Poem with Cat

Leone Brander

They say writing is lonely work and that is mostly true. I am mostly lonely. 11113`` But I am not ever completely alone qwq11, because as I type, even now, my sweet orange tabby, rescued from ``1qq some frozen `` q field, now dozing on our couch, 23a rests his head on my lap, on my wrist, on the keys. `qq211` ``121 qaqq1` qw `qqwwq `32

unrbrushfire.org

@nevadabrushfire

l iterature & a rts

b rushfire

j

e dition 7 6 v olume 2

ournal

SPRING 2024

EDITION 76, VOLUME 2

UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO

Copyright © 2024 Brushfire and its individual contributors.

All rights reserved by the respective artists. Original work used with the expressed permission of the artists. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

The opinions expressed in this publication, its associated website, and social media are not necessarily those of the University of Nevada, Reno or of the student body.

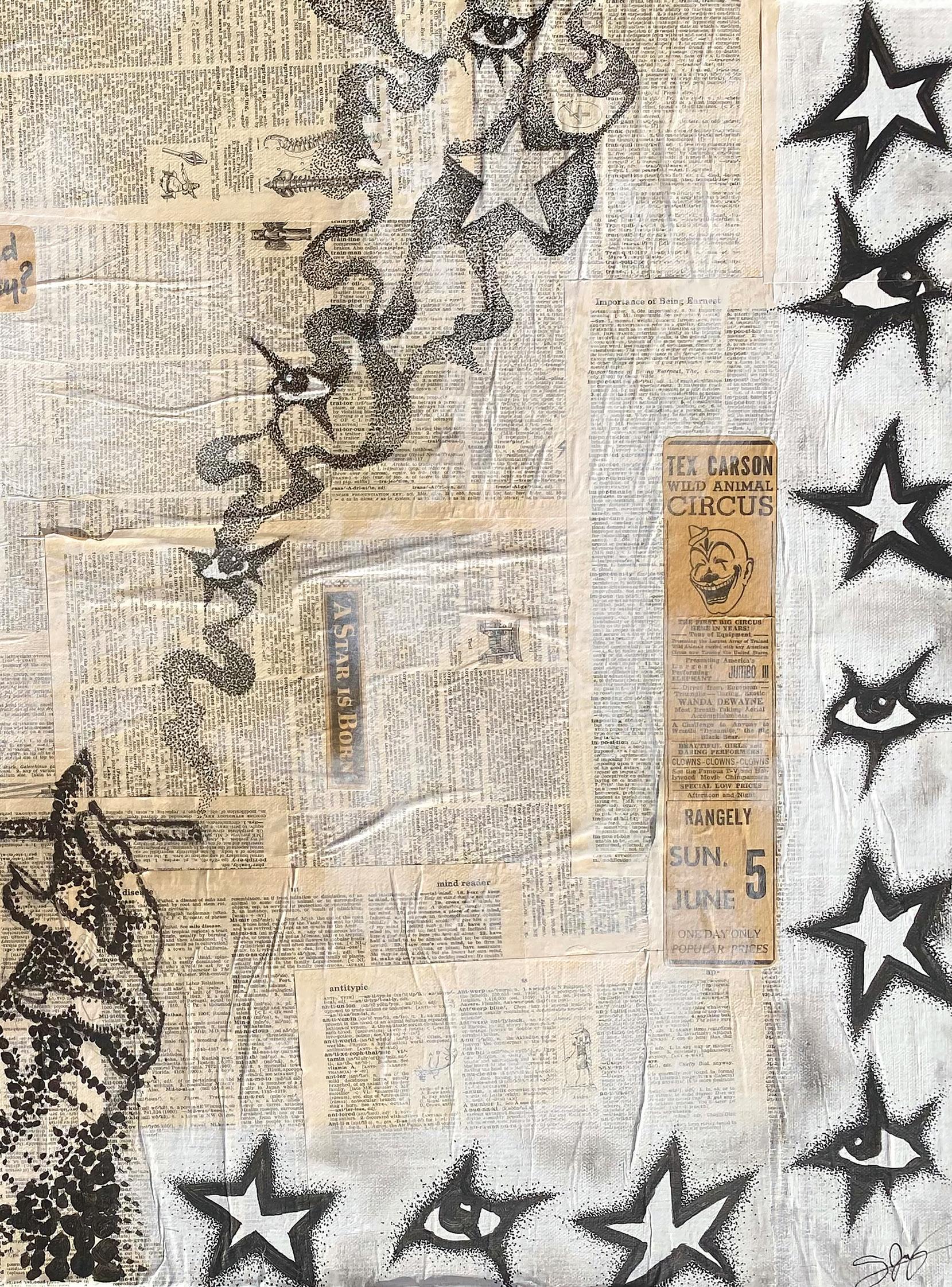

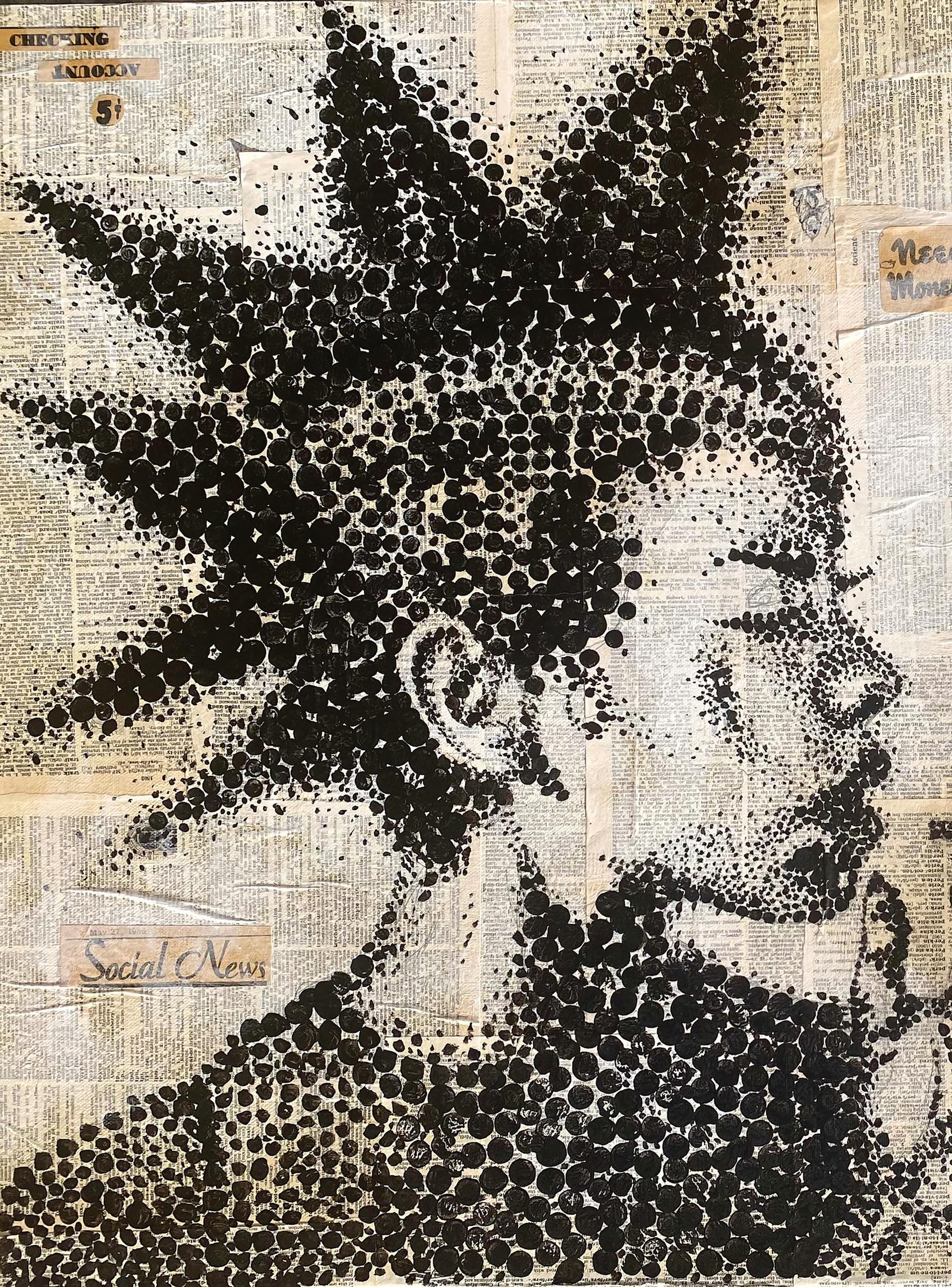

journal layout cover art artist Brushfire Staff digital puberty 2011 Brooke Germain : : :

E ditor ’ s N ot E

Throughout my time at Brushfire, one thing has remained constant: the need to justify the existence of literature and art publications. We are currently funded by the ASUN, who largely misunderstands the function journals like Brushfire provide for universities and cities at large. Why do we need funding? Why do we need to pay for printing? Why do we need to exist at all? Out of all the student services that ASUN funds, a literature and arts journal may seem like an unnecessary luxury. However, Brushfire provides one of the most important civic functions: inspiring sympathy. In a divisive culture, it is the ultimate sympathetic practice to support Brushfire (and other publications) because in the process of reading and creating we broaden our understanding of ourselves and others. We become more compassionate because, through these words and visuals, we understand new perspectives on the human experience

Nothing could be truer for this edition of Brushfire which encapsulates the complete circle of life in all of its frustrating grotesqueness and heartfelt transcendence. I hope that this journal provides insights into your life so that you can take care of yourself and others. I hope that you laugh and cry and slam the book in frustration. I hope that you tear the pages out and hang them on your wall. I hope you memorize a poem and recite it to yourself when you are in need of answers. Most importantly, I hope that you learn and share what you have learned with others. We print this journal because it is meant to be shared, so when you have finished it, pass it along to your friends and family because everyone could benefit from a little sympathy.

