jahrhunderts, Regensburg, 2020, pp. 496-497.

This rectangular plaque is surrounded by a reserved smooth gilt border. Four holes would have allowed its attachment to a wood core, thus securing it to the object which it originally adorned. Its size and shape indicate that it could have formed part of a portable altar1 or an element of a binding board.

The composition reduces the representation of the Crucifixion to its essential elements: Christ on the cross is flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist who both adopt the same gesture of affliction, their heads slightly inclined towards the body of Christ. In typically Romanesque manner, the size of the figures here is adapted to their importance.

The supple design of the reserved and gilded figures, as well as the palette of the enamelling, make it possible to attribute this plaque to workshops active in Lower Saxony, in particular Hildesheim and Brunswick, during the third quarter of the twelfth century. In the years 1170-1180, Lower Saxon workshops produced champlevé enamels with composition that were always extremely clear, in which the characters, entirely reserved and gilded, stand out against an enamel ground with a palette restricted to just a few pure colours: deep lapis blue, bright green and white. The Reliquary of Saint Henry 2 and the portable altar with Christ nailed to the Cross , 3 both housed in the Musée du Louvre, provide good examples of the work carried out in these workshops. One could also compare the plaque attached to the binding board of the Saint Godard Gospels, 4 housed in Trêves, attributed to a Hildesheim workshop of about 1170-1180, which features not only the elements mentioned above, but the gently dotted turquoise blue enamel, here visible on the Cross.

1. For example of the type made by Eilbertus of Cologne (Berlin, Kunstgewerbemuseum): see KötzsChe, 1973, p. 215, figs. 35-36, pl 9.

2. See G aBorit, 2005, pp. 178-179, 182; B aG noli, K lein , Mann and Ro Binson , 2010, p. 83, no. 39.

3. See G aBorit, 2005, pp. 180-182.

4. See Lu Ckhardt and Nieho FF, 1995, I, g. 32, p. 512-516, fig. p. 515; Kem Per, 2020, Tri2, pp. 515-522.

8 TWO PLAQUES: BUSTS OF SAINTS

Grandmont workshop, Limoges, circa 1185-1195

Copper: engraved, stippled and gilt; champlevé enamel Width 3 ¾ in. (9.6 cm) and 3 7/8 in. (9.9 cm)

PROVENANCE

Treasury of Rocamadour (Lot), before 1890; Victor Martin Le Roy collection, before 1900; J.-J. Marquet de Vasselot collection.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Petit Palais, Exposition universelle de 1900, Exposition rétrospective de l’art français des origines à 1800, Paris, 1900, no. 2429, p. 292.

LITERATURE

RuPin E., L’Œuvre de Limoges, Paris, 1890, pp. 334-335, fig. 401.

RuPin E., Rocamadour. Étude historique et archéologique, Paris, 1904, pp. 303304.

Marquet de Vasselot, J.-J., Catalogue raisonné de la collection Martin Le Roy, I, Orfèvrerie et émaillerie, Paris, 1906, nos. 19-20, pp. 31-32, pl. XIV.

SouChal, G., « Autour des plaques de Grandmont : une famille d’émaux limousins champlevés de la fin du xiie siècle », Bulletin monumental, CXXV, 1967, pp. 54-55.

Gauthier, M.-M. and François, G., Émaux méridionaux Catalogue international de l’Œuvre de Limoges, I, L’Époque romane, Paris, 1987, nos. 275276, p. 220, pl. CCXXXII, fig. 766-767.

These two mandorla-shaped plaques each have a gilt medallion in the middle, outlined in turquoise enamel and set against a lapis lazuli blue ground. Flanking each medallion is a floral motif with two long enamelled petals spreading from the lateral holes used for attaching the plaques.

At the centre of each medallion, reserved and gilded, is the figure of a saint, probably an apostle, shown emerging from wavy clouds; one of the latter has curved extensions ending in palmettes. Both figures wear ample dark blue cloaks over a light blue robe, with a broad ornamental band across the collar enamelled in red and embellished with a dot motif or a grid motif using the gilding left in reserve.

The flesh of the face and neck on both figures is described in white enamel with a very slight pink hue. Hair and eyes are in red enamel, and eyebrows are accentuated by a very fine line of blue enamel. Meticulous stippling defines all the reserved parts of the faces, clothing and ornamental areas. The style of the figures is uniform, yet one can appreciate individual features, one more stocky, with a relatively broad face and more rounded cheeks, the other more slender and finer.

At the end of the nineteenth century, these two plaques were remounted on a composite chasse in the treasury at Rocamadour, 1 with other elements datable to the thirteenth century, to judge by the engraving published by Ernest Rupin in 1890.

Although their Medieval provenance remains unknown, the style, tonalities of the enamel and the technique of these two plaques can be associated with a small group of works created specifically for the Abbey of Grandmont and its subordinate structures at the end of the twelfth century, roughly between 1185 and 1195.

Geneviève Souchal was the first to identify this group, principally composed of elements from large-scale crosses, showing the same techniques and style as the two large plaques from the high altar of Grandmont, which were executed between 1189 and 1190 and are now housed in the Musée de Cluny in Paris. 2

The main characteristics of this very distinct workshop are the enamelling of the flesh parts, the presence of red enamel incrustations setting off hair, beard and eyes, and facial types marked by eyebrows extending into the bridge of the nose, as well as mouths and chins expressed by small curved lines. Likewise, the palette of the enamels, with an emphatic use of marbled pink or white, highly contrasting colours, and above all delicate stippling which enlivens every line in the reserved areas, are all entirely typical of the Grandmont group.

