23 minute read

Historic Context

from BOARD & BATTEN THE LEGACY OF KIRKBRIDE AND THE THERAPEUTIC LANDSCAPE

by University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning, University at Buffalo

Figure 4-1: Muth of the Erie Canal in Buffalo, NY

Source: Keystone View Company

Advertisement

Figure 4-2: 1901 Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, NY

Source: United States Library of Congress

Overview

Introduction to Buffalo NY: The nineteenth century The City of Buffalo, NY was established in 1832, but had already been growing for some time at that point. 1 The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, connected Buffalo to Albany for the first time, and became a gateway for the Atlantic Trade to the west. 2 In 1842, the first steam-powered grain elevator in Buffalo was developed, and with this, unlimited access to grain at the Port of Buffalo, leading to an industrial and economic boom lasting into the 20th Century. 3

By 1860, Buffalo had become the tenth largest city in the country with over 80,000 residents, and growing rapidly. With the country’s eyes on Buffalo, the likes of the nation’s most profound city planners, designers, and architects found themselves commissioned on planning projects in the city. 4

Well known landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted left a significant impact on the City of Buffalo, designing an extensive park system of six different parks throughout the city, each of them connected by a series of parkways. He also described Buffalo as being “one of the best planned cities in the United States, if not the world.” 5

The 1901 Pan-American Exposition was held in Buffalo from May 1st to November 2nd. Buffalo, in 1901 was the eighth largest city in the United States, with a population of 350,000 residents, and well-connected railways, and because of this, was chosen to host the 342-acre Exposition. The Exposition showcased the latest advancements in electricity, notably hydroelectric power, which was generated in nearby Niagara Falls, and hosted the top engine manufacturers. The Exposition also provided visitors with entertainment, called the Midway, where exhibits included attractions like the “House Upside Down.” The Exposition is perhaps most famously known for the place where President McKinley was shot on September 6, dying later of an infection from his wounds. This happened just to the

Mental Health in the United States

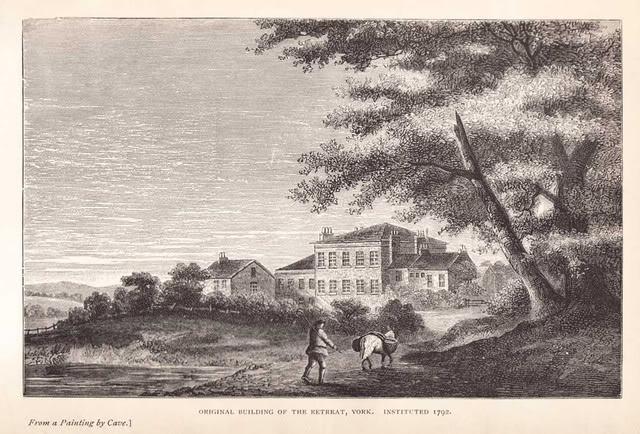

During the 18 th century, new ideologies on the treatment of the mentally ill became popular, and increased numbers of hospitals were commissioned. As the number of individuals with mental illnesses began to increase around the world, there needed to be a place where they could go to be “cured” of their aliments. Europe saw some of the first hospitals for the mentally ill. These hospitals were created based on the “moral theory” of treatment. A famous example is York Retreat in England. 6 This model included a location in a pastoral setting with a central administrative structure and wards with double loaded corridors. Being in a pastoral setting, there was the opportunity create a small community that was the hospital. Patients at York Retreat were treated using a daily routine of rest and work, along with outdoor experiences and connecting to nature. 7 This asylum was used in a curative way and did not use any harsh experimental treatments on the patients. The asylum was not meant to be punitive to the patients, it was instead made to help them heal. The United States took many ideas from European models for the treatment of the mentally ill. The moral treatment theory and its relation to hospital architecture shaped many of the hospitals for the mentally ill that were created through the second half of the 19 th century. There was a significant increase in the mentally ill population in the United States, and there was a need for institutions to house these patients. There were over 150 state insane asylums built in the 1800s in the United States. 8 The maximum capacity for these new institutions was raised from 250 patients from 600 patients. 9 There also was an increase in medical professionals to treat the growing number of patients. The hospitals at the time followed the Kirkbride plan, characterized by a central administrative tower and wings of wards spanning out from