— Abigail MacDiarmid Executive Editor

t abl E of C o N t EN ts

Brooke Germain

Skylar Jory

Adrianna Pereyra

Anna Newman

Christine Wilson

Skylar Jory

Sofia Lombardo

Christian Kubik Cedeño

Luke Rizzotto

Arianna Pride

Juliette Northam

Christine Wilson

Ai Ana Richmond

Juliette Northam

Brooke Germain

Sherry Shahan

Dorothy Moss

Amuri Morris

Sherry Shahan

Ana Cruz

Jason Mennel

digital puberty 2011

Nature’s Reaping

Indulge

Spring Barn

Pity the Clown

The Performer

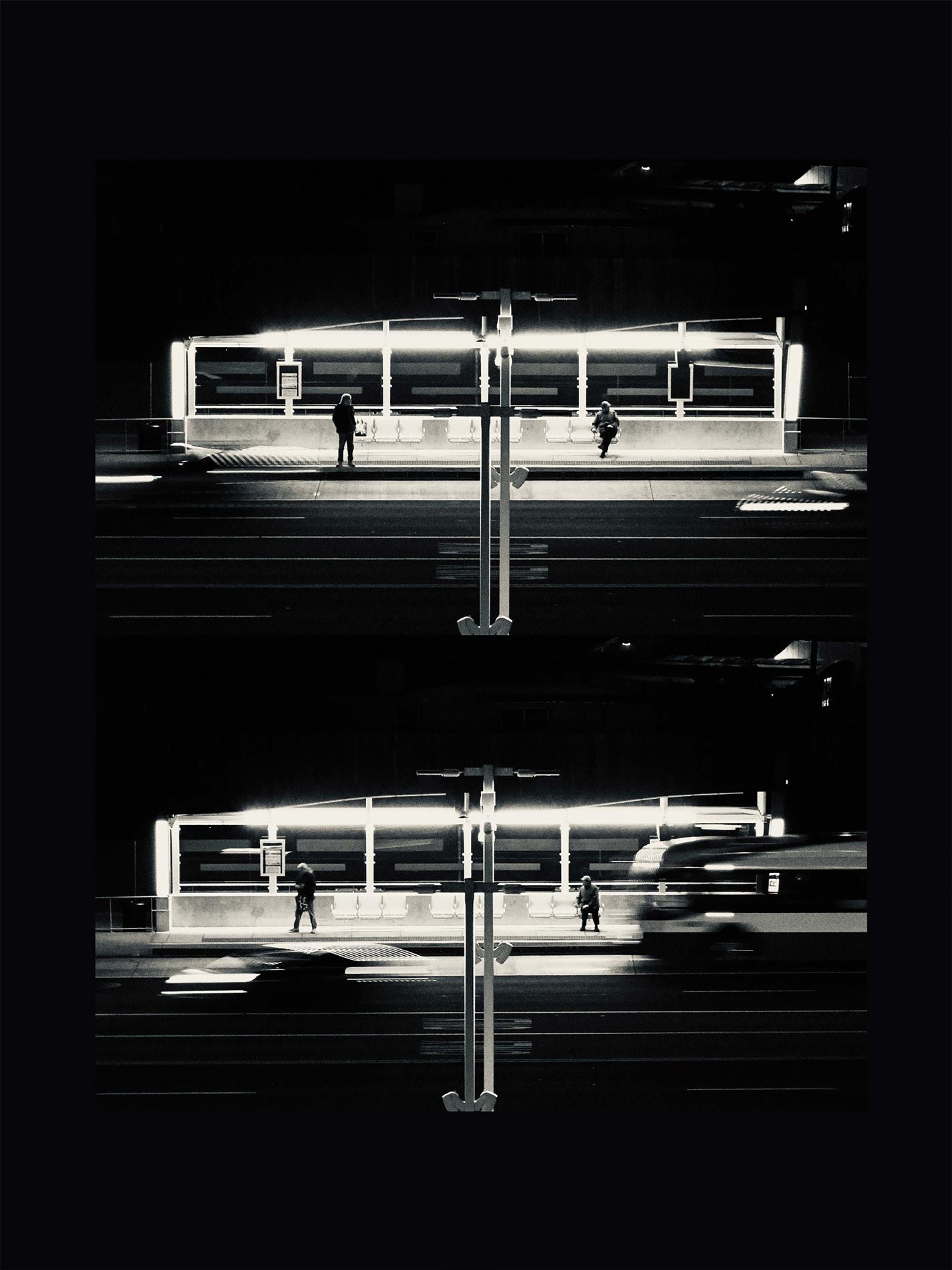

6th Street

Friends For Life

Eternal Sunset Poster

Waiting On My Way

The Organic Rely On The Inorganic

Respect and Protect Our Native Wetlands!

Let The Thoughts Be

Heaven Sent Lamprey

Memory

Eden Our Lady

Our Town

My Hero

Meet You Under the Stars

visual

Cover 7 8 15 16-17 18-19 20 27 28-29 30 32-33 35 37 39 40 45 46 49 50-51 53 55

t able of c ontents

Zoey Cornelius

Ken Cathers

Laurie Alcantra

Lily Finch

Jordyn Becker

Bharti Bansal

Emily Eddins Diana Quintero

Madeline Gauthier

Ai Ana Richmond

Aiden Sosa

Halley Fehner

Ned Weidner

prose

The Guilt in my Grief

Island Sunrise

Summer at the Beach

Existence

What Might Have Been

The Apple on the Tree

Poem with Cat

Tapeworm

The House at the Edge of the Sea

Raining Thunder

Landed

The Silence of Wild Things

Mold malice

poetry

6 16 19 29 31 32 36 45 Back Cover

Leone Brander

9-15 21-26 34-35 39-42 46-47

Mold

Zoey Cornelius

Beginning wrapping itself under my bed-

Starting with an orange that must have made its way there

After I dug my fingers in right before I realized That I could not bring myself to eat it.

The growing smell of aging wooden floor boards and decayIt spreads its white wings over what was once new Suffocating the air around it.

It moves to take out boxes

And half drinken soda cans, Frost touched skin

Slowly spreading like sweat down my foreheadOn my bedroom floor

Through the wave of old carpet.

I stare off from my bed, And if I concentrate hard enough I see it grow, and grow, and encompass more, and more-

With a million shades of green

Some blue and black, A touch of snow and powdered candy.

Now I lay, and I wait for it to circle around me

Creeping up on me when I close my eyes Before it enters my lungs ever so slowly, Wrapping all around me.

6

Nature’s Reaping Skylar Jory 7

Indulge

Indulge

8

Adrianna Pereyra

Tapeworm

Madeline Gauthier

The tapeworm is moving again. Jenna can feel him slinking beneath the fabric of her skin, just as he had been earlier this morning. She nervously looks around Dr. Reed’s office, trying to find something to distract her, something else to worry about, and her eyes settle on the clock over his head. Her lunch hour is almost up.

“Jenna?” Dr. Reed asks, waving a hand in front of her eyes, “Are you listening to me?”

Jenna’s eyes snap back to his face. “Sorry doctor, what did you say?”

Dr. Reed rolled his eyes. “I said, why are you here today? I take it your granddad suggested it may be time for a referral to a psychiatrist?”

Jenna bristles at the mention of her grandfather. She knows he and Dr. Reed met every Sunday to play golf, but she didn’t know they talked about her. Her grandfather was always airing out her private business, and she resented the invasion into her private life. What had he been telling the doctor?

“No, actually. I think I have a tapeworm.”

His eyebrows raise. Jenna runs a nervous thumb over her opposite wrist, her skin pulled tight as a tarp over the place where the tapeworm has come to rest. The silence unsettles her.

“A few days ago, I got food poisoning after I ate at a restaurant, and I think maybe the chef who cooked my dinner didn’t wash his hands or something. I looked it up,” she says hurriedly as the doctor tries to cut in, “people can get tapeworms if someone doesn’t wash their hands before they cook.”

“Are you finished?” he asks, a dismissive smile lazing across his face. “My dear, you do not have a tapeworm. It’s the 21st century. That’s like saying you think you’ve caught the bubonic plague. Now tell me, when was the last time you had your period?”

Something hot and venomous burns in Jenna’s stomach, but she says nothing. Instead, she presses her anxious thumb on her wrist, hard, and feels the worm’s now familiar wriggle. She knew it. He’s still there.

Doctor Reed clears his throat and lowers his eyes back to his clipboard.

“Listen honey, your granddad is like family to me, so I’m just going to give it to you straight. It’s normal for women your age to feel nauseous or tingly, especially when it’s that time of the month. So why don’t I give you a little anti-nausea pill, and you promise me not to work yourself up anymore,” he says, already reaching for his prescription pad.

9

The movement intensifies under Jenna’s thumb. Maybe the pressure is suffocating him. With pleasure, she imagines squeezing the air from his tiny lungs until they collapse on themselves, killing him and ending any need she has for the doctor’s help.

“And I don’t want to hear any more nonsense about a tapeworm, alright? You’ll scare your granddad with that kind of talk. He’s awfully squeamish, you know.”

Jenna obediently takes the prescription from Dr. Reed.

“Thanks doctor,” she says weakly, “I’ll let you know if anything changes.”

“Sure, sure,” he says, waving his hand, but Jenna has already left the office.

On the bus ride back to work, she tries not to follow the tapeworm’s progress up the inside of her arm, instead choosing to stare determinedly out the window. Her prescription burns like a smoking gun in her hand. #

The line at the pharmacy is long, even for a Saturday morning. A shriveled old man has been yelling at the single pharmacist working for fifteen minutes now with surprising gusto. The people in front of Jenna are growing noticeably more fidgety, their eyes darting between their watches and the paper sign taped to the wall announcing that the pharmacy will be closing for an hour at noon.

After a while, the man finally retreats, and the weary pharmacist begins to help the rest of the customers. Jenna’s eyes remain glued to the paper sign, reading and rereading its message. The pharmacy closes at noon so the pharmacist can eat lunch. Reflexively, her stomach gurgles, and the woman in front of her peeks worriedly over her shoulder. Jenna gives her a halfhearted smile as she reaches up to tighten her ponytail with shaking hands.

She hasn’t been able to eat since she left Dr. Reed’s office yesterday. That’s not to say she hasn’t tried, of course, but the few measly bites she’d taken from the granola bar in her purse only seemed to energize the tapeworm. He has been crawling beneath her scalp all morning, and no amount of scratching has alleviated his persistent itch. Jenna was beginning to come to terms with the fact that her plan to starve him out has only served to make him smarter and more adaptive. Without the secondhand meals from his host, he’s been feeding on Jenna herself.

“Next!”

Jenna jumps as the pharmacist yells. No one else is in front of her anymore.

10

“Hi,” Jenna says, smiling warmly. The pharmacist holds out a hand for her prescription in response.

“Right, here you go,” she says, digging the paper out from the bottom of her purse. On the off chance that Dr. Reed wasn’t completely wrong, she’s decided to fill her prescription anyway. Maybe some chemical in the pill is toxic to tapeworms.

