It is no exaggeration to say that competition has made our world what it is today. States compete over resources, people, and the myriad other factors that raise thrones or topple them. Businesses, driven by the gales of market competition, discard yesterday’s products and refashion them into today’s innovations. Individuals, too, ceaselessly compete amongst themselves for professional, personal, or romantic gain—all in the hopes of building a satisfying life.

In some domains, a lack of competition is the largest hindrance to equitable outcomes. Mitsuki Jiang demonstrates the desperate need for competition in the increasingly ossified pharmaceutical market—and profiles the new players ready to provide just that. In “A New Prescription,” she explains that these alternative pharmacy models, though effective at making generic medications vastly more affordable, fall short when it comes to brand-name prescriptions. The antidote, Jiang argues, is federal intervention designed to level the playing field.

Competition is not always a panacea, however. Israel, a multiethnic, multilingual state, is fracturing under the weight of discriminatory policies. In “Twisted Tongues,” Nina Lidar notes that the increasing marginalization of Arabic is exacerbating competition and inhibiting understanding between Jews and Arabs. To unite the state, per Lidar, the Israeli government must work toward equality by dismantling laws that make Arabic a second-class language.

In a familiar form of geopolitical competition, the fight between the West and Russia for influence in the Balkans is rapidly reaching a breaking point, as Ashton Higgins shows in “The Southern Slavs Asunder.” Though Serbia has long been in the Russian orbit due to the lingering effects of Pan-Slavism, Russia’s growing militarism and the West’s economic attractiveness are

causing Serbians to become leery of their longtime patron. If Serbia turns Westward, Higgins contends, Russia’s quest for Balkan hegemony may be at an end.

As states continue to compete for geopolitical supremacy, they are taking the fight to a new front: the digital realm. Daniel KyteZable’s “A Race to the End of Time” explores Q-Day, the fast-approaching moment when quantum computers render current digital security systems obsolete. With the United States and China competing to improve their quantum chops, the Global South is becoming increasingly vulnerable to digital exploitation. Such technological advancements, Kyte-Zable argues, are likely to increase global inequality.

While futuristic technology has pernicious implications in the battle between nations, it might be just what is needed when competing with nature. In “Man vs. Mosquito,” Aman Vora shines a light on the increasingly frantic conflict between scientists seeking to end the scourge of mosquito-borne illness and the insects’ adaptations that keep the threat alive. Vora argues that the threat of diseases such as dengue and malaria is grave enough to justify using cutting-edge tools like gene editing, even if they cause apprehension for some.

We hope this special feature, rather than providing a one-dimensional perspective on competition, will remind you of its immense power for good or ill. Even as competition inexorably scours away deficiencies in markets or organizations, its all-encompassing tide sweeps away protections trusted by the vulnerable and traditions long-cherished by all. Therefore, we enjoin you not to get so caught up in the fire of competition that you forget the many benefits cooperation can bring.

– Isabel & Bryce

EDITORS IN CHIEF

Isabel Greider

Bryce Vist

CHIEFS OF STAFF

Gus LaFave

Alexander Lee

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICERS

Rohan Leveille

Annabel Williams

MANAGING EDITORS

Grace Chaikin

Harry Flores

Elliot Smith

CHIEF COPY EDITORS

Grace Leclerc

Miguel Valdovinos

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Hiram Valladares Castro-Lopez

Yuliya Velhan

DATA DIRECTORS

Ryan Doherty

Asher Labovich

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Christine Wang

Thomas Dimayuga

Haimeng Ge

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTORS

Matias Gersberg

Mitsuki Jiang

WEB DIRECTOR

Kevin Kim

DIVERSITY OFFICER

Jordan Lac

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Hiram Valladares Castro-Lopez

Yuliya Velhan

DEPUTY INTERVIEWS

DIRECTORS

Alexander Delaney

Ben Ringel

Matteo Papadopoulos

Mira Mehta

INTERVIEWS ASSOCIATES

Alexandra Lehman

Ariella Reynolds

Avital Strauss

Benjamin Greenberg

Benjamin Stern

Charles Adams

Charles Wortman

Colten Edelman

Eiffel Sunga

Elijah Dahunsi

Ellia Sweeney

Emma Brankstein

Emma Stroupe

Gabi Yuan

Henry Robbins

Jie Yu Kuo

Justin Meszler

Kate Javerbaum

Lina Legesse

Matthew Kotcher

Michael Citarella

Michele Togbe

Miles Munkacy

Nash Riebe

Samuel Trachtenberg

Simon Wordofa

Taleen Sample

Theodore Fisher

William Vogel

Zoe Targoff

Alexander Samaha

Alexandros Diplas

Allison Meakem

Hannah Severyns

Isabel Tejera

Tiffany Pai

Zander Blitzer

DATA DIRECTORS

Ryan Doherty

Asher Labovich

DATA ASSOCIATES

Aimee Zhang

Alex Freehoff

Alex Wick

Amanda Sun

Amine Chajar

Amy Qiao

Ariel Shifrin

Benjamin Buka

Casey Crockett

Chai Harsha

Gabi Yuan

Irene Zhao

Jed Morgan

Jennifer Shim

Jester Abella

Jo Gasior-Kavishe

Logan Rabe

Nikhil Das

Sita Pawar

Sofia Barnett

Tiffany Kuo

Titi Zhang

William Yu

CHIEF COPY

EDITORS

Grace Leclerc

Miguel Valdovinos

MANAGING COPY

EDITORS

Renee Kuo

Tiffany Eddy

COPY EDITORS

Anum Azhar

Benjamin Levy

Darisel Velez

Davis Kelly

Desi Silverman-Joseph

Ellie Brault

Emily Colon

Harshil Garg

Maddy Brooks

Nicolas Clampitt

Sara Santacruz

Yael Wellisch

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Matias Gersberg

Mitsuki Jiang

MULTIMEDIA ASSOCIATES

Michele Togbe

Leyad Zavriyev

Jack Stein

Erica Yun

Catharine Paik

BUSINESS DIRECTORS

Rohan Leveille

Annabel Williams

BUSINESS ASSOCIATES

Mariana Melzer

Gabi Yuan

Manav Musunuru

Mehari Milton

John Lee

Caroline Novatney

WEB DIRECTOR

Kevin Kim

WEB DEVELOPERS

Akshay Mehta

Alex Wick

Anh Nguyen

Armaan Patankar

Brooke Wangenheim

Devon Kear-Leng

Hao Wen

Narin Kim

Nicholas Kitahata

Shafiul Haque

William Yu

MANAGING EDITORS

Grace Chaikin

Harry Flores

Elliot Smith

SENIOR EDITORS

Amina Fayaz

Ashton Higgins

Elsa Lehrer

Suzie Zhang

EDITORS

Aman Vora

Ariella Reynolds

Daphne Dluzniewski

Ela Snyder

Jodi Robinson

Kenneth Kalu

Rohan Pankaj

Sofie Zeruto

Sophie Forstner

Steve Robinson

William Loughridge

STAFF WRITERS

Ananya Narayanan

Andreas Rivera Young

Annika Reff

Brianna Paliz

Cecilia Hult

Chiupong Huang

Colten Edelman

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Daria Dmitrieva

Ellie Silverman

Evan Tao

Gigi Alioto-Pier

Jeremy Gold

Jordan Lac

Julianna Muzyczyszyn

Kayla Morrison

Keyes Sumner

McConnell Bristol

Mia Madden

Mitsuki Jiang

Morgan Dethlefsen

Nathan Haronian

Neve Diaz-Carr

Nicolaas Schmid

Nina Lidar

Noah Kim

Ophir Berrin

Phil Avilov

Ross Rutherford

Sonya Rashkovan

Tianran (Alice) Cheng

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Christine Wang

Thomas Dimayuga

Haimeng Ge

DESIGN DIRECTORS

Muhaddisa Ali

Patrick Farrell

Hannah Jeong

GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Natalie Ho

Hyunmin Kim

Claire Lin

Elliott Romano

ART DIRECTORS

Lana Wang

Jason Aragon

Jacob Gong

Lucia Li

Maria Hahne

Ziwei Chen

Grace Liu

Angela Xu

COVER ARTIST

Su Yun Song

ILLUSTRATORS

Alexandra Zeigler

Ariel Pan

Ashley Nguyen

Ayca Tuzer

Carmina Lopez

Eliza Goodwin

Emmie Wu

Haley Sheridan

Hannah Rice

Hye Won (Hayley) Kim

Kaitlyn Stanton

Kex Huang

Kyla Dang

Larisa Kachko

Lily Engblom-Stryker

Peishan Yu

Qingyang (Tiffany) Zhu

Rafael Mediodia

Samantha Takeda

Sarah Mason

Sophia Spagna

Xinyi Liu

Xinyuan (Fiona) Song

Yan (Jessica) Jiang

Yuan Jiang

Yushan (Sabrina) Jiang

DIVERSITY OFFICER

Jordan Lac

DIVERSITY ASSOCIATES

Alexander Delaney

Ilektra Bampicha-Ninou

Titi Zhang

Federal and state governments are abdicating their duty to provide the Navajo Nation with water

by Nicolaas Schmid ’27, an International and Public Affairs concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR

illustration by Hye Won (Hayley) Kim ’24, an Illustration major at

RISD and illustrator for BPR

As the American Southwest struggles through a regional “megadrought”—the worst of its kind in 1,200 years—states continue to battle for nature’s most abundant, yet most precious, resource. Southwestern state governments are particularly concerned about who should get Colorado River water, with each state striving to funnel a portion of the limited supply to itself. These enduring negotiations over water allocation, however, have largely ignored a critical population in the region: the Navajo.