Figure 4-3:

The York Retreat

Source: Gemälde von Carve

Figure 4-4: Image depicting the layout of the Kirkbride Plan

Source: Goody Clancy

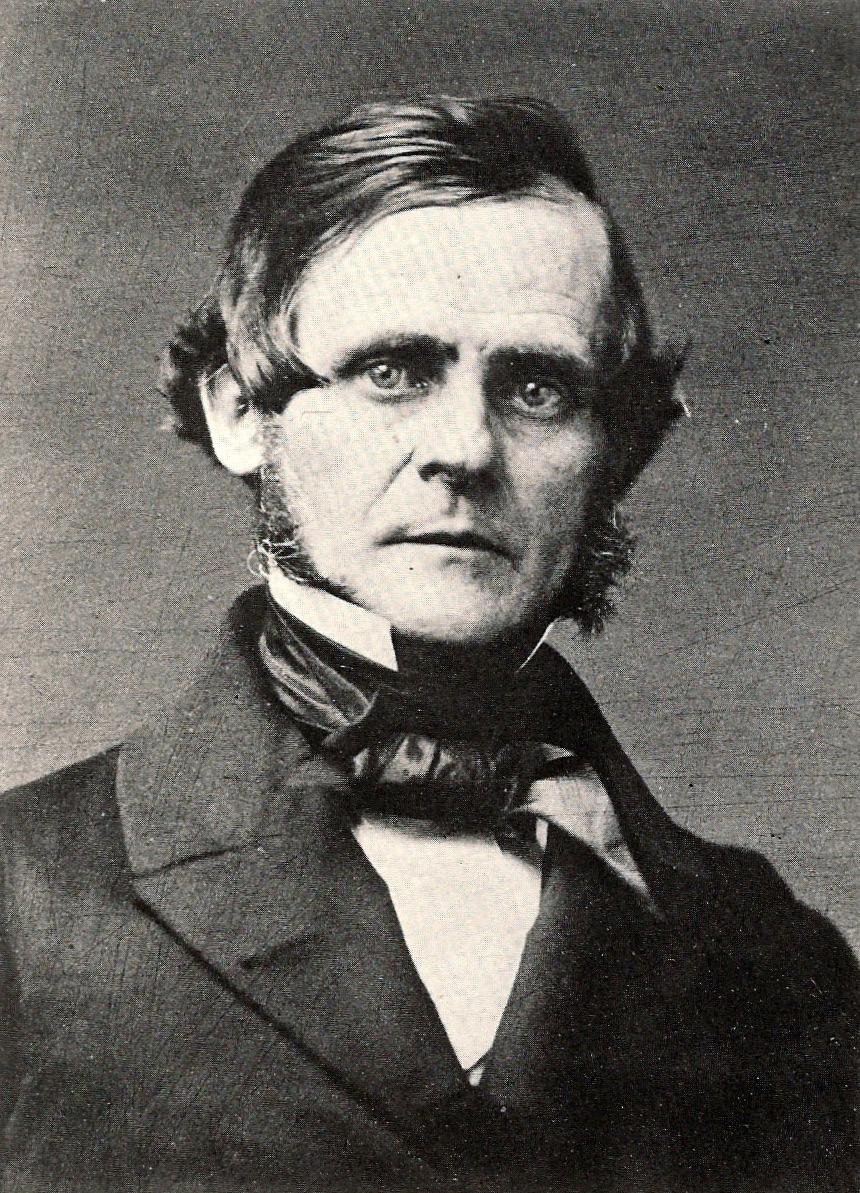

Figure 4-5: Kirkbride

Dr. Thomas Story

Source: Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital

Gallery

Figure 4-6: Insane

Friends Asylum for the

Source: Historical Society of Pennsylvania the center. 10 The hospitals reflected the ideals practiced in Europe and new adaptations to fit the newly constructed hospitals. The design of the buildings was imperative into providing treatment for the patients. As time went on, the traditional Kirkbride plan was modified into the cottage plan, where wards became increasingly more separated and became communities within themselves. 11 Patients worked, experienced the environment around them, and followed a strict routine to help cure their ailments.