The pharmacist gives the paper a cursory glance, then disappears between the tall shelves stacked with pill bottles. Finally alone, Jenna allows herself to fall apart. She digs her nails into the tight hair of her ponytail, rubbing so hard that her head shakes.

Jenna feels the tapeworm run his tongue playfully over the edge of her skull in retaliation to her scratching. She knows it’s all a game to him, invading her body, drinking her blood. She can just imagine his gluttonous little form splayed across the shell of her cranium, fat with her own physical makeup. Frustrated, she grabs a chunk of hair and pulls upward. That’ll show him, she thinks.

When the pharmacist returns, she finds Jenna gingerly rubbing a new bald spot next to her left ear. A clump of hair, bound together by a bloody piece of skin, lies limply like leftover spaghetti at Jenna’s feet. The pharmacist doesn’t bother asking. She’s already seen worse today, and the pharmacy closes in fifteen minutes anyway.

“Anti-nausea pills,” she says, setting the bottle on the counter. “Do you have vertigo or something?”

Jenna shakes her head.

“It’s from my period. At least, that’s what my doctor says. I think I might have food poisoning. Or something worse.”

The pharmacist nods distractedly, typing information into the computer.

“Well, I hope these get rid of the nausea, but like I always say, ‘better out than in’. If it is food poisoning, that is. Cash or card?”

Jenna adjusts her ragged ponytail to hide her new bald spot and reaches for her purse. The pharmacist takes Jenna’s credit card, ignoring the bruise festering into a sickening yellow in her elbow.

“Feel better,” the pharmacist says as the transaction goes through.

Jenna smiles again before turning to exit the pharmacy, leaving the clump of her hair trampled in her wake. The pharmacist watches her go and shakes her head. Something is seriously wrong with that woman, she thinks. #

“Better out than in,” Jenna mutters to herself. It’s become her mantra

11

since she left the pharmacy with her useless anti-nausea pills in tow. Upon arriving back in her apartment, Jenna walked calmly to her bathroom and flushed the pills down the toilet. With her new plan, she wouldn’t be needing them anyway.

She’s been watching herself in the mirror, watching the way the tapeworm has migrated from her scalp down to her forehead. It sickens her, the way her skin bubbles and deflates with his every step, the way he traces the arch of her eyebrow. He thinks he owns her, like a piece of antique furniture or a real estate holding. She wants him evicted, immediately.

Better out than in.

Jenna feels the tapeworm slow down, then come to rest in the divot of her left temple, comfortable and unsuspecting. Now is her chance. She reaches into the shower for her razor, then unhooks the blade from the rusted purple head. This is going to hurt, and she knows it. Her reflection stares back at her from the mirror, flecks of toothpaste marring its surface. She can’t recognize the woman with the bald spot and the sallow skin. She wants herself back. Without hesitation, Jenna places the edge of the blade at her temple and begins to carve along the ridge of the tapeworm’s outline. A thin ribbon of red forms on her skin behind the blade like a gory shadow as she cuts. With each passing second, more blood condenses on the surface of her face until it drips down and pools in her ear.

Jenna gets close to the mirror, searching, searching, until— Yes. She sees him.

A vengeful smile scrawls across her bloodied face. Without taking her eyes from the tapeworm’s now-exposed body, Jenna reaches into her makeup bag for her tweezers. With the precision of a surgeon, she grasps tightly onto his awful, squirming tail and pulls him screaming from beneath her skin.

She holds him for a moment, watching as he tries fruitlessly to free himself from the tweezers. His ugly mouth, open in a perpetual squeal, is smeared with her blood. She pinches him harder and laughs as he bares his needle-like teeth.

“Now who’s afraid?” she asks, and the tapeworm shudders wetly in response.

Jenna walks confidently to the kitchen and dumps him, still writhing viciously, into a plastic container.

“I know someone who would love to see you,” Jenna says to him, and shakes the container for good measure. “How can he argue with me now?”

12

The tapeworm throws himself against the side of the container in rage.

Jenna shakes him into submission again, then picks up her phone to call for a taxi.

Like the pharmacy a few hours ago, the hospital is very busy. But instead of demurely waiting in any lines, Jenna walks directly up to the front desk where a disinterested receptionist is methodically shredding a sticky note and speaking on the phone.

“Last name of the patient you want to visit?” the receptionist asks as she puts the receiver down.

Jenna slams the plastic container on the desk. The tapeworm cries out anemically.

“I need to see Dr. Reed,” Jenna responds.

The receptionist looks up, first at the tapeworm in the container and then at Jenna’s mangled face. Her mouth drops open in a scream that echoes off the cavernous walls of the reception area.

“My God, what have you done?” she says, eyes flickering between the worm and Jenna in an endless loop, “What have you done?”

“Just bring me to Dr. Reed, please.”

The receptionist snatches the phone back up and quickly dials a number. Within moments, a nurse appears pushing a wheelchair. Jenna doesn’t resist as the nurse and the receptionist force her into the chair and begin dragging her toward the emergency room. Instead, she laughs at the urgency of the medical staff. Didn’t they know she had already cured herself, no thanks to them?

Everything seems to move around her so quickly, blurring at the edges like an impressionist painting. Nurses in scrubs grimace at her, their faces contorted into cartoonish Halloween masks, before her wheelchair is pushed past them rapidly and they melt into the rest of her surroundings. Her ear is still full of crusted blood, so she uses the end of her pinky to dig it out. It looks like a crescent blood moon beneath her nail.

Before long, she is being pushed into the familiar blandness of Dr. Reed’s office. A young man is sitting on the examination table, and the doctor is stooped over his shoulder with a stethoscope.

“Doctor,” the nurse says, “I’ll take over your patient. You need to see this woman instead. She asked for you.”

At first, Jenna thinks Dr. Reed doesn’t recognize her. He isn’t up to any of his usual tricks; he does not smile or offer an anecdote about her grandfather.

13

In fact, this is the most reserved she has ever seen him. After a moment of appraising her, he speaks.

“Jenna, what happened to you?”

Jenna cocks her head, hiding the gruesome mess she’s made of herself, and grins.

“It might be better to ask what happened to the worm.”

The doctor sighs, evidently displeased that she hasn’t listened to him. He turns back to his other patient, helping him up from the bed and leading him to the nurse. They leave hastily, the nurse’s horror-stricken features flashing across the window momentarily before disappearing down the hallway.

Dr. Reed stands before Jenna and takes in her appearance, more fully this time. His eyes widen as he progressively comprehends the bald spot in her hair, the blood still dribbling from her head. Finally, he crouches beside Jenna and uses a gentle, gloved thumb to brush over her gaping temple. She tries not to flinch at the prodding of her tender flesh.

“I cut the tapeworm out. You didn’t believe me, but I cut him out and brought him here to show you that you were wrong.”

She shoves the container into the doctor’s hands. He glances down at the screaming, writhing form of the tapeworm, then whips around to wretch drily into the tiny trash can beneath his desk. Jenna’s eyes light up with sick satisfaction at his broad form, seemingly unshakeable, felled by her actions. “Jenna,” he says breathlessly, still heaving over the trash can, “that isn’t a tapeworm. You’ve cut a vein out of the side of your head.”

Confusion washes over Jenna, replacing any vindication she had felt before. What is he talking about? The bloody mass curled at the bottom of the container is clearly a tapeworm. She can see the segments of his body, his millions of tiny feet. If she cut him open, it would be her muscle mass, her blood, lining his stomach. The poisonous feeling of being disbelieved crawls unpleasantly up her throat.

“How can you say that?” Jenna screams. “How can you still not believe me when I brought him to you?”

Dr. Reed just shakes his head and reaches for the tools on his desk, staying well away from Jenna’s flailing arms.

“It wasn’t food poisoning, and I wasn’t even on my period! If you had just listened to me—”

Dr. Reed grabs Jenna’s chin with one hand and wrenches her head to the side, exposing her bloody temple. With his other, he cracks the lid of the container. The tapeworm gives a triumphant gurgle that is drowned out by

14

Jenna’s renewed screaming.

“What are you doing? You’re going to let him escape!”

“Jenna, I can’t in good conscience let you keep living this delusion. Your grandfather would never forgive me if I didn’t do what was best for you.”

The doctor plucks the tapeworm from the container and places him, wriggling victoriously, back into Jenna’s temple. His fingers are painful around her chin, and she can only yell in agonized disbelief as he uses a needle and thread to sew the worm back into her.

When it’s all over, Jenna is still. Silent, scalding tears drip down into her mouth as Dr. Reed washes his hands at the sink.

“You put him back,” she whispers, and her voice breaks.

“My dear,” the doctor says calmly, lathering soap between his paunchy fingers, “your body parts are of more use to you inside than out.”

The tapeworm snuggles against her skull contentedly, overjoyed at being returned to his place of residence, and Jenna winces. Dr. Reed dries his hands and pivots to face his patient.

“How do you feel? Are you ready for that psychiatry referral we talked about?”

Jenna strings a smile across her face like a broken necklace. “No need. I feel fine. Thank you, doctor.”

