11 minute read

The Doctor is In by Nick Sawicki

The Doctor Applications of telehealth for rural populations is In

by Nick Sawicki ’23, an Economics and Biology concentrator in the Program in Liberal Medical Education

Advertisement

illustration by Katie Fliegel ’21

For most Americans in suburban or urban areas, a trip to the doctor is usually as innocuous as a quick 20-minute car ride. But for 20 percent (60 million) of Americans who live in rural communities, where hospitals and the health care professionals needed to staff them are scarce, accessing basic medical care poses a much greater challenge.

The shortage of doctors and closure of hospitals in rural communities can be largely attributed to a generation of rising physicians who are unwilling to practice medicine in sparsely populated communities. A 2019 Merritt Hawkins survey found that only one percent of fourth year medical residents were willing to work in communities with less than 10,000 residents. As a result, 119 hospitals that once served rural communities have closed their doors since 2010, a record-breaking 18 of which closed in 2019 alone. In places such as Wheeler County, Oregon, community members have to travel over 70 miles to their nearest hospital to meet with a physician. Such an inconvenience ultimately means that these Americans often defer visits to the doctor until their medical situation becomes absolutely dire, a practice that leads to higher rates of obesity, cancer, diabetes, infant mortality, and death from preventable disease.

When Covid-19 struck in late March, forcing doctor’s offices and hospitals to admit only patients with emergency medical conditions in both rural and urban areas, the medical community was quick to take up a solution that had previously seen only limited use: telehealth. While not previously covered by Medicare or private insurance, virtual visits quickly became the norm as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services temporarily expanded coverage to include

telehealth appointments, with private insurance plans quickly following suit. Now, total telehealth visits are slated to surpass one billion in number by the end of 2020.

Although the adoption of telehealth is only meant to be a temporary solution while social distancing and other public health measures remain in effect, this shift in the healthcare delivery paradigm has incidentally increased healthcare accessibility for many segments of the population. For rural communities in particular, these virtual visits may very well be the key to breaking

down geographic barriers to healthcare by connecting patients to healthcare providers without the time commitment or costs of traveling to their nearest hospital.

Dr. Jay Zaslow of Brewster, New York is a family physician at a federally qualified health facility where 80 percent of his patients fall under the national poverty line and can’t always afford a visit to the doctor. He expressed that when a person makes “$200 a week cleaning homes” or “has to work multiple shifts at McDonalds,” they can’t always afford the $20 taxi fare to transport themselves to the doctor’s office, let alone take time off work. Virtual visits provide patients with greater flexibility to see a doctor on their own time while also avoiding unnecessary transportation costs.

When virtual visits ballooned from five percent of his visits before Covid-19 to over 95 percent of visits as infection rates peaked in New York, Dr. Zaslow concluded that for “select problems, you could absolutely replace in-person visits with virtual ones.” While we have yet to reach the point of performing, say, a virtual rectal exam, Dr. Zaslow suggested that virtual medicine can serve to “complement” more traditional, in-person visits, increasing efficiency and elevating the quality of delivery.

If telehealth can practically be used to supplement healthcare in Brewster, with a population of under 3,000, perhaps telehealth should be more seriously considered as a way to supplement the shortage of healthcare services in other rural communities. Dr. Timothy Empkie, retired Associate Dean of Medicine at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School, once practiced medicine in Linton, North Dakota, a county larger than the entire state of Rhode Island but with a population of less than 6,000 people during the 1970s. He recalls that even back then, a rudimentary “virtual” line of communication existed between the primary hospital in Bismarck, North Dakota and the county’s health clinic. This link permitted the county to erect a miniature critical care unit to treat patients with mild heart attacks and facilitated life-saving care for patients who needed immediate attention.

Dr. Empkie believes that this same concept can be applied to allow patients in rural communities to receive medical consults from specialists anywhere in the country. Patients could choose to either receive consults from the comfort of their homes or from their local generalist’s office. While there are certainly limitations to telehealth, this newfound access to healthcare for patients in rural areas may very well end up being a silver lining of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Big Brother’s Rude Awakening

How data ought to be protected in the age of the internet

by Gabe Merkel ’23, an intended Political Science concentrator and a Managing Editor at BPR

infographics by Erika Bussman ’22 and Madi Ko ’21

Americans have prized individual liberty since the nation’s founding. Naturally, many people are suspicious of the government collecting their data. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, a majority of Americans disapprove of the US government’s collection of telephone and internet data, and over 90 percent of Americans “say it is important to control who can get their information, as well as what information about them is collected.”