Dr. Thomas Kirkbride

Thomas Story Kirkbride was born in Bucks County Pennsylvania, in 1809, on a one-hundred-and-fifty-acre farm, who descended from a very old and distinguished Quaker family. At an early age, he and his father decided that he would not take over the family farm, but rather, the young Kirkbride to go into medicine. In preparation for a medical career, Kirkbride’s father provided him with an expensive secondary education – an education few were privileged to receive. During the early to mid-1800s, entry into the medical field required no formal schooling. Most doctors possessed only a common school education, and even fewer, a college degree. Even prior to his medical degree, Kirkbride was amongst the best-educated doctors of his day. 12

After his secondary education, Kirkbride began his medical training with an apprenticeship to a physician in private practice where he learned the basics of traditional medicine. It was common for aspiring doctors to apprentice themselves to a practicing physician, which was sufficient to earn a medical license, prior to entering medical school. Kirkbride entered the prestigious medical school at the University of Pennsylvania in 1828 where he learned a more sophisticated intellectual framework for understanding diseases and its treatment; however, he learned very little about the nature of mental diseases and their treatment

1832, and not getting his first choice of residency at the Pennsylvania State Hospital in general medicine, he accepted a residency at the Friend’s Asylum, outside of Philadelphia, where he gained his first practical experience with the treatment of the mentally ill, which was based on the European system of moral treatment. 14 After learning the basics of asylum care of active treatment at Friend’s Asylum, he left in 1833, when he was admitted to the residency of his liking in general medicine at Philadelphia. 15 The basics that he learned as an apprentice of traditional medicine – that is, diagnosis, therapeutics, and regimen, in addition to his good-natured, country boy, Quaker values, he attained as result of his agrarian upbringing of hard work, pragmatism, and moderation – would go on to help shape his life’s work in designing the conception of asylum treatment. 16

In 1841 the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane opened two miles outside Philadelphia, located on one hundred acres, specially designed to provide intense, regimented treatment for the mentally ill. 17 Kirkbride, being chief physician at the time, had complete control over every aspect of its operation, and followed well known European precedents that reflected the idea of moral treatment based upon minimal physical correction, incentives to self-control, and firm paternal direction. 18 In other words, if treated like rational beings, the mentally ill would behave like rational beings. 19 Kirkbride presided over the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane until his death in 1883, and during his tenure, it was considered one of the finest insane asylums in the United States, laying the groundwork for the Kirkbride Plan. 20

The Kirkbride Plan was the preeminent design for insane asylum’s in the United States from 1841 to 1880. 21

The general layout of the 1854 Kirkbride plan consisted of two major components: the interior environment of lighting and ventilation, and the classification of patients. The wings radiated off the central building, in a staggered pattern, so that each ward, with

Figure 4-7: building

Interior of a Kirkbride Plan

Source: Peabody Institute Library of Danvers

Figure 4-8: New York State Lunatic Asylum in Utica, NY

Source: “History of Oneida County, New York”,

by Durant

no less than eight in each wing, had good ventilation, its own staircase, and views of the grounds while allowing for maximum separation of the wards. At the end of long halls, the wings had bay windows to allow light and air to enter. The worst patients were in ground-floor ward farthest from the center building and best in top-floors, closest to the center. The interior had to maintain the cheerfulness

of its grounds, landscaped gardens, fountains, and summer houses, designed to hide the custodial appearance of the insane asylum. The carefully landscaped exterior grounds contributed to the healing of patients as much as the interior spaces because it was thought that one’s own environment contributed to one’s mental health. 22