END

Anna Newman

Spring Barn

Spring Barn

15

malice

Ken Cathers

violence is a language learned from birth

that casual slap on the head an arm bent back it is the first phrase remembered a rock thrown in the dark

a complex syllable a curse hissed

how easy the rhythms come to us, the smug cadence of lies

how helpless we are against it

hand slammed in a car door

the pain naked beyond words

catch that quick glint of malice in your eyes

16

17

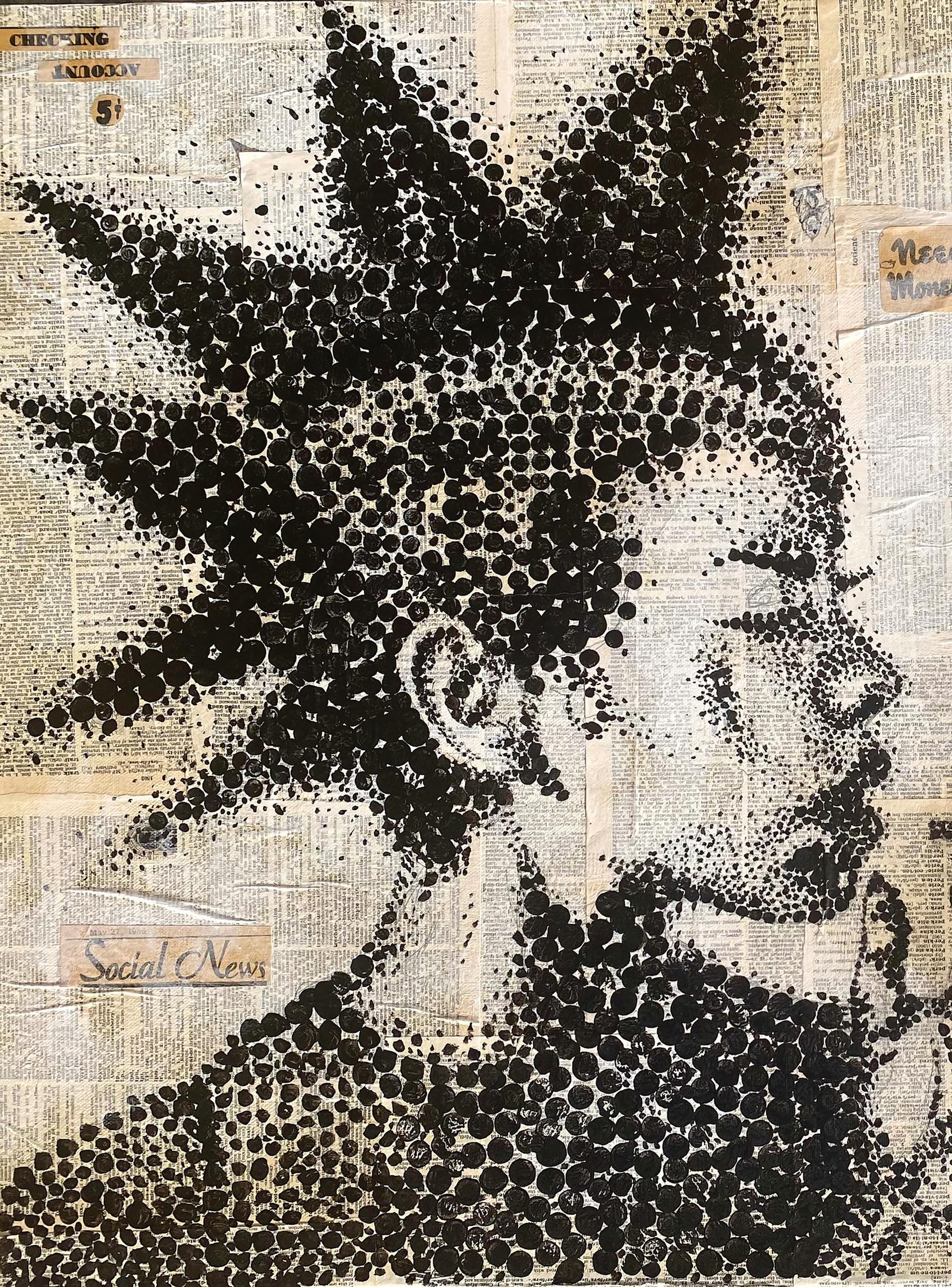

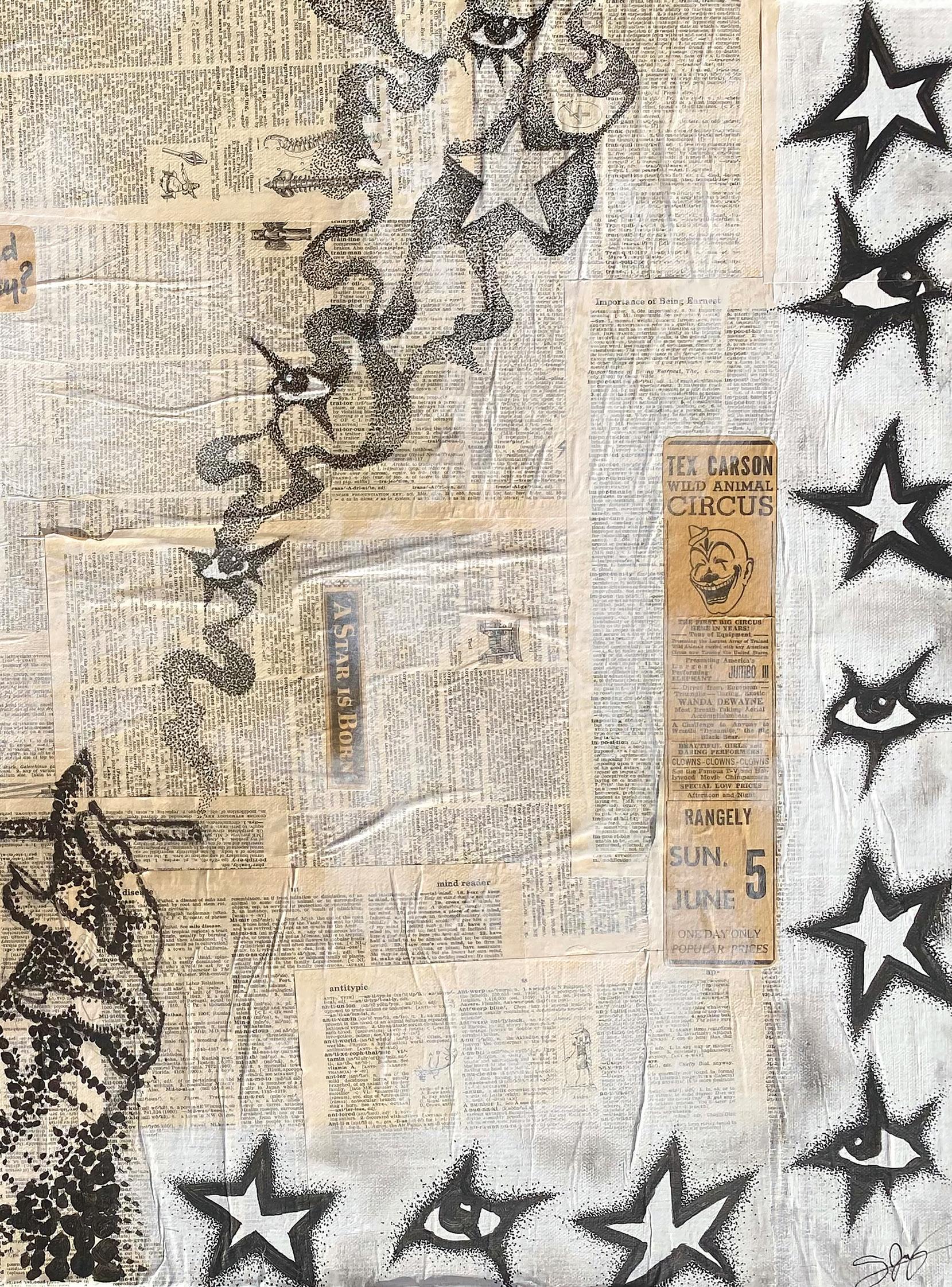

Pity the Clown Christine Wilson

18

The Performer Skylar Jory

The Guilt in My Grief

Laurie Alcantra

You went down not with a scream, but with a whisper. The strength in your silence and the guilt in my grief. With the actions of a mother, and the words of a sister. My denial is no longer suspended in disbelief.

Unshed tears, an inconvenience in someone else’s favor.

Your daggers of deflection, a looking glass into your mistakes. The bitterness in my spite, like poison I should savor.

The cracks in your mask, your civility finally breaks.

The easy relief in death, and the torment of being left behind.

I’m a novel in your life while you’re a footnote in mine. A connection with you, forever I’ve pined.

The summer before you left, the last time the stars aligned.

Forever a stranger in my pictures, my forgiveness with nowhere to go.

I’ve been told I act just like you, but I guess I’ll never know.

19

6th Street

20

Sofia Lombardo

The House at the Edge of the Sea

Ai Ana Richmond

Percy is always surprised at how versatile grief is. There are days with the movie-type breakdowns on the kitchen floor with snot smeared across both sweater sleeves. There are days where the grief is a small pebble of anger nestled deep in her chest, right where her heart is supposed to be. There are days when things feel almost like Before, until a waft of perfume or the tilt of a stranger’s chin leave her breathless with wanting. And then there are the days that stretch the silences long, wearing them thin against the press of the wind. These are the days when Percy thinks of the war widows, wandering the crags of the cliffs and mourning the loss of someone decades before. She wishes she could drape herself in black lace for the year, a stark warning to everyone around her. Fragile, she’d read. Handle with care.

Today is one of those days. Wallowing in it, as tempting as it is, means it only clings to her longer. Drowning in want and frustration so thick it felt like she was breathing mud. There are two viable choices: distraction– that cheap, tinny, circus-like thing that doesn’t do justice to the tenderness of her– and going for a walk along the water.

The lane curves, hugging the coastline. The bushes are nothing more than scruff here, prying their roots into the rock to gnarl against the wind. Percy’s whole being feels like a deep bruise, like the slightest touch aches. It’s odd to find her body perfectly fine and functioning, cheerily demanding food and going stir-crazy as her mind twists itself into knots, wringing out everything until there’s an echoing sort of emptiness.

But she’s here and she’s bloody cold, so she must be alive. She’s grumbly and disgruntled, resentful of leaving her nest of a bed to brave the blustery day threatening to strip the skin off her bones. Why, she has no clue. Yes you do, a little voice whispers. You know it’s good for you to leave that house. Nostalgia is a dangerous thing, she’s learned. The stuff of love letters and childhood dreams, she’d thought. But now she’s living amongst a shrine to a life from Before. The photographs in the hall, still in her nan’s garish frames, outdate her by decades. Faded faces she should know grin back every time she bumbles down the hall. Lonely, almost, without her recognition. Yeah, right. Nostalgia claimed more lives than loneliness ever did.

She stops at the shop on the corner, grabbing a packet of crisps and some chocolate she definitely doesn’t need and definitely doesn’t care about not needing. The cold cuts right through her in that rickety old house where the heat leaks out like a gap in a dam. A wee bit of padding around her middle wouldn’t hurt at all, not in the misery of November.

#

It’s blustery again today, but Percy doesn’t mind. The coast is always

21

bare on days like this–even the gulls are seeking shelter elsewhere. The loneline clings to her like a cloak, gnawing at her in the early hours when shadows stretch short and even the owls are silent. But on days like today, it became a thing of comfort. The solitude cleared the cobwebs out from her lungs, exhaling dust and soft, broken things into the mist and crags.