The works in this little group, also distinguished by their balanced compositions and a true sense of monumentality in the design of the figures, represent a rare stylistic trend in the art of Limoges. This is very different from pieces with a vermiculated ground, even if those were created in the same period. At the same time, as Geneviève Souchal has pointed out, the two plaques formerly in the Martin Le Roy Collection show a certain coexistence of gilt and enamelled grounds. Indeed, here the gilded circles containing the champlevé bust figures are set against a deep blue enamel ground decorated with polychrome palmettes, as in the first examples of pieces entirely set against an enamel ground. 3

It is hard to establish with certainty the sort of object to which these plaques could have belonged, since such mandorlas appear on very disparate Limousin artefacts. Nonetheless, the size of the two ovals suggests that they may have adorned a large reliquary chasse. 4

1. This chasse was sold by the church at the end of the nineteenth century; it originally contained relics of Saint Blaise (see Ru Pin , 1890, pp. 334-335 and Ru Pin , 1904, pp. 303-304). The two plaques were already independent items when they appeared in the 1900 Paris Exposition.

2. S ou Chal, 1967, pp. 21-71. For the two plaques from the high altar of Grandmont, now in the Musée de Cluny, see S ou Chal, 1962, pp. 339-357; and TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm , 1996, no. 57, pp. 215-217.

3. S ou Chal, 1967, p. 54.

4. One may recall for example the enamelled plaquettes forming part of the decoration of the chasse from Ambazac, made between 1180 and 1190 and formerly in the treasury at Grandmont; see TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm , 1996, no. 55, pp. 208-212.

CHASSE SIDE WITH VERMICULÉ GROUND:

AN APOSTLE

Limoges, circa 1185-1195

Copper: chased, engraved; champlevé enamel ; traces of gilding Height 4 13/16 in. (12.2 cm), width 2 13/16 in. (7.2 cm)

PROVENANCE

Alex Brunet collection (Angers).

LITERATURE

Brunet, A., “Émaux de Limoges dans une collections angevine”, Bulletin de la Société Archéologique et historique du Limousin, vol. CXXI, 1993, pp. 154-155.

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É. and GaBorit-ChoPin D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II, L’apogée 1190-1215, Paris, 2011, VIII B, no. 1.

This figure of a haloed apostle holding a scroll in his left hand is set against a reserved and once gilded ground engraved with a vermiculated pattern. He stands between two columns of variegated marble that support an arch topped by a turret with small openings, and wears a pale green, yellow-lined robe under a blue mantle. His face is defined in reserve, with features accentuated by dark enamelling.

While this chasse end can be associated with several others – either isolated pieces or still forming part of their original chasses – attributed to the so-called “Queyroix workshop” in the years 1180-1185, 1 it seems especially connected with a group of small chasses datable to the period 1185-1195. These later ones generally have an image of Christ in majesty on the principal side, and are marked by stylised drapery built up by short, curved lines, referred to as “drapés toriques” by Marie-Madeleine Gauthier. 2 This group, directly derived from the most significant chasses with a vermiculé background dating from between 1175 and 1185, 3 includes the small chasse with Christ in Majesty in the Musée du Louvre. 4 Apart from the similar stylisation of drapery, this work and the piece presented here share the same range of enamelled colours, the marbling effects of the columns, as well as the taste for white dots on the lapis blue enamel that enhance the orphreys on the collar and lower robe of our saint.

2.

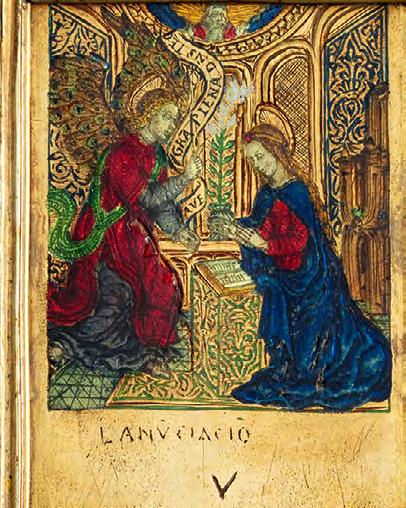

BOOK-COVER: THE CRUCIFIXION

Limoges, circa 1190-1200

Copper: engraved, chased and gilt; champlevé enamel

Height 9 5/8 in. (24.6 cm), width 5 3/8 in. (13.6 cm)

PROVENANCE

Nodet collection (Paris) in 1936.

LITERATURE

DesCheemaeker, B., “Une plaque de reliure limousine avec la Crucifixion attribuable au maître « aux asters ciselés »”, Bulletin de la Société archéologique et historique du Limousin, CXXVII, 1999, pp. 115-123.

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É. and GaBorit-ChoPin, D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II, L’apogée 1190-1215, Paris, 2011, V B, no. 2.