Covering an area larger than West Virginia, the Navajo Reservation is home to over 170,000 people, close to a third of whom lack access to reliable running water. Although present conditions are astonishingly dismal, this crisis has been decades in the making—and the federal and Arizona governments have been anything but helpful in solving it. Ever since the Navajo were forcefully removed from their ancestral homelands and subsequently returned to a fraction of their territory, they have struggled to survive in the face of US complacency. To address the resource crisis on the Reservation and rectify historical wrongs, states should look beyond their own needs and collaborate with the federal government to deliver water to the Navajo Nation.

The scarcity of water on the Reservation impacts nearly every aspect of daily life. Even before the drought, families on the Reservation reported having to drive miles to reach water stations where they could fill up their storage tanks. For those without outhouses, the lack of running water means getting in the car and driving to the nearest toilet each time they need to use the restroom. Even Buu Nygren, the Navajo President, described resorting to using “windmill water that is supposed to be for livestock.” State governments stood by as the lack of water made adequate hand-washing impossible during the Covid-19 pandemic. Cases and deaths on the Reservation skyrocketed—the Navajo infection rate was higher than that of New York, and their

Covid-19 mortality rate surpassed that of any state in the country.

Moreover, the water that the Navajo can access is often tainted by irresponsible government projects: Some of the Navajo Nation’s already scarce groundwater sources have been rendered unusable by uranium mining projects that contaminate surrounding areas with radioactive particles. Stricken by both drought and a lack of viable water sources to begin with, access to clean water remains a priority for the Nation. Like most governments in the Southwest, the Navajo are looking to the Colorado River to resolve their current crisis.

The question of whether Indigenous tribes have the right to water from the Colorado has already been settled—116 years ago, to be exact. In its 1908 Winters v. United States decision, the Supreme Court affirmed that the United States must guarantee Native populations the water

required for their operations to fulfill its side of the 19th-century treaties that created the reservations. Although this was a landmark affirmation of Indigenous rights across the country, the case did not explicitly determine how the tribes would secure their allotted resources.

It was not long before Southwestern states began rolling back the advancements made by Winters. In 1922, states in the Colorado River Basin ratified a compact to settle river disputes in the region. A provision in the agreement denied that the United States held any obligation to assert or protect the water rights of tribal governments. Instead, one by one, each tribe in the region has been forced to make separate compacts with the states in which they are located.

Over 80 years later, federal inaction sanctioned by state governments has left the Navajo Nation negotiating alone with the state of Arizona to obtain the water resources it needs. Arizona has hurled numerous obstacles at Navajo attempts to secure a fair water allotment: Decades-long court cases and drawn-out hydrological assessments have nullified any progress made during negotiations. In a show of state superiority, Arizona has even tried— albeit unsuccessfully—to leverage the tribe’s casino license to force a favorable settlement for Arizona citizens. The fight is rigged, and the power dynamic between Arizona and the Navajo Nation has made it difficult to reach an agreement that comes out fair for both parties.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, a century after Winters was decided, the Navajo returned to the Supreme Court to demand their rightful access to water via federal authority in 2023. In its Arizona v. Navajo Nation decision, the Court denied the tribe’s request to get the federal government involved, claiming the treaty that created the Reservation did not mandate the federal government to actively protect the tribe’s water access, despite the federal government maintaining authority in state-tribal relations. The majority opinion further argued that “Indian treaties cannot be rewritten or expanded beyond their clear terms.” What good is a treaty

that provides dry land to a tribe if the water necessary for survival does not accompany it? Justice Neil Gorsuch, siding with the Navajo in a striking dissent, described their situation best, writing that the Navajo have been “told repeatedly that they have been standing in the wrong line and must try another.”

Despite another blow from the federal government, all hope for an agreement with Arizona is not lost. In February, the Navajo Nation released a summary of a current proposal in the works with the state, expressing confidence that a settlement will be reached soon. The proposal will affirm Navajo claims to water in the Colorado River Basin. Yet even with an agreement seemingly on the horizon, there is little confidence that this century-long impasse will be overcome. The Navajo need water now, but some court hearings for resource adjudication are not even scheduled to begin until 2027.

Furthermore, even if an agreement is struck with Arizona, congressional funding for key water infrastructure projects—vital for ensuring that the allocated water actually gets to the Reservation—is not guaranteed. In 2010, talks between the Navajo and Colorado River authorities resulted in a consensus, but the agreement was shut down by Congress. The federal government thought that the burden of the $800 million infrastructure projects included in the compromise outweighed the dire situation on the Reservation.

Just last year, testifying in front of the Senate, President Nygren asked the body to fund key infrastructure projects that would bring water to the Nation from the San Juan River. Nygren said that the Navajo had been too occupied “worrying about basic essentials of life” to focus on “moving forward” and “building [themselves] up.” It is time that the federal government upholds its duty to “secure the permanent prosperity and happiness” of the Navajo people, as stated in its 1849 treaty with the tribe. The Navajo need enough water to drink, bathe, and nourish their fields—only then can they meaningfully grow as a nation.

“What good is a treaty that provides dry land to a tribe if the water necessary for survival does not accompany it?”

fine total increased every day the strike went on. In response to the strike, Massachusetts lawmakers have proposed legislation to allow public sector employees, except those working in public safety, to strike after six months of negotiations have passed. This legislation has stalled.

Public sector strikes in the United States were common in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1968, for instance, sanitation workers went on strike in New York, leading to pileups of garbage around the city. In 1975, as many as 55,000 state, county, and municipal employees struck for higher wages. These norms changed in 1981, when President Ronald Reagan fired over 11,000 striking air traffic controllers, a disciplinary action virtually unheard of in years prior. His decision created nationwide hostility toward public sector strikes—hostility that has continued into the present.

Public sector employees must have the same right to strike as their private sector counterparts

by Evan Tao ’27, an International and Public Affairs concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR

On January 19, 2024, teachers went on strike in the Boston suburb of Newton, Massachusetts. Before their union came to the decision to strike—with 98 percent of members voting in favor—it spent 10 months negotiating new contracts with the city to no avail. By striking, the teachers hoped to secure pay increases on par with hikes in Newton’s cost of living, especially for classroom aides. They also demanded social workers in every school, describing them as essential to students’ mental well-being, particularly after the pandemic. Furthermore, in fiscal year 2024, the school district’s budget was cut by nearly $4 million, even as the city posted nearly $29 million in surplus.

By February 2, the strike ended, with teachers having successfully secured many of their goals. Troublingly, however, the city’s children had missed 11 days of school, and their parents had been forced to scramble to adjust their schedules. Anger over the economic harm of such a lengthy strike has sparked debates in

the community on whether teachers, and public sector employees as a whole, should strike at all. While there are strong arguments against public sector strikes, organizing to withhold labor remains one of the few means employees have to reclaim power and advocate for their needs. The right of teachers to strike must be safeguarded. The strike divided Newton families over who bore the brunt of the blame. Parents groups released an open letter blaming Mayor Ruthanne Fuller’s budget cuts for the strike. In it, they explained, “We worry that [Mayor Fuller] is out of touch with the reality of our public schools. Our trust in her has eroded every time she’s chosen not to prioritize our children.” Others, conversely, blamed the teachers’ union for delaying negotiations. A group of parents filed a class-action lawsuit against the union, claiming that it “chose its illegal strike and chose to bear the costs of contempt of court to keep striking to drive parents to a point of desperation: ‘Pay them whatever they want, just get my kid back in school.’ That was willful, wanton, and wrong.”