Percy laces her boots tight-tight-tight, not quite pinching. Her wool sweater is moth-eaten by now, elbows worn bare and patched time and again. Wool, down, cashmere. If you lived up here, you knew how to keep the bitterness out– natural fibres and strong tea were usually the best methods. The path stretches out in purple-grey of new bruises and the tattered MISSING WOMEN signs in the supermarket window. It is slick, sheer cliffs dropping into the pounding sea below. Not many people walked this even in the summer; the snarls of lichen clinging to the cliff face was deterrent enough. It was three winters ago the police were here, dredging the brutal current for weeks. Nothing was found. Percy still thinks of it, sometimes. How long does it take for flesh to decay in saltwater? Would it still be recognisable, hair spread veil-thin across the surface of the water? Or would it just be a collection of bones, rolling along at the bottom of the sea with the cobbles and kelp?

Things sneak up on you in the mist. Percy knows this. It’s still surprising to see the hunched figure of a woman on the lookout bench. She keeps an eye on her as she draws closer, fingers jammed into mittens jammed into pockets, beanie jammed onto her head.

The woman is blind, Percy notes. Eyes the colour of sea glass, peering out from a lined face. Percy thinks of crabapples in the autumn. They dry and shrivel up on the trees long after the leaves have dropped, coarse and leathery and brown in the snapping air.

Her hair is wispy, fanning out from her bare head. Cobwebs, Percy thinks again. Bare knuckles, swollen and cracked with time, are pressed into her lap. This woman should be frozen in place, dead like the homeless folk Percy sees the police cleaning up from time to time. Exposure, they always say. Not “drug overdose”, or “decades of abuse” or “the weight of a system that has repeatedly failed them”. Convenient, packaged into three syllables that fail to convey an entire life.

This woman should be dead, sitting like a stone in the biting cold, but her face turns to Percy as she passes by. No acknowledgement, of course. People here are cut from rough cloth and hemmed with hardship. Percy knows. She’s one of them. But no one should be here in November with a bare head and hands. Percy stops.

“Hello,” she mutters, squatting on the bench. It’s narrow. The woman is in the middle and makes no effort to make space. Percy’s bottom goes numb in a matter of seconds.

22

“Hello. What do you have for me?”

The woman’s voice is hoarse, like crows and the rough barking of the tides against wood.

Percy blinks. Tugs off her beanie, tries to press it into her hands.

“No, no,” she says. She smells strange, almost like the sea: like rich earth and salt. Like death. “That is tied to you. Something less.”

Percy blinks at the woman, who has resumed her sea glass stare into the mist. Her hands scrabble through her pockets: a marble, an old receipt, a linty stick of gum. A knot of wood that had caught her attention on a prior wander. She turns it over in her fingers. The whorls are familiar– she’s polished the wood with the grime from her hands, rendering it smooth with her countless worries.

“Here,” she says, dropping it into her lap.

The ricepaper skin on the woman’s hands crinkle as she runs her fingers over the bark. A dry laugh escapes like smoke through a cigarette.

“Such anxiety pecking at you,” she says, delighted. “Your burden distracts from my own. Stay.”

Percy sits properly, shifting to be closer than she’d like to the woman. She jams her hands in her pockets again, knocking elbows. The cold leeches into her layers. Percys tucks her chin a little closer to her chest.

“Where do you want me to start?”

“Wherever feels right, I suppose.”

Percy sighs. Vague answers seem to be inescapable these days.

“Well,” she began, pressing tight against herself to cling to her own warmth.

“I don’t have much to say.”

“Yes, you do.” The old woman clicks her tongue. A crow cocks its head, hopping closer to inspect the morsel caught between her fingers. Its stark blackness is a contrast– by November, the rain has rinsed the colour out of everything. It’s all shades of greys and browns and lichen greens.

Percy watches as it takes the food and glides into the mist.

“Well,” she says again, recrossing her legs and wedging her hands between her thighs. “We moved into my nan’s house a few months ago after everything happened.” She exhales, watching the plumes of her breath dissipate in the cold air. “We used to spend time here in the summers as kids, roaring up and down the beaches. Get ice cream on the way home even though the wind blew the warmth right out of our bodies, even in August.”

The crone dips her chin in response.

“Things change, though. Only constant in life, right?” Percy’s laugh is nervous.

“That and death, you’re right about that. But I don’t need to tell you that love, do I?”

Yes. Percy is familiar. Her reassuring smile to the probing eyes is lost, which is fine. It was watery anyway.

“Yeah, so I moved into the old house in July.”

23

“Alone?”

“My books keep me company.” And the ghosts, she thinks. Doesn’t say it. Doesn’t need to.

“Ah. Those old friends. You should get a cat. Helps keep you warm.” That it would. Better than paying for heat that dissipates before it properly arrives.

“Wood-burning stoves help too, you know. Chopping your own wood means you get warm twice.”

Percy nods to herself, watching the waves eat away at the shoreline.

“Soon you’ll be eroded away, too. Not by the waves– other things. Dreams. Nostalgia. This place swallows you whole and wears you down from the inside out, but you’ll never leave it. Not after you’ve been here for so long. It’s part of you now.” She leans close, eyes boring into Percy. Sea glass, pebbles, dull-dull-dull.

“I uh,” Percy jolts up. “I have to go. To water my cat.”

“I thought you didn’t have a cat.”

All she sees are looming eyes, swallowing up the periphery as they drown everything out. Percy thinks she’s drowning, deep in her anguish, in a forgotten old house in a forgotten old town, rickety and clam-shackled to the cliffs, the sea slowly eating its way through the rocks below her until it caves in and she falls, falls, falls.

“Yes well,” Percy’s pulling up her hood now, looking anywhere but those vacant eyes. “I lied. People do that sometimes. Anyway, have a good life. Or day? Have a good day and a good life, I suppose. Bye!”

She trots up the path, trying to keep up some resemblance of normalcy as her thoughts gnaw at her from the inside out. What was that?

She gets home, puts the kettle on. Thinks about anything but that old woman who could see more than she should. Her book, normally intriguing, couldn’t snare her in. Thoughts kept wriggling their way into her head and snagging her back to reality, where she is curled under two blankets on a threadbare chesterfield. The smoke, usually so evocative of cosy evenings, feels stifling. Everything does.

Percy tugs at the wool blankets, patched over from the moth infestation two winters before. She pulls them over her head and goes to sleep, grateful for the escape.

#

Some days the grief is so heavy, Percy blinks awake, is greeted by the rain tracing lace against the windows, and pulls the blankets tighter as she rolls back into sleep.

#

The wind is especially cutting the next morning as Percy makes her way down to the supermarket at the corner for her weekly shop. The building is old, hewn out of the same rock that makes up the cliffs it overlooks. It gives the impression of the entire town being slowly consumed by the sea, the

24

rock, the slick moss.

The neon-bright packaging is an assault to eyes more accustomed to the winter-bleached colours of the coastline. Percy is quick, shuffling between aisles with practised ease. Her bag is full when she comes to the counter, mouth twisting in a wry smile in lieu of a greeting.

Kearney had been working the shop longer than Percy had been alive. It’s the same array of packaged snacks, tinned soups, and packet of tea she gets every week. He punches in numbers, stuffing it all back into her bag and extending a wizened hand, gnarled with age, for the twenty quid Percy has in her pocket. The entire transaction lasts about thirty seconds without a word exchanged. Percy likes it that way.

The walk back is always annoying with the bag thump-thump-thumping against her left shin. She shifts it when her shoulder starts to ache, grumbling under her breath. She’s most of the way down the path to the house when something stops her.

“Hello there, little one.” She plonks the bag down, crouching beside it to reach under the Callaghan’s old porch. It’s sagging with the weight of years and pregnant expectation. The paint had been stripped ages before, revealing boards beaten into a weather-softened grey. An untied sack twitches. Black fur peeks out, eyes glowing in the half-dark. Percy continues coaxing. With a mewl, the kitten crawls into Percy’s arm, pinpricks of claws digging through her lumpy sweater.

“There there, little one,” she says, scratching behind its ears. It wasn’t much bigger than her own hands. “We’ll get you home.”

It isn’t until she’d unloaded her spoils, poured a dish of milk for the cat, and tucked herself beneath the quilt that she remembered the old hag’s suggestion from three days before.

“Get a cat,” Percy muttered to herself, tossing in a tea bag with a satisfying plunk. “He’ll keep you warm.” How a scrap of a thing would keep her warm, Percy had no idea. But she couldn’t leave it there to die, not under the porch where she’d have to smell its rot for years.

It curls up against her to sleep, a habit oft-repeated in the years to come. Percy exhales, stretching her legs out briefly before snatching them under the quilt again and drifting to sleep with the kitten pressed beside her.

#

Time passes, as time is wont to do. The black kitten was the first of many that kept Percy company over those empty years. Not much changes in this part of the world, after all. Percy still goes on her daily walks, though they became slower and shorter. Kearney’s grandson, who had taken over the shop some decades ago, stopped to scold her gently and often.

“Come now, Miss,” he’d say, nudging her cane where it rested against the counter. “I can walk with you. Them cliff’s wicked slippery with all that mist and everything.”

“I’m quite alright, thank you child.” Percy grabbed her cane, observing

25

absent-mindedly that this child was over a foot taller and now had a beard. When had that happened?

She wanders back home, down the winding path that had worn itself down with her own footsteps over the last half-century. Percy’s thinking about stopping at the bench, just to look at the view– she can certainly make the walk home herself– when she draws up short.

“Hello again,” she says.

Blind eyes turn to her. She hasn’t aged a day, or perhaps several centuries. Percy couldn’t tell.

“Hello. What do you have for me?” But Percy is already scrabbling through her bag. Like everything else after all these years, this conversation was well-worn.

“I’ve got some chocolate biscuits, would you like those?”

Her clawed hands reach out in eager anticipation, snatching a few away and tucking them somewhere Percy couldn’t see.

“You took my advice about the cat.”

“And the wood, though I usually ask one of the boys to help me now. My bones are too stiff these days.”

“Ah, yes. A lifetime of salt does that.”

The silence drifts like woodsmoke between them. Companionable, almost. Percy understands now.

“You understand now, I see.”

Percy nods her assent, no longer bothering to wonder if the blind woman could catch the movement.

“Well then. I suppose there’s not much left for you to learn. Just the next journey ahead of you.”

“There’s only one adventure left ahead of me at this point.” Percy quips, watching the waves throw themselves at the rocks forty feet below.