This plaque, originally attached to a wooden board and set within a framing frieze, was made to cover the front of a bound manuscript. It may have had a pendant plaque of the same size with an image of Christ in Majesty, but given that far fewer plaques of that subject have come down to us, we should perhaps imagine that certain bindings were composed of only one enamelled figurative plaque representing the Crucifixion.1

Set against a dark blue background punctuated with rosettes and chased asters, and crossed by three horizontal turquoise bands, the green enamelled cross bears a reserved and gilded figure of Christ. At the foot of the cross, his hands joined together, Adam emerges from a sarcophagus adorned with enamelled lozenges. To each side of the cross, standing on mounds formed of overlapping layers of flames, Saint John the Evangelist holds the Scriptures and the Virgin Mary clutches her wrist in a gesture of pain. Above the arms of the cross, a pair of three-quarter-length angels emerge from clouds encompassed by semi-circles. At the very top of the plaque, above the titulus crucis with the inscription “IHS / XPS”, appears the hand of God.

In general terms, the work holds a place in the group of book-binding plaques stylistically defined by the language of late Romanesque Limoges Work. Yet it differs from most other pieces of this kind in a number of refinements and original features. For example, we may note the use of a relatively rare colour, more typically found in early examples of Limoges Work, namely the translucent wine-red tonality whose presence is here limited to the suppedaneum (Christ’s footrest) and the thin band that suggests the interior of Adam’s sarcophagus. 2 Apart from the presence of this special colour and the beautiful radiance of the enamels, throughout, we

Book-cover: The Crucifixion

Zurich, Schweizerisches Landesmuseum.

Book-cover: The Crucifixion

Formerly Berlin, Staatliche MuseenKunstgewerbemuseum (untraced since 1945).

should underline the quality of the classicizing appliqué heads, the deep and refined chasing of the reserved areas of metal, and the delicate stippling that enlivens the contour of the plaque, as well as the reserved lines around the rosettes, the three horizontal turquoise bands and the flame motifs of the mounds.

Furthermore, the peculiar style of the drapery design, the individualization of the appliqué heads and certain details, especially in the iconography, enable us to recognize the hallmark of a specific group of binding plaques, of which two others with images of the Crucifixion have come down to us, one in the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum, Zurich, 3 and the other, even closer in appearance, once housed in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin. 4

The three plaques, of comparable size and with similar contours, closely resemble each other in style, particularly in the quality of the engraving and the treatment of drapery reflect the same manner. Draperies are marked by an arrangement of chevron-like folds, and each of the three plaques display the same original design of the Virgin’s dress, with the figure swelling out at the elbows. Likewise, a detail – the specific shape of the folds at the bottom of Saint John’s robe – recurs identically on the plaque formerly in Berlin.

If – as Danielle Gaborit-Chopin has rightly pointed out – the flared terminals of the cross are not a distinctive element of our work, 5 there is an unusual detail visible on all three of these plaques, namely the depiction of the dextera domini showing the flat part of the hand rather than the palm.

Notwithstanding due reservations concerning possible overlaps between one Limousin book-cover artist or workshop and another, 6 the proximity of the Zurich and Berlin plaques to the present piece, formerly in the Nodet collection, and the specificity of these three examples could help us recognize them as the product of the same workshop, whose achievements – each of very high quality – would date to about 1190-1200.

1. G authier, 1967, p. 155; TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm 1995, p. 170.

2. The tone is obtained by applying flux (colourless enamel) on the red copper, which thus lets the layer of cuprite that forms during crafting show through.

3. G authier, A ntoine and G aBorit-Cho Pin , 2011, VB, no. 51.

4. Ibidem, VB, no. 5. Unfortunately, this plaque disappeared from the museum in 1945 and is only known through black and white photographs, which limits comparisons with the plaque formerly in the Nodet collection discussed here.

5. G authier, A ntoine and G aBorit-Cho Pin , 2011, VB, no. 2.

6. Ibidem, p. 209.

RELIQUARY CHASSE WITH APOSTLES

Limoges, circa 1190-1200

Copper: chased and gilt; champlevé

PROVENANCE

Joseph Homberg collection (sale, London Sotheby’s, 19 July 1949, lot 156); Georges Dormeuil collection.

LITERATURE

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É and GaBorit-ChoPin, D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II, L’apogée 1190-1215, Paris, 2011, I E 4, no. 24.

The front face of this reliquary chasse bears the same general composition on the case and roof: a row of three mandorlas joined horizontally by engraved rosettes, each enclosing the figure of a saint or apostle seated on a golden arc, their feet resting on a dotted turquoise band. The deeply engraved reserved gilt figures on the front and gable ends have classicizing heads in half relief.

The great simplicity of the iconography does not preclude an appreciation of the superb quality of this chasse, the subtlety of its decoration and colours, as well as the true originality of the ornamental language. Indeed, as Simone Caudron1 has pointed out, this reliquary chasse has certain motifs which are rather uncommon among Limoges chasses, such as the blue and white cloud forms that surround the row of plaques on the principal face, or the green bands that cross the gable ends. The ends themselves show an equally original approach in the grand, slender standing figures of saints, their appliqué heads standing out from very large haloes, simply reserved and gilt. The fine reserved foliate motifs accompanying these figures are also unusual. Likewise, the back of the chasse has an original form of decoration, with quatrefoils enamelled in pale blue and white, inscribed within gilt discs set in a network of squares connected by green-enamelled dots in the interstices.