Teachers’ strikes are technically illegal in Massachusetts, but teachers in the state often withhold labor anyway in contempt of court. For breaking the law, the Newton union will pay $625,000 in fines to both the city and state—the

There are many legitimate arguments used to justify this enmity. Public sector workers provide essential services, from education to air traffic control to emergency response. Unlike in the private sector, customers cannot switch services easily: A parent cannot move their child to another school as simply as they can start shopping at another grocery store. When teachers strike, students and families suffer. Further, public sector employees have access to unique channels for negotiation, like lobbying for government policies to increase their pay. Other arguments contend that public sector employees have a civic duty to provide services and that this duty should be prioritized over their private interests. From that perspective, striking represents a breach of public trust.

Engaging with these arguments more deeply, however, reveals their fragility. Although a teacher strike hurts the public in the short term, long-term school underfunding hurts it more. Which is worse for a student: missing school for 11 days or attending a decrepit school with underpaid teachers for 12 years? Teacher strikes ultimately serve, not hurt, the public interest. Additionally, in employer-employee relationships, the employer typically holds the majority of power. Striking remains the most powerful tool unions have to secure victories for their workers, including teachers.

Admittedly, striking can be dangerous in certain portions of the public sector, such as police and fire departments. These workers should arguably never strike and instead use other avenues for self-advocacy. To pull another example from Massachusetts history, in 1919 Boston police officers went on strike, and riots and robberies quickly followed. (Like the air traffic controller strike 62 years later, this strike was busted by a famously pro-business Republican: then-governor Calvin Coolidge.) However, there is a bright line between safety and non-safety

workers—teachers and sanitation workers are not the same as police officers and firefighters.

In Newton, striking was certainly the union’s last resort; alternate avenues for negotiation had failed teachers repeatedly. Contract negotiations had taken place behind the scenes for almost a year beforehand, and policies that would have raised school budgets by increasing property taxes had been rejected by voters. Contrary to the idea that teachers had incentives to “hold children’s education hostage” to stall negotiations, the union faced increased fines every day the strike went on. If anything, it was in the school committee’s interest to stall.

So why do so many observers default to blaming the teachers, and not the school committee, for drawing out negotiations? Precedents like Reagan’s strike crackdown have normalized anti-union sentiments, making it easy to paint unions as greedy and indifferent to the public good. These misrepresentations fail to consider the fact that teachers serve the public and therefore care what the public thinks of them. When parents are convinced that teachers don’t have students’ best interests in mind, it impacts their ability to do their jobs well.

Most of all, the illegality of teacher strikes allows opponents to claim the moral high ground. One observer in the Boston Globe

“Which is worse for a student: missing school for 11 days or attending a decrepit school with underpaid teachers for 12 years? Teacher strikes ultimately serve, not hurt, the public interest.”

argued, “Newton educators are teaching their students that breaking the law and thumbing one’s nose at a judge’s order are OK—if it is in your self-interest.” Never mind that a primary strike demand was to secure mental health support for students and that the union was willing to incur hefty fines to that end. On the contrary, Newton educators are teaching their students the importance of standing up for themselves and others.

What would it look like if employers faced the heat? Let’s flip the argument about civic duty: Even more than their employees, public sector employers like school committees bear the primary responsibility for providing public services. Employers should, by default, be held accountable for failing to successfully negotiate with their employees, as this failure impedes their duty to deliver services to the public.

To shift the burden onto employers, Newton voters must hold their city officials accountable at the voting booth. They can also support teachers by legalizing the right to strike. Ultimately, witnessing the teacher strike will provide students with a better civics lesson than any day in the classroom could.

Interview by Name ‘XX

Illustration by Name ‘XX

Interviewee Description.

Elfidar Iltebir is the president of the Uyghur American Association, an organization dedicated to preserving Uyghur culture, serving the Uyghur diaspora, and engaging in activism to protect Uyghur human rights. Born in Ürümqi, Xinjiang (also known as East Turkestan), China, she grew up in Türkiye and has lived in the United States since 2000. Iltebir has led campaigns to raise awareness in the United States about crimes against the Uyghur people and to mobilize support for legislation opposing such crimes. She also provides translation services to community members. Outside of her activism, she is currently a structure analyst at an energy firm.

This is a question. Do not indent questions. This is a response. Do not indent responses unless it is the start of a new paragraph within the same response. There should be no extra line space between a question and a response. Line space should only be present between the end of a response and the beginning of a new question.

Mira Mehta: A lot of people don’t know or have denied the accusations that the Chinese government is committing genocide against the Uyghur people. What do you see as the biggest barrier to informing people about the situation?

Elfidar Iltebir: First of all, there is forced sterilization. The birth rate fell by 60 percent from 2015 to 2019. That is a way of proving that Uyghurs are being basically killed before they’re even born. Another part is children being separated from their families. When the parents are in concentration camps, forced labor factories, and prisons—sent or taken to those places— children are taken to state-run orphanages, boarding schools, and kindergartens. From age four to grade 12, kids are being separated from their families. Phase two is indoctrination: They have stripped away their language, their culture, their religion, their familial bonds—their world, basically. So that is another part that fits into genocide.

Another argument we Uyghurs make is that China has already studied the Genocide Convention, and they’re doing it with different tools than what we know as genocide. In the past, for example, in the Holocaust, there were mass killings in gas chambers. The Chinese government is not doing that, but they have DNA and full biometric data of all the Uyghurs in the camps, and they’re using us as a ready market for an organ harvesting business. Besides that, if you remember two years ago, Customs and Border Protection officials in New York confiscated 13 tons of hair. That’s hundreds of thousands of prisoners’ and detainees’ hair. And so they’re not

just keeping us away from our families and using us for forced labor, they’re also selling us piece by piece with our hair and our organs, using us as a testing zone for their medicines, for their technology, facial and voice recognition tools, and so many other things.

So this is definitely a genocide, but because of China’s strong control of its own internet, we are not providing enough videos and documents—like what’s going on in Israel, or Gaza, or Ukraine, or when there is an earthquake— for people to believe what is happening. When something happens somewhere else in the world, people share it. We still see leaked documents, leaked videos here and there on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok). But of course, there is very strong control. What we are hearing and seeing is the tip of the iceberg, basically. The Chinese government is also sending journalists away and not giving them access to forced labor camps. China is hiding them, and they’re very good at this—committing genocide behind closed doors and still enjoying impunity at the United Nations and elsewhere.

MM: You’ve talked about looking for solidarity and looking for people to take more action. What role do you think the United States can or should play in supporting Uyghur people?

EI: The United States has been playing a lot of roles so far, so I want to start with appreciation and gratitude. Some of that action is also linked to our hard work because some countries try to look at this issue as Western or US propaganda or exaggeration. It hurts me so much because we—as in Uyghurs—were asking for time off

from work for weeks and weeks and knocking on every single door on Capitol Hill, explaining what’s going on to every single Congress member. We wrote thousands of letters. We tried our best to raise awareness in the United States, and then US lawmakers began to understand what’s happening. Citizens of other countries don’t have access to their Congresses as we do in the United States. Here, we are, thank God, allowed to talk to our own Congress members and say, “I’m a US citizen, and this is happening to my family. This is happening to my hometown.” So in that way, we are lucky in the United States. And, back to your question, how can people in the United States help? They can still call their Congress members and senators to pass Uyghurrelated bills. So right now, there is one bill called the Uyghur Policy Act that helps protect Uyghur activists. It also has provisions for the United States to help the Uyghur cause. For example, it would increase Uyghur-cause-related work at the United Nations, increase coordination with other countries, and have the State Department appoint a special coordinator to handle Uyghur issues. That’s not the only bill, of course. There is also the Transnational Repression Policy Act, which protects Uyghurs on US soil, and a Uyghur organ harvesting bill. So, supporting things like that is one way the United States can help.

Edited for length and clarity.

Edited for length and clarity.