“I look forward to welcoming you home.” #

Percy’s funeral is a small one. A handful of the village turns out to ensconce her in a cedar coffin in the old churchyard. The house is left to wear away in the salt and the wind. Sometimes, though, two old women are spotted on the bench overlooking the cliff, sitting in silence and feeding the crows. If you stop and speak to them, you’d find yourself giving little bits of yourself away– just that once– until the salt-laden beating of the wind drives you home to wonder about decay, the steady plod of time, and the old house on the cliff’s edge that always has a cat on the porch.

26

Big Sur Christian Kubik Cedeño 27

28

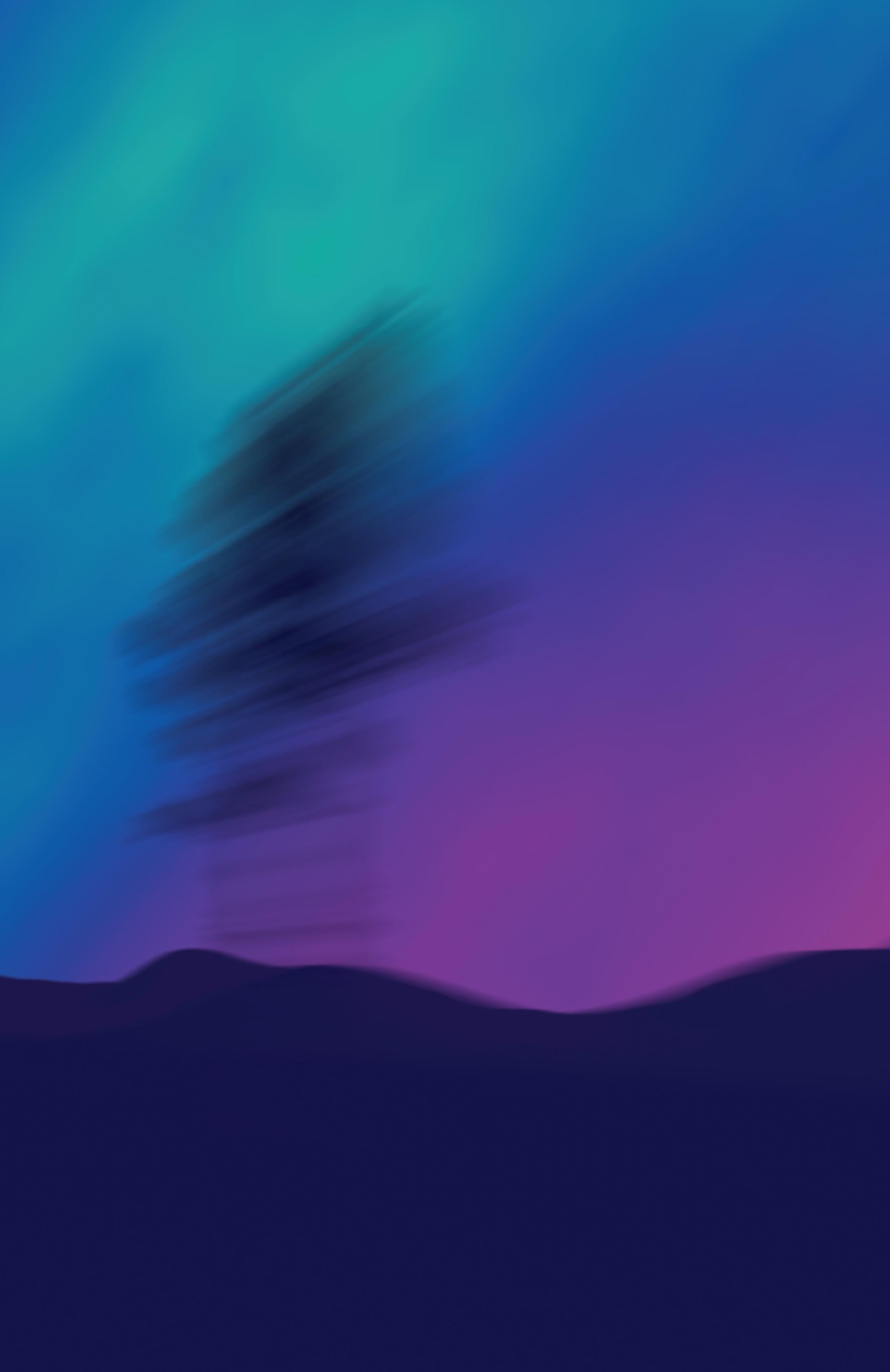

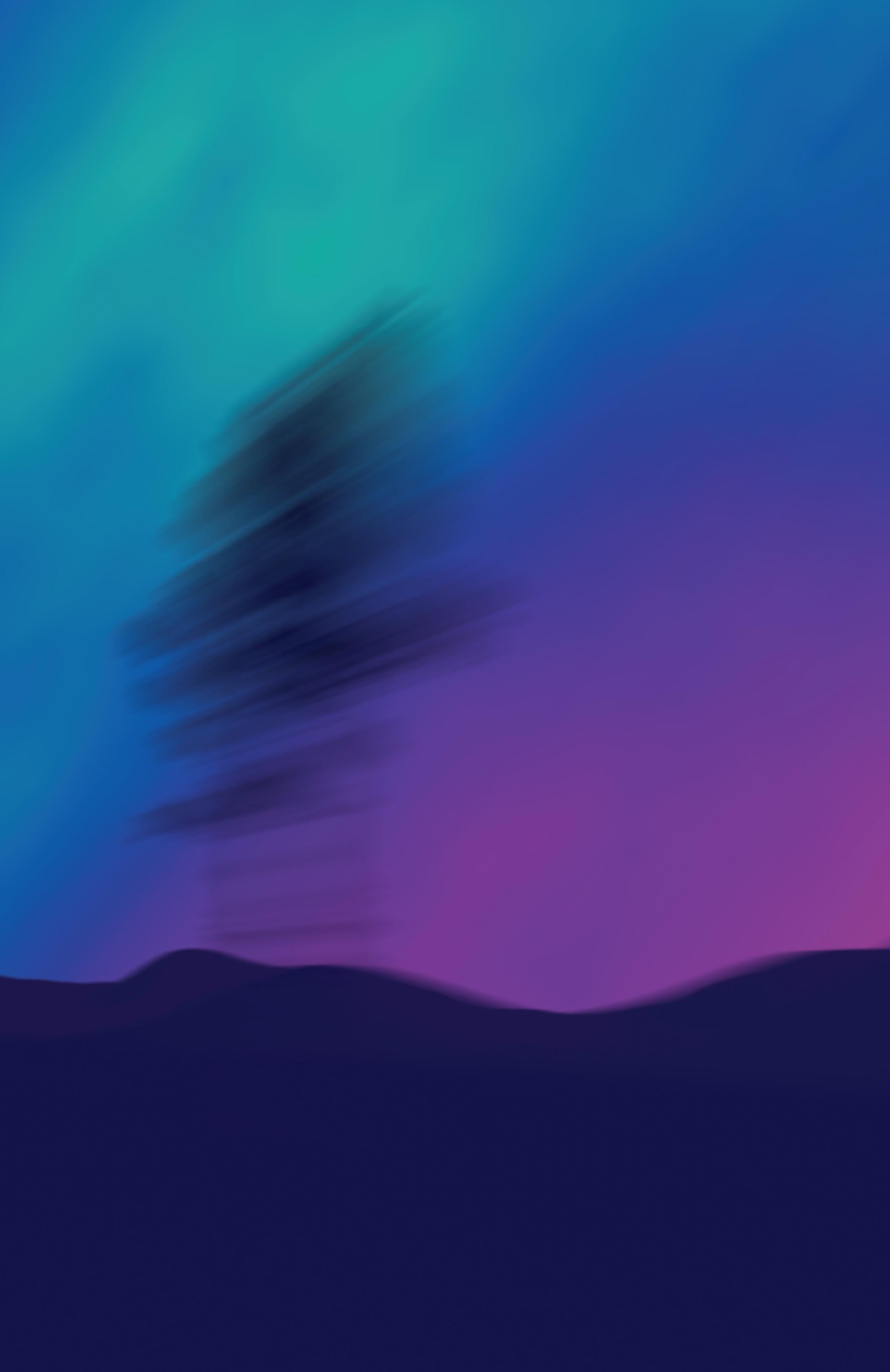

Eternal Sunset Poster Luke Rizzotto 29

Waiting

30

Arianna Pride

Island Sunrise

Lily

Finch

Morning unfolds in waves of red eyes like wet stones dread dawn as sunrise unfurls discreetly behind your back on the gray sand beach where seagulls swarm the sky and watch you swim beyond to greet the sun as I drown to remember you by

In the abstract

Little empathies wake the dead an abstract portrait of water lilies floats downstream where you once lived by the lake house, fixing holes we made to immortalize the broken hearts of leaving The lake is empty The house is drowning You realize the truth of it. In unborn embraces

Sharp blue

A sharp blue tulip unfolds at the breakfast table petals molest the fabric, and the flower is a way to escape the darkness of people around you listen to the beat in the palm of your hand, the loud wind rustles trees and the soft grass on the other side of Monday where weeks slide into days and the river murmurs your name as thunder remains the same Inside you

Running nowhere

Running. Running. I run to escape the pelting rain. It slams the sidewalk loudly and forces umbrellas to swing up quickly. I stomp the puddles and watch my reflection move to a sad place on my trousers. Hail falls from the sky, like frozen confetti. I’m transfixed under a street lamp. When I look about, you’re nowhere in sight. The sun pokes its face above the tree top canopy of leaves. We meet somewhere in the middle of seasoned trunks. A long-distance out wind sweeps up from the sea, carrying loads of bleached shells. Your thighs like white foam pitch against my solid hands. I call out when you slide through my fingers. You’re absence brutal and unyielding Running. Running. I run nowhere ahead of me, searching for you.