Because of the work of Kirkbride, the idea of landscape gardening as a restorative measure to one’s mental health, was evolving. Andrew Jackson Downing, a proponent of rural landscapes, was at the forefront of this movement with his design of therapeutic landscapes first incorporated into hospital grounds at the New York State Asylum in Utica, New York, in 1842. This rural, or pastoral landscape, consisted of open lawns, water features, trees, curvilinear walks, carriage drives near the center of the buildings, and panoramic overlooks. This informal pastoral landscape was asymmetric, curvilinear, and naturalistic, rather than formal and geometric, which was soothing to the viewer. Downing’s views in naturalistic landscape gardening influenced the later works of landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmstead. 23

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted was born in 1822 in Hartford, Connecticut. 24 His father, who was a great influence in his life, often took Frederick on horseback throughout the countryside around Hartford, before he was old enough to sit on a horse, to admire the scenery. 25 These short rides turned into annual tours that took Olmsted through the Connecticut Valley, White Mountains, up the Hudson River, west to the Adirondacks, lake George, and finally to Niagara

Falls. 26 Reflecting on his youth, it was not what he studied that he best remembered, but what he did. 27 As a child, Olmsted’s countryside wandering was encouraged and most the time he was busy helping on neighbors farms, and happy outdoors. 28 The earliest lessons in aesthetics came from the American landscape that Olmsted experienced in his youth. Late in his career he said, “The root of all my good work is an early respect for, regard and enjoyment of scenery…” 29

Olmsted participated in the design of five asylum landscapes and believed that the workings of the sane mind were not so different that the insane. 30 The pastoral landscape at the Buffalo State Hospital that Olmsted designed was incorporated into the therapeutic program that the hospital offered to the patient’s mental health and healing. Olmsted’s pastoral design was soothing, informal, asymmetrical and naturalistic rather than formal and geometric. Consistent with this design and the Buffalo State Hospital was open view across the landscape, gentle topography, round headed trees, broad lawns, reflected water surfaces, curving drives and walks, and broad patterns of sunlight shaded by deciduous trees. 31 The effect of this landscape came in such a way that the viewer was unaware of its workings, designed to affect the viewer, with the absence of distractions and demands of the conscious mind. 32

Figure 4-9:

The ponds originally located next to Elmwood Avenue

Source: Cultural Landscape Report

Frederick Law Olmsted did not consider landscape architecture for his profession until later in his life, at age 43 to be precise. 33 It all started in 1857 when he secured the position of Superintendent of Central Park in New York City. 34 As superintendent, Olmsted was director of labor and police, and would be responsible for enforcing the rules related to public use of the park. 35 The following year, he and his partner, Calvert Vaux, a trained architect whom he was acquainted with, won the design competition for Central Park. 36 They explained in their winning plan, dictated by nature and the popularity of the English school of landscape design, that their intention was to create

contrasting scenery to suggest to the imagination a great range of rural conditions. 37 Within two years of starting the work on Central Park, Olmsted and Vaux had a growing architectural landscape practice. 38 Olmsted considered his responsibility for the park’s artistic success equal to that of Vaux, but regarded himself as a better manager and organizer of the work, as he was architect-in-chief and in charge of construction from 1859 to 1861. 39 However, when Vaux and Olmsted were working on Central Park, the term “landscape architecture” was not yet in use, and the practice itself, as a profession, was in its infancy. 40

There were very few practicing landscape gardeners when Olmsted and Vaux won the Central Park competition. Andrew Jackson Downing was perhaps, one of the most influential early pioneers of what would become known as landscape architecture, in modern terms. A native of Newburg, New York, Downing accepted a partnership with his older brother in the nursery business in 1831, and spending his spare time roaming the countryside admiring scenic landscapes. 41 Downing published, to great success, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening in 1841, which laid out his ideas, that were based on his travels, experiences, and views. 42