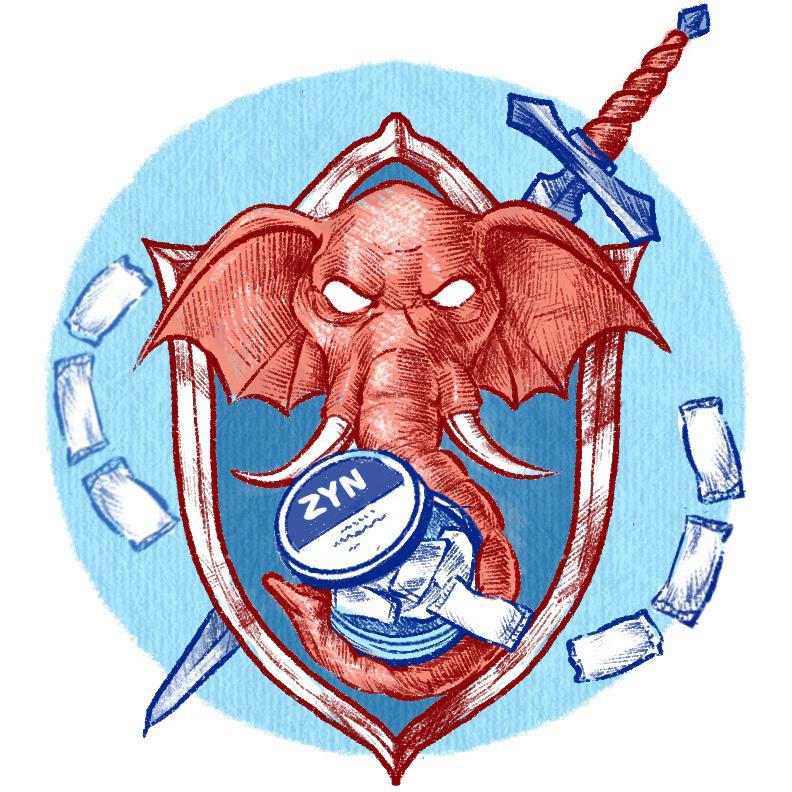

Democrats’ attacks on Zyns threaten to give the GOP an opportunity to target young voters

by Andreas Rivera Young ‘24, a History and Political Science concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR illustration by Sarah Mason ‘26, an Illustration major at RISD and illustrator for BPR

Zynbabwe. Lip Pillow. Zynnachino. Upper Decky.

These are just a few of the nicknames given to Zyns, flavored nicotine pouches that users place between their lips and gums. Zyns have flooded college campuses and achieved popularity similar to that of vaping in the 2010s, thanks to their prominence on TikTok, brand endorsements from professional sports leagues like Major League Baseball, and promotion by conservative celebrities like Tucker Carlson and Joe Rogan. They now comprise 24 percent of the smokeless nicotine market despite being a relatively new product. Since Zyns do not contain tobacco, they present a lesser risk of gum cancer and other health risks typically associated with staples like chewing tobacco, making the product more attractive to many users.

The rising popularity of Zyns has attracted regulatory scrutiny. In January, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) urged the Federal Trade Commission and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to regulate Zyns. He specifically cited the marketing practices of Philip Morris International—the company that sells Zyns—which he claimed target adolescents. While his mission is valiant, Schumer will need to build a larger coalition to battle against Republican lawmakers who have already weaponized his FDA referral. Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC), for instance, posted an image of himself with a tin of Zyns on X, captioning the post, “Come and take it, Chuck.” Tillis, like many other Republican leaders, is framing Democrats’ attempts to regulate Zyns as part of a broader attack on the freedoms of Americans.

The Republican strategy is potentially very

effective. Democrats appear Big Brother-esque, telling individuals what they can and cannot consume and exerting undue influence on the private sphere. Using this strategy, Republicans can target young voters, with whom they face a 21-point deficit in recent polls. Democrats also have to contend with intense lobbying efforts conducted by Philip Morris. The company, which has historically spent millions of dollars every year to pressure policymakers to loosen restrictions on the nicotine industry, purchased Swedish Match—the original fabricator and owner of the Zyn brand—for $16 billion in 2022. As Zyns have soared in popularity, Philip Morris has hired more lobbyists to pressure US lawmakers to ensure that federal regulators leave their new product alone. These lobbying efforts may explain some Republicans’ reluctance to regulate Zyns.

How can Democrats fight back? Most obviously, the party could try to focus attention on the health impacts of Zyns on young users rather than allow itself to be drawn into Republicans’ culture war framing. There is indeed inadequate research on the health outcomes of Zyn users, an issue that the FDA could easily resolve by funding more research on the topic. Nicotine has previously been shown to be particularly harmful for adolescents, who are at greater risk of forming an addiction due to their brain chemistry. Democrats should focus on researching Zyns’ health consequences instead of regulating and taxing the product for all users.

But Republicans may be able to portray even this limited regulation strategy as government overreach, as any potential broadside

against Zyns could be refashioned into a rallying cry against nicotine regulation as a whole. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) has even had time to call for a “Zynsurrection,” referencing the January 6 insurrection. Messaging like Greene’s shows how drastically Republicans are spinning this issue to subsume it into the culture war. A potential avenue for Democrats to defuse this line of attack would be to engage groups such as Parents Against Vaping E-cigarettes to fight the blowback. By attracting parent groups, Democrats could position themselves as explicitly looking out for child safety rather than policing adult nicotine use.

Regulators will likely crack down on Zyns if dangerous health effects are discovered, just as they did with vaping a few years ago. Until then, however, Democrats should leave Zyns alone rather than rushing to regulate and tax them. Action more aggressive than the FDA referral will only give Republicans additional ammunition in the culture war. Many people addicted to nicotine will continue to use the substance no matter what the government does to stop them, so policymakers should focus on harm reduction rather than ending nicotine use outright. Democrats should center their messaging more explicitly on child safety and increased research funding while building a coalition of Zyn-skeptics in the long term. There are various ways to go about keeping Zyns out of adolescents’ hands, but rushing to regulate this product is a recipe for political disaster right before the 2024 elections.

How the GOP has been forced to choose popular opinion over pro-life allies

by Jesse Eick

’26.5, an International and Public Affairs and History concentrator

illustrations by Ruobing Chang ’25, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

On February 16, 2024, in a scripture-filled concurrence for LePage v. The Center for Reproductive Medicine, Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Tom Parker asserted three ideals that form the “theologically based view of the sanctity of life adopted by the people of Alabama”: “(1) God made every person in His image; (2) each person therefore has a value that far exceeds the ability of human beings to calculate; and (3) human life cannot be wrongfully destroyed without incurring the wrath of a holy God, who views the destruction of His image as an affront to Himself.”

In the case, an 8-1 majority decided that “the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act applies to all unborn children, regardless of their location.” While one might expect abortion opponents to applaud this decision, LePage has created fierce competition between two flanks of the Christian right: those who want to protect “life” in its every form and those who support creating life through methods such as in vitro fertilization (IVF). In a post-Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health

Organization world, Republican leaders are stuck in a quagmire, forced to abandon their longtime anti-abortion allies on the issue of IVF for the sake of broader public opinion.

LePage was filed by three couples who underwent IVF treatment at a Mobile, Alabama fertility clinic. After each of the couples had given birth to healthy babies, they paid to cryo-preserve the additional embryos created during the IVF process for potential use in later pregnancies. However, the frozen embryos were accidentally destroyed after a patient opened one of the freezers in which they were stored. The plaintiffs posited that the destruction of these embryos constituted a wrongful death, violating the 1872 Wrongful Death of a Minor Act. The Alabama Supreme Court agreed, transforming extrauterine embryos from property into persons entitled to rights.

In the week after the LePage decision was released, three IVF providers in the state— including the defendant in the case, The Center for Reproductive Medicine at Mobile Infirmary— halted their services for fear of legal repercussions. The IVF process often creates excess embryos, some of which might ultimately be disposed of due to inviability, genetic abnormality, or patients’ decisions not to use them. However, after the Court’s decision, any embryos

discarded in the state of Alabama will be legally considered murdered children. Employees at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, one of the clinics that paused its services, announced that they were “saddened that this will impact our patients’ attempt to have a baby through IVF, but we must evaluate the potential that our patients and our physicians could be prosecuted criminally or face punitive damages for following the standard of care for IVF treatments.”

While this decision caused consternation in the medical world, it also sparked debates in Republican circles. Since the largely unpopular Dobbs decision, Republican leaders have struggled not to be cast as extremists in the abortion debate. IVF is a hugely popular procedure supported by 86 percent of Americans and 58 percent of Republican voters—supporting it enables Republican lawmakers to appear on the side of popular, common-sense policy. Moreover, in a world in which 42 percent of Americans say they or someone they know has used fertility treatments, IVF is an essential means of procreation. The GOP has historically been a family-values party and thus wishes to support modern medicine that can aid family expansion.