31

32

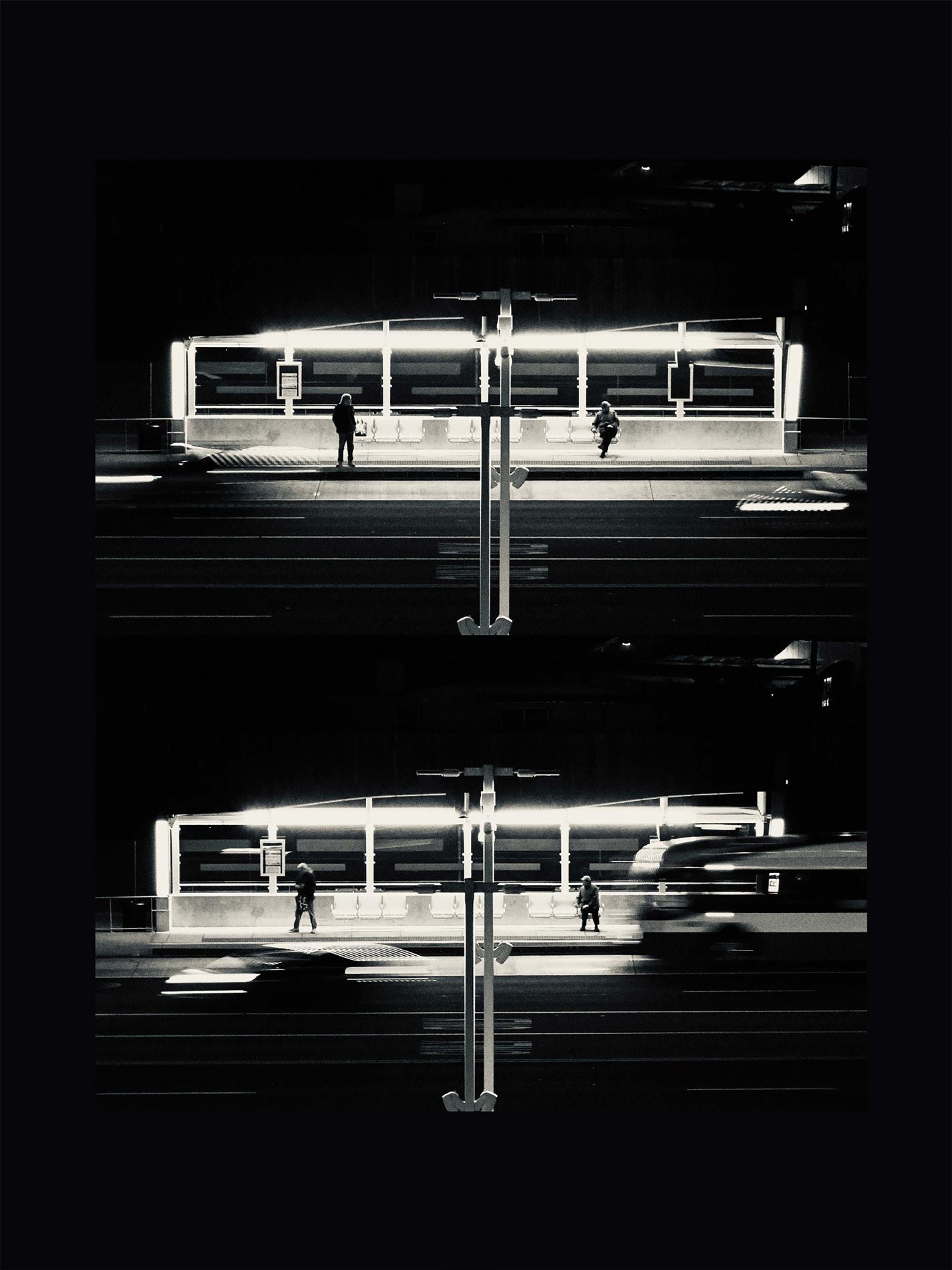

Juliette Northam On My Way

Summer at the Beach

Jordyn Becker

We held mugs of cold coffee while we sat on faded wicker rockers on a rickety porch.

We listened to seagulls, neighbors, and striking waves instead of each other.

We walked down the trail and up a steep dune, to a blue and white day that burned the soles of our feet before we set foot on the sand.

We waded in the water, scraped toes on the rocky bottom, scalded eyes with coarse salt, until we were deep enough to pretend we could start over.

33

Existence

Bharti Bansal

There is a void in my chest

The size of a country

And I am a resident

Who doesn’t know

If world beyond these cardiac walls exists

There are many birds here

That don’t sit on my veins

They run and run on their claws

As if this ground is sky

And I am floating in a river of rotting hopes

The trees swaying in my blood

Hurry when a world of my ceased dreams collide

Like a hurricane unannounced

Who knows when this country will be abolished

Who knows if I will be a sole survivor here

If I am the only oppressor and resident

What do I choose

The freedom of my heart

Or the chains of my body?s of my body?

34

The Organic Rely on the Inorganic Christine

35

Wilson

Raining Thunder

Aiden Sosa

Hear my cry. Though they may be loud and ripping, they are praise for you. The nourishing waters filling with silt are spreading all across the land to dried plants and parched rivers in this trying time to give hope to what was before to be doomed. The lights refract and bow into color, and the water comes together to present its glory in grand spectacle seven times over. The flowers perk up, and the worms and beetles bust to the surface to see the commotion, with the birds picking them off alongside the mice and the spiders. Fish come see their way of life fall into their bigger pitcher, and flop on the surface to celebrate with the mosquitos who got caught in the downpour.

This miracle is one to dance for, and my dance can even summon it. The trees' heavy arms sway and jostle in rhythm with the winds, and their roots suck up everything they can. The grass is greener and the dirt wetter, with the blood of the earth trapped in the noses of all that can smell it, and she is bleeding for all that live on it. The bloody streams give what they can to all who can take, with dirty water muddying the plains so it can survive.

Upon this hill, I gaze upon your body weeping for us, in remembrance of what once was. There used to be people here, chasing our prey across the long grass. We used to forge from blackened rock and make homes from what we caught. We used, we used, we used. There used to be many things here. There still is a lot, but it isn’t the same. Changed and used and destroyed and burned and slaughtered and raped and converted and feared and too many other things to remember. For both the victim and the victor.

Perhaps we could go back to how it was, but it is too late, isn’t it? They have taken it for themselves and never cared to learn what it was, and we couldn’t even remember ourselves after God made us forget so we could enter Its heaven. Yet here you stay, still trying to keep it how it was. Lush and green, so a spark doesn’t take it all away. Filled to the brim so the fish won’t lose their breath. Windy and cool, so the birds may soar to their greatest heights.

The bear looks at her distorted portrait in the river. The deer hears the percussion of his antlers outside of combat. The foxes jump as the thunder hits their perked ears. I sway as the wind guides my hair to its fullest volume alongside the tall grass.

36

Perhaps it was inevitable. Time moves on, and some win. And others lose. Even if I am mad, what could I do? No one controls time. Yet, here I sit. Watching as the lightning paints the sky and time passes. Perhaps this is how you do it?

Even if the bison are gone, and the lands plundered, and the sky a foreboding grey, it’s still here. The rain is coming down, and cradling all those who still need it. The lightning is illuminating the world for those who need to see. The thunder is covering the noises for those who must be hidden. Raining thunder, hear my cry.

Thank you for not abandoning us.

Respect and Protect Our Native Wetlands!

Ai Ana Richmond 37

What Might Have Been Emily Eddins

I spent months then years

Spinning the fable

Of what our life would be

I loved you through the decay

Our plans rusted our hearts banged up

We built our world on bones

The smell of blood in the soil

Old dreams made of dirt

That crumbled under pressure

The wind pushing us forward

Now regret is an undertow

And memories bring me lower Than a salamander’s belly

Disappointment is the grave

Where buried hopes lie

And echo like a lock

Blowing on a chain-link fence

High above it

A single bird in a tall tree

Calls into the night

What might have been What might have been

38

Let the Thoughts Be Juliette Northam 39

Heaven Sent Lamprey

Heaven Sent Lamprey

40

Brooke Germain

Landed

Halley Fehner

The music always blared at Hank’s, the kind of noise that obliterated any other thought. Us regulars would sit around the bar and occasionally try to talk, and we were like fish in an aquarium, opening and closing our mouths. I liked it. It helped me not think about how I’d been forced into an early retirement or how I would eventually go blind. So the cacophony suited me, until I met Jody that is.

Jody started working behind the bar about a year after I started going to Hank’s. She had long hair that she tied up in a messy bun, and did this beautiful sashay as she went up and down the bar, swinging her hips in a half dance to the beat. She was in her late forties—younger than me, but not by that much. All the regulars were in love with her. We were dying talk to her, but nobody could because the music was too loud.

And so, one evening, I pulled out a pen and scrolled my opening salvo on a cocktail napkin—Jody, it’s too loud in here. Not creative, but safe. Neutral. I didn’t want her to think I’d overthought it. I passed it to her, and she motioned for the pen.

Hank is going deaf, she wrote. He thinks it sounds fine.

Okay, but now we are all going deaf. I’d secured a whole stack of napkins, just in case this was a long conversation.

Touché.

The next night, the music was quieter. And that’s how I met my wife. #

Jody tells it differently—less about the cocktail-napkin courtship, and more about the backstory. She had worked in bars since her twenties, and had dated almost exclusively men she’d met while bartending. Strays, she called them. The kind of guys you couldn’t take home to your parents. She adopted cats with them, drove them to AA meetings, thought she could fix them. Her dreams of a family slipped away. By the time she started working at Hank’s, she told herself she was finished with men. She was a confident, strong woman, who had some cats from previous relationships, but who didn’t at her age?

“So why me?” I asked. Marrying Jody was the most unlikely thing that had ever happened to me, and I was still shocked.

“Oh you,” she said, shaking her head as if she couldn’t believe it either.

41

“You were the mangiest of strays I’d ever seen.” #

Up to that point, I’d lived most of my life in the air. After I got my pilot’s license, I opened a P.O. box in the town where my sister lived and had no permanent home. I traveled to six continents by my mid-thirties. I lived out of a roller suitcase, packed with my extra uniform, two off-duty shirts, and jeans. Life was the thrill of the runway—those moments when the plane ascended and seemed, for a moment, to defy logic. I was always going somewhere, or so it felt.

Then I started to get flashes of light in my right eye. If I was flying at night, they seemed like lightning off in the distance. I confounded my co-pilots by avoiding storms that didn’t exist.

It was macular degeneration. “How quickly?” I asked the ophthalmologist. He waved a hand. “A while, with some careful management. But your vision is already compromised. It’s my professional opinion that you no longer fly.” And so, my life seemed to start counting down. I was fifty-four, unmarried, and grounded. I found myself a permanent address and a regular bar. And then, Jody.