At the dawn of industrialization, at a time when cities were beginning to see larger urban centers, Downing believed that cultivators should not be underestimated, because it was not solely for the wealth, which they produced, but the moral virtues associated with agriculture that should be valued. 43 Horticulture, Downing believed, “more than any other art, brought men into daily contact with nature, giving simple, pure pleasure…” 44 Downing contributed to the idea that people surrounded by rapid industrialization of the time, prefer, and need to see, or be emerged in scenic rural landscapes for relaxation – that the pressure of capitalism caused mental stress. He promoted the idea of a simplistic rural life. Downing incorporated his ideas into the design of the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum grounds in 1848. 45 The basis for Olmsted’s ideas came from experiences of his youth and earlier practitioners like Downing. 46

Figure 4-10: Map published in 1872 showing the original site plan for the Richardson Olmsted Complex and how much larger in scale it was at its completion. Another point of interest is the lack of owned property directly surrounding the site.

Buffalo State Hospital In 1870, the Buffalo State Hospital for the Insane was commissioned in Buffalo’s 11th Ward, and brought in Henry Hobson Richardson to design the campus, along with Frederick Law Olmsted to design the grounds. The hospital opened in 1880. Designed in what is now known as the Richardson-Romanesque style, and was based on the Kirkbride Plan. Kirkbride’s ideas for the regimental treatment of the insane and Olmsted’s ideas for effects of a rural landscape on the unconscious mind of both the sane, and insane, converged to help heal patients at the Buffalo State Hospital. Asylum reformers and park enthusiasts believed that environmental factors could shape human behavior, nature was curative, exercise therapeutic, and that cities psychologically draining. 47 Kirkbride based his model on his European predecessors, and further refined the system according to his experiences as a well-trained doctor, as well as influences from his childhood that shaped his character. Olmsted, too, refined the movement of landscape gardening that was already established, based on the influences of his childhood, where he learned the value and the beauty in rural scenery, and further specialized the profession. They both were merely fuel to the fire – not spark that lit the fire.

Figure 4-11:

Buffalo State Hospital

Source: Richardson Olmsted Corporation

1870-1890 Historical maps show the area to be largely agricultural in use prior to the development of the hospital. The data shows that in the immediate surrounding area, there were only 21 properties owned from 1870-1880. The majority of the owned land was owned by Buffalo Iron and Nail and DW Clinton for manufacturing uses for the most part.34 Adjusted for inflation, the assessment values of the properties averaged only $13,000 which shows how the area was not yet an attractive area for purchasing land. From 1880-1890 however, we can see a substantial uptick in both property ownership as well as assessed property value. The key property which now shows up on the assessment rolls is State Insane Asylum. DW Clinton and Buffalo Iron and Nail both still own a considerable amount of property in the area, but there is now a high volume of property ownership by other people. The amount of owned property increased from 21 properties in 1870 to 45 and the adjusted for inflation assessed property value more than doubled to $36,000. It is clear that the neighborhood began blooming as the hospital opened. Many would argue that the park system is one of the biggest attractors. Frederick Law Olmsted was implementing his parks system in Buffalo and they would be extended to this neighborhood via the new hospital.

1910-1930: Up into the late 19thcentury, the neighborhood surrounding the hospital has shown steady and promising growth, which is a sign of a growing city. However, from 1910-1930, the area saw unprecedented growth. Both property ownership and property values grew considerably again as they did in the previous decades. In this span of years, property ownership shifted from a few players owning the majority of the 45 properties, to a large volume of different Buffalonians owning their own piece of the 90 registered properties in 1910. The adjusted for inflation property assessments over doubled again; the average hovering over $73,000. The uptick in property purchases is likely due to the Pan American Exposition that took place in Buffalo in 1901. The Expo highlighted Olmsted’s parks system and made property near the parks much more attractive. Given the hospital is now part of the system, it would only be natural that property values would spike near it.