Consequently, in the weeks following the decision, congressional Republicans jumped to clarify their support for IVF procedures and those who pursue them. Senate GOP campaign materials advised candidates to “clearly state support for IVF” and “publicly oppose any efforts to restrict access” to it. Senator Roger Marshall (R-KS) expounded that “there’s nothing more pro-family than supporting the birth of babies…I am absolutely certain that in vitro fertilization is a great thing, that God has given us this technology and we should use it.” In the Republican response to President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address, Senator Katie Britt (R-AL) said, “[W]e strongly support continued

“By attempting to stand on the side of IVF and public opinion, GOP leaders are threatening to shatter their union with the anti-abortion lobby—a union that has existed since the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973.”

nearing the end of his life, has incalculable value that deserves and is guaranteed legal protection.”

Rose’s tone quickly soured after Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed the bill shielding IVF providers from liability: She lamented, “Tragically, the Governor of Alabama has given the IVF industry a license to kill.” She further stated, “Politicians cannot call themselves prolife, affirm the truth that human life begins at the moment of fertilization and then enact laws that allow the callous killing of these preborn children simply because they were created through IVF.” Pro-life groups are even running ads against Republican representatives who vote to protect IVF, employing the disturbing images of scalpels, gore, and infants commonly found in anti-abortion campaigns. While this imagery is typically levied against pro-choice Democrats, anti-abortion groups are now attacking the prolife Republicans who were once their allies.

nationwide access to in vitro fertilization. We want to help loving moms and dads bring precious life into this world.” Three weeks later, the Alabama state legislature affirmed its support for the treatment, passing a bill to protect IVF providers from legal liability and rendering moot the anti-IVF implications of the LePage ruling.

However, while members of the Republican Party were vocalizing their support for IVF, anti-abortion political action groups across the country were celebrating the LePage decision. Following the ruling, Lila Rose, president and founder of the pro-life group Live Action, applauded the Court for recognizing that “[e] ach person, from the tiniest embryo to an elder

The fact that anti-abortion groups are targeting politicians they would typically support emphasizes the tension caused by the IVF issue. By attempting to stand on the side of IVF and public opinion, GOP leaders are threatening to shatter their union with the anti-abortion lobby—a union that has existed since the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973. Perhaps this is a politically savvy move: Although the anti-abortion Christian right have been staunch supporters of the GOP establishment, their extreme views are by no means popular among the broader electorate. On the other hand, might losing such a loyal voting bloc hurt the Republican political cause? The full impacts of this fissure remain to be seen in November.

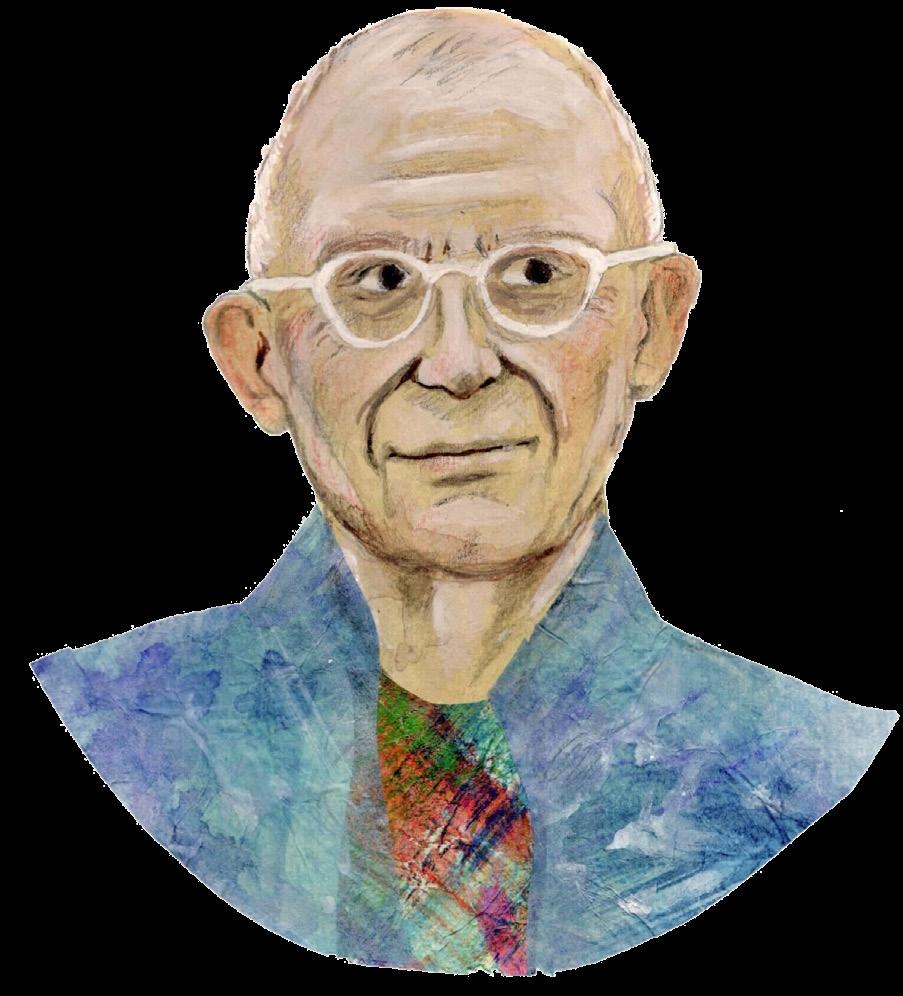

A world-renowned moral and political philosopher, T.M. Scanlon spent over 35 years at Harvard (and before that, at Princeton) as a scholar, teacher, and writer dedicated to addressing questions about morality, justice, and rights. One of his books, What We Owe to Each Other, became the basis of moral contractualism, a theory proposing that morality originates from agreements between people. It shapes contemporary thinking on everything from public health to economic equality to the fundamental social and political contracts that sustain our democracy. It also framed a four-season hit show on NBC called The Good Place, in which characters actively deploy the philosophy to redesign the afterlife.

Ariella Reynolds: In 1998, you published your seminal treatise on contractualism, What We Owe to Each Other, in which you say the judgments of right and wrong are “judgments about what would be permitted by principles that could not reasonably be rejected, by people who were moved to find principles for the general regulation of behavior that others, similarly motivated, could not reasonably reject.” What do I owe you? Do I owe you something different from what I owe my family?

T.M. Scanlon: This philosophy is about what we can justify to people in general. When I first wrote an article called “Contractualism and Utilitarianism,” which came out in 1982, I said that I was going to give an account of morality.

But by 1998, I’d narrowed my focus. Contractualism wasn’t everything you called morality. That is, you could try to justify, on the basis of contractualist principles, the duty to take care of your children. And I thought, there are other things that are clearly part of the morality of right or wrong in a general sense, and I wasn’t giving an account of all of that. Morality, as people commonly use it, doesn’t refer to a single subject. So I just redefined the subject as what we owed to each other. That was why I called the book What We Owe to Each Other

AR: You’ve said in other interviews that Michael Schur, the creator of The Good Place, discovered you—and contractualism—by way of one of your graduate students who was working on a paper about whether it was possible for human beings to improve. Do you think we are improving as human beings?

TMS: Mike Schur did a terrific job. It’s a wonderful show. And I was, of course, flattered that he liked my book. But he describes the kind of justification involved in contractualism as something like a real-time attempt to actually convince people, whereas I want to say an act is wrong if people would have good reason to reject any principle that permitted it—which isn’t a matter of whether they would agree to it in fact or not.

I’m inclined to think that an awful lot of people, maybe even most people, care about being good human beings by some standard of goodness, although they have very different standards of goodness in mind. I mean, part of the appeal of many religious doctrines is that they provide a model in which people can feel that they’re good people. But that’s just a hypothesis. And that doesn’t necessarily draw people together because they have different ideas about what makes people good.

AR: Three university presidents were unable to condemn open calls on campus for genocide against Jews. In your view, what does moral clarity require here? Did these presidents own their responsibility to it?

TMS: The presidents were actually trying to answer the question, and I thought they gave the right answer. I thought that what they said was, “It’s contrary to the idea of a university that university discipline should be brought down on people just because something they say is very seriously morally wrong.” People have to be able to debate about what’s morally right and morally wrong. But the basis of university discipline has to be immediate harm to other people. If I’m threatening you or saying things that genuinely cause you to feel your life’s in danger, then that’s a different matter. But the mere hatefulness of a person’s position isn’t, by itself, grounds for university discipline. I actually think that that’s the correct position, and they basically said that.