The problem, I found, with marrying your bartender, is that she no longer wants you at the bar. Jody said I was distracting, and she didn’t like me watching her all the time. Her tips depended on a certain level of breezy sweetness. The husband sulking at the end of bar ruined the effect. I tried other bars, but none of them fit me the way Hank’s did. The library down the street was open until 9, so I went in. If Hank’s was like Woodstock, then the library was like a cathedral—so quiet that even the smallest skid of a chair could be heard on the other side. The windows were large, smooth panes of glass, and the darkness outside clashed with the brightness inside. I had read so few of the vast number of books out there, and by God, there wasn’t that much time left. And so, I started my reading project: every night when Jody went to work, I went to the library. I started with the Classics, and sat at a long, communal table, diagonal from a teenage girl who also came every night and stayed until closing. She had long, bird-like arms, slender everywhere except for her middle. It took me awhile to realize she was pregnant. She worked on her homework—calculus, history, English—and soon we found ourselves both reading The Great Gatsby. She held up her copy, smiled, and then whispered something I couldn’t hear at all. I cupped my hand to my ear, and she spoke again, but then stopped, embarrassed.

#

42

Can you blame me for trying the same technique again? I brought out a pad, tore out a page, and scribbled a note. It is so deathly quiet in here. How do like the book?

She furrowed her brow, glanced at me, then pulled the paper close. The characters are awful. But the writing is lovely. What do you think?

I agree—Nick should find some better friends. I paused, wondering how to ask what I really wanted to know. One time, when we were both leaving at closing, I’d seen her turn down the street at the end of the block, where the only buildings were two gas stations and a women’s shelter. You come here every night, I added.

As do you.

I am slowly going blind. I’ve decided to read all the books before I do so.

She stifled a laugh. I’m sorry, that’s really not funny. Is reading bad for your eyes?

God, I never thought of that. That’s a good question. Why are you here every night?

I don’t really have any other place to go.

Her name, I found out, was Esther, and she was sixteen. Her parents kicked her out when they learned she was pregnant, and so she had stuffed a weeks-worth of clothes into a trash bag and moved across the country with her boyfriend, who was in college. He’d told her he would find them their own place, but after a couple weeks of squatting in his frat house, she realized the situation for what it was. Who wants to live with their pregnant, underage girlfriend at college? She enrolled in the local high school and checked into the women’s shelter. It was better than the frat house. Her boyfriend hadn’t come looking for her.

What will you do when the baby comes? This was a week later, after we’d talked incrementally on paper and outside, standing on the steps of the library after closing, hugging ourselves in the cold, our voices unnatural from disuse.

Esther looked at me and shook her head, her face so sad that I couldn’t stand it.

“Esther,” I said. My voice seemed to echo off the windows. I was a little hoarse. “I’d love for you to meet my wife.”

We greeted Jody at the backdoor of the bar, and as soon as she saw Esther, she flew down the steps and pulled the girl into her arms. Esther started to cry. “Oh honey,” Jody said. “You should move in with us.”

And that’s how we met our daughter.

43

#

Esther tells it differently—years later when she has moved into her own place, her daughter deep into elementary school, she will bring her future husband over to meet us, and explain to him that it wasn’t Jody who convinced her to move in with us, but me. What kind of middle-aged man writes notes to teenagers in the library? Once she’d determined I meant well, she felt that she would know me forever. “How long did that take?” I ask.

“About five minutes.”

Esther also has her own theory about why Jody chose me. It wasn’t that I was the mangiest stray around, she says. It was that I was the kind of person who would take in a couple of strays myself.

#

Esther’s daughter, Maya, was born in the deepest, coldest part of winter, and we brought her home under a pile of blankets Jody had made for her. Neither of them quite the right age for first-time motherhood, Esther and Jody embraced co-mothering. They swapped parenting books, took Maya to her doctors’ appointments together, passed her back and forth with the smallest glance. Jody took half of the night shift, scooping up Maya the moment she got home from the bar and shooing Esther off to bed. And I took care of the two mothers, doing endless loads of laundry and scraping together meals.

“Who would’ve thought,” I said, one evening as Jody sat in the rocking chair in the living room, Maya on her chest. We marveled at our new life, our favorite conversation to play on repeat. “If I’d never gotten grounded, it would’ve never turned out like this.”

“Not grounded,” said Jody, stroking the top of Maya’s head. “Landed.”

I’d gotten used to thinking of my life like I was barreling down a runway, the plane rushing at full force, about to take off. I took pride in how I traversed the globe, so small I could fly around it a thousand times in a lifetime. I’d seen a lot of the world, but really, a lot of what I’d seen looked like the beige lobby of a Marriott. My existence had been light, leaving only a trail of barely used hotel shampoo bottles and a sea of Styrofoam coffee cups. But Jody was right—maybe my real life began when I touched down. I could run out to get groceries or a book from the library, and then come home to these three women, and it was like walking out of the airport terminal into the warm sunlight. I’d been traveling so long, and now I’d arrived.

44

Memory

Memory

45

Sherry Shahan

Eden

Eden

46

Dorothy Moss

The Apple on the Tree

Diana Quintero

Seduction so sweet

That not even the purest of souls

Could detest

Deep crimson set before my eyes

In a background dressed in black and white

Gleaming and shining

With promises of a new life

But once I was finally set free

The horizon fell to its knees

Painting sunsets in a diversity of hues, Humanity, too

I knew that once my finger touched And grasped the pearly surface There would only be before And all the immoral that came after

Ridding the world of its absolutes I allowed liberation from the roots

Deforesting the past In creating a new tale

And with a hissing behind my ear

Temptation set us free

At a small cost

Of what I would be.

47

The Silence of Wild Things

Ned Weidner

The snow fell softly on the granite boulders and pinyon pines around us muffling the sound of the horses’ hooves as they touched the earth. The squirrels and chipmunks which had been busily stockpiling for the months ahead were nowhere to be seen. The jays were silent. The rustle of the Aspens quaking in the wind and creek running hundreds of feet below, the only sounds minus our heartbeats and breathe. They had to be close, the six missing cattle. I was helping my neighbor Larry round up some of his cattle for a fall branding. We figured they were laid up in some cover getting protection from the wind.

Larry flipped the collar on his jacket and tucked his bare neck deeper into it. I pulled the brim of my hat lower. It wasn’t winter, but winter wasn’t far off. He pointed to large tracks in the dusting of snow. Four toe pads, a round paw pad and no claw marks. There was only one thing capable of making tracks that big. Larry reached down and brushed his 30.30 tucked in the saddle holster. We rode on and rounded a bend on the ridge. We had to be back soon, or the rest of the branding party would come looking for us.

As we turned the corner, we noticed an animal, pale and brown moving parallel to us on the ridge across the creek. Larry glanced down at his holster. In the valley below us we could make out the black outlines of four cows lounging in the shelter of the manzanita.

We rode down to them keeping a watchful eye on the body moving across the adjacent ridge, until we could no longer see it. When we reached them, a heifer and two cows with calves, they bellowed and mooed, clearly not wanting to awaken from their seeming oasis in the wintery brush. I slapped my chaps and yelled “Hey cow! Come on cow!” to rustle them up.

No sooner did I slap my chaps a third time but a flash of yellow and brown jumped from the brush and grabbed the smallest calf by the neck. Larry swung his rifle and aimed to shoot. The cougar froze and looked back at Larry – eyes wide and hungry.

The calf, neck broken, flopped lifelessly in his jaws.

Larry didn’t pull the trigger.

I watched him hold his 30.30 firm against his shoulder. He breathed steady.

48

His eyes didn’t flinch. Neither did the cat’s. I grabbed my own rifle and pointed it at the cat. Neither Larry nor the lion moved.

And then as quick as it had jumped into the scene, the cougar jumped back into the brush and disappeared with the calf in its jaw. I looked at Larry. He looked at me. “Let’s get the rest of these cattle back home,” he said as he tucked his rifle back in the holster. I didn’t say a word. It was his herd. Instead, I moved behind the three cows and pushed them forward to the trail.

We rode in silence for miles on the way back. The muffled sound of horse hooves, beating hearts, and the lonesome bellows from the cow whose calf had been taken the only sounds until we approached the top of the hill and looked down on the fire of the branding party and heard laughter and music bouncing off the valley floor. Larry looked at me, his collar flipped and hat brim pulled low. “It is the way of the wild, my friend. We all have to eat.” And we rode down to join the branding party’s fire.

49

Our Lady Amuri Morris

50

Our Town Sherry Shahan

51

Thank you for reading the first volume of Brushfire’s 76th edition. Our team hopes the poetry, prose, and artwork collected within these pages made you laugh, cry, and—most of all—think. It’s a big hectic world out there, but great art can bring us all a little closer together.

To all of our submitters: we greatly appreciate your creativity, dedication, love for the arts, and freedom of expression. You are what makes Brushfire unique.

Again, thank you for your enjoyment of the University of Nevada, Reno’s literature and arts. We’ve brought the Brushfire to you for 76 years and the fire continues blazing thanks to passionate readers like you.

With your support, many more editions of Brushfire await. We couldn’t be more excited.

My Hero

My Hero

53

Ana Cruz

Executive Editor

Arts Director

Visual

SPRING 2024 BRUSHFIRE STAFF

The Publication Currently Employs 6 Part-Time Student Workers. Meet the Small Dream Team Below!

Danian Arguello

Literary Editor Paige

Literary Editor Cheyenne McGregor

Staff Writer

Madison Kitch

Audiobook

Abigail MacDiarmid

Krueger

Producer Israel Cruz

Abigail MacDiarmid

Krueger

Producer Israel Cruz

54

Meet You Under the Stars Jason Mennel 55

Interested in volunteering, upcoming gallery exhibitions, poetry nights, or other literature-and-arts-related events at the University of Nevada, Reno?

Want to check out e-book or audiobook versions of all your favorite Brushfire editions?

Visit our website: unrbrushfire.org

Never miss out on the latest Brushfire events and posts! Follow the University of Nevada, Reno’s Literature and Arts Journal on Instagram:

@nevadabrushfire

BE PUBLISHED IN OUR NEXT EDITION

Yearly, Brushfire publishes a spring and fall volume. We accept poetry, prose, and all printable forms of art from everyone, everywhere.

56

Indulge

Indulge

Spring Barn

Spring Barn

Heaven Sent Lamprey

Heaven Sent Lamprey

Memory

Memory

Eden

Eden

My Hero

My Hero

Abigail MacDiarmid

Krueger

Producer Israel Cruz

Abigail MacDiarmid

Krueger

Producer Israel Cruz