5 minute read

Virtual learning – moving forward

Usman Ahmed

Advertisement

Usman Ahmed is a Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon with a special interest in Lower Limb Revision Arthroplasty at the Princess Royal Hospital, Telford. He is Head of Virtual Learning for Health Education West Midlands. COVID-19 has brought about carnage that has tested our profession, our patients and our communities to limits we never knew we had. As the first wave reared its head, we didn’t just witness the acute and profound impact on healthcare of COVID-19 but also the fallout and consequences on all other aspects of the NHS and society.

As clinicians up and down the nation mobilised to serve the NHS, one area that was severely hit was training. Yet as we know, necessity is the mother of all inventions, and with that the pre-COVID dabbling in virtual learning suddenly became a collective commitment to put together something, anything, to allow ongoing teaching.

Surgical training in particular was hit by COVID-19 with more cautious consultant led emergency surgery and a complete halt to elective work, which in orthopaedics is often more significant than other specialties. Virtual learning is not new. Globally universities, schools, public organisations and private companies have developed or acquired platforms to facilitate online learning. The odds are that you’ve probably participated in it without even knowing as many mandatory training modules are on such platforms.

But this pandemic is probably the first time that the spotlight has been shone brightly on the role of virtual learning in postgraduate medical education, and a plethora of new terminology is being thrown around with more gusto than ever before.

Where to begin?

There are a variety of platforms available that can be utilised for education.

Multiple specialty websites exist such as Orthobullets© and Radiopedia© which are phenomenal collaborative resources. The quality of the freely available information is such that it is a wonder that anyone ever needs to buy any books! But these can lose their sheen as the ability to engage users with the information beyond reading it and doing quizzes can be limited.

Twitter® (a microblogging site) has been growing in popularity with clinicians and there are small pockets of clinicians having positive and educational discourse online. But there is no formal quality assurance and like all social media should be acknowledged to be a completely public platform, and not always for the purpose of education1. The same applies to YouTube® , however it does provide the opportunity for educators to easily and economically upload high quality content for dissemination.

Then there is the role of video conferencing and webinars. With some companies offering free or heavily discounted subscriptions, Orthohub2 is one example of an educational programme that has risen up from a local audience to an internationally recognised platform providing high-quality webinars from recognised specialists. The engaging nature of the webinars, which are also available for review on the website, is one aspect of many that is fuelling the new culture of flexible online learning. However, watching a video after the live event often lacks the real-time charm which is more engaging.

Teaching and training comes with administrative needs. Educators in formal roles have to assess how to not only deliver the content but also optimise it and appropriately administer it. And this is where we can learn from schools and universities who utilise Learning Management Systems (LMS) such as Moodle™ and Canvas. The LMS platforms offer the ability to deliver content in many different and flexible ways whilst providing data on user activity and engagement tracking. The ability to build an entire school online, develop areas for specific specialties, collate and curate resources, record attendance and feedback, and exploit built in web-conferencing platforms means that the possibilities are endless.

This then allows more focus on the human element of virtual learning. Acknowledging the heterogeneity of every group of trainers and teachers is complicated by technological capabilities and facilities. Therefore, there is a tremendous emphasis in engaging all groups to not just participate but to change well-established habits of teaching/learning to adapt to the new normal. Culture change can be incredibly slow and requires patience and persistence.

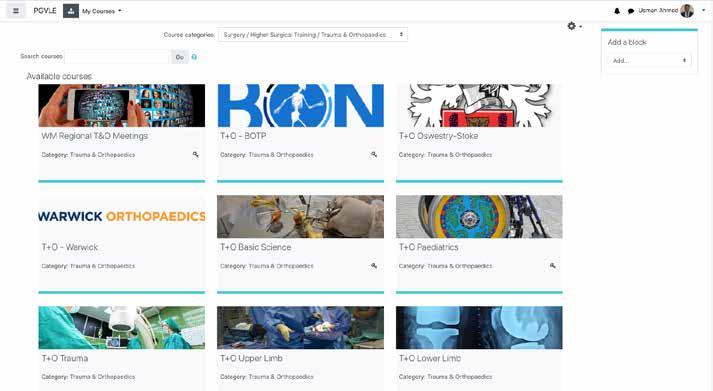

Recognising that regular structured teaching programmes needs to have administrative back-up led to the development of a Moodle/ BigBlueButton based platform which has now expanded beyond orthopaedic borders. The HEEWM supported PGVLE3 initially starting as an online school for surgical training but organic growth has led to it now facilitating medical and psychiatric programmes in the region.

Programmes traditionally reliant on regular face to face teaching days now have access to an entire virtual environment that is akin to moving into a partly furnished flat but with a concierge service and a relaxed landlord. The ambition of having a flexible environment that allows not only for the transfer of existing face to face programmes to the Internet, but also enough capability to allow for creativity and refinement of these programmes is being realised. In its current format the PGVLE has become the hub for teaching programmes, out of hours trainee sessions, regional meetings, administrative meetings and standalone courses.

The rise of the Digital Teaching Fellow

One strategy to drive ventures such as the PGVLE forward is to engage stakeholders by giving them ownership of the educational processes. Alongside the PGVLE we created the Digital Teaching Fellow (DTF) post where each specialty in the region has a trainee coordinating, organising and building the desired teaching environment. The DTF role works in close collaboration with training programme directors to integrate and customise the online platform in order to comfortably transition into the virtual environment without it being too disruptive to the normal teaching programme. The fact that the training programmes have the opportunity to build their programme online within a comfortable framework has led to creativity on the part of the DTFs and the expansion of shared ideas.

The result of this empowerment has been an organic trainee driven growth of the platform which has expanded beyond just surgical training and into other clinical schools.

Evolution

Almost every initiative that started with the lockdown in March 2020 has evolved, with many of them finessing their main events with both a warm-up (reading, case, resources) and a warm-down (quizzes, podcasts, consolidation sessions). This has been shaped by the participants providing honest feedback and teachers being open and receptive to it.

There is no doubt that with current variability in guidance on physical interaction that virtual learning is here to stay, and training programmes must have the capability to go either completely virtual or at least hybridise teaching easily. However, this can only happen if there is due thought and consideration given to the culture and governance of education in the real world and not just the virtual mechanism of delivery. n

References

1. Sahu MA, Goolam-Mahomed Z, Fleming S,

Ahmed U. #OrthoTwitter: social media as an educational tool. BMJ Simulation and

Technology Enhanced Learning. September 2020 [Epub ahead of print].

2. OrthoHub. Available at: www.orthohub.xyz.

3. Postgraduate Virtual Learning Environment (PGVLE). Available at: https://pgvle.co.uk.