AR: The Founding Fathers relied on Enlightenment philosophers, but it doesn’t seem like our government still does. I interviewed Tom Nichols, a writer for The Atlantic, who said that our democracy is hanging by a thread. So you’d think now would be the time to bring back the philosophers. Why don’t they have a seat at the table?

“I’m inclined to think that an awful lot of people, maybe even most people, care about being good human beings by some standard of goodness, although they have very different standards of goodness in mind.”

TMS: It’s understandable that people are not just doing philosophy. And this is a point that Socrates makes in that dialogue: Often, people think of philosophical argument as being successful if it can be used to persuade other people, and that’s what we hope for. But I think a lot of people think they’ve already got their minds made up. They aren’t feeling any uncertainty about that, and they’re just trying to persuade other people or prevent other people from persuading third parties or something like that.

AR: You were part of a discussion group of 10 to 12 people back in your Princeton days with luminaries such as Tom Nagel, Ronald Dworkin, Robert Nozick, and many others. In an interview with The Utopian, you called this the most important time in your philosophical development. What made it so important?

TMS: Well, it was like having this gang of great teachers, for one thing. In my career, I was mainly doing logic, philosophy, mathematics, and things like that, although I was interested in moral and political philosophy, and I got more drawn into it because I was doing a lot of teaching in that area. So this was partly a way of developing more expertise in the field. Second, it was something that provided me with confidence that other people think that we’re not just banging things up, that there’s something there. And that gave me confidence in myself, because these people were willing to talk to me, and so I could be a member of this group, which was amazingly flattering. I was kind of a junior partner in the group, so I thought, “Wow, this is amazing.”

AR: What sorts of things are you working on now? I know you mentioned a set of articles. Anything else?

TMS: Well, I guess in the last couple of years or so, one of the main things I’ve been doing is trying to figure out what seems to be really defensible about contractualism. How does it need to be refined in order to be defensible, and what’s really mistaken or maybe confused about it? That’s not much fun. But on the other hand, you feel that you owe it to other people to do it. If you put these misleading ideas out there and somebody even made a television program out of them, then you have to do some damage control, right?

Edited for length and clarity.

Universities must step up to protect their students from transnational oppression

When “Zooey,” a Chinese international student at the Berklee College of Music, put up posters on campus reading, “WE WANT FREEDOM—WE WANT FOOD ON OUR TABLES… STAND WITH CHINESE PEOPLE,” a fellow student and Chinese national, Xiaolei Wu, threatened to send police after Zooey’s family in China and to “chop [her] bastard hands off.” Wu tipped off the Chinese Public Security Agency, doxxed Zooey online, and bombarded her with physical threats on social media. Zooey sought help from her university, which prohibits stalking and harassment. However, Berklee turned her away and did not take action to protect her. It was not until the FBI arrested Wu and a federal court convicted him that the incident was resolved.

equitable access to political and civic life for all students.

Transnational repression is a daily reality for international students on American campuses— one that colleges and universities have been woefully complicit in. The refusal of administrators and faculty at American universities to acknowledge, much less resist, transnational repression means that universities play a key role in making such coercion effective. Its victims are left feeling abandoned and confused, with no trusted allies.

by Chiupong Huang ’27, an English concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR

illustrations by Lucia Li ’24, an Industrial Design major at RISD and Art Director for BPR

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) and other authoritarian nations often attempt to quell dissent and political organizing beyond their borders by using a wide and evolving range of intimidation tactics. These techniques have involved police threatening loved ones in China both physically and financially, counter-organizing with the help of Party-funded Chinese Students and Scholars Associations (CSSAs), online and offline verbal harassment, and surveillance and hacking. Such actions are part and parcel of what has come to be called “transnational repression,” an under-reported and under-addressed phenomenon in American colleges and universities. Universities must combat the use of violence and coercion that impede students’ First Amendment rights to ensure

Echoing experts and organizations that aid victims, I urge universities to create clear guidelines on reporting, prevention, justice, and security—all measures that lie well within universities’ purview. Creating a designated reporting mechanism that connects victims with a network of resources—such as government agencies and campus police—while allowing for potential prosecution is paramount to organizing any response to transnational repression. Furthermore, education for incoming staff and students regarding the rights they are entitled to is needed not only to warn potential perpetrators of consequences but also to illustrate avenues for otherwise disenfranchised students to enjoy their rights. Universities have already successfully employed similar structural protections to combat threats like drug and alcohol misuse and sexual violence. The threat of transnational repression deserves similar attention.

Administrators have refused to protect academic freedom against transnational repression

“University administrators assume that East Asian students are bookish, STEM-oriented, and docile and that their right to freedom of speech does not need to be protected because they do not use it.”

in countless instances like the one at Berklee. In 2023, Zhang Jinrui, a Georgetown Law School student and key organizer of pro-democracy activism at Georgetown, was harassed by a fellow student who was a member of the university’s CSSA branch. The harasser berated and pointed his phone camera at Zhang, telling his friends that he was video-calling Chinese authorities to report Zhang for his pro-democracy activism. Georgetown does not have a specified reporting mechanism for seeking aid or justice in such cases and has allowed its CSSA to continue operating on campus without condemnation. In 2020, members of the Brandeis University CSSA petitioned administrators to cancel a Zoom panel on

the Uyghur genocide. After the date, time, and link to the meeting were published on WeChat, the panel was Zoom-bombed by students who, using the platform’s shared screen draw feature, scrawled “BULLSHIT” over the presenter’s screen and played the Chinese national anthem. Brandeis administrators failed to condemn the act and did not attempt to hold the responsible students accountable. In 2022, a Columbia University student was punched unconscious at a pro-democracy protest. Still, the University refused to issue a public safety alert, signaling indifference toward such violence.

Victims of transnational oppression report that their conversations in seminars might be disclosed to the Chinese embassy and hesitate to enroll in courses on topics the PRC deems “sensitive.” Chuangchuang Chen told ProPublica, “If there are more than three or four Chinese students in the same class, you are scared to talk. A Chinese student is definitely seen in good favor by the Chinese government for reporting someone.” A Georgetown faculty member echoed this sentiment to Radio Free Asia , observing that Chinese students are unable to speak freely in classrooms out of fear that they will be reported by their classmates.

Why would American colleges and universities willfully ignore and tolerate transnational repression despite the obvious harm it creates on their campuses? For one, Chinese students bring in an estimated $12 billion in tuition each year. Without public pressure, universities are reluctant to take any action that would threaten their golden goose. Zhou Fengsuo, the president of Humanitarian China, remarked in an interview for Brown Political Review that universities are complicit in Chinese transnational repression: “They have become part of the problem by basically institutionalizing this fear. They do not want the Chinese student population to feel different from China. That means you are spreading the brainwashing, the fear, here.”

Some PRC-affiliated students and groups also weaponize the language of racial equity and social justice, exploiting the issue of antiAsian hate to pressure universities to ignore transnational repression. The Washington State University CSSA, for instance, hounded the University into removing posters protesting the treatment of ethnic minorities in China by claiming that the posters were racist toward Chinese people. The letter that the Brandeis CSSA sent to administrators urging them to cancel the Uyghur genocide panel also invoked the supposed anti-Asian racism of its target. While these CSSAs co-opt real concerns about racism to advance their agendas, universities’ refusal to defend their Chinese students from transnational repression reflects actual anti-Asian prejudice. This complicity communicates to these students that their safety, academic freedom, and quality of education are a second-class priority. Discussing transnational repression in his classroom, Professor James Millward of Georgetown University told ProPublica that “most Chinese students just want to get educated and get on with their business.” Millward’s statement reflects the attitudes of universities toward their Chinese students more broadly: University administrators assume that East Asian students are bookish, STEM-oriented, and docile and that their right to freedom of speech does not need to be protected because they do not use it.

University officials seem to forget that the purpose of repression is silence, and the invisibility of transnational repression speaks to its danger. While universities have little control over the policies of foreign governments, administrators cannot simply stand by and watch while the powers of an entire state are pitted against individual students. Students at risk of being targeted by foreign governments deserve to know that their universities will denounce their victimization and pursue their safety.

Benjamin Greenberg: Looking back to your career in the public sector at the White House, can you talk about your role as a deputy US trade representative?