1950-1970: This period coming after the sudden boom of the early 20thcentury was followed by the Great Depression, an economic collapse that affected the entire nation. Buffalo was hit especially hard. Buffalo had long been a thriving manufacturing city but due to the sudden economic collapse, the Buffalo economy was struck by businesses and manufacturers closing their doors. This in turn caused property values in the city to drop, including the neighborhood surrounding the hospital.

Property values dropped considerably from their height of $120,000 down to $42,000 after being adjusted for inflation.3 It is also important to note that during this time, the hospital was in a state of decline and dilapidation until its eventual closing in the 1970’s. From a close lens, the hospital and neighborhood’s declines are connected, but one could argue that they are both on trend with the City of Buffalo. It is well known that the city faced a substantial decline in the mid-20thcentury and it would make sense for older properties and neighborhoods to experience some form of decline.

1970-Present: It has been well documented that Buffalo in the 20thcentury faced both population as well as economic decline. However, the neighborhood surrounding the Richardson Olmsted Complex saw a different trend starting in 1970. From 1970-1990, property values adjusted for inflation increased from $42,000 to $65,0003though the hospital had already been closed for decades and a large portion of it being now owned by Buffalo State. If you compare the 1990’s values with the values in 2014, you can see another significant increase, signifying a neighborhood again on the rise.3 To a Buffalonian, this is not a surprising statistic in that Elmwood Ave and the surrounding neighborhoods has become a very popular area. It is not surprising to see consistently rising property values in an improving area.

Conclusion

The neighborhood surrounding the Richardson Olmsted Complex was one of much turbulence from 1870-2014. There was slow but steady improvement followed by skyrocketing home values into the late 1920’s. The question whether these changes are caused by the creation of the Richardson Olmsted Complex still remains. This is because the landscape designed by Frederick Law Olmsted made the neighborhood more attractive, being highlighted by the Pan American Exposition. However, the city faced a well-documented decline in the following years as well as the Richardson Olmsted Complex.

Figure 4-12: Brick damage and temporary repairs on building 40

Source: Siera Rogers

Figure 4-13: Roof Damage on Building 38 that needs repairs

Source: Siera Rogers

Figure 4-14: Image of original window and framing in Building 40 that will need to be preserved and restored

Secretary of the Interior’s Guidelines

The Secretary of the Interior’s Guidelines say that in rehabilitation “historic building materials and characterdefining features are protected and maintained as they are in the treatment Preservation. However, greater latitude is given in the Standards for Rehabilitation and Guidelines for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings to replace extensively deteriorated, damaged, or missing features using either the same material or compatible substitute materials. Of the four treatments, only Rehabilitation allows alterations and the construction of a new addition, if necessary, for a continuing or new use for the historic building.” The main guidelines are to identify, retain and preserve historic materials and features; protect and maintain historic materials and features; repair historic materials and features; replace deteriorated historic materials and features; design for the replacement of missing historic features; alterations; code required work; accessibility and life safety; resilience to natural hazards; sustainability; and new exterior additions and related new construction. Preserving the masonry of the buildings is important to retaining their historic character. To protect the masonry, existing historic drainage features should be intact and functioning properly. Cleaning should be done with soft bristle brushes or a low-pressure hose and detergent. Repointing deteriorated mortar joints may be necessary. Replacement in kind of any masonry that is too damaged to repair is allowed by using physical evidence to recreate the damaged element. Retaining the existing roofs, their structural and decorative elements is vital to retaining the historic character of the buildings. The form of the roof is significant, as are the roofing materials. Downspouts and gutters should be cleaned to ensure proper drainage so damage to the roof does not