This manner of organizing the decoration recurs on the very fine chasse formerly in the collection of J. Pierpont Morgan now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2 This belongs to a small group of chasses containing certain features that rarely occur in the decorative repertory of Limoges, and

which have been dated to between 1185 and 1200. A notable piece which can be associated with this group is the chasse formerly in the Durand collection, now housed in the Musée du Louvre, 3 where foliage accompanies the figures of standing saints. Notwithstanding the parallels one could draw with the chasses in this group it seems hard to make a connection with the chasse formerly in the Dormeuil collection, which probably belongs to a slightly later period, around 1200. That being said, the present reliquary chasse seems to fit perfectly in the wake of that group, and bears witness to the significant variants and original creative exploration made by Limousin workshops in the years before they evolved into a more streamlined output.

APPLIQUÉ FIGURE OF THE CRUCIFIED CHRIST

Limoges, circa 1195-1200

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel; glass cabochons and enamel beads

[Modern right arm]

Height 10 1/8 in. (25.8 cm)

PROVENANCE

Oettingen-Wallerstein collection (Schloss Harburg).

Christ is represented in glory, alive, his eyes wide open. He appears as a sovereign, with a high crown originally embellished with cabochons (now lost) and turquoise enamel beads. He wears a blue enamelled loincloth adorned with a sumptuous gem-studded orphrey.

Another enamelled orphrey encircles his neck, though it seems unrealistic as it is not set against fabric, thus recalling a decorative element of ornamentation found in figures of Christ robed in a long tunic, such as the one formerly in the Martin Le Roy collection and now in the Musée du Louvre. 1

The somewhat heavily built and highly expressive face, the strictly frontal figure, the rectilinear treatment of the loincloth are all purely Romanesque in character. These aspects, as well as the figure’s size and the quality of its execution, enable us to associate the present object with a small group of appliqué figures of Christ with the same features. Within this group, the Christ in the National Museum, Stockholm, from the church in Ukna, 2 which is still attached to its original cross, allows us to imagine the impact of this type of monumental cross of the twelfth or early thirteenth century. We may add that the present figure of Christ on the cross clearly appears as the most elegantly executed with respect to cover plaques or to other appliqué figures.

Setting aside the Christ in the Musée Dobrée in Nantes, 3 which differs somewhat from the other examples in this group, notably in the absence of the orphrey around the neck, the three other known comparisons, such as that in the former Oettingen-Wallerstein collection, have been forcibly removed from their supports. These are the figures of Christ formerly in the Mège collection, now in the Louvre, 4 the one in the Walters Art

Museum in Baltimore, 5 and that formerly in the Boy collection and now in the Toledo Museum of Art. 6 The defining features of this group of appliqué figures of Christ include sizeable dimensions, a frontal and somewhat robust appearance, the presence of an orphrey around the neck, a loincloth with a rectilinear design, and the upper legs somewhat drawn up.7

Although it is not the largest in the group, the Christ formerly in the Oettingen-Wallerstein collection may be considered one of the most beautiful, to judge by the quality of its execution. Notable here is the quality of the enamelling and chasing, for instance in the elegant treatment of beard and hair, with a few locks attentively defined. Likewise, the two small enamelled loincloth folds, where the fabric overlaps the orphrey, and the folds formed by the orphrey between Christ’s knees, add further refinement.

Only the figure in the Louvre, especially owing to the deeper chasing of the torso and the vermiculé motifs adorning the orphrey of the loincloth, appears to be superior to the Christ presented here. However, we may note that our figure offers a slightly more Romanesque character with respect to the one in the Louvre, in particular because of its strict frontality, the sensitive modelling of the face and torso, and the elongation of legs and feet.

These last elements, as well as the chromatic range of the enamel, allow for a slightly earlier placement in time than the piece formerly in the Mège collection, which Élisabeth Taburet-Delahaye had proposed was executed between 1195 and 1210; we would thus plausibly situate our Christ in the decade 1190-1200.

1. Inv. OA 8102. See TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm , 1996, pp. 184-185, no. 49.

2. A ndersson , 1980, pp. 18-22, fig. 32.

3. Inv. 896-1-24.

4. TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm , 1996, pp. 186-187, no. 50.

5. A ndersson , 1980, fig. 34.

6. Catalogue des Objets d’Art et de Haute curiosité de l’Antiquité, du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance composant la collection de feu M. Boy, Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 15-24 May 1905, pp. 28-29, lot 151.

7. As regards the Christ presented here, we should note that the legs are attached and fixed under the loincloth, in the same way as on the monumental figures of Christ in the Auvergne. Having been unable to study the reverse of the other figures in this group, it seems difficult to assert that these are constructed in the same manner; however, since the legs also appear to be drawn up, it is more than likely that these were mounted with the same technique.

CHASSE (RELIQUARY CASKET) WITH THE CRUCIFIXION AND CHRIST IN MAJESTY SURROUNDED BY APOSTLES

Limoges, circa 1195-1200

Champlevé enamel on copper gilt

Heigt 6 15/ 16 in. (17.6 cm), width 8 ½ in. (21.7 cm), depth 3 5/ 16 in. (8.4 cm)

PROVENANCE

The chasse is said to have been found in the nineteenth century, walled up in a village in the Basque Country.1

LITERATURE

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É. and GaBorit-ChoPin, D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II , L’apogée

1190-1215, Paris, 2011, I B 1, no. 43.