Karan Bhatia: The role of the deputy USTR is to support the US trade representative, but also to be the focal point for the president’s trade policy, typically with some particular area of the world. There’s a geographic component to it as well as a substantive component. When I was there, my focal areas were Asia and Africa. This was back in the 2005 to 2007 period, which was a very active time in US international trade negotiations. One of the principal things that I spent my time on was negotiating the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement, which was the largest free trade agreement that the United States had ever done.

BG: At your confirmation hearing to become deputy US trade representative, you talked a lot about the importance of free trade and open markets for America. Can you talk a little bit more about why you think free trade is so integral to the United States?

KB: I think what we need to remember is that, at the end of the day, the United States, although the world’s largest economy, is still only 5 percent of the world’s population. So if you’re an American company, if you’re an American farmer or a rancher, if you’re an American worker, much of your potential opportunity actually lies outside of the United States. The growth of the US economy in many different ways is tied inextricably to those global markets. They are places that we sell to. They are places that we acquire

Karan Bhatia is the head of Government Affairs and Public Policy at Google, a role he has held since 2018. He leads the company’s engagement with a broad array of public policy issues and oversees its involvement with government officials and key political stakeholders in the United States, along with more than 100 other countries. Bhatia previously worked at General Electric for a decade, where he led its government affairs function. Earlier in his career, he served in senior positions at the Departments of Commerce and Transportation. His last role was as deputy US trade representative (USTR) with the rank of ambassador, overseeing American international trade policy with Asia and Africa.

inputs from. Talent comes from abroad and goes abroad. Capital comes from abroad and goes abroad. The clear evidence is that the growth of the US economy means more jobs for people. Improved standards of living have been tied to globalization and international markets. So I’m a pretty unabashed advocate for trade and for globalization. And since being deputy USTR, I’ve had the privilege of working for two companies, General Electric and now Google, that are at the forefront of driving a lot of that globalization.

BG: Delving a little bit deeper into Google and government affairs, where do you see the future of government regulation of AI, especially in regard to the data security and intellectual property concerns that were brought up in the New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI?

KB: I think the regulation of AI is still in its early days. But we have already seen a number of steps taken. Europe has adopted something called the EU AI Act. In the United States, we’ve seen codes of conduct agreed to between the White House and some key technology companies. And we’re seeing a variety of regulatory and policy initiatives in this space around the world. I think that’s good. There is a need for regulation in this space. This is an incredibly powerful technology, and it does need some guardrails around it. But I also think that it is an incredibly exciting technology.

And what you’re seeing policymakers struggle with is: How do we address the risks without slowing it down, undermining it, or distorting the technology in ways that prevent us from

capturing the benefits, like unbelievable scientific advancements that might be made in medicine or in tackling problems like climate change, or just in becoming a more effective economy? I think that one significant issue is going to be: To what extent are there new laws that need to be developed to deal with this? Or do you rely on the existing legal infrastructure?

BG: That’s a really interesting perspective. If you could create the ideal law, let’s say, to improve internet security, what do you think that would be?

KB: Internet security is a great example of what I’m talking about here. You will see there’s a Financial Times op-ed that was published by Google’s CEO, Sundar Pichai, which talks about the role that AI can play in addressing cybersecurity. He clearly acknowledges that there are two sides to this coin—that yes, AI can be utilized by bad actors to strengthen their hand, but it can also be an incredibly powerful tool for protecting users and for strengthening cybersecurity. So, I think a big question for policymakers is: Are there very specific forms or applications of the technology that need to be limited, or do there need to be limits on the ability of that technology to be exported, used, or disclosed? That merits some degree of regulation. But I also think the other side is: How does government policy incentivize people to innovate in this space? How do we pull together a set of government policies that actually do result in AI being a net plus to cybersecurity, not a negative?

Edited for length and clarity.

by Nina Lidar

by Ashton Higgins

A RACE TO THE END OF TIME

From bed nets to insecticides, progress is being made to combat this terrifying rise. But the current generation of anti-mosquito tools is not aggressive enough to mitigate this deadly problem: Bed nets do little to stop Aegypti, which primarily feed on blood during the day, and toxic insecticides have only harmed the environment and driven mosquito resistance. In order to save lives from this man-made and mosquito-driven catastrophe, humanity must embrace its most promising scientific technologies: genetic engineering and Wolbachia bacteria, conscious that we are fighting against both Mother Nature and human nature itself.

Scientists have recently discovered a new ally in the fight against mosquitoes: the mosquitoes themselves. One tactic out of this playbook has been injecting the Wolbachia bacteria, which naturally occurs in over 50 percent of the

world’s species, into Aegypti mosquitoes. When a Wolbachia-infected female lays eggs, the bacteria prevents the progeny from acquiring and transmitting dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Moreover, when a Wolbachia-infected male fertilizes eggs, the progeny will not hatch.

Science: 1. Mosquitoes: 1.

It’s a middle school math teacher’s favorite trivia question: What is the world’s deadliest animal? After images of a hunting tiger or towering gorilla flash through our imaginations, we remember that it is the humble mosquito, whose terrible impact on human lives and healthcare systems is only projected to grow. As carbon emissions continue to rise with no plateau in sight, one oft-forgotten implication of increasing global temperatures is the devastating impact they will wreak on public health, with historically ignored diseases now able to thrive in a new, warmer climate. With global temperatures barreling toward the preferred range for mosquitoes, the number of individuals at risk of contracting malaria and dengue fever may increase by four to seven billion by 2070 relative to 1999.

This threat is already a reality. Take dengue, for example: From 1980 to 1989, there were 1.5 million reported cases globally. Compare that to 2019 alone, when 5.2 million cases were reported. World Health Organization (WHO) officials described this astronomical rise in dengue as a “canary in the coalmine of the climate crisis.” No longer will mosquito-borne diseases primarily threaten equatorial regions—northern cities globally are at risk due to the rise of Aegypti and Anopheles mosquitoes.

Science: 0. Mosquitoes: 1.

“Scientists have recently discovered a new ally in the fight against mosquitoes: the mosquitoes themselves.”

The World Mosquito Program (WMP) has embraced this strategy, releasing hundreds of millions of both male and female Wolbachiainfected mosquitoes across 14 countries and protecting an estimated 11 million people as of December 2022. In the dengue-overwhelmed city of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, the release of Wolbachia-infected Aegypti mosquitoes reduced the number of symptomatic dengue cases by 77 percent and hospitalization by 86 percent. These promising results were replicated in Medellín, Colombia, with an observed 95 percent drop in dengue cases. And in Queensland, Australia, dengue was almost completely eradicated.

Science: 2. Mosquitoes: 1.

As with so many silver-bullet climate mitigation solutions, however, success stories fail to paint a full picture. The cost of mosquito-release programs is nearly $15 per person and far more expensive in rural areas. To blanket the world with Wolbachia mosquitoes, in essence seeking to outcompete the 100 trillion (and counting) existing mosquitoes, is infeasible. Though mosquito releases should be self-sustaining, scientists discovered that the Wolbachia bacteria weakens mosquitoes, reducing their ability to mate and pass on the Wolbachia infection to the next generation. This has contributed to infected mosquitoes failing to establish themselves in Vietnam, Malaysia, and Puerto Rico.

Making matters worse, scientists are fighting a dynamic opponent: Mother Nature herself. Given the rapid rates of mutations among arboviruses like dengue, it is not a matter of if, but when, the viruses will evade the protection brought on by Wolbachia—undoing decades of research.

Science: 2. Mosquitoes: 2.

As such, in conjunction with the more restrained Wolbachia approach, we must also turn to one of humanity’s greatest fears: gene editing. Oxitec, a biotech firm, has proven that its gene-drive technology can kill Aegypti without

the need for continuous mosquito release. Oxitec designed a kill gene that prevents the survival of female offspring but allows male progeny to survive and reproduce, passing on the kill gene. In Brazil, where Oxitec is commercially approved, the gene drive was linked to a 90 percent reduction in mosquitoes.

Even more thrillingly, University of California scientists designed a gene that prevents the spread of malaria in Anopheles mosquitoes. These scientists have set up a lab on the remote island of São Tomé and Príncipe and are awaiting legal approval to release a colony of their modified mosquitoes. Unlike the WMP or Oxitec approach, the efforts on São Tomé do not just seek to kill off a population of mosquitoes but rather fundamentally change the genetic makeup of a species.

Science: 3. Mosquitoes: 2.