occur. Roof repairs may be done if the original or compatible non-historic roof is sound and waterproof. Replacement in kind of a roof that is too damaged to repair is allowed by using physical evidence to recreate the damaged element. Original historic windows should be maintained and retained because they are elements that are vital to the buildings historic character. Repairing damaged window frames, including replacing materials with in-kind materials, is allowed. A window that is too damaged to repair may be replaced by using physical evidence to determine what was original. Original porches and entrances should be retained and preserved because their functional and decorative features are important to the overall character of the building. The original materials are also significant. Any entrances that will no longer be used still need to be preserved in order to keep the character of the building. Existing porches and entrances should be repaired and removed and any porches and entrances that are too damaged to be repaired should be replaced in kind. Interior spaces, features and finishes are important in defining the historic character of a building. Significant special characteristics including corridor size are important to retain. Protecting and maintaining interior elements such as plaster, wood and masonry are necessary. Any extremely damaged material may be replaced in kind or with another compatible material. The features of the site the building is on should be maintained and preserve. These features include fences, circulation systems, vegetation and landforms. The land should be surveyed and documented before any terrain alterations will be done. Repairs should be made to any features that have been damaged, deteriorated or have missing components. In kind replacement of any feature or element that is too damaged to be repaired is allowed.

Figure 4-15: Original porch on the west side of Building 38. The temporary boards that are in place should be removed in order to keep the character of the building

Source: Siera Rogers

Figure 4-16: This fireplace in Building 40 is a character defining feature

Source: Siera Rogers

Figure 4-17: Features on the site such as the foundation remains of the greenhouse should be maintained and preserved

Endnotes 1 The Buffalo Evening News, A History of the City of Buffalo Its Men and Institutions, (Buffalo: The Buffalo Evening News, 1908) 2 http://digital.lib.buffalo.edu/collection/LIB005/ (accessed 20 November 2019) 3 (Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor 2019) 4 (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1995) 5 Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy, “Our History: Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy - His Legacy. Our Inheritance.,” Buffalo Olmsted Parks, accessed December 5, 2019, https://www.bfloparks. org/history/) 6 Historic Structures Report the Richardson Olmsted Complex. Goody Clancy for the Richardson Center Corporation. July 2008. Page 19. 7 Historic Structures Report the Richardson Olmsted Complex. Goody Clancy for the Richardson Center Corporation. July 2008. Page 19. 8 Historic Structures Report the Richardson Olmsted Complex. Goody Clancy for the Richardson Center Corporation. July 2008. Page 24. 9 Historic Structures Report the Richardson Olmsted Complex. Goody Clancy for the Richardson Center Corporation. July 2008. Page 23. 10 Historic Structures Report the Richardson Olmsted Complex. Goody Clancy for the Richardson Center Corporation. July 2008. Page 22. 11 Yanni, Carla. The Architecture of madness: Insane Asylums in the United States. University of Minnesota Press. 2007. 12 Ibid, 45-53 13 Tomes, 57, 60. 14 Ibid., 60. 15 Ibid., 65-66. 16 Ibid, 45-53. 17 Ibid., 37. 18 Ibid., 20-22. 19 Ibid., 5. 20 Ibid., 41. 21 Ibid. 22 Ibid., 141, 142. 23 CLR 6,8,9. 24 Tatum, 1. 25 Beverage, http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles/ olmsted-his-essential-theory 26 Beverage, http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles/ olmsted-his-essential-theory 27 Tatum, 9. 28 Ibid, 9. 29 Beverage, http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles/ olmsted-his-essential-theory 30 Yanni, 9. 31 Patricia O’Donnell, Carrie Mardorf, Sarah Cody, Cultural Landscape Report (Heritage Landscapes: 2008), Part II, 9. 32 Yanni, 9. 33 http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/frederick-law-olmsted-sr 34 http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/frederick-law-olmsted-sr 35 Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), 124. 36 Ibid., 124. 37 Ibid., 137. 38 George Tatum, Andrew Jackson Downing: Arbiter of American Taste, 1815-1852 (Princeton University, 1950), 144. 39 Ibid, 145. 40 Roper, 143. 41 Tatum, 40. 42 Roper, 143. 43 Tatum, 33. 44 Ibid., 35. 45 Yanni, 58. 46 Charles E. Beveridge, http://www.olmsted. org/the-olmsted-legacy/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles/olmsted-his-essential-theory 47 Ibid., 59.