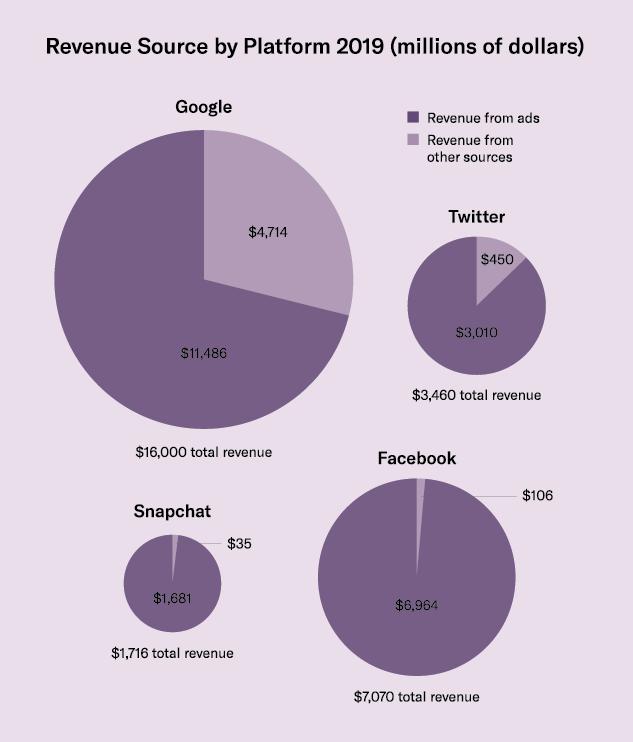

However, there is a force in American life that threatens data privacy as much as the government does: tech companies. Though Americans are concerned about tech companies’ collection of data, which can be tied to a relentless pursuit of profit, almost nothing has been done to curtail this phenomenon. Google and Facebook record every website their users go to, every photo they look at (and for how long), and much more. However, rather than storing and recalling taped phone conversations only in instances where, say, national security is threatened, as the NSA claims to do, these companies immediately put the data to work to help target ads and suggest content—a

“However, rather than storing and recalling taped phone conversations only in instances where, say, national security is threatened, as the NSA claims to do, these companies immediately put the data to work to help target ads and suggest content—a practice which has become essential to their business model and their profits.”

practice which has become essential to their business model and their profits.

Tech companies like these know more about users than most people realize, from the kind of toothpaste they use to their sexual orientation. The use of this data can easily become problematic. For example, a person who is recovering from an addiction to alcohol may get an ad for a special deal on their favorite whiskey brand or see suggested videos of celebrities having fun at a bar because they have expressed interest in alcohol in the past. Google Maps might even tell them when they are close to a liquor store. These kinds of digital suggestions and reminders are not only detrimental to a person’s recovery and wellbeing, but they compromise the consumer’s privacy.

No single entity should have this much knowledge and power, especially not trillion-dollar corporations with few obligations beyond appeasing their shareholders and maximizing their profits. With the current landscape of ineffective mediation and sparse government action, a federal “data tax” on tech companies’ collection of user data is necessary to curtail these companies’ mass data collection and protect the fundamental liberties of Americans.

A data tax is not a novel idea. Politicians, particularly from local governments, have been proposing the solution for years. Similar taxes, including severance taxes, are already in use in some states and provide a basic model for how a data tax might function. A severance tax is a tax on non-renewable resources and is most often implemented as a measure to gradually disincentivize natural gas and oil extraction. These taxes— which normally range from one to six percent of the value of the goods—generated nine billion dollars in revenue in 2017. While severance taxes were mostly created to raise state revenue, they have also slightly reduced oil and gas extraction in certain states. Economists estimate that the “elasticity of oil drilling with respect to severance taxes is between -.3 and -.4”, meaning that a “one percent increase in the severance tax rate would reduce drilling by about 0.3 to 0.4 percent.” So, while they are bad news for oil companies, severance taxes have been successful in raising revenue and slowing down the extraction of pollutive natural resources. A data tax would have a similar goal: to raise tax revenue while decreasing data collection by tech companies.

There is good reason to believe that a data tax could be even more effective at curtailing data collection than severance taxes have been for reducing drilling. First, data collection is likely to be more sensitive to changes in price compared to oil drilling, given that oil is a commodity with a relatively stable price. The value of data, on the other hand, is tougher to quantify. A data tax would force companies to carefully consider which consumer data is most valuable and only collect that, cutting back on the accumulation of other, less lucrative user information. Second, while severance taxes usually charge a flat rate for each barrel of oil or ton of coal, the data tax could operate using a tiered model. Companies should be permitted to collect some data on their users as a means of upholding their legal right to generate revenue

from consumers’ use of digital products. However, when a firm begins to collect data over a certain predetermined threshold, they would be subject to a data tax levied at a proportional rate. This taxation model would operate similarly to the progressive tax system in the US. The more data over the threshold a company collects, the more that data is taxed. Under this system, companies will be able to collect the data they need, but not all the data they want.

With billions of dollars at stake, tech giants like Google and Facebook would not accept these newly imposed taxes without a fight. Any lawmaker who proposes a data tax can expect companies to do all they can to derail the legislation. Tech companies are capable of spending massive sums on lobbying to influence politicians and impact potential legislation. Over the past decade, the seven largest tech companies in the US—including Facebook and Google—have spent over half a billion dollars on lobbying and advocacy. It is also conceivable, and even probable, that tech companies affected by the data tax would challenge its constitutionality, similar to how severance taxes have been challenged. Yet, severance taxes were still found constitutional, as a data tax might be, in the Supreme Court. Given that a data tax could meaningfully decrease these company’s profits, there is no question that they will be willing to spend as much as it takes to stomp out the idea. Aside from these challenges posed by tech companies’ inevitable resistance, there would still be implementation issues to address. Fundamentally, there is the question of how to record the amount of data being collected by companies. Should the federal government allow companies to self-report their data collection practices or does that just open the door for fraud and tax evasion? If the government decides to monitor the companies’ data collection themselves, do they even have the necessary technology to do so? Also, how does the government measure data in order to tax it? While current technological and legal analyses fail to provide certain answers to these questions, they should not stand in the way of something as important and necessary as a data tax. Once the logistics have been worked out, the tax will be well worth it.

A data tax is a big idea. It would drastically reshape the tech industry. It would alienate some of the wealthiest people in the world and infuriate prominent conservative politicians, but it is necessary. At a time when every state in the US is experiencing a decline in tax revenue and unemployment is coming off record-high levels, the billions of dollars in proceeds from this tax could be put to good use. As more of our lives shift online, the market for data will continue to grow and the algorithms that extract and use our data will become increasingly sophisticated. We need to start thinking of these companies’ mass collection of data as a true existential threat. Considering these stakes, a data tax is not an extreme idea at all.