Rightfully, these Jurassic-Park-esque technologies beg the classic eschatological question: What does it mean to mess with nature? Hesitancy is already circulating on the airwaves, with one Nigerian environmentalist, Nnimmo Bassey, writing of the stalled São Tomé project, “People cannot consent to what they do not understand. They’re just being used as guinea pigs.” In the Florida Keys, Oxitec trials were

halted after residents raised concerns about the gene-editing technology. Delusion runs rampant, with suggestions that “Bill Gates’ gene-edited mosquitoes” were responsible for an uptick in malaria cases after a release in Texas—a scientifically impossible feat.

Science: 3. Mosquitoes: 3.

While gene editing is an approach that must be undertaken with caution and proper monitoring, there is no reason to believe that modified mosquitoes pose any great threat to our well-being. Dwelling on future doomsday scenarios will do little to alleviate the catastrophe that we are facing today: 700,000 people die annually from mosquito-borne diseases. To not fight for these lives as best we can would perhaps be the greatest injustice humanity can inflict on itself.

The WMP, Oxitec, and University of California scientists sell a great story, and if they can succeed in eradicating dengue or malaria, it will undoubtedly be one of humanity’s greatest triumphs. But history tells us that it will certainly be a battle: As soon as funding for mosquito releases drops—an incessant risk when it comes to diseases classically associated with the Global South—or research into new dengue or malaria strains is forgotten, progress will stall. Wolbachia bacteria are not the silver-bullet, one-and-done

“To not fight for these lives as best we can would perhaps be the greatest injustice humanity can inflict on itself.”

solution that the WMP sells, and gene-edited mosquitoes will have to constantly change to counter the evolutionary pressure of mutating viruses.

Discovering a potential escape hatch for arboviruses should therefore not be taken to imply that other climate-driven diseases can be ignored or that the public health apparatus is sound. Rather, it should be a wake-up call for the world about the human-induced public health crisis at our doorstep.

We must recognize that the best way to mitigate deaths from this crisis is to prevent outbreaks from happening at all. With months of development required for each release of mosquitoes, no known cures for Zika or dengue, and rising global temperatures, there is little time to waste. It is essential to embrace this opportunity to stymie the rise of dengue and malaria—never forgetting that our savvy opponent is armed with millions of years of evolutionary experience. Despite fears of high costs, failures, and mutant mosquitoes, the time is now to embrace the humble mosquito as a technological weapon.

Science: 4. Mosquitoes: 3. For now, at least.

In 2018, Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, passed the Basic Law: Israel—The Nation State of the Jewish People. The law has since been widely derided for its discriminatory nature and codification of the ethnic tensions that have characterized Israel since its 1948 inception. It granted the right of self-determination only to Jewish citizens, declared the goal of Jewish settlement a national value, and established Hebrew as the sole national language, reducing Arabic to a “special status” language. The statuses of Hebrew and Arabic are especially pertinent in the context of larger Israeli society: Linguistic divides deepen the segregation that pervades Israeli municipalities and schools.

Language is foundational to social interaction. It dictates, perhaps more than any other facet of everyday life, one’s ability to function within a social network. Entrenched deeply within both Israeli ethnic communities and the Israeli education system is a stark lingual disparity: Hebrew is prioritized over Arabic. Instead of supporting all of its citizens, Israel actively operates against its Arabic-speaking populations by facilitating severely imbalanced cross-language comprehension between them and their Jewish counterparts. Moreover, the onus has been placed on the former group to accommodate and conform to the standards of the latter—resulting in

inequitable opportunity, entrenched bias, and media echo chambers that, among the native Hebrew-speaking majority, favor an Israeli nationalist perspective. Israel must reverse the tenets of the 2018 Nation State Law, reinstate Arabic as a national language alongside Hebrew, and fund and mandate the equal education of both languages in all public schools.

One of the starkest examples of systemic discrimination against Arab Israelis is visible in the nation’s education system. About 1.6 million students are enrolled in Israeli primary and secondary schools, but, as of 2016, only 2,000 students total attended joint Jewish-Arab schools. Instead, students overwhelmingly attend homogenous schools with curricula distinctly informed by ethnicity. In schools for Jewish Israelis, classes are in Hebrew; Arab students generally receive their education in Arabic. While learning Arabic is not mandatory for Jewish Israeli students, for Arab students, learning Hebrew is now required. The resulting disparity in language proficiency is staggering: About 90 percent of Arab citizens are fluent or near-fluent in Hebrew, compared to a meager 6 percent of Israeli Jews who speak Arabic. In a nation that is roughly 74 percent Jewish and 21 percent Arab—excluding the approximately 5 million Arabic-speaking Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied territories of Gaza and the West

Bank—these statistics indicate an undeniably two-tiered language system.

The composition of Israeli municipalities also reflects both the state’s and the major ethnic groups’ antipathy toward facilitating cross-cultural relations and ethnolinguistic equality. Despite the substantial size of Israel’s Arab population, ethnically integrated municipalities are remarkably uncommon. A mixed city in Israel is characterized by minority Arab enclaves within a majority Jewish municipality. As it stands, there are only eight mixed cities in total—or seven excluding Jerusalem, where the Arab population primarily lives in annexed East

“To now require all citizens to learn only Hebrew while leaving Arabic by the wayside represents a slap in the face to Israel’s already second-class Arab population.”

Jerusalem and is excluded from Israeli citizenship. Moreover, only 10 percent of Israel’s Arab citizens live in these mixed cities. The remainder of the 134 recognized Arab municipalities in Israel are not mixed. Similarly, the majority of the nation’s Jewish population lives in predominantly Jewish cities. Unsurprisingly, in Jewish cities, people speak Hebrew, and in Arab cities, they speak Arabic. Visual markers of this linguistic difference pervade the city: In Jewish and mixed cities, the names of stores are written primarily in Hebrew, often with an Arabic inscription underneath, while the opposite is true in Arab cities. Street names and signs display a similar pattern.

The stark separation of Jews and Arabs and the attendant inequality between Hebrew and Arabic have caused ethnic fracture and deepened ethnic resentment. Changes to Israeli domestic law regarding language could reverse these trends by facilitating understanding between Jews and Arabs.

Such understanding has been sorely lacking even at the best of times, but the need for cross-cultural comprehension has been sharpened by the war in Gaza. Since the beginning of the war, Hebrew-language Israeli outlets have been near-uniformly pro-Israel. Even liberal Israeli publications such as Haaretz have largely focused on the trauma of October 7 and the return of the Israeli hostages. Mainstream Hebrew-language media often ignores the atrocities in Gaza and does not include the perspectives of Gazans; most allusions to these perspectives are oblique appendages to an Israel-centered narrative. If Israeli Jews’ Arabic language comprehension were better, the likelihood of Jewish engagement with Arabic reporting would be far higher. Such exposure could engender a greater understanding of Israel’s war crimes and potentially soften hardline stances on the war—which, in domestic Hebrew media, is largely framed as an appropriate and vital response to the events of October 7.

Indeed, Arab citizens within Israel are overwhelmingly opposed to the nation’s military

“Segregation will self-perpetuate for as long as the status of language continues to represent ethnic hierarchy. ”

for instance, has a significant number of native Spanish speakers—12.5 percent of the population—but conducts federal proceedings only in English and mandates that English be taught in public primary and secondary schools. It does not mandate Spanish language education. Many more countries across the world have adopted similar systems to manage multilingual populations. So why, given these similarities, should Israel receive criticisms from which others appear exempt?

The difference stems from Israel’s unique situation—in particular, from the recency and character of the nation’s establishment. In what is described in Arabic as the Nakba, or the “catastrophe,” the 1948 formation of Israel violently displaced around 800,000 Palestinians, some internally and others into surrounding countries and occupied territories. About 60,000 people in Israel today were born in 1948; in other words, living memory recalls a time when Hebrew did not reign. To now require all citizens to learn only Hebrew while leaving Arabic by the wayside represents a slap in the face to Israel’s already second-class Arab population. While a single national language is conducive to establishing equal rights and opportunity under one government, enforcing the domination of a language not natively spoken by a significant proportion of the population generates inequity and erodes culture.

actions in Gaza. While their ethnic ties to Gazans no doubt contribute to this sentiment, it is bolstered and informed both by their own systemically enforced abjection within Israel and the widespread consumption of Arabic-language media. It is too late for voting-age Israelis to receive adequate Arabic language instruction during this war, but the one-sidedness of domestic Hebrew-language coverage demonstrates the necessity of bolstering Arabic instruction for future generations.

Some might argue that the emergence of a dominant language under a unified government is necessary and inevitable. The United States,