The simple and massive forms of Limoges chasses are those of so-called “house-shaped” reliquaries generally found in Western art during the Medieval period until the beginning of the thirteenth century: a rectangular casket resting on straight feet, with a gabled roof usually surmounted by a ridge that has most often gone missing, as in the example studied here. While Limoges workshops did not revolutionise the forms of reliquaries, they nonetheless crafted an economic change that explains the extraordinary success of Limousin Work throughout Western Europe. The use of gilt copper enhanced by vivid enamel colouring, and especially this kind of almost unreal background, made of lapis lazuli blue, offered a result – at a modest price– that was just as striking and perhaps even more enticing than works using precious metal, enriched by gemstones to contribute to their colour.

On the main side of the casket, the crucified Christ, dressed in a perizoneum (loincloth) stands out against a bold green Cross. Below his arms stand the Virgin Mary, her hands tightly clasped in sorrow, and Saint John the Evangelist with his right hand against his cheek. On either side of this principal scenes, an Apostle is enthroned within an elongated four-lobed shape, the first blessing and the second holding the Book of Scriptures. Both are represented in a manner that recalls that of Christ in Majesty, seated on the golden arc of a rainbow, with feet resting on a turquoise enamelled footstool, and one even finds the motif of the orphrey of their mantle forming the outline of a knee pad-like shape on their right leg, following an iconography already found in Limoges manuscript illumination at the end of the eleventh century and the beginning of the twelfth. 2 On the roof, placed centrally, Christ sits enthroned in Majesty within a mandorla, standing out against a midnight-blue ground strewn with small enamelled rosettes. He holds the Book on his knee and blesses with his right hand. His long fingers extend beyond the reserved gilded framing of the mandorla. Flanking him, two pairs of Saints – no doubt Apostles – stand under round arches supported by capitals, with small turrets emerging from them.

Likewise, on each end of the casket, two Apostles, simply incised against an enamel ground crossed by a double band of turquoise, stand under a round arch surmounted by a small bell-tower. The back of the casket is embellished with a traditional field of enamelled rose-patterned motifs.

This iconography – with the figure of Christ dead on the Cross and a Christ in Majesty in a mandorla, surrounded by Apostles – was already widespread among chasses with vermiculé backgrounds of the preceding period. Its non-specific character corresponds perfectly of the needs of an increasingly expanding client base, becoming very frequent in works of various size and quality at the beginning of the thirteenth century.

The decoration and style of this chasse are still entirely associated with Limoges work of the Romanesque period. The figures on the principal side, crafted in reserve and engraved, all have “Classical” appliqué heads, and the relatively restrained palette of the enamels is embellished by a subtle alternation of medium blue and deep ultramarine. As well as the quality of the chasing in the engraved figures, one may note the sophistication of the fine stippling, which brightens all the reserved and gilded areas3 and contribute to making this reliquary chasse a very fine example of work from the Limoges workshops in the period 1195-1200.

1. At that time, it contained some remains: see G authier, A ntoine and G aBoritCho Pin , 2011, I B 1, no. 43.

2. For example, in the Sacramentary of Saint-Étienne in Limoges, or the Rule of Saint Benedict from Saint-Martial: see Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ms. lat. 5243, fol. 45v and ms. lat. 9438, fol. 58v.

AN APPLIQUÉ FIGURE OF CHRIST

Limoges, circa 1195-1210

Copper: repoussé, engraved and gilt; champlevé enamel; glass cabochons and enamel beads

Height 8 1/8 in. (20.6 cm), width 5 3/8 in. (13.7 cm)

Christ is represented in glory, alive, his eyes wide open and wearing a high enamelled crown embellished with turquoise beads. He is dressed in a blue-enamelled perizoneum enriched with glass and enamel beads, and has an enamelled band, similarly decorated with glass beads, around his neck. As on the appliqué figure of Christ formerly in the OettingenWallerstein collection (cat. no. 11), the band thus seems to recall residual ornamentation of the kind found on figures of Christ clothed with a long tunic, produced a little earlier, such as the Christ formerly in the Martin Le Roy collection, now in the Musée du Louvre.1

Here, the strictly frontal pose of the figure, the rigid and rectilinear treatment of the perizoneum, and the lengthening of the legs, set back from it, all communicate a fully Romanesque style. In any case, these various characteristics, as well as the presence of the enamelled orphrey on the neckline, allow us to connect this Christ to a group of large-scale appliqué figures of Christ associated with the work housed in the Swedish History Museum, Stockholm, from the church in Ukna, which remains attached to its original Cross. 2 Key items in this group include the great Christ formerly in the Mège collection, in the Louvre, 3 the one in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, 4 the one formerly in the Boy collection, now in the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio,5 and the one formerly in the Oettingen-Wallerstein collection mentioned above.

Even if the Christ presented here is smaller than these examples and reflects a somewhat less vigorous style, the absence of softening in the figure and its still entirely Romanesque character support our view of it as entirely contemporary with these grand appliqué figures of Christ assembled around the Ukna Cross, that is, from the years between about 1195 and 1210. In this respect, our appliqué Christ constitutes a further and very fine example of enamelled relief produced by the Limoges workshops around the turn of the thirteenth century.

1. TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm , 1996, pp. 184-185, no. 49.

2. A ndersson , 1980, pp. 18-22, figs. 32-33.

3. TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm , 1996, pp. 186-187, no. 50.

4. A ndersson , 1980, fig. 34.

5. See Catalogue des Objets d’Art et de Haute Curiosité de l’Antiquité, du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance composant la collection de feu M. Boy

Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 15th-24th of May 1905, pp. 28-29, no. 151.

BOOK-COVER PLAQUE: THE CRUCIFIXION

Limoges, circa 1200

Copper: engraved, chased and gilt; champlevé enamel Height 9 5/ 16 in. (23.6 cm), width 4 5/ 16 in. (11 cm)

LITERATURE

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É. and GaBorit-ChoPin, D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II, L’apogée, 1190-1215, Paris, 2011, V C, no. 5.

This plaque was the central part of the upper board of a manuscript binding. The design is strewn with enamelled rosettes and crossed by a single horizontal turquoise band. The figure of Christ is nailed to a Cross enamelled in green, the symbolic colour of resurrection, and his feet are supported by a broad light blue suppedaneum adorned with red-dotted white discs. The Virgin Mary and Saint John, placed on either side of the Cross, stand over an imbricated pattern (a group of overlapping scales), as does Adam, the small figure emerging from a sarcophagus enamelled in diagonal patterns. Above the arms of the Cross, two Angels with wings spread appear in three-quarter length behind two semi-circles embellished with a multi-lobed cloud pattern. Set in a cruciform halo, the hand of God comes out of an undulating cloud above the titulus bearing the monogram of Christ, IHS.

All the figures, reserved and engraved, have beautiful appliqué heads of the classic type. Only the appliqué figure of Christ is entirely repoussé, chased and gilded.

The upper and lower borders are adorned by an undulated, threelobed and stippled motif. Likewise, the entire contour of the plaque is outlined with undulation and stippling.

Stylistically, this plaque with the Crucifixion may be compared to the central plaque of the book- cover formerly in the Seguin collection, now in the Musée du Louvre.1 In fact certain very similar details recur on each plaque, such as Adam’s sarcophagus, Christ’s suppedaneum and the composition of the imbrication.

The substantial amount of stippling in the reserved areas, the quality of the modelling in the figure of Christ and in the appliqué heads, the depth of the chasing, and the beautiful smoothing of the enamel, make this plaque a very fine example of “classic” Limousin work of the years around 1200.

CIRCULAR PLAQUE: CHRIST IN MAJESTY

Limoges, circa 1200

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel

Diameter: 2 ½ in. (6.5 cm)

The dimensions of this small circular plaque, as well as its iconography, make it possible to determine that it came from the central junction of the reverse of a large processional cross.

The figure of Christ in Majesty is seated on a broad enamelled cushion set on an elaborate throne with alternating reserved and enamelled areas. He raises his right hand in blessing and holds the Book of Scriptures in his left hand, on his knee. His enamelled cruciform halo is flanked by the Alpha and Omega, reserved and gilded. The deep blue enamel ground is strewn with reserved and gilded dots and enamelled rosettes.

Notwithstanding the damage suffered by the plaque, probably as the result of intense heat, one can still appreciate the great quality of the craftsmanship in the engraving of Christ’s robe, the fine enhanced dotting in the reserved areas, and above all the beautiful appliqué head. These various elements allow us to date this small medallion to the peak period of Limoges Work, around the year 1200.

RELIQUARY CASKET: THE CRUCIFIXION AND CHRIST IN MAJESTY

Limoges, circa 1200-1210

Copper: engraved, chased and gilt; champlevé enamel Height 7 11/16 in. (19.5 cm), width 7 1/16 in. (18 cm.), depth 3 3/8 in. (8.5 cm) [Modern crest]

PROVENANCE

Marynen collection (Brussels, 1888); Charles Testart collection (sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 24-25 June 1924, lot 80, pl. VIII); Octave Pincot collection (sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 25 November 1946, lot 46, pl. XV1); Baron de Bonstetten collection (sale, London, Sotheby’s, 10 June 1969, lot 23).

EXHIBITION

Brussels, Exposition rétrospective d’art industriel, 1888.

LITERATURE

Reusens, E. H. J. (ed.), Exposition rétrospective d’art industriel à Bruxelles, Brussels, 1888, no. 63.

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É. and GaBorit-ChoPin, D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II, L’Apogée, 1190-1215, Paris, 2011, I B 1, no. 26.

This chasse has the classic form of “house”-shaped reliquaries generally found in Western European Medieval art until the beginning of the thirteenth century: a rectangular casket resting on straight feet, topped by a double-pitched roof surmounted by a crest. Here, the hinged roof forms the opening lid of the reliquary, following a model that was not so common in the corpus of Limoges reliquaries.

The centre of the main panel of the chasse, on the principal face, shows the crucified Christ, dressed in a loincloth and set against a green-enamelled cross, topped by a golden titulus crucis . Two bust-length angels appear above the arms of the cross, and below these stand Saint John and the Virgin Mary. The crowned Virgin tenses her wrist in a gesture of pain. Flanking this main scene, an apostle or saint stands under a semi-circular arch that rests on slender columns, which in turn support little turrets. On the roof, in the middle, the figure of Christ in Majesty is enthroned within a reserved gilded mandorla decorated with stippling. He holds the Book of Scriptures in his left hand and blesses with his right. Around the mandorla are the heads of the four symbols of the Evangelists: Saint Luke’s bull, Saint Mark’s lion, Saint Matthew’s male figure, and Saint John’s eagle. We may note that here, contrary to custom, the small appliqué head of an eagle, normally used to symbolise John the Evangelist, has given way to a man’s head of the type used for Matthew. Saint John is nevertheless clearly identifiable by his elongated, feathered neck. It was not uncommon in Limousin art for goldsmiths to use available appliqué heads, without being concerned about their perfect suitability to the body on which they were placed. 2

On either side of Christ in Majesty, framed by the symbols of the Evangelists, a saint or apostle stands under a semi-circular arch, following the same composition as on the body of the casket.

On the principal face, on the body as well as on the roof, the figures –each fitted with small appliqué heads – stand out against a medium blue

background, crossed from one side to the other by a turquoise band and strewn with multicoloured discs and rosettes.

The end sides have an original decoration consisting of a turquoise medallion enclosing an engraved angel with outstretched wings, emerging half-length from polychrome clouds. The gable is decorated with a disc containing an enamelled floral motif with five petals on a turquoise background. Three stems emerge from the medallion, forming golden foliage that fills the spandrels.

The reverse of the chasse is covered by a network of lozenges with reserved, finely-stippled contours, containing a uniform series of champlevé rosettes on the roof and small quatrefoils on the body, alternately coloured, in blue and white or green and yellow, around a red centre.

The concept of a lidded roof, the half-length angels inscribed in medallions on the sides and the expansive scattering of enamelled rosettes on a medium blue ground on the front face, are all elements that can be found on two very beautiful reliquary chasses dedicated to the childhood of Christ, housed respectively in the Louvre and the British Museum, and dated to the period 1190-1210. 3

With respect to these two chasses, the one formerly in the Pincot collection, which is smaller, shows less refinement in the tooling of the figures and the design of their contours. Its non-specific iconography corresponded perfectly to the needs of an ever-expanding clientele and appeared frequently on works of varied size and quality from the beginning of the thirteenth century onwards.

Chasse of the Holy Innocents , Limoges, circa 1190-1210. Paris, musée du Louvre.

Chasse of the Adoration of the Magi , Limoges, circa 1200. London, The British Museum.

1. The reference in the catalogue of the Pincot sale to a provenance from the “Collection R. 1924” as Léonce Rosenberg sale of 12-13 June 1924 is erroneous; this in fact refers to the sale of the Testart collection, which also took place at the Hôtel Drouot, but on 24-25 June 1924.

2. See for example TaB uret-D elahaye and D rake B oehm , 1996, no. 73, p. 257.

3. For the chasse in the Musée du Louvre (OA 10406), see ibidem, no. 41, pp. 168-169; and G authier, A ntoine and G aBorit-Cho Pin , 2011, I E 4, no. 19. For the one in the British Museum, ibidem, IA 2, no. 10.

BASE FOR A CROSS

Limoges, circa 1200-1210

Copper: gilt, champlevé enamel

Height 4¼ in. (10.8 cm), width 4 in. (10.2 cm)

PROVENANCE

Princely Collection of Liechtenstein (Vaduz) 1932; E. and M. KoflerTruniger collection (Lucerne); Keir collection

EXHIBITED

ZuriCh Sammlung E. und M. KoflerTruniger, Luzern, Kunsthaus, June 7th - August 2nd 1964.

AaChen , Mittelalterliche Elfenbeinund Emailkunst aus der Sammlung

E. und M. Kofler-Truniger, Luzern, Suermont Museum,1965.

Kansas City, The Keir Collection, Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, 1983.

LITERATURE

SChnitzler, H., BloCh, P. and Ratton, C., Email, Goldschmiedeund Metallarbeiten, Europäisches Mittelalter, Sammlung E. und M. Kofler-Truniger, Luzern, II, Lucerne and Stuttgart, 1965, no. E112, pl. 57.

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É. and GaBorit-ChoPin, D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II, L’apogée 1190-1215, Paris, 2011, VII B II-2 A, no. 15.

This base consists of a truncated three-sided pyramid form supported by three feet each surmounted by an engraved mask of a monster. The three facets of the base are each adorned with a circular medallion with a reserved gilt border, surrounded by a lapis blue enamelled ground. A reserved foliate motif extends across each side of the medallions, its elegant tendrils enclosing a floral motif with three tones of enamel: red, green and yellow. The centre of each medallion is enamelled in pale blue and contains a small monstrous creature, reserved and gilt. This two-legged winged animal has a canine head, a lion’s bust and a tail ending in a vegetal motif.

The pyramidal base supports a shaft decorated with engraved scales and topped by a knop enamelled in blue and adorned with reserved gilt foliate motifs.

This crossfoot has exactly the same structure as candlesticks created in Limoges Work during the same period, and was recently published as an incomplete candlestick.1

Nevertheless, the rectangular opening visible above the knop makes it possible to ascertain that it is actually a foot of a cross. The piece was also described as such when it was in the Kofler-Truniger and then Keir collections. 2

This type of base was made to secure a grand cross and thus allow it to be presented on an altar. It should be pointed out that crosses with their original bases are rare; examples include the cross in the Diocesan Museum of Freising in Bavaria, 3 datable to about 1190, and the one in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow, 4 which dates from about 1200 and has a base closely resembling the one studied here. In the present piece, the high quality of the drawing of the rinceaux, delicately crafted in pointillist detail, as well as the beautiful dotting of the enamel, also suggest it dates to the period between 1200 and 1210.

CROSS

Limoges, circa 1200-1210

Copper: traces of gilding; champlevé enamel Height 7 1/4 in. (18.5 cm)

PROVENANCE

Octave Pincot collection (sale, Paris, 25 November 1946, lot 20); Carlos A. Zemborain collection (Buenos Aires), 1965; José Léon Aldao collection (Buenos Aires), 1971.

LITERATURE

ThoBy, P., Les croix limousines de la fin du XIIe siècle et du début du XIIIe siècle, Paris 1953, p. 155, no. 109.

François, G., “Répertoire typologique des croix de l’Œuvre de Limoges, 1190- 1215”, Bulletin de la Société archéologique et historique du Limousin, CXXI, 1993, p. 110.

This solid copper cross has a round central junction, flared ends, and a triangular tenon at its base.

On the obverse, the figure of the crucified Christ, reserved and engraved, has a Classicizing appliqué head in relief. Above the figure, the inscription “IHS. XPS.” is engraved in reserve on two lines, on a green enamelled background. At the top of the cross, engraved in reserve, the Dextera Domini (right hand of the Almighty) extends down towards Christ. At the base, under the green enamelled suppedaneum (foot-support), the resurrected Adam is represented with a contoured body engraved in reserve and a head added in half relief. The arms of the cross, enamelled in deep blue, are covered in foliate motifs with areas reserved for polychrome fleurons.

On the reverse, the Lamb of God, depicted laterally, is inscribed within the circular medallion at the junction of the cross. Engraved foliage derived from the vermiculated type spread across its arms.

The modest dimensions of the cross, as well as the presence of the pointed tenon at its base, suggest that it was made for an altar, secured in a removable foot of the type seen in the piece formerly in the Kofler-Truniger collection (cat. no. 18).

PLAQUE: CHRIST IN MAJESTY IN A MANDORLA

Limoges, circa 1200-1220

Copper: traces of gilding; champlevé enamel

Height 4 1/4 in. (10.7 cm), width 3 in. (7.5 cm)

This plaque in the shape of a mandorla comes from the central junction of the reverse of a large processional cross with trefoil extremities – the type of cross that was most widespread between the end of the twelfth and beginning of the thirteenth centuries.

In the centre, the half-length figure of Christ in Majesty emerges from an enamelled cloud. He holds the Book of Scriptures in his left hand and blesses with his right. The classicizing appliqué head, framed within an enamelled cruciform halo, is flanked on one side and the other by the Alpha and Omega. The deep blue enamelled ground is strewn with rosettes and enamelled disc motifs.

The significant wear of the gilt surface and losses in the enamel in no way impede us from appreciating the refined design of the engraving and attentive chasing. These elements, as well as the classical-style appliqué head and the palette of the enamelling, would indicate a date of execution in the period between 1200 and 1220.

CANDLESTICK BASE

Limoges, circa 1200-1220

Copper: gilt; champlevé enamel

Height 3 in. (7.5 cm), width 3 ½ in. (8.8 cm)

This candlestick base in the shape of a curved cone is embellished with enamelled foliate and flower scrollwork motifs that stand out against a lapis blue enamelled background. Its summit is covered with a pattern of engraved scales. A long two-headed animal is riveted to the upper part of each of the three legs. This creature of fantasy, an amphisbaena , consists of a lion’s face topped by small horns, a lizard’s body, and a long tail ending in the form of a snake head. Originally, the eyes of each of these creatures were made of glass beads and their bodies were adorned with three turquoise enamel beads.

The conical shape of this base, its enamel decoration, and the presence of the three fantastic animals on the feet, all offer points of comparison with the two large candlesticks from the church of Øster Jølby in the National Museum, Stockholm. 1 Of a truly exceptional type among Limoges candlesticks, the pair in Stockholm, datable to about 1200, are only comparable with two other pairs of candlesticks, of relatively similar though simpler composition, both housed in Trondheim, in the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. 2 The latter, datable to about 1200-1220, must also have originally included three fantastic appliqué animals on the feet.

The parallels between the base studied here and these three pairs of candlesticks enables us to propose with a good degree of confidence that it also have functioned as the base of a candlestick of a similar type.

We can draw another relatively close parallel with a work that can also be dated to the first quarter of the thirteenth century in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. 3 It consists of a circular base topped by a series of engraved scales, and bearing three fantastic appliqué animals of the same type. There, the inscription along each side of the enamelled band indicates that the base served as the foot of a reliquary. 1. See LieBGott, 1986, p. 62, no.

BOOK-COVER PLAQUE: THE CRUCIFIXION

Limoges, circa 1210

Copper: engraved, chased and gilt; champlevé enamel Height 9 in. (22.9 cm), width 4 5/16 in. (11 cm)

PROVENANCE

Léon Arnault collection

LITERATURE

Gauthier, M.-M., Antoine, É. and GaBorit-ChoPin, D. (eds.), Corpus des émaux méridionaux, II, L’apogée 1190-1215, Paris, 2011, V C, no. 62.

The plaque is strewn with enamelled rosettes and reserved dots, and is crossed by a horizontal band of turquoise, outlined by two thin bands of light blue that stand out against the dark blue ground. The basic design is repeated on the cross, enamelled in green – the colour symbolic of resurrection – which appears almost overlaid on a second, larger cross in light blue and which supports the titulus crucis with the inscription “XPS/ IHS.” Under the arms of the cross another band bears the inscription “SCA MARIA / SCE [sic] IOH[ann]ES”, thus identifying the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist in a fairly unusual way; a variant of this appears on the binding plaque formerly in the Salmon